Tag: oral history center

Celebrating the Work of Freedom to Marry, Through Oral History

By Katie Gonzales

The Oral History Center’s Freedom to Marry collection features interviews from key members of the Freedom to Marry organization. Officially launched in 2003 by Evan Wolfson, the campaign worked to legalize same-sex marriage across the United States. The campaign originally worked on helping same-sex couples get married on a smaller case-by-case scale, as at the time, no state in the country had legislation protecting same-sex marriage. The first state to even do so was Massachusetts in 2004. Throughout the organization’s lifespan, same-sex marriage went from being legally unprotected on a state level to federally protected as an unequivocal right across the United States.

However, in June 2024, the Supreme Court countered this ruling in Department of State v. Muñoz, in which it declared that the right to bring a noncitizen spouse to the United States is not constitutionally protected. This ruling could be detrimental towards married same-sex citizens and noncitizens who would have to leave the United States, a country where their marriage is legal, back to a home country where it isn’t.

Given the June 2024 Supreme Court ruling, as well as this being Pride month, it’s a great time to look back on the work that Freedom to Marry did to legalize same-sex marriage. The lessons from the organization remain as important today as they were twenty years ago. When initially proposing the Freedom to Marry campaign to potential investors, Wolfson remembers:

I would be saying things to them like, look, if you just want to sprinkle some money around and do some ordinary building programs and helping people, I’m not the right person for you. And if you want to stay in your work up till now, which has been primarily in the Bay Area, and certainly only in California, not nationally, I’m definitely not the right guy for you. But if you really want to make a difference, what you really ought to do is support a campaign to win the freedom to marry. They went, “Marry?” “Yes, marriage. Marriage is the engine of change, marriage is what we’re going to have to be fighting for. You can do good work this way, but if you want to be transformational, you need to do this.”

One major battle that Freedom to Marry faced was when Proposition 8 passed in California. This ballot proposition intended to ban same-sex marriage measure passed in 2008. At the time, this was a massive blow to Freedom to Marry’s campaign, especially due to California’s reputation as a more progressive state. Tim Sweeney, a member of Freedom to Marry’s board of directors, recalls:

We were just devastated. It was devastating. Right? In California, the progressive beacon of the west, right? And we lost handily. It wasn’t close, which would have just taken a bit of the sting out of it. But what was interesting is the number of non-LGBT people who were outraged that their friends and family that they loved and cared about were basically being told you’re second-class citizens and your love is not legitimate. It created such a wave of we’re going to commit ourselves to fix this. And we have to be willing to be with them in their anger, invite them in in a new way, let them lead with us. All of that is hard to do, I think, in a social movement because you get worried they don’t really get it, their message is not your message, are they going to do some half measure, are they going to compromise, what do they know? But you got to kind of trust that they’re with you and you got to really in some cases step aside and realize, for instance, the message you may say to yourself or within the community is different than the one the non-LGBT community needs to hear. And maybe they need to have different messengers that just talk about the journey in a way that maybe an LGBT person wouldn’t sound authentic or real on. So that was just such an interesting moment. It’s almost like after Prop 8 we needed to step back a bit and let the world realize, “Wait a minute, what happened here? This is not okay.”

After the loss in California, support for LGBT rights increased due to the sheer amount of media coverage of the loss nationally. A Pew poll from 2010 cited that over 60% of Americans supported same-sex marriage, a drastic difference from polls in the 1990s that cited 60% of Americans against same-sex marriage. But by 2012, President Barack Obama made his support for same-sex marriage clear, stating that his views had “evolved” since his first presidential term. Thalia Zepatos, the Director of of Research and Messaging for Freedom to Marry recalls in her 2016 interview the impact of Obama’s statement:

I think really two things happened. One was that Governor [Martin] O’Malley really got involved in the campaign, but the big one was that our long-term effort to really engage the White House and President Obama came to fruition, you know not long before the election and President Obama made his statement in support of same-sex marriage, and within twenty-four hours, polling support for marriage among black voters in Maryland went up by twenty points. I mean, it was the biggest single day increase I’ve ever seen anywhere and I think it contributed just in a very great way.

By 2015, 37 states had legalized same-sex marriage, but it would not be a federal right until the Supreme Court case of Obergefell v. Hodges, which argued that same-sex marriage was a right under the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause and Equal Protection Clause. On June 26, 2015, the Supreme Court announced its ruling: same-sex marriage was guaranteed as a fundamental right. The same night, the White House was bathed in rainbow lights, an unmistakable show of support for the ruling. Jo Deutsch, Freedom to Marry’s federal director from 2011-2015, recounted this event:

It was a truth that, from every level, we had won. It was an acknowledgement from the President of the United States that our lives and our marriages mattered, in a just obvious way…This is the symbol of America and the symbol of the President of the United States, all in rainbow color. It was just breathtaking and so beautiful…We had come so far through our lives from asking can we walk down the street holding hands, or can we actually, in an introduction, say this is my wife? And now to this moment, there we were in front of the White House, in all of its colorful glory, with all of these people holding hands. I can’t tell you how many proposals we saw, with people just dropping to their knees right and left. It was like, another one dropping to their knees, and everybody started to clap. It was just phenomenal.

As the end of Pride month nears, it is important to remember that it hasn’t even been 10 years since the legalization of same-sex marriage in the United States. In many other countries around the world it is still taboo or even illegal. When we celebrate Pride month, it’s important to remember the work that many people and organizations did to ensure LBGTQIA rights, especially as they continue to face challenges. Celebrations can only happen as a result of triumph over tribulations, and should be remembered together.

Katie Gonzales is currently a third-year student at UC Berkeley studying English and Anthropology. She works as a student editor for the Oral History Center.

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

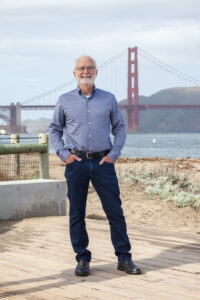

New Oral History from the OHC – Greg Moore: Executive Director of the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy

The San Francisco Bay Area is known for the kind of environmental advocacy that has become a model for regions around the country. There’s a long legacy, spanning decades, of people behind this work. Greg Moore is one of these people. Greg has dedicated his career to conserving public lands and making parks accessible for all. He, too, has become a model, someone to whom people throughout the country – and world – look for guidance.

Greg served as the executive director of the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy from 1986 until his retirement in 2019. The GGNPC was founded in 1981 and its mission is to preserve the Golden Gate national parks, enhance the park visitor experience, and build a community dedicated to conserving the parks for the future. But his work in the environmental sector began long before 1986, dating back to his time as a student at UC Berkeley in the newly-formed Conservation of Natural Resources School and College of Environmental Design, during the environmental decade of the 1970s when the Environmental Protection Agency was formed and regulatory laws, like the Clean Water Act, were passed. And even before that, when he was a ranger with the National Park Service.

I had the privilege of sitting down with Greg in 2022 to interview him about his life and work. In preparation for the sixteen hours I would end up spending with him, I spoke with a number of people who know him in different capacities – former fellow National Park Service rangers; as well as Conservancy board members, employees, and donors. One thing was clear: Greg is universally respected for his work and his collegiality. I kept hearing about how, as both a colleague and manager, he listened to people and carefully considered their perspectives. About how, as the executive director of the Conservancy, he wrote heartfelt letters to board members each year, letters that they all not only save, but cherish. About how he would write and perform in an annual musical parodying popular songs for year-end parties.

But what struck me the most was how present Greg was during each phase of our interview sessions. Whether we were discussing how he developed a love for music as a child; his studies at Cal and then later at the University of Washington; meeting his wife, Nancy, and raising their son; or his love for parks; the development of his career; managing a large staff and multi-million dollar fundraising campaigns; and working to make parks accessible for all, Greg took every question I asked seriously, responding sincerely and weaving in humor throughout.

Greg is perhaps best known for his work with the Conservancy. He played a role in the creation of the organization, which he discussed in more detail in his oral history, before becoming the executive director. There are an incredible array of projects on which he worked during his tenure with the Conservancy, like various habitat restorations, converting the Presidio from an Army base to a park, transiting Fort Baker from a military base into a national park, promoting citizen science through the Golden Gate Raptor Observatory, transforming Crissy Field into one of San Francisco’s crown jewels and creating the beloved Crissy Field Visitor Center, developing community partnerships and youth programs, and shepherding the Tunnel Tops project into existence. The list goes on.

The underlying theme of each of these projects was the drive to make parks accessible for everyone. “Parks for All” is the beating heart of the Conservancy’s mission. Here’s what Greg said about the origin of the mission:

“The ‘Parks For All’ came when the Conservancy was trying to think through how to simply and straightforwardly describe our mission. The Conservancy had a mission statement, but like many it was probably twenty-five to thirty words long, and I began thinking about how to put that in simple words that were very direct and, in some way, have the power-of-three impact. That’s when I began thinking, Well, of course, we’re about ‘parks.’ These are the physical places that we need to transform and enhance. Then we’re about ‘for all’ because these places are owned by every person in the United States as national parks, and then our final responsibility is ‘forever’ – to pass them from one generation to the next. It not only summarized our mission but almost described a theory of change that first you have the places and to make them for all youth to improve and enhance them. You have an opportunity to engage people in their enjoyment, in their stewardship, in their contributions for all, and then finally all the restoration work that cares for these places that you’ve enhanced and taken care of.”

Greg wanted to make sure people were aware that the parks existed, they felt comfortable there, and that they were relevant to the visitor’s life experience. He did this by bringing communities into planning conversations, implementing a bus route that would drive people from their neighborhoods to the parks and then back again, partnering with public libraries, and creating a multitude of programs – for kids, related to art, and citizen science for civilian park goers. Greg’s commitment to the Conservancy’s simple mission is what made the organization so successful and such an integral part of life in the Bay Area. And Greg’s interest in working with communities and listening to people – his colleagues, board members, donors, and park users alike – is what has made him such a towering figure in the Bay Area’s environmental movement.

It is with great excitement that we announce Greg Moore’s oral history is now publicly available.

Out of the Archives: Patrick Hayashi: From Mail Carrier to Associate President to Artist

by Zachary Matsumoto

“My mom told me that an old deaf man, Mr. Wakasa, was walking his adopted stray dog around the perimeter of the camp,” recalled Patrick Hayashi. “His dog caught in the barbed wire fence and Mr. Wakasa went to save him and release him. The sentry ordered him to back away from the fence, but because he was deaf, he couldn’t do it, and so the sentry shot and killed him.”

This is the story of James Wakasa’s murder, which Patrick Hayashi’s mother told him when he was growing up. Wakasa was one of over 100,000 Japanese Americans incarcerated by the US government during World War II. In the incarceration camp of Topaz in the desert of central Utah, an armed US soldier shot and killed Wakasa. His death sparked outrage among Topaz’s incarcerees. Although individuals in the Japanese American community contest some of the details of Wakasa’s death, it remains a key, painful moment in the incarceration experience that Japanese Americans have passed down to their children.

The story of Wakasa’s death certainly remained an important memory for Hayashi, a Sansei—or third generation Japanese American—who was born in Topaz while his parents were unjustly imprisoned there. Hayashi discussed his life and career with the Oral History Center at UC Berkeley. His interview was conducted as part of the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project, which explores trauma and healing across generations for Japanese Americans whose families were incarcerated during World War II.

As a young boy, after their release from the prison camp, Hayashi grew up with his parents in Hayward, California. His mother maintained ties to the Japanese American community, largely through church. However, when he was still young, Hayashi’s mother passed away of heart failure. This deeply saddened Hayashi’s father, who now carried the responsibility of raising a family as a single parent. Additionally, according to Hayashi, his father must have felt the guilt and shame from his incarceration experience in World War II. Nonetheless, Hayashi’s father exhibited resistance. He was a “no-no,” meaning he said “no” to two questions in an infamous loyalty questionnaire the US government forced upon the imprisoned Japanese Americans during WWII. The questions asked if one would be willing to serve in the US Army, and if one would swear loyalty to America and rescind loyalty to Japan. This sparked outrage among the Japanese American community, who were asked to serve a country that imprisoned them, and rescind a fealty to Japan that they didn’t have. Hayashi’s father’s “no, no” response was, as Hayashi believed, a “principled stand” against these unreasonable questions.

But his father never mentioned this resistance until Hayashi was an adult. Like many post war Japanese American families, Hayashi’s family did not often discuss their incarceration experiences.

Similar to his father, Hayashi also recalled feeling shame and guilt around incarceration and the war. In high school, he felt particularly ashamed of his identity when his class discussed WWII and the atomic bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki. At that time, Hayashi later recollected, “I was preferring not to be Japanese.” He also experienced a disconnect with the Japanese American community, largely due to his mother’s passing.Nevertheless, Hayashi shared many fond memories of his childhood, from reading Sherlock Holmes and science fiction books as an elementary schooler to becoming a star tennis athlete in high school.

If Hayashi felt shame due to his family incarceration, he channeled it into his work, starting in the 1960s. When reading his oral history, I noticed a theme of activism exhibited across his career in a near continuous fight for justice. After dropping out of college and working as a mail carrier, he found his calling in literature and became a UC Berkeley professor in the newfound Asian American Studies Department—one of the first such departments ever created. These developments for Hayashi came at the time of 1960s social movements in America. In one such movement, student protests in California universities led to the creation of an Ethnic Studies program at UC Berkeley.

Hayashi later became involved as a UC administrator, first working for Cal as the head of Student Conduct. After an investigation revealed that UC admissions were discriminating against Asian American applicants in the 1980s, Hayashi was appointed Associate Vice Chancellor of Admissions and Enrollment. In this position, and later as Associate President in the University of California, Hayashi worked on policy development and acted as an advocate for student applicants. He played a key role in fighting unfair admissions policies, such as the National Merit Scholarship Program (for discriminating against marginalized groups) and the Scholastic Aptitude Test or SAT (for not only explicitly favoring privileged students, but for also being, as Hayashi noted, a “bad test”).

One example of his advocacy came through at a meeting he attended soon after becoming Associate Vice Chancellor. In this meeting, Harold Doc Howe, Lyndon B. Johnson’s former Secretary of Education, communicated views with which Hayashi disagreed. Despite feeling nervous, Hayashi publicly challenged Howe in front of his colleagues. “My hands are actually trembling visibly in front of me and I said, ‘Howe begins with the assumption that a person’s writing ability reflects that person’s thinking ability. I don’t begin with that assumption. Instead I turn it into a question, and the question is to what extent does a person’s writing ability reflect that person’s ability to think?’ I said, ‘When you pose it as a question, the answer becomes obvious, it depends. If a person is new to the country or if the person is poor and has attended poor schools where the quality of education is low, then it’s incorrect and unfair to think that a person’s writing ability reflects that person’s thinking ability. Because oftentimes people just haven’t had the opportunity and the assistance to develop writing ability.’”

This, to me, demonstrates Hayashi’s sense of right and wrong – a fight against prejudiced assumptions in the admissions process.

Over time, too, Hayashi started to come to terms with the incarceration experience that his family hardly discussed and loomed over him like a cloud. One key moment for him occurred during his work as a UC professor. After reading James Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son, in which Baldwin discusses his experiences with racism and understanding the good his overbearing father did, Hayashi felt a better understanding both of his own father and his emotions. According to Hayashi, “[Baldwin] helped me understand my rage. And how if you’ve been suppressed constantly by racism, that goes somewhere and then it explodes. That was my pattern, and then it made me realize that it must have been my father’s experience as well. He was a proud man, he was smart, but it was clear, the injustice was clear to him and so it must have gone somewhere.”

To me, Hayashi’s understanding of Baldwin speaks to the emotional scars of incarceration that burdened many Japanese Americans. After experiencing racist injustice during World War II, anger would seem like a reasonable response. Perhaps the silence of many Japanese Americans after the war was the product of the internal, bubbling anger that people of color have felt throughout American history.

As Hayashi continued to come to terms with his family’s incarceration experience, James Wakasa’s story reemerged as an important moment. In the late 1980s, Hayashi visited an art exhibition from the incarceration camps, filling him with emotion. He recalled, “I choked up more and more and then the fourth painting I saw was Chiura Obata’s sumi-E sketch of James Wakasa falling over after he was shot, and I started to sob. It was terribly embarrassing, but everyone around me was mainly Nisei, they were crying too. That’s when I started revisiting the camps in a systematic way.”

Hayashi held true to his word. Later in life, he became more and more involved in the memorialization of Topaz, the camp of his family’s imprisonment. After retirement from Cal, Hayashi played a role in the creation and work of the Topaz Museum, located near the site of the former incarceration camp. He taught workshops at the museum for teachers in Utah, served as the keynote speaker at a 2016 Day of Remembrance event, and interviewed the Topaz class of ‘45—high schoolers who graduated in 1945 as Topaz incarcerees. Hayashi also took up painting as a major passion and a creative expression of his identity.

Hayashi’s life story is a reminder that one does not need to be defined by internalized pain of the past, but can instead come to terms with that pain and tell its story. The interviews and life stories told throughout the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project illuminate themes of memory, belonging, and healing. Hayashi’s life fully demonstrates each of these themes and serves as an inspiration for Japanese Americans pained by the past but who also want to make a difference.

To this day, he remains active in preserving the memory of incarceration. In 2016, Nancy Ukai, an activist who fought the auctioning of incarceration art, approached Hayashi with a request to create a painting for a Day of the Dead altar at a Japanese American cemetery. The request? To paint James Wakasa’s soul. His story, a source of intergenerational pain and important in Hayashi’s own life, now lay in the hands of Hayashi: a man who healed.

Patrick Hayashi’s oral history transcript is available on the OHC’s website.

Zachary Matsumoto is a sophomore at UC Berkeley currently studying History and participating as an Oral History Center URAP apprentice. He was drawn to the Oral History Center after attending a Bancroft Roundtable presentation about the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project. American history is a current academic interest of his, including the histories of communities relating to his background as a Chinese and Japanese American. In his free time, Zachary likes to go for runs, watch sports, and play taiko.

OHC Staff Reflects on 2023

The Oral History Center has been as busy as ever this year, publishing hundreds of hours’ worth of interviews online. On top of making this wide range of voices available to the public, my colleagues have also used these collections of The Bancroft Library to interpret, frame and share new stories about our past. In November, the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives project was launched, featuring interviews with the descendants of the incarceration camps during World War II. Not only are the transcripts online, but there is also a podcast and a deeply moving work of graphic illustrations that draw meaning from the interviews. In October, Todd Holmes and Roger Eardley-Pryor designed, wrote, and launched a new museum exhibit, Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism at the Bancroft Library Gallery, which runs through November 2024. There is an accompanying digital exhibit, which will feature podcasts, mini-documentaries, and a curriculum guide for students and teachers that will live on long after the gallery exhibit closes.

Center staff showed great leadership in the field of oral history. There is always lots to say about our oral history education programs, but what was new this year was OHC participation in a pilot historical methods course for undergraduate majors of UC Berkeley’s history program. Oral historian Shanna Farrell took a seat this year on the council of the Oral History Association, and Amanda Tewes and Roger Eardley-Pryor also led panels and gave papers at the OHA annual meeting. Todd Holmes, together with our Advanced Institute alum Emi Kuboyama, won the Autry Prize from the Western History Association for their documentary on the redress of the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.

Communications and editorial lead Jill Schlessinger created, oversaw, and updated our editorial process. On the back end of our production, David Dunham led the team that transferred and preserved almost two thousand hours of audio-video that was trapped on defunct recording formats. Of course, we couldn’t have done this work without the help we get from student employees in production, preservation, and communications. Finally, following a competitive national search, I would like to celebrate the arrival of the new historian of science, technology, and medicine, Liz Semler.

I want to thank every member of the OHC staff for a great year! From all of us, we wish you all a peaceful and magical holiday and a wonderful 2024!

–OHC Director Paul Burnett

OHC Staff Reflections

I am grateful to have celebrated my 21st year with the Oral History Center. It is a privilege to support the efforts of our interviewers in producing the array of oral histories produced this year. I relish the opportunity to work with student workers, undergraduate research apprenticeship program [URAP] participants, and librarian interns. Students are integral to our production and preservation processes, ensuring that our transcripts, audio, and video are accessible and preserved. They also bring new perspectives and insights into our oral histories. It’s a cliche to say win-win, but our student workers and interns consistently share how participating with the OHC enriches their academic, intellectual, professional, and human interests. We could not do a fraction of the work we do without them. Special thanks this year to the following students and interns that contributed in countless ways to the OHC: Max Afifi; Sadie Baldwin; Peter Beshay; Hue Bui; Mina Choi; Georgia Cutter; Jason de Haaff; Nikki Do; Ava Escobedo; Leah Freeman; Samantha Goodson; Meiya Gujjalu; Anthony Lin; Lina Matine; Solomon Nichols; Guisselle Salazar; Mela Seyoum; Joe Sison; Manyi Tang; Kate Trout; Erin Vinson; and Cathy Zhang.

–David Dunham

My fifth year at OHC was the busiest yet! I’m especially grateful for exceptional and collaborative colleagues at OHC. This past year, we curated our first oral-history-focused gallery exhibit with videos and a podcast; we promoted our innovative Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives project, including graphic art and a superlative podcast; and we continued conducting and publishing outstanding oral history interviews. I’m also grateful that our new colleague, Liz, joined the OHC team. I hope you and yours celebrate all that’s good at the end of this year, and that next year is even better.

–Roger Eardley-Pryor

What a year 2023 has been! While I’ve had the privilege of working on several projects this past year, I’m very proud of working with Roger Eardley-Pryor and Amanda Tewes on the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives project, which launched in November. We interviewed 23 survivors and descendants of WWII-era site of Japanese American incarceration, and produced a podcast and commissioned an artist to make graphic illustrations based on these oral histories. It’s been an extremely meaningful project to be a part of, and I’m grateful for the collaborative efforts of my colleagues to bring it to fruition.

–Shanna Farrell

Looking back on the year of 2023, I am struck by the power of collaboration. This year the Oral History Center curated the multimedia exhibit, Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism, at The Bancroft Gallery, a collaborative effort that was beyond rewarding. I am extremely grateful for the opportunity to do this work and collaborate with an amazing cast of colleagues.

–Todd Holmes

I look forward every year to this opportunity to acknowledge the talented team of student editors that make the pace of our work possible. They do the work of professional editors, create abstracts for oral histories with missing metadata, write articles about our narrators and projects, and provide invaluable suggestions in our department’s quest for continuous improvement of our workflow and processes. We said farewell to some long-term employees who recently graduated: Mollie Appel-Turner, William Cooke, Adam Hagen, Serena Ingalls, and Shannon White; I’d like to say thank you to our ongoing editor, Timothy Yue; and welcome two new staff, Nikhil Jagota and Lauren von Aspen. My favorite memory from 2023 was learning about how the experience of working with oral history has had a profound impact on how our student employees see things. I hope you will enjoy reading about their reflections as much as I did in this article, Connection, Insight, Inspiration, Truth: Berkeley undergraduates reflect on oral history.

–Jill Schlessinger

This past year has been a wild ride! I said goodbye to multi-year projects, moved across the country, and started a position at the Oral History Center in October. Although it’s only been a few months, I’ve already learned much in my new role, including technical details like how to use video recording equipment and more broadly about UC Berkeley and the surrounding area. As with any big change, sometimes I feel overwhelmed with the new-ness of it all. But change brings opportunity! I’m grateful for the chance to forge a new path as an interviewer and historian here at the Oral History Center and am excited to discover what the upcoming year holds.

–Liz Semler

In November 2023, I was honored to be a part of a great team (along with Roger Eardley-Pryor and Shanna Farrell) that launched the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, featuring 100 hours of oral history interviews with 23 Japanese American narrators who are survivors and descendants of two World War II-era sites of incarceration: Manzanar in California and Topaz in Utah. This public launch highlighted the release of most of the 23 oral history interviews, a four-part podcast series based on these original interviews, and graphic art inspired by the stories and themes from the interviews. It has truly been a meaningful experience to be a part of such important work about intergenerational memory and healing. Many thanks to the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant for funding this phase of the project!

–Amanda Tewes

The OHC Welcomes Liz Semler

The Oral History Center is pleased to welcome Liz Semler, our new historian of science, medicine, and technology!

Liz comes to the UC Berkeley Library from the University of Minnesota’s Program in the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine. Elizabeth Semler is a medical and business historian and received her PhD from the University of Minnesota’s Program in the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine, where her academic work focused on the relationship between chronic diseases and diet in the United States and the Nordic countries. Her dissertation interrogated the intersections of epidemiological research, American business interests, and the development of public health prevention policies in the twentieth century. During her time at the University of Minnesota, Elizabeth taught undergraduate and community education courses on medical and technological history. She also participated in numerous public-facing history projects, including museum exhibits, educational websites, and film documentaries. Taken together, this work has fed Elizabeth’s passion for collecting, preserving, and making history accessible to broad audiences.

We sat down with Liz for a Q&A to get to know her better, which is below.

Q: When did you first encounter oral history?

A: I first encountered oral history in the first year of graduate school – I had the opportunity to participate in a project documenting the history of cardiovascular innovations at the University of Minnesota. This involved interviewing practicing clinicians, research scientists, and academicians about their contributions to cardiovascular care. It was a very different experience than studying archival documents and other static sources. Although I enjoy archival work, it was exciting to be able to ask questions and directly interact with narrators!

Q: What role did oral history play in your previous work?

A: I have worked on numerous public history projects over the past decade that have contained oral history components, with topics ranging from medical to the history of computing. Oral histories were also an important component of my dissertation project, which focused on the relationship between coronary heart disease and diet in the mid-to-late twentieth century.

Q: Which interviewers have been your biggest influences, oral historians or otherwise?

A: I really enjoy listening to Anna Sale’s interview podcast Death, Sex & Money. She does a great job of discussing challenging subjects with folks and I have learned a lot about how to tackle difficult, sensitive topics from listening to those conversations. I just learned the podcast may end in December, 2023. Who knows what will happen to archived episodes, so I recommend people give it a listen while they can!

Q: What projects are you most excited to work on at the OHC?

A: I’m still in the process of familiarizing myself with upcoming projects at OHC but I’m already very excited by the resources here at University of California, Berkeley as well as in the broader UC system. As a medical historian, the collections at UCSF have grabbed my attention – I’m looking forward to building connections across campuses and, hopefully, bringing together the resources of the Bay Area in collaborative projects.

Q: What is your dream oral history project?

A: Before COVID-19 shuttered things in 2020, I was in the process of interviewing folks who had worked at the midwest-based supercomputer company Cray Research. The company’s history is really interesting but extant archival materials are minimal and little has been written about Cray from an historical perspective. I’d like to finish capturing people’s experiences at Cray, if possible!

Welcome, Liz!

OHC URAP Student Zachary Matsumoto Reflects on Work with Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project

Zachary Matsumoto is a sophomore at UC Berkeley currently studying History and participating as an Oral History Center URAP apprentice. He was drawn to the Oral History Center after attending a Bancroft Roundtable presentation about the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project. American history is a current academic interest of his, including the histories of communities relating to his background as a Chinese and Japanese American. In his free time, Zachary likes to go for runs, watch sports, and play taiko.

Reflections on Work with the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project

by Zachary Matsumoto

This fall of 2023, I became a URAP student at the Oral History Center under the guidance of Shanna Farrell, Amanda Tewes, and Roger Eardley-Pryor. My work throughout this semester largely consisted of researching, analyzing, and writing about the oral histories of the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project, as well as the Japanese American Confinement Sites Project. These oral histories highlighted a historical event that greatly affected my own family.

In 1942, the United States government, at the beginning of its involvement in World War II, issued Executive Order 9066. This order imprisoned Japanese Americans living on the West Coast and placed them in remote prison camps across the country. My paternal grandparents and their families were among them. Growing up, my parents told me of my grandparents’ histories as incarcerees, stressing the wrongdoing and unfairness done to them by the US government. As I grew up reading and watching material on Japanese American incarceration, I began to understand the details of the incarceration experience: how truly unfair it was; the crippling effects of losing a home for a remote prison camp; the silence of incarcerees afterward; and how themes of incarceration endure today.

Fast forward to 2023, when I joined the OHC as a URAP student and explored the oral histories of Japanese Americans. One component I learned from these oral histories was the traumatic intergenerational effects of incarceration: the pain and guilt that incarcerees passed down to their children, and at times even their grandchildren. This was a very eye-opening experience for me, as I personally felt as if the incarceration of Japanese Americans was an important, but almost distant historical event in my own life. Reading these oral histories, as well as listening to a podcast series “From Generation to Generation: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration,” based on the very same interviews, was at times an emotional experience. Hearing of descendants losing their sense of belonging, feeling disconnected with their culture, and living without the knowledge of their families’ incarceration experiences was heartbreaking to hear.

But what really struck me about these oral histories was not only the intergenerational pain and sorrow, but the agency exhibited by the project narrators after incarceration. This is something I knew but not really understood the scope of. This agency, as recounted in the oral histories, was both public and private. Patrick Hayashi, a man born in the incarceration camps and whose oral history I studied extensively, demonstrated activism as one of California’s first Asian American Studies professors and by fighting against prejudiced admissions practices. But more privately, he vowed to reexamine the trauma of his family’s past through creating artwork and educating Utah teachers on incarceration. Other individuals, in the 1970s and 1980s, participated in the redress movement, in which Japanese Americans questioned the wrongdoing of WWII incarceration and successfully drew attention to this experience. This eventually led to a formal apology and reparations paid by the US government.

Even in more recent years, the agency and activism of individuals in the oral history interviews shines brightly. Ruth Sasaki, an author, joined an organization named Tsuru for Solidarity: a group that fought against the forced incarceration of migrants crossing the US-Mexico border. After the Trump administration detained migrants at the US-Mexico border, including children, as part of the Zero Tolerance Policy, Sasaki and twenty-six other Tsuru for Solidarity members flew to Oklahoma to protest, along with a large number of Native American, Latino, and African American activists. Sasaki’s story, in particular, served as a reminder for me of the living memory of Japanese American incarceration and how that community in particular could serve as a key fighter: a guard against the unjust, unprovoked incarceration of marginalized groups today.

One moment of agency, in particular, was very personal for me and my interests. Roy Hirabayashi, a longtime San Jose resident and the descendant of Topaz survivors, recalled the founding of San Jose Taiko, a taiko (Japanese drumming) performance group. As San Jose Taiko began its performances and found its sound and style, Hirabayashi realized he did not know many traditional Japanese themes and rhythms for playing taiko; instead, he took rhythmic inspiration from music he was exposed to in the Bay Area, such as R&B and Latin soul. According to Hirabayashi, “We felt we were establishing pretty much early on that we, in Asian American sound, using what we called the Japanese drum, the taiko, our version.” For Hirabayashi, taiko was not just a performance instrument but an intentional expression of his developing Asian American identity. This, to me, shows his agency and sense of self. Reading Hirabayashi’s oral history also highlighted my personal connection to this interview. As a child, my mom drove me forty minutes to Santa Rosa so I could learn and practice taiko. Now, as a sophomore in college, I am a current member of Cal Raijin Taiko, UC Berkeley’s taiko organization and performance group. The fact that an instrument that occupies an important place in my own life is wrapped in the history and agency of Japanese Americans captivates me and brings me closer to the history of the Japanese American experience.

Over the course of my URAP experience in the Oral History Center, I felt my eyes further opened to the individual experiences of the descendants of incarcerees. What stands out was not just their guilt and attempts to cope with the scars of incarceration, but instead their strength through identity and activism. As a Japanese American myself, I feel proud to be part of this legacy of strength. In the future, I hope to continue exploring my identity, and what it means to be a descendant of the incarceration camps. As I explored the oral histories in the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project, I encountered personal questions: why am I not feeling the same burden as the descendants of incarceration? Why do I feel as if incarceration was a memory without a strong effect on my own life? These questions remain in my mind, and I will continue to seek answers to them throughout my life.

OHC Exhibit “Voices for the Environment” Curator Q&A

The Oral History Center is excited to announce the opening of Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism, a Bancroft Library Gallery exhibition that was curated by Todd Holmes, Roger Eardley-Pryor, and Paul Burnett. Voices for the Environment traces the evolution of environmentalism in the San Francisco Bay Area across the twentieth century. In three sections, it highlights how Bay Area activists have long been on the front lines of environmental change—from efforts to preserve natural spaces in the wake of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, to the midcentury fight for state regulations to protect San Francisco Bay shoreline, to more recent demands for environmental justice to address the disproportionate burden of pollution that sickened communities of color around the Bay.

We sat down with Eardley-Pryor and Holmes to ask them about their experience curating the exhibit, bringing the OHC’s interviews to life in The Bancroft Library’s gallery, and what they learned along the way.

Q: When you were originally thinking about this exhibit, which spans a century of Bay Area environmental activism, what topics, themes, or events were important for you to include?

TH: As historians, both Roger and I approached the exhibit through the lens of change over time, essentially asking the question, “How did what we’ve come to recognize as environmentalism evolve and change in the Bay Area over the twentieth century?” Combining our knowledge of both the oral history collection – which was to stand at the heart of the exhibit – and the environmental history of California, we selected the three stories we wanted to highlight fairly quickly.

First, we wanted to tell the story of Hetch Hetchy, the valley in Yosemite National Park that was dammed for San Francisco’s water system. This is a seminal event used in history classes across the nation to highlight the battle between two schools of environmentalism, preservationists like the Sierra Club’s John Muir, and conservationists like Gifford Pinchot of the U.S. Forest Service in the first part of the twentieth century. For the exhibit, we sought to use the Hetch Hetchy story to introduce visitors to preservation as the first form of environmentalism that took root in the Bay Area.

Second, we wanted to tell the story of Save The Bay, the movement initiated by three women from Berkeley to halt bay fill. Ultimately, that movement led to the creation of the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC), a state government agency to regulate development on the bay. Here we wanted to highlight how environmental concerns became embedded within the fold of government by the mid-century. BCDC stands as the first environmental agency in the United States, providing a precedent for other regulatory agencies on the state and federal level in the years that followed, such as the California Coastal Commission. Moreover, BCDC also operated within a framework that sought to balance environmental protection with economic development.

Third, we wanted to tell the story of environmental justice, a movement in the last part of the twentieth century that sought to put the health of people – particularly communities of color – within the environmental agenda. While environmental justice is fairly common today in discussions of environmental policy, the story of how it developed is not well known, and the Bay Area was one of the central places in the nation from which the movement took root.

REP: Todd and I worked to ensure that, in this exhibit, environmental activists could speak for themselves, and that visitors to the exhibit could actually hear the voices of activists recorded in their oral history interviews. The Audio Spotlight technology that allow people to hear interview clips in the gallery, the three videos Todd created with rare film footage and photographs, and the three podcast episodes we made with Sasha Khokha of KQED all make this exhibit something special that has never been done before in The Bancroft Library Gallery. For me, the people-power of communities of color demanding environmental justice, and the longtime leadership of women working for environmental protection were really important themes to include. Often, environmental history is told through the actions of men like John Muir, who does deserve credit for his early advocacy to protect nature through its preservation. The legacy of Muir and the ongoing work of the Sierra Club are important, and they remain so today. But Todd and I wanted to tell a deeper and broader history of Bay Area environmentalism, which shows how women and people of color have been central to the expansion and the evolution of environmental action over the course of the 20th century. I hope the stories shared in this exhibit help contextualize and make current environmental issues more meaningful—be it present-day preservation issues in 30 x ’30 campaigns, or conflicts over coastal regulations amid sea-level rise, or ongoing challenges to empower people of color in mainstream environmental movements.

Q: Did the themes you wanted to highlight change during the course of your research?

REP: We worked hard for over a year to bring this exhibit to life and to my memory, we agreed fairly early on about the three main narratives featured in the exhibit—the preservation of nature, reconciling environment and development, and environmental justice for communities of color. Over the course of our research, we changed the details of which particular oral history segment we might include here or there, or which image or document would best compliment the oral histories featured in each section of the exhibit. But as I recall, the exhibit’s main story arc remained steady from early in our curation process.

TH: Surprisingly, there was no change in the main topics / stories we wanted to highlight in the three sections of the exhibit. What our research did do was help expand on the themes within each to add more depth and nuance around community activism. For instance, in the first section we not only focused on the story of Hetch Hetchy, but connected it to activism around Save the Redwoods, which in turn highlighted the vital – yet often overlooked – role of women in the early preservation movement. Men like John Muir may have become the figureheads of environmentalism, and voted for such policies in government, but it was women who provided the grassroots momentum that put environmental concerns on the table. The same could be said for the third section on environmental justice. Our research uncovered a lot of different groups and experiences in the Bay Area grappling with environmental racism, from toxic sites in Richmond and what became known as the Silicon Valley, to debates with white environmental groups about even using the term “racism.” So in all, our research gave us a number of themes to spotlight and weave together throughout the exhibit

Q: The exhibit begins with the 1906 earthquake. Why did you decide to start there?

TH: This is another example of how research expanded the themes and stories of the three main topics we sought to feature in the exhibit. We wanted to highlight the story of Hetch Hetchy in the first section. Our research of the Hetch Hetchy battle forced us to upstream to the root cause – the 1906 earthquake and fire that destroyed 80 percent of San Francisco. At the time, San Francisco stood as the largest and richest city west of Chicago. In the wake of the disaster, the rebuilding effort posed a tremendous threat to the natural resources of the state. Ancient redwood forests throughout the Bay Area and along California’s north and central coast were targeted for timber, just as the Hetch Hetchy Valley was eyed for water and hydro-electric power. Thus, these rebuilding efforts proved the impetus of the early activism to preserve California’s environment.

REP: The drowning of Hetch Hetchy Valley—despite it being located within Yosemite National Park—is such a powerful and classic story in environmental history, and it occurred because the 1906 earthquake and fire destroyed San Francisco. Amazingly, Todd found several oral histories in our collection with survivors of the earthquake and fire who recall their experiences of it when they were children. In The Bancroft Library, Todd also found historic film footage, recently digitized, that shows San Francisco still aflame just after the earthquake. Putting those oral histories together with this footage make for a captivating start to the exhibit.

But what I didn’t realize until working on the exhibit was how the preservation of redwoods was also connected to how the earthquake and fire destroyed San Francisco. After the fire, lumber companies promoted California’s fire-resistant coastal redwoods as a means to rebuild the devastated city. In turn, environmentalists redoubled their efforts to preserve special groves of those ancient redwood trees. It suddenly made sense to me how Muir Woods National Monument was established in Marin County just a few years after the 1906 earthquake. Additionally, we wanted our exhibit on Bay Area environmentalism to highlight the Sierra Club, which was founded in San Francisco in 1892 and has since become one of the most influential environmental organizations in the nation. The Oral History Center has conducted oral histories with Sierra Club leaders since the early 1970s, and several activists, like William Colby, Ansel Adams, and David Brower, discussed in their oral histories how the fate of Hetch Hetchy continues to inform ongoing preservation efforts. So, in many ways, the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire helped ignite the spirit of preservation that still informs environmental activism, both in the Bay Area and across much of North America.

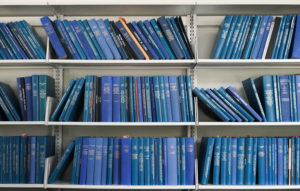

Q: What role does oral history play in the exhibit?

REP: Oral history is the beating heart that gives life to this exhibit! We scoured several scores of Oral History Center transcripts for captivating stories about Bay Area environmental activism. David Dunham helped us obtain digitized versions of those oral history recordings. We then used The Bancroft’s traditional paper, photograph, and film collections to complement the oral history narratives that we featured in the exhibit. Christine Hult-Lewis and Lorna Kirwan helped us explore several of those archival collections, and Theresa Salazar pointed us to the excellent Urban Habitat Program Records, 1970-2001, which are displayed in our exhibit. Ultimately, the exhibit offers a multi-sensory experience where visitors can engage audio recordings, film footage, oil paintings, photographs, pamphlets, posters, descriptive text, and they can even hold the hardbound oral history transcripts featured in the exhibit. But certainly, oral history is the centerpiece of the exhibit.

TH: In short, everything! This is the first exhibit curated by the Oral History Center, and the first in-depth effort to showcase both the oral history and other archival collections of The Bancroft Library. Each section features oral histories about the main topic in three ways. Edited oral history segments are played in each section through an Audio Spotlight speaker, and accompanied with a video that shows captions as well as related photographs and archival footage. The oral histories are also available through a three-episode podcast, narrated by Sasha Khokha from KQED San Francisco. The podcast episodes, available online and in the gallery by scanning a QR Code, offer a deeper dive into the stories of each section. Lastly, we used oral histories quotes in the labels of the exhibit material to add further detail and context.

Q: The 1960s and ’70s were two very productive decades in terms of environmental activism. Did the oral histories that you encountered from the OHC’s collection make you think differently about this period, or illuminate something new?

TH: In my view, the oral histories we used in the exhibit helped place the activism of the 1960s and 1970s in better context. For instance, we often think of the “environmental movement” as arising around the late 1960s / early 1970s. Yet, this view completely overlooks the activism of men and women around preservation in the first couple decades of the twentieth century. It also overlooks the vital work of Sierra Club executive director David Brower, whose activism throughout the 1950s and 1960s staved off numerous developments and led to the establishment of ten new national parks. In many respects, I think the oral histories featured in this exhibit pushed me to think about a “long environmental movement” that gained traction in the halls of government during the 1960s and 1970s. I think the exhibit also highlights how the Civil Rights Movement and environmental movement came to intertwine by the end of the decade to form environmental justice, which was an area I felt fortunate to learn more about through this project.

REP: Actually, rather than the 1960s and 1970s, the oral histories we included in the exhibit helped me realize the importance of the 1980s and 90s to the expansion and evolution of environmentalism. Without a doubt, activity surrounding Earth Day in 1970 was a key inflection point in environmental history, inspiring new environmental laws and a new generation of environmental activists. But the oral histories in our exhibit tell how Bay Area activists laid the early groundwork at least since the early 20th century for later environmental regulations, and how activists in the final decades of the 20th century worked to include all people in environmental protections, especially communities of color who suffered the most from industrial pollution.

Q: You put together additional material, like a podcast and class workbook, to accompany the exhibit. How do you hope people will use these materials?

TH: For the past couple years, the Oral History Center has been working on ways to get our collection into the K-12 education space. We developed additional materials, such as the class workbook and podcast, to serve as educational resources for K-12 classrooms, as well as undergraduate courses.

REP: The podcasts and educational workbook can be used anywhere—while visiting and experiencing the exhibit in person, or at home or in classrooms. We hope people use those additional materials long after the exhibit closes in November 2024!

Q: What do you hope that people take away from the exhibit?

REP: I hope exhibit visitors sense the importance, power, and potential of oral history. I hope they see how the Oral History Center’s work to record the lived experiences and reflections of people through oral history creates invaluable records that helps us better understand where we’ve come from and helps us make sense of our experiences today. I also hope visitors realize the importance of Bay Area activists in shaping the evolution of environmentalism over time. And I hope visitors hear how the actions of Bay Area people in the past, as told in their own words, helped define our experiences in the Bay Area today. Given today’s grave threats to our environment and to our democracy, I hope visitors appreciate how environmental activism remains an ongoing process that is shaped and renewed by average people like them who engage in civic activism. I also hope the oral histories featured in this exhibit—and the many, many more that are preserved in the Oral History Center collection—help inspire people to shape and renew environmentalism today and in the future.

TH: I hope visitors come away from the exhibit with a better understanding of how environmentalism evolved and changed over the century, and that it has a long history in the Bay Area. Moreover, I hope the oral histories featured in the exhibit highlight the change brought on by everyday people. It was the activism of men and women that led to protected redwood forests and the creation of state and national parks. It was the unwavering dedication of three women from Berkeley that stopped fill projects in San Francisco Bay and led to the nation’s first government-run environmental agency. And it was the collective action of communities of color that put justice within the environmental agenda, and on the dockets of policymakers. Ultimately, I hope visitors, young and old, walk away with the idea that change comes about through everyday people.

“Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism,” an Oral History Center exhibit in The Bancroft Library Gallery

We’re excited to announce the opening of Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism, a Bancroft Library Gallery exhibition that was curated by Todd Holmes, Roger Eardley-Pryor, and Paul Burnett of the Oral History Center. Voices for the Environment traces the evolution of environmentalism in the San Francisco Bay Area across the twentieth century. In three sections, it highlights how Bay Area activists have long been on the front lines of environmental change—from efforts to preserve natural spaces in the wake of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, to the midcentury fight for state regulations to protect San Francisco Bay shoreline, to more recent demands for environmental justice to address the disproportionate burden of pollution that sickened communities of color around the Bay.

Our Voices for the Environment exhibit is the first major effort in The Bancroft Library Gallery to showcase oral history alongside the traditional archival collections of The Bancroft Library, with the oral history collections leading the way. The exhibit still features historic photographs, pamphlets, post cards, and posters selected from several collections of The Bancroft’s physical archives. But for the first time in this gallery, our Voices for the Environment exhibit also includes three installations of special Audio Spotlight technology where you can listen to never-before-heard oral history recordings with Bay Area environmentalists, while simultaneously watching three videos edited by Todd Holmes that feature historic photographs and rare film footage from The Bancroft’s digital collections. Additionally, as a complement to the exhibit, curators Todd Holmes and Roger Eardley-Pryor created an educational workbook, so students of all ages can learn about the environmental movement by engaging with the themes and primary sources on display. Through these efforts, the Oral History Center hopes Voices for the Environment will have a life beyond its yearlong run.

For an even deeper dive, you can also scan a QR code in the gallery, or click the following link, to hear three Voices for the Environment podcast episodes produced in partnership with Sasha Khokha of KQED Public Radio and The California Report Magazine. The podcast episode for section 1 of the exhibit, titled “A Preservationist Spirit,” traces the environmental activism that arose amid the rebuilding efforts of San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake and fire, efforts that came to target the state’s ancient redwood forests and the beloved Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park. The episode features historic interviews from the Oral History Center archives including segments from the “Growing Up in the Cities” collection recorded in the late 1970s by Frederick M. Wirt, as well as oral history interviews with Carolyn Merchant recorded in 2022, with Ansel Adams recorded in the mid-1970s, and with David Brower recorded in the mid-1970s. The oral history of William E. Colby from 1953 was voiced by Anders Hauge, and the oral history of Francis Farquhar from 1958 was voiced by Ross Bradford. This first episode also features audio from the film Two Yosemites, directed and narrated by David Brower in 1955. The podcast episode for section 2 of the exhibit, titled “Tides of Conservation,” tells the story of the Save San Francisco Bay movement and the creation of the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC), one the nation’s first environmental regulatory agencies. The episode features segments from oral history interviews with Save The Bay founders Esther Gulick, Catherine “Kay” Kerr, and Sylvia McLaughlin recorded in 1985; as well as interviews with BCDC executive director Joseph Bodovitz and chairman Melvin B. Lane, both recorded in 1984. And the podcast episode for section 3 of the exhibit, titled “Environmental Justice for All,” spotlights efforts by communities of color to place the health of people within the environmental agenda, including creation of new environmental organizations like the West County Toxics Coalition, the Urban Habitat Program, and APEN (Asian Pacific Environmental Network), all founded in the Bay Area. The episode features segments from oral history interviews with Carl Anthony, Pamela Tau Lee, Henry Clark, and Ahmadia Thomas, all recorded in 1999 and 2000.

The Voices for the Environment exhibition space was designed by Gordon Chun and is free and open to the public Monday through Friday between 10am to 4pm from Oct. 6, 2023 to Nov. 15, 2024, in The Bancroft Library Gallery, located just inside the east entrance of The Bancroft Library.

We hope you come to campus and experience it!

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. While we receive modest institutional support, we are a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. We must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

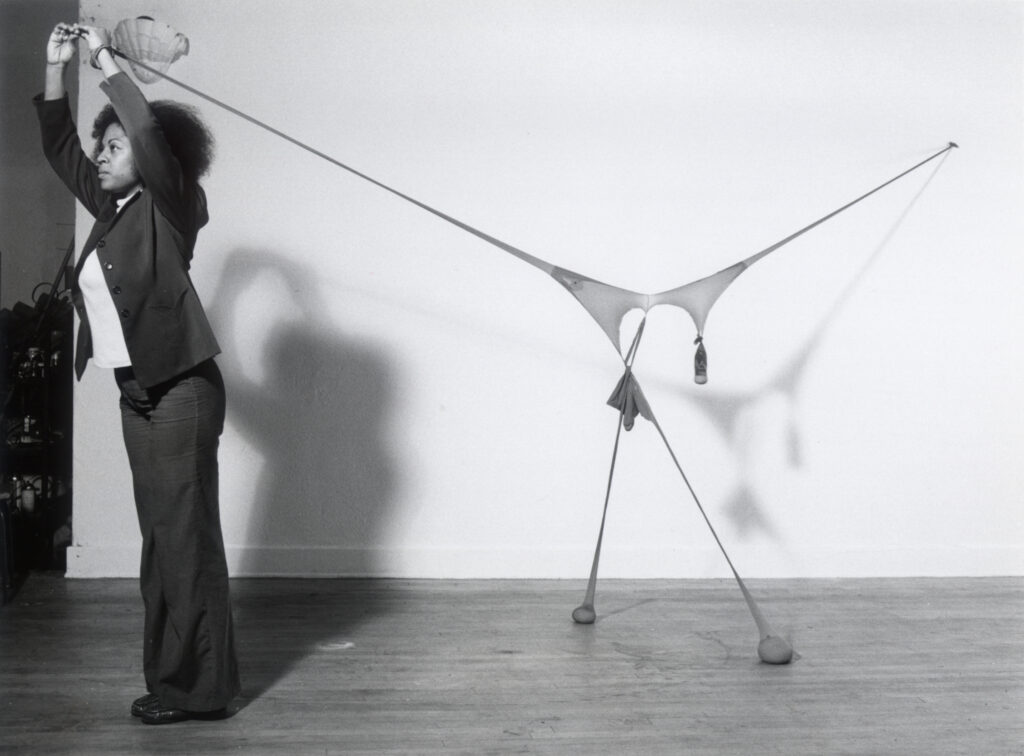

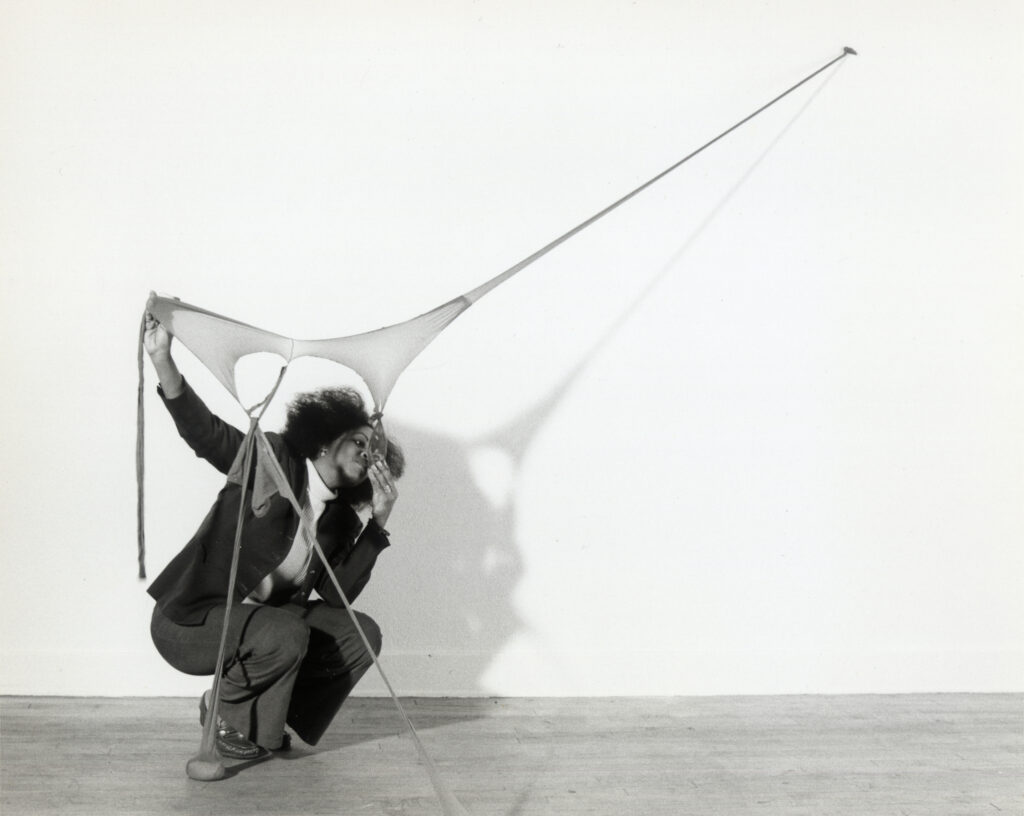

Senga Nengudi: Black Avant-Garde Visual and Performance Artist

As a continuation of our work for the Getty Research Institute’s African American Art History Initiative (AAAHI), Dr. Bridget Cooks and I conducted several oral history interviews with the avant-garde artist Senga Nengudi. This interview is one of several AAAHI oral histories exploring the lives and work of Los Angeles-based artists, and highlights Nengudi’s contributions to visual and performance art.

Senga Nengudi is an avant-garde artist best known for her abstract sculpture and performance art. Nengudi was born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1943 and moved to Los Angeles, California, at a young age. She attended California State University, Los Angeles (CSULA) for both her undergraduate and master’s work, as well as completed a program at Waseda University in Tokyo, Japan. Nengudi was active in the avant-garde Black art scenes in Los Angeles and New York during the 1960s and 1970s, and was a member of the Studio Z Collective. She is best known for her R.S.V.P. (Répondez s’il vous plaît) Series featuring pantyhose, which she began in 1975. Nengudi is the recipient of many awards, including the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Award in 2005, the Anonymous Was a Woman Award in 2005, the Denver Art Museum Key Award in 2019, and was elected as a member to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2020. Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Senga Nengudi was still in elementary school when she and her mother moved to Los Angeles in the early 1950s. Despite a brief stint in New York, for more than thirty years she lived in the greater Los Angeles area first as a child; as a student at CSULA; as an artist and active member of the Studio Z Collection; and as a young mother. That Nengudi called Los Angeles home for so long meant that her formative years of creative expression and early artistic networks sprang from the Southland.

Looking back, Nengudi credits her mother with providing a creative foundation.

“…she was very, very, very conscious of the home and making something home, and so she would decorate the house. And then, say like three years later, she would repaint the walls, she would change the upholstery, she would do all those kinds of things. She was very aesthetically aware, as well as needed a particular beauty in her home to feel good.”

And Nengudi expressed her own creativity through several outlets, remembering, “It’s always been a deal between art and dance with me…” Indeed, during her undergraduate years at CSULA, she chose to major in art and minor in dance—a pairing which supports much of her work.

In the mid-1970s, Nengudi found an outlet to express her love of performance through the Studio Z Collective—a collective of artists interested in improvisation that continued into the 1980s. In addition to Nengudi, Studio Z was comprised of Houston Conwill, David Hammons, Maren Hassinger, and occasionally other artists including Franklin Parker and Ulysses Jenkins. Her relationships with these artists also had a great impact on Nengudi’s artistic career. Thinking of Studio Z’s contribution to her 1978 performance Ceremony for Freeway Fets, which took place under a freeway overpass on Pico Blvd., she muses that “we all kind of supported each other in our efforts.”

Nengudi also found early support from Los Angeles-based gallery owners like Greg Pitts at the Pearl C. Woods Gallery, as well as Brockman Gallery’s Alonzo and Dale Davis. In fact, Brockman Gallery’s dispersal of CETA [Comprehensive Employment and Training Act] funds helped employ artists like Nengudi and Maren Hassinger.

Hassinger remains Nengudi’s longtime creative collaborator. Nengudi recalls that the connection between the two was immediate, “We just kind of instantly became friends, because there was this commonality. She was involved with dance, she was involved with sculpture, all that kind of stuff.” And to why this collaboration with Hassinger has sustained both the passing of years and geographical distance, Nengudi explains:

“Because we believe so much in collaboration. We believe in unity. We believe in bringing the best out in each other…Even though our background is different, our interests are the same. It’s always been dance, performance, sculpture, movement, and this commitment to our art. And when we had some really funky times and we were 2,000 miles apart, the thing that held us together was this commitment to art. And so that kind of carried us through the most difficult things…So all these life events were going on, but the constant was our ability to connect and think and make happen.”

Nengudi’s most recognizable series of work is R.S.V.P., which she started in the mid-1970s. The R.S.V.P. Series, or Répondez s’il vous plaît (respond, please), demonstrated Nengudi’s experimentation with nylon pantyhose. Importantly, Nengudi began working in this medium after the birth of her first son, when she was especially interested in the elastic nature of a woman’s body. She recalls,

“So yes, the explorations were really exciting. I put eggs in them, I broke eggs in them…I used white glue, I used hot glue, which obviously didn’t last that long. I tried everything—resin. Again, it dissolved in the resin. So really, as I was developing the series, it was all about exploring the material…And it took a while to get to…the sand, where I just noticed that…once in the nylons, it had such sensuality to it, because it had this kind of natural body form from the weight of the sand.”

Given the experimental nature of her sand-filled nylon pieces, Nengudi explains, “I thought about them as sculpture first. I did not develop them thinking that I would perform in them.” But Nengudi eventually did embrace the performative potential of these sculptures, even engaging Hassinger to perform with them at the Pearl C. Woods Gallery in 1977 by entwining her body with the material, manipulating it, even dancing with it.

Nengudi has lived in Colorado since the 1980s, and continues to stimulate audiences by creating work that plays with the line between sculpture, installation, and performance in space. However, she has also made significant contributions as an arts educator, especially at University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, and as an advocate of the arts. Namely, she established a community art gallery called ARTSpace in Colorado Springs so that “artists could show their work” and learn “what it takes to have an art exhibit.” The added bonus, of course, was that “the community could come in and see the artwork. It was right there for them.” For someone whose early exposure to creative expression was so formative to her artistic practice, this is a logical next step to engage new generations of artists and viewers. It also connects with her decades-long entreaty to audiences: “respond, please.”

To learn more about Senga Nengudi’s life and work, check out her oral history interview! Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Oral History Center Celebrates “Graduates”

Spring is a time of year when things begin anew. Flowers bud new petals, days have new length, and college graduates embark on new careers. It’s also a time when we at the Oral History Center celebrate an exciting phase of our narrators’ lives: a new life in our archive, where their story will live on in perpetuity. Not only can a narrator’s loved ones, friends, and colleagues access their interviews for years to come, students, researchers, and scholars can learn something about a time and a place, illuminating an aspect of history they might not have previously considered.

One way the UC Berkeley Oral History Center (OHC) likes to usher in this new phase of a narrator’s life is to have a “graduation” ceremony to honor their participation in the oral history process. Traditionally, we did this in person at the Morrison Library here on UC Berkeley’s campus, but like many things, we’ve had to adjust in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, we like to list their names and the projects for which they were interviewed online and in our newsletter so that all those in the OHC’s community can celebrate their contributions with us from near and far.

Please join us in expressing our appreciation for our latest cohort of narrators, spanning from fall 2021 to spring 2023. We are grateful to have their voices in our collection and their stories a new part of the historical record.

We also want to thank the OHC team—Paul Burnett, David Dunham, Roger Eardley-Pryor, Shanna Farrell, Todd Holmes, Jill Schlessinger, and Amanda Tewes—for their work in making these interviews come to fruition, along with the support from our student employees, who are a valuable part of our process: Max Afifi, Mollie Appel-Turner, Hue Bui, Mina Choi, William Cooke, Georgia Cutter, Nikki Do, Adam Hagen, Jordan Harris, Vivien Huerta-Guimont, Ashley Sangyou Kim, Ricky Noel, Deborah Qu, Mela Seyoum, Lauren Sheehan-Clark, Joe Sison, Erin Vinson, Shannon White, Serena Williams, and Timothy Yue.

Bravo, Oral History Center Class of 2023!

Anchor Brewing Co.

Mark Carpenter

Gordon MacDermott

Fritz Maytag

Linda Rowe

Bay Area Women in Politics

Louise Renne

Ruth Rosen

J.J. Wilson

California Business

Fred Martin

California Cannabis

Oliver Bates

California State Archives State Government Oral History Program

Wesley Chesbro

Fran Pavley

Lois Wolk

Bill Lockyer

Chicana/o Studies

Adele de la Torre

Ignacio García

East Bay Regional Park District

Ira Bletz

Ginny Fereira

Neil Havlik

Carol Johnson

Doug McConnell

Ruth Orta

Bethia Stone

Jeff Wilson

Mark Taylor

Mae Torlakson

Tom Torlakson

Will Travis

Nancy Wenninger

Environment/Natural Resources

Mary D. Nichols

Getty Research Institute’s African American Art History Initiative

Marion Epting

Maren Hassinger

Leslie King-Hammond

Thaddeus Mosley

Sylvia Snowden

William T. Williams

Vickie Wilson

Richard Wyatt

Getty Trust

Jerry Podany

Uta Barth

Tobey Moss

Katrin Henkel

Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives

Miko Charbonneau

Bruce Embrey

Hans Goto

Patrick Hayashi

Jean Hibino

Mitchell Higa

Roy Hirabayashi

Carolyn Iyoya Irving

Susan Kitazawa

Naomi Kubota Lee

Ron Kuramoto

Jennifer Mariko Neuwalder

Kimi Maru

Lori Matsumura

Alan Miyatake

Margret Mukai

Ruth Sasaki

Steven Shigeto Sindlinger

Masako Takahashi

Peggy Takahashi

Nancy Ukai

Hanako Wakatsuki-Chong

Rev. Michael Yoshii

Moore Foundation

Edward Penhoet

Kenneth Siebel

James C. Gaither

National Park Conservancy

Greg Moore

Sierra Club

Rhonda Anderson

Bruce Nilles

Verena Owen

Rita Harris

Resources and Planning

Anders Hauge

San Francisco Politics

Norman Yee

University History

Doris Sloan

Carolyn Merchant

Randy H. Katz