Tag: interviews

The Oral History Center Presents the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project

The Oral History Center is proud to announce the launch of the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project, featuring 100 hours of oral history interviews with 23 Japanese American narrators who are survivors and descendants of two World War II-era sites of incarceration: Manzanar in California and Topaz in Utah. The majority of these oral histories are live on the Oral History Center website, where you can learn more about the project and the interviews themselves.

Just a couple of months after the United States entered World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. This order authorized the government to forcibly remove more than 120,000 Japanese American civilians—even American-born citizens—from their homes on the West Coast, and put them into incarceration camps shrouded in barbed wire and patrolled by armed guards for the duration of the war. This imprisonment uprooted families, disrupted businesses, and dispersed communities—impacting generations of Japanese Americans.

Even as the intergenerational impacts of World War II-era incarceration still touch many Japanese American descendants today, some Americans remain unaware of this history. It was in the spirit of illuminating the wounds of incarceration that OHC interviewers Roger Eardley-Pryor, Shanna Farrell, and Amanda Tewes embarked on this series of oral histories to record the stories of child survivors and descendants. Using healing as a throughline, these life history interviews explore identity, community, creative expression, and the stories family members passed down about how incarceration shaped their lives.

The project began in 2021 with funding from the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant. The interviews were conducted remotely via Zoom due to the global COVID-19 pandemic. The OHC team gathered a group of stakeholders with ties to the community to advise the project. Dr. Lisa Nakamura, a clinical psychologist who is herself a descendant of the Topaz incarceration camp, led Healing Circles for the project narrators after their interviews to process the experience without the interviewers present.

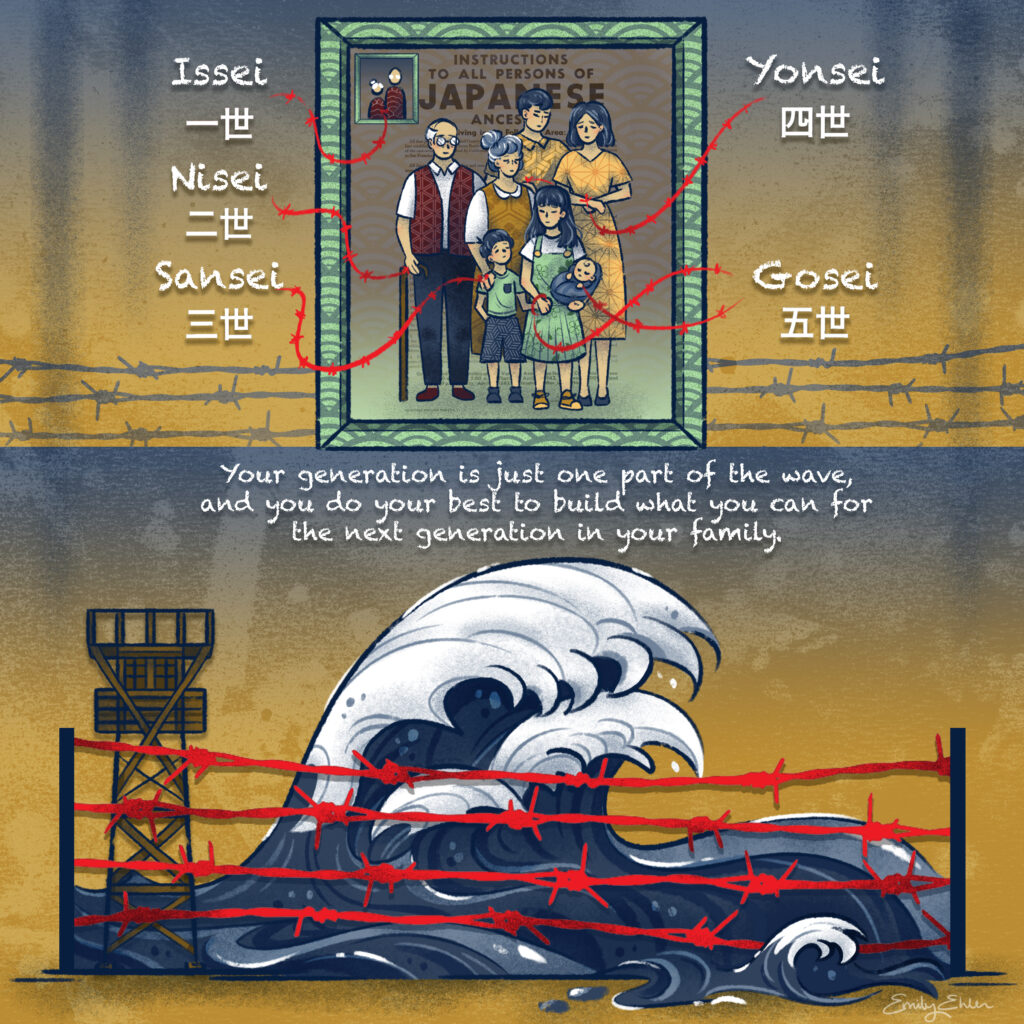

In addition to the oral histories, the OHC team produced a podcast as Season 8 of The Berkeley Remix to highlight the narrative themes that emerged from the interviews. They also commissioned artist Emily Ehlen, who created ten illustrations based upon stories and themes recorded in the interviews.

The podcast, “‘From Generation to Generation’: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration,” is a four-episode season featuring stories of activism, contested memory, identity and belonging, as well as artistic expression and memorialization of incarceration. It was produced by Rose Khor, Roger Eardley-Pryor, Shanna Farrell, and Amanda Tewes, and narrated by Devin Katayama. All four episodes are live on the OHC’s SoundCloud and in your podcast feeds.

Emily Ehlen’s artwork can be found on the OHC’s blog website and is available for download for educational purposes. Roger Eardley-Pryor sat down with Emily to learn more about her background, her work, and her process of creating these graphic illustrations.

Please explore the oral history transcripts and videos, listen to season 8 of The Berkeley Remix, and view Emily Ehlen’s artwork for more about the OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project.

A special thanks to the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant for funding this project.

The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government.

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you would like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. The Oral History Center is a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. As such, we must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

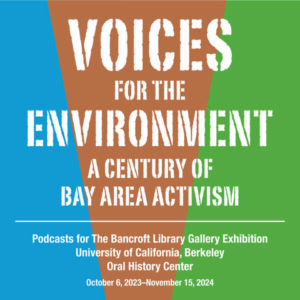

OHC Exhibit “Voices for the Environment” Curator Q&A

The Oral History Center is excited to announce the opening of Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism, a Bancroft Library Gallery exhibition that was curated by Todd Holmes, Roger Eardley-Pryor, and Paul Burnett. Voices for the Environment traces the evolution of environmentalism in the San Francisco Bay Area across the twentieth century. In three sections, it highlights how Bay Area activists have long been on the front lines of environmental change—from efforts to preserve natural spaces in the wake of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, to the midcentury fight for state regulations to protect San Francisco Bay shoreline, to more recent demands for environmental justice to address the disproportionate burden of pollution that sickened communities of color around the Bay.

We sat down with Eardley-Pryor and Holmes to ask them about their experience curating the exhibit, bringing the OHC’s interviews to life in The Bancroft Library’s gallery, and what they learned along the way.

Q: When you were originally thinking about this exhibit, which spans a century of Bay Area environmental activism, what topics, themes, or events were important for you to include?

TH: As historians, both Roger and I approached the exhibit through the lens of change over time, essentially asking the question, “How did what we’ve come to recognize as environmentalism evolve and change in the Bay Area over the twentieth century?” Combining our knowledge of both the oral history collection – which was to stand at the heart of the exhibit – and the environmental history of California, we selected the three stories we wanted to highlight fairly quickly.

First, we wanted to tell the story of Hetch Hetchy, the valley in Yosemite National Park that was dammed for San Francisco’s water system. This is a seminal event used in history classes across the nation to highlight the battle between two schools of environmentalism, preservationists like the Sierra Club’s John Muir, and conservationists like Gifford Pinchot of the U.S. Forest Service in the first part of the twentieth century. For the exhibit, we sought to use the Hetch Hetchy story to introduce visitors to preservation as the first form of environmentalism that took root in the Bay Area.

Second, we wanted to tell the story of Save The Bay, the movement initiated by three women from Berkeley to halt bay fill. Ultimately, that movement led to the creation of the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC), a state government agency to regulate development on the bay. Here we wanted to highlight how environmental concerns became embedded within the fold of government by the mid-century. BCDC stands as the first environmental agency in the United States, providing a precedent for other regulatory agencies on the state and federal level in the years that followed, such as the California Coastal Commission. Moreover, BCDC also operated within a framework that sought to balance environmental protection with economic development.

Third, we wanted to tell the story of environmental justice, a movement in the last part of the twentieth century that sought to put the health of people – particularly communities of color – within the environmental agenda. While environmental justice is fairly common today in discussions of environmental policy, the story of how it developed is not well known, and the Bay Area was one of the central places in the nation from which the movement took root.

REP: Todd and I worked to ensure that, in this exhibit, environmental activists could speak for themselves, and that visitors to the exhibit could actually hear the voices of activists recorded in their oral history interviews. The Audio Spotlight technology that allow people to hear interview clips in the gallery, the three videos Todd created with rare film footage and photographs, and the three podcast episodes we made with Sasha Khokha of KQED all make this exhibit something special that has never been done before in The Bancroft Library Gallery. For me, the people-power of communities of color demanding environmental justice, and the longtime leadership of women working for environmental protection were really important themes to include. Often, environmental history is told through the actions of men like John Muir, who does deserve credit for his early advocacy to protect nature through its preservation. The legacy of Muir and the ongoing work of the Sierra Club are important, and they remain so today. But Todd and I wanted to tell a deeper and broader history of Bay Area environmentalism, which shows how women and people of color have been central to the expansion and the evolution of environmental action over the course of the 20th century. I hope the stories shared in this exhibit help contextualize and make current environmental issues more meaningful—be it present-day preservation issues in 30 x ’30 campaigns, or conflicts over coastal regulations amid sea-level rise, or ongoing challenges to empower people of color in mainstream environmental movements.

Q: Did the themes you wanted to highlight change during the course of your research?

REP: We worked hard for over a year to bring this exhibit to life and to my memory, we agreed fairly early on about the three main narratives featured in the exhibit—the preservation of nature, reconciling environment and development, and environmental justice for communities of color. Over the course of our research, we changed the details of which particular oral history segment we might include here or there, or which image or document would best compliment the oral histories featured in each section of the exhibit. But as I recall, the exhibit’s main story arc remained steady from early in our curation process.

TH: Surprisingly, there was no change in the main topics / stories we wanted to highlight in the three sections of the exhibit. What our research did do was help expand on the themes within each to add more depth and nuance around community activism. For instance, in the first section we not only focused on the story of Hetch Hetchy, but connected it to activism around Save the Redwoods, which in turn highlighted the vital – yet often overlooked – role of women in the early preservation movement. Men like John Muir may have become the figureheads of environmentalism, and voted for such policies in government, but it was women who provided the grassroots momentum that put environmental concerns on the table. The same could be said for the third section on environmental justice. Our research uncovered a lot of different groups and experiences in the Bay Area grappling with environmental racism, from toxic sites in Richmond and what became known as the Silicon Valley, to debates with white environmental groups about even using the term “racism.” So in all, our research gave us a number of themes to spotlight and weave together throughout the exhibit

Q: The exhibit begins with the 1906 earthquake. Why did you decide to start there?

TH: This is another example of how research expanded the themes and stories of the three main topics we sought to feature in the exhibit. We wanted to highlight the story of Hetch Hetchy in the first section. Our research of the Hetch Hetchy battle forced us to upstream to the root cause – the 1906 earthquake and fire that destroyed 80 percent of San Francisco. At the time, San Francisco stood as the largest and richest city west of Chicago. In the wake of the disaster, the rebuilding effort posed a tremendous threat to the natural resources of the state. Ancient redwood forests throughout the Bay Area and along California’s north and central coast were targeted for timber, just as the Hetch Hetchy Valley was eyed for water and hydro-electric power. Thus, these rebuilding efforts proved the impetus of the early activism to preserve California’s environment.

REP: The drowning of Hetch Hetchy Valley—despite it being located within Yosemite National Park—is such a powerful and classic story in environmental history, and it occurred because the 1906 earthquake and fire destroyed San Francisco. Amazingly, Todd found several oral histories in our collection with survivors of the earthquake and fire who recall their experiences of it when they were children. In The Bancroft Library, Todd also found historic film footage, recently digitized, that shows San Francisco still aflame just after the earthquake. Putting those oral histories together with this footage make for a captivating start to the exhibit.

But what I didn’t realize until working on the exhibit was how the preservation of redwoods was also connected to how the earthquake and fire destroyed San Francisco. After the fire, lumber companies promoted California’s fire-resistant coastal redwoods as a means to rebuild the devastated city. In turn, environmentalists redoubled their efforts to preserve special groves of those ancient redwood trees. It suddenly made sense to me how Muir Woods National Monument was established in Marin County just a few years after the 1906 earthquake. Additionally, we wanted our exhibit on Bay Area environmentalism to highlight the Sierra Club, which was founded in San Francisco in 1892 and has since become one of the most influential environmental organizations in the nation. The Oral History Center has conducted oral histories with Sierra Club leaders since the early 1970s, and several activists, like William Colby, Ansel Adams, and David Brower, discussed in their oral histories how the fate of Hetch Hetchy continues to inform ongoing preservation efforts. So, in many ways, the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire helped ignite the spirit of preservation that still informs environmental activism, both in the Bay Area and across much of North America.

Q: What role does oral history play in the exhibit?

REP: Oral history is the beating heart that gives life to this exhibit! We scoured several scores of Oral History Center transcripts for captivating stories about Bay Area environmental activism. David Dunham helped us obtain digitized versions of those oral history recordings. We then used The Bancroft’s traditional paper, photograph, and film collections to complement the oral history narratives that we featured in the exhibit. Christine Hult-Lewis and Lorna Kirwan helped us explore several of those archival collections, and Theresa Salazar pointed us to the excellent Urban Habitat Program Records, 1970-2001, which are displayed in our exhibit. Ultimately, the exhibit offers a multi-sensory experience where visitors can engage audio recordings, film footage, oil paintings, photographs, pamphlets, posters, descriptive text, and they can even hold the hardbound oral history transcripts featured in the exhibit. But certainly, oral history is the centerpiece of the exhibit.

TH: In short, everything! This is the first exhibit curated by the Oral History Center, and the first in-depth effort to showcase both the oral history and other archival collections of The Bancroft Library. Each section features oral histories about the main topic in three ways. Edited oral history segments are played in each section through an Audio Spotlight speaker, and accompanied with a video that shows captions as well as related photographs and archival footage. The oral histories are also available through a three-episode podcast, narrated by Sasha Khokha from KQED San Francisco. The podcast episodes, available online and in the gallery by scanning a QR Code, offer a deeper dive into the stories of each section. Lastly, we used oral histories quotes in the labels of the exhibit material to add further detail and context.

Q: The 1960s and ’70s were two very productive decades in terms of environmental activism. Did the oral histories that you encountered from the OHC’s collection make you think differently about this period, or illuminate something new?

TH: In my view, the oral histories we used in the exhibit helped place the activism of the 1960s and 1970s in better context. For instance, we often think of the “environmental movement” as arising around the late 1960s / early 1970s. Yet, this view completely overlooks the activism of men and women around preservation in the first couple decades of the twentieth century. It also overlooks the vital work of Sierra Club executive director David Brower, whose activism throughout the 1950s and 1960s staved off numerous developments and led to the establishment of ten new national parks. In many respects, I think the oral histories featured in this exhibit pushed me to think about a “long environmental movement” that gained traction in the halls of government during the 1960s and 1970s. I think the exhibit also highlights how the Civil Rights Movement and environmental movement came to intertwine by the end of the decade to form environmental justice, which was an area I felt fortunate to learn more about through this project.

REP: Actually, rather than the 1960s and 1970s, the oral histories we included in the exhibit helped me realize the importance of the 1980s and 90s to the expansion and evolution of environmentalism. Without a doubt, activity surrounding Earth Day in 1970 was a key inflection point in environmental history, inspiring new environmental laws and a new generation of environmental activists. But the oral histories in our exhibit tell how Bay Area activists laid the early groundwork at least since the early 20th century for later environmental regulations, and how activists in the final decades of the 20th century worked to include all people in environmental protections, especially communities of color who suffered the most from industrial pollution.

Q: You put together additional material, like a podcast and class workbook, to accompany the exhibit. How do you hope people will use these materials?

TH: For the past couple years, the Oral History Center has been working on ways to get our collection into the K-12 education space. We developed additional materials, such as the class workbook and podcast, to serve as educational resources for K-12 classrooms, as well as undergraduate courses.

REP: The podcasts and educational workbook can be used anywhere—while visiting and experiencing the exhibit in person, or at home or in classrooms. We hope people use those additional materials long after the exhibit closes in November 2024!

Q: What do you hope that people take away from the exhibit?

REP: I hope exhibit visitors sense the importance, power, and potential of oral history. I hope they see how the Oral History Center’s work to record the lived experiences and reflections of people through oral history creates invaluable records that helps us better understand where we’ve come from and helps us make sense of our experiences today. I also hope visitors realize the importance of Bay Area activists in shaping the evolution of environmentalism over time. And I hope visitors hear how the actions of Bay Area people in the past, as told in their own words, helped define our experiences in the Bay Area today. Given today’s grave threats to our environment and to our democracy, I hope visitors appreciate how environmental activism remains an ongoing process that is shaped and renewed by average people like them who engage in civic activism. I also hope the oral histories featured in this exhibit—and the many, many more that are preserved in the Oral History Center collection—help inspire people to shape and renew environmentalism today and in the future.

TH: I hope visitors come away from the exhibit with a better understanding of how environmentalism evolved and changed over the century, and that it has a long history in the Bay Area. Moreover, I hope the oral histories featured in the exhibit highlight the change brought on by everyday people. It was the activism of men and women that led to protected redwood forests and the creation of state and national parks. It was the unwavering dedication of three women from Berkeley that stopped fill projects in San Francisco Bay and led to the nation’s first government-run environmental agency. And it was the collective action of communities of color that put justice within the environmental agenda, and on the dockets of policymakers. Ultimately, I hope visitors, young and old, walk away with the idea that change comes about through everyday people.

“Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism,” an Oral History Center exhibit in The Bancroft Library Gallery

We’re excited to announce the opening of Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism, a Bancroft Library Gallery exhibition that was curated by Todd Holmes, Roger Eardley-Pryor, and Paul Burnett of the Oral History Center. Voices for the Environment traces the evolution of environmentalism in the San Francisco Bay Area across the twentieth century. In three sections, it highlights how Bay Area activists have long been on the front lines of environmental change—from efforts to preserve natural spaces in the wake of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, to the midcentury fight for state regulations to protect San Francisco Bay shoreline, to more recent demands for environmental justice to address the disproportionate burden of pollution that sickened communities of color around the Bay.

Our Voices for the Environment exhibit is the first major effort in The Bancroft Library Gallery to showcase oral history alongside the traditional archival collections of The Bancroft Library, with the oral history collections leading the way. The exhibit still features historic photographs, pamphlets, post cards, and posters selected from several collections of The Bancroft’s physical archives. But for the first time in this gallery, our Voices for the Environment exhibit also includes three installations of special Audio Spotlight technology where you can listen to never-before-heard oral history recordings with Bay Area environmentalists, while simultaneously watching three videos edited by Todd Holmes that feature historic photographs and rare film footage from The Bancroft’s digital collections. Additionally, as a complement to the exhibit, curators Todd Holmes and Roger Eardley-Pryor created an educational workbook, so students of all ages can learn about the environmental movement by engaging with the themes and primary sources on display. Through these efforts, the Oral History Center hopes Voices for the Environment will have a life beyond its yearlong run.

For an even deeper dive, you can also scan a QR code in the gallery, or click the following link, to hear three Voices for the Environment podcast episodes produced in partnership with Sasha Khokha of KQED Public Radio and The California Report Magazine. The podcast episode for section 1 of the exhibit, titled “A Preservationist Spirit,” traces the environmental activism that arose amid the rebuilding efforts of San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake and fire, efforts that came to target the state’s ancient redwood forests and the beloved Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park. The episode features historic interviews from the Oral History Center archives including segments from the “Growing Up in the Cities” collection recorded in the late 1970s by Frederick M. Wirt, as well as oral history interviews with Carolyn Merchant recorded in 2022, with Ansel Adams recorded in the mid-1970s, and with David Brower recorded in the mid-1970s. The oral history of William E. Colby from 1953 was voiced by Anders Hauge, and the oral history of Francis Farquhar from 1958 was voiced by Ross Bradford. This first episode also features audio from the film Two Yosemites, directed and narrated by David Brower in 1955. The podcast episode for section 2 of the exhibit, titled “Tides of Conservation,” tells the story of the Save San Francisco Bay movement and the creation of the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC), one the nation’s first environmental regulatory agencies. The episode features segments from oral history interviews with Save The Bay founders Esther Gulick, Catherine “Kay” Kerr, and Sylvia McLaughlin recorded in 1985; as well as interviews with BCDC executive director Joseph Bodovitz and chairman Melvin B. Lane, both recorded in 1984. And the podcast episode for section 3 of the exhibit, titled “Environmental Justice for All,” spotlights efforts by communities of color to place the health of people within the environmental agenda, including creation of new environmental organizations like the West County Toxics Coalition, the Urban Habitat Program, and APEN (Asian Pacific Environmental Network), all founded in the Bay Area. The episode features segments from oral history interviews with Carl Anthony, Pamela Tau Lee, Henry Clark, and Ahmadia Thomas, all recorded in 1999 and 2000.

The Voices for the Environment exhibition space was designed by Gordon Chun and is free and open to the public Monday through Friday between 10am to 4pm from Oct. 6, 2023 to Nov. 15, 2024, in The Bancroft Library Gallery, located just inside the east entrance of The Bancroft Library.

We hope you come to campus and experience it!

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. While we receive modest institutional support, we are a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. We must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

Oral History Center Celebrates “Graduates”

Spring is a time of year when things begin anew. Flowers bud new petals, days have new length, and college graduates embark on new careers. It’s also a time when we at the Oral History Center celebrate an exciting phase of our narrators’ lives: a new life in our archive, where their story will live on in perpetuity. Not only can a narrator’s loved ones, friends, and colleagues access their interviews for years to come, students, researchers, and scholars can learn something about a time and a place, illuminating an aspect of history they might not have previously considered.

One way the UC Berkeley Oral History Center (OHC) likes to usher in this new phase of a narrator’s life is to have a “graduation” ceremony to honor their participation in the oral history process. Traditionally, we did this in person at the Morrison Library here on UC Berkeley’s campus, but like many things, we’ve had to adjust in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, we like to list their names and the projects for which they were interviewed online and in our newsletter so that all those in the OHC’s community can celebrate their contributions with us from near and far.

Please join us in expressing our appreciation for our latest cohort of narrators, spanning from fall 2021 to spring 2023. We are grateful to have their voices in our collection and their stories a new part of the historical record.

We also want to thank the OHC team—Paul Burnett, David Dunham, Roger Eardley-Pryor, Shanna Farrell, Todd Holmes, Jill Schlessinger, and Amanda Tewes—for their work in making these interviews come to fruition, along with the support from our student employees, who are a valuable part of our process: Max Afifi, Mollie Appel-Turner, Hue Bui, Mina Choi, William Cooke, Georgia Cutter, Nikki Do, Adam Hagen, Jordan Harris, Vivien Huerta-Guimont, Ashley Sangyou Kim, Ricky Noel, Deborah Qu, Mela Seyoum, Lauren Sheehan-Clark, Joe Sison, Erin Vinson, Shannon White, Serena Williams, and Timothy Yue.

Bravo, Oral History Center Class of 2023!

Anchor Brewing Co.

Mark Carpenter

Gordon MacDermott

Fritz Maytag

Linda Rowe

Bay Area Women in Politics

Louise Renne

Ruth Rosen

J.J. Wilson

California Business

Fred Martin

California Cannabis

Oliver Bates

California State Archives State Government Oral History Program

Wesley Chesbro

Fran Pavley

Lois Wolk

Bill Lockyer

Chicana/o Studies

Adele de la Torre

Ignacio García

East Bay Regional Park District

Ira Bletz

Ginny Fereira

Neil Havlik

Carol Johnson

Doug McConnell

Ruth Orta

Bethia Stone

Jeff Wilson

Mark Taylor

Mae Torlakson

Tom Torlakson

Will Travis

Nancy Wenninger

Environment/Natural Resources

Mary D. Nichols

Getty Research Institute’s African American Art History Initiative

Marion Epting

Maren Hassinger

Leslie King-Hammond

Thaddeus Mosley

Sylvia Snowden

William T. Williams

Vickie Wilson

Richard Wyatt

Getty Trust

Jerry Podany

Uta Barth

Tobey Moss

Katrin Henkel

Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives

Miko Charbonneau

Bruce Embrey

Hans Goto

Patrick Hayashi

Jean Hibino

Mitchell Higa

Roy Hirabayashi

Carolyn Iyoya Irving

Susan Kitazawa

Naomi Kubota Lee

Ron Kuramoto

Jennifer Mariko Neuwalder

Kimi Maru

Lori Matsumura

Alan Miyatake

Margret Mukai

Ruth Sasaki

Steven Shigeto Sindlinger

Masako Takahashi

Peggy Takahashi

Nancy Ukai

Hanako Wakatsuki-Chong

Rev. Michael Yoshii

Moore Foundation

Edward Penhoet

Kenneth Siebel

James C. Gaither

National Park Conservancy

Greg Moore

Sierra Club

Rhonda Anderson

Bruce Nilles

Verena Owen

Rita Harris

Resources and Planning

Anders Hauge

San Francisco Politics

Norman Yee

University History

Doris Sloan

Carolyn Merchant

Randy H. Katz

The Roots of the Oral History Center

by Charles Faulhaber, Interim Director of The Bancroft Library

As we bid farewell to 2021, I’ve been thinking about the power of first-person accounts and the meaning of oral history within The Bancroft Library’s collections. Bancroft’s Oral History Center was founded in 1953 by Robert Gordon Sproul, President of the University of California, as the Regional Oral History Office, “regional” because there was one at Berkeley for northern California and one at UCLA for southern California.

In fact, however, Bancroft’s oral history roots lie much deeper than that. As early as the 1860s, San Francisco bookdealer Hubert Howe Bancroft, the founder of The Bancroft Library, was traveling extensively up and down the Pacific Coast and back to the East Coast in order to record “dictations,” his interviews with the men, and some women, who had made the West their home. In Utah he interviewed Mormon leaders while his wife, Matilda Griffings Bancroft, interviewed their wives. On a trip to Pennsylvania he interviewed John Sutter, bitter over the failure of the federal government to compensate him for the loss of his extensive land grants in the gold-rich foothills of the Sierra Nevada.

Later, as Bancroft’s plans for a monumental history of California and the American West—eventually 39 massive volumes—crystallized, he hired staff to record dictations with the Californios, the Spaniards and Mexicans who had colonized Alta California from 1769 onward, men like Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, the last Mexican commandant of the Presidio in San Francisco, as well as with native Americans, like Isidora Filomena, the wife of chief Solano of the Suisun tribe.

Bancroft believed that these contemporaneous oral accounts provided an essential complement to the written sources in his library, which he eventually sold to the University of California in 1905. This is the same philosophy that informs the activities of the Oral History Center today. The thousands of oral histories that have been recorded in the almost seventy years since the Center was founded inform and enrich the printed and manuscript documentation collected by Bancroft’s curators.

Thus the series of oral histories of Japanese Americans who were incarcerated during World War II has proved to be a fundamental resource for Bancroft’s current exhibition, “UPROOTED: The Incarceration of Japanese Americans,” which also draws from Bancroft’s extensive collection of documents, photographs, and family and personal papers. This exhibition commemorates the 80th anniversary of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, which ordered the incarceration of all Japanese Americans on the West Coast, including American citizens, some 113,000 individuals.

I invite you to visit this powerful exhibit at The Bancroft Library Gallery when it re-opens briefly from January 10-21 and then again from February 17, 2022 through June 30, 2022, and hear first-hand the words of the uprooted, preserved for posterity through oral history.

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library has interviews on just about every topic imaginable. You can find the interviews mentioned here and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. The Oral History Center preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public.

“Big Data as a Way of Life”: How the UCB Library Can Support Big Data Research at Berkeley

This post summarizes findings and recommendations from the Library’s Ithaka S+R Local Report, “Supporting Big Data Research at the University of California, Berkeley” released on October 1, 2021. The research was conducted and the report written by Erin D. Foster, Research Data Management Program Service Lead, Research IT & University of California, Berkeley (UCB) Library, Ann Glusker, Sociology, Demography, Public Policy, & Quantitative Research Librarian, UCB Library, and Brian Quigley, Head of the Engineering & Physical Sciences Division, UCB Library.

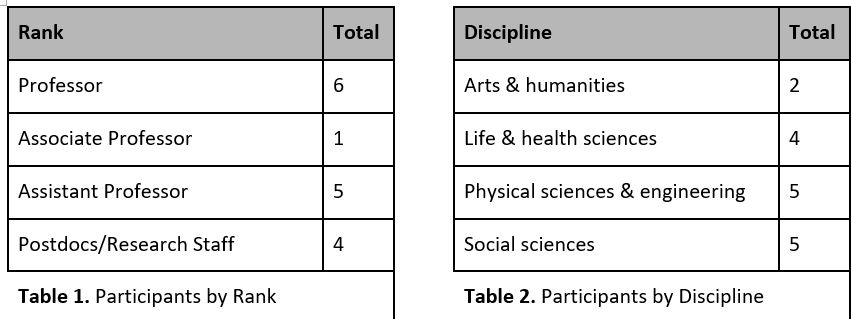

OVERVIEW:

In 2020, the Ithaka S+R project “Supporting Big Data Research” brought together twenty-one U.S. institutions to conduct a suite of parallel studies aimed at understanding researcher practices and needs related to data science methodologies and big data research. A team from the UCB Library conducted and analyzed interviews with a group of researchers at UC Berkeley. The timeline appears below. The UC Berkeley team’s report outlines the findings from the interviews with UC Berkeley researchers and makes recommendations for potential campus and library opportunities to support big data research. In addition to the UCB local report, Ithaka S+R will be releasing a capstone report later this year that will synthesize findings from all of the parallel studies to provide an overall perspective on evolving big data research practices and challenges to inform emerging services and support across the country.

PROCESS:

After successfully completing human subjects review, and using an interview protocol and training provided by Ithaka S+R, the team members recruited and interviewed 16 researchers from across ranks and disciplines whose research involved big data, defined as data having at least two of the following: volume, variety, and velocity.

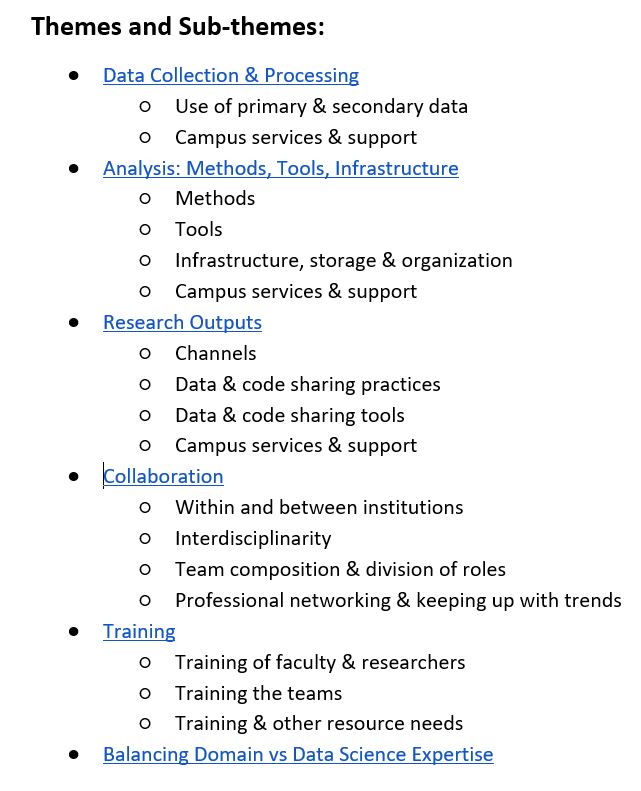

THEMES:

After transcribing the interviews and coding them using an open coding process, six themes emerged. These themes and sub-themes are listed below and treated fully in the final report. The report includes a number of quotes so that readers can “hear” the voices of Berkeley’s big data researchers most directly. In addition, the report outlines the challenges reported by researchers within each theme.

RECOMMENDATIONS:

The most important part of the entire research process was developing a list of recommendations for the UC Berkeley Library and its campus partners. Based on the needs and challenges expressed by researchers, and influenced by our own sense of the campus data landscape including the newly formed Library Data Services Program, these recommendations are discussed in more detail in the full report. They reflect the two main challenges that interviewees reported Berkeley faces as big data research becomes increasingly common. One challenge is that the range of discrete data operations happening all over campus, not always broadly promoted, means that it is easy to have duplications of services and resources — and silos. The other (related) challenge is that Berkeley has a distinctive data landscape and a long history of smaller units on campus being at the cutting edge of data activities. How can these be better integrated while maintaining their individuality and freedom of movement? Additionally, funding is a perennial issue, given the fact that Berkeley is a public institution in an area with a high cost of living and a very competitive salary structure for tech workers who provide data supports.

Here are the report’s recommendations in brief:

-

Create a research-welcoming “third place” to encourage and support data cultures and communities.

The creation of a “data culture” on campus, which can infuse everything from communications to curricula, can address challenges related to navigating the big data landscape at Berkeley, including collaboration/interdisciplinarity, and the gap between data science and domain knowledge. One way to operationalize this idea is to utilize the concept of the “third place,” first outlined by Ray Oldenburg. This can happen in, but should not be limited to, the library, and it can occur in both physical and virtual spaces. Encouraging open exploration and conversation across silos, disciplines, and hierarchies is the goal, and centering Justice, Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (JEDI) as a core principle is essential.

- The University Library, in partnership with Research IT, conducts continuous inquiry and assessment of researchers and data professionals, to be sure our efforts address the in-the-moment needs of researchers and research teams.

- The University Library, in line with being a “third place” for conversation and knowledge sharing, and in partnership with a range of campus entities, sponsors programs to encourage cross-disciplinary engagement.

- Research IT and other campus units institute a process to explore resource sharing possibilities across teams of researchers in order to address duplication and improve efficiency.

- The University Library partners with the Division of Computing, Data Science, and Society (CDSS) to explore possibilities for data-dedicated physical and virtual spaces to support interdisciplinary data science collaboration and consultation.

- A consortium of campus entities develops a data policy/mission statement, which has as its central value an explicit justice, equity, diversity and inclusion (JEDI) focus/requirement.

-

Enhance the campus computing and data storage infrastructure to support the work of big data researchers across all disciplines and funding levels.

Researchers expressed gratitude for campus computing resources but also noted challenges with bandwidth, computing power, access, and cost. Others seemed unaware of the full extent of resources that were available to them. It is important to ensure that our computing and storage options meet researcher needs and then encourage them to leverage those resources.

- Research, Teaching & Learning and the University Library partner with Information Services & Technology (IST) to conduct further research and benchmarking in order to develop baseline levels of free data storage and computing access for all campus researchers.

- Research IT and the University Library work with campus to develop further incentives for funded researchers to participate in the Condo Cluster Program for Savio and/or the Secure Research Data & Computing (SRDC) platform.

- The University Library and Research IT partner to develop and promote streamlined, clear, and cost-effective workflows for storing, sharing, and moving big data.

-

Strengthen communication of research data and computing services to the campus community.

In the interviews, researchers directly or indirectly expressed a lack of knowledge about campus services, particularly as they related to research data and computing. In light of that, it is important for campus service providers to continuously assess how researchers are made aware of the services available to them.

- The University Library partners with Research IT to establish a process to reach new faculty across disciplines about campus data and compute resources.

- The University Library partners with Research IT and CDSS (including D-Lab and BIDS) to develop a promotional campaign and outreach model to increase awareness of the campus computing infrastructure and consulting services.

- The University Library develops a unified and targeted communication method for providing campus researchers with information about campus data resources – big data and otherwise.

-

Coordinate and develop training programs to support researchers in “keeping up with keeping up”

One of the most-cited challenges researchers stated in terms of training is that of keeping up with the dizzying pace of advances in the field of big data, which necessitate learning new methods and tools. Even with postdoc/grad student contributions, it can seem impossible to stay up to date with needed skills and techniques. Accordingly, the focus in this area should be to help researchers to keep up with staying current in their fields.

- The University Library addresses librarians’/library staff needs for professional development to increase comfort with the concepts of and program implementation around the research life cycle and big data.

- The University Library’s newly formed Library Data Services Program (LDSP) is well-positioned to offer campus-wide training sessions within the Program’s defined scope, and to serve as a hub for coordination of a holistic and scaffolded campus-wide training program

- The University Library’s LDSP, departmental liaisons, and other campus entities offering data-related training should specifically target graduate students and postdocs for research support.

- CDSS and other campus entities investigate the possibility of a certificate training program — targeted at faculty, postdocs, graduate students — leading to knowledge of the foundations of data science and machine learning, and competencies in working with those methodologies.

The full report concludes with a quote from one of the researchers interviewed, which we team members feel encapsulates much of the current situation relating to big data research at Berkeley, as well as the challenges and opportunities ahead:

[Physical sciences & engineering researcher] “The tsunami is coming. I sound like a crazy person heaping warning, but that’s the future. I’m sure we’ll adapt as this technology becomes more refined, cheaper… Big data is the way of the future. The question is, where in that spectrum do we as folks at Berkeley want to be? Do we want to be where the consumers are or do we want to be where the researchers should be? Which is basically several steps ahead of where what is more or less the gold standard. That’s a good question to contemplate in all of these discussions.

Do we want to be able to meet the bare minimum complying with big data capabilities? Or do we want to make sure that big data is not an issue? Because the thing is that it’s thrown around in the context that big data is a problem, a buzzword. But how do we at Berkeley make that a non-buzzword?

Big data should be just a way of life. How do we get to that point?”

9/11 and Interviewing around Collective Trauma

“…I very rarely ask questions about 9/11 during oral history interviews, and I’ve been trying to grapple with why that is.”

As we approach the twentieth anniversary of 9/11, I’ve been reflecting on my own memories of that fateful day in September, and its impact on how I interview others about traumatic events. Indeed, I recently realized how deeply intertwined my thoughts about 9/11 are with my oral history practice.

The first time I spoke aloud about 9/11 – aside from discussing breaking news in the days that followed – was in my introductory oral history class with Dr. Natalie Fousekis at California State University, Fullerton in August 2009. This was nearly eight years after the original events, when the terrorist group al-Qaeda coordinated the hijacking of four passenger airplanes with the intent to crash them into major US targets. This led to a tragic loss of life and shook a sense of national security for many Americans.

As an exercise about collective memory, Natalie invited the class (from youngest to oldest) to share recollections of that day. Despite the age differences (approximately early twenties to early forties), as we went around the table, it was striking that roughly twenty different stories aligned so closely, as though we were all reciting the same narrative with slightly different words. With the exception of hearing the news while getting ready for high school, my own memories were much the same. This was, of course, in part due to the media coverage Americans saw of the Twin Towers falling over and over again, which helped create a collective memory of that day. But the similarity in omissions was striking, too. I don’t remember many people discussing the plane that hit the Pentagon or Flight 93, which crashed in the fields of Pennsylvania. Later dubbed Ground Zero, even in 2009, New York City dominated our memories of 9/11.

I also remember that though the mood in the classroom was somber, none of us cried or expressed an overwhelming sense of grief. Looking back, I wonder why there wasn’t more emotion around this discussion of such a traumatic moment. The eighth anniversary of 9/11 was only weeks away, and for those who had been teenagers in 2001, that day and the ensuing War on Terror had indelibly changed our lives. In part, maybe we were already trying to analyze our own experiences as oral historians rather than vulnerable individuals, interpreting what our collective memories meant rather than sitting with their personal heaviness. Or maybe this room of California students felt more removed from the horrors of that day due to physical distance from the sites on the East Coast. But it is also possible that even eight years later, we weren’t yet ready to address these memories as collective trauma.

In the more than a decade since this classroom discussion, I have conducted hundreds of oral history interviews – many of them discussing traumatic moments for individuals and the collective. Yet, I find it strange to reflect on the centrality of 9/11 to my early oral history training, as it has been a major pitfall in my own practice as an interviewer. About three years ago, while preparing an interview outline, I suddenly realized that my narrator’s work documenting and securing collections at a major arts institution coincided with this moment in history. Luckily the narrator agreed to share her memories, and we had a fruitful discussion about the ways in which, for a time, 9/11 impacted all levels of American culture. This experience helped me register that I very rarely ask questions about 9/11 during oral history interviews, and I’ve been trying to grapple with why that is.

One possibility is that I, like many others in the field, struggle with when an event gets to become “history,” and how we choose to memorialize it. To me, 9/11 feels like yesterday, not necessarily an historical moment upon which I need to ask narrators to reflect. And I am certainly guilty of collapsing historical timelines and not concentrating on the recent past, even during long life history interviews.

But I also suspect that my omission of 9/11 in interviews has a great deal to do with the traumatic nature of that day. Like many interviewers, I’ve sometimes been reluctant to introduce topics at particular points of an oral history for fear of creating a trauma narrative where there otherwise wasn’t. And until recent training, I was not even confident in my own skills tackling trauma-informed interviews. This hurdle has a clear solution: I need to prioritize discussing potentially traumatic topics like 9/11 in pre-interviews or introducing them in the co-created interview outline.

What is less clear is how to navigate my own trauma about 9/11. How do my own memories of that day impact my willingness to ask others about it? Am I too close to the subject to be able to speak with narrators about it? Quite possibly. But one complication for all interviewers is that unlike other traumatic events with a beginning and end date, 9/11 is an ongoing reality – even twenty years later. From the recent withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan to the wide reach of the Department of Homeland Security to heightened airport screenings, we are all still living with the consequences of 9/11, and the trauma has not actually ended.

Twelve years after that classroom exercise around 9/11 and collective memory, I can appreciate Natalie’s methods all the more. I’ve learned over the course of my oral history practice that even deeply personal narratives can include elements of collective memory, and it is important to recognize such common threads in our lives as interviewers, as well.

I often preach that oral history practitioners need to acknowledge our biases so that we can better overcome them or even use them to our advantage. For me, examining my blind spot around 9/11 has also encouraged me to think about incorporating more recent and ongoing historical events into interviews. Not only is this reflection an important addition to the historical record, it is part of our essential work to help narrators make meaning of their lives through oral history. Similarly, evaluating my own blind spot around 9/11 has helped me recognize the blind spots in the collective memory of that day – such as narratives that leave out Flight 93 or the attack at the Pentagon – and encouraged me to think about how oral history can help fill these gaps. As we recognize the twentieth anniversary of 9/11, this work feels more necessary than ever.

From the OHC Archives: Zona Roberts and Learning to Walk Backwards

by Annabelle Long

Annabelle Long is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center. She worked with Shanna Farrell during the Spring ’21 semester. Annabelle is a third-year History and Creative Writing student from Sacramento. She works as a conduct caseworker in the Student Advocate’s Office and enjoys going on long walks in Berkeley. You can find her on Twitter @annabelllekl.

The pocket of Berkeley bounded by Telegraph and Shattuck avenues is generally considered to be quiet and uneventful. Colorful Victorian houses line the blocks, gray apartment complexes full of Cal students loom over sidewalks, and telephone lines crisscross over each other, dividing the sky into irregularly sized rectangles and diamonds. I spend a lot of time in this part of Berkeley. I have my favorite houses, my favorite trees, my favorite views in every direction. I have my favorite alleys and blocks and moments in its history. I can’t pick a single favorite former resident, but Zona Roberts is high on the list.

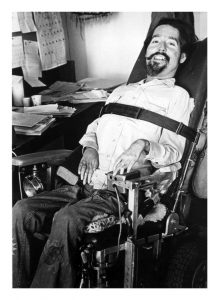

Zona existed in Berkeley as a mother before she existed here as a student. She lived with her sons Ed, Ron, Mark, and Randy in a pale green house she rented on Ward Street, a few blocks west of the hustle and bustle of Telegraph Avenue and a few blocks east of Shattuck. I often walk by her old house. It’s blue now, with red front steps, and it sits unassumingly behind a fence overgrown with flowers in the springtime. When Zona moved in, she had a ramp installed in the back to allow Ed to get inside. Ed Roberts, Zona’s eldest son and a political science major at UC Berkeley, was the first wheelchair user ever admitted to the school, and virtually nothing in the city was wheelchair accessible when he arrived on campus in 1962, including his mother’s home.

Ed Roberts

The green house, as it came to be known, acted as a sort of safe haven for the Roberts family and their friends. It was a family home for the community, not just Zona and her sons.

“It was a neighborhood of older families who’d lived there, a neighborhood of single-family homes, mostly, or two flats,” Zona said of the area, “The neighborhood was just changing as some of the older folks were dying off and some were moving away. A few younger people were moving in, but it was more or less an established neighborhood. But because of the racial composition and students in Berkeley, no one cared who went in and out of my house. The kids who came in or the Black students who visited and some lived, for a while, with me. There was no threat to their lives. There were none of those issues. It was just like a breath of fresh air to me. It was so nice not to have to worry about what might happen. I remember that vividly.”

Roberts Family

Zona, by all accounts, was an unflappable person. When she and her sons came to Berkeley, she was a recent widow, and had been Ed’s primary caretaker since he contracted polio and became a quadriplegic in 1953. She was a fierce advocate for all her sons and their needs and disliked being told what to do—she, as a learned expert in their likes and needs, felt that she knew best.

UC Berkeley promised a new world of opportunity for both her and Ed, when previously, his disability had meant neither of them was optimistic about what the future would hold, and her role as mother and caretaker left little room for imagining a life outside their home. But Berkeley was different; here, Ed was a student and leader, and eventually, so was she. In her oral history, when the conversation veered away from her time in Berkeley, she’d direct it back with references to the green house. The landscape of her college experience seemed to define it. She became acquainted with Berkeley alongside and behind Ed.

“One of the first days when I had taken Ed across and through campus, he was in a pushchair those days. He was quite tall and quite thin. We were going down into Faculty Glade and I had a hold of the back of his chair. It began to slip a little bit and I ran into a tree sort of deliberately to stop the chair, just the side of it, into this tree because I felt I was going to lose it. I don’t know whether my hands were sweaty, or the place was wet or what was happening. I think I finally learned how to do it backwards, where I’d walk down the hill backwards. I had better control.”

This anecdote, in my mind, speaks to the essence of Zona Roberts: ever present and adaptable to the needs of her son, caring and thoughtful, in the heart of Berkeley.

“In my senior year, I’d visit Ed up at Cowell. I remember one of the first times I walked through campus carrying my books, walked by Strawberry Creek, walking up to Cowell instead of coming in the station wagon from home or coming over to visit them. Here I was walking across campus on my way between classes and going up to visit and smiling a broad smile that I was now a student at Berkeley, also, and very proud of myself, and loving the campus and Strawberry Creek coming down through the middle of it. There’s some beauty in that Berkeley campus,” she said.

This feeling of reverence for Berkeley—for the atmosphere of casual intellectualism, for the exciting possibilities of being a student, for the sometimes-unbelievable natural beauty of the campus—is one I am intimately familiar with. I can only imagine how those feelings would be magnified for Zona, who, as a middle-aged widow and mother of four, never thought she’d live in Berkeley or become a student.

Zona was immensely proud to be a Berkeley student and to be Ed’s mother. She encouraged his involvement in activism and saw herself as an important backer of the disability rights movement; she saw herself as, first and foremost, an important backer of Ed.

“I saw my role at the office [UC Berkeley’s Center for Independent Living] as it became known as I did in Ed’s life, pushing Ed in front and being behind him,” she said of her involvement, “This was a place for people with visible disabilities to be visible, to be out in front. I found myself being in a supporting role, seeing that the office functions were going as smoothly as possible, seeing that there was food and heat and counseling and open doors and open access to information from us to the university and from the university to us. But somehow, we were in this together and it was a part of a wonderful movement. The time had come, and we were in the forefront of the movement and we were told this from all over the world. That was a glorious feeling. Hard work and glorious feeling.”

Zona Roberts

Zona Roberts worked hard to be the best mother she could be. Eventually, that meant becoming an integral part of a movement that was so much larger than any of them individually. If Ed Roberts was the father of the disability rights movement, Zona was the grandmother. She worked in the Center for Independent Living for years after its founding, and remains active in disability rights activism today, years after Ed’s death and well into her one hundred and first year of life.

I imagine the learning process of her activism was similar to learning to walk down the hill next to the Faculty Glade backwards, or modifying the old green house on Ward Street to make it accessible: sometimes slow-going, and certainly not without error, but always more than worth the trouble.

A Library Research Journey (Pandemic Edition)

Even beyond those who believe that librarians sit around and read books all day (which would be delightful but is most definitely not our reality), many are surprised to learn that librarians double as active researchers. This is especially true in settings where librarians are members of the faculty, but even where that isn’t the case, such as at Berkeley, librarians are born investigators and it carries over into wanting to find out about and add to knowledge of our settings.

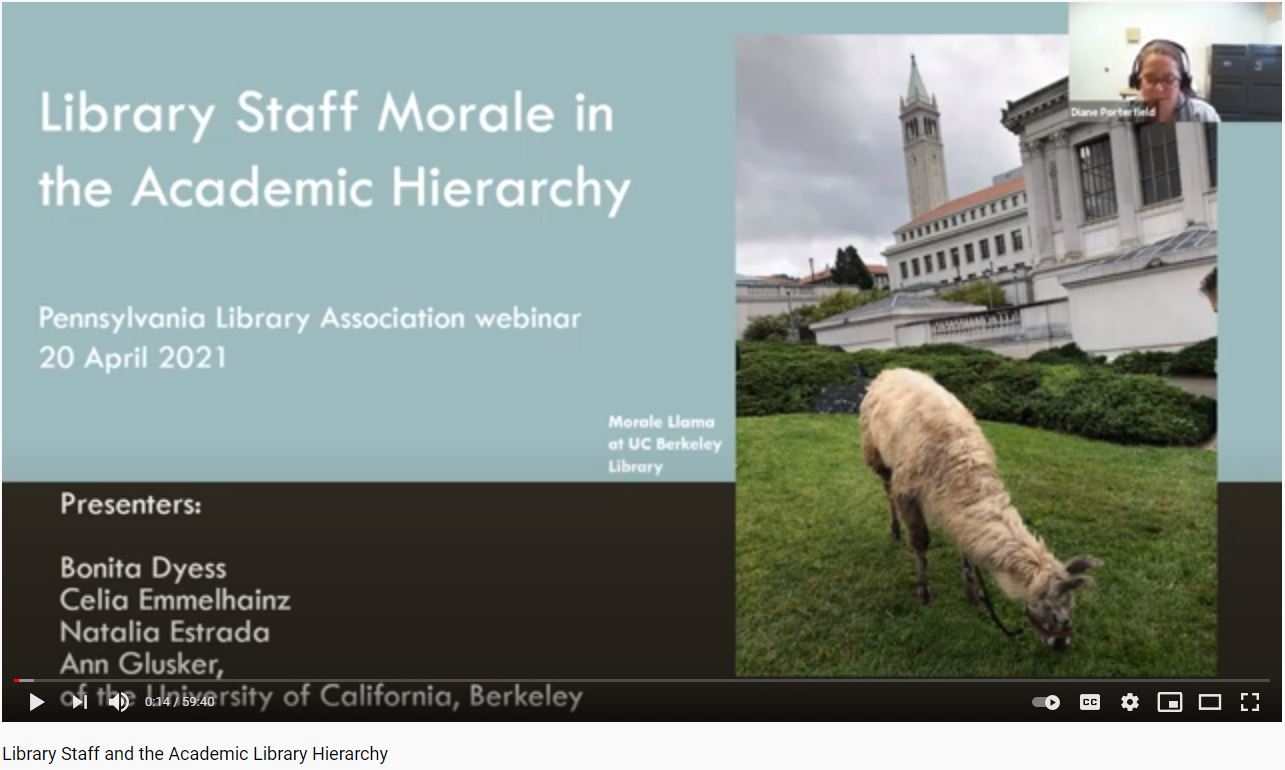

What does it look like to conduct library research? Glad you asked! In our case, it started with a conversation and an idea. Natalia Estrada (now Berkeley’s Political Science and Public Policy Librarian, then the Social Sciences Collection and Reference Assistant and in library school) and I were talking about how much we admired the work of Kaetrena Davis Kendrick. Kendrick wrote a foundational work in the study of librarian workplace morale, The Low Morale Experience of Academic Librarians: A Phenomenological Study, and it sparked many more studies on this topic. But, where were the studies of library staff experiences? We wanted to find out!

We were lucky to recruit two colleagues who added so much to the team: Bonita Dyess, Circulation/Reserves Supervisor at the Earth Sciences/Map Library, and Celia Emmelhainz, Berkeley’s Anthropology & Qualitative Research Librarian. First we applied for (and eventually got) funding for the research from LAUC (the Librarians Association of the University of California). This meant we could pay for transcribing our interviews, give the participants gift cards, and buy qualitative data analysis software. Then we applied for (and got) approval from the IRB (Institutional Review Board), making sure we were complying with processes for research with human subjects.

Here’s where the “pandemic edition” part comes in. All this planning and applying, starting in November 2019, took time; so, at the point we were actually ready to recruit participants, it was April 2020. We were sheltering in place, and not sure how this all would work (although it was probably better than having to go virtual in mid-stream)! Nevertheless, we hurled out information about and invitations to be part of the study to every list-serv, association, and friendly librarian we could think of, nationwide. We ended up doing 34 interviews with academic library staff from a range of locations and institution types (purposefully excluding the UC system), during a three-week period in May-June 2020. Due to COVID these were all online, either by phone or Google Meet (sort of like Zoom), and we asked a structured list of questions, with room for branching into other topics, or diving deeply. Celia trained a wonderful student to transcribe the interviews, and once we had those transcripts and stripped identifying information from them, we were off– coding away (using MAXQDA software), and drawing themes, quotes, recommendations, and other findings from the surprisingly rich information we’d collected.

Next—we had to start getting the information out into the world! Our eventual goal is to write a paper, or several, for publication. There are a number of library and information science journals out there that we are considering… but that takes time as well, and we wanted to start presenting our findings sooner. So, we did an “initial findings” presentation to the UC Berkeley Library Research Working Group, and then stepped into the big time with acceptance to present a poster at the 2021 Association of College and Research Libraries online conference (our poster got almost 600 views), and with a webinar we did for the Pennsylvania Library Association (both the poster and the webinar slides are available through the UC’s eScholarship portal). All our work to get to this point is hopefully now helping others.

And, a word about connecting with our participants. We were bowled over by their generosity with us and by all they had to say: much that we didn’t expect, and much that they were grateful someone was even asking about. It ended up that we had captured one of the last opportunities to get a snapshot of pre-COVID library staff life; people were still in limbo, and talked about their regular jobs before any lockdowns, for the most part. At that point most expected to be back in their libraries and all to be normal by the end of the summer 2020. We know now that that didn’t happen, and we know that library re-openings and staff roles in them have been challenging and sometimes contentious; we wish we’d known to ask for permission to re-interview our participants—even if only to check in with them. But how could we have known? We wonder how they are.

So now, we have papers to write, and thinking to do about how to take our questions into new avenues of research—because it’s a never-ending, and completely exciting process, and, we suspect, will be very different (easier? or not?) in the post-COVID landscape. Do you have ideas for us? We’d love to hear them! Or want to hear more about our morale study? Please get in touch with us at librarystaffmorale@berkeley.edu!

OHC’s Director’s Column: April 2021

Martin Meeker’s April 2021 Director’s Column

With the month of May fast approaching, I have been thinking a great deal about motherhood in general and my Mom in particular. Growing up, Mother’s Day was a big deal around my house — and my Mom wasn’t shy about letting us know that she appreciated the day off (from work at the office and home) and didn’t mind a little fuss being made for her. And she deserved it. My two sisters and I put her (and my Dad) through the paces. The entry of her kids into adulthood wasn’t so easy, either, with our cultural and political clashes, divorces, and career uncertainty. But our family persisted, largely due to my Mom, who willingly, or perhaps expectedly, assumed a peacemaker role. Lately, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought the family more closely together with regular Zoom reunions and an active, if usually silly, text group.

This week will mark the first time I get to lay my eyes on my mom in about 18 months — too long, considering that she’ll turn 80 this year. So, I’m thinking about the many, often difficult, roles that mothers are compelled to play and how those roles have changed. And, with COVID, have become more fraught and challenging.

When I begin to ponder something, arcane or universal, I’ll often turn to the OHC archive of 4000 oral histories with an eye to hearing first person accounts of real experiences on a given topic. Thankfully, our archive is replete with mainstream and remarkable stories of women who reflect on the joys, the work, the meaning, and the trials of motherhood.

Beverly Hancock Bouwsma, who was interviewed in 2001 for the UC Berkeley History Department project as a faculty wife, mused throughout her oral history of familial division of labor and the work of motherhood — in her case raising five children. When asked by OHC historian Ann Lage, “Did you enjoy motherhood?” Bouwsma replied, “Oh, I loved it. I did. I mean, sometimes it’s the worst thing in the world, but I always had a nice time with the children and cared desperately about them growing up. It seems like I didn’t, because when I hear now what they did, and I never knew about it, it seems like I must have been an awful mother. But I remember, at the time, I did what I thought you should do, and I really cared a lot.” This brief response articulates the love and frustrations and ambiguity many narrators in our collection reveal about motherhood — their recollections are rarely pat, especially when given the opportunity to reflect and speak at length.

Bay Area businesswoman Margaret Liu Collins, who was interviewed in 2011, recalls having two children with a husband who was abusive. Eventually the marriage ended and she raised the kids on her own, which kept her busy trying to build a business during the daytime, attending prayer meetings in the evening, and soccer games on the weekends. Then tragedy struck: her seven-year-old son was hit by a drunk driver. Collins recounted the moment, “It was 1979 sometime in October. I heard a siren going past my house because our house was on Belmont Canyon Road. The school was just across the street. We moved there from Cupertino because I had to travel a lot to Texas to do all my real estate, as well as go to Hong Kong and meet all my clients. I heard footsteps running onto the deck of our driveway, and somebody banged on the door. I had a really bad feeling that something was happening. The girl next door came and said, ‘Mrs. Liu, your son has been hit by a van and has been taken by the fire department to a hospital nearby’.” She continued, “When I went to Mills Hospital, he was in a coma. The doctor said he might never wake up. I was in pain. He was a brilliant child. It was my child. How could he pre-decease me? He had a whole future ahead. He had always lived with such enthusiasm, such curiosity. He loved people, and everybody loved him. He was generous. He was kind. He was giving. He could always solve problems. I still remember at that moment, I was feeling very sad.” Several months of treatment, uncertainty, and fear followed. Eventually, her son emerged from his coma and made a full recovery. She thanked God for his blessings but it was her devotion and love that brought her son back from the brink.

As well as recollections from women about their own experiences of motherhood, OHC’s collection contains thousands of memories of mothers by daughters and sons. Shirley Henderson, who was interviewed for our Rosie the Riveter / World War II Home Front project, remembered growing up in Berkeley in the 1930s admiring her mom for engaging in service activities outside the home: “My mother was the original community volunteer. She was a very capable and bubbly, outgoing woman. She did Girl Scouts; she was indefatigable at the church. I wonder what churches are going to be like when there are no more women to work as volunteers, which is about where the churches are now, almost. She ran a Sunday school class, a very large class of girls, because the girls were all so enthusiastic about the class that they brought their friends. My mother had them from the fourth grade through the twelfth grade, the same girls for that whole time. My mother had a very good third ear, and some of those girls had family troubles, and they were lucky to have my mother. I can remember being jealous of them because my mother gave them more attention than she gave to me. But I didn’t need it. That’s, of course, the other half, the flip side.”

These passages represent the slightest hint at the extensive archive of stories of mothers and motherhood in the OHC collection. While OHC has never embarked on an “oral history of motherhood,” by using our search tool, you can construct your own such archive by uncovering many more of these remarkable narratives of exceptional mothers. And we hope you do this Mother’s Day and beyond.

Find these interviews and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.