Tag: American history

Primary Sources: 1980s Culture and Society

The Library now has access to the online archive 1980s Culture and Society, which brings together resources from archival collections in the US, UK, Australia, and Canada.

The Library now has access to the online archive 1980s Culture and Society, which brings together resources from archival collections in the US, UK, Australia, and Canada.

“From the rise of Conservatism, the threat of nuclear war, and the AIDS crisis, to rampant consumerism, economic crises, and technological advancements, the 1980s was a turbulent and complex decade in which some individuals reaped significant benefits whilst others experienced severe poverty and hardship. Drawing on material from the late 1970s through to the early 1990s, this resource focuses on the voices of under-represented groups, grassroots organizations, and countercultural movements, addressing themes such as sexuality and identity, Black resistance movements, Indigenous land rights, subcultures, and health and social issues.

“These themes are represented within a broad range of sources which feature a variety of perspectives. For example, campaign materials, newspapers and newsletters from grassroots organizations and local communities provide a keen insight into social and political activism during the 1980s, whilst government papers and speeches from the Reagan and Thatcher administrations demonstrate the rise in political conservatism that dominated the decade. Collections of zines highlight the rich creativity and productivity of 80s subcultures, whilst mainstream and consumer culture is epitomised in fashion catalogues, photojournalism and gaming ephemera.” (Source)

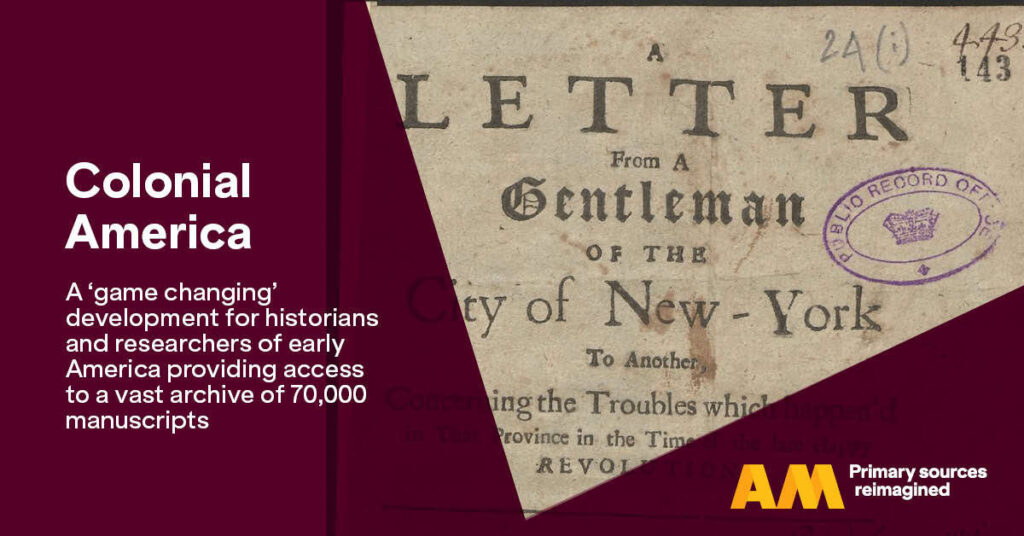

Primary Sources: Colonial America

The Library now has access to all five modules of Colonial America, a digital archive produced by AM (formerly Adam Matthew Digital). This resource provides an extensive collection of primary source documents related to the history of Colonial America, spanning from the 16th to the 18th century. The resource offers a comprehensive collection of materials that includes correspondences, diaries, maps, pamphlets, and other types of documents. These sources provide valuable insights into the social, political, and economic aspects of life during the colonial period in North America.

Primary source: Public Housing, Racial Policies, and Civil Rights

Public Housing, Racial Policies, and Civil Rights: The Intergroup Relations Branch of the Federal Public Housing Administration, 1936-1963 includes directives and memoranda related to the Public Housing Administration’s policies and procedures. Among the documents are civil rights correspondence, statements and policy about race, labor-based state activity records, local housing authorities’ policies on hiring minorities, court cases involving housing decisions, racially-restrictive covenants, and news clippings. The intra-agency correspondence consists of reports on sub-Cabinet groups on civil rights, racial policy, employment, and Commissioner’s staff meetings.

Public Housing, Racial Policies, and Civil Rights: The Intergroup Relations Branch of the Federal Public Housing Administration, 1936-1963 includes directives and memoranda related to the Public Housing Administration’s policies and procedures. Among the documents are civil rights correspondence, statements and policy about race, labor-based state activity records, local housing authorities’ policies on hiring minorities, court cases involving housing decisions, racially-restrictive covenants, and news clippings. The intra-agency correspondence consists of reports on sub-Cabinet groups on civil rights, racial policy, employment, and Commissioner’s staff meetings.Primary source: Environmental History: Conservation and Public Policy in America, 1870-1980

The Library has gained access to the online archive “Environmental History: Conservation and Public Policy in America, 1870-1980” thanks to the Institute for Governmental Studies Library’s contribution of nearly 2,000 items to this collection.

The Library has gained access to the online archive “Environmental History: Conservation and Public Policy in America, 1870-1980” thanks to the Institute for Governmental Studies Library’s contribution of nearly 2,000 items to this collection.

A detailed description from the vendor’s website:

Starting in the late nineteenth century, in direct response to the Industrial Revolution, forces in social and political spheres struggled to balance the good of the public and the planet against the economic exploitation of resources. Environmental History: Conservation and Public Policy in America, 1870–1980 chronicles various responses in the United States to this struggle through key primary sources from individual activists, advocacy organizations, and government agencies.

Collections Included

- Papers preserved at Yale University of George Bird Grinnell, a founding member of the Boone and Crockett Club, one of the earliest American wildlands preservation organizations; a founder of the first Audubon Society and New York Zoological Society; and editor for 35 years of the outdoorsman magazine Forest and Stream, which played a key role as an early sponsor of the national park movement and Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918.

- Records housed at the Denver Public Library of the American Bison Society, an organization that sought to save the American bison from extinction and succeeded as the first American wildlife reintroduction program.

- Also housed at the Denver Public Library, the papers of key women conservationists, such as Rosalie Edge and Velma “Wild Horse Annie” Johnston. Edge formed the Emergency Conservation Committee to establish Hawk Mountain Sanctuary (the first preserve for birds of prey), clashed with the Audubon Society over its policy of protecting songbirds at the expense of predatory species, and was a leading advocate for establishing the Olympic and Kings Canyon national parks. Johnston worked to end the capture and killing of wild mustang horses and free-roaming donkeys and lobbied to protect all wild equine species.

- Documents held at various institutions of the “father of forestry” Joseph Trimble Rothrock, who served as the first president and founder of the Pennsylvania Forestry Association and Pennsylvania’s first forestry commissioner. Rothrock’s work acquiring land for state parks and forests illustrates the role of key actors at state and regional levels.

- Project histories and reports of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation from the National Archives and Records Administration, chronicling the bureau’s work on projects including Belle Fourche, South Dakota; Grand Valley, Colorado; Klamath, Oregon; Lower Yellowstone, Montana; Shoshoni, Wyoming; and more.

- Select gray literature on conservation and environmental policy from the Institute of Governmental Studies Library at the University of California at Berkeley. This vast array of documents issued by state, regional, and municipal agencies; advocacy organizations; study groups; and commissions from the 1920s into the 1970s cover wildlife management, land use and preservation, public health, air and water quality, energy development, and sanitation.

Primary Sources: Environmental History: Conservation and Public Policy in America, 1870-1980

Environmental History: Conservation and Public Policy in America, 1870-1980 is a digital archive from Gale that provides access to sources documenting the emergence of conservation movements and the rise of environmental public policy in North America from the late 19th to the late 20th century.

The archive offers an incisive view into the efforts of individuals, organizations, and government agencies that shaped modern conservation policy and legislation. It includes:

- Papers of early environmentalists like George Bird Grinnell, a founding member of the Boone and Crockett Club and the first Audubon Society, and Joseph Trimble Rothrock, known as the “father of forestry.”

- Records of the American Bison Society, which helped save the American bison from extinction, and papers of women conservationists like Rosalie Edge and Velma “Wild Horse Annie” Johnston.

- Documents from the U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, and various state and municipal agencies focused on conservation and land-use matters.

- Grey literature from advocacy organizations, study groups, and commissions covering wildlife management, land preservation, public health, energy development, and more.

This archive provides valuable context for understanding today’s environmental challenges by chronicling the historical struggle to balance economic exploitation and resource conservation. It offers insights into the grassroots movements, advocacy efforts, and policy decisions that laid the foundation for modern environmental protection.

The resource includes grey literature on conservation and environmental policy from UC Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies Library.

World War II-era Japanese American Incarceration: A Guide to the Oral History Center’s Work

Anthology created by the Oral History Center

Research by Sari Morikawa, Serena Ingalls, and Timothy Yue, undergraduate researchers

After the entrance of the United States into World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, which mandated the forced removal of Japanese Americans from their homes on the West Coast into incarceration camps inland for the duration of the war. This forced removal uprooted families, disrupted businesses, and dispersed communities — impacting generations of Japanese Americans. The Oral History Center, or the OHC, and other archival collections in The Bancroft Library, feature several projects on this chapter of American history, comprising hundreds of interviews, photographs, artifacts, graphic illustrations, and podcasts for use by scholars and the public.

Find these interviews and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Find all the oral history projects mentioned here, along with more in-depth descriptions, on our projects page.

There are six parts to this collection guide to Oral History Center and other Bancroft Library resources:

- Projects about Japanese American incarceration

- Related projects

- Individual interviews

- How to search our collection

- Selected articles that highlight and synthesize this work

- Acknowledgements

Part 1: Projects about Japanese American Incarceration

Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives

The Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project is the OHC’s newest project on this subject, consisting of interviews with child survivors and descendants of those who were incarcerated. The project documents the ways in which intergenerational trauma and healing occurred after the United States government’s incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. Conducted by Roger Eardley-Pryor, Shanna Farrell, and Amanda Tewes, these interviews examine and compare how private memory, creative expression, place, and public interpretation intersect at sites of incarceration. Initial interviews focus on the Manzanar and Topaz prison camps, and pose a comparison through the lens of place, popular culture, and collective memory. Exploring narratives of healing as a through line, these interviews investigate the impact of different types of healing, how this informs collective memory, and how these narratives change across generations. The first set of interviews, comprised of 100 hours of oral history interviews with 23 narrators, continues to grow with interviews featuring child survivors and descendants of the Heart Mountain and Tule Lake prison camps.

“‘Dad, were you put in the camps?’ They didn’t talk about it. It was something you didn’t bring up…. He was honest but then he said, ‘But that happened in the past. You don’t need to dwell.’”

—Peggy Takahashi, on intergenerational silence related to her family’s incarceration

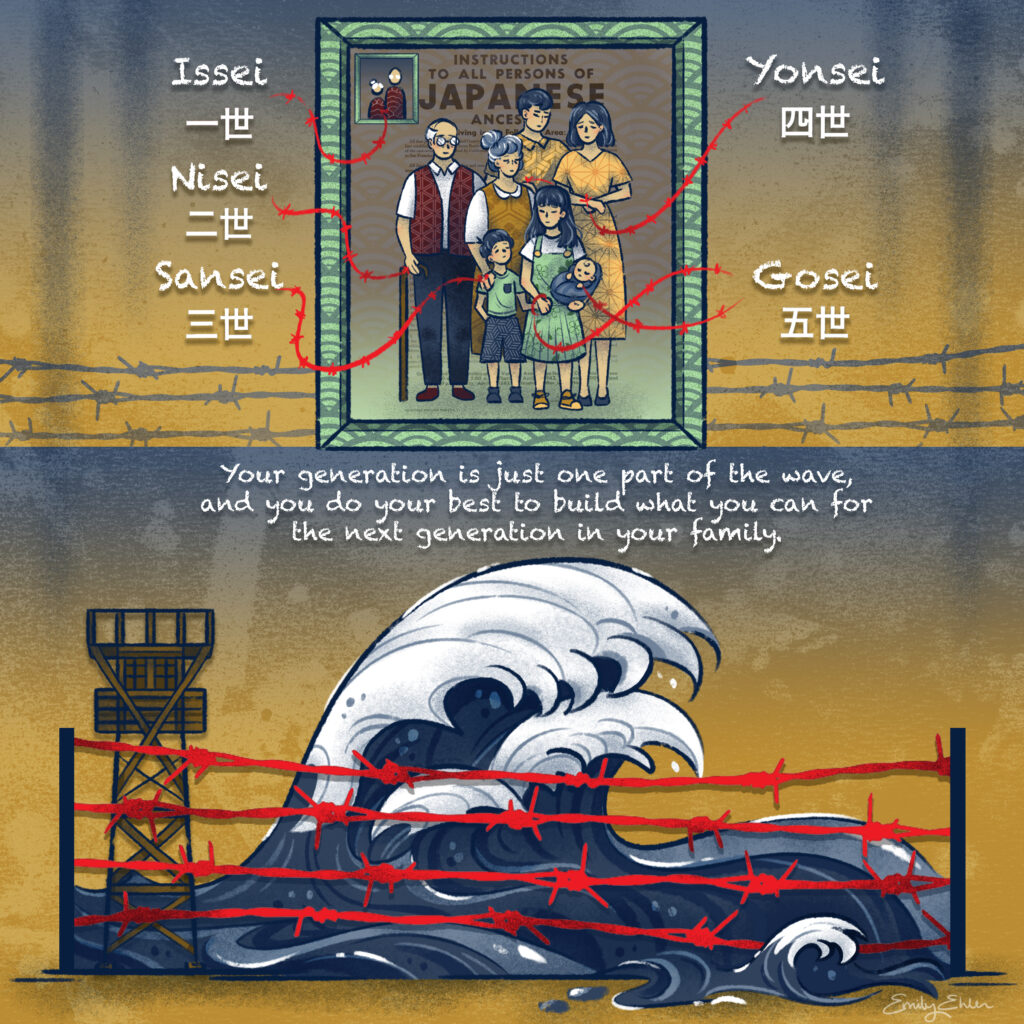

The project includes interpretive materials as well. Season eight of The Berkeley Remix, the OHC’s podcast based on oral history, explores themes from the project’s initial oral histories. “‘From Generation to Generation’: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration,” is a four-episode season featuring stories of activism, contested memory, identity and belonging, as well as artistic expression and memorialization of incarceration. In addition, ten graphic narrative illustrations created by artist Emily Ehlen vividly express the experiences of Japanese American incarceration during World War II and its effects on future generations. The interpretive materials, along with the oral histories, are available for use in classrooms.

Japanese American Confinement Sites

Interviews in the Japanese American Confinement Sites Oral History Project document the experiences of Japanese Americans who were incarcerated during World War II, including UC Berkeley students who attended college before or after the war. Themes running through these interviews include the experiences of forced relocation and incarceration; loss of property and livelihoods; identity; education; challenges faced after the end of the war; and emotional responses to their experiences. Many of the narrators went into fields such as public service, the military, advocacy, art, and education; some of them participated actively in the redress movement.

“Never again should there be such an event as a mass removal of an entire group of people without due process of law. … I try to pass that message on to as many people as I can.”

—Sam Mihara explains why he decided to become a speaker and share his stories

The voices of these narrators are brought to life in the slideshow: “The Uprooted: The Incarceration of Japanese Americans.” This slideshow was made to accompany the 2021–2022 exhibition in The Bancroft Library Gallery, “Uprooted: The Incarceration of Japanese Americans.” All photographs were drawn from the War Relocation Authority Photographs of Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement, 1942–1945, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, BANC PIC 1967.014–PIC. The oral histories are from the Japanese American Confinement Sites Oral History Project.

Japanese-American Relocation Reviewed

Japanese-American Relocation Reviewed is a multi-interview volume of oral histories from the Earl Warren in California project, dedicated to a discussion of Japanese American incarceration. In “Volume I: Decision and Exodus,” staff of the Justice Department, legal advisors to the US Army, and US and California State attorneys discuss the role of the US Department of Justice and the Western Defense Command in defining and administering policy towards enemy nationals, California Attorney General Earl Warren’s role in the forced removal of Japanese Americans to incarceration camps, the civil defense program, martial law, and the development of a constitutional argument for forced removal.

“We kept saying that we won’t do it and haven’t got the authority to do it. And there are enough precedents, you know with Lincoln suspending the writ of habeas corpus, that if the military wanted to do it, they could do it. But we frankly never thought they would. We thought they were too damn busy getting the troops to go fight a war some place else. That was our mistake.”

—James Rowe, assistant to United States Attorney General Francis Biddle

In “Volume II: The Internment,” members of the War Relocation Authority discuss the authority, selection, and administration of incarceration camp sites; resettlement out of the incarceration camps; origin and activities of the Pacific Coast Committee on American Principles and Fair Play. It also includes an appended interview with a wartime YWCA national board member on Idaho’s Minidoka camp in 1943; an address given by Robert B. Cozzens in 1945, “The Future of America’s Japanese;” and reproductions of Hisako Hibi’s paintings of Tanforan and Topaz.

The Office of Redress Administration Oral History Project

In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, a historic piece of legislation that sought, for the first time, to provide a measure of justice to Japanese Americans forty-six years after their incarceration during World War II. Over its decade-long operation (1988–1998), the Office of Redress Administration reached over 82,000 people with a redress payment and official apology letter from the President of the United States. Redress: An Oral History Project, by Emi Kuboyama, project creator and interviewer, with Todd Holmes, Oral History Center historian and interviewer, documents the complex history of Japanese American redress. The film, Redress, provides the first in-depth look at the historic program as told by both those who administered and participated in it. Additional educational materials supplement the film by providing historical overviews of the Japanese American experience and redress program, as well as a list of resources for further study and discussion. The project received the generous support of the Henri and Tomoye Takahashi Foundation and the National Park Service, US Department of Interior.

The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records and Japanese American Relocation Digital Archive

The Bancroft Library’s documentation of the Japanese American experience during World War II includes thousands of primary source materials drawn from an extensive collection of manuscripts, photographs, as well as audio and video. The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records, accessible through the Online Archive of California, consists of surplus copies of U.S. War Relocation Authority agency documents, including publications, staff papers, reports, correspondences, press releases, newspaper clippings, scrapbooks and a few photographs. Included is the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study, University of California, Berkeley, 1942-1946, containing diaries, letters and staff correspondence, reports and studies. These records include 250.5 linear feet (335 boxes, 84 cartons, 41 oversize volumes (folios), 7 oversize folders, 2 oversize boxes; 380 microfilm reels; 5,660 digital objects) (BANC MSS 67/14 c). The related Finding Aid to the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records 1930-1974 provides additional detail about the collection, including acquisition information, historic notes, scope, and contents.

In addition, Calisphere hosts the Japanese American Relocation Digital Archive (JARDA), which contains thousands of primary sources documenting Japanese American incarceration, including: personal diaries, letters, photographs, and drawings; US War Relocation Authority materials, including newsletters, final reports, photographs, and other documents relating to the day-to-day administration; and personal histories documenting the lives of the people who were incarcerated in the camps, as well as of the administrators who created and worked there. Curated by the University of California, JARDA makes accessible materials from libraries, museums, archives, and oral history programs across California.

Part 2: Related Projects

Rosie the Riveter World War II American Home Front Oral History Project

The Rosie the Riveter World War II American Home Front Oral History Project comprises more than 200 interviews with women and men about the home front experience in the Bay Area. Many of the interviews in these projects include either brief references to or longer discussions about the World War II-era incarceration of Japanese Americans, and cover a broad range of experiences from a multiplicity of perspectives. Some interviews feature individuals who were incarcerated, while other interviews feature Japanese Americans in Hawaii and elsewhere who were not, but who recalled being affected by fear and prejudice. Other interviews include people who were friends, classmates, neighbors, and coworkers, who recalled the forced removal, and the emotions they experienced. Some of these acquaintances were troubled or appalled, whereas others were relieved and thought it justified. Some took care of farms and property until their neighbors returned; others benefited financially. Some go into great detail about race relations in farming and other communities throughout California.

“We used to say, now, why did they make all the Japanese pilots look so ugly?”

—Gladys Okada, in reference to World War II American war films

Volumes about Earl Warren

Two projects, Earl Warren in California and Law Clerks of Earl Warren, center around Earl Warren, who was California’s attorney general (1939–43) and governor (1943–53), before becoming chief justice of the Supreme Court (1953–69), and include an interview with Warren himself. The California project focuses on the years 1925–53, and documents the executive branch, the legislature, criminal justice, and political campaigns; Warren’s life; and changes in California during this period. The California project includes numerous multi-interview volumes that address different issues, including two volumes on labor, exploring Warren from the perspective of union members and labor leaders. The Law Clerks project comprises interviews of more than 40 of Warren’s law clerks; these narrators discuss watershed cases, the evolution of constitutional law, and other issues related to the court. Among other subjects, issues that arose in the interviews in these projects included the ways in which the narrators responded to the executive order; economic, military, and other motivations for the order; the process of identifying individuals and where they lived; reparations; economic consequences; and reflections on Warren’s actions and opinions. Earl Warren himself, in his interview, Conversations with Earl Warren on California Government, briefly addresses the incarceration and aftermath, including enforcement and other issues related to the Alien Land law, preparation of maps documenting where Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans lived, rationale for incarceration, reparations, and return from the camps.

“‘We urge you to appoint immediately a trustee to hold in trust all the properties of the Japanese in this state… lest they be taken over by the wolves.’ They didn’t do anything. All the wolves came in and took over their property.”

—Richard Perrin Graves, executive of the League of California Cities and member of the Ninth Regional Civil Defense Board, on his telegram to the US attorney general

Related Papers

The Bancroft Library and greater UC Berkeley Library have extensive collections that address Japanese American incarceration during World War II and related matters. Here are a few. The complete files of the Fair Play Committee (Pacific Coast Committee on American Principles and Fair Play) are held in the library and include a comprehensive file of newspaper clippings from West Coast publications. The papers of Senator Hiram W. Johnson have information on land laws and Asian immigration. Senator James D. Phelan‘s records document anti-Japanese sentiment in the 1920s. The papers of Robert W. Kenny, who succeeded Earl Warren as attorney general in 1943, have information on law enforcement questions in the aftermath of forced relocation.

Part 3: Individual interviews

“We can’t deny that the black people who lived in the Western Addition moved into places that were vacated because [of] the Japanese Americans who were put into internment camps. Our relationship with Japanese Americans is somehow affected by that history.”

—Carl Anthony, architect and environmental justice activist

Dozens of individual interviews scattered throughout the Oral History Center archive, with people from different backgrounds and walks of life, also detail many facets of this chapter in history. Although they were interviewed about other matters, the narrators in their oral histories in some way addressed Japanese American incarceration — sometimes only in passing, at other times more in depth. Some of the more well-known narrators include the following. Photographers Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange discuss the artistic process, the ownership of their photographs, and the conditions in the camps. Willie Brown, speaker of the California Assembly and mayor of San Francisco, and Carl Anthony, architect and environmental justice activist, address race relations and how some black communities may have benefited from the forced relocation of Japanese Americans. Thomas Chinn, a historian and publisher of the Chinese Digest, discusses the evolution of race relations between Chinese and Japanese Americans in the United States, and noted that after Pearl Harbor, some people in Chinese communities wanted to distinguish themselves in order to avoid the same fate. Japanese American artist Ruth Asawa details her father being taken away by the FBI, her family’s subsequent incarceration, and the role incarceration played in her development as an artist.

“All this equipment my father had gathered — the books, everything that had to do with Japan — they just made a big bonfire and burned all of that. Everybody had panicked at that time. My sister cried and she said, ‘Oh, please don’t, don’t burn the books.’”

— Ruth Asawa, artist, on the fear her family experienced after her father was taken away

The best way to find individual OHC interviews that address any subject is to search by keyword from the search feature on our home page. Use as many keywords as you can think of (one at a time) that might relate to the topic. When you get to the results page, you will see a list of oral histories. Click on any one to get to detailed metadata about that oral history, plus access to the PDF of the oral history itself. As a first step, the abstract provides an overview of the major themes in the oral history. For a more comprehensive look, you can open the oral history directly from this page within digital collections; then use the search feature from within the oral history to find keywords. The oral history will also have a table of contents, and some also have an interview history and other front matter that will provide more information.

Part 4: How to search our collection:

Browse and access all of the oral history projects mentioned in this collection guide from the Oral History Center’s projects page. The projects page will provide a description of the project, and a list of all the oral histories on that project in the UC Library’s digital collections. To search the OHC’s archive by name, keyword, and other criteria, go to the OHC search feature on our home page. The OHC’s guides to various subjects in our collection can be accessed from the collections guide page. If you’re interested in making a documentary, podcast, or in undertaking other creative endeavors, you can access the audio/video and any related photos or ephemera through The Bancroft Library. You will need to open an account to order and access materials in the Reading Room. And here is more information about Rights and Permissions.

Explore collections related to Japanese American incarceration during World War II at all UC campuses by going to the UC Library Search. To explore all holdings from The Bancroft Library, go to the Advanced Search option from the Library Search page, and check “UC Berkeley Special Collections and Archives,” then search by keyword and other criteria.

Part 5: Selected articles that highlight and synthesize this work

The Oral History Center Presents the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project, by Shanna Farrell

The Oral History Center Presents The Berkeley Remix Season 8: “‘From Generation to Generation’: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration” by Amanda Tewes

Graphic Narrative Art by Emily Ehlen from OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, by Roger Eardley-Pryor

Q&A with Artist Emily Ehlen on Illustrating the OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, by Roger Eardley-Pryor

New podcast series explores the legacy of Japanese American incarceration: Read a Q&A with the Oral History Center’s Shanna Farrell about the Project, by UC Berkeley News reporter Anne Brice

‘I knew I had to draw it’: Illustrator brings to life testimonies of Japanese Americans incarcerated during WWII and their descendants in new Oral History Center project, by Dan Vaccaro, writer for UC Library Communications

Interconnections, by Roger Eardley-Pryor

Out of the Archives: Patrick Hayashi: From Mail Carrier to Associate President to Artist, by UC Berkeley undergraduate research apprentice Zachary Matsumoto

OHC URAP Student Zachary Matsumoto Reflects on Work with Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project, by UC Berkeley undergraduate research apprentice Zachary Matsumoto

‘Never again’: Library exhibit tells story of WWII Japanese American incarceration, sounds alarm on importance of remembering by Dan Vaccaro, writer for UC Library Communications

Oral history project highlights the little-known Japanese American redress program, by UC Berkeley News reporter Anne Brice

Redress: A film about the Office of Redress Administration by Edna Horiuchi in Discover Nikkei

Janet Daijogo: Japanese Incarceration and Finding Her Place through Aikido and Teaching, by UC Berkeley undergraduate and Oral History Center research assistant Deborah Qu

Bury the Phonograph: Oral Histories Preserve Records of Life in Hawaii During World War II, by UC Berkeley undergraduate and Oral History Center editorial assistant Shannon White

Part 6: Acknowledgements

National Park Service, Department of Interior

The following projects were funded, in part, by a grant from the US Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the US Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the US Government.

Japanese American Confinement Sites Oral History Project

Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project

Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records

Office of Redress Administration Oral History Project

Henri and Tomoye Takahashi Foundation

The Office of Redress Administration Oral History Project received generous support from the Henri and Tomoye Takahashi Foundation. The foundation also provided generous support for a second phase of interviews for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

About the Oral History Center

UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center, or the OHC, is one of the oldest oral history programs in the world. We produce carefully researched, recorded, and transcribed oral histories and interpretive materials for the widest possible use. Since 1953 we have been preserving voices of people from all walks of life, with varying perspectives, experiences, pursuits, and backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you would like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. The Oral History Center is a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. As such, we must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

Out of the Archives: Patrick Hayashi: From Mail Carrier to Associate President to Artist

by Zachary Matsumoto

“My mom told me that an old deaf man, Mr. Wakasa, was walking his adopted stray dog around the perimeter of the camp,” recalled Patrick Hayashi. “His dog caught in the barbed wire fence and Mr. Wakasa went to save him and release him. The sentry ordered him to back away from the fence, but because he was deaf, he couldn’t do it, and so the sentry shot and killed him.”

This is the story of James Wakasa’s murder, which Patrick Hayashi’s mother told him when he was growing up. Wakasa was one of over 100,000 Japanese Americans incarcerated by the US government during World War II. In the incarceration camp of Topaz in the desert of central Utah, an armed US soldier shot and killed Wakasa. His death sparked outrage among Topaz’s incarcerees. Although individuals in the Japanese American community contest some of the details of Wakasa’s death, it remains a key, painful moment in the incarceration experience that Japanese Americans have passed down to their children.

The story of Wakasa’s death certainly remained an important memory for Hayashi, a Sansei—or third generation Japanese American—who was born in Topaz while his parents were unjustly imprisoned there. Hayashi discussed his life and career with the Oral History Center at UC Berkeley. His interview was conducted as part of the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project, which explores trauma and healing across generations for Japanese Americans whose families were incarcerated during World War II.

As a young boy, after their release from the prison camp, Hayashi grew up with his parents in Hayward, California. His mother maintained ties to the Japanese American community, largely through church. However, when he was still young, Hayashi’s mother passed away of heart failure. This deeply saddened Hayashi’s father, who now carried the responsibility of raising a family as a single parent. Additionally, according to Hayashi, his father must have felt the guilt and shame from his incarceration experience in World War II. Nonetheless, Hayashi’s father exhibited resistance. He was a “no-no,” meaning he said “no” to two questions in an infamous loyalty questionnaire the US government forced upon the imprisoned Japanese Americans during WWII. The questions asked if one would be willing to serve in the US Army, and if one would swear loyalty to America and rescind loyalty to Japan. This sparked outrage among the Japanese American community, who were asked to serve a country that imprisoned them, and rescind a fealty to Japan that they didn’t have. Hayashi’s father’s “no, no” response was, as Hayashi believed, a “principled stand” against these unreasonable questions.

But his father never mentioned this resistance until Hayashi was an adult. Like many post war Japanese American families, Hayashi’s family did not often discuss their incarceration experiences.

Similar to his father, Hayashi also recalled feeling shame and guilt around incarceration and the war. In high school, he felt particularly ashamed of his identity when his class discussed WWII and the atomic bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki. At that time, Hayashi later recollected, “I was preferring not to be Japanese.” He also experienced a disconnect with the Japanese American community, largely due to his mother’s passing.Nevertheless, Hayashi shared many fond memories of his childhood, from reading Sherlock Holmes and science fiction books as an elementary schooler to becoming a star tennis athlete in high school.

If Hayashi felt shame due to his family incarceration, he channeled it into his work, starting in the 1960s. When reading his oral history, I noticed a theme of activism exhibited across his career in a near continuous fight for justice. After dropping out of college and working as a mail carrier, he found his calling in literature and became a UC Berkeley professor in the newfound Asian American Studies Department—one of the first such departments ever created. These developments for Hayashi came at the time of 1960s social movements in America. In one such movement, student protests in California universities led to the creation of an Ethnic Studies program at UC Berkeley.

Hayashi later became involved as a UC administrator, first working for Cal as the head of Student Conduct. After an investigation revealed that UC admissions were discriminating against Asian American applicants in the 1980s, Hayashi was appointed Associate Vice Chancellor of Admissions and Enrollment. In this position, and later as Associate President in the University of California, Hayashi worked on policy development and acted as an advocate for student applicants. He played a key role in fighting unfair admissions policies, such as the National Merit Scholarship Program (for discriminating against marginalized groups) and the Scholastic Aptitude Test or SAT (for not only explicitly favoring privileged students, but for also being, as Hayashi noted, a “bad test”).

One example of his advocacy came through at a meeting he attended soon after becoming Associate Vice Chancellor. In this meeting, Harold Doc Howe, Lyndon B. Johnson’s former Secretary of Education, communicated views with which Hayashi disagreed. Despite feeling nervous, Hayashi publicly challenged Howe in front of his colleagues. “My hands are actually trembling visibly in front of me and I said, ‘Howe begins with the assumption that a person’s writing ability reflects that person’s thinking ability. I don’t begin with that assumption. Instead I turn it into a question, and the question is to what extent does a person’s writing ability reflect that person’s ability to think?’ I said, ‘When you pose it as a question, the answer becomes obvious, it depends. If a person is new to the country or if the person is poor and has attended poor schools where the quality of education is low, then it’s incorrect and unfair to think that a person’s writing ability reflects that person’s thinking ability. Because oftentimes people just haven’t had the opportunity and the assistance to develop writing ability.’”

This, to me, demonstrates Hayashi’s sense of right and wrong – a fight against prejudiced assumptions in the admissions process.

Over time, too, Hayashi started to come to terms with the incarceration experience that his family hardly discussed and loomed over him like a cloud. One key moment for him occurred during his work as a UC professor. After reading James Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son, in which Baldwin discusses his experiences with racism and understanding the good his overbearing father did, Hayashi felt a better understanding both of his own father and his emotions. According to Hayashi, “[Baldwin] helped me understand my rage. And how if you’ve been suppressed constantly by racism, that goes somewhere and then it explodes. That was my pattern, and then it made me realize that it must have been my father’s experience as well. He was a proud man, he was smart, but it was clear, the injustice was clear to him and so it must have gone somewhere.”

To me, Hayashi’s understanding of Baldwin speaks to the emotional scars of incarceration that burdened many Japanese Americans. After experiencing racist injustice during World War II, anger would seem like a reasonable response. Perhaps the silence of many Japanese Americans after the war was the product of the internal, bubbling anger that people of color have felt throughout American history.

As Hayashi continued to come to terms with his family’s incarceration experience, James Wakasa’s story reemerged as an important moment. In the late 1980s, Hayashi visited an art exhibition from the incarceration camps, filling him with emotion. He recalled, “I choked up more and more and then the fourth painting I saw was Chiura Obata’s sumi-E sketch of James Wakasa falling over after he was shot, and I started to sob. It was terribly embarrassing, but everyone around me was mainly Nisei, they were crying too. That’s when I started revisiting the camps in a systematic way.”

Hayashi held true to his word. Later in life, he became more and more involved in the memorialization of Topaz, the camp of his family’s imprisonment. After retirement from Cal, Hayashi played a role in the creation and work of the Topaz Museum, located near the site of the former incarceration camp. He taught workshops at the museum for teachers in Utah, served as the keynote speaker at a 2016 Day of Remembrance event, and interviewed the Topaz class of ‘45—high schoolers who graduated in 1945 as Topaz incarcerees. Hayashi also took up painting as a major passion and a creative expression of his identity.

Hayashi’s life story is a reminder that one does not need to be defined by internalized pain of the past, but can instead come to terms with that pain and tell its story. The interviews and life stories told throughout the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project illuminate themes of memory, belonging, and healing. Hayashi’s life fully demonstrates each of these themes and serves as an inspiration for Japanese Americans pained by the past but who also want to make a difference.

To this day, he remains active in preserving the memory of incarceration. In 2016, Nancy Ukai, an activist who fought the auctioning of incarceration art, approached Hayashi with a request to create a painting for a Day of the Dead altar at a Japanese American cemetery. The request? To paint James Wakasa’s soul. His story, a source of intergenerational pain and important in Hayashi’s own life, now lay in the hands of Hayashi: a man who healed.

Patrick Hayashi’s oral history transcript is available on the OHC’s website.

Zachary Matsumoto is a sophomore at UC Berkeley currently studying History and participating as an Oral History Center URAP apprentice. He was drawn to the Oral History Center after attending a Bancroft Roundtable presentation about the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project. American history is a current academic interest of his, including the histories of communities relating to his background as a Chinese and Japanese American. In his free time, Zachary likes to go for runs, watch sports, and play taiko.

Luella Lilly: Cal’s first and only Director of Women’s Athletics

By William Cooke

In 1976, Luella “Lue” Lilly became the first and only athletic director of the newly created Women’s Intercollegiate Athletic Department at Cal. Over the course of her 17-year tenure, eight of the women’s sports programs won a combined 28 conference championships. In 1989, USA Today ranked Cal’s women’s athletics program number four overall in the nation. Today, several women’s programs are consistently among the best in the country and Cal female athletes, former and current, compete in the Olympic Games.

Now one of the premier destinations for elite female student athletes, Cal has come a long way from being one of the last universities in the country to create a women’s athletics department and offer scholarships to female athletes. That history starts with Lilly.

You don’t try to keep up with Joneses. You figure out where the Joneses are going to go and get there before they do. And that was my philosophy. —Luella Lilly

Lilly had a steep mountain to climb when she first arrived at Berkeley. Ongoing budget constraints, competition over the use of limited sports facilities, and tensions between departments meant that she could not fight every battle all at once. Her wisdom and guidance set up women’s athletics for a successful future. Lilly’s oral history, conducted by the UC Berkeley Oral History Center in 2010, describes when and how Lilly picked her battles.

Playing catch up

Cal hired Lilly in 1976, four years after Title IX was signed into law by President Richard Nixon. The law prohibited discrimination on the basis of sex at any institution receiving federal aid. Lilly recalls that the newly founded Women’s Intercollegiate Athletics Department had a lot of catching up to do in regard to providing women with equal athletics opportunities. According to Lilly:

Cal was the last major university in the United States to give an athletic scholarship to women. They gave scholarships after I arrived, and there were no scholarships prior to my arrival. And most of the schools—some of them gave them prior to ’72 and others—the majority of the schools, if they weren’t giving scholarships when Title IX went in, they gave some scholarships right away.

It was only in the fall of 1977 that Cal’s first batch of female recruits came to campus. Among them were Colleen Galloway, who held the record for career points in Cal Women’s Basketball history until 2019, and standout three-sport athlete Sheryl Johnson, who played in three Olympic games for USA field hockey.

In her first year at the helm, Lilly prioritized providing scholarships for a few reasons. In her oral history, Lilly explains that the Women’s Sports Foundation published a booklet annually that listed which schools provided scholarships in each sport. The department needed scholarships in order to compete for the best recruits, of course. But to be recognized nationally as a school that provided scholarships was just as important.

I also knew that when it [the Women’s Sports Foundation booklet] came out in February, that Cal would not be included or it wouldn’t say anything… Talking with [Vice Chancellor] Bob Kerley—[I] told him that we could jumpstart a full year if we could get some money to get the scholarships… and then when that little form came out I could check [it]. And so what I did was—they gave me—I think it’s $6,740 dollars, which was—tuition and fees were $670, I think they were, something like that. Anyway, it gave me ten tuition and fees at that point in time. So I gave them to each of the sports that could give scholarships, and had the coach divide it so that whatever way they wanted to—if they wanted to give somebody a full ride that was up to them, but if they wanted to split it among all—they could do anything they wanted to in their particular sport. But I just wanted to be able to mark the check that said we had them.

The money needed to provide scholarships and pay coaches—both of which are necessary in order to build a successful athletic program—would not and did not appear out of thin air. Lilly says in her oral history, “With fundraising we’ve—I think we’ve done most everything anybody has done in fundraising.” Even so, early fundraising results were disappointing.

One thing that really backfired and really, really surprised us was that we had Bruce [now Caitlin] Jenner and Steve Bartkowski play a demonstration tennis match—and it was five bucks to get in and all this sort of thing, and this was right after Jenner had won the Olympic decathlon, and we just assumed that everybody would really, really come. And nobody—we had so few people that we went up to the department and asked all the staff to please come down to put some more people in the stands. And we opened the gates and just let anybody that wanted to come, to come in to look for it, because it was so embarrassing how few came. And the thing I remember us saying too, that was probably with Chris Dawson. “You know, if this was a fundraiser for the men, the thing would be full.”

Support and strife

Ironically, men involved in Cal Athletics, including boosters, administrators, and journalists, were some of Lilly’s biggest supporters as well as her biggest adversaries. Lilly describes an environment of contentiousness over the scheduling of limited athletics facilities between the four athletics departments: Physical Education, Recreational Sports, Men’s Athletics, and Women’s Athletics. She believed that sometimes the tensions were understandable given Cal’s limited number of facilities; but, at other times, the competition between departments felt totally contrived.

A lack of cooperation meant that Lilly’s women’s programs had to deal with last-minute facilities scheduling changes, as well as explicit efforts to block cooperation between the men’s and women’s athletics departments. Lilly had to decide whether to resist those efforts or focus her energies elsewhere. Oftentimes she wavered between the two:

I think that cooperation is the main thing. I think you can really, really help each other… One of the things that I did do here was that I had all of my coaches and athletes give gold cards to all of their counterparts. I think the men’s gymnastics team should be able to watch the women’s gymnastics team free of charge, so I did that. And then [Vice Chancellor for student affairs] Bob Kerley talked to me and said that—here we go again—that [Men’s Athletic Director] Dave Maggard was upset with it, that we were trying to get tickets for the men’s events, and he went on and on about what I was trying to do, so I said to Bob, “All right. We won’t do it.” So then I came back the next year and I said, “I am not comfortable with this. I don’t like the fact that we can’t cooperate and have the men come to the women’s events. I don’t even care if he just thinks we’re trying to increase our attendance. The point is that you’re working together.” Because again, I came from that background of when the swimmers were on the same buses and that sort of thing, in high school. So it’s really hard for me to just think that everybody is so territorial. So Bob [Kerley] said, “If you feel that strongly about it, just go ahead and do it and we’ll just put up with the consequences.” So I had my coaches do it the next year.

Some instances of antagonism seemed inexplicable to Lilly who, as a volleyball and basketball coach at the University of Nevada prior to her tenure at Cal, learned the value of cooperation between the men’s and women’s coaches.

I said, “Well, let’s try to have a Christmas party and get to know some of the male staff. So all my coaches invited all the men coaches to come to a Christmas party, and the Alumni House gave it to us for free. This is where I say I had a lot of cooperation—they gave us the room; we didn’t have to pay for it. And nobody showed up except for the men’s football staff. And Roger Theder said nobody’s going to tell him what party he could and couldn’t attend. And another coach had told me that Maggard threatened that if anybody came to this party they’d be fired. So here’s all the women’s staff and eight football coaches. And we had a good time, you know. But that was just it; it was one of those situations again that just didn’t make any sense for me. The tennis coaches should know each other, and all this sort of thing.

Although Lilly found some adversaries in other sports-related departments, she found supporters of Cal Athletics elsewhere. In her oral history, Lilly says that “the strongest supporters that we’ve had and the people that have helped us the most along the way have been men.”

Doug Gray, a reporter at The Daily Californian, took an interest in Cal Women’s Athletics and began covering Lilly’s programs. Members of Cal’s athletics boosters, the Bear Boosters, slowly warmed up to the idea of supporting Lilly’s department. But many were reluctant to openly support the Department, which made for some odd interactions with male boosters. As Lilly recalled:

When I used to give my speeches it was really kind of funny, because I said I felt like a hooker or something, because the guys would never just come out and hand me money. They always—as I was saying goodbye they would either slip it in my pocket or they would shake my hand and leave the money in my hand. Or do all these little indirect things so that nobody knew that they were giving us any money!

And so when we were doing that, this one guy said, “If you ever let anyone, anyone at any time, ever know that I gave to the women’s program, I will never give you another cent.” He’d given us a whole twenty-five dollars; you’d think he’d given us millions. Anyway, but then later on after it became the big deal to give—and one of the awards that he got—and he said he was one of the first members of the Bear Boosters contributing and helping Women’s Athletics. Because at that point in time it was acceptable to do it. So he went from one extreme to the other. So we laughed when we saw that on his resume.

Muddling through

Fundraising picked up eventually, but for quite some time Lilly had to make do with limited resources. Lilly recalls diving into dumpsters and upcycling waste into equipment that the women’s programs needed for competitions. Among other things, Lilly made tennis poles to hold up the nets for doubles, poles for cross-country finish lines and a rolling cart for outdoor sports out of scrap wood she salvaged.

The women’s head coaches, who were already underpaid at less than $5,000 a year, lacked adequate office space and had access to just three phones between the twelve of them. So Lilly, with help from administration, created an office space:

And what we did then was—and then Bob Kerley made arrangements for me to go down to the surplus area and to get some desks, because we didn’t even have desks for the coaches. So what we did was we put two desks together with one of the bathroom partitions for a wall. And then we just went down that whole great big area that we had and made little cubbyholes for the coaches. These things weren’t even attached; they were just between two desks. And then we cut out a hole at one end of them and made a little flap so you could put a telephone on it. And then the telephone was passed back and forth from one coach to the other for the various sports, so that there was a little platform for them to be able to put the telephone, but we only had three telephones. There were twelve sports.

At various points throughout her oral history, Lilly points to instances in which she might have made a very different decision but chose not to. For example, in the early 1980s, recruiting became even more competitive. Some recruits began to ask for free cars in exchange for their commitment, a request that she suspected other schools fulfilled. Lilly says she refused to give in, and her women’s programs lost out on excellent recruits as a result.

Similarly, when administration disallowed some women’s coaches from working under multiple departments at the same time, Lilly considered challenging the decision but ultimately chose not to.

They weren’t going to let the women coaches—for basketball, and Joan Parker for tennis—be able to be in our department and Physical Education at the same time. And yet at the same time, the wrestling, water polo, and tennis coaches and—a lot of them were coaching in the men’s sports and teaching— but I would have made a major men’s/women’s issue right at the very, very beginning, and I knew I had to get things established better than making that particular fight. So I didn’t fight with that particular issue, but I did go to Bob Kerley and say, “Since everything is in such turmoil right now, could we have a one-year extension on that particular issue?” So Joan Parker was able to coach tennis the first year, and Barbara Iten was able to coach basketball the first year that I was there, but with the idea that they would not be able to coach the next year because I would accept whatever their previous ruling was, because like I said, I wasn’t going to make that a major issue. I really had to tiptoe lightly, when I made an issue out of something and when I didn’t, and what things I let slip and which ones I didn’t, and where I took a really, really strong stand. And I had to try to think about what was best for women’s sports and then what was best for Cal.

Separate success

Even while Lilly had to grapple with some of the pitfalls of having separate mens and women’s athletic departments, she expresses discontent at the trend in collegiate athletics towards combining the departments. Cal Women’s Athletics merged with the men’s athletics department in 1992. Lilly points out that several women’s programs experienced a sudden downturn after the merger, dropping from national title contention year after year to irrelevance for quite some time. With separate leadership, Lilly argues, female athletes and women’s coaches are more well-represented. A single athletic director can’t represent everyone well.

I think a lot—again it has to do with leadership, and feeling that—you conveyed a lot of this to the recruits, that this was—you were in charge and this was what was going to happen, and so forth. And they could come and see [that a] woman is director at this time. I think it’s much more difficult, again, if you’ve got twenty sports, to pay the same amount of attention as you could get when you’ve got two leaders as opposed to one trying to do a bigger job… When they’re combined, I feel that anyone who would be in charge of a combined program would have the same difficulties. In other words, you are expected, for men’s football and basketball, no matter what, to be there. And yet, at the same time, you’ve got to try to balance all these other sports. But if you had—let’s say both [the men’s and women’s basketball] teams make it to the Sweet Sixteen, and you’re the athletic director, you know where you’re going to be.

Lilly’s legacy was and is still visible in the form of elite Cal female student athletes and alumni. Natalie Coughlin, for example, swam for Cal in the early 2000s. She’s now a 12-time Olympic medalist, including three gold medals. Photo: UC Berkeley

With the merging of the men’s and women’s departments, Cal Athletics relieved Lilly of her duties. But 30 years later, Lilly’s legacy lives on in the form of elite women’s athletics programs. For progress to be made, Lilly hoped to predict the future and act quickly in order to stay one step ahead of other institutions. She managed the growth of coaching staff personnel and salaries with both budget constraints and trends in college athletics in mind, accelerating Cal Women’s Athletics’ rise to prominence.

There was a progression, but one of my favorite sayings which I think I made up myself is, “You don’t try to keep up with Joneses. You figure out where the Joneses are going to go and get there before they do.” And that was my philosophy. And so I always tried to figure out where sports were going, where were salaries going, where was the pressure going to be, and so forth, and then try to get all that into one big picture and then do what I could do within the money that we had.

More than 21 of the 45 oral histories in the Oral History Center’s Athletics at UC Berkeley project mention Lilly and her work.

Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, keyword, and several other criteria.

William Cooke recently graduated from UC Berkeley with a major in political science and a minor in history. In addition to working as a student editor for the Oral History Center, he was a reporter in the Sports department at UC Berkeley’s independent student newspaper, The Daily Californian.

Related Resources from The Bancroft Library

The Bancroft Library has hundreds of materials related to athletics in California and beyond. Here are just a few.

Lilly’s oral history is part of the Oral History Center’s project, Oral Histories on the Management of Intercollegiate Athletics at UC Berkeley: 1960-2014. This project comprises forty-five published interviews, conducted by John Cummins. Cummins was the Associate Chancellor and Chief of Staff who worked under UC Berkeley Chancellors Heyman, Tien, Berdahl, and Birgeneau from 1984 through 2008. Intercollegiate Athletics reported to Cummins from 2004 to 2006. Among the interviewees are longtime Chair of the Physical Education Department Roberta Park and former Assistant and Associate Athletic Director in the Women’s Athletic Department Joan Parker.

Articles based on this oral history project

William Cooke, “Title IX in Practice: How Title IX Affected Women’s Athletics at UC Berkeley and Beyond”

William Cooke, “Heavy hitters: the modern era of athletics management at UC Berkeley”

William Cooke: Luella Lilly: Cal’s first and only Director of Women’s Athletics

Other resources from The Bancroft Library

Cal women athletes hall of fame. Inauguration ceremony… May 24, 1978. Bancroft Library/University Archives. UC Archives ; 308m.p415.hf.1978

Cal sports 80’s. A program to improve the environment for Intercollegiate athletics at the University of California, Berkeley. Bancroft Library/University Archives. UC Archives ; 308m.p41.csp.1980

A celebration of excellence : 25 years of Cal women’s athletics. Bancroft Library/University Archives. UC Archives Folio ; 308m.p415.c.2001

About the Oral History Center

The UC Berkeley Oral History Center preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. You can find all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public.

Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Oral History Project Wins Autry Public History Prize

The UC Berkeley Oral History Center (OHC) is thrilled to announce that OHC historian Todd Holmes and project partner Emi Kuboyama from Stanford University have won the 2023 Autry Public History Prize for their digital project, Redress: An Oral History. The award is given by the Western History Association for the best project in public history. Released to the public in 2022, the project documents the history of Japanese American Redress through oral histories and a documentary film, which are featured with related historical resources on a dedicated educational website.

Holmes and Kuboyama began the project in 2018 with the initial goal of documenting the history of the Office of Redress Administration (ORA), the little-known agency charged with administering redress by the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. Emi Kuboyama, the principal creator of the project, had a direct link to the agency and its work. As a native of Hawaii, she was no stranger to the history of Japanese American incarceration or the impact that dark period still held in Japanese American communities. She also began her legal career with the agency in 1994, an experience that had a profound impact on her personally and professionally.

In 2017, Kuboyama attended the OHC’s Advanced Oral History Institute to explore how oral history could help document the historic redress program and the work of the ORA. There she met OHC historian Todd Holmes and the two agreed to partner on the project. With the support of a Japanese American Confinement Sites grant from the National Parks Service, they conducted over a dozen interviews with former ORA staff, as well as community leaders affiliated with the program. The recordings and transcripts of those interviews are now housed at the Densho Digital Repository. Upon the completion of the oral history interviews, Holmes and Kuboyama recognized the need to put the history of the ORA into conversation with the experience of the Japanese American community in its forty-six-year journey from internment to redress. With the generous support of the Henri and Tomoye Takahashi Foundation, they enlisted the help of filmmaker Jon Ayon. The collaboration resulted in the film, Redress, which offers the first in-depth look at the history of Japanese American redress as told by the community members who took part in the program, and the government professionals who administered it.

The last part of this digital project was to create a website that would not only serve as a home for the oral histories and film, but also an educational space for students and the public to learn more about the history of redress. Created by Todd Holmes and Heidi Holmes, the website features two historical pages that supplement the film and oral histories, as well as a resources page that points visitors to related historical material such as books, films, and oral history collections. Since the project’s release in fall 2022, the website has received over 43,000 visitors.

The prize was awarded to Holmes and Kuboyama in October 2023 at the annual Western History Association Conference. In the awards program, the Autry Committee praised the Redress project as “an excellent model of professional public history practice that documents a moment in Western American History that has particular significance for today’s conversations about reparations within other marginalized groups.” The committee also applauded how the project “showcases the power of the medium of oral history.”

The Oral History Center congratulates Todd Holmes, Emi Kuboyama, and their partners on an outstanding project and contribution. For more on the history of Japanese American Redress, visit the project website. And to learn more about the Japanese American experience and the legacy of WWII, see the new oral histories of the OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives project, which are featured in the newest season of The Berkeley Remix podcast.

Resources

Redress: An Oral History website

Oral History Center’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project

The Berkeley Remix podcast: Season 8: “‘From Generation to Generation’: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration”

The Oral History Center Presents the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project

The Oral History Center is proud to announce the launch of the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project, featuring 100 hours of oral history interviews with 23 Japanese American narrators who are survivors and descendants of two World War II-era sites of incarceration: Manzanar in California and Topaz in Utah. The majority of these oral histories are live on the Oral History Center website, where you can learn more about the project and the interviews themselves.

Just a couple of months after the United States entered World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. This order authorized the government to forcibly remove more than 120,000 Japanese American civilians—even American-born citizens—from their homes on the West Coast, and put them into incarceration camps shrouded in barbed wire and patrolled by armed guards for the duration of the war. This imprisonment uprooted families, disrupted businesses, and dispersed communities—impacting generations of Japanese Americans.

Even as the intergenerational impacts of World War II-era incarceration still touch many Japanese American descendants today, some Americans remain unaware of this history. It was in the spirit of illuminating the wounds of incarceration that OHC interviewers Roger Eardley-Pryor, Shanna Farrell, and Amanda Tewes embarked on this series of oral histories to record the stories of child survivors and descendants. Using healing as a throughline, these life history interviews explore identity, community, creative expression, and the stories family members passed down about how incarceration shaped their lives.

The project began in 2021 with funding from the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant. The interviews were conducted remotely via Zoom due to the global COVID-19 pandemic. The OHC team gathered a group of stakeholders with ties to the community to advise the project. Dr. Lisa Nakamura, a clinical psychologist who is herself a descendant of the Topaz incarceration camp, led Healing Circles for the project narrators after their interviews to process the experience without the interviewers present.

In addition to the oral histories, the OHC team produced a podcast as Season 8 of The Berkeley Remix to highlight the narrative themes that emerged from the interviews. They also commissioned artist Emily Ehlen, who created ten illustrations based upon stories and themes recorded in the interviews.

The podcast, “‘From Generation to Generation’: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration,” is a four-episode season featuring stories of activism, contested memory, identity and belonging, as well as artistic expression and memorialization of incarceration. It was produced by Rose Khor, Roger Eardley-Pryor, Shanna Farrell, and Amanda Tewes, and narrated by Devin Katayama. All four episodes are live on the OHC’s SoundCloud and in your podcast feeds.

Emily Ehlen’s artwork can be found on the OHC’s blog website and is available for download for educational purposes. Roger Eardley-Pryor sat down with Emily to learn more about her background, her work, and her process of creating these graphic illustrations.

Please explore the oral history transcripts and videos, listen to season 8 of The Berkeley Remix, and view Emily Ehlen’s artwork for more about the OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project.

A special thanks to the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant for funding this project.

The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government.

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you would like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. The Oral History Center is a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. As such, we must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.