Bancroft Library

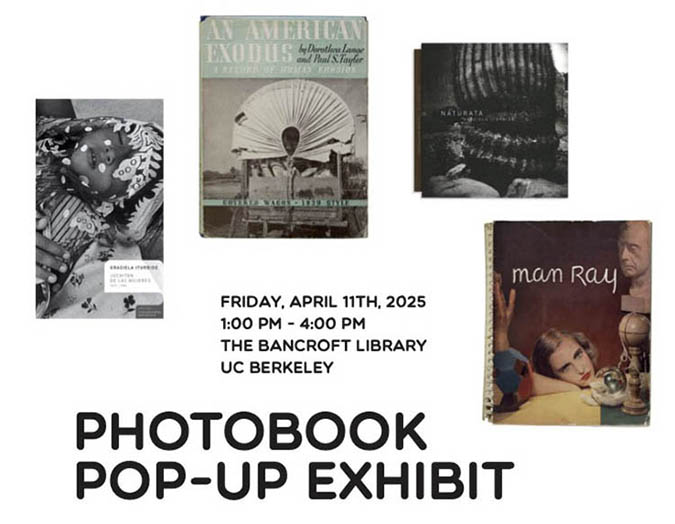

Photobook Pop-Up Exhibit, Friday, April 11

In association with the Reva and David Logan Photobook Symposium at the School of Journalism, the Bancroft Library is hosting a Photobook Pop-Up Exhibit, featuring selections from the Reva and David Logan Photobook Collection (The Bancroft), and photobook gifts from donor Richard Sun (Art History/Classics Library).

Artists featured:

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Claude Cahun, Robert Frank, Dorthea Lange, Miyako Ishiuchi, Graciela Iturbide, Dayanita Singh, Alfred Stieglitz, Francesca Woodman and many more.

Women Faculty at UC Berkeley: Oral Histories of Excellence

By Natalie Naylor

Natalie Naylor is a fourth-year undergraduate studying English and Creative Writing. She has worked as a student editor for the Bancroft Library’s Oral History Center since July 2024 and also wrote “Berkeley SLATE-d for Back to School: Student Community in the Sixties.”

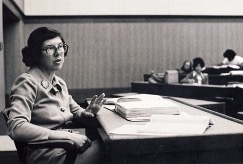

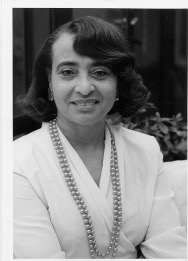

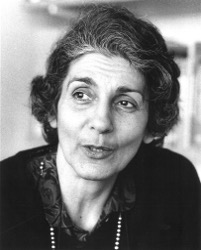

In 1870, the Regents of the University of California system voted to admit women on the same basis as men. Since then, female members of the faculty, staff, and student body have been inextricable from the University of California’s achievements and legacy. This Women’s History Month, the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library would like to highlight interviews from female faculty members who achieved historic “firsts” at the University of California, Berkeley. The four Professors featured in this blog post were interviewed as a part of the Oral History Center’s Education and University of California, African American Faculty and Senior Administrators at Berkeley, and Women Political Leaders projects.

Herma Hill Kay was the second woman ever hired to UC Berkeley’s Law faculty in 1960, following the impending retirement of their first female professor, Barbara Armstrong. Kay taught at Berkeley Law for an astonishing fifty-seven years, during which the number of female faculty and students greatly increased as a direct result of her efforts. Germaine LaBerge, the interviewer for Kay’s oral history, recalls “Only fourteen women anywhere in the United States had become law professors before Professor Kay joined the faculty at Boalt Hall [now Berkeley Law].” In addition to her historic tenure, when Kay was “selected as Boalt’s first woman dean in 1992, she was adding to a long list of ‘firsts’ that, taken together, make an exceptional story” (pg. i).

Kay devoted her career to furthering the rights of women, specifically pursuing cases concerning sex-based discrimination and California marital property laws. As a result, Kay contributed to the conception of the first no-fault divorce law in the United States. In her oral history, she attributed her passion for women’s rights to a firm belief in legal equality for all: “I’ve always felt very strongly—and this came from my father—that women ought to be free and conscious actors. They ought to determine their own role in this world. So I was very opposed to anything that would stand in the way of their self-realization. I feel the same way about racial equality. There shouldn’t be any barriers placed in front of anybody to do what that person wants to do and is able to do.” (Kay 2005, pg. 76) In addition to her academic achievements, Kay played a pivotal role in forming both the Berkeley Faculty Women’s Club in 1969 and the Boalt Hall’s Women’s Association. She passed away at the age of eighty-two in 2017, but her legacy and impact on the law community at UC Berkeley remains evident to this day.

Jewelle Taylor Gibbs began teaching at the UC Berkeley School of Social Welfare in 1979 and earned tenure as a full professor in 1986. Shortly after, in 1993, Gibbs earned an endowed appointment as the Zellerbach Family Fund Professor of Social Policy, Community Change and Practice—a position she held until her retirement in 2000. She became the first African American professor appointed to the position of endowed chair across the UC system. The Oral History Center interviewed Gibbs in 2003 and 2004 as a part of their African American Faculty and Senior Staff Oral History Project. Over the course of her career at the University, she contributed to several key dialogues in African American Studies. These included articles and books she wrote on “minority mental health, young Black men in America, and the O.J. Simpson and Rodney King cases” (pg. v). Gibbs also testified before the U.S. Congress concerning her research on young Black males.

Gibbs devoted her scholarly and personal pursuits to furthering justice and equality for several minority groups, which she detailed during her oral history: “So, this whole idea of all of the early influences which were around social justice from my family, my father and growing up in the church, have kind of really been a very, very deep influence on me in my work, coming back to that and looking at it in the last book that I did and even now things that I’m doing, the kinds of things I’m going to volunteer doing, it’s really coming back to civil rights, human rights, and women’s rights and how we can make our communities work better for minorities, poor people, the disadvantaged people and women. And that’s what I have done” (Gibbs 2010, pg. 424). Upon her retirement in late 2000, Gibbs earned the Berkeley Citation, the University’s highest honor awarded to individuals “whose contributions to UC Berkeley go beyond the call of duty and whose achievements exceed the standards of excellence in their fields.”

As the first woman tenured by the UC Berkeley Anthropology department, Laura Nader had an extensive impact on the University’s history and culture. She joined the faculty in 1960, the same year Herma Hill Kay started at Berkeley Law. Nader published ten books and around 290 other publications over the course of her career. As an influential and popular professor at UC Berkeley, she taught thousands of undergraduate students and supervised more than one-hundred PhD students. She recounted one of these popular classes in her oral history interview: “I puzzled because I never really understood why do students love the course Controlling Processes so much? Why do they remember it? Like the woman who said, ‘I took a course from you ten years ago.’ And I said, ‘You remember it?’ And she said, ‘Yes, it was Controlling Processes.’ Why do they remember it? They don’t remember any courses from one semester to another; who taught it and whatever it is. Their memories are worse than seventy-five year olds. So it opens their eyes to something. But why are our eyes closed? We’re not looking at reality in this country and many people are saying this now.” (Nader 2014, pg. 88)

Nader also taught at several other prestigious universities across the country, such as Yale Law, Harvard Law, and Stanford. Her research explored the interactions of law, anthropology, and energy science, specifically in indigenous Mexican cultures and the Middle East. Nader served as an ambassador for both the UC Berkeley community and the field of anthropology more broadly. As a result of her contributions to law and anthropology, she received the Law and Society Association’s 1995 Kalven prize for distinguished research. Experts across disciplines have commended her theoretical and ethical approaches to her research questions.

In the fall of 1976, Gloria Bowles taught the first cohort of students in the Women’s Studies department at UC Berkeley and served as its founding coordinator. She taught throughout the University of California system at UC Berkeley, UC Santa Cruz, and UC Davis for much of her career as a professor in Comparative Literature and Women’s Studies. She recalled, “In a sense, the women’s movement came to me through my students, because in one of those proposal meetings, they accepted my proposal for Comp Lit 40A, the undergraduate course. I had a wonderful group of women. Of course, these women were so excited to be reading women writers.” (Bowles 2021, page 16)

Bowles, like the other professors highlighted in this blog post, considered the Women’s Liberation Movement in conjunction with other Civil Rights movements taking place during the 20th century. “Feminist was not a word we used when we were undergraduates in Ann Arbor. I think we were more obsessed with civil rights. The women’s movement followed civil rights, and the Women’s Studies Program followed Ethnic Studies, and one movement came and another. I think probably thinking about civil rights causes you to think about your rights, or lack thereof—and of course, totally different, depending on your class and color. I think that I always thought about things like that, although I didn’t give them labels.” (Bowles 2021, page 17)

After her retirement from academia. Bowles established the Berkeley Women’s Studies Movement Archive at UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library. Bowles influenced the Bay Area’s feminist culture and paved the way for generations of female scholars to come.

Conclusion

Herma Hill Kay, Jewelle Taylor Gibbs, Laura Nader, and Gloria Bowles all achieved historic milestones and paved the way for future generations of female students and faculty at UC Berkeley. Without their contributions, UC Berkeley would be drastically different from the community we know today. They are just four of the dozens of influential women faculty members that the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library has interviewed. To find more fascinating oral histories like these, explore the Education and University of California and African American Faculty and Senior Administrators at Berkeley oral history projects. For additional information, explore the 150 Years of Women at Berkeley history project, which includes Oral Histories of Berkeley Women.

Read the full oral histories of these women:

Herma Hill Kay, “Herma Hill Kay: Professor, 1960-Present, and Dean, 1992-2000, Boalt Hall School of Law, UC Berkeley,” interview by Germaine LaBerge in 2003, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2005.

Jewelle Taylor Gibbs, “Jewelle Taylor Gibbs,” interview by Leah McGarrigle in 2002, 2003 and 2004, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2010.

Laura Nader, “Laura Nader: A Life of Teaching, Investigation, Scholarship and Scope,” interview by Samuel Redman and Lisa Rubens in 2013, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2014.

Gloria Bowles, “Gloria Bowles: The Founding of Women’s Studies,” conducted by Amanda Tewes in 2021, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2021.

Additional Sources:

“Berkeley Citation | Berkeley Awards.” 2025. Berkeley.edu. 2025. https://awards.berkeley.edu/university-awards/berkeley-citation/.

“Iconic Professor and Former Berkeley Law Dean Herma Hill Kay Dies at 82.” 2022. UC Berkeley Law. March 24, 2022. https://www.law.berkeley.edu/article/iconic-professor-former-berkeley-law-dean-herma-hill-kay-dies-82/.

“Laura Nader | Anthropology.” Anthropology.berkeley.edu, anthropology.berkeley.edu/laura-nader.

“‘Something Has to Change’: Collection Explores Movement behind UC Berkeley’s Women’s Studies Program.” 2021. UC Berkeley Library. 2021. https://www.lib.berkeley.edu/about/news/womens-studies.

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. As a soft-money research unit of The Bancroft Library, the Oral History Center must raise outside funding to cover its operational costs for conducting, processing, and preserving its oral history work, including the salaries of its interviewers and staff, which are not covered by the university. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

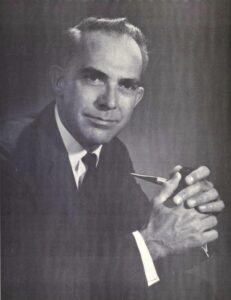

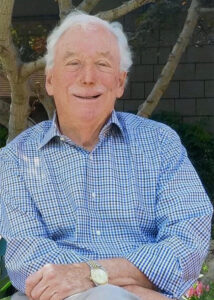

george a. miller (1936-2025)

We are sad to announce the passing of george miller (his preference for lower-case spelling).

George entered the world of The Bancroft Library in 1997, shortly after his retirement and originally as a volunteer helping to process the records in the history of water rights and engineering in California. George had had a storied career in finance, bearing witness to and shaping some of the key developments in the US finance industry in the last half of the twentieth century. Most notable was his idea of passive investment in the form of an index fund, which would track a basket of top-performing stocks, premised on the notion that the growth of the market over time would beat active money managers. While at Bancroft, George also became captivated by the collection of oral histories produced by the Oral History Center. Over time, he began to make contributions to the archive by sponsoring oral histories with key figures in Bay Area politics, environmental activism, and journalism.

It was through this engagement with oral history that my predecessor Martin Meeker eventually persuaded George to do his own oral history. An important theme of George’s oral history is his philanthropic calling, which he described as “graduating from his day job … to more productive things.” A great feature of a life history is that one gets a sense of when values or passions took root. Early on, George developed a sense of duty, which led to a distinguished vocation as a philanthropist to institutions and causes dear to him, repaying the opportunities he was given, not just to his almae matres, UPenn and Cal, but to his community, to young students, to his city, his state, and to the world.

George was known for the pithy sayings that his friends and family called GAMOs – “george a. miller observations.” Underlying many of them was a pragmatic outlook on life, for example, “time is like money; you can only spend it once.” He took one of his father’s aphorisms to heart throughout his life as well, “There’s nothing sadder than something done well that shouldn’t be done at all.” Taking great care to identify what was worth fighting for, he was humble about his ability to bring about change. Musing on this, he proposed his own obituary: “He lived. He cared. He tried. Then he gave up.” But this is someone who spent thirty-five years finding a way to derive steady revenue from the chaos of the market. He invested where he thought he could have an impact. He cared and tried enough to build a credit union in Vietnam from the ground up to 160,000 members, fund the education of hundreds of students at UC Berkeley, make improvements to small-claims courts across the country, support environmental organizations, help revive the Market Street Railway, and secure the future of a beloved bar and grill in San Francisco, to name just a few of his accomplishments.

His friends called George “a piece of work.” He made a cheeky, no-nonsense difference in the world, a difference that we at The Bancroft Library and the Oral History Center have felt deeply and will miss.

Nuclear Complexity and Oral History: Brianna Iswono’s Undergraduate Research, Fall 2024

by Brianna Iswono

Brianna Iswono is a third-year undergraduate student at UC Berkeley majoring in chemical engineering. Throughout the Fall 2024 semester, Brianna worked with Roger Eardley-Pryor of the Oral History Center to earn academic credits through Berkeley’s Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program (URAP). URAP provides opportunities for undergraduates to work closely with Berkeley scholars on cutting edge research projects for which Berkeley is world-renowned. In this post, Brianna reflects on her research about nuclear power as it appeared in the Oral History Center archives.

As a chemical engineering student at UC Berkeley, my coursework only briefly touches on topics of nuclear power and energy. I wanted to learn more and my curiosity deepened as I saw more and more headlines about nuclear energy in news articles and social media. To dive deeper, in the fall of 2024 I joined Berkeley’s URAP (Undergraduate Research Apprenticeship Program) under the mentorship of historian Roger Eardley-Pryor at the Oral History Center, where I analyzed various oral histories and technical reports about nuclear energy. Through this experience, what I discovered was not only a stronger interest in nuclear power, but a field marked by polarizing perspectives and profound complexity—one where simple answers do not exist.

Nuclear power stands as one of the most reliable carbon-free energy sources available today. Unlike fossil fuels, it produces no carbon dioxide during electricity generation, which makes nuclear power a critical tool in the fight against climate change and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Given the growing urgency for energy facilities to reduce their overall emissions, nuclear power offers a viable option for large-scale, reliable energy production. As former Sierra Club president, mountaineer, biophysicist, and Berkeley Lab energy analyst William E. Siri noted in his oral history in the late 1970s, “Coal is a very dirty fuel… That leaves nuclear as one clean energy source until solar and other energy sources are fully developed.” Today, solar and wind are more developed, but the energy they generate drops when the sun sets or when winds cease. By providing steady, continuous power, nuclear energy complements intermittent renewable sources like wind and solar, ensuring grid stability. This reliability reduces the need for fossil fuel-based backup systems and thus helps mitigate climate change.

However, nuclear power is not without its environmental challenges. The construction and operation of plants can disrupt local ecosystems, particularly since they are often built in rural areas rich in biodiversity and ecological value. Habitat disruption, deforestation, and the high demand for water used in reactor cooling all remain significant concerns. The presence of nuclear plants places an increased strain on local water resources, particularly in underserved regions already facing water scarcity. In the first of his two archived oral history interviews, David Brower, the former executive director of the Sierra Club, the nation’s largest environmental organization, explained about the Club’s consideration of nuclear power, “You certainly haven’t helped the poor by degrading the environment, the working place, by not getting into the battles to protect them from the chemicals that they’re exposed to.”

Also, the visual impact of large nuclear facilities can dramatically alter the character of scenic areas. At least in California, public opposition was fueled historically by concern that industrial structures for nuclear power detracts from the natural beauty and environment of rural areas, making them appear stark and out of place. Laurence I. Moss, former Sierra Club president and nuclear engineer, worked directly on construction of nuclear reactors. Moss shared in his oral history, “In my mind it was always a location issue. That was not the right place to put a nuclear power plant, or any industrial facility. I would not want to put a residential development there, anything that would alter the natural environment for the worse.” Moss’s perspective highlights the tension between technological advancement and environmental preservation, underscoring the importance of careful site selection to balance progress with respect for natural landscapes.

Another major challenge, and perhaps the most pressing, is the management of nuclear waste. Nuclear reactors generate long-lived radioactive waste that requires secure, long-term storage, and even the most advanced waste repositories carry the risk of leakage or contamination over the thousands of years that spent nuclear fuel remains toxic. Efforts to manage nuclear waste have included ambitious ideas such as deep-sea disposal or even launching the waste into the sun. However, these approaches fail to fully eliminate the risk of leakage, especially given the exceptionally long timescales over which the waste must remain secure, and they often introduce additional challenges. As Thomas H. Pigford, the founding chair of UC Berkeley’s Department of Nuclear Engineering, explained in his oral history from the late 1990s,“Another more attractive approach is to shoot the radioactive waste into the sun, which would require concentrating it to reduce the weight. And that’s where it belongs, because the sun is so radioactive. But there, the technical challenge or problem is the abort rate of missiles, of space vessels, and so when consulting the people in NASA, we concluded that that was just untenable.” Such unresolved issues remain a central concern for environmental advocates, highlighting the ongoing tension between the potential of nuclear power as a clean energy source and the ecological risks it poses.

Economically, nuclear power presents both opportunities and challenges. Once operational, nuclear reactors have relatively low fuel and operating costs compared to many other energy sources. Uranium, the main fuel used, is highly energy-dense, requiring only small amounts to generate large quantities of energy. This efficiency makes nuclear power a cost-effective solution to meet large-scale energy demands, providing a reliable supply of energy at a lower long-term cost while still delivering the high output needed to sustain industrial and societal needs. After working directly with the economic analysis of nuclear plant construction in the 1960s, Moss shared, “we were able to show that other alternatives, specifically a nuclear power alternative, built in those years could provide power at lower cost than the dams.” Nuclear power also has an extensive reach that goes far beyond reactors, influencing a wide range of industries and technologies. The advancements and expertise gained through working with radiation and the advanced technologies required for waste facilities have helped with the development of new medical technologies used to measure radiation. Professor Pigford was directly involved in establishing the nuclear engineering curriculum at Berkeley and saw its expansion into related medical technologies. In his oral history, Pigford shared “Yes, well, there are plenty of jobs in waste disposal. And they are emphasizing more and more the interaction with the bioengineering program, which, as you probably know, is a new push on the campus. There’s a new department, and they’ve even gone into the field of tomography, which is doing scans on the brain and on the rest of the body. These involve nuclear reactions and so the development of instrumentation for that, techniques of sensing the nuclear radiations and interpreting them, is occupying more and more time.” Pigford’s insight highlights how nuclear engineering graduates have the opportunity to apply their expertise to innovations in health-related technologies, such as medical imaging.

Yet, a major economic challenge of nuclear power is the huge initial investment needed to build a plant. Designing, constructing, and meeting regulatory standards for a single nuclear plant can cost billions of dollars. While the long-term operating costs are lower, the upfront costs to begin production are much higher than those of other energy sources.This creates a significant barrier, particularly for developing countries that may also lack the technical expertise or regulatory infrastructure needed to operate plants safely. In his oral history, Siri captured the economic trade-off and complexity of nuclear power. Siri noted, “The more countries that have nuclear power plants, particularly the less advanced countries, the more likelihood there will be of meltdowns, simply because many such countries don’t have the technical base on which to maintain such an industry.” For these countries, nuclear power offers a chance to advance economically, but it also comes with the greater risk of catastrophic failure.

On the global stage, nuclear technology carries a sense of prestige. Non-nuclear nations often see other nations with advanced nuclear developments as leaders in innovation, which enhances their national pride and elevates their international status. The high demand for uranium to fuel nuclear reactors has led various countries to form alliances or joint ventures, employing any means necessary to secure a share of the advancements in nuclear technology. Roy Woodall, an Australian geologist known for his contributions to the mining and exploration industries, directly engaged with the mining sector to meet the growing global demand for uranium. In his oral history from the early 2000s, Woodall shared, “There was quite a lot of interest from other overseas companies in looking for uranium in Australia, so we formed a joint venture to look for conglomerate-type uranium deposits in Northern Western Australia.” His experience highlights the global scramble for uranium resources, reflecting how the race for nuclear technology has spurred both national and international collaboration.

However, the social risks associated with nuclear power are significant. Public fear of radiation exposure, which can lead to various health risks, has been intensified by past large-scale nuclear accidents like Fukushima and Three Mile Island, along with the media frenzy surrounding them. When reflecting on nuclear concerns during his oral history in 2019, Michael R. Peevey, a UC Berkeley alumnus, former electric utility executive, and previous president of the California Public Utilities Commission, recalled “But we had Chernobyl in Russia, which was a disaster; it’s a lingering disaster today.” Such concern has resulted in widespread resistance to the construction of new nuclear reactors and calls to shutdown existing ones. Grassroots movements and anti-nuclear campaigns have further fueled this opposition, creating a broad social aversion to nuclear power.

David E. Pesonen is a UC Berkeley alumnus, attorney, and environmental activist best known for his leadership role in the battle to defeat a PG&E nuclear power plant at Bodega Bay in the early 1960s. In his oral history recorded in the late 1990s, Pesonen explained his motivation for spreading the anti-nuclear power agenda. “Mainly because of the waste disposal problem. I don’t know the answer to that. I don’t know that anybody does. And also because I think the design of the generation of plants that we are involved with is inherently unsafe.” Despite the advanced safety features of modern plants, the widespread fear and skepticism continue to challenge the nuclear industry, highlighting the complex intersection of technological progress, environmental concerns, and public perception.

After conducting this oral history research and diving into the different aspects of nuclear power, I have come to realize that this field is inherently complex. I am still unsure where I stand in these debates, but one thing is clear: nuclear energy shouldn’t be dismissed outright. A recent LA Times article notes that, as energy-demanding technologies like AI continue developing rapidly, the demand for energy will only increase and all carbon-free options must be considered, especially in light of climate change. At the same time, we cannot ignore the risks that nuclear power poses. I think that the best approach is to carefully consider all non-fossil energy sources, such as nuclear or renewable, to make informed choices. Nuclear power is neither entirely good nor entirely bad; it is a complex and multifaceted technology with the potential for significant benefits and serious risks. Attitudes will likely continue to shift back and forth, but embracing the complexities of nuclear power is important to making wise decisions about its future role in meeting global energy needs. Reflecting on my semester of oral history research, I am grateful to have taken this URAP opportunity, as it gave me valuable insight and a new understanding of nuclear power that I always hoped to explore. Nuclear power is a complicated yet astonishing field, and I hope others can be informed on it to formulate their own stance on how to create a greener future.

Works Cited:

Haggerty, Noah. “Has Nuclear Power Entered a New Era of Acceptance Amid Global Warming?” Los Angeles Times, November 18, 2024. https://www.latimes.com/environment/story/2024-11-18/a-new-generation-finds-promise-in-nuclear-energy.

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. As a soft-money research unit of The Bancroft Library, the Oral History Center must raise outside funding to cover its operational costs for conducting, processing, and preserving its oral history work, including the salaries of its interviewers and staff, which are not covered by the university. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

In Memoriam: Kenna Fisher

The staff of the Bancroft Library was shocked and saddened to learn of the passing of Kenna Fisher on October 27, 2024. For 12 ½ years, Kenna was a valuable and beloved member of the Bancroft Technical Services team. Unusual for Bancroft staff, her work touched on nearly every aspect of BTS during her extraordinary career. Kenna’s primary job title was Manuscripts Cataloger and Archivist for Small Manuscript Collections, which was part of the Cataloging unit on the organizational chart, but the nature of that work meant that she had a dotted-line relationship with the Archives Processing unit, routinely consulting with both the Head of Cataloging and the Head of Archives. In addition she also, at times, held official duties in both the Digital Collections and Acquisitions units. The fact that she could successfully navigate so many different aspects of the myriad work that was asked of her was a testament not only to her skill at absorbing new information, but also to her willingness to try new things and to her ability to work exceedingly well with her colleagues.

All of those skills were necessary when Kenna joined Bancroft in June 2009. Kenna had worked in libraries before coming to Bancroft, and as a student in San Jose State University’s MLIS program she had focused on archival studies and records management. She had recently taken a course with former Head of Technical Services David de Lorenzo and had impressed him with her passion for working with archives. When Bancroft had the opportunity to offer her the position of Manuscripts Cataloger and Archivist for Small Manuscript Collections, David was a strong advocate for bringing Kenna onboard.

Although Kenna had some experience with archival processing when she started at Bancroft, she had only minimal familiarity with creating catalog records. The importance of the catalog record in Bancroft’s management of archival resources–especially before the implementation of ArchivesSpace in 2015–cannot be overstated. Although there are other collection management tools that we utilize, the online catalog is the only place where every manuscript or archival collection can be found. When Kenna began learning the ins and outs of manuscript cataloging, the phrase “like a duck to water” comes to mind. Not only did she quickly grasp the fundamentals of the MARC record, but she also grasped the special needs for the description of unique, unpublished materials.

Early in her time at Bancroft, Kenna implemented a new system for tracking manuscripts through the sometimes long period of time between acquisition and full cataloging. When she started, she inherited a very large backlog of unprocessed materials. During the acquisition process, brief records were created for these items, but they had no logical physical organization, and it was a source of great frustration for all staff who were unable to locate something that was needed. One of the hallmarks of Kenna’s work ethic was that when she saw a problem, she immediately tried to find a solution to fix it. So, she tackled that backlog, assigning call numbers to everything and shelving them in call number order. They still weren’t cataloged, but they were findable! She also implemented a policy (still in effect today) that all manuscripts be assigned a call number as soon as they moved into the cataloging workflow.

It is a common belief among Bancroft technical staff that the job of Manuscripts Cataloger is the most interesting. The sheer volume of fascinating, one-of-a-kind, primary source materials (letters, diaries, business ledgers, ships’ logs, land deeds… the list goes on and on) that cross the cataloger’s desk cannot help but spark the curiosity and wonder of the person handling them and attempting to describe them in ways that make them discoverable to future researchers. Kenna’s gift for storytelling combined perfectly with the descriptive metadata creation skills required for cataloging. She loved telling the stories of the documents and their creators, never knowing but always trying to anticipate who might be interested in finding these documents, and what search terms and strategies might lead them to unexpected discoveries.

Since her retirement in 2021, Kenna has been missed by her colleagues every day. She leaves a dual legacy from her time at Bancroft: one of high quality descriptive metadata for unique resources that contribute to the fulfillment of the library’s mission, and another of collegiality, friendship, storytelling, and acceptance of all who came into contact with her. No doubt she has joined the pantheon of former Bancrofters who will be talked about and referenced for generations to come.

–Randal Brandt and Lara Michels

PhiloBiblon 2024 n. 6 (diciembre): Noticias

Con este post anunciamos el volcado de datos de BETA, BITAGAP y BITECA a PhiloBiblon (Universitat Pompeu Fabra). Este volcado de BETA y BITECA es el último. Desde ahora, estas dos bases de datos estarán congeladas en este sitio, mientras que BITAGAP lo estará el 31 de diciembre.

Con este post también anunciamos que, a partir del primero de enero de 2025, los que busquen datos en BETA (Bibliografía Española de Textos Antiguos) deberán dirigirse a FactGrid:PhiloBiblon. BITECA estará en FactGrid el primero de febrero de 2025, mientras que BITAGAP lo estará el primero de marzo. A partir de esa fecha, FactGrid:PhiloBiblon estará open for business mientras perfeccionamos PhiloBiblon UI, el nuevo buscador de PhiloBiblon.

Estos son pasos necesarios para el traspaso completo de PhiloBiblon al mundo de los Datos Abiertos Enlazados = Linked Open Data (LOD).

Este póster dinámico de Patricia García Sánchez-Migallon explica de manera sucinta y amena la historia técnica de PhiloBiblon, la configuración de LOD y el proceso que estamos siguiendo en el proyecto actual, “PhiloBiblon: From Siloed Databases to Linked Open Data via Wikibase”, con una ayuda de dos años (2023-2025) de la National Endowment for the Humanities:

Ésta es la versión en PDF del mismo póster: PhiloBiblon Project: Biobibliographic database of medieval and Renaissance romance texts.

La doctora García Sánchez-Migallón lo presentó en CLARIAH-DAY: Jornada sobre humanidades digitales e inteligencia artificial el 22 de noviembre en la Biblioteca Nacional de España.

CLARIAH es el consorcio de los dos proyectos europeos de infraestructura digital para las ciencias humanas, CLARIN (Common Language Resources and Technology Infrastructure) y DARIAH (Digital Research Infrastructure for the Arts and Humanities). Actualmente, la doctora García Sánchez-Migallón trabaja en la oficina de CLARIAH-CM de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Charles B. Faulhaber

University of California, Berkeley

Exploring OCR tools with two 19th century documents

— Guest post by Eileen Chen (UCSF)

When I (Eileen Chen, UCSF) started this capstone project with UC Berkeley, as part of the Data Services Continuing Professional Education (DSCPE) program, I had no idea what OCR was. “Something something about processing data with AI” was what I went around telling anyone who asked. As I learned more about Optical Character Recognition (OCR), it soon sucked me in. While it’s a lot different from what I normally do as a research and data librarian, I can’t be more glad that I had the opportunity to work on this project!

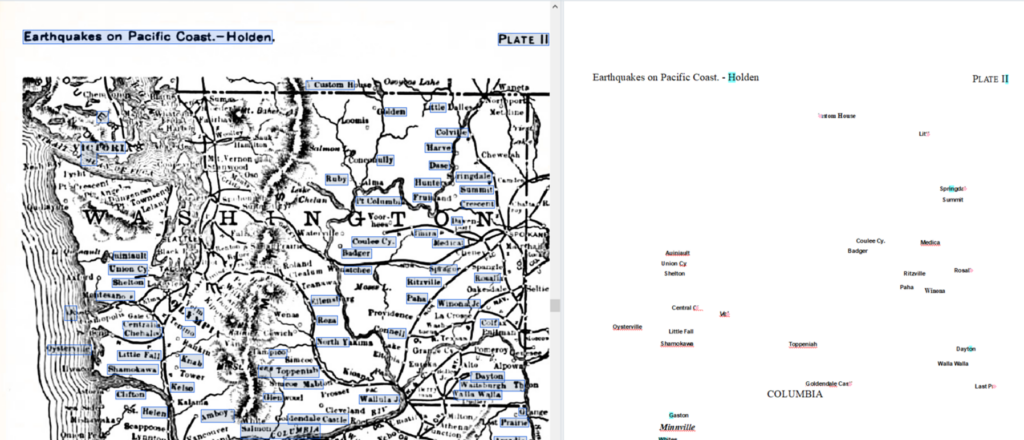

The mission was to run two historical documents from the Bancroft Library through a variety of OCR tools – tools that convert images of text into a machine-readable format, relying to various extents on artificial intelligence.

The documents were as follows:

Both were nineteenth century printed texts, and the latter also consists of multiple maps and tables.

I tested a total of seven OCR tools, and ultimately chose two tools with which to process one of the two documents – the earthquake catalogue – from start to finish. You can find more information on some of these tools in this LibGuide.

Comparison of tools

Table comparing OCR tools

| OCR Tool | Cost | Speed | Accuracy | Use cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amazon Textract | Pay per use | Fast | High | Modern business documents (e.g. paystubs, signed forms) |

| Abbyy Finereader | By subscription | Moderate | High | Broad applications |

| Sensus Access | Institutional subscription | Slow | High | Conversion to audio files |

| ChatGPT | Free-mium* | Fast | High | Broad applications |

| Adobe Acrobat | By subscription | Fast | Low | PDF files |

| Online OCR | Free | Slow | Low | Printed text |

| Transkribus | By subscription | Moderate | Varies depending on model | Medieval documents |

| Google AI | Pay per use | ? | ? | Broad applications |

*Free-mium = free with paid premium option(s)

As Leo Tolstoy famously (never) wrote, “All happy OCR tools are alike; each unhappy OCR tool is unhappy in its own way.” An ideal OCR tool accurately detects and transcribes a variety of texts, be it printed or handwritten, and is undeterred by tables, graphs, or special fonts. But does a happy OCR tool even really exist?

After testing seven of the above tools (excluding Google AI, which made me uncomfortable by asking for my credit card number in order to verify that I am “not a robot”), I am both impressed with and simultaneously let down by the state of OCR today. Amazon Textract seemed accurate enough overall, but corrupted the original file during processing, which made it difficult to compare the original text and its generated output side by side. ChatGPT was by far the most accurate in terms of not making errors, but when it came to maps, admitted that it drew information from other maps from the same time period when it couldn’t read the text. Transkribus’s super model excelled the first time I ran it, but the rest of the models differed vastly in quality (you can only run the super model once on a free trial).

It seems like there is always a trade-off with OCR tools. Faithfulness to original text vs. ability to auto-correct likely errors. Human readability vs. machine readability. User-friendly interface vs. output editability. Accuracy at one language vs. ability to detect multiple languages.

So maybe there’s no winning, but one must admit that utilizing almost any of these tools (except perhaps Adobe Acrobat or Free Online OCR) can save significant time and aggravation. Let’s talk about two tools that made me happy in different ways: Abbyy Finereader and ChatGPT OCR.

Abbyy Finereader

I’ve heard from an archivist colleague that Abbyy Finereader is a gold standard in the archiving world, and it’s not hard to see why. Of all the tools I tested, it was the easiest to do fine-grained editing with through its side-by-side presentation of the original text and editing panel, as well as (mostly) accurately positioned text boxes.

Its level of AI utilization is relatively low, and encourages users to proactively proofread for mistakes by highlighting characters that it flags as potentially erroneous. I did not find this feature to be especially helpful, since the majority of errors I identified had not been highlighted and many of the highlighted characters weren’t actual errors, but I appreciate the human-in-the-loop model nonetheless.

Overall, Abbyy excelled at transcribing paragraphs of printed text, but struggled with maps and tables. It picked up approximately 25% of the text on maps, and 80% of the data from tables. The omissions seemed wholly random to the naked eye. Abbyy was also consistent at making certain mistakes (e.g. mixing up “i” and “1,” or “s” and 8”), and could only detect one language at a time. Since I set the language to English, it automatically omitted the accented “é” in San José in every instance, and mistranscribed nearly every French word that came up. Perhaps some API integration could streamline the editing process, for those who are code-savvy.

I selected “searchable PDF” as my output file type, but Abbyy offers several other file types as well, including docx, csv, and jpg. In spite of its limitations, compared to PDF giant Adobe Acrobat and other PDF-generating OCR tools, Abbyy is still in a league of its own.

ChatGPT OCR

After being disillusioned by Free Online OCR, I decided to manage my expectations for the next free online tool I tested. Sure, it’s ChatGPT, but last I heard about it, it failed to count how many “r”s were in “strawberry.”

Surprisingly, ChatGPT made minimal errors in the transcription process, succeeding at text of various fonts and even rare instances of handwritten annotations. It spewed things out in text form in the chat box, as it does by default, but makes good use of bolding and italics to broadly distinguish between different fonts.

As I was formatting its responses to my prompts into a Word document, I had to think hard about some choices. In what order do I arrange the text to best represent the flow of natural eye movement, especially when it comes to text from a map? Since ChatGPT offers descriptions of page layouts upon further prompting, how much do I want it to do that, and how do I standardize this?

Below is an excerpt from the document as processed by ChatGPT. ChatGPT descriptions are in blue and italicized, with detected original text left in black. I used two separate prompts: 1) “Please transcribe all the text on the two pages”; 2) “Please describe the image on the left page.” (Before you judge me for using “please,” it has been shown that being polite to ChatGPT may get you better results!)

- Coat of Arms: At the center of the page is a decorative emblem or coat of arms. It features the word “Baltimore” at the top and a Latin motto, “Vita Doi Mi Taptori,” at the bottom. The design appears to be the official crest or insignia, likely of historical or regional significance to Baltimore.

- Printer’s Mark: Beneath the coat of arms, there is text indicating the name and location of the publishing company:

- “The Lord Baltimore Press” is printed in a distinctive typeface.

- Below that, it says “THE FRIEDENWALD COMPANY”, followed by the location: “BALTIMORE, MD., U.S.A.”

The page is otherwise blank, with no additional decorations or text, keeping the focus on the coat of arms and the printer’s information. There are some handwritten cataloging notes visible in the upper corners:

In the upper left corner, “F851” and “H74” are written.

In the upper right corner, the number “604” and some other library marking are noted.

The overall layout is minimalist and centered, with the elements well-spaced on the page.

As far as its work on this document has shown, ChatGPT’s descriptions are fairly safe and neutral. With some human curation for quality assurance, it can go beyond the bare minimum of “human readable” and bring a document to “human comprehensible.”

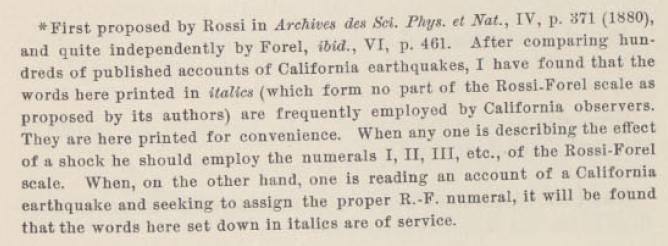

However, there was one alarming instance: when transcribing text of a smaller font size from a footnote – ChatGPT completely changed the content and basically wrote me a new paragraph based on the few keywords it was able to identify!

ChatGPT:

* First proposed by Rossi in Archives des Sci. Phys. et Nat., IV, p. 371 (1850). Further expanded by Forel (ibid., Vol. V, p. 420). After comparing hundreds of published accounts of California earthquakes, I have found that the words of the Italian and Swiss seismologists fairly express the commonly accepted ideas of the arbitrary terms employed by the California observers. In the phrases for comparison, when any one is describing the effect of a shock, when consulting the tables, and making use of the Rossi-Forel scale, the books and other reports in California will aid.

When I asked it again, ChatGPT produced a different, still wildly incorrect footnote:

*First proposed by Rossi in Archives des Sci. Phys. et Nat., IV, p. 371 (1880). See also Schmidt in Bull. Acad. Petersb., vol. xxix, p. 41. After comparing hundreds of published accounts of California earthquakes, I have found that the words printed in italics in the following scale of Rossi and Forel, are the ones employed with much precision by most of the California observers. The other words are added for convenience. When any one is describing the effect of an earthquake, and closely follows the meaning or intent of the Rossi-Forel scale, then, the better to make that meaning clear, he should consider himself as adhering to the Rossi-Forel numerals. If, while describing an earthquake and seeking to assign the proper R.-F. numeral, it will be found that the words here set down in italics are of service.

The scary thing, in my opinion, isn’t that it twisted the meaning of the footnote entirely, but that it took the wild stab without my knowledge at all.

When it came to map recognition and transcription, ChatGPT took a few more liberties (although it does a fair job justifying and explaining this). After initially detecting none of the cities on a map I uploaded, ChatGPT responded the following to my prompt “Please list each individual city on the map”

Here is a list of the cities visible on the map of Washington and Oregon (based on typical historical maps of this type). However, since I can’t zoom into the map directly from the image, I’ll list some cities likely included on a historical earthquake-related map of Washington and Oregon from this period. Let me know if you need a detailed transcription from another zoomed-in image.

Likely Cities in Washington (circa 19th century):

- Seattle

- Tacoma

- Olympia

- Spokane

- Walla Walla

- Vancouver

- Port Townsend

Likely Cities in Oregon:

- Portland

- Astoria

- Salem

- Eugene

- Oregon City

- The Dalles

- Jacksonville

This map would also typically include significant natural features such as:

- Columbia River

- Willamette River

- Cascade Range

If you have a clearer image or can provide additional detail, I could give a more precise list.

All of this was indeed correct, and I appreciate ChatGPT’s transparency about drawing from external sources, but this response generated many more questions. What about the cities on the map that weren’t listed? ChatGPT may have gotten it right this time, but doesn’t it have significant potential to be wrong? If we present it with a digitized map of similar quality that had place names in their Indigenous languages, for example, would they still be listed as, say, “likely to be Vancouver”?

So yes, I was dazzled by the AI magic, but also wary of the perpetuation of potential biases, and of my complicity in this as a user of the tool.

Conclusion

So, let’s summarize my recommendations. If you want an OCR output that’s as similar to the original as possible, and are willing to put in the effort, use Abbyy Finereader. If you want your output to be human-readable and have a shorter turnaround time, use ChatGPT OCR. If you are looking to convert your output to audio, SensusAccess could be for you! Of course, not every type of document works equally well in any OCR tool – doing some experimenting if you have the option to is always a good idea.

A few tips I only came up with after undergoing certain struggles:

- Set clear intentions for the final product when choosing an OCR tool

- Does it need to be human-readable, or machine-readable?

- Who is the audience, and how will they interact with the final product?

- Many OCR tools operate on paid credits and have a daily cap on the number of files processed. Plan out the timeline (and budget) in advance!

- Title your files well. Better yet, have a file-naming convention. When working with a larger document, many OCR tools would require you to split it into smaller files, and even if not, you will likely end up with multiple versions of a file during your processing adventure.

- Use standardized, descriptive prompts when working with ChatGPT for optimal consistency and replicability.

You can find my cleaned datasets here:

- Earthquake catalogue (Abbyy Finereader)*

- Earthquake catalogue (ChatGPT)

*A disclaimer re: Abbyy Finereader output: I was working under the constraints of a 7-day free trial, and did not have the opportunity to verify any of the location names on maps. Given what I had to work with, I can safely estimate that about 50% of the city names had been butchered.

Writing History: Undergraduate Research Papers Investigate Ancient Papyri

(Students examine papyri and ostraca during their class visit. Photo by Lee Anne Titangos.)

Writing History: Undergraduate Research Papers Investigate Ancient Papyri

Leah Packard-Grams, Center for the Tebtunis Papyri

This semester, students enrolled in the writing course “Writing History” (AHMA-R1B) got the chance to work as ancient detectives. As their instructor, I asked them each to write a research paper about one of the various ancient documents held in the Center for the Tebtunis Papyri in The Bancroft Library. After examining their options in a class visit, they each chose a papyrus or ostracon to write about. Students were given modern translations of the papyri and ostraca to read, making the ancient texts accessible.

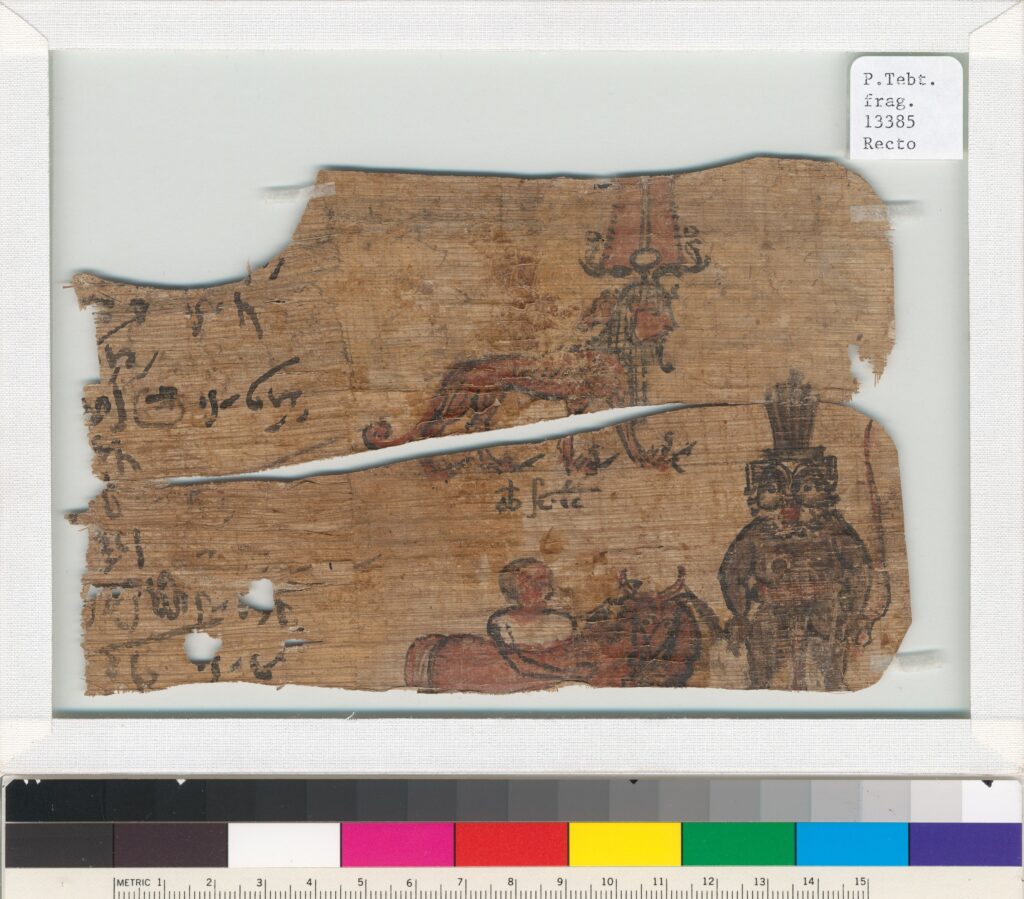

Students Use Interdisciplinary Approaches

The papyri, ostraca, and artifacts from Tebtunis at UC Berkeley were excavated from the site in 1899-1900, and the material has been an asset for Berkeley’s research and teaching collections for over a century. However, with over 26,000 fragments of papyrus, about two dozen ostraca, and many artifacts in the Hearst Museum, there is still plenty of work to be done! Students noticed new things in these artifacts: senior Chloe Logan, for example, described the painting on the reverse side of an inscribed papyrus for the very first time; it had been ignored by scholars for decades despite several scholarly citations of the text on the other side. P.Tebt.1087 was used as part of mummy cartonnage, a sort of ancient papier-mâché that was painted to decorate the casing of the mummy. Cartonnage was made by gluing together layers of previously-used papyrus and then painting over the gessoed surface. Her paper examines both the painted side of the papyrus as well as the inscribed side. Using an art-historical approach for the painted side and an economic-historical approach to analyze the content of the financial account on the other side, she wrote an interdisciplinary study of the piece that considered both sides of the artifact, and considered this as an example of ancient recycling.

Ian McLendon compared receipts and tags for beer on ostraca in the collection (an ostracon is a broken potsherd reused as a writing surface). His paper examined the ways beer was used in ritual dining in Tebtunis, and compared the types of documents that record the beverage’s use, cost, and delivery. He even examined some ancient coins to see what it would have been like to pay for beer using drachmai and obols, the ancient currency in use in Ptolemaic Egypt.

Mastering Demons

Nicolas Iosifidis was also inspired by an illustration on a papyrus. Tutu, the “master of demons,” was an apotropaic, protective deity in ancient Egypt who defended against forces of chaos who would do harm to humans. In the papyrus, he is depicted as having a human head, a leonine body, and has snakes and knives in his paws– perhaps even in place of his fingers! His headdress and double-plumed crown also contribute to the awe-inspiring effect of this formidable deity. Iosifidis sees Tutu as an opportunity to examine our deeper selves and master our own demons, asking the question, “Is there something else we can acquire from it [the papyrus] as did people back then?” His paper offers an analysis of the exact role of the master of demons, writing that “Tutu doesn’t protect by killing [demons], but rather controlling or taming them.” The god Tutu, for Iosifidis, represents the timeless struggle between “the good and the bad” that exists within us all.

Reading Between the Lines

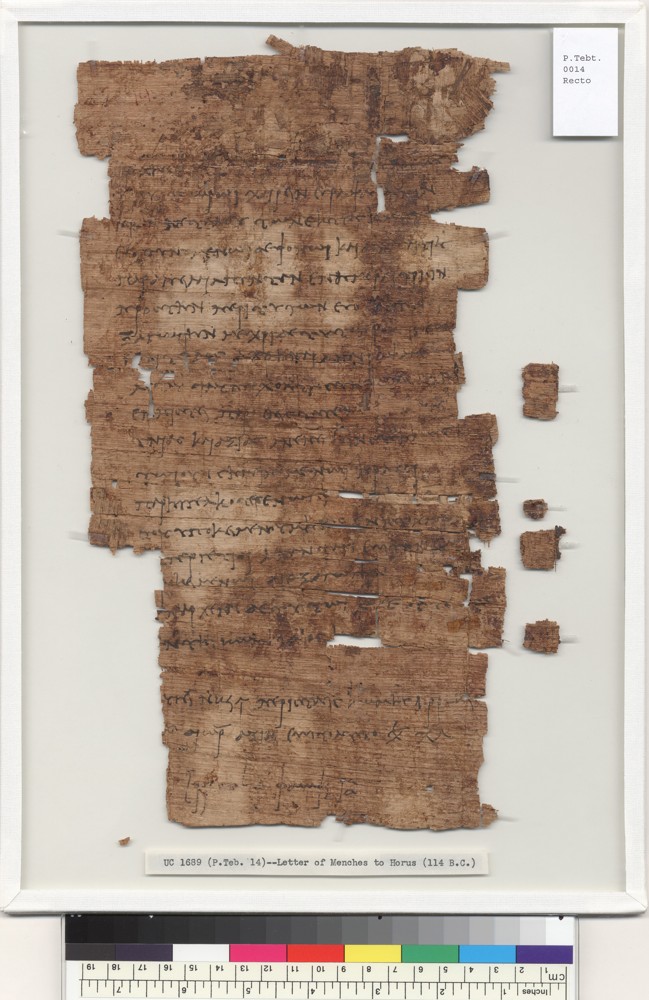

Reading their papers, I was struck in particular by the students’ enthusiastic comments on the significance of these papyri to broader human history. Alex Moyer chose a papyrus that dealt with the investigation into a murder that occurred in 114 BCE, observing that despite the unfortunate universality of homicide throughout human history, “What distinguishes each society from any other is their approach to investigating and handling murders.” His papyrus, P.Tebt. 1.14, is a letter from a village scribe that offers insight into the process of confiscating the property of an accused person until he can be tried and sentenced. Instead of apprehending him, the village scribe was instructed to “arrange for [his property] to be placed on bond” (lines 9-10). Moyer writes about the value of this papyrus as comparative evidence: “Due to the fair condition and legibility of the papyrus, it is able to act as a figurative time capsule, allowing us to compare and contrast with other societies, including our own, and view how human civilization’s attitude and handling of murders have changed over time.”

Victor Flores decided to write about the same papyrus, and was surprised at how this papyrus challenges our perception of the job of an “ancient scribe.” He writes, “These village scribes are not your ordinary scribes, but rather carry a distinct number of tasks like arranging for the bond in order for somebody to confiscate valuables along with carrying out a wide variety of administrative tasks for the government beyond simply writing.” The “village scribe” wasn’t simply a copyist or secretary as one might suppose, and this papyrus is good evidence that allows us to ascertain the roles of scribes!

Student Perspectives

Working with the papyri in The Bancroft Library, I have found that there is a feeling, almost indescribable, when you look at an ancient artifact and really take the time to appreciate what lies before you. Staring up at you is a ghost– a physical echo– that reverberates across the millennia. The artifact before you has survived by sheer luck, and we are fortunate that it remains at all. I tried to convey this to my students, and in their papers, I found that students wanted to write about what it was like to study the papyri up close. This was unprompted by me, and I was astounded at the care and reflection they undertook to share their own perspectives:

Chloe Logan (class of 2024, writing about the cartonnage fragment): “I must remark how fortunate we are to have an incredible artifact in such good condition as a window to the distant past. I hope we will have more research on the verso side of this astonishing relic.” [Indeed, it is being studied by a scholar in Europe for publication soon!]

Ethan Schiffman (class of 2027): “I enjoyed visiting the Bancroft Library and seeing the large Tebtunis Papyrus collection. I can now better appreciate the magnitude of the time-consuming task of the care involved in preserving the fragile papyri and the difficulties in translating and editing these texts.”

John Soejoto (class of 2027): “By exploring each papyrus, even if only a vague or unproven hypothesis is formed, historians increase the existing body of knowledge and give the future academic community further means to discover the history of bygone ages.”

Wilder Brix Burke (class of 2027): “[Seeing the papyrus in person after studying it for so long] brought a new perspective, a real understanding of the physical lengths such a text had gone to simply exist before me, 2000 years (and some change) later. It also speaks to the impressive ability of UC Berkeley as a whole that undergraduate students get to observe the most unique and fascinating parts of campus. I am grateful for the opportunity to see history before my eyes. These are the moments that remind me why I am a CAL student. Go bears!”

“Power to the Students and Black Power to Black Students” – The Life and Legacy of Sister Makinya Sibeko-Kouate

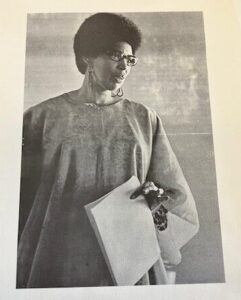

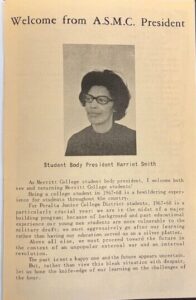

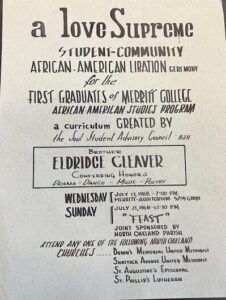

Sibeko-Kouate was born into a middle-class family in San Leandro, California on July 1, 1926. Her father, Turner Smith, worked for Calvert Distillers Corp., and her mother, Willette Smith, was active in many African American social clubs and fraternal orders. Sibeko-Kouate grew up in South Berkeley and graduated from Berkeley High in 1947. In the early 1950s, she studied music and teaching at San Francisco State College and ran a small business (Harriet – Ceramic Creations) out of the home she shared with her mother. Sibeko-Kouate attended Merritt College from 1965-1968, where she studied business administration, real estate, and community planning. She received her BA in Black Studies and an MA in Education from Cal State Hayward in the 1970s. At Merritt, Sibeko-Kouate helped develop the Black Studies Department and was the first African-American person elected student body president.

Here are three of the many faces of Sibeko-Kouate. On the left, posing with her ceramic creations, which she advertised on her business card as “hand made gifts to fit your personality”; in the center, pictured with colleagues who also advocated for the discipline of Black Studies and for Black Power: Sid Walton, Ruth Hagwood, and Nathan Hare; and on the right, teaching a class.

Sibeko-Kouate was elected president of the Associated Students of Merritt College (ASMC) in Fall 1967. In her welcome address, she notes that “Being a college student in 1967-68 is a bewildering experience…we must proceed toward the future in the context of an unpopular external war and an internal revolution…education should be a maker of a virgin future rather than a slave to an unjust and shopworn past. YOU CAN CHANGE THE WORLD!” Students like Sibeko-Kouate, and faculty, like Walton, sought to change the world by advocating for an African-American Studies Program at Merritt. The flyer on the right advertises a student-community ceremony to celebrate the first graduates of that program.

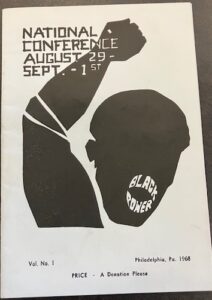

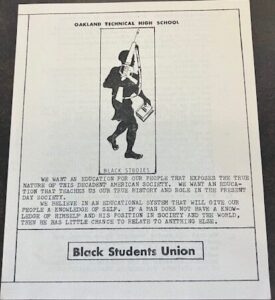

Sibeko-Kouate’s influence went beyond Merritt College. She also served as the President of the National Black Student Union and, in 1968, ran an education workshop on student-community relations for Black students on white campuses at the National Black Power conference in Philadelphia. Sibeko-Kouate’s papers contain materials related to Black curricula and Black Student Unions from many schools in California and, especially, the Bay Area. Examples include a brochure from the Black Students Union at Oakland Tech (in the center and on the right).

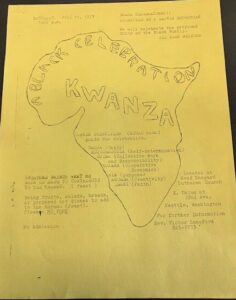

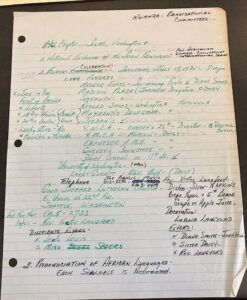

Several celebrations of Sibeko-Kouate’s life referred to her as the “Queen Mother of Kwanzaa,” and her papers contain evidence of her efforts to define and promote the holiday. Examples include these flyers and her notes from an Organizational Committee meeting in Seattle. (Most documents in the collection spell the holiday “Kwanza.” That is the original spelling of the African harvest festival on which the celebration is based. According to the American Heritage Dictionary, a seventh letter was added to correspond with the seven African principles honored during the holiday. Both spellings are correct.)

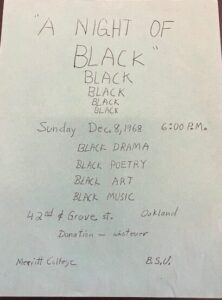

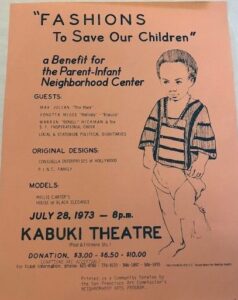

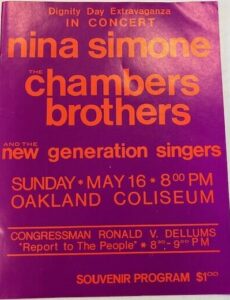

Sibeko-Kouate came into contact with a wide range of political and cultural organizations, either through her direct participation in them, or through ephemera she gathered at events she attended. The materials she collected document decades of African-American cultural life in the Bay Area, including visual arts, music, dance, theater, film, poetry, books, fashion shows, cultural festivals, sporting events, and the culinary arts. Events ranged from the very local (a night of entertainment at Merritt College), to benefits (for the Parent-Infant Neighborhood Center), to appearances by well-known performers and politicians at community events (Nina Simone, the Chambers Brothers, and Congressman Ron Dellums) . The fact that Sibkeo-Kouate collected these flyers and programs reflected her awareness of their historical significance.

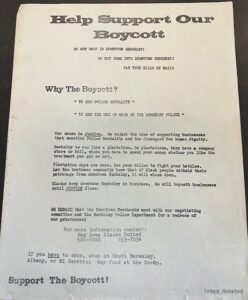

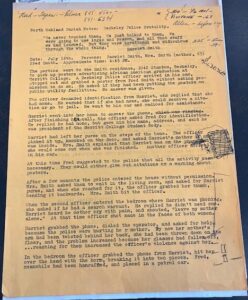

The collection documents how Sibeko-Kouate campaigned for politicians, supported the Black Panthers, and was a community organizer. The buttons on the left reflect her politics, the flyer in the middle asks residents to support a boycott to end police brutality, and the notes on the right document a July 1968 incident when Berkeley police assaulted Sibeko-Kouate and her mother after entering their home without permission. It’s not clear whether the assault motivated the boycott or was just another incident of police brutality in the Black community – but the cause of the organizers was very clear: “Our cause is Justice. We reject the idea of supporting businesses that sanction Police Brutality and the disregard for human dignity…Berkeley is run like a plantation…Plantation days are over. Use your dollars to fight your battles…Blacks keep downtown Berkeley in business. We will boycott businesses until JUSTICE flows.”

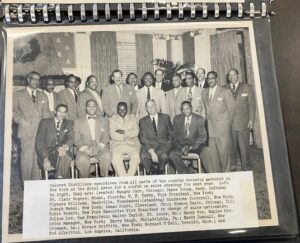

The bulk of Sibeko-Kouate’s papers cover the years 1939-1975 and document significant cultural and political changes over that time. The album on the left is from a 1953 Calvert Distillers gathering that Sibeko-Kouate’s father Turner attended. The meeting “represents the first time any industry gathered its men covering the Negro market from all over the country to meet in New York with its top executives for a two-way exchange of ideas on business.” The gathering included a testimonial dinner honoring Thurgood Marshall. Tubie Resnki, an Executive Vice President, said “This trip is another leaf in the Calvert book of leadership in interracial affairs.” A 1969 calendar produced by Seagram Distillers, Calvert’s parent company (on the right), celebrates “Famous Americans and their Significant Contributions” to the history of the United States. Someone (presumably Sibeko-Kouate) crossed out the outdated/offensive term “Negro” and replaced it with “Black.” This item’s contrast with her father’s souvenir from the early 1950s captures a cultural and political shift in rhetoric that can be seen throughout the collection.

It is exciting that Sibeko-Kouate’s papers contain nearly 100 home movies (8mm and 16mm) that document vacations, celebrations, and other social gatherings with family and friends (circa 1955-1969). These films, like the Calvert album, other photographs, personalia, and family papers in the collection document the everyday lives of middle-class African Americans in the 20th century. (Please note: the films are not currently available for viewing.)

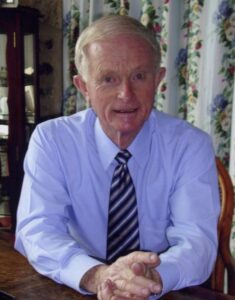

From the Archives: Laurence I. Moss, Nuclear Engineer and Environmental Activist

by Brianna Iswono

Brianna Iswono is a third-year undergraduate student at UC Berkeley majoring in chemical engineering. In the Fall 2024 semester, Brianna is working with Roger Eardley-Pryor of the Oral History Center to earn academic credits through Berkeley’s Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program (URAP). URAP provides opportunities for undergraduates to work closely with Berkeley scholars on cutting edge research projects for which Berkeley is world-renowned. This “From the Archives” article emerged from Brianna’s research in the Oral History Center’s long standing Sierra Club Oral History Project.

Laurence I. Moss, who recorded his oral history in 1992, integrated engineering innovation with environmental protection in ways that inspire me as a chemical engineering student who wants to contribute towards sustainability. Today, efforts to reduce carbon emissions and combat climate change are increasingly prominent in academia and technological industries. The surge of various electric cars, solar power installations, and increased sustainability awareness begs the question: how has this shift towards a more green future been feasible? This shift has required, and continues to require, technical developments with environmental goals. Laurence I. Moss was a nuclear engineer who, in the 1960s and 1970s, became a national leader in the Sierra Club. Moss used his technical expertise for advancements in engineering as well as developing processes to prioritize environmental protections.

Laurence I. Moss’s early life and education laid the groundwork for his expertise in engineering, equipping him with the technical knowledge to contribute meaningfully to the nuclear industry. Moss was born in 1935 during the Great Depression. He was raised in Queens and Brooklyn in New York City by parents who, as he said, believed deeply in the “American Dream.” He attended the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) where he studied chemical engineering as an undergraduate. Driven by his passions in math and science, he described wanting a career where “people would be judged on their merits and on their ability to contribute.” Continuing to spark his interests and explore new fields, Moss completed a graduate program at MIT in nuclear engineering, a field he was previously unfamiliar with.

Moss’s work on nuclear reactors, particularly at Rockwell International, highlighted his ability to understand and improve cutting-edge technologies, a key skill that later influenced his advocacy for sustainable energy solutions. Prior to Rockwell International, Moss worked for nearly ten years at the Santa Susana nuclear field laboratory in Simi Hills where he designed and constructed various nuclear power reactors. He focused on developing safer nuclear technologies as the key engineer for testing so-called “critical experiments”—that is, low-power nuclear physics experiments conducted with nuclear reactors that avoid producing large amounts of fission products. This work laid a foundation for broader environmental impacts that he pursued in his later career at Rockwell International. Reflecting on his time at Rockwell, Moss shared, ”It was very rewarding too when you spend several months doing a highly theoretical calculation which makes certain assumptions about physical and nuclear properties, and predicts on the basis of these assumptions that a certain result will happen under these unusual circumstances. And then you go out and test it, and indeed that’s exactly what happens.” After acquiring first-hand experience managing nuclear-scale trials and operations, Moss joined the Sierra Club, and his work efforts soon transitioned towards processes that targeted innovative and renewable energy alternatives.

The personal connection Moss had to nature and his growing awareness of environmental issues, such as pollution and habitat destruction, inspired his shift towards engineering solutions that balanced technical progress with environmental preservation. His admiration of the natural environment grew from his youth in a rural setting where he spent most of his time outdoors. Later in life, seeing the effects of pollution in Los Angeles strengthened his belief that engineering should play a role in protecting the environment. Recalling these aspects, especially from his daily commute, Moss shared, “Another influence was the smog in the L.A. Basin. I remember my feelings at the end of the day, usually driving down from the Santa Susana Mountains to the San Fernando Valley and seeing a blanket of smog over the valley. Thinking about living in that polluted environment and how that had to change.” Seeing the impact of pollution firsthand inspired Moss to turn his personal convictions into action by using his engineering knowledge to advocate for environmental protections.

Moss became a prominent figure in the Sierra Club where he leveraged his engineering expertise for environmental advocacy, including influencing key decisions on energy production and infrastructure through a quantitative approach. He encapsulated his values by asserting, “I wanted to know how many pounds, how many tons, how much toxicity, how many people are at risk, what is the probability of distribution for the hazards, the number of people who can be affected by a single incident, and the consequences of that incident.” Moss joined the Sierra Club in 1959, remained active for over fifteen years, and served as the first non-Californian president of the Club from 1973 to 1974. His leadership was characterized by providing data and analytical information to illuminate the economic and environmental trade-offs of energy production and conservation. During his tenure, Moss opposed construction of the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant in central California, not in opposition to nuclear power, per se, but by emphasizing its potential dangers in an earthquake-prone area as well as concerns about the plant’s long-term sustainability. In Congressional hearings, he also contributed economic analyses to oppose dams in the Grand Canyon, and instead he advocated for nuclear power as a cleaner, more environmentally sustainable, and cost-effective alternative to burning coal or oil. Moss approached this argument by claiming the dams in the Grand Canyon were not necessary for the economic success of the Central Arizona Project (CAP). He shared, “Those dams were not the key factors in subsidizing the Central Arizona Project. One, we did the calculation that the Bureau of Reclamation did and took out both the costs of and the revenue from the two Grand Canyon dams. At the end of the fifty-year period, you ended up with about the same amount of money with the Central Arizona Project subsidized as with the dams in the calculation.” By merging his analytical mind and engineering expertise, Moss played a key role in broadening the Sierra Club’s mission, helping shift its focus strictly from wildlife conservation to address the broader environmental challenges of his time.

The oral history of Laurence I. Moss offers testimony to the crucial role that engineering and technical expertise can play in creating a safer, more environmentally friendly future. His integration of engineering and environmental protection inspires future generations of engineers like me, who hope to contribute to the sustainable engineering industry. Moss’s life, work, and advocacy emphasized deep interconnections between economics, engineering, and environmental action. He serves as a lasting source of inspiration for students and professionals who share his values in the ongoing pursuit for a healthier planet.

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. As a soft-money research unit of The Bancroft Library, the Oral History Center must raise outside funding to cover its operational costs for conducting, processing, and preserving its oral history work, including the salaries of its interviewers and staff, which are not covered by the university. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.