Closing the Loop

It has been almost a year since Leah Sylva joined the Digital Collections Unit (DCU) at The Bancroft Library as the Digital Collections and Metadata Librarian. In that time, she has provided crucial technical services support, moving the program forward by building on its past successes. With Christina Velazquez Fidler at its head, the DCU has largely focused on how to “close the loop” in regards to descriptions of digital materials. This process of “closing the loop” refers to an integration of the data points created at various stages of representing the archival material in our care. In the Bancroft context, this translates to ensuring that digitized materials are represented in the records of their originating collections whenever possible.

Underscoring this issue is the iterative nature of archival description, especially in the digital context. As we work with digital materials, we hold in mind the goals of maintaining archival context and improving access and discovery. These goals can only be accomplished by strategic decision-making to guide processes of observation, evaluation, and action. This often requires returning to past projects to ensure that they are meeting current standards and needs of library users. One example of this is the DCU’s newly completed The Bancroft Library Archived Websites LibGuide which preserves and provides context to past digital projects that are no longer hosted on the Library website.

As archival material passes through discrete stages of arrangement and description, new data points are created:

- Archival material is acquired and accessioned → creation of catalog record

- Archival material is arranged and described → creation of finding aid

- Archival material is digitized -> creation of digital object and Digital Collections record

Since these processes can be completed years apart, there are often overlapping fragments of metadata existing in different platforms without reference to one another. With limited resources and staff capacity, we are always making choices about what to prioritize and what to leave for another day, creating backlogs and technical debt that future generations must repay with effort and creative problem solving. With migrations between systems, changing accessibility standards, and shifts in the direction of our work, we understand that the digital landscape is ephemeral and in need of attention, maintenance, and augmentation. Digital projects offer new pathways for access and discovery alongside significant technical challenges that must be resolved as part of a process of quality control.

“Closing the Loop” case study: Moving Images from Environmental Movements in the West, 1920-2000

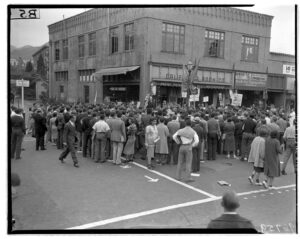

These recordings, comprising 130 videos from 8 distinct collections, were digitized under a Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) grant to preserve audiovisual material in need of reformatting.

At the end of the project, the recordings were added to the Berkeley Library Digital Collections, but there were many inconsistencies and a lack of archival context for these materials. This necessitated a careful review of the digital objects and archival collection information to note what information existed in each system and where there were discrepancies.

- Catalog

- Problem

- Catalog records did not include digital material

- Some material did not have item-level catalog records

- Solution

- Updated collection level records and item-level records to reflect digital material

- Problem

- Finding aid

- Problem

- Some audiovisual material was separated from original collections or appeared in multiple resource records

- Some recordings did not have archival objects

- Solution

- Archival objects confirmed, moved, or created in ArchivesSpace

- Digital objects created in ArchivesSpace linking out to Digital Collections records

- Problem

- Digital Collections

- Problem

- Objects had incorrect collection names in some cases

- Many items did not have links to their catalog records or finding aids

- Solution

- Reviewed and resolved metadata issues

- Added links in Digital Collections to connect digital object with catalog record and finding aid

- Problem

This project is a prime example of “closing the loop” – circling back to the system of record, augmenting metadata, and ensuring that the various systems we employ connect to one another. It is only at the closing of this loop that we can truly consider a digitization project complete.

Delivering Archives and Digital Objects: A Conceptual Model (DadoCM)

This approach is supported by the emerging Delivering Archives and Digital Objects: A Conceptual Model (DadoCM). This model acknowledges that while digital repositories are largely designed for managing single discrete objects, archival principles are focused on efficiently describing materials in the aggregate. This model is centered on facilitating access and provides a framework which aims to resolve the inherent tensions in archival description of digital collections through a series of guiding principles and technical structures. UC Berkeley Library’s maría a. matienzo, Head of the Application Development Services Department, is a contributor to the DadoCM and she has been a helpful resource in conceptualizing DadoCM.

Two core ideas of DadoCM that we can apply to our work:

- The meaning of an individual record becomes impoverished when it is removed from its context.

- Information may be displayed in multiple places, but it must only be created and updated in one, canonical system of record.

The DCU’s focus on “closing the loop” lays down the foundation of DadoCM by keeping materials described within the context of their collections as well as maintaining connections through our canonical system of record, ArchivesSpace. We hope to continue implementing the DadoCM framework in our practices.

Completed Loops

During FY 2024/2025, Leah added 891 digital objects to ArchivesSpace. The following finding aids were republished by Leah to include newly added digital objects from ArchivesSpace.

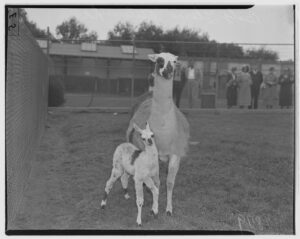

- Sierra Club records

- Urban Habitat Program records

- Emanuel Fritz papers

- Sierra Club Southwest Office records

- David Ross Brower Motion Picture Collection

- Sierra Club California Legislative Office Records

- Edgar Wayburn papers

- Howard W. Steward motion pictures

- California Gold Rush letters

- William Randolph Hearst, Jr. Photograph Collection

- George and Phoebe Apperson Hearst photograph collection

- Chinese in California

Looking ahead, we are excited to build on this momentum, and we are exploring how emerging technologies can enhance discovery and access to our collections. We are also continuing to learn from and contribute to our vibrant digital archives community. Our collaboration with our campus stakeholders is the cornerstone of this work, and we are eager to continue this journey together.

Post written by Christina Velazquez Fidler and Leah Sylva