Oral History Center

Celebrating the Work of Freedom to Marry, Through Oral History

By Katie Gonzales

The Oral History Center’s Freedom to Marry collection features interviews from key members of the Freedom to Marry organization. Officially launched in 2003 by Evan Wolfson, the campaign worked to legalize same-sex marriage across the United States. The campaign originally worked on helping same-sex couples get married on a smaller case-by-case scale, as at the time, no state in the country had legislation protecting same-sex marriage. The first state to even do so was Massachusetts in 2004. Throughout the organization’s lifespan, same-sex marriage went from being legally unprotected on a state level to federally protected as an unequivocal right across the United States.

However, in June 2024, the Supreme Court countered this ruling in Department of State v. Muñoz, in which it declared that the right to bring a noncitizen spouse to the United States is not constitutionally protected. This ruling could be detrimental towards married same-sex citizens and noncitizens who would have to leave the United States, a country where their marriage is legal, back to a home country where it isn’t.

Given the June 2024 Supreme Court ruling, as well as this being Pride month, it’s a great time to look back on the work that Freedom to Marry did to legalize same-sex marriage. The lessons from the organization remain as important today as they were twenty years ago. When initially proposing the Freedom to Marry campaign to potential investors, Wolfson remembers:

I would be saying things to them like, look, if you just want to sprinkle some money around and do some ordinary building programs and helping people, I’m not the right person for you. And if you want to stay in your work up till now, which has been primarily in the Bay Area, and certainly only in California, not nationally, I’m definitely not the right guy for you. But if you really want to make a difference, what you really ought to do is support a campaign to win the freedom to marry. They went, “Marry?” “Yes, marriage. Marriage is the engine of change, marriage is what we’re going to have to be fighting for. You can do good work this way, but if you want to be transformational, you need to do this.”

One major battle that Freedom to Marry faced was when Proposition 8 passed in California. This ballot proposition intended to ban same-sex marriage measure passed in 2008. At the time, this was a massive blow to Freedom to Marry’s campaign, especially due to California’s reputation as a more progressive state. Tim Sweeney, a member of Freedom to Marry’s board of directors, recalls:

We were just devastated. It was devastating. Right? In California, the progressive beacon of the west, right? And we lost handily. It wasn’t close, which would have just taken a bit of the sting out of it. But what was interesting is the number of non-LGBT people who were outraged that their friends and family that they loved and cared about were basically being told you’re second-class citizens and your love is not legitimate. It created such a wave of we’re going to commit ourselves to fix this. And we have to be willing to be with them in their anger, invite them in in a new way, let them lead with us. All of that is hard to do, I think, in a social movement because you get worried they don’t really get it, their message is not your message, are they going to do some half measure, are they going to compromise, what do they know? But you got to kind of trust that they’re with you and you got to really in some cases step aside and realize, for instance, the message you may say to yourself or within the community is different than the one the non-LGBT community needs to hear. And maybe they need to have different messengers that just talk about the journey in a way that maybe an LGBT person wouldn’t sound authentic or real on. So that was just such an interesting moment. It’s almost like after Prop 8 we needed to step back a bit and let the world realize, “Wait a minute, what happened here? This is not okay.”

After the loss in California, support for LGBT rights increased due to the sheer amount of media coverage of the loss nationally. A Pew poll from 2010 cited that over 60% of Americans supported same-sex marriage, a drastic difference from polls in the 1990s that cited 60% of Americans against same-sex marriage. But by 2012, President Barack Obama made his support for same-sex marriage clear, stating that his views had “evolved” since his first presidential term. Thalia Zepatos, the Director of of Research and Messaging for Freedom to Marry recalls in her 2016 interview the impact of Obama’s statement:

I think really two things happened. One was that Governor [Martin] O’Malley really got involved in the campaign, but the big one was that our long-term effort to really engage the White House and President Obama came to fruition, you know not long before the election and President Obama made his statement in support of same-sex marriage, and within twenty-four hours, polling support for marriage among black voters in Maryland went up by twenty points. I mean, it was the biggest single day increase I’ve ever seen anywhere and I think it contributed just in a very great way.

By 2015, 37 states had legalized same-sex marriage, but it would not be a federal right until the Supreme Court case of Obergefell v. Hodges, which argued that same-sex marriage was a right under the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause and Equal Protection Clause. On June 26, 2015, the Supreme Court announced its ruling: same-sex marriage was guaranteed as a fundamental right. The same night, the White House was bathed in rainbow lights, an unmistakable show of support for the ruling. Jo Deutsch, Freedom to Marry’s federal director from 2011-2015, recounted this event:

It was a truth that, from every level, we had won. It was an acknowledgement from the President of the United States that our lives and our marriages mattered, in a just obvious way…This is the symbol of America and the symbol of the President of the United States, all in rainbow color. It was just breathtaking and so beautiful…We had come so far through our lives from asking can we walk down the street holding hands, or can we actually, in an introduction, say this is my wife? And now to this moment, there we were in front of the White House, in all of its colorful glory, with all of these people holding hands. I can’t tell you how many proposals we saw, with people just dropping to their knees right and left. It was like, another one dropping to their knees, and everybody started to clap. It was just phenomenal.

As the end of Pride month nears, it is important to remember that it hasn’t even been 10 years since the legalization of same-sex marriage in the United States. In many other countries around the world it is still taboo or even illegal. When we celebrate Pride month, it’s important to remember the work that many people and organizations did to ensure LBGTQIA rights, especially as they continue to face challenges. Celebrations can only happen as a result of triumph over tribulations, and should be remembered together.

Katie Gonzales is currently a third-year student at UC Berkeley studying English and Anthropology. She works as a student editor for the Oral History Center.

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

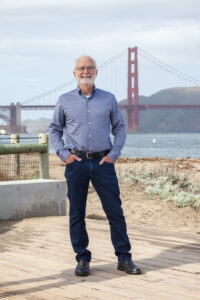

New Oral History from the OHC – Greg Moore: Executive Director of the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy

The San Francisco Bay Area is known for the kind of environmental advocacy that has become a model for regions around the country. There’s a long legacy, spanning decades, of people behind this work. Greg Moore is one of these people. Greg has dedicated his career to conserving public lands and making parks accessible for all. He, too, has become a model, someone to whom people throughout the country – and world – look for guidance.

Greg served as the executive director of the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy from 1986 until his retirement in 2019. The GGNPC was founded in 1981 and its mission is to preserve the Golden Gate national parks, enhance the park visitor experience, and build a community dedicated to conserving the parks for the future. But his work in the environmental sector began long before 1986, dating back to his time as a student at UC Berkeley in the newly-formed Conservation of Natural Resources School and College of Environmental Design, during the environmental decade of the 1970s when the Environmental Protection Agency was formed and regulatory laws, like the Clean Water Act, were passed. And even before that, when he was a ranger with the National Park Service.

I had the privilege of sitting down with Greg in 2022 to interview him about his life and work. In preparation for the sixteen hours I would end up spending with him, I spoke with a number of people who know him in different capacities – former fellow National Park Service rangers; as well as Conservancy board members, employees, and donors. One thing was clear: Greg is universally respected for his work and his collegiality. I kept hearing about how, as both a colleague and manager, he listened to people and carefully considered their perspectives. About how, as the executive director of the Conservancy, he wrote heartfelt letters to board members each year, letters that they all not only save, but cherish. About how he would write and perform in an annual musical parodying popular songs for year-end parties.

But what struck me the most was how present Greg was during each phase of our interview sessions. Whether we were discussing how he developed a love for music as a child; his studies at Cal and then later at the University of Washington; meeting his wife, Nancy, and raising their son; or his love for parks; the development of his career; managing a large staff and multi-million dollar fundraising campaigns; and working to make parks accessible for all, Greg took every question I asked seriously, responding sincerely and weaving in humor throughout.

Greg is perhaps best known for his work with the Conservancy. He played a role in the creation of the organization, which he discussed in more detail in his oral history, before becoming the executive director. There are an incredible array of projects on which he worked during his tenure with the Conservancy, like various habitat restorations, converting the Presidio from an Army base to a park, transiting Fort Baker from a military base into a national park, promoting citizen science through the Golden Gate Raptor Observatory, transforming Crissy Field into one of San Francisco’s crown jewels and creating the beloved Crissy Field Visitor Center, developing community partnerships and youth programs, and shepherding the Tunnel Tops project into existence. The list goes on.

The underlying theme of each of these projects was the drive to make parks accessible for everyone. “Parks for All” is the beating heart of the Conservancy’s mission. Here’s what Greg said about the origin of the mission:

“The ‘Parks For All’ came when the Conservancy was trying to think through how to simply and straightforwardly describe our mission. The Conservancy had a mission statement, but like many it was probably twenty-five to thirty words long, and I began thinking about how to put that in simple words that were very direct and, in some way, have the power-of-three impact. That’s when I began thinking, Well, of course, we’re about ‘parks.’ These are the physical places that we need to transform and enhance. Then we’re about ‘for all’ because these places are owned by every person in the United States as national parks, and then our final responsibility is ‘forever’ – to pass them from one generation to the next. It not only summarized our mission but almost described a theory of change that first you have the places and to make them for all youth to improve and enhance them. You have an opportunity to engage people in their enjoyment, in their stewardship, in their contributions for all, and then finally all the restoration work that cares for these places that you’ve enhanced and taken care of.”

Greg wanted to make sure people were aware that the parks existed, they felt comfortable there, and that they were relevant to the visitor’s life experience. He did this by bringing communities into planning conversations, implementing a bus route that would drive people from their neighborhoods to the parks and then back again, partnering with public libraries, and creating a multitude of programs – for kids, related to art, and citizen science for civilian park goers. Greg’s commitment to the Conservancy’s simple mission is what made the organization so successful and such an integral part of life in the Bay Area. And Greg’s interest in working with communities and listening to people – his colleagues, board members, donors, and park users alike – is what has made him such a towering figure in the Bay Area’s environmental movement.

It is with great excitement that we announce Greg Moore’s oral history is now publicly available.

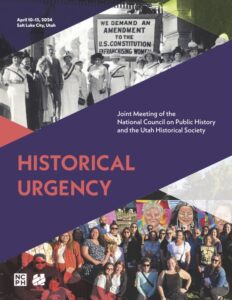

Oral History Center Presents Work at NCPH in Utah and Explores “Belonging” in Japanese American History

In April 2024, Oral History Center (OHC) interviewers Amanda Tewes, Shanna Farrell, and Roger Eardley-Pryor traveled to Salt Lake City, Utah, where we presented our work on the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project at the annual meeting of the National Council on Public History (NCPH). We also joined a pilgrimage to the central desert of Utah along with other public historians and several members of the Wakasa Memorial Committee, including survivors and descendants of the Topaz prison camp in Utah, one of the ten US government mass incarceration sites where Japanese Americans were unjustly imprisoned during World War II. Our experiences in Utah at NCPH and at Topaz reiterated how history remains a powerful and living force, and how oral history can help promote that power. Difficult questions about “belonging” appear throughout many of the oral histories in OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives project, and those same questions punctuated much of our time in Utah this past April.

“Historical Urgency” was the conference theme for this year’s meeting of the National Council on Public History (NCPH) in Salt Lake City, where some 740 attendees presented, networked, and learned together. Presentation topics included community engagement, particularly with communities whose histories face urgent existential threats; communicating the critical importance of history and historical thinking; discourse and dialogue in a time of extreme social polarization; exploration of oral history, especially the collection of oral histories from older generations; and repatriation of human remains and cultural objects. As noted by NCPH president Kristine Navarro-McElhaney, conference discussions highlighted how historians’ work for public audiences remains essential to the fabric of our society, especially during this time of political and cultural polarization—and yet historical perspectives, tools, and history workers themselves have increasingly come under threat. While urgency may seem in opposition to the often slow and deliberate work that oral historians and other public historians do to build trust and lasting relationships with the communities we serve, many of us cannot help but feel a strong sense of urgency and importance in our efforts to collaboratively excavate the past and elevate community stories in ways that help make meaning in the present.

We felt especially honored to share at this NCPH our work on the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project. Our roundtable presentation recounted the project’s origins, the trauma-informed interviewing approach we used with these oral histories, and some of emergent themes from the project’s interviews, like “belonging,” “art and expression,” “healing,” and “memorialization.” The roundtable’s discussion was moderated by Hanako Wakatsuki-Chong, the Executive Director of the Japanese American Museum of Oregon and a former National Park Service Ranger who recorded her own oral history as part of the project. Nancy Ukai and Masako Takahashi, both of whom also recorded oral histories as part of the project, attended and also presented at the NCPH conference in Utah, where they heard portions their own oral history interviews during our presentation. Our presentation included audio clips from season 8 of The Berkeley Remix podcast, “From Generation to Generation”: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration,” as well as graphic narrative artwork by Emily Ehlen, all based on oral histories recorded for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project.

Relatedly, during the NCPH conference, I (Roger Eardley-Pryor) joined other public historians for a tour of the Utah Museum of Fine Arts on the University of Utah campus to see a new exhibit titled Pictures of Belonging: Miki Hayakawa, Hisako Hibi, and Miné Okubo. The exhibition was curated by Professor ShiPu Wang of UC Merced and features over 100 paintings and works on paper by these three Japanese American women artists, all critically acclaimed with long and productive careers. Yet during World War II, both Hibi and Okubo were unjustly incarcerated in Utah at Topaz, along with Hayakawa’s parents. Pictures of Belonging follows the three artists’ prewar, wartime, and postwar art practices, sharing an expanded view of the American experience by women who used artmaking to take up space, make their presence and existence visible, and assert their own belonging. Many of the exhibit’s artworks are on view to the public for the first time. The exhibit’s titular theme of “belonging” resonated nicely with the Oral History Center’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project at UC Berkeley, and Okubo even earned her Master in Fine Arts degree in 1938 from UC Berkeley. Our tour of the art exhibit was co-led by Sarah Palmer, Head Exhibition Designer at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, and by Dr. Kristen Hayashi, Director of Collections Management & Access and Curator at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles. I am especially grateful I could tour Pictures of Belonging with Masako Takashashi, who herself is an outstanding multi-media artist, was born behind barbed wire at the Topaz prison camp in Utah, and who I worked with to record her forthcoming oral history interview for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project.

Our visit to the Utah Museum of Fine Arts also included another new exhibit titled Chiura Obata: Layer by Layer, which presents an in-depth look at the creation and conservation of Obata’s beautiful “Horses” silk screen painting from 1932. Chiura Obata was an esteemed artist and professor at UC Berkeley who was also incarcerated during World War II at Topaz in Utah, where he and Miné Okubo taught art classes for their fellow Japanese American incarcerees. Kimi Kodani Hill, the granddaughter of Chiura Obata, recently presented at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts on her grandfather’s life and work, and I’m grateful that during our recent meeting in Berkeley, prior to my own Utah trip, she shared stories with me about Obata’s silk screen exhibit. During the screen’s 2022 conservation treatment, conservators at Nishio Conservation Studio discovered that the four-paneled screen contained hidden full-scale preparatory charcoal drawings of the horses. In addition, they found that the screen’s internal layers were made of practice drawings by Professor Obata and his summer 1932 students. The recently conserved screen, the full-scale under-drawings, and a selection of the practice drawings were all on display at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, along with a short film on the conservation process, which itself is an artform. After we returned to the Bay Area, Kimi Kodani Hill provided a guided tour of another exhibition with forty of Chiura Obata’s watercolors, woodblock prints, and ink paintings from several decades of his life that are currently displayed through mid-July at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

On April 11, 2024, in Salt Lake City at the NCPH conference, Masako Takahashi and Nancy Ukai joined other members of the Wakasa Memorial Committee to present their own panel titled “Who Writes Our History?” This panel explored the life and tragic death of James Hatsuaki Wakasa, who was shot and killed while confined in Topaz eighty-one years earlier on April 11, 1943. Their panel also addressed urgent and ongoing challenges over descendant and survivor community consent and collaboration with the Topaz Museum following the recent discovery and excavation of the Wakasa Memorial Stone from the Topaz incarceration site in 2021. That massive, 1,000-pound stone memorial was erected in 1943 by Japanese American incarcerees at Topaz just after James Wakasa’s murder there. But US government authorities quickly demanded the memorial’s destruction in their effort to bury acknowledgement of Wakasa’s death from a bullet fired by a white, nineteen-year-old US soldier who was quickly acquitted of any crime. The Wakasa Memorial Committee’s NCPH presentation, which was standing-room only, featured short films and personal reflections on the life, death, memory, and now-contested stone memorial of James Wakasa.

Two days later, still in Utah, Oral History Center interviewers and several other public historians joined Ukai, Takahashi, and other members of the Wakasa Memorial Committee on a pilgrimage to the dust-strewn ruins of the Topaz site on the edge of the Great Basin in Utah’s central desert. The bus ride out to the remote site included watching historical films and sharing personal backgrounds and reflections amongst this group that had assembled from eight different states. Hours later, we arrived at a sparse, sun-bleached landscape encircled by distant snow-capped mountains. Much of the original barbed wire fence around Topaz remains today where some 8,000 Americans were unjustly imprisoned for years during World War II. Crumbled concrete foundations mark sites of now-gone guard towers where US soldiers aimed their guns down at the Japanese American prisoners, and from where they occasionally fired shots, like the one that pierced James Wakasa’s heart in 1943. At the Topaz site, we joined members of the Topaz Museum Board, including board president Patricia Wakida; Scott Bassett, board secretary and education director at the Topaz Museum; and Topaz descendant and board member Dianne Fukami. Together, we all participated in a ceremony organized by the Wakasa Memorial Committee to commemorate Wakasa’s death, as well as the 140 people who died behind barbed wire at Topaz, and the sixteen Japanese American soldiers drafted from Topaz who died during their World War II military service.

The Wakasa 81st Memorial Ceremony at Topaz began at block 36-7-D, where James Wakasa’s tar-paper barracks once stood. From there, we re-traced Wakasa’s steps across the dusty and now-hauntingly empty landscape to the western perimeter site of his murder, near where the Wakasa Memorial Stone once stood before incarcerated Japanese Americans, under government orders to destroy the memorial, buried it in 1943. An artist’s large recreation of the stone, this one blazing white and made of paper mache and wood, stood near the former burial site of the stone memorial before its removal in 2021. After a land blessing and words of remembrance from survivors born at Topaz, we encircled the artist’s stand-in memorial with name tags bearing the names of our own ancestors. Joshua Shimizu then sang in both Japanese and English the hymn “Rock of Ages,” which was also sung at Wakasa’s funeral in April 1943, and which offered deeper meaning for the missing original Wakasa Memorial Stone.

During the “Rock of Ages” hymn, ceremonial participants attached to the base of the art installation many colorful paper flowers that carried tags naming other Japanese Americans who died in Topaz. The paper flowers we carried to the ceremony were made by Topaz survivors and descendants in honor of the paper floral blossoms folded by imprisoned Japanese Americans at Topaz in lieu of actual flowers for James Wakasa’s 1943 funeral. Miné Okubo, the artist whose work we saw earlier at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, drew several illustrations of Wakasa’s funeral while she was incarcerated at Topaz, including drawings of imprisoned women folding paper flowers to adorn wreaths and crosses. On the desert floor in April 2024, white paper flowers also surrounded the excavation site where the Topaz Museum Board excavated Wakasa’s Memorial Stone in 2021. The Wakasa 81st Memorial Ceremony at Topaz simultaneously evoked absence and living memory. It was especially meaningful to me (Roger) to join Nancy Ukai and Masako Takahashi at the ceremony after having worked together to record their oral histories, in which they shared intergenerational memories about James Wakasa and more recent memories about the Wakasa Memorial Stone’s recent rediscovery and removal from that site.

After the ceremony at Topaz, the pilgrimage group boarded the bus and traveled sixteen miles to the handsome Topaz Museum, which opened in 2017 after decades of fundraising and planning in the small town of Delta, Utah. Once there, the pilgrimage group found their way to the back of the museum where we gathered to witness the actual Wakasa Memorial Stone, a one-thousand-pound rock now confined in a small enclosure. After paying our respects to the stone, we toured the Topaz Museum’s exhibits and collections, which include hundreds of artifacts, photographs, and oral histories, as well as 150 pieces of original artwork. The Topaz Museum’s core exhibit explores the complex story of the World War II Japanese American incarceration experience, especially as it transpired at Topaz. The exhibit begins with the racist laws that marginalized early Japanese immigrants, which lead eventually to the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. The exhibit extends into the traumatic impacts of their exile, with an obvious focus on the Topaz experience, and it concludes with an examination of the Constitutional violations that the incarcerees were forced to endure. I found the Topaz Museum exhibits to be impressive, interactive, and informative. The pilgrimage group then gathered a final time out back by the Wakasa Memorial Stone before boarding the bus and returning to Salt Lake City.

The emotional experiences throughout our time in Utah reminded me of William Faulkner’s line in Requiem for a Nun: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” The public history presentations on “historical urgency” at NCPH, the outstanding exhibits on Japanese American artists, the powerful pilgrimage to Topaz and the commemorative ceremony at the site of James Wakasa’s murder, which we shared with survivors and descendants of the prison camp eighty-one years from the date of Wakasa’s death, as well as our trip to the Topaz Museum to see its exhibits and the excavated Wakasa Memorial Stone all reminded us that history is still very much alive and shapes our present experiences. At both the Topaz incarceration site and at the Topaz Museum in Delta, we witnessed some of the still-simmering tensions between Topaz Museum Board members and members of the Wakasa Memorial Committee over what has happened and what will happen to the now-unearthed Wakasa Memorial Stone. Throughout all of those experiences in Utah, I kept thinking on the recurrent theme of “belonging,” including in the oral histories we continue to conduct in the Oral History Center’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project. “Belonging” carries multiple meanings and invites complex questions. Within what communities, or within which factions of communities, do we find and feel belonging? Throughout history, and up through the present, where have Japanese Americans found belonging? What about the physical artifacts of Japanese American history, like artwork created during World War II-era incarceration, or like the recently re-discovered Wakasa Memorial Stone? To whom do those objects belong? And importantly, who has the right to tell the history of artifacts, artwork, memorials, or lived experiences? To whom does this history belong?

Answers to questions of belonging are elusive because they’re always evolving. I do know, however, how grateful I feel to continue working with individuals and communities to record oral histories that empower narrators to share their own living memories and reflections on the past, and how the personal histories these interviews record will continue to shape our shared present moments. These experiences in Utah helped further inspire our ongoing work on the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project. We hope that you, too, can find inspiration and meaning in these stories, and that they might inform your own sense of belonging.

— Roger Eardley-Pryor, Oral History Center historian and interviewer

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. While we receive modest institutional support, we are a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. We must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

Oral History Center Partners in Yale Celebration of James C. Scott

On March 28, OHC historian Todd Holmes participated in the retirement celebration of James C. Scott at Yale University. For many academics around the world, Scott needs no introduction. He is the Sterling Professor of Political Science and Anthropology at Yale University; founder of the renowned Yale Agrarian Studies Program; and author of a series of groundbreaking books that over the decades have become mainstays across the fields of the humanities and social sciences. To be sure, this impressive scholarship not only earned him honors from nearly every corner of the academy, but also made him one of the most influential and widely read social scientists in the world. In 2022, Scott announced his retirement, drawing to a close an academic career that had spanned over five decades.

This past March, scholars and students alike gathered at Yale University to celebrate Scott and his extraordinary career—an event in which the Oral History Center was proud to participate. The OHC began working with Yale in 2018 on an oral history project to document both the career of Jim Scott and the history of the Agrarian Studies Program he founded in 1991. Led by OHC historian Todd Holmes and released in 2022, The Yale Agrarian Studies Oral History Project featured the full life history of Scott and shorter interviews with sixteen affiliates of the program. At the event, Holmes – a Yale alum and former graduate coordinator of the Agrarian Studies Program – presented bound volumes of the oral histories to the Yale University Library. In addition to the oral history presentation, the event also featured a screening of the documentary film, In A Field All His Own: The Life and Career of James C. Scott. Produced by Holmes, the film draws from the nearly thirty hours of oral history interviews conducted for the project to trace the intellectual journey of the award-winning social scientist from his childhood in New Jersey through each of the works he produced in his accomplished career. The film is available to the public on YouTube. It is also linked below.

Jim Scott expressed his appreciation for the event in his concluding remarks, noting how much he preferred a celebration of this sort – with film and discussion – over the typical academic retirement symposium, or Festschrift. The latter, in his view, “always seems like a memorial,” he joked with the audience, “and I assure you, I’m still here!” Always the humorist, he punctuated the point by announcing the forthcoming release of his book on Burma’s Irrawaddy River by Yale University Press, another noteworthy achievement for a scholar who turns 88 years young in December. Scott had discussed this project in his oral history, hinting that he still had something to say about rivers before he “hung up his coat.” It was a fitting end for an event celebrating an extraordinary career.

Additional Resources

James C. Scott: Agrarian Studies and Over 50 Years of Pioneering Work in the Social Sciences

Yale Agrarian Studies Oral History Project

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Bibliography for Trauma-informed Interviewing

In April 2024, the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives project team at The Oral History Center—Roger Eardley-Pryor, Shanna Farrell, and Amanda Tewes—had the opportunity to present about our project at the National Council on Public History conference in Salt Lake City. Since our presentation, we’ve gotten a number of questions about the literature we read related to trauma-informed interviewing, intergenerational trauma, and memory. Below is the bibliography we used, as well as some recent works. We hope this provides some guidance for your own work, and we’d love to hear from you if there are any articles or resources that have been helpful to you!

General

Cathy Caruth, Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996).

Mary Marshall Clark, “The September 11, 2001 Oral History Narrative and Memory Project: A First Report,” The Journal of American History 89:2 (September 2002): 569-579.

Mary Marshall Clark, “Resisting Attrition in Stories of Trauma,” Narrative 13:3 (October 2005): 294-298.

Lily Dayton. 2019 “Keep These Seven Lessons in Mind When Interviewing Trauma Survivors.” Center for Health Journalism. April 17, 2020. https://centerforhealthjournalism.org/our-work/insights/keep-these-seven-lessons-mind-when-interviewing-trauma-survivors

Andrea Eidinger, “Trauma and Orality: New Publications on Mass Violence and Oral History,” Social History 49:98 (May 2016): 187-196.

Steven High, Oral History at the Crossroads: Sharing Life Stories of Survival and Displacement (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2014).

Marianne Hirsch, “Family Pictures: Maus, Mourning, and Post-Memory,” Discourse 15:2, Special Issue: The Emotions, Gender, and the Politics of Subjectivity (Winter 1992-93): 3-29.

Marianne Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust (Columbia University Press, 2012).

Mark Klempner, “Navigating Life Review Interviews with Survivors of Trauma,” Oral History Review 27:2 (Summer/Fall 2000): 67-83.

Selma Leydesdorff, “Oral History, Trauma, and September 11, Comparative Oral History,” in edited volume September 11th-12th: The Individual and the State Faced with Terrorism (2013).

Carmen Nobel. 2018. “10 Rules for Reporting on War Trauma Survivors.” Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy. April 17, 2020. https://journalistsresource.org/politics-and-government/10-rules-interviewing-trauma-survivors/

Emma L. Vickers, “Unexpected Trauma in Oral Interviewing,” Oral History Review 46:1 (Winter/Spring 2019): 134-141.

Specific to Japanese American History

Jeffery F. Burton and Mary M. Farrell, “The Power of Place: James Hatsuaki Wakasa and the Persistence of Memory,” Discover Nikkei (June 13, 2021): http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2021/6/13/wakasa-1/

Jeffery F. Burton, Mary M. Farrell, Florence B. Lord, and Richard W. Lord, Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites (Tucson, AZ: Western Archeological and Conservation Center, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Publications in Anthropology 74, 1999).

Connie Y. Chiang, Nature Behind Barbed Wire: An Environmental History of the Japanese American Incarceration (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Roger Daniels, “Words Do Matter: A Note on Inappropriate Terminology and the Incarceration of Japanese Americans,” in Louis Fiset and Gail Nomura, eds. Nikkei in the Pacific Northwest: Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians in the Twentieth Century (Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press, 2005).

Roger Daniels, Sandra Taylor, and Harry L. Kitano, eds., Japanese Americans: From Relocation to Redress, Revised Edition (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1986).

Art Hansen, Barbed Voices: Oral History, Resistance, and the World War II Japanese American Social Disaster (Denver: University of Colorado Press, 2018).

William M. Hohri, Repairing America: An Account of the Movement for Japanese American Redress (Pullman, Washington: Washington State University Press, 1988).

Cathy Park Hong, Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning (New York: One World, 2020).

Stephen Holsapple, dir., produced by Satsuki Ina, Children of the Camps (Los Angeles, CA: AsianCrush, now Cineverse Corp., 1999).

Satsuki Ina, The Poet and the Silk Girl: A Memoir of Love, Imprisonment, and Protest (Berkeley, California: Heyday Books, 2024).

Donna K. Nagata, “Intergenerational Effects of the Japanese American Internment,” International Handbook of Multigenerational Legacies of Trauma, edited by Yael Danieli (New York: Plenum Press, 1998), p 125-139.

Donna K. Nagata and Wendy J. Y. Cheng, “Intergenerational Communication of Race-Related Trauma by Japanese American Former Internees,” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 73:3 (2003): 266-278.

Donna K. Nagata, Jacqueline H. J. Kim, and Kaidi Wu, “The Japanese American Wartime Incarceration: Examining the Scope of Racial Trauma,” American Psychology 74:1 (Jan. 2019): 36-48.

Donna K. Nagata, Jackie H. J. Kim, Teresa U. Nguyen, “Processing Cultural Trauma, Intergenerational Effects of the Japanese American Incarceration,” Journal of Social Issues 71 (2015): 356-370.

Lisa Nakamura “Seeking Meaning from the Past: Psychological Effects of Tule Lake Pilgrimage on Japanese American Former Internees and Their Descendants” (PsyD diss., Wright Institute Graduate School of Psychology, 2008).

Raymond Okamura. “The American Concentration Camps: A Cover-Up through Euphemistic Terminology,” Journal of Ethnic Studies 10:3 (1982).

Emiko Omori, dir., produced by Emiko and Chizu Omori, Rabbit in the Moon: A Documentary/Memoir about the World War II Japanese Internment Camps (Mill Valley, California, 1999).

Brandon Shimoda, The Afterlife Is Letting Go (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2024).

Karen L. Suyemoto, “Ethnic and Racial Identity in Multiracial Sansei: Intergenerational Effects of the World War II Mass Incarceration of Japanese Americans,” Genealogy 2:26 (2018).

Stephanie Takaragawa, “Not for Sale: How WWII Artifacts Mobilized Japanese Americans Online,” Anthropology Now, 7:3 (2015): 94-105,

Remembering Joseph E. Bodovitz (1930 – 2024)

On March 9, 2024, California lost one of its most revered public servants. For over forty years, Joseph Bodovitz stood at the center of the state’s regulatory process. He was the founding executive director of both the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC) and the California Coastal Commission. He was the executive director of the Public Utility Commission and headed up the California Environmental Trust. And before retirement, he agreed to serve as the project director for Bay Vision 2020. To be sure, his fingerprints could be found—one way or another—on some of the most important regulatory policies and decisions passed in California during the twentieth century—actions that would come to impact people throughout the Golden State, both then and now.

Joe, as most knew him, did not initially set his sights on government work. Born in Oklahoma City during the Great Depression, he studied English literature at Northwestern University, and after serving in the Korean War, earned a graduate degree in journalism at Columbia University. In 1956, he accepted a job as a reporter with the San Francisco Examiner, allowing him to return to a state and region for which the young Oklahoman had grown fond during his military service with the Navy. In the early 1960s, Bodovitz left journalism to take a position with the San Francisco Planning and Urban Research Association, an organization whose work in urban policy and development had become critical in the postwar boom of San Francisco. Such work proved a good fit for Bodovitz, whose reporting at the Examiner focused on politics and urban redevelopment in the city. By 1964, his reputation and work at SPUR had caught the attention of Eugene McAteer, a state senator from San Francisco who sought to establish a government study on regulating development and fill in the San Francisco Bay. Bodovitz not only joined that new group, he took the lead in crafting what would become known as the Bay Plan. When finished, he also agreed to serve as the founding executive director of the new regulatory agency that plan created, BCDC.

Bodovitz was entering uncharted waters in his role at BCDC. There was no precedent for this kind of environmental regulation back in 1965. In fact, BCDC was the first regulatory agency of its kind in the nation. That meant Bodovitz, with the help of commission chair Melvin B. Lane, was charged with creating a regulatory structure and policy from scratch. The task was daunting, especially in light of the array of forces they confronted throughout the process, from city mayors and wealthy businesses to citizen groups and environmental organizations. For Bodovitz, the principle that guided his work was striking a balance between economic development and environmental conservation. “People sort of had to confront the legitimate interests of both conservation and development,” he recalled in his 1986 oral history. “They may disagree on a particular permit or a particular issue, but no fair-minded person can say marshlands aren’t important. Similarly, no fair-minded person can say ports aren’t important to the Bay Area economy.” As he would often point out, balance was the underlying principle of BCDC: “There is a reason why conservation and development are in the name.”

In 1972, California voters approved Proposition 20, which created another historic agency: the California Coastal Commission. And as quick as the votes were tallied around the creation of the new state agency, Bodovitz and Lane were asked to bring their expertise from BCDC to the regulation of the state’s 1,100-mile coastline. In the familiar role of executive director, Bodovitz began to adapt the regulatory structure and policies of the bay to the coast, crafting what would become the coastal plan. His experience aside, the task proved even more daunting this time around. As Bodovitz recalled, the stakes were higher and the issues much more complex. “I don’t mean to make the BCDC planning sound simple because God knows it wasn’t; but relative to what we were dealing with in the Coastal Commission—it was simpler.” Ultimately, that work created a foundation for coastal regulation which would be studied around the world, and help made California one of the most pristine coastal regions of the Western Hemisphere. Fifty years later, the shorelines of Golden State still stand as a legacy of Bodovitz’s work.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Bodovitz’s public service on behalf of California continued. Shortly after he left the Coastal Commission in 1979, he was named executive director of the California Public Utilities Commission—the state agency charged with regulating utility companies throughout the state. Here, Bodovitz brought his experience and expertise to a range of important issues, from the breakup of telephone giant AT&T to the rising debate about deregulation and its impact on the state’s utility services. After his terms with the PUC, Bodovitz was tapped to head the newly created California Environmental Trust, as well as serve as the project director for Bay Vision 2020, which created a plan for a regional Bay Area government. In both organizations, Bodovitz provided invaluable leadership in helping to address a new set of environmental and development issues at the dawn of the twenty-first century.

It is an oft-stated adage among those in politics that civil servants are the unsung heroes of government. They conduct the research, staff the committees and commissions, and do the legwork that turns a written bill into an effective public policy. Joe Bodovitz was one of California’s unsung heroes. The Oral History Center had the privilege of conducting two oral histories with Bodovitz, documenting his experience and insights for future generations. The first, published in 1986 as part of the Ronald Reagan Gubernatorial Era Project, covered his experience at BCDC. Segments of this oral history are featured in the OHC’s Voices for the Environment exhibit and the accompanying podcast episode “Tides of Conservation.” The second oral history, published in 2015, offers an in-depth look at Bodovitz’s life and career. Both oral histories are available online through the links below.

Will Travis—another unsung hero of California in own right—perhaps said it best when writing the introduction for Bodovit’s 2015 oral history.

By having Joe as my friend for over 40 years and watching how other people treat him, I’ve learned why the Yiddish word mensch had to be created. A mensch is a person of integrity and honor, someone to admire and emulate, someone of noble character. In colloquial American English, a mensch is a stand-up kind of guy. Joe is a mensch.

World War II-era Japanese American Incarceration: A Guide to the Oral History Center’s Work

Anthology created by the Oral History Center

Research by Sari Morikawa, Serena Ingalls, and Timothy Yue, undergraduate researchers

After the entrance of the United States into World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, which mandated the forced removal of Japanese Americans from their homes on the West Coast into incarceration camps inland for the duration of the war. This forced removal uprooted families, disrupted businesses, and dispersed communities — impacting generations of Japanese Americans. The Oral History Center, or the OHC, and other archival collections in The Bancroft Library, feature several projects on this chapter of American history, comprising hundreds of interviews, photographs, artifacts, graphic illustrations, and podcasts for use by scholars and the public.

Find these interviews and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Find all the oral history projects mentioned here, along with more in-depth descriptions, on our projects page.

There are six parts to this collection guide to Oral History Center and other Bancroft Library resources:

- Projects about Japanese American incarceration

- Related projects

- Individual interviews

- How to search our collection

- Selected articles that highlight and synthesize this work

- Acknowledgements

Part 1: Projects about Japanese American Incarceration

Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives

The Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project is the OHC’s newest project on this subject, consisting of interviews with child survivors and descendants of those who were incarcerated. The project documents the ways in which intergenerational trauma and healing occurred after the United States government’s incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. Conducted by Roger Eardley-Pryor, Shanna Farrell, and Amanda Tewes, these interviews examine and compare how private memory, creative expression, place, and public interpretation intersect at sites of incarceration. Initial interviews focus on the Manzanar and Topaz prison camps, and pose a comparison through the lens of place, popular culture, and collective memory. Exploring narratives of healing as a through line, these interviews investigate the impact of different types of healing, how this informs collective memory, and how these narratives change across generations. The first set of interviews, comprised of 100 hours of oral history interviews with 23 narrators, continues to grow with interviews featuring child survivors and descendants of the Heart Mountain and Tule Lake prison camps.

“‘Dad, were you put in the camps?’ They didn’t talk about it. It was something you didn’t bring up…. He was honest but then he said, ‘But that happened in the past. You don’t need to dwell.’”

—Peggy Takahashi, on intergenerational silence related to her family’s incarceration

The project includes interpretive materials as well. Season eight of The Berkeley Remix, the OHC’s podcast based on oral history, explores themes from the project’s initial oral histories. “‘From Generation to Generation’: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration,” is a four-episode season featuring stories of activism, contested memory, identity and belonging, as well as artistic expression and memorialization of incarceration. In addition, ten graphic narrative illustrations created by artist Emily Ehlen vividly express the experiences of Japanese American incarceration during World War II and its effects on future generations. The interpretive materials, along with the oral histories, are available for use in classrooms.

Japanese American Confinement Sites

Interviews in the Japanese American Confinement Sites Oral History Project document the experiences of Japanese Americans who were incarcerated during World War II, including UC Berkeley students who attended college before or after the war. Themes running through these interviews include the experiences of forced relocation and incarceration; loss of property and livelihoods; identity; education; challenges faced after the end of the war; and emotional responses to their experiences. Many of the narrators went into fields such as public service, the military, advocacy, art, and education; some of them participated actively in the redress movement.

“Never again should there be such an event as a mass removal of an entire group of people without due process of law. … I try to pass that message on to as many people as I can.”

—Sam Mihara explains why he decided to become a speaker and share his stories

The voices of these narrators are brought to life in the slideshow: “The Uprooted: The Incarceration of Japanese Americans.” This slideshow was made to accompany the 2021–2022 exhibition in The Bancroft Library Gallery, “Uprooted: The Incarceration of Japanese Americans.” All photographs were drawn from the War Relocation Authority Photographs of Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement, 1942–1945, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, BANC PIC 1967.014–PIC. The oral histories are from the Japanese American Confinement Sites Oral History Project.

Japanese-American Relocation Reviewed

Japanese-American Relocation Reviewed is a multi-interview volume of oral histories from the Earl Warren in California project, dedicated to a discussion of Japanese American incarceration. In “Volume I: Decision and Exodus,” staff of the Justice Department, legal advisors to the US Army, and US and California State attorneys discuss the role of the US Department of Justice and the Western Defense Command in defining and administering policy towards enemy nationals, California Attorney General Earl Warren’s role in the forced removal of Japanese Americans to incarceration camps, the civil defense program, martial law, and the development of a constitutional argument for forced removal.

“We kept saying that we won’t do it and haven’t got the authority to do it. And there are enough precedents, you know with Lincoln suspending the writ of habeas corpus, that if the military wanted to do it, they could do it. But we frankly never thought they would. We thought they were too damn busy getting the troops to go fight a war some place else. That was our mistake.”

—James Rowe, assistant to United States Attorney General Francis Biddle

In “Volume II: The Internment,” members of the War Relocation Authority discuss the authority, selection, and administration of incarceration camp sites; resettlement out of the incarceration camps; origin and activities of the Pacific Coast Committee on American Principles and Fair Play. It also includes an appended interview with a wartime YWCA national board member on Idaho’s Minidoka camp in 1943; an address given by Robert B. Cozzens in 1945, “The Future of America’s Japanese;” and reproductions of Hisako Hibi’s paintings of Tanforan and Topaz.

The Office of Redress Administration Oral History Project

In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, a historic piece of legislation that sought, for the first time, to provide a measure of justice to Japanese Americans forty-six years after their incarceration during World War II. Over its decade-long operation (1988–1998), the Office of Redress Administration reached over 82,000 people with a redress payment and official apology letter from the President of the United States. Redress: An Oral History Project, by Emi Kuboyama, project creator and interviewer, with Todd Holmes, Oral History Center historian and interviewer, documents the complex history of Japanese American redress. The film, Redress, provides the first in-depth look at the historic program as told by both those who administered and participated in it. Additional educational materials supplement the film by providing historical overviews of the Japanese American experience and redress program, as well as a list of resources for further study and discussion. The project received the generous support of the Henri and Tomoye Takahashi Foundation and the National Park Service, US Department of Interior.

The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records and Japanese American Relocation Digital Archive

The Bancroft Library’s documentation of the Japanese American experience during World War II includes thousands of primary source materials drawn from an extensive collection of manuscripts, photographs, as well as audio and video. The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records, accessible through the Online Archive of California, consists of surplus copies of U.S. War Relocation Authority agency documents, including publications, staff papers, reports, correspondences, press releases, newspaper clippings, scrapbooks and a few photographs. Included is the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study, University of California, Berkeley, 1942-1946, containing diaries, letters and staff correspondence, reports and studies. These records include 250.5 linear feet (335 boxes, 84 cartons, 41 oversize volumes (folios), 7 oversize folders, 2 oversize boxes; 380 microfilm reels; 5,660 digital objects) (BANC MSS 67/14 c). The related Finding Aid to the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records 1930-1974 provides additional detail about the collection, including acquisition information, historic notes, scope, and contents.

In addition, Calisphere hosts the Japanese American Relocation Digital Archive (JARDA), which contains thousands of primary sources documenting Japanese American incarceration, including: personal diaries, letters, photographs, and drawings; US War Relocation Authority materials, including newsletters, final reports, photographs, and other documents relating to the day-to-day administration; and personal histories documenting the lives of the people who were incarcerated in the camps, as well as of the administrators who created and worked there. Curated by the University of California, JARDA makes accessible materials from libraries, museums, archives, and oral history programs across California.

Part 2: Related Projects

Rosie the Riveter World War II American Home Front Oral History Project

The Rosie the Riveter World War II American Home Front Oral History Project comprises more than 200 interviews with women and men about the home front experience in the Bay Area. Many of the interviews in these projects include either brief references to or longer discussions about the World War II-era incarceration of Japanese Americans, and cover a broad range of experiences from a multiplicity of perspectives. Some interviews feature individuals who were incarcerated, while other interviews feature Japanese Americans in Hawaii and elsewhere who were not, but who recalled being affected by fear and prejudice. Other interviews include people who were friends, classmates, neighbors, and coworkers, who recalled the forced removal, and the emotions they experienced. Some of these acquaintances were troubled or appalled, whereas others were relieved and thought it justified. Some took care of farms and property until their neighbors returned; others benefited financially. Some go into great detail about race relations in farming and other communities throughout California.

“We used to say, now, why did they make all the Japanese pilots look so ugly?”

—Gladys Okada, in reference to World War II American war films

Volumes about Earl Warren

Two projects, Earl Warren in California and Law Clerks of Earl Warren, center around Earl Warren, who was California’s attorney general (1939–43) and governor (1943–53), before becoming chief justice of the Supreme Court (1953–69), and include an interview with Warren himself. The California project focuses on the years 1925–53, and documents the executive branch, the legislature, criminal justice, and political campaigns; Warren’s life; and changes in California during this period. The California project includes numerous multi-interview volumes that address different issues, including two volumes on labor, exploring Warren from the perspective of union members and labor leaders. The Law Clerks project comprises interviews of more than 40 of Warren’s law clerks; these narrators discuss watershed cases, the evolution of constitutional law, and other issues related to the court. Among other subjects, issues that arose in the interviews in these projects included the ways in which the narrators responded to the executive order; economic, military, and other motivations for the order; the process of identifying individuals and where they lived; reparations; economic consequences; and reflections on Warren’s actions and opinions. Earl Warren himself, in his interview, Conversations with Earl Warren on California Government, briefly addresses the incarceration and aftermath, including enforcement and other issues related to the Alien Land law, preparation of maps documenting where Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans lived, rationale for incarceration, reparations, and return from the camps.

“‘We urge you to appoint immediately a trustee to hold in trust all the properties of the Japanese in this state… lest they be taken over by the wolves.’ They didn’t do anything. All the wolves came in and took over their property.”

—Richard Perrin Graves, executive of the League of California Cities and member of the Ninth Regional Civil Defense Board, on his telegram to the US attorney general

Related Papers

The Bancroft Library and greater UC Berkeley Library have extensive collections that address Japanese American incarceration during World War II and related matters. Here are a few. The complete files of the Fair Play Committee (Pacific Coast Committee on American Principles and Fair Play) are held in the library and include a comprehensive file of newspaper clippings from West Coast publications. The papers of Senator Hiram W. Johnson have information on land laws and Asian immigration. Senator James D. Phelan‘s records document anti-Japanese sentiment in the 1920s. The papers of Robert W. Kenny, who succeeded Earl Warren as attorney general in 1943, have information on law enforcement questions in the aftermath of forced relocation.

Part 3: Individual interviews

“We can’t deny that the black people who lived in the Western Addition moved into places that were vacated because [of] the Japanese Americans who were put into internment camps. Our relationship with Japanese Americans is somehow affected by that history.”

—Carl Anthony, architect and environmental justice activist

Dozens of individual interviews scattered throughout the Oral History Center archive, with people from different backgrounds and walks of life, also detail many facets of this chapter in history. Although they were interviewed about other matters, the narrators in their oral histories in some way addressed Japanese American incarceration — sometimes only in passing, at other times more in depth. Some of the more well-known narrators include the following. Photographers Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange discuss the artistic process, the ownership of their photographs, and the conditions in the camps. Willie Brown, speaker of the California Assembly and mayor of San Francisco, and Carl Anthony, architect and environmental justice activist, address race relations and how some black communities may have benefited from the forced relocation of Japanese Americans. Thomas Chinn, a historian and publisher of the Chinese Digest, discusses the evolution of race relations between Chinese and Japanese Americans in the United States, and noted that after Pearl Harbor, some people in Chinese communities wanted to distinguish themselves in order to avoid the same fate. Japanese American artist Ruth Asawa details her father being taken away by the FBI, her family’s subsequent incarceration, and the role incarceration played in her development as an artist.

“All this equipment my father had gathered — the books, everything that had to do with Japan — they just made a big bonfire and burned all of that. Everybody had panicked at that time. My sister cried and she said, ‘Oh, please don’t, don’t burn the books.’”

— Ruth Asawa, artist, on the fear her family experienced after her father was taken away

The best way to find individual OHC interviews that address any subject is to search by keyword from the search feature on our home page. Use as many keywords as you can think of (one at a time) that might relate to the topic. When you get to the results page, you will see a list of oral histories. Click on any one to get to detailed metadata about that oral history, plus access to the PDF of the oral history itself. As a first step, the abstract provides an overview of the major themes in the oral history. For a more comprehensive look, you can open the oral history directly from this page within digital collections; then use the search feature from within the oral history to find keywords. The oral history will also have a table of contents, and some also have an interview history and other front matter that will provide more information.

Part 4: How to search our collection:

Browse and access all of the oral history projects mentioned in this collection guide from the Oral History Center’s projects page. The projects page will provide a description of the project, and a list of all the oral histories on that project in the UC Library’s digital collections. To search the OHC’s archive by name, keyword, and other criteria, go to the OHC search feature on our home page. The OHC’s guides to various subjects in our collection can be accessed from the collections guide page. If you’re interested in making a documentary, podcast, or in undertaking other creative endeavors, you can access the audio/video and any related photos or ephemera through The Bancroft Library. You will need to open an account to order and access materials in the Reading Room. And here is more information about Rights and Permissions.

Explore collections related to Japanese American incarceration during World War II at all UC campuses by going to the UC Library Search. To explore all holdings from The Bancroft Library, go to the Advanced Search option from the Library Search page, and check “UC Berkeley Special Collections and Archives,” then search by keyword and other criteria.

Part 5: Selected articles that highlight and synthesize this work

The Oral History Center Presents the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project, by Shanna Farrell

The Oral History Center Presents The Berkeley Remix Season 8: “‘From Generation to Generation’: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration” by Amanda Tewes

Graphic Narrative Art by Emily Ehlen from OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, by Roger Eardley-Pryor

Q&A with Artist Emily Ehlen on Illustrating the OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, by Roger Eardley-Pryor

New podcast series explores the legacy of Japanese American incarceration: Read a Q&A with the Oral History Center’s Shanna Farrell about the Project, by UC Berkeley News reporter Anne Brice

‘I knew I had to draw it’: Illustrator brings to life testimonies of Japanese Americans incarcerated during WWII and their descendants in new Oral History Center project, by Dan Vaccaro, writer for UC Library Communications

Interconnections, by Roger Eardley-Pryor

Out of the Archives: Patrick Hayashi: From Mail Carrier to Associate President to Artist, by UC Berkeley undergraduate research apprentice Zachary Matsumoto

OHC URAP Student Zachary Matsumoto Reflects on Work with Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project, by UC Berkeley undergraduate research apprentice Zachary Matsumoto

‘Never again’: Library exhibit tells story of WWII Japanese American incarceration, sounds alarm on importance of remembering by Dan Vaccaro, writer for UC Library Communications

Oral history project highlights the little-known Japanese American redress program, by UC Berkeley News reporter Anne Brice

Redress: A film about the Office of Redress Administration by Edna Horiuchi in Discover Nikkei

Janet Daijogo: Japanese Incarceration and Finding Her Place through Aikido and Teaching, by UC Berkeley undergraduate and Oral History Center research assistant Deborah Qu

Bury the Phonograph: Oral Histories Preserve Records of Life in Hawaii During World War II, by UC Berkeley undergraduate and Oral History Center editorial assistant Shannon White

Part 6: Acknowledgements

National Park Service, Department of Interior

The following projects were funded, in part, by a grant from the US Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the US Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the US Government.

Japanese American Confinement Sites Oral History Project

Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project

Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records

Office of Redress Administration Oral History Project

Henri and Tomoye Takahashi Foundation

The Office of Redress Administration Oral History Project received generous support from the Henri and Tomoye Takahashi Foundation. The foundation also provided generous support for a second phase of interviews for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

About the Oral History Center

UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center, or the OHC, is one of the oldest oral history programs in the world. We produce carefully researched, recorded, and transcribed oral histories and interpretive materials for the widest possible use. Since 1953 we have been preserving voices of people from all walks of life, with varying perspectives, experiences, pursuits, and backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you would like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. The Oral History Center is a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. As such, we must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

Sign up for the Oral History Center’s Advanced Institute (August 5–9)

The UC Berkeley Oral History Center is pleased to announce that applications are open for the 2024 Advanced Institute!

The OHC is offering online versions of our educational programs again this year.

Advanced Institute: M–F, August 5–9, 8:30 a.m.–2 p.m., via Zoom

We are now accepting applications for our 2024 Advanced Institute on a rolling basis. Please apply early, as spots fill quickly.

The Oral History Center is offering a virtual version of our one-week Advanced Institute on the methodology, theory, and practice of oral history. This will take place Aug. 5-9, 2024.

The institute is designed for graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, university faculty, independent scholars, and museum and community-based historians who are engaged in oral history work. The goal of the institute is to strengthen the ability of its participants to conduct research-focused interviews and to consider special characteristics of interviews as historical evidence in a rigorous academic environment.

We ask that applicants have a project in mind that they would like to workshop during the week. All participants are required to attend small daily breakout groups in which they will workshop projects.

In the sessions, we will devote particular attention to how oral history interviews can broaden and deepen historical interpretation situated within contemporary discussions of history, subjectivity, memory, and memoir.

Apply for the Advanced Institute.

Overview of the week

The institute is structured around the life cycle of an interview. Each day will focus on a component of the interview, including foundational aspects of oral history, project conceptualization, the interview itself, analytic and interpretive strategies, and research presentation and dissemination.

Instruction will take place online tentatively from 8:30 a.m. to 2 p.m. Pacific time, with breaks woven in. There will be three sessions a day: two seminar sessions and a workshop. Seminars will cover oral history theory, legal and ethical issues, project planning, oral history and the audience, anatomy of an interview, editing, fundraising, and analysis and presentation. During workshops, participants will work throughout the week in small groups, led by faculty, to develop and refine their projects.

Participants will be provided with a resource packet that includes a reader, contact information, and supplemental resources. These resources will be made available electronically prior to the institute, along with the schedule.

Applications and cost

The cost of the institute is $600. We are offering a limited number of participants a discounted tuition of $300 for students, independent scholars, or those experiencing financial hardship. If you would like to apply for discounted tuition, please indicate this on your application form and we will send you more information.

Please note that the OHC is a soft-money research office of the university, and as such receives precious little state funding. Therefore, it is necessary that this educational initiative be a self-funding program. Unfortunately, we are unable to provide financial assistance to participants other than our limited number of scholarships. We encourage you to check in with your home institutions about financial assistance; in the past we have found that many programs have budgets to help underwrite some of the costs associated with attendance. We will provide receipts and certificates of completion as required for reimbursement.

Applications are accepted on a rolling basis. We encourage you to apply early, as spots fill up quickly.

Questions

Please contact Shanna Farrell (sfarrell@library.berkeley.edu) with any questions.

About the Oral History Center

UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center, or the OHC, is one of the oldest oral history programs in the world. We produce carefully researched, recorded, and transcribed oral histories and interpretive materials for the widest possible use. Since 1953 we have been preserving voices of people from all walks of life, with varying perspectives, experiences, pursuits, and backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public.

Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Sign up for the Oral History Center’s Introductory Workshop (March 8)

The UC Berkeley Oral History Center is pleased to announce that applications are open for the 2024 Introductory Workshop!

The OHC is offering online versions of our educational programs again this year.

Introductory Workshop: Friday, March 8 from 8:30 a.m. to 2:30.p.m. Pacific Time, via Zoom

The 2024 Introduction to Oral History Workshop will be held virtually via Zoom on Friday, March 8, from 8:30 a.m. to 2:30.p.m. Pacific Time, with breaks woven in. Applications are now being accepted on a rolling basis. Please apply early, as spots fill up quickly.

Apply for the Introductory Workshop.

This workshop is designed for people who are interested in an introduction to the basic practice of oral history and in learning best practices. The workshop serves as a companion to our more in-depth Advanced Oral History Summer Institute held in August.

The workshop focuses on the foundational elements of oral history, including methodology and ethics, practice, and recording. It will be taught by our seasoned oral historians and include hands-on practice exercises. Everyone is welcome to attend the workshop. Prior attendees have included community-based historians, teachers, genealogists, public historians, and students in college or graduate school.

Tuition is $150. We are offering a limited number of participants a discounted tuition of $75 for students, independent scholars, or those experiencing financial hardship. If you would like to apply for discounted tuition, please indicate this on your application form and we will send you more information. Please note that the OHC is a soft-money research office of the university, and as such receives precious little state funding. Therefore, it is necessary that this educational initiative be a self-funding program. Unfortunately, we are unable to provide financial assistance to participants other than our limited number of scholarships. We encourage you to check in with your home institutions about financial assistance; in the past we have found that many programs have budgets to help underwrite some of the costs associated with attendance. We will provide receipts and certificates of completion as required for reimbursement.

Applications are accepted on a rolling basis. We encourage you to apply early, as spots fill up quickly.

If you have specific questions, please contact Shanna Farrell (sfarrell@library.berkeley.edu)

About the Oral History Center

UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center, or the OHC, is one of the oldest oral history programs in the world. We produce carefully researched, recorded, and transcribed oral histories and interpretive materials for the widest possible use. Since 1953 we have been preserving voices of people from all walks of life, with varying perspectives, experiences, pursuits, and backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public.

Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Out of the Archives: Patrick Hayashi: From Mail Carrier to Associate President to Artist

by Zachary Matsumoto