What’s New

Art for the Asking: Check-Out Art From The Graphic Arts Loan Collection At The Morrison Library August 26 & 27

The Graphic Arts Loan Collection (GALC) at the Morrison Library has been checking out art to UC Berkeley students, staff, and faculty since 1958 and it is back again this year!

The Graphic Arts Loan Collection (GALC) at the Morrison Library has been checking out art to UC Berkeley students, staff, and faculty since 1958 and it is back again this year!

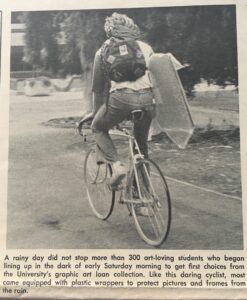

The purpose of the GALC since its inception has been to put art in the hands of UC Berkeley students (and the best way to appreciate art is to live with it!), so on August 26 and 27, from 10am to 4pm, UC Berkeley students can come to the Morrison Library (101 Doe Library) and check-out up to two pieces of art from the GALC’s collection to take home and hang on their walls for the academic year. The prints will be available to students on a first come, first served basis.

The purpose of the GALC since its inception has been to put art in the hands of UC Berkeley students (and the best way to appreciate art is to live with it!), so on August 26 and 27, from 10am to 4pm, UC Berkeley students can come to the Morrison Library (101 Doe Library) and check-out up to two pieces of art from the GALC’s collection to take home and hang on their walls for the academic year. The prints will be available to students on a first come, first served basis.

If you would like to see what we have before you come to the Morrison Library, all the prints are available to browse online at the Graphic Arts Loan Collection website. Not everything in the collection will be available at the Morrison Library these days, but much of the collection will. Please note that the Graphic Arts Loan Collection will not be available to staff and faculty members during this time, but only available to UC Berkeley students. Starting August 29th students can reserve prints from the collection through the GALC website, and on September 9th, faculty and staff can begin reserving prints. Any questions about the GALC can be directed to graphicarts-library@berkeley.edu.

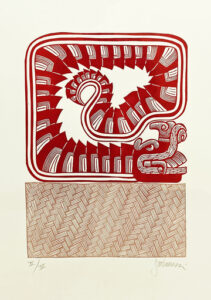

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled: Trees With Mattress Culebra en el Petate, Sergio Sanchez Santamaria Faith Ringgold, Jo Baker’s Birthday

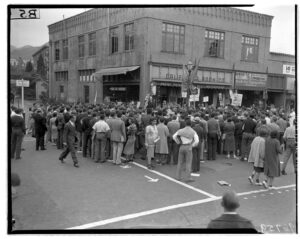

The Bancroft Library’s San Francisco Examiner photograph archive

As part of the UC Berkeley University Library’s ongoing commitment to make all our collections easier to use, reuse, and publish from, we are excited to announce that we have just eliminated licensing hurdles for use of over 5 million photographs taken by San Francisco Examiner staff photographers in our Fang family San Francisco examiner photograph archive negative files, BANC PIC 2006.029–NEG, and Fang family San Francisco examiner photograph archive photographic print files, BANC PIC 2006.029–PIC.

Every photograph within these photographic print and negative collections that were taken by an SF Examiner staff photographer are now licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license (CC BY 4.0). This means that anyone around the world can incorporate these photos into papers, projects, and productions—even commercial ones—without ever getting further permission or another license from us.

What is the San Francisco Examiner collection?

The SF Examiner has been published since 1863, and continues to be one of The City’s daily newspapers. It was acquired by George Hearst in 1880 and given to his son, William Randolph Hearst, in 1887. It was the founding cornerstone of the Hearst media empire, and remained part of the Hearst Corporation’s holdings until it was sold, in 2000, to the Fang family of San Francisco. In 2006 the Examiner’s photo morgue, totaling over 5 million individual images, was donated to The Bancroft Library by the Fang family’s successors, the SF Newspaper Company, LLC.

Along with the gift of negatives and photographic prints, the copyright to all photographs taken by SF Examiner staff photographers was transferred to the UC Regents, to be managed by UC Berkeley Library. However, the copyright to works (mainly in the form of photographic prints) that appear in the collection that were not created by SF Examiner staff was not part of the copyright transfer to the University. Copyright to any works not taken by SF Examiner staff is presumed to rest with the originating agency or photographer. The Library maintains a list of known SF Examiner staff photographers and can assist in making identification of particular photographs until the metadata has been updated.

What has changed about the collection?

Although people did not previously need the UC Regents’ permission (sometimes called a “license”) to make fair uses of our SF Examiner photograph archive, because of the progressive permissions policy we created, prior to January 2024 people did need a license to reuse these works if their intended use exceeded fair use. As a result, hundreds of book publishers, journals, and film-makers sought licenses from the Library each year to publish our Examiner photos.

The UC Berkeley Library recognized this as an unnecessary barrier for research and scholarship, and has now exercised its authority on behalf of the UC Regents to freely license the SF Examiner photographs in our collection that were taken by staff photographers under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license (CC BY 4.0). This license is designed for maximum dissemination and use of the materials.

How to use SF Examiner collection photographs

Now that the photographs by SF Examiner staff photographers have a CC BY license applied to them, no additional permission or license from the UC Regents or anyone else is needed to use these works, even if you are using the work for commercial purposes. No fees will be charged, and no additional paperwork is necessary from us for you to proceed with your use.

Making your usage even easier is the fact that over 22,000 of these negative strips have been digitized and made available via the Library’s Digital Collections Site, and the finding aid for the prints and negatives have more information about the photographs that have not yet been digitized.

The CC BY license does require attribution to the copyright owner, which in this case is the UC Regents. Researchers are asked to attribute use of reproductions subject to this policy as follows, or in accordance with discipline-specific standards:

Fang family San Francisco Examiner photograph archive, © The Regents of the University of California, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. This work is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license.

One final note on usage: While the SF Examiner Collection now carries a CC BY license, this does not mean that other federal or state laws or contractual agreements do not apply to their use and distribution. For instance, there may be sensitive material protected by privacy laws, or intended uses that might fall under state rights of publicity. It is the researcher’s responsibility to assess permissible uses under all other laws and conditions. Please see our Permissions Policy for more information.

Other Library collections with a CC BY license

The Fang family San Francisco Examiner photograph archive joins a number of other collections that the Library has opened under a CC BY license, including the photo morgue of the San Francisco News-Call Bulletin. All of the collections that have had a CC BY license applied can be found on our Easy to Use Collections page.

Happy researching!

Wikiphiliacs, Unite! (At our Wikipedia Editathon, on Valentine’s Day, 2024)

I am a proud Wikiphiliac. At least, according to the Urban Dictionary, which defines Wikiphilia as “a powerful obsession with Wikipedia”. I have many of the signs it warns of, including “accessing Wikipedia several times a day…spending much more time on Wikipedia than originally intended [and]… compulsively switching to other Wikipedia articles, using the hyperlinks within articles, often without obtaining the originally sought information and leaving a bizarre informational “trail” in his/her browsing history” (but that last part is just normal life as a librarian).

How else do I love Wikipedia? Let me count the ways! As a librarian, I always approach crowd-sourced information with a critical eye, but I also admire that Wikipedia has its own standards for fact-checking, and in fact some topics are locked to public editing. It takes its mission very seriously. It also has an accessible and neutral tone. Especially when I want to learn about a technical topic, it can give me a straightforward and helpful way to approach it. I also use it pretty routinely as a way to look at collections of sources about a topic; when I was a medical librarian, I was asked for data on the condition neurofibromatosis, and at that time the best basic links I found were in the references for the Wikipedia article. Last and maybe most importantly, the fact that anyone can edit is a huge strength…with challenges. Wikipedia openly admits its content is skewed by the gender and racial imbalance of its editors, and knowing this is part of approaching it critically, but it also means that IT CAN CHANGE, and WE CAN CHANGE IT.

Given that philia, a word taken from Ancient Greek (according to the philia Wikipedia article), means affection for or love of something, it’s fitting that our 2024 Wikipedia Editathon is part of UC’s Love Data Week, and happens on Valentine’s Day. If you would like to learn to contribute to this amazing resource, and perhaps even help diversify its editorial pool, we can get you started! There isn’t yet a Wikipedia page on Wikiphilia, but maybe you could create one! There already is a podcast series…

If you’re interested in learning more, we warmly welcome you and invite you to join us on Wednesday, February 14, from 1-2:30 for the 2024 UC Berkeley Libraries Wikipedia Editathon. No experience is required—we will teach you all you need to know about editing! (but, if you want to edit with us in real time, please create a Wikipedia account before the workshop—information on how to do that is on the registration page). The link to register is here, and you can contact any of the workshop leaders with questions. We hope you will join us, and we look forward to editing with you!

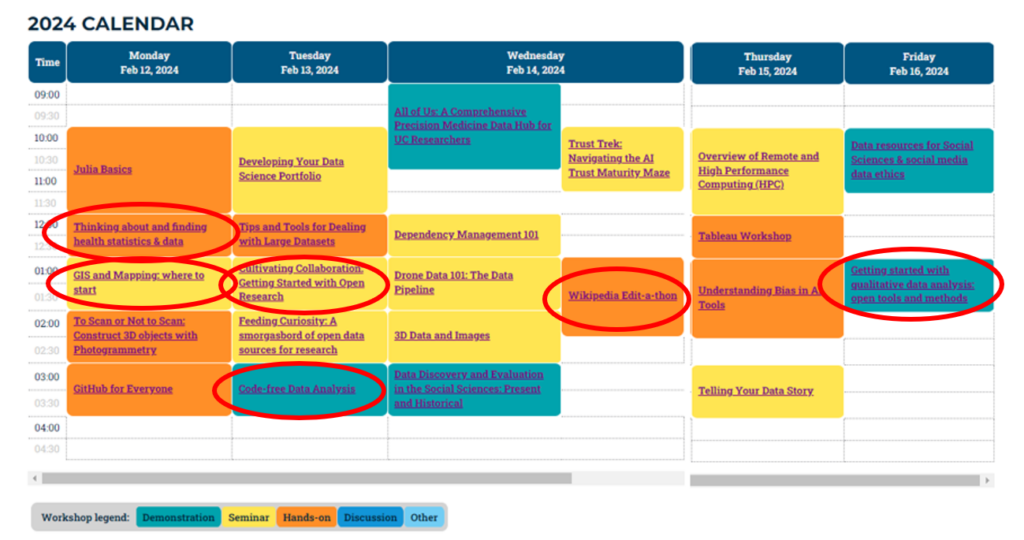

NOTE: the Wikipedia Editathon is just one of the programs that’s part of the University of California’s Love Data Week 2024! Don’t forget to check out all the other great UC Love Data Week offerings—this year UC Berkeley Librarians are hosting/co-hosting SIX different sessions! Here are those UCB-led workshop links, and the full calendar is linked here:

Thinking About and Finding Health Statistics & Data

GIS & Mapping: Where to Start

Cultivating Collaboration: Getting Started with Open Research

Code-free Data Analysis

Wikipedia Edit-a-thon

Getting Started with Qualitative Data Analysis

New Publication from Faculty Julia Bryan-Wilson

The most comprehensive book on the work of Liza Lou, whose popular and critically acclaimed installations made entirely of beads consider the important themes of women, community, and the valorization of labor.

Liza Lou first gained attention in 1996 when her room-sized sculpture Kitchen was shown at the New Museum in New York. Representing five years of individual labor, this groundbreaking work subverted standards of art by introducing glass beads as a fine art material. The project blurred the rigid boundary between fine art and craft, and established Lou’s long-standing exploration of materiality, process, and beauty. Working within a craft métier has led the artist to work in a variety of socially engaged settings, from community groups in Los Angeles, to a collective she founded in Durban, South Africa. Over the past fifteen years, Lou has focused on a poetic approach to abstraction as a way to highlight the process underlying her work.

In this comprehensive volume that considers the entirety of Lou’s singular vision, curators, art historians, and artists offer important perspectives on the breadth of the work.

Podcast episode 3: “Environmental Justice for All” in The Bancroft Gallery exhibit VOICES FOR THE ENVIRONMENT: A CENTURY OF BAY AREA ACTIVISM

Listen to podcast episode 3, “Environmental Justice for All,” or read a written version of this podcast episode below.

Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism is a gallery exhibition in The Bancroft Library that charts the evolution of environmentalism in the San Francisco Bay Area through the voices of activists who advanced their causes throughout the twentieth century—from wilderness preservation, to economic regulation, to environmental justice. The exhibition is free and open to the public Monday through Friday between 10am to 4pm from Oct. 6, 2023 to Nov. 15, 2024, in The Bancroft Library Gallery, located just inside the east entrance of The Bancroft Library. Curated by UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center, this interactive exhibit is the first in-depth effort to showcase oral history along with other archival collections of The Bancroft Library.

This exhibition includes three podcast episodes that offer deeper narratives to supplement the archival posters, pamphlets, postcards, photographs, oral history recordings, and film footage that are also presented in the gallery. Please use headphones when listening to podcasts in The Bancroft Library Gallery.

A written version of podcast episode 3 is included below.

Listen to episode 3: “Environmental Justice for All” on SoundCloud.

PODCAST EPISODE SHOW NOTES:

Episode 3: “Environmental Justice for All.” This podcast episode accompanies a section of the Voices for the Environment exhibition that explores how, in the 1980s and 90s, communities of color in the Bay Area fought against environmental racism by creating new organizations, such as the Urban Habitat Program, to demand environmental justice—the equal treatment and meaningful involvement of all people in environmental decision-making. In the city of Richmond, activists in the West County Toxics Coalition and the Asian Pacific Environmental Network, or APEN, organized against toxic threats from the area’s petrochemical and hazardous waste facilities. Environmental justice activists helped transform the American environmental movement from one focused mostly on landscapes to one that increasingly includes the health and wellbeing of historically disenfranchised people.

This podcast episode features historic interviews from the Oral History Center archives in The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, including segments from oral history interviews with Carl Anthony, Pamela Tau Lee, Henry Clark, and Ahmadia Thomas, all recorded in 1999 and 2000. This episode was narrated by Sasha Khokha, with thanks to KQED Public Radio and The California Report Magazine.

This podcast was produced by Todd Holmes and Roger Eardley-Pryor of the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, with help from Sasha Khokha of KQED. The album and episode images were designed by Gordon Chun.

WRITTEN VERSION OF PODCAST EPISODE 3: “Environmental Justice for All”

Pamela Tau Lee: We cannot be afraid to talk about environmental racism. We cannot be afraid to discuss that, talk about what it means: the discrimination of communities in environmental policy and being left out of the process.

Sasha Khokha: What does justice look like? Whose lives matter? And how does that relate to the environment? In the 1980s and 90s, concerns about toxic industrial waste led communities of color in the Bay Area, and across the nation, to create new organizations and demand environmental justice—the equal treatment and meaningful involvement of all people in environmental decision-making.

Pamela Tau Lee: What we need to deal with is the racism that is the root cause of why industry was targeting communities of color: because communities of color would not have any power; that it’s much more acceptable to dump this stuff in communities of color. So if we shied away from talking about racism, we would then not be able to articulate the realities, and we felt it was racism.

[music]

Sasha Khokha: Welcome to Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism. This podcast accompanies an exhibition in The Bancroft Gallery at UC Berkeley that’s the first major effort to bring together both the oral history and archival collections of The Bancroft Library. The voices you’ll hear were recorded by UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center, founded in 1953 to record and preserve the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world.

Voices for the Environment traces the evolution of environmentalism in the San Francisco Bay Area across the twentieth century, and highlights ways that Bay Area activists have been on the front lines of environmental change.

This is our third and final episode, called “Environmental Justice for All.” I’m your host, Sasha Khokha, from KQED.

[harmonica blues music]

Sasha Khokha: Communities of color have long confronted environmental racism—the disproportionate burden of toxic waste and industrial pollution in neighborhoods that are mostly low income and home to BIPOC folks. But up until the 1980s, the big players in the environmental movement focused on other issues, like preserving redwood groves or protecting bay shoreline from new construction.

Pamela Tau Lee: I think many of the mainstream organizations, you know, they don’t focus on people. They focus on the ecology and other natural resources.

Sasha Khokha: That’s Pamela Tau Lee, a environmental and labor activist from San Francisco whose oral history you’re hearing.

Pamela Tau Lee: These predominantly white organizations did not want to really acknowledge that there was a different experience felt by communities of color.

Sasha Khokha: Take the city of Richmond, where more than 75% of residents identified as people of color in the 2022 census. Located along the bay above Berkeley and Oakland, Richmond has been home to the Chevron oil refinery since 1902. A host of other polluting industries were established there, too. As a result, people in Richmond experience higher levels of pollution and toxins, and have less access to healthy environments to live and play. In the mid-1980s, Richmond residents formed the West County Toxics Coalition. It’s a multi-racial organization aimed at empowering the community to have a greater voice in the environmental issues impacting their neighborhoods.

Henry Clark: You know, like anyone born and raised in North Richmond, we know that there was environmental problems there, you know, over your whole lifetime. So it was quite only logical when the West County Toxics Coalition was formed and they began to organize in North Richmond.

Sasha Khokha: That’s Henry Clark, who grew up in North Richmond. In 1986, after earning his Ph.D. in religious studies, Clark became executive director of the West County Toxics Coalition, and he led it for more than three decades. As a kid in North Richmond, Henry Clark’s home was directly next door to the Chevron oil refinery.

Henry Clark: I can remember clearly waking up many mornings and finding the leaves on the tree burnt crisp overnight from chemical exposure, or you know, going outside and the air would be so foul that you would literally have to grab your nose and try to not breathe the air and go back in the house and wait until it was cleared up. Those type of situations, you know, were a common experience.

Sasha Khokha: Ahmadia Thomas also knows about the foul air in Richmond. She moved there in the mid-1970s and was active in community organizing.

Ahmadia Thomas: Well, then I first came here, I didn’t know, but I used to smell these terrible odors. And I’d say, “What’s that?” And my husband said, “We all smelled it all the time, and we ain’t never made no kick about it.” But they didn’t know what they were smelling. And they were terrible odors: you know ones that smell like sulfur once in a while. Terrible odors out here, after I got out here. When I first came, I didn’t remember smelling all this stuff, but boy, after I was out here a while, I really got environmentally conscious.

Sasha Khokha: Thomas joined the West County Toxics Coalition, too, in part because she was concerned about how Richmond’s industrial pollution was affecting her health—and her neighbors’ health.

Ahmadia Thomas: Like a lot of people had long-term illnesses. Like, these illnesses we don’t know whether they’re short-term or long-term. But if you’ve been affected, say, five years ago and you’re still affected, well now that’s a long term. But, see, a lot of them has been affected. Children, too.

Sasha Khokha: Regular chemical exposures contributed to those illnesses, and so did the periodic accidents, fires, and explosions at the Chevron refinery.

Ahmadia Thomas: And then when they started having the accidents—whoo! There was always a fire or accident. It would be on the TV or in the paper: “There was an accident, but it wasn’t no harm to your health.” And that ain’t true! [laughs] Got to hearing that.

Sasha Khokha: Here’s Henry Clark again.

Henry Clark: You know, these chemical disasters, they do affect people’s lives and people do die from them. You usually don’t hear about the deaths that do occur. You now, they just end up being faceless people whose families may be aware of it, but most of the time you don’t hear about that. Nor do you really even get a good sense of the health impacts, because usually there’s no type of comprehensive health studies that are done or conducted after these disasters.

Sasha Khokha: But the health studies that have been conducted are clear.

Henry Clark: I do know that there’s a 33 percent higher than state average lung cancer rate throughout the Richmond area stretching actually throughout the county, stretching through the industrial corridor.

Sasha Khokha: Here’s Carl Anthony. He’s an architect, a city planner, and a former professor at UC Berkeley.

Carl Anthony: The communities get it. You don’t have to have a Ph.D. to figure out if you have asthma rates five or six times the regional average, it’s clearly symbolic of racism. It is an environmental racism.

Sasha Khokha: With so many other Bay Area groups focused on land, trees, and wildlife, Carl Anthony saw the need for a new organization to deal with the complex urban issues confronting communities of color.

[blues music]

In 1989, Anthony co-founded the Urban Habitat Program to focus on people who lived in cities. He envisioned it would be as multi-racial and multicultural as the Bay Area where he lived. And to better understand the connections between social injustice, economic inequality, and environmental racism, Anthony also helped create a groundbreaking journal, first published on Earth Day in 1990, called Race, Poverty, and the Environment.

Carl Anthony: When we began the Race, Poverty, and the Environment journal, we started looking at these. What is the energy cycle? We began to see that the whole system of extracting energy, distributing it, consuming it, and waste, at every step were huge social issues.

Sasha Khokha: Like the chemical pollution near oil refineries, or the health and safety issues for workers there, or the high cost of energy for low income people: all intertwined social and environmental issues. As executive director of the Urban Habitat Program, Carl Anthony built upon the Bay Area’s progressive and environmental traditions, with a focus on community-led decision making and public investment in historically disenfranchised neighborhoods. But, the more Anthony engaged with issues of environmental justice, the more problems he saw in the ways that mainstream, mostly white American environmental activists understood their own history.

Carl Anthony: There was a deep problem in the myth of the environmental movement, the story of the environmental movement, as having grown out of a certain understanding about the settlement of North America. Put really briefly, the settlement began in New England when the Puritans arrived, and then they found an empty wilderness, and they cleared the forests and built the dams and the towns, and came all the way across the country, and then they looked back and saw how much devastation they had made.

Sasha Khokha: By the start of the 20th century, that environmental devastation inspired the early conservation movement, led by preservationists like John Muir. But for Carl Anthony, this narrative focused too much on wilderness and the conservation of public lands, and not enough on the history of race and American expansion.

Carl Anthony: You know, if you look back a little bit, you say, “Wait a minute, hold it, what’s wrong with this model?” First of all, the North American continent wasn’t empty. There were ten million people here. So where do they fit in this story? And then, millions of people were brought from Africa who worked the land—now it has been eighteen generations—where do they fit in this story? And in particular, from the point of view of the racial issues, the things that were missing in the John Muir model was that this was the end of manifest destiny. It was the end of the frontier wars with the Indians. These were the years when there was rampant racism against Chinese people and against Japanese people in California; the years when Jim Crow was established, and the national parks were set up that were white only.

Sasha Khokha: If the old land-focused narrative of American environmentalism ignored social and racial issues, it also overlooked the urban issues that Carl Anthony was so passionate about.

Carl Anthony: So, the point I’m making about cities is that the environmental movement took off in many ways by saying, “We’re not connected with that whole thing, that mess around the cities. We’re not going to deal with that.” So there was this big hole. But in many ways, the issues that people are complaining about—whether it’s global warming, or whether it’s the squandering of, you know, chopping down the trees, whatever it is—are rooted in the way that we’re living in cities. So I felt that by setting up the Urban Habitat Program, we would then be in the position to be able to say, “This is how we need to think and act in relationship to restoring our cities. Here’s how we’re going to address the environmental issues; here’s how we’re going to address the social justice issues; here’s how we are going to address the economic issues. And because you care so much about biodiversity and energy efficiency and all these things, we would like to invite you to participate with us in doing that.”

[music]

Sasha Khokha: Bay Area activists soon discovered they weren’t alone in the fight for environmental justice. Shortly after starting the Urban Habitat Program, Anthony learned about the Toxic Wastes and Race report published in New York by the United Church of Christ’s Commission on Racial Justice. That analysis showed how government agencies across the nation consistently located toxic waste facilities in communities of color. And when the Church and other groups began to organize a national summit on environmental justice, the Bay Area sent a huge contingent.

Pamela Tau Lee: . . . 1991, in Washington DC, was so powerful to see people of color in this room talking about their struggles for justice in this country. I had not heard anything as dynamic and comprehensive since the Civil Rights [Movement] when I was young.

Sasha Khokha: Pamela Tau Lee, then a labor activist in San Francisco, attended that First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit.

Pamela Tau Lee: When you came into that room, you saw native people from Alaska, the deserts of Nevada, the Shoshone tribe. You saw African Americans who lived in small towns in the middle of Alabama, from the South, New Orleans, with African Americans from Harlem, and Detroit, and South Central Los Angeles. You saw brown people from Puerto Rico, from the border, together with Chicanos from New Mexico and California and farmworkers.

Sasha Khokha: At the summit, leaders of color shared examples of environmental racism from across the country, and they discussed what to do about it.

Pamela Tau Lee: People were there to articulate, what is it that we are experiencing? And what is it that we want? And what it is that we stand for? One is we cannot be afraid to talk about environmental racism. In many of the discussions when we start to talk with the traditional environmentalists, who are mainly white, or the government, they were very afraid of that term. And we said we cannot be afraid to discuss that, talk about what it means: the discrimination of communities in environmental policy and being left out of the process. The mainstream environmentalists, they didn’t want us to say anything about racism. They wanted us to use the word “equity.” And what we need to deal with is the racism that is the root cause of why industry was targeting communities of color: because communities of color would not have any power, that it’s much more acceptable to dump this stuff in communities of color. So if we shied away from talking about racism, we would then not be able to articulate the realities, and we felt it was racism.

Sasha Khokha: As Pamela Tau Lee recalled, activists at the summit also discussed a way forward: demanding justice and taking action.

Pamela Tau Lee: What we wanted industry and the government to use as the criteria for action was the facts: that there is a Superfund site there, that the soil is contaminated, that children are sick, that people have cancer, that the air quality here is bad. And therefore, do something! And what we were coming up against was, you know, “Prove it. Prove that the people are sick. Prove it.” And these communities don’t have the resources to do that. The government and industry knows these people are sick, knows the air quality is bad, knows the soil is contaminated, and should take action. So that was another key component, illustrated very wonderfully in the Principles of Environmental Justice.

Sasha Khokha: The First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit, and the Principles of Environmental Justice created there, reshaped the trajectory of American environmentalism. It inspired a new generation of activists who put people—not just landscapes—within the environmental agenda. For Pamela Tau Lee, attending that 1991 summit motivated her and others to form a new Asian American organization for environmental justice that would work with people here, in the Bay Area.

Pamela Tau Lee: We came back, Asians came back, we talked together, networked together, and after three years, I think, we formed the Asian Pacific Environmental Network [APEN], which has done very powerful work . . . [with] the ability to begin to articulate what environmental justice looks like for the Asian communities in this country.

Sasha Khokha: The Asian Pacific Environmental Network, or APEN, formed in 1993, and its initial work began in Richmond. APEN helped the Laotian immigrant community from Southeast Asia gain a voice in the larger efforts to address the toxic pollution caused by the Chevron refinery and other industrial sites in the city. Today, APEN continues organizing communities for environmental justice throughout the Bay Area.

[music]

By the mid-1990s, the demands of the environmental justice movement reached the White House. On February 11, 1994, President Bill Clinton signed an Executive Order directing federal agencies to “identify and address the disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects of their actions on minority and low-income populations.” Here’s Carl Anthony reflecting on that moment.

Carl Anthony: Well, I think it was, first of all, an incredible achievement. And I can tell you, the ones that did it in the environmental justice movement were virtually uncompromising that the grassroots people have to be at the table. I mean, [they said], “To hell with all these experts and all these consultants and all these people.” They brought the people in who were suffering from the asthma, and respiratory conditions, and from the cancer.

Sasha Khokha: While the executive order didn’t mandate specific actions by law, Pamela Tau Lee thought it was an important benchmark.

Pamela Tau Lee: I think that President Clinton’s order had a very big impact. Many people want to have more, but there is no way that it was going to become law. But that executive order, I think, gave the movement opportunity to advocate the formation of a national environmental justice advisory committee within the EPA. That enabled the White House to call an interagency body to regularly discuss this. And I think that, you know, it’s not like spectacular changes, but I think that it has made a difference.

[music]

Sasha Khokha: By the late 1990s, when most of the oral histories you’ve heard here were recorded, several environmental justice groups had formed in the Bay Area. Like PODER, a Latinx-led group in San Francisco whose name stood for People Organizing to Demand Environmental and Economic Rights. And PUEBLO, which stood for People United for a Better Life in Oakland. And the Silicon Valley Toxics Coalition in the south bay. These activists often supported each other’s efforts. Here’s Henry Clark.

Henry Clark: Here in the Bay Area, there’s different groups in Oakland or San Francisco that do similar type of work. And so when they have public hearings, or protests, demonstrations, or activities, we go and support their works, send people there to support their work. And when we would have activities here in the Richmond area, they send people over to support our work, so building relationships to mutual support.

Sasha Khokha: Working to integrate environmental, social, and economic change for justice is difficult. So activists celebrate their victories, large and small. Like in the year 2000, when APEN’s Asian Youth Advocates and its Laotian Organizing Project in Richmond were able to create community warning systems in multiple languages for when industrial accidents occur. Or in 1997, when the West County Toxics Coalition shut down the Chevron Ortho Chemical Company’s toxic waste incinerator, which had been belching out pollution for decades.

Henry Clark: That campaign was linked to the Chevron Ortho Chemical Company incinerator that had been operating since 19—I believe—67, on a temporary permit. And Chevron was in the process of getting a permit to expand the hazardous waste that was being burned in that incinerator. The West County Toxics Coalition felt that the company should not get a permit to expand their waste burning. In fact, they should actually decrease the waste that was being incinerated. So we organized a campaign to do public education. We received word that Chevron was withdrawing their permit application to expand the incinerator, and that the incinerator was going to be closing down. And so the incinerator has been closed and dismantled as of June of 1997.

[music]

Sasha Khokha: But creating change doesn’t happen quickly. Most of the big, mainstream and mostly white environmental organizations have been slow to expand their activism, their funding, their membership, and their leadership to include BIPOC folks. Even so, since the 1980s and 90s, activists for environmental justice have unequivocally transformed the U.S. Environmental movement from one focused on trees, and landscapes, and sensitive habitats, to one that increasingly includes the health and wellbeing of historically disenfranchised people.

Carl Anthony: What I consider the most important work that I’m involved in is reframing the environmental story.

Sasha Khokha: Here’s Carl Anthony again.

Carl Anthony: There will have to be a much more systematic acknowledgement that environmental and social issues are connected; they are not separate. In my view, that means the environmental justice movement in some fundamental way must become the mainstream of the environmental movement. And I think the environmental movement has had the enormous luxury of being a white movement. But if we’re really serious about changing the dynamics at a global scale, there’s no way that it can keep going as a white movement.

Sasha Khokha: Bay Area environmental justice organizations, like the Urban Habitat Program, have shown a way for activists to build upon their past while still moving forward, together.

Carl Anthony: We kind of represented that model. That yes, you could in fact be advocates of social justice, you could in fact be militant about social justice, and still be an advocate of environmental preservation.

Sasha Khokha: And Bay Area leaders like Henry Clark and Pamela Tau Lee were on the cutting edge of helping the public understand that environmental justice means justice for all.

Henry Clark: When you’re looking at it from an environmental justice perspective, or justice period, the bottom line is that you work out a situation where it will be just for everyone involved, and that’s really what you have to keep the major focus on, especially when you’re trying to deal with situations that have been historically unjust.

Pamela Tau Lee: Many wealthy whites were content for this to be in the back yards of poor communities of color. Well, we were not going to say, “No, we don’t want it. We’re going to put it in rich, white people’s backyards.” That’s not something that we were going to stand for. We were going to always fight for the protection of all, public health of all, the ecology for all.

Sasha Khokha: After all, as our shared world becomes more interconnected, these are issues that affect all of us. Here’s Carl Anthony again.

Carl Anthony: But ultimately, as we get into the twenty-first century, this is the story of how the whole human race is going to address the shadow side of the industrial revolution. It’s not just a Black story. The fact of the matter is that all of us who benefited from the way the industrial revolution had functioned, the gifts that it has given us, are participants in this problem of the shadow side of consumption and waste and all this. Black people just happen to have, you know, kind of an angle or an insight on a piece of this.

[music]

Sasha Khokha: Our relationships with the world around us define who we are. So do the relationships we have with each other. Over the last century, Bay Area activists helped advance our understanding of both of these kinds of relationships—from preserving California’s ancient forests, to regulating economic development, to pushing for the health of communities of color as an environmental issue. Today, the social and environmental challenges we face appear even more daunting than the ones earlier generations had to face. Only by working together and building on lessons from the past can we work toward the solutions we need to thrive in the twenty-first century and become the newest Voices for the Environment.

[music]

You’ve been listening to “Environmental Justice for All,” the third and final episode in the podcast accompanying Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism. It’s an exhibition in The Bancroft Gallery at UC Berkeley that runs from October 2023 through November 2024. This episode featured historic interviews from the Oral History Center archives in The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. It included segments from oral history interviews with: Carl Anthony, Pamela Tau Lee, Henry Clark, and Ahmadia Thomas. To learn more about these interviews and the Oral History Center, visit the website listed in the show notes. This podcast was produced by Todd Holmes and Roger Eardley-Pryor, with help from me, Sasha Khokha. Thanks to KQED Public Radio and The California Report Magazine. I’m your host, Sasha Khokha. Thanks so much for listening!

End of Podcast Episode 3: “Environmental Justice for All”

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. While we receive modest institutional support, we are a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. We must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

Podcast episode 2: “Tides of Conservation” in The Bancroft Gallery exhibit VOICES FOR THE ENVIRONMENT: A CENTURY OF BAY AREA ACTIVISM

Listen to podcast episode 2, “Tides of Conservation,” or read a written version of this podcast episode below.

Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism is a gallery exhibition in The Bancroft Library that charts the evolution of environmentalism in the San Francisco Bay Area through the voices of activists who advanced their causes throughout the twentieth century—from wilderness preservation, to economic regulation, to environmental justice. The exhibition is free and open to the public Monday through Friday between 10am to 4pm from Oct. 6, 2023 to Nov. 15, 2024, in The Bancroft Library Gallery, located just inside the east entrance of The Bancroft Library. Curated by UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center, this interactive exhibit is the first in-depth effort to showcase oral history along with other archival collections of The Bancroft Library.

This exhibition includes three podcast episodes that offer deeper narratives to supplement the archival posters, pamphlets, postcards, photographs, oral history recordings, and film footage that are also presented in the gallery. Please use headphones when listening to podcasts in The Bancroft Library Gallery.

A written version of podcast episode 2 is included below.

Listen to episode 2: “Tides of Conservation” on SoundCloud.

PODCAST EPISODE SHOW NOTES:

Episode 2: “Tides of Conservation.” This podcast episode accompanies a section of the Voices for the Environment exhibition that explores how three women in Berkeley formed the Save San Francisco Bay Association in the early 1960s to resist numerous land-fill projects that would have turned the waters of the San Francisco Bay into land. By 1965, advocacy from this association, later called Save The Bay, led to the creation of the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission, or BCDC, a new California state agency tasked with balancing the conflicting interests between economic development and environmental conservation. BCDC’s work helped bolster a rising tide of conservation that led eventually to similar state regulatory agencies, including the equally historic California Coastal Commission.

This podcast episode features historic interviews from the Oral History Center archives in The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, including segments from oral history interviews with Esther Gulick, Catherine “Kay” Kerr, and Sylvia McLaughlin recorded in 1985; with Joseph Bodovitz and with Melvin B. Lane, both recorded in 1984. This episode was narrated by Sasha Khokha, with thanks to KQED Public Radio and The California Report Magazine.

This podcast was produced by Todd Holmes and Roger Eardley-Pryor of the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, with help from Sasha Khokha of KQED. The album and episode images were designed by Gordon Chun.

WRITTEN VERSION OF PODCAST EPISODE 2: “Tides of Conservation”

Sylvia McLaughlin: And I was totally appalled, reading the [Berkeley] Gazette, of the city manager’s dream to fill over 2,000 acres in front of Berkeley. And this was one of the things that galvanized us into action.

Sasha Khokha: The San Francisco Bay Area is no stranger to development booms. From the Gold Rush to the rise of Silicon Valley, the region ‘s history has been marked by a steady stream of growth and development. In the decades after World War II, new industries and a roaring postwar economy brought millions of people to the Golden State. By 1962, California ranked as the most populated state in the union. State agencies built dams, universities, and a network of freeways matched only in its intricacy by a statewide aqueduct system stretching over 700 miles, north to south. In the Bay Area, this combined boom in both population and development meant space was at a premium, pushing developers to target building on the 1,600 square miles of the bay itself. By the late 1950s, city councils throughout the region considered a host of fill projects that would turn bay waters into habitable land. And that sparked environmentalists to push back.

Melvin B. Lane: Environmentalists should be extremists. They represent an extreme, and the people who are going to make a buck represent the other one. And the decision-maker should sweat it out in the middle.

[music]

Sasha Khokha: Welcome to Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism. This podcast accompanies an exhibition in The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley that’s the first major effort to bring together both the oral history and archival collections of The Bancroft Library. The voices you’re going to hear were recorded by UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center, founded in 1953 to record and preserve the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world.

Voices for the Environment traces the evolution of environmentalism in the San Francisco Bay Area across the twentieth century. It highlights how Bay Area activists have long been on the front lines of environmental change—from efforts to preserve natural spaces in the wake of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, to the midcentury fight for state environmental protections, to demands to address the disproportionate burden of pollution that sickened communities of color around the bay.

You’re listening to the second episode of Voices for the Environment. We’re calling it “Tides of Conservation.” I’m your host, Sasha Khokha, from KQED.

[mid-century jazz music]

In 1961, Oakland Tribune reporter Ed Salzman published an article detailing the number of proposed projects to fill in parts of the San Francisco Bay. What sparked Salzman’s interest was not any one project in particular. But it was a 1959 Army Corp of Engineers map he had stumbled upon while working on another story in Sausalito. On the surface, the government map was a projection of the San Francisco Bay in the year 2000. To Salzman, it was a horrifying glimpse of the reality that awaited Bay Area residents if developers were allowed to keep filling in the Bay. What he saw took his breath away. On the map, the open bay had been reduced to a river. The article, published along with a graphic of the government map, sent shockwaves around the Bay Area, alarming three Berkeley residents: Catherine “Kay” Kerr, Esther Gulick, Sylvia McLaughlin, who talked about seeing that map in an oral history that all three women recorded together in 1985.

Catherine Kerr: There was no denying the fact that the visible destruction of the Bay had been, maybe, of unconscious concern, so that when the Army Corps map appeared in the Oakland Tribune showing that the Bay would end up being a river by 2020 because of all the fill, it was clear to me that this was certainly a possible train of events, and it needed to be stopped.

Sylvia McLaughlin: And I was totally appalled, reading in the [Berkeley] Gazette, of the city manager’s dream to fill over 2,000 acres in front of Berkeley. And this was one of the things that galvanized us into action.

Catherine Kerr: What happened was that the map that came out in the Tribune was brought to my attention. I went to a tea at the Town and Gown Club, and I said to Sylvia, “Did you see that terrible future of the Bay? And Sylvia said, “I certainly did. I think we should do something about it.” About two weeks later, Esther came over. We were sitting in the living room, and it was a beautiful day, and the Bay was very blue. I said to Esther, “I don’t know what’s going to happen to the bay. Did you see the map in the Tribune?” She said, “Yes. Wasn’t it awful?” I said, “Well, do you think you would have time to do something about it?” Esther said, “Well, yes, I think I would.” So I said, “All right, good. There’s three.” I called Sylvia, and we got together, set a date for coffee, and decided how we would start. We decided to start with Berkeley.

Sasha Khokha: The three Berkeley women who started meeting in the spring of 1961 fit squarely within a well-established Bay Area tradition of women environmental activists. They were white, highly educated, and well-connected in local and state political circles. Kay Kerr, the initial organizer of the group, was a Stanford graduate who was regularly active on the Berkeley campus and in city affairs. Her husband, Clark Kerr, was a Berkeley professor and president of the UC system, a position that put Kay in regular contact with the UC Board of Regents, which included the Governor, Lieutenant Governor, and Speaker of the Assembly. Esther Gulick was a Berkeley graduate and wife of Berkeley economics professor, Charles Gulick. She, too, was active in campus and city affairs. Sylvia McLaughlin had graduated from Vassar College and later married Donald McLaughlin, president of a California gold mining company.

These three Berkeley residents bonded over a desire to save the Bay. They read city council plans, consulted with a host of academics on the Berkeley campus, and then called a meeting of the leading environmental organizations in the Bay Area. They were hoping that after they presented their information, the professional conservationists would take charge and spearhead the effort to save the Bay.

Esther Gulick: We had most of the leaders who were very influential in their own organizations.

Catherine Kerr: All of the conservationists that we could think of. The three of us had decided that we were not conservationists and this was a really terrible problem. We were going to tell them about the problem, and then we expected they would carry the ball.

Esther Gulick: We weren’t going to form an organization at all.

Catherine Kerr: We didn’t have any of the expertise. We explained about the Army Corps map. And everything that we could find out was that there were maybe eighty square miles of fill already proposed by various cities around the Bay. And so we said, “This is the problem.” And so, I remember Dave Brower saying. “Well, it’s just exceedingly important, but the Sierra Club is interested in wilderness and in trails.” Then the next guy, Newton Drury, said, “Well, this is very important, but we’re saving the redwoods, and we can’t save the Bay.” And then it went around the room to the point where there was dead silence. So we said, “Well, the Bay is going to go down the drain.” Dave Brower said, “Now there’s only one thing to do: start a new organization, and we’ll give you all our mailing lists.” And they all wished us a great deal of luck when they went out the door. Yes.

Sylvia McLaughlin: They said, “Someone should really do something about this.”

Esther Gulick: It turned out that we were the somebodies.

Sasha Khokha: When the meeting ended, the mission of saving San Francisco Bay stayed in the hands of these three Berkeley women. The new organization they formed that evening in the Berkeley Hills would be known as the Save San Francisco Bay Association. And the environmental groups who felt they couldn’t take on the Bay campaign? They did follow through on the promise to share their mailing lists with Kerr, Gulick, and McLaughlin. Out of the first 700 mailers the three women sent out, they received some 600 pledges of support. Within a month, Save San Francisco Bay had secured a solid membership base. And those members were starting to get vocal in their opposition to Berkeley’s plan to to fill in more than 2,000 acres of Bay shoreline. The expansion would have doubled the size of the university town.

Sylvia McLaughlin: Berkeley had gotten—their plan was at the stage of the planning commission. They were holding hearings, almost the last stage before it got to the city council itself.

Esther Gulick: I think that’s what made the people of Berkeley, when we once got organized and sent letters to about a thousand people in Berkeley to ask them if they were interested in joining Save The Bay and told them some of the things that were going to happen if this went through—like Berkeley being almost twice the size as it now is, with the other half out in the Bay, and there were things like maybe an airport going to be out there, there were going to be storage buildings and that kind of thing—they just couldn’t believe it. You know? They, like us, thought the Bay belonged to us, the Bay belonged to everybody.

Sasha Khokha: Thanks to the new Save San Francisco Bay Association, Berkeley city council meetings were soon inundated with objections to the plan. So were the mailboxes of elected officials.

Sylvia McLaughlin: We felt that numbers were very important. As an example, at the city council meetings we noticed that the people who stood up to represent themselves had no audience. The city council in those days was very polite. But if someone stood up and said they represented an organization of thus-and-so-many members, the city council was more inclined to lean forward and sit on the edge of their chairs and be a bit more responsive. So from those observations, we felt that it was important to get as many members as possible.

Catherine Kerr: I would say that was one of our very first lessons, that if you were going to save the Bay, you had to have the support, and you had to educate the politicians. And the second thing was that you couldn’t educate them or get their support without facts. So we spent a great deal of time on collecting facts and then educating everybody that would listen.

Esther Gulick: Also, the fact that we were getting members was very important. Because they listened to how many members we had and how many letters they got.

Sylvia McLaughlin: Our members were very responsive. We would suggest that they attend critical city council meetings and they would. Sometimes the following city council meeting would be wall to wall with chamber of commerce people. It went back and forth like that.

[music]

Sasha Khokha: Ultimately, the will of Bay Area residents trumped the aspirations of developers. In 1963, the Berkeley city council rescinded the plan to fill in the Bay from the city’s waterfront master plan. It was a big victory for city residents. And it would change Berkeley and the larger Bay forever. But with dozens of fill plans still pending on the dockets of other cities, the three Berkeley activists knew something had to be done in Sacramento to really save the Bay across the region. That opportunity came the following year when Kay Kerr was able to secure a meeting with state Senator Eugene McAteer.

[music]

A San Francisco native, McAteer was a powerhouse in Bay Area politics. He had served on the San Francisco board of supervisors throughout most of the 1950s before heading to the state senate in 1958. He quickly established himself in the legislature. He was close friends with fellow San Franciscan, Governor Edmund “Pat” Brown, and fostered good working relationships with the leadership of both houses. Like most California politicians of that era, McAteer was a builder and supported a range of development and state infrastructure projects, from freeways and universities to dams and other water projects. He also had a calculating eye when it came to climbing the political ladder. And he could tell that the Bay issue was a significant one for the state. He’d seen the legislature stall over the issue before. So, following his meeting with Kay Kerr, he proposed a different tact: a study commission on regulating bay development.

Joseph Bodovitz became one of the planners to lead that study. After an early career as a reporter for the San Francisco Examiner, Bodovitz worked for many years with the San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Association, also called SPUR. In his oral history, he explained how Eugene McAteer’s involvement in the issue of bay regulation was both novel and key to why the plan succeeded

Joseph Bodovitz: I think what people tend to forget now is how unusual it was to have anybody of McAteer’s stature interested in an environmental issue in the sixties. It would be common now, but part of what was intriguing about it at the time was, here was a person who had not been identified with environmental causes at all, part of the establishment in the state senate, suddenly taking up a brand-new and obviously glamorous, important kind of issue. But, here was a big issue brought by conservationists for a couple of years, and here was the legislature not wanting to legislate. There was no consensus that would have let a bill pass. Yet, here was somebody with the power of McAteer able to say, “Well let’s have a study commission.” And McAteer obviously had enough clout with the governor and with both houses to get a relatively simple thing like that through. But as I say, the kind of political novelty of a McAteer being involved in a “do-gooder”, “posy-plucker” issue just made it a different kind of issue. I don’t know what would be a good example, like Ronald Reagan really being serious about protecting redwoods or something.

Sasha Khokha: The study bill that the legislature passed in 1964 gave McAteer’s team four years to develop a plan and show it could work. Their plan focused on three areas. First, a permit process for all proposed development and land use changes on the Bay. Second, a set of standards and criteria to judge the permit applications. Third, the development of an appointment commission that would hold monthly public hearings and decide on the applications. In the end, McAteer’s study group created what became known as the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission, or BCDC.

These were uncharted waters. There was no precedent for this kind of environmental regulation back in 1965. In fact, BCDC was the first regulatory agency of its kind in the nation. For Joe Bodovitz, the chief architect of the Bay commission plan, this meant that the pressure was on and the clock was ticking.

Joseph Bodovitz: And here was the hand we were dealt in 1965: a temporary commission. Which means if you don’t score a touchdown, then the ballgame is over. Right? You don’t go on forever, so you don’t have the luxury of permanence. The goal was, “Let’s do something that will be the basis for successful legislation in 1969, that will both protect the Bay and encourage the kind of shoreline development you want to have. If you’ve shown, over the four years, that people were fairly treated; and that rational, necessary development was encouraged, not discouraged; and that the valuable bay-fill-in parts of the Bay were protected or whatever, you make a case for continuing. And finally, because the people that oppose you are going to be very strong, very well-financed and all, you have to maintain the public support that got the whole thing started. If you lose that, you’ve got nothing. You’ve got a plan and nobody who cares.

[music]

Sasha Khokha: While Bodovitz crafted the Bay plan and served as executive director of the commission’s staff, the operation of BCDC rested in the hands of founding chairman, Melvin B. Lane. Lane was the publisher of Sunset magazine. He fit the balanced approach McAteer and others envisioned for the new regulatory agency. He was a Republican and a successful businessman who could speak with authority to developers and real estate interests. At the same time, he was an environmentalist whose magazine had long celebrated the beauty of California and the West, and the importance of preserving natural lands. As Lane recalls in his oral history, he approached regulating bay development with a handful of basic policy concepts.

Melvin B. Lane: One of them was that, you don’t put something in the Bay that can just as well go on land. The next one was, you don’t put something next to the Bay that can just as well go inland. And that covered an awful lot of things. A house doesn’t have to be in the Bay, a yacht harbor does. [laughs] You know? So, if there’s a choice, okay, the things that are water-related get a priority over these others. Things that the general public can enjoy will get preference over things that just a limited group can enjoy. The things that a limited group of people can enjoy will get a preference over the something that only is for a single person, or a single owner. There are a lot of industries that need to be in the Bay, but if you fill it up with houses and warehouses, you don’t leave room for those things that really have to be there.

Sasha Khokha: Lane talked about how BCDC took a perspective very different from the view of a city council or a developer.

Melvin B. Lane: I think looking at the resource, and what we thought it should be one hundred years from now, took priority over what somebody could do to make a short-term profit. One of the big theories I came out of it with is called “salami logic.” It’s very true, in my opinion, that if you look at a slice, you see something very different than if you look at the whole loaf. If somebody owns a piece of shoreline and some mud flats, and they go to the city council and they say, “Now I just want to fill in a little bit out here to help my building, but I’m going to put a little path around here, and there’s a picnic table. And I’ve got this architect that’s going to put ivy on my building, and I’m going to create fifty jobs, and I’m going to pay you twenty thousand a year in taxes, and on and on. And, I’ve only taken .0007 per cent of the bay.” A city council can’t turn that down. But if you looked at all of the privately-owned shallow parts of San Francisco Bay and said, “Now if this happens to even a large part of it, was that a good idea?” We’d say, “No.” If you looked at that one slice, you’d say, “Yes.” So as planners, we should be looking at the total, but a developer looks at only his thing.

Sasha Khokha: Operating a commission that actually rejected permits for multi-million-dollar developments wasn’t easy. Almost immediately, BCDC found itself squaring off against all kinds of Bay Area business interests.

Melvin B. Lane: At the time BCDC was created there were some firms who were fighting it extremely hard, and they’d fought McAteer all the way through on the legislation. One of those certainly was Leslie Salt.

Sasha Khokha: Leslie Salt Company was the largest landowner on the San Francisco Bay, operating 26,000 acres of salt ponds at the southern tip of the Bay. By the time BCDC was created, however, this company was looking to develop large portions of their property as commercial and residential real estate. BCDC rejected the proposal. And that was a decision that impacted Mel Lane both personally and professionally, since he knew the family that owned Leslie Salt.

Melvin B. Lane: Aug Schilling, the president, was a friend of my family and my wife’s family. And they were a customer of my company. No, how do I say that? They bought things from us [laughs]. Or at least we were trying to sell them both advertising in our magazine, and one of the companies they owned was Spice Islands, and we published a book for Spice Islands. They were our biggest single customer in book publishing for a period of years right in the middle of all this fighting. So anyway, I knew them. They had decided a couple of years before BCDC came into being, that they were going to start making money on their real estate, because they were never going to do it in the salt business. So, they were off on these grandiose plans for filling in all the salt ponds, and therefore were scared to death of BCDC, as they should have been. And so, we did fight and scratch with them, and anything we ever had in Sacramento they were right there.

Sasha Khokha: We don’t know if Aug Schilling thought his company’s permit would get preferential treatment because he knew Mel Lane. But he didn’t hide his disdain for the new agency regulating development in the Bay. After the decision, he referred to BCDC as “a bunch of Fabian socialists.”

BCDC also battled corporate giants, including US Steel and Castle & Cooke, better known by its two subsidiaries, C&H Sugar and Dole. The two companies proposed large fill projects on either side of the historic Ferry Building in downtown San Francisco. US Steel wanted to build an office complex in the harbor that would have included a 550-foot skyscraper, a structure more than twice the size of the Ferry Building’s clock tower. Castle & Cooke’s project was even more ambitious. They had an idea for something called Ferry Port Plaza, a 42-acre fill that would house a hotel and an assortment of restaurants and shops. The footprint of the proposed plaza would have been 30% larger than Alcatraz Island. BCDC rejected both projects. And that sparked a bitter fight not just with the companies, but also their allies in City Hall, including Mayor Joseph Alioto.

Melvin B. Lane: Well, they wanted to put some big office buildings out in the Bay. And we did fight them on that, and everybody else took credit for it. But that U.S. Steel and Castle & Cook big building, we were the ones that stopped those. And they would have had those, because they had the city politics of San Francisco under control, and Alioto was right in the middle of it. We had awful fights with Joe Alioto over them.

Sasha Khokha: One of the more audacious proposals BCDC faced in its early years, was called the West Bay Project. It was backed by a real estate consortium that included David Rockefeller, Crocker Land company, and Ideal Cement. They wanted to fill in part of the Eastside of the Peninsula running from San Bruno to the San Mateo Bridge. Mel Lane recalls how the plan sought to remove 250 million cubic yards of dirt from San Bruno Mountain to fill in 27 square miles of the Bay.

Melvin B. Lane: They would cut down the mountain, push it in the Bay, and go right over Bayshore [Freeway] onto barges and take it down and fill in down there. And then, Rockefeller would put up the money and all the professional skills of planning the land and marketing it. Well, it’s like Candlestick Park, pushing land into the Bay. Developers just love that, God, they think that is so wonderful. Anyway, we finally wore them down, but they were tough and very able.

[music]

Sasha Khokha: In 1969, the California Legislature made BCDC, or San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission, permanent. Sadly, Senator Eugene McAteer did not live to see the final vote. He suffered a fatal heart attack two years earlier. His vision, however—and the bold activism of people like Kay Kerr, Esther Gulick, and Sylvia McLaughlin—became enshrined in a regulatory agency that was the first of its kind in the country.

BCDC becoming an official state agency marked two milestones in the evolution of Bay Area environmentalism. First, it gave environmental considerations a permanent place in state government. Second, the agency aimed to strike a balance between economic development and environmental conservation. Here’s Joe Bodovitz:

Joseph Bodovitz: But see, it worked both ways, because the more development-minded people had to take a look at marshlands, but similarly, the dyed—absolute, if that’s the right term, conservationists, had to understand there was an economy in the Bay Area, and that shipping, after all, did depend on ports, and ports did depend on dredging and deep water access. People sort of had to confront the legitimate interests of both conservation and development. The idea, again, that Mel felt very strongly about is that reasonable, fair-minded people, confronted with facts in a reasonably unemotional way, are going to come out largely agreeing to the same kinds of things. They may disagree on a particular permit or a particular issue, but no fair-minded person can say marshlands aren’t important. Similarly, no fair-minded person can say ports aren’t important to the Bay Area economy.

Sasha Khokha: In fact, in his oral history, Mel Lane talked about exactly this: how what made BCDC historic was its role as government mediator. It created and enforced rules across the Bay; and it occupied a middle ground between activists and developers. Mel Lane said that was core to its mission.

Melvin B. Lane: I have a theory I inherited from Dave Brower actually. And that is, that environmentalists should be extremists. They represent an extreme, and the people who are going to make a buck represent the other one, and the decision-maker should sweat it out in the middle. These battles are ones that you don’t solve them ever, with the coast or bay or air or water or whatever it is, because tomorrow there is another group of citizens and voters and government leaders, so those battles just go on forever.

[music]

Sasha Khokha: What began with the activism of three women in Berkeley, and a brave proposal from a state senator, flourished into an environmental agency whose impact would be felt for decades to come. The work of BCDC certainly saved San Francisco Bay. It also helped bolster a rising tide of conservation that, in time, led to the creation of similar state regulatory agencies, like the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency, the Delta Stewardship Council, and the equally historic California Coastal Commission, which both Joe Bodovitz and Mel Lane would also help steer in its formative years.

Yet, as the 20th century continued, the Bay Area once again found itself at a crossroads. Yes, environmental concerns now had a permanent place in government, but not everyone received equal treatment. Our next episode of Voices for the Environment explores how the disproportionate impact of pollution on communities of color led to calls for environmental justice.

You’ve been listening to “Tides of Conservation,” the second episode in the podcast for Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism. It’s an exhibition in The Bancroft Gallery at UC Berkeley that runs from October 2023 through November 2024. This segment featured historic interviews from the Oral History Center archives in The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. Interviews include Esther Gulick, Catherine “Kay’ Kerr, Sylvia McLaughlin, Joseph Bodovitz and Melvin B. Lane. To learn more about these interviews and the Oral History Center, visit the website listed in the show notes. This podcast was produced by Todd Holmes and Roger Eardley-Pryor, with help from me, Sasha Khokha. Thanks to KQED Public Radio and The California Report Magazine. I’m your host, Sasha Khokha. Thanks for listening!

End of Podcast Episode 2: “Tides of Conservation.”

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. While we receive modest institutional support, we are a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. We must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including for each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

Podcast episode 1: “A Preservationist Spirit” in The Bancroft Gallery exhibit VOICES FOR THE ENVIRONMENT: A CENTURY OF BAY AREA ACTIVISM

Listen to podcast episode 1, “A Preservationist Spirit,” or read a written version of this podcast episode below.

Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism is a gallery exhibition in The Bancroft Library that charts the evolution of environmentalism in the San Francisco Bay Area through the voices of activists who advanced their causes throughout the twentieth century—from wilderness preservation, to economic regulation, to environmental justice. The exhibition is free and open to the public Monday through Friday between 10am to 4pm from Oct. 6, 2023 to Nov. 15, 2024, in The Bancroft Library Gallery, located just inside the east entrance of The Bancroft Library. Curated by UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center, this interactive exhibit is the first in-depth effort to showcase oral history along with other archival collections of The Bancroft Library.

This exhibition includes three podcast episodes that offer deeper narratives to supplement the archival posters, pamphlets, postcards, photographs, oral history recordings, and film footage that are also presented in the gallery. Please use headphones when listening to podcasts in The Bancroft Library Gallery.

A written version of podcast episode 1 is included below.

Listen to episode 1: “A Preservationist Spirit” on SoundCloud.

PODCAST EPISODE SHOW NOTES:

Episode 1: “A Preservationist Spirit.” This podcast episode accompanies a section of the Voices for the Environment exhibition that explores how, after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, demands to rebuild San Francisco targeted the state’s ancient and fire-resistant redwood trees, while desires for a reliable water supply called for damming the Hetch Hetchy Valley within Yosemite National Park. In the decades that followed, an outpouring of activism shaped the ensuing conflict between economic development and environmental protection, and fueled a preservationist spirit in the Bay Area that would only grow over the century.

This podcast episode features historic interviews from the Oral History Center archives in The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, including segments from the “Growing Up in the Cities” collection recorded in the late 1970s by Frederick M. Wirt, as well as oral history interviews with Carolyn Merchant recorded in 2022, with Ansel Adams recorded in the mid-1970s, and with David Brower recorded in the mid-1970s. The oral history of William E. Colby from 1953 was voiced by Anders Hauge, and the oral history of Francis Farquhar from 1958 was voiced by Ross Bradford. This episode also features audio from the film Two Yosemites, directed and narrated by David Brower in 1955. This episode was narrated by Sasha Khokha of KQED Public Radio and The California Report Magazine.

This podcast was produced by Todd Holmes and Roger Eardley-Pryor of the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, with help from Sasha Khokha of KQED. The album and episode images were designed by Gordon Chun.

WRITTEN VERSION OF PODCAST EPISODE 1: “A Preservationist Spirit”

Anonymous Witness 1: The older people were running around wild! They thought it was the end of the world. Everything was shaking.

Anonymous Witness 2: Kind of a low roar. You had the feeling that the roof was coming off.

Anonymous Witness 3: It was a six-story brick building. We were on the third floor. When we finally got out of the building, we were on the top floor. The top three had gone off.

Anonymous Witness 2: By night the city was—it looked like the whole downtown area was on fire

Anonymous Witness 1: Everything was burned, you couldn’t—the home was gone. Everything was gone.

Sasha Khokha: Those are voices of people who survived the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire. And they’re just some of the rare recordings you’re going to hear in Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism.

[music]

This podcast accompanies an exhibition in The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley that’s the first major effort to bring together both the oral history and archival collections of The Bancroft Library. You’re about to hear more voices recorded by UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center, founded in 1953 to record and preserve the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world.

Voices for the Environment traces the evolution of environmentalism in the San Francisco Bay Area across the twentieth century, and highlights how Bay Area activists have long been on the front lines of environmental change—starting with efforts to preserve natural spaces in the wake of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire. We’ll also learn about the midcentury fight for state environmental protections, and demands to address the disproportionate burden of pollution that sickened communities of color across the Bay.

You’re listening to the first episode of Voices for the Environment. We’re calling it “A Preservationist Spirit.” I’m your host, Sasha Khokha, from KQED.

[music]

Sasha Khokha: A beautiful vista, an ancient forest, a flooded valley. Our relationships with the world around us define who we are, from the air and water that sustains us, to the natural spaces we enjoy, to the creatures we share our surroundings with. Together, we refer to these intertwined elements as “the environment.” Sometimes we struggle with how to change those relationships. We call that work “environmentalism.”

[piano music from the early twentieth century]

In the San Francisco Bay Area, a new environmental spirit was flourishing in the first decade of the twentieth century. The catalyst for this public activism was not pollution, oil spills, or climate change. Not yet. Back then, it was the 1906 earthquake and fire.