Tag: sports history

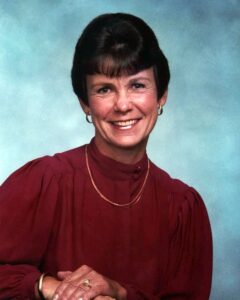

Luella Lilly: Cal’s first and only Director of Women’s Athletics

By William Cooke

In 1976, Luella “Lue” Lilly became the first and only athletic director of the newly created Women’s Intercollegiate Athletic Department at Cal. Over the course of her 17-year tenure, eight of the women’s sports programs won a combined 28 conference championships. In 1989, USA Today ranked Cal’s women’s athletics program number four overall in the nation. Today, several women’s programs are consistently among the best in the country and Cal female athletes, former and current, compete in the Olympic Games.

Now one of the premier destinations for elite female student athletes, Cal has come a long way from being one of the last universities in the country to create a women’s athletics department and offer scholarships to female athletes. That history starts with Lilly.

You don’t try to keep up with Joneses. You figure out where the Joneses are going to go and get there before they do. And that was my philosophy. —Luella Lilly

Lilly had a steep mountain to climb when she first arrived at Berkeley. Ongoing budget constraints, competition over the use of limited sports facilities, and tensions between departments meant that she could not fight every battle all at once. Her wisdom and guidance set up women’s athletics for a successful future. Lilly’s oral history, conducted by the UC Berkeley Oral History Center in 2010, describes when and how Lilly picked her battles.

Playing catch up

Cal hired Lilly in 1976, four years after Title IX was signed into law by President Richard Nixon. The law prohibited discrimination on the basis of sex at any institution receiving federal aid. Lilly recalls that the newly founded Women’s Intercollegiate Athletics Department had a lot of catching up to do in regard to providing women with equal athletics opportunities. According to Lilly:

Cal was the last major university in the United States to give an athletic scholarship to women. They gave scholarships after I arrived, and there were no scholarships prior to my arrival. And most of the schools—some of them gave them prior to ’72 and others—the majority of the schools, if they weren’t giving scholarships when Title IX went in, they gave some scholarships right away.

It was only in the fall of 1977 that Cal’s first batch of female recruits came to campus. Among them were Colleen Galloway, who held the record for career points in Cal Women’s Basketball history until 2019, and standout three-sport athlete Sheryl Johnson, who played in three Olympic games for USA field hockey.

In her first year at the helm, Lilly prioritized providing scholarships for a few reasons. In her oral history, Lilly explains that the Women’s Sports Foundation published a booklet annually that listed which schools provided scholarships in each sport. The department needed scholarships in order to compete for the best recruits, of course. But to be recognized nationally as a school that provided scholarships was just as important.

I also knew that when it [the Women’s Sports Foundation booklet] came out in February, that Cal would not be included or it wouldn’t say anything… Talking with [Vice Chancellor] Bob Kerley—[I] told him that we could jumpstart a full year if we could get some money to get the scholarships… and then when that little form came out I could check [it]. And so what I did was—they gave me—I think it’s $6,740 dollars, which was—tuition and fees were $670, I think they were, something like that. Anyway, it gave me ten tuition and fees at that point in time. So I gave them to each of the sports that could give scholarships, and had the coach divide it so that whatever way they wanted to—if they wanted to give somebody a full ride that was up to them, but if they wanted to split it among all—they could do anything they wanted to in their particular sport. But I just wanted to be able to mark the check that said we had them.

The money needed to provide scholarships and pay coaches—both of which are necessary in order to build a successful athletic program—would not and did not appear out of thin air. Lilly says in her oral history, “With fundraising we’ve—I think we’ve done most everything anybody has done in fundraising.” Even so, early fundraising results were disappointing.

One thing that really backfired and really, really surprised us was that we had Bruce [now Caitlin] Jenner and Steve Bartkowski play a demonstration tennis match—and it was five bucks to get in and all this sort of thing, and this was right after Jenner had won the Olympic decathlon, and we just assumed that everybody would really, really come. And nobody—we had so few people that we went up to the department and asked all the staff to please come down to put some more people in the stands. And we opened the gates and just let anybody that wanted to come, to come in to look for it, because it was so embarrassing how few came. And the thing I remember us saying too, that was probably with Chris Dawson. “You know, if this was a fundraiser for the men, the thing would be full.”

Support and strife

Ironically, men involved in Cal Athletics, including boosters, administrators, and journalists, were some of Lilly’s biggest supporters as well as her biggest adversaries. Lilly describes an environment of contentiousness over the scheduling of limited athletics facilities between the four athletics departments: Physical Education, Recreational Sports, Men’s Athletics, and Women’s Athletics. She believed that sometimes the tensions were understandable given Cal’s limited number of facilities; but, at other times, the competition between departments felt totally contrived.

A lack of cooperation meant that Lilly’s women’s programs had to deal with last-minute facilities scheduling changes, as well as explicit efforts to block cooperation between the men’s and women’s athletics departments. Lilly had to decide whether to resist those efforts or focus her energies elsewhere. Oftentimes she wavered between the two:

I think that cooperation is the main thing. I think you can really, really help each other… One of the things that I did do here was that I had all of my coaches and athletes give gold cards to all of their counterparts. I think the men’s gymnastics team should be able to watch the women’s gymnastics team free of charge, so I did that. And then [Vice Chancellor for student affairs] Bob Kerley talked to me and said that—here we go again—that [Men’s Athletic Director] Dave Maggard was upset with it, that we were trying to get tickets for the men’s events, and he went on and on about what I was trying to do, so I said to Bob, “All right. We won’t do it.” So then I came back the next year and I said, “I am not comfortable with this. I don’t like the fact that we can’t cooperate and have the men come to the women’s events. I don’t even care if he just thinks we’re trying to increase our attendance. The point is that you’re working together.” Because again, I came from that background of when the swimmers were on the same buses and that sort of thing, in high school. So it’s really hard for me to just think that everybody is so territorial. So Bob [Kerley] said, “If you feel that strongly about it, just go ahead and do it and we’ll just put up with the consequences.” So I had my coaches do it the next year.

Some instances of antagonism seemed inexplicable to Lilly who, as a volleyball and basketball coach at the University of Nevada prior to her tenure at Cal, learned the value of cooperation between the men’s and women’s coaches.

I said, “Well, let’s try to have a Christmas party and get to know some of the male staff. So all my coaches invited all the men coaches to come to a Christmas party, and the Alumni House gave it to us for free. This is where I say I had a lot of cooperation—they gave us the room; we didn’t have to pay for it. And nobody showed up except for the men’s football staff. And Roger Theder said nobody’s going to tell him what party he could and couldn’t attend. And another coach had told me that Maggard threatened that if anybody came to this party they’d be fired. So here’s all the women’s staff and eight football coaches. And we had a good time, you know. But that was just it; it was one of those situations again that just didn’t make any sense for me. The tennis coaches should know each other, and all this sort of thing.

Although Lilly found some adversaries in other sports-related departments, she found supporters of Cal Athletics elsewhere. In her oral history, Lilly says that “the strongest supporters that we’ve had and the people that have helped us the most along the way have been men.”

Doug Gray, a reporter at The Daily Californian, took an interest in Cal Women’s Athletics and began covering Lilly’s programs. Members of Cal’s athletics boosters, the Bear Boosters, slowly warmed up to the idea of supporting Lilly’s department. But many were reluctant to openly support the Department, which made for some odd interactions with male boosters. As Lilly recalled:

When I used to give my speeches it was really kind of funny, because I said I felt like a hooker or something, because the guys would never just come out and hand me money. They always—as I was saying goodbye they would either slip it in my pocket or they would shake my hand and leave the money in my hand. Or do all these little indirect things so that nobody knew that they were giving us any money!

And so when we were doing that, this one guy said, “If you ever let anyone, anyone at any time, ever know that I gave to the women’s program, I will never give you another cent.” He’d given us a whole twenty-five dollars; you’d think he’d given us millions. Anyway, but then later on after it became the big deal to give—and one of the awards that he got—and he said he was one of the first members of the Bear Boosters contributing and helping Women’s Athletics. Because at that point in time it was acceptable to do it. So he went from one extreme to the other. So we laughed when we saw that on his resume.

Muddling through

Fundraising picked up eventually, but for quite some time Lilly had to make do with limited resources. Lilly recalls diving into dumpsters and upcycling waste into equipment that the women’s programs needed for competitions. Among other things, Lilly made tennis poles to hold up the nets for doubles, poles for cross-country finish lines and a rolling cart for outdoor sports out of scrap wood she salvaged.

The women’s head coaches, who were already underpaid at less than $5,000 a year, lacked adequate office space and had access to just three phones between the twelve of them. So Lilly, with help from administration, created an office space:

And what we did then was—and then Bob Kerley made arrangements for me to go down to the surplus area and to get some desks, because we didn’t even have desks for the coaches. So what we did was we put two desks together with one of the bathroom partitions for a wall. And then we just went down that whole great big area that we had and made little cubbyholes for the coaches. These things weren’t even attached; they were just between two desks. And then we cut out a hole at one end of them and made a little flap so you could put a telephone on it. And then the telephone was passed back and forth from one coach to the other for the various sports, so that there was a little platform for them to be able to put the telephone, but we only had three telephones. There were twelve sports.

At various points throughout her oral history, Lilly points to instances in which she might have made a very different decision but chose not to. For example, in the early 1980s, recruiting became even more competitive. Some recruits began to ask for free cars in exchange for their commitment, a request that she suspected other schools fulfilled. Lilly says she refused to give in, and her women’s programs lost out on excellent recruits as a result.

Similarly, when administration disallowed some women’s coaches from working under multiple departments at the same time, Lilly considered challenging the decision but ultimately chose not to.

They weren’t going to let the women coaches—for basketball, and Joan Parker for tennis—be able to be in our department and Physical Education at the same time. And yet at the same time, the wrestling, water polo, and tennis coaches and—a lot of them were coaching in the men’s sports and teaching— but I would have made a major men’s/women’s issue right at the very, very beginning, and I knew I had to get things established better than making that particular fight. So I didn’t fight with that particular issue, but I did go to Bob Kerley and say, “Since everything is in such turmoil right now, could we have a one-year extension on that particular issue?” So Joan Parker was able to coach tennis the first year, and Barbara Iten was able to coach basketball the first year that I was there, but with the idea that they would not be able to coach the next year because I would accept whatever their previous ruling was, because like I said, I wasn’t going to make that a major issue. I really had to tiptoe lightly, when I made an issue out of something and when I didn’t, and what things I let slip and which ones I didn’t, and where I took a really, really strong stand. And I had to try to think about what was best for women’s sports and then what was best for Cal.

Separate success

Even while Lilly had to grapple with some of the pitfalls of having separate mens and women’s athletic departments, she expresses discontent at the trend in collegiate athletics towards combining the departments. Cal Women’s Athletics merged with the men’s athletics department in 1992. Lilly points out that several women’s programs experienced a sudden downturn after the merger, dropping from national title contention year after year to irrelevance for quite some time. With separate leadership, Lilly argues, female athletes and women’s coaches are more well-represented. A single athletic director can’t represent everyone well.

I think a lot—again it has to do with leadership, and feeling that—you conveyed a lot of this to the recruits, that this was—you were in charge and this was what was going to happen, and so forth. And they could come and see [that a] woman is director at this time. I think it’s much more difficult, again, if you’ve got twenty sports, to pay the same amount of attention as you could get when you’ve got two leaders as opposed to one trying to do a bigger job… When they’re combined, I feel that anyone who would be in charge of a combined program would have the same difficulties. In other words, you are expected, for men’s football and basketball, no matter what, to be there. And yet, at the same time, you’ve got to try to balance all these other sports. But if you had—let’s say both [the men’s and women’s basketball] teams make it to the Sweet Sixteen, and you’re the athletic director, you know where you’re going to be.

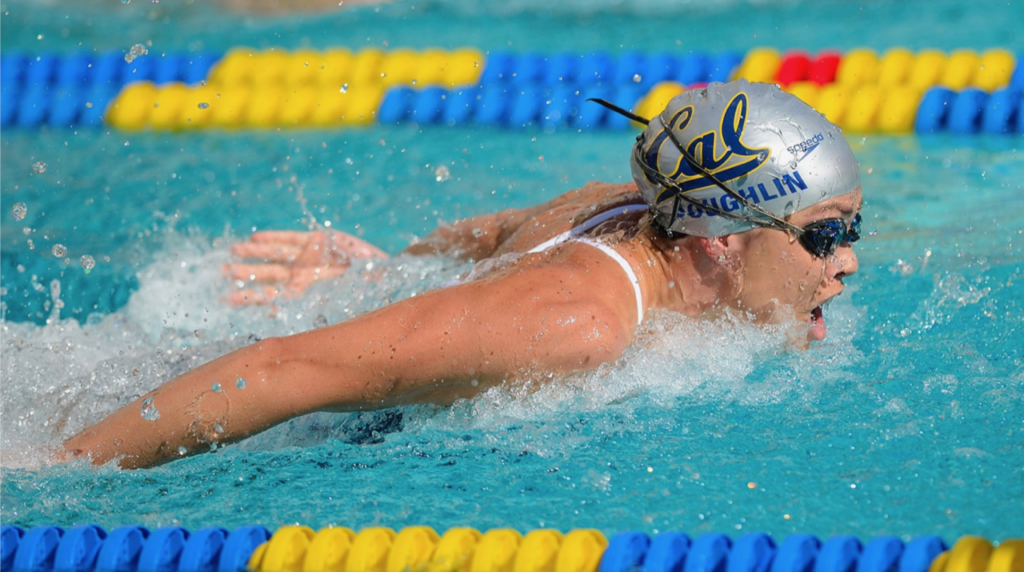

Lilly’s legacy was and is still visible in the form of elite Cal female student athletes and alumni. Natalie Coughlin, for example, swam for Cal in the early 2000s. She’s now a 12-time Olympic medalist, including three gold medals. Photo: UC Berkeley

With the merging of the men’s and women’s departments, Cal Athletics relieved Lilly of her duties. But 30 years later, Lilly’s legacy lives on in the form of elite women’s athletics programs. For progress to be made, Lilly hoped to predict the future and act quickly in order to stay one step ahead of other institutions. She managed the growth of coaching staff personnel and salaries with both budget constraints and trends in college athletics in mind, accelerating Cal Women’s Athletics’ rise to prominence.

There was a progression, but one of my favorite sayings which I think I made up myself is, “You don’t try to keep up with Joneses. You figure out where the Joneses are going to go and get there before they do.” And that was my philosophy. And so I always tried to figure out where sports were going, where were salaries going, where was the pressure going to be, and so forth, and then try to get all that into one big picture and then do what I could do within the money that we had.

More than 21 of the 45 oral histories in the Oral History Center’s Athletics at UC Berkeley project mention Lilly and her work.

Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, keyword, and several other criteria.

William Cooke recently graduated from UC Berkeley with a major in political science and a minor in history. In addition to working as a student editor for the Oral History Center, he was a reporter in the Sports department at UC Berkeley’s independent student newspaper, The Daily Californian.

Related Resources from The Bancroft Library

The Bancroft Library has hundreds of materials related to athletics in California and beyond. Here are just a few.

Lilly’s oral history is part of the Oral History Center’s project, Oral Histories on the Management of Intercollegiate Athletics at UC Berkeley: 1960-2014. This project comprises forty-five published interviews, conducted by John Cummins. Cummins was the Associate Chancellor and Chief of Staff who worked under UC Berkeley Chancellors Heyman, Tien, Berdahl, and Birgeneau from 1984 through 2008. Intercollegiate Athletics reported to Cummins from 2004 to 2006. Among the interviewees are longtime Chair of the Physical Education Department Roberta Park and former Assistant and Associate Athletic Director in the Women’s Athletic Department Joan Parker.

Articles based on this oral history project

William Cooke, “Title IX in Practice: How Title IX Affected Women’s Athletics at UC Berkeley and Beyond”

William Cooke, “Heavy hitters: the modern era of athletics management at UC Berkeley”

William Cooke: Luella Lilly: Cal’s first and only Director of Women’s Athletics

Other resources from The Bancroft Library

Cal women athletes hall of fame. Inauguration ceremony… May 24, 1978. Bancroft Library/University Archives. UC Archives ; 308m.p415.hf.1978

Cal sports 80’s. A program to improve the environment for Intercollegiate athletics at the University of California, Berkeley. Bancroft Library/University Archives. UC Archives ; 308m.p41.csp.1980

A celebration of excellence : 25 years of Cal women’s athletics. Bancroft Library/University Archives. UC Archives Folio ; 308m.p415.c.2001

About the Oral History Center

The UC Berkeley Oral History Center preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. You can find all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public.

Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Heavy hitters: the modern era of athletics management at UC Berkeley

By William Cooke

The last fifty years might be considered the modern era of intercollegiate athletics management in the United States. Ballooning TV contracts and Title IX have changed the college athletics landscape forever. The growing pains associated with those changes were felt by everyone involved with college sports, including those at UC Berkeley. The Oral History Center’s project, Oral Histories on the Management of Intercollegiate Athletics at UC Berkeley: 1960–2014, offers cross-sections of the Cal Athletics world during those formative years in the form of interviews with key internal and external actors.

For college sports fans, the history of the management of collegiate athletics at UC Berkeley is a familiar one. The unending conflict between maintaining a solid academic reputation and fostering winning programs, funding dilemmas, NCAA sanctions and the challenges surrounding gender inclusion in sports — common issues for every university athletic department — are all included in UC Berkeley’s storied athletics history.

These tensions and developments are reflected in the UC Berkeley Oral History Center’s project, Oral Histories on the Management of Intercollegiate Athletics at UC Berkeley: 1960–2014. Interviews between former UC Berkeley Associate Chancellor John Cummins — who served as interviewer — and a diverse cross sampling of individuals involved in the management of intercollegiate athletics, including athletic directors, chancellors, donors, and senior administrators, make up this collection of 45 publicly released interviews.

Organized by decade, here are a few snippets of the voices represented in this collection of oral histories. Themes in this collection include but are not limited to funding dilemmas, controversies surrounding academic standards for student-athletes, the evolving relationship between women’s and men’s sports, and the sometimes incompatible interests of athletic boosters and University officials.

The 1970s: The beginning of the modern era — Dave Maggard and Luella Lilly

The 40s and 50s were the golden years of Cal football and basketball. Led by legendary head coach Lynn “Pappy” Waldorf, Cal’s football program made three Rose Bowl appearances between 1948 and 1950. In 1959, head basketball coach Pete Newell led Cal to the program’s lone national championship to date.

A relatively disappointing decade followed for both programs. Then, in the early 1970s, catastrophe. When the NCAA found out that football and track athlete Isaac Curtis had failed to take the SAT as required, the intercollegiate governing body came down hard with sanctions.

Dave Maggard, who was appointed Athletic Director in 1972, argued against those in the administration and around Cal Athletics who wanted to fight the sanctions. These included the Golden Bear Athletic Association, an independent booster organization that had sued the NCAA in response to the sanctions. According to Maggard in his oral history:

When I became the athletic director I went to the administration and said, “This is a huge mistake. You cannot fight these people. We need to work to get on the inside, we need to get on committees, we need to be a part of the NCAA. I will tell you that they will rip this place apart, and this is something that you will never win. You will never win.”

The sanctions included probation and four years of bowl game ineligibility, a blow to the revenue stream of Cal’s most profitable program. Thanks to Maggard’s cooperation with the NCAA, though, the sanctions were eventually lifted.

At the same time, intercollegiate athletics at UC Berkeley took a huge step towards achieving gender equity in sports at the University. Following the passage of Title IX in 1972, the University hired its first director of Women’s Intercollegiate Athletics, Luella “Lue” Lilly.

Generating revenue for women’s athletics was a difficult undertaking. But Lilly made it a priority and found creative ways to raise funds and boost support for the newly established programs. Those efforts included the recruitment of a local politician and an Olympic gold medalist.

Then one time when we had— Dianne Feinstein and Ann Curtis were going to help us with the Mercedes raffle that we were giving out… We went over in front of city hall, and we just drove. We looked to see what was going to make the best picture, and there was a fountain behind it. We just drove the thing right up on the sidewalk.

If the 1970s was an era of immense change in athletics management at UC Berkeley, the next two decades would see the University settle its position on the relative importance of athletics and academics.

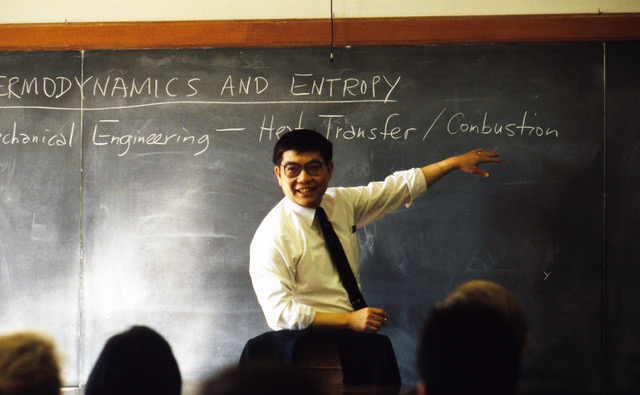

The 1980s and 1990s: The balance between school and sports — Chancellors Ira Michael Heyman, Chang-Lin Tien

When Chancellor Ira Michael Heyman took the reins from Albert Bowker in 1980, he inherited a sound athletics fundraising plan that Maggard had developed the decade prior. In many ways, Heyman supported the success of athletics at Cal, going so far as to allow “Blue Chip Admits” — 20 student athletes per year who would not normally be eligible to attend UC Berkeley.

But even while supporting athletic success at the calculated expense of lower academic standards, Heyman did not avoid criticism from UC Berkeley athletics boosters:

So they [The Grid Club] kept pushing me. “How important is athletics to you in relation to academics?” et cetera, et cetera. And I essentially said, “Academics, they’re really important. And intercollegiate athletics are of importance.” I just tried to make that distinction. And they said, “Well, on an index of one to ten where do athletics stand?” And I said, “Oh, about seven. Six and a half or seven.” That group never really warmed up to me.

In the early 1990s, Earl “Budd” Cheit, who served as the dean of the Haas School of Business, Executive Vice Chancellor and Interim Athletic Director over the course of his time at UC Berkeley, found himself right in the middle of that ongoing tension between winning and maintaining the University’s reputation for being first and foremost an elite academic institution.

Head football coach Bruce Snyder had led the Bears to a 10-2 season and a trip to the Citrus Bowl in 1991. Arizona State University doubled UC Berkeley’s annual salary offer of $250,000 to recruit Snyder.

Long-time supporter of UC Berkeley athletics Walter “Wally” Haas offered to match ASU’s offer along with the help of other boosters. But when Cheit relayed Haas’s message to Chancellor Chang-Lin Tien, the Chancellor shot the idea down and explained his reasoning.

Wally Haas called me during this time, and he said, “There are a number of people, myself included, who will come up with the money to match what he’s being offered. Will the Chancellor go for that?” And I called Chang-Lin and talked to him. And Chang-Lin said, “I can’t justify paying a coach that much more than the highest-paid professor on the campus.”

The 21st century: Changing priorities — Robert Berdahl, Robert Birgeneau

The 80s and 90s saw proponents of academic integrity and responsible spending win out over those who wanted Cal Athletics to accept the national shift toward a culture of commercialism in intercollegiate sports. The potential to rake in huge revenues from TV deals by investing in “revenue athletes” — student-athletes on the football and men’s basketball teams — drove the impetus to sacrifice academic standards for athletic success.

The hiring of Athletic Director Steven Gladstone in 2001 marked the beginning of a short, half-hearted effort to spend money in order to make money. Under Gladstone’s direction, coaching and administrative salaries were increased to attract and retain the very best in the intercollegiate athletics industry, all in the hope of making the two revenue sports — Cal football and men’s basketball — into elite college programs.

But with higher spending came concerns about the growing athletics budget deficit, which was compounded by the ever-growing cost of the newly built Haas Pavilion. In his interview with Cummins, Robert Berdahl, UC Berkeley’s Chancellor between 1997 and 2004, attributes some of the blame for deficit spending on the 1991 Smelser Report, which called for broad-based, highly competitive athletic programs in spite of budget constraints.

I think that the Smelser Report was a real disservice, because it created in the donor and booster community the notion we’re going to be as excellent in athletics as we are in academics, which I think is an unrealistic expectation for any high-quality university. I don’t think there’s any university of high quality that has that aspiration. Maybe Stanford, maybe Stanford’s the only one that does… But they don’t—they are competitive in football and basketball but rarely go to the Rose Bowl or to the NCAA championship.

Robert Birgeneau, who succeeded Berdahl as Chancellor, saw to it that priorities change under his leadership. To the dismay of some donors, Birgeneau replaced Gladstone with Athletic Director Sandy Barbour in 2004. During her tenure, Barbour facilitated the creation of the University Athletics Board (UAB), a committee that included faculty members and student athletes. Its purpose was to increase transparency in athletics spending by sharing this information with faculty for the very first time.

The Great Recession of 2008 made budget constraints even tighter. In 2010, Birgeneau made the difficult and controversial decision to cut four athletics programs — baseball, men’s and women’s gymnastics, and women’s lacrosse — and make rugby a club sport.

Because we had such loyal supporters of [Division] IA sports, I felt that they needed to know that the financial situation really was quite dire and that we needed them to step up, both themselves personally and to organize fundraising campaigns. As I said, that just simply did not happen… So, in this fateful September meeting, after the cold hard financial facts were presented to me, I agreed with the financial and IA people, that there really was not any choice. Specifically, we were never going to be able to achieve our goal of $5-million-a-year support from the campus without eliminating sports.

Supporters of those four sports eventually raised a combined $20 million in order to restore them to Division I status.

We worked out a compromise, basically asking each sport to raise enough funds to close their operating gaps for the next five to seven years… The baseball supporters raised nearly $10 million in six weeks. It is notable that philanthropy to baseball had been negligible for many, many years, and so there was a qualitative change. Indeed, this funding crisis brought the baseball community together, and in fact has resulted in us now having a stadium with lights at night. Thus, for baseball the situation actually is markedly improved.

These quotes represent just a small fraction of what this collection has to offer. Researchers will also find information on intra-departmental relationships, the personal experiences of former administrators in regards to particular decisions, and the retrospective opinions of both external and internal actors in the most crucial formative decades in the history of intercollegiate athletics management, both at UC Berkeley and institutions across the country.

Find these interviews and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, keyword, and several other criteria.

William Cooke is a fourth-year undergraduate student majoring in Political Science and minoring in History. In addition to working as a student editor for the Oral History Center, he is a reporter in the Sports department at UC Berkeley’s independent student newspaper, The Daily Californian.

Related Resources from The Bancroft Library

In addition to these oral histories, The Bancroft Library has related sources on Cal Athletics and intercollegiate athletics management more generally, including books on athletics facilities and fundraising, department records, and newspaper articles.

Read “Title IX in Practice: How Title IX Affected Women’s Athletics at UC Berkeley and Beyond,” also by William Cooke.

Related oral histories include Brutus Hamilton, Student athletics and the voluntary discipline : oral history transcript / and related material, 1966-1967 and Peter F. Newell, UC Berkeley athletics and a life in basketball.

66 years on the California gridiron, 1882-1948; the history of football at the University of California. Brodie, S. Dan. 1949. Bancroft BANC F870.A96 B7

A celebration of excellence : 25 years of Cal women’s athletics. Compiled by Kevin Lilley, Lisa Iancin, and Chris Downey. UC Archives Folio ; 308m.p415.c.2001.

Pamphlets on athletics in California. Bancroft Pamphlet Double Folio ; pff F870.A96 P16.

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page.

Title IX in Practice

How Title IX Affected Women’s Athletics at UC Berkeley and Beyond

By William Cooke

Title IX, a federal civil rights law passed in 1972 that amended the 1964 Civil Rights Act, prohibits discrimination based on sex at any educational institution that receives federal funding. While it pertains broadly to all forms of sex-based discrimination, the law arguably precipitated the most change in the arena of intercollegiate athletics. In any case, the passage of Title IX half of a century ago represents perhaps the single most significant event in the history of intercollegiate athletics in the United States, and was a major victory in the realm of civil rights for women.

The UC Berkeley Oral History Center houses a rich collection of interviews between oral historians and a diverse set of individuals that touch upon Title IX. In these interviews, influential figures across many different fields including intercollegiate sports, academia, and politics provide their insight into Title IX and its implementation over the course of the past fifty years.

“Title IX was fantastic for women in politics. It has created a generation of risk takers, in the best of ways.” —Mary Hughes, political consultant

Here are just a handful of voices that mention the transformative 1972 law across a few of the Oral History Center’s many collections.

In her oral history, Mary Hughes, a long-time Democratic political consultant who once served as the executive director of the California Democratic Party, recognizes the underappreciated role of Title IX and gender inclusion in sports in preparing women for positions of leadership in politics.

I attribute a lot of their success to Title IX, and here’s why: Title IX was fantastic for women in politics, both those who have supported and strategized to get women into office, and the women who have run. There is a difference between the women who grew up playing sports from a very young age and the women who did not… Their ability to be competitive without an irrational fear of failure is one of the most freeing things I’ve ever seen. I love these young, competitive women, and I hope we hold on to this, because it has created a generation of risk takers, in the best of ways, in the best of ways.

As a result of Title IX’s passage at the start of the decade, Luella Lilly became the first director of Women’s Athletics at Cal in 1976. The promise of equal opportunity for women in collegiate sports did not — and still does not — mean that men’s and women’s sports were resourced equally. One of Lilly’s priorities as director was to establish scholarships for female athletes for the very first time.

And so what I did was—they gave me—I think it’s $6,740 dollars, which was— tuition and fees were $670, I think they were, something like that. Anyway, it gave me ten tuition and fees at that point in time. So I gave them to each of the sports that could give scholarships, and had the coach divide it so that whatever way they wanted to. If they wanted to give somebody a full ride that was up to them, but if they wanted to split it among all— they could do anything they wanted to in their particular sport. But I just wanted to be able to mark the check that said we had them.

Joan Parker, a former Cal women’s basketball, softball, volleyball and tennis coach as well as assistant and associate athletic director in the Women’s Athletic Department for 13 years, praises Lilly for championing women’s sports when it was underfunded and underappreciated in the decades following 1972.

Lue came in, it was just—I was totally impressed with how she made things happen with so little money. It was just ridiculous when you compared our budgets to others… But Title IX definitely— and I think a lot of people didn’t understand it. A lot of outside— like our boosters and things like that, weren’t as aware of it. I think it was more of an internal pressure that at some point you’re going to be held accountable, and so you’d better start something in motion.

But while revolutionary and long overdue, Title IX also had some adverse, unintended consequences that still trouble university athletic programs.

Roberta Park was a supervisor of Physical Education at UC Berkeley until she stepped down after the passage of Title IX. She later served as the chair of the Department of Physical Education between 1982 and 1992. Park was a tireless champion of physical education programs and, in her oral history, makes it known that Title IX indirectly brought about a whole slew of repercussions for recreational sports programs that once benefited the entire student body. For one thing, elite athletes were prioritized over women’s widespread inclusion in sports.

I believed, and still believe, that colleges and universities (and high schools as well) should provide extracurricular sports programs for all interested women and girls, not just for the small number of the best athletes. Unfortunately, what evolved was an emphasis on the latter and an approach that gives the athletic program for a small number of the women athletes precedence over everything else… “We want to focus only on the women’s “varsity” basketball team, etc.” Well, if you put all of your efforts into a small number of the best athletes and you forget about all the others, what have you done? And that’s exactly what has happened. That’s exactly what has happened.

Another repercussion of Title IX was the merging of Physical Education and Intercollegiate Athletics departments at major universities across the country. This meant that sports programs for women were subsumed into intercollegiate athletics programs, sometimes causing women to lose higher-level administrative positions to men. After the passage of Title IX, Park pushed for the creation of a separate department of intercollegiate sports for women at UC Berkeley, which she argued was crucial to protecting female representation in intercollegiate athletics administration.

The emerging intercollegiate athletic sports for women, which used to be under the direction of Women’s Athletic Association or Women’s Recreation Association (which were directed by females, usually physical educators) were now all being moved over into Intercollegiate Athletics. With very, very few exceptions (in fact, I can think of none except at women’s colleges) all the Directors positions were taken over by men: And one of the things that I said was, “Well, okay, men have been doing this longer, and fair enough, but if Title IX is supposed to be about equity, what about the equity of women as the directors?”… So they finally decided, and I— I guess pushed is the right word, to the extent that I thought was appropriate, in the direction of a separate unit for women.

Another issue that arose was in the way that equal opportunity was interpreted. Charles Young, the Chancellor of UCLA between 1968 and 1997, witnessed firsthand the evolution of Title IX’s implementation at a major Division I university from before its conception up until the late 1990s. Young found the policy of creating an equal number of men’s and women’s programs to be misguided and at times counterproductive.

The principles of Title IX are fantastic but I think the major problem was that they took equivalence or took opportunity. Instead of opportunity they looked at the balance. And so you create a women’s sport to get in balance and there isn’t anybody who wants to play it. So then you have to go out and recruit people to come play it. Well, the principle should have been, are you providing as much opportunity for the women students as you are for the men. But it’s driven up the number of sports. It’s caused good sports to be eliminated at UCLA.

Former UC Berkeley Athletic Director John Kasser, who served as AD between 1993 and 2000, claims in his interview that Title IX was unfair to the supporters of Cal men’s sports who had to subsidize women’s sports in order to continue funding men’s sports at a competitive rate.

But see, that’s the thing when we—I don’t blame—Title IX was absolutely right and has been wonderful for women’s athletics, but nobody ever came with a financial plan… And so they expected Men’s Athletics to raise the funds to support Women’s Athletics. And so when you talked about it—you couldn’t say, “Well, that’s not fair.” But it wasn’t fair. It wasn’t fair.

One could argue that Title IX’s pitfalls speak more to the systemic issues that have prevented female student athletes from enjoying the same access to resources as men and not, as some might argue, to the failure of the law itself to protect “fairness.” The historical disadvantages of women in college sports made growing pains inevitable and even healthy for a field that has been dominated by men from the outset.

Now, fifty years after Title IX’s inception, these interviews help us recognize not only that progress is never perfect or steady, but also just how much progress has been made in the way of gender equality in intercollegiate sports thanks to the ongoing struggle of marginalized groups for the recognition of their civil rights.

Find these and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, keyword, and several other criteria.

William Cooke is a fourth-year undergraduate student majoring in Political Science and minoring in History. In addition to working as a student editor for the Oral History Center, he is a reporter in the Sports department at UC Berkeley’s independent student newspaper, The Daily Californian.

About Title IX

Title IX of the Education Amendments to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed into law on June 23, 1972, by President Richard M. Nixon: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Related Resources from The Bancroft Library

The Bancroft Library has hundreds of materials related to athletics in California and beyond. Here are just a few.

See the Oral History Center’s (OHC) project, “Management of Intercollegiate Athletics at UC Berkeley: 1960–2014” which includes more than forty interviews with chancellors, athletic directors, faculty members, donors, and others involved in athletics at Berkeley. See also OHC’s “Education and University of California — Individual Interviews” featuring more than 150 faculty, senior administrators, and staff.

University of California, Berkeley. Department of Women’s Intercollegiate Athletics records, 1976-1993. UC Archives (NRLF) CU-566

A celebration of excellence : 25 years of Cal women’s athletics. UC Archives Folio 308m.p415.c.2001

Title IX self study, University of California, Berkeley, approximately 1977. UC Archives (NRLF) CU-509

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library has interviews on just about every topic imaginable. You can find the interviews mentioned here and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. We preserve voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public.

Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page.

Reflections from the OHC’s 2019 Graduate Student Fellow

Rudy Mondragón is the Oral History Center’s 2019 Graduate Student Fellow. He is a doctoral candidate at the University of California, Los Angeles working on a project that looks at the sport of boxing and the ways in which black and brown boxers politically and culturally express themselves via the famous ring entrance.

During the summer of 2019, he traveled to Rhode Island to interview professional boxer Kali Reis. When complete, his interview will be archived in our collection. Below are his reflections on this experience and how this will shape his graduate work.

“The Heart Beat of Our People”: My Experience With a World Champion

By: Rudy Mondragón

I spent three days in Rhode Island with a world champion. Kali “K.O. Mequinonoag” Reis is a fighter who is of Seaconke Wampanoag, Cherokee, and Nipmuc heritage as well as Cape Verdean. In her 11 years of boxing professionally, Kali has earned the International Boxing Association (IBA), Universal Boxing Federation (UBF), and World Boxing Council (WBC) middleweight world titles. In addition to these prestigious accolades, Kali made history, alongside her opponent Cecilia Brækhus, in becoming the first woman to be on a televised Home Box Office (HBO) fight card. This was the first time in their 45 years of televising fights that HBO showcased a women’s fight.

My research examines the ways in which boxers (un)intentionally utilize the ring entrance as a political space to communicate their politics, new identities and subjectivities, and at times the performance of dissent and resistance. I first heard about Kali leading up to her May 5, 2018 fight against Cecilia Brækhus. The way she centers her indigenous identity demonstrates the possibilities that exist in ring entrances for boxers to express themselves in a plethora of ways. My initial thought was that she is a curator of her ring entrances, creatively using fashion and style, music, and her entourage to communicate a powerful message of belonging, dignity, empowerment, and storytelling. When I saw her ring entrance that night, I knew it was necessary that her story be documented and incorporated into my dissertation research.

The timing of the UC Graduate Oral History Center Fellowship was perfect. Being a recipient of this award allowed me to do two things: First, it gave me the necessary resources to make the trip to Rhode Island and meet Kali in person and second, to document a 6-hour oral history that would be archived in The Bancroft Library for future use and public access.

the conditions of fighting under the hot lights. Photo by: Rudy Mondragón

I made the trip to Pawtucket, Rhode Island in mid-June. Immediately after landing in Boston, I hopped into my white Hyundai rental car and made the drive an hour south in the pouring rain to Kali’s home. There were warehouse buildings to my left and to my right was McCoy Stadium, the home of the Pawtucket Red Sox minor league baseball team. I finally arrived at her home, which was on the corner of a residential intersection. I knocked on the front door and out came Kali with a big smile and welcomed me inside.

I waited in the living room as she prepared for our first of three interviews. In her living room were her three championship belts as well as a signed purple 8-ounce Cleto Reyes glove that she intended to wear for her fight against Brækhus. Due to boxing politics and the demands of her opponents’ team, Kali was forced to wear 10-ounce gloves instead.

Kali called me over and walked me down to the basement of her home, which is a multifunctional space. In the room is a meditation tapestry wall hanging, a buddha, massage table for her reiki healing treatments, and tranquil waterfall sounds. The other part of the room is used by her partner, Stephanie, for her hairdressing and nail-tech work. The time had finally come for our first conversation.

As a critical sports studies researcher who uses ethnographic methods and conducts in-depth interviews and oral histories, centering the voices of professional fighters is a critical priority. The stories that fighters share are not simply stories. They are a way to remember the past and connect it with the future. Storytelling, according to Russell Bishop, is a useful and culturally appropriate way to represent multiple truths because the storyteller retains control of their narrative.

In the three days and six hours of interview time with Kali, we were able to peel back the layers of her elaborate ring entrance. She described the parallels of her ring entrance with her experiences in attending powwows and fancy dancing:

“It’s a grand entry. So, at the beginning of a pow wow, to open up ceremony of a pow wow, you’ll have your warriors, your veterans, and you have the tribal flags. And there’s usually no video taking. It’s very sacred, you’re opening up the circle, you’re allowing your elders and everybody to open up that circle for you. So, basically my (ring) entrance is the same way. It’s becoming a grand entry, because every time I fight at home, there’s more and more dancers. But it’s a grand entry into that battlefield, into that square circle.”

Kali’s breakdown here demonstrates the ways in which her lived experiences as an indigenous person directly inform and manifest in her ring entrance. Her ring entrance is very similar to a powwow’s grand entry, the only difference, as she states, is that the end of her entrance marks the beginning of her battle inside the ring.

Her ring attire, created by Angel Alejandro from Double A Boxing, consists of a process that includes Kali sharing her vision for her ring robe and trunks with Angel. That is followed up by conversations between the two so that visionary and designer are on the same page. The ring attire she wore in her fight against Brækhus for example, included the colors white and purple, which represent royalty. Purple is the color of wampum shells, used for jewelry and belts made for Sachems and Chiefs. On the back of her sleeveless robe are two feathers, which represent her two spiritedness. Since the feathers are placed upward, they signify war. Feathers down, she states, symbolizes peace.

Kali’s entourage is something that is created on a fight to fight basis. In addition to making sure that she has “strong women dancing” her to the ring, she also believes “that the creator will send the right people to dance in front of me.” This is exactly what she did for her fight against Brækhus. The week prior to her Cinco de Mayo showdown, Kali put out a call on her social media platforms, calling on all “CALIFORNIA NATIVES.” She specifically asked if there were drummers and dancers willing to walk her to the ring. On the night of the fight, she had three dancers walk her to the ring. Two were of Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara heritage and one was Mashpee Wampanoag.

And in terms of her music, Kali described the drums in her ring entrance as “the heartbeat of our people” and “the voices that sing those songs are the cries of mother earth.” If Kali has indigenous people walk her to the ring, she allows them to pick whatever drums and songs they want. She does this because she firmly believes it’s the right way to honor them for honoring her and the collective of indigenous peoples around the world.

The original vision for my dissertation was to breakdown chapters thematically, intersecting boxing with how boxers deploy fashion and style, music and soundscapes, and entourages in their ring entrances. In the six hours I spent with Kali, she deconstructed her ring entrance to the extent that the three themes of expressive culture I analyze in my research were strongly articulated. This presented a new possibility, which has inspired a shift in the vision for my dissertation to add an additional chapter on oral history as a method and case-study that will focus solely on Kali Reis.

I reflected on my trip to Rhode Island a couple of days later and remembered a moment that meant a great deal to me. As Kali and I drove back to her home after enjoying a delicious vegan meal at the Garden Grille, she asked me who I thought would win in the upcoming fight between Manny Pacquiao and Keith Thurman. Here I was, sitting in a car with a professional practitioner of the sweet science, asking me for my thoughts on an upcoming fight. She asked me a meaningful question that resulted in a rich conversation. It made me think of the first time I ever reached out to Kali via Instagram and subsequent conversations that followed. Since then, Kali and I have built rapport and collective trust that contributed to the in-depth stories that she shared with me.

I can never see Kali as solely a research subject. I see her as a multifaceted and complex person who is the narrator of her story. She’s also become a friend of mine. There is no distancing myself from Kali as I begin the process of analyzing her oral history. On the contrary, there is going to be ongoing communication as well as ever increasing pressure. This pressure that I feel is not bad at all. I see it as an ongoing reminder that I have an obligation and responsibility to represent Kali’s story in an honorable, humanized, and just way.

This approach, in my opinion, is the right way to honor Kali’s story.