By Shannon White, with research by Adam Hagen

Loyalty oaths have long been in use in the United States as a means of promoting social unity in the face of war, perceived security threats, or fears about waning political support. Even now, loyalty oaths are common as a condition of employment for many state workers. In fact, all employees of the state of California, including the faculty and staff members of the University of California, currently sign an oath of loyalty upon hire, stating that they will defend the constitution against all enemies foreign and domestic, and that they take this obligation freely.

In particular, the idea of a governmental loyalty oath rose to prominence in the 1940s, when tensions between the US and the Soviet Union and growing fears about a communist infiltration of the government prompted President Harry S. Truman to establish a loyalty program for federal employees. In March 1947, Truman signed Executive Order 9835, which ensured that employees of the US government could be subject to investigation for potential involvement in “subversive” organizations.

In the wake of President Truman’s Executive Order, the California state legislature began to introduce its own policies in opposition to potential communist activity in the government. These proposals would have given the state authority over the University of California in matters of loyalty, prompting the University of California administration to act in response to prevent infringement on the institution’s autonomy. Furthermore, the university was at this time also facing financial difficulties, with the state threatening to withhold funding for the university budget due to worries about subversive activity within its community. As a result of these mounting pressures, University President Robert G. Sproul proposed his own loyalty oath for university faculty and employees on March 25, 1949. The text of the oath approved by the Regents on June 24 was as follows:

In the wake of President Truman’s Executive Order, the California state legislature began to introduce its own policies in opposition to potential communist activity in the government. These proposals would have given the state authority over the University of California in matters of loyalty, prompting the University of California administration to act in response to prevent infringement on the institution’s autonomy. Furthermore, the university was at this time also facing financial difficulties, with the state threatening to withhold funding for the university budget due to worries about subversive activity within its community. As a result of these mounting pressures, University President Robert G. Sproul proposed his own loyalty oath for university faculty and employees on March 25, 1949. The text of the oath approved by the Regents on June 24 was as follows:

I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support the Constitution of the United States and the Constitution of the State of California, and that I will faithfully discharge the duties of my office according to the best of my ability; that I do not believe in, and I am not a member of, nor do I support any party or organization that believes in, advocates, or teaches the overthrow of the United States Government, by force or by any illegal or unconstitutional means, that I am not a member of the Communist Party or under any oath or a party to any agreement or under any commitment that is in conflict with my obligations under this oath.

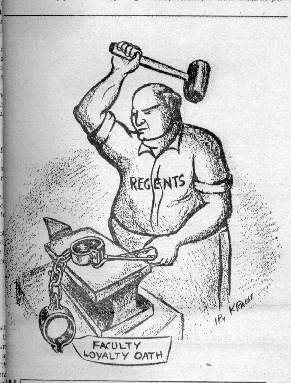

Almost immediately, the introduction of the loyalty oath garnered controversy. Many faculty members and staff refused to sign the oath, resulting in a rash of firings and resignations and a tense stand-off between the Board of Regents and university faculty, staff, and students. The oath was later declared unconstitutional in 1951 in Tolman v. Underhill, and many of the thirty-one dismissed faculty returned to Berkeley.

1950 August 25, BANC PIC 1959.010. San Francisco News-Call Bulletin Newspaper Photograph Archive, The Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley.

The UC Berkeley Oral History Center has several interviews related to the loyalty oath controversy, many from UC faculty members who witnessed or were themselves involved in the response to the oath’s introduction.

Among these is a collection of interviews specifically concerning the loyalty oath, which features oral histories from Howard Bern, a UC Berkeley faculty member who signed the oath last-minute; Ralph Giesey, a graduate student of non-signer Ernst Kantorowicz; and Deborah Tolman Whitney and Mary Tolman Kent, the children of Berkeley professor Edward Tolman, a key leader of the faculty opposition to the oath.

These interviews reveal the fraught relationship between university faculty and administration after the instatement of the loyalty oath, with rampant fears about academic freedom and discrimination against potentially “subversive” faculty members. Here, Howard Bern shares his distaste of the oath and his moral grounds for originally refusing to sign:

I felt that it was discriminatory, that it was singling out university professors as if they were especially potentially evil. So on a civil libertarian ground I objected to this. And the second ground was my own feeling. I had been in the army for almost four years. What more manifestation of loyalty did they really want?

In the oral history of Charles Muscatine, who returned to UC Berkeley in 1953 after being fired for his refusal to sign the oath as an assistant professor, Muscatine recalls the most poignant moment for him of the entire controversy:

At a certain moment, [Malcolm Davisson, a faculty policy chair] contacted me. He said, “We have lost the moral right to decide.”

Other interviews offer more insight into the experience of witnessing the loyalty oath controversy firsthand. For instance, Ralph Giesey discusses the hearings he and his fellow non-signing teaching assistants had to undergo as a condition of their opposition to the oath. Howard Schachman, an assistant professor at UC Berkeley at the time of the oath, describes the moral compromise he underwent when he signed something he considered philosophically “abhorrent.”

The loyalty oath controversy at UC Berkeley is often viewed through the perspective of academic freedom amid anticommunist fervor, but an oral history of Clark Kerr, UC Berkeley faculty member at the time — and later campus chancellor and university president — provides another perspective. Kerr observed that the controversy must be viewed in light of the internal divisions in the Board of Regents that escalated in the 1940s over debates about centralization versus campus autonomy. According to Kerr, Regent John Francis Neylan and the southern regents tended to favor campus autonomy, while University President Robert G. Sproul and most of the northern regents called for a centralized system. This issue resolved itself with the creation of the post of chancellor for each UC campus, and Kerr himself was later appointed to the position at UC Berkeley in 1952.

According to Kerr:

As I understand it, Neylan really just seized on the oath controversy as a way of whipping Sproul around because he was unhappy with him on other grounds. . . . [Sproul] looked to me like a man who was just immobilized by the controversy. It was out of this, according to what I observed, that [Earl] Warren then came to take a position of leadership, which he had not taken in the regents before. Normally governors don’t. But the controversy was tearing the university apart. The president was immobilized. Warren stepped in, then, essentially against the oath, or at least against the firing of the non-signers, and took leadership of the more liberal elements of the board.

Howard Bern also recognizes Robert Sproul’s role in mishandling the loyalty oath controversy, stating, “Just as, although he would not admit it, the Free Speech Movement really broke Clark Kerr, I think the loyalty oath situation just destroyed Robert Gordon Sproul and his influence. I don’t think he was a bad man, a bad leader, but I think he made a very fatal error.”

All in all, these oral histories concerning the UC loyalty oath controversy are a great resource for understanding the climate at the University of California in the 1940s and ’50s. They offer a wealth of insight concerning the faculty experience at UC Berkeley, and since many of the interviewees went on to become involved with the Free Speech Movement and other political causes, there is a particular focus in these oral histories on the growth of social movements at the university. For more information about the loyalty oath controversy, check out the Oral History Center’s collection of interviews concerning the oath and other related resources from The Bancroft Library.

Shannon White is currently a third-year student at UC Berkeley studying Ancient Greek and Latin. They are an undergraduate research apprentice in the Nemea Center under Professor Kim Shelton and a member of the editing staff for the Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics. Shannon works as a student editor for the Oral History Center.

Adam Hagen is currently a third-year history student with a concentration in modern European history. Adam works as a student editor for the Oral History Center. He is also a member of the editing staff of Clio’s Scroll, the Berkeley Undergraduate History Journal.

Related Resources from the OHC and The Bancroft Library

Oral Histories Cited

Clark Kerr, University of California Crises: Loyalty Oath and the Free Speech Movement.

The Loyalty Oath at the University of California, 1949–1952. Interviews with Howard Bern, Ralph Giesey, Mary Tolman Kent, Deborah Tolman Whitney.

Howard Schachman: UC Berkeley Professor of Molecular Biology: On the Loyalty Oath Controversy, The Free Speech Movement, and Freedom in Scientific Research.

Charles Muscatine: The Loyalty Oath, The Free Speech Movement, and Education Reforms at the University of California, Berkeley.

Related Oral History Projects

The SLATE Oral History Project documents the UC Berkeley campus political organization SLATE — so named because the group backed a slate of candidates who ran on a common platform for ASUC (Associated Students of the University of California) elections from 1958 to 1966. SLATE ignited a passion for politics in the face of looming McCarthyism and what many perceived as the University of California’s encroachment on student rights to free speech. See also, “They Got Woken Up”: SLATE and Women’s Activism at UC Berkeley

The Free Speech Movement Oral History Project documents the movement at UC Berkeley that began in the fall of 1964 from the perspective of the ordinary people who made it possible — and those who opposed it — including students, lawyers, faculty, and staff.

Related Resources from The Bancroft Library

Kantorowicz, Ernst H. The fundamental issue : documents and marginal notes on the University of California loyalty oath. Bancroft F870.E3 K18.

Papers pertaining to California loyalty oaths, 1954. Bancroft BANC MSS C-Z 92.

University of California, Berkeley Accounting Office loyalty oath records, 1949–1964. UC Archives CU-3.11.

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library has interviews on just about every topic imaginable. You can find the interviews mentioned here and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. We preserve voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public.