Tag: primary sources

Primary Sources: 1980s Culture and Society

The Library now has access to the online archive 1980s Culture and Society, which brings together resources from archival collections in the US, UK, Australia, and Canada.

The Library now has access to the online archive 1980s Culture and Society, which brings together resources from archival collections in the US, UK, Australia, and Canada.

“From the rise of Conservatism, the threat of nuclear war, and the AIDS crisis, to rampant consumerism, economic crises, and technological advancements, the 1980s was a turbulent and complex decade in which some individuals reaped significant benefits whilst others experienced severe poverty and hardship. Drawing on material from the late 1970s through to the early 1990s, this resource focuses on the voices of under-represented groups, grassroots organizations, and countercultural movements, addressing themes such as sexuality and identity, Black resistance movements, Indigenous land rights, subcultures, and health and social issues.

“These themes are represented within a broad range of sources which feature a variety of perspectives. For example, campaign materials, newspapers and newsletters from grassroots organizations and local communities provide a keen insight into social and political activism during the 1980s, whilst government papers and speeches from the Reagan and Thatcher administrations demonstrate the rise in political conservatism that dominated the decade. Collections of zines highlight the rich creativity and productivity of 80s subcultures, whilst mainstream and consumer culture is epitomised in fashion catalogues, photojournalism and gaming ephemera.” (Source)

Primary Sources: Colonial America

The Library now has access to all five modules of Colonial America, a digital archive produced by AM (formerly Adam Matthew Digital). This resource provides an extensive collection of primary source documents related to the history of Colonial America, spanning from the 16th to the 18th century. The resource offers a comprehensive collection of materials that includes correspondences, diaries, maps, pamphlets, and other types of documents. These sources provide valuable insights into the social, political, and economic aspects of life during the colonial period in North America.

Primary Sources: Amnesty International Archives, 1961-1991

The Library has recently acquired access to The Amnesty International Archives, which “publishes the records of Amnesty International from the second half of the twentieth century. The material contains minutes, reports, correspondence, first-hand accounts, publicity materials and circulars relating to human rights violations of all kinds in all parts of the world. Amnesty International’s remit of campaigning for an end to human rights abuses means that this archival material inherently relates to the themes of oppression, cruelty and degradation.” (Source)

Some of the collections include documents from outside the organization.

Primary Source: Egypt and the Rise of Nationalism

The Library has acquired access to Egypt and the Rise of Nationalism, an online collection of British government documents “that capture and reflect an era spanning from the first appearance of a nationalist sensibility to its gradual entrenchment in public life through protests, journalistic agitprop, lobbying activities, sporadic violence, and then — almost as a denouement — through an ordered political process, in the context and perspective of Britain’s evolving policy regarding Egypt.” (source)

The resource includes more than 4000 primary source documents dating from the 1870s until approximately 1924.

Primary source: Public Housing, Racial Policies, and Civil Rights

Public Housing, Racial Policies, and Civil Rights: The Intergroup Relations Branch of the Federal Public Housing Administration, 1936-1963 includes directives and memoranda related to the Public Housing Administration’s policies and procedures. Among the documents are civil rights correspondence, statements and policy about race, labor-based state activity records, local housing authorities’ policies on hiring minorities, court cases involving housing decisions, racially-restrictive covenants, and news clippings. The intra-agency correspondence consists of reports on sub-Cabinet groups on civil rights, racial policy, employment, and Commissioner’s staff meetings.

Public Housing, Racial Policies, and Civil Rights: The Intergroup Relations Branch of the Federal Public Housing Administration, 1936-1963 includes directives and memoranda related to the Public Housing Administration’s policies and procedures. Among the documents are civil rights correspondence, statements and policy about race, labor-based state activity records, local housing authorities’ policies on hiring minorities, court cases involving housing decisions, racially-restrictive covenants, and news clippings. The intra-agency correspondence consists of reports on sub-Cabinet groups on civil rights, racial policy, employment, and Commissioner’s staff meetings.Primary source: Environmental History: Conservation and Public Policy in America, 1870-1980

The Library has gained access to the online archive “Environmental History: Conservation and Public Policy in America, 1870-1980” thanks to the Institute for Governmental Studies Library’s contribution of nearly 2,000 items to this collection.

The Library has gained access to the online archive “Environmental History: Conservation and Public Policy in America, 1870-1980” thanks to the Institute for Governmental Studies Library’s contribution of nearly 2,000 items to this collection.

A detailed description from the vendor’s website:

Starting in the late nineteenth century, in direct response to the Industrial Revolution, forces in social and political spheres struggled to balance the good of the public and the planet against the economic exploitation of resources. Environmental History: Conservation and Public Policy in America, 1870–1980 chronicles various responses in the United States to this struggle through key primary sources from individual activists, advocacy organizations, and government agencies.

Collections Included

- Papers preserved at Yale University of George Bird Grinnell, a founding member of the Boone and Crockett Club, one of the earliest American wildlands preservation organizations; a founder of the first Audubon Society and New York Zoological Society; and editor for 35 years of the outdoorsman magazine Forest and Stream, which played a key role as an early sponsor of the national park movement and Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918.

- Records housed at the Denver Public Library of the American Bison Society, an organization that sought to save the American bison from extinction and succeeded as the first American wildlife reintroduction program.

- Also housed at the Denver Public Library, the papers of key women conservationists, such as Rosalie Edge and Velma “Wild Horse Annie” Johnston. Edge formed the Emergency Conservation Committee to establish Hawk Mountain Sanctuary (the first preserve for birds of prey), clashed with the Audubon Society over its policy of protecting songbirds at the expense of predatory species, and was a leading advocate for establishing the Olympic and Kings Canyon national parks. Johnston worked to end the capture and killing of wild mustang horses and free-roaming donkeys and lobbied to protect all wild equine species.

- Documents held at various institutions of the “father of forestry” Joseph Trimble Rothrock, who served as the first president and founder of the Pennsylvania Forestry Association and Pennsylvania’s first forestry commissioner. Rothrock’s work acquiring land for state parks and forests illustrates the role of key actors at state and regional levels.

- Project histories and reports of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation from the National Archives and Records Administration, chronicling the bureau’s work on projects including Belle Fourche, South Dakota; Grand Valley, Colorado; Klamath, Oregon; Lower Yellowstone, Montana; Shoshoni, Wyoming; and more.

- Select gray literature on conservation and environmental policy from the Institute of Governmental Studies Library at the University of California at Berkeley. This vast array of documents issued by state, regional, and municipal agencies; advocacy organizations; study groups; and commissions from the 1920s into the 1970s cover wildlife management, land use and preservation, public health, air and water quality, energy development, and sanitation.

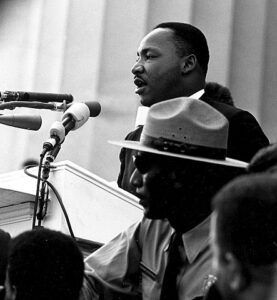

Primary Source: FBI Files on Martin Luther King, Jr.

Full text access to the FBI’s file on the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. is available on the GALE platform. “The 44,000-page case file … documents the bureau’s role in finding Ray and obtaining his conviction. The file also includes background information amassed by the FBI on Dr. King’s social activism.”

Black Freedom Struggle in the 20th Century: Federal Government Records, on the Proquest platform, includes the two FBI files on Martin Luther King, Jr. Part 1

“details the heavy surveillance and painful harassment that J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI directed against America’s foremost civil rights leader throughout the 1960s.” Part 2 consists of verbatim transcripts and detailed summaries of telephone conversations between King and one of his most trusted confidants, Stanley D. Levinson.

Primary Sources: Decolonization: Politics and Independence in Former Colonial and Commonwealth Territories

The Gale digital archive Decolonization: Politics and Independence in Former Colonial and Commonwealth Territories includes primary sources related to the complex process of decolonization across 60 former colonial territories and Commonwealth nations in the 20th century. The core content consists of over 250,000 pages of rare pamphlets, newsletters, correspondence, posters, and other ephemera produced by political parties, pressure groups, trade unions, and grassroots movements. This includes the Political Pamphlets collection from the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, African Trade Union pamphlets from Nuffield College at Oxford, and the Marjorie Nicholson Papers on international trade unionism.

The Gale digital archive Decolonization: Politics and Independence in Former Colonial and Commonwealth Territories includes primary sources related to the complex process of decolonization across 60 former colonial territories and Commonwealth nations in the 20th century. The core content consists of over 250,000 pages of rare pamphlets, newsletters, correspondence, posters, and other ephemera produced by political parties, pressure groups, trade unions, and grassroots movements. This includes the Political Pamphlets collection from the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, African Trade Union pamphlets from Nuffield College at Oxford, and the Marjorie Nicholson Papers on international trade unionism.

This archive is structured into thematic sections that address different facets of decolonization. These sections cover topics such as the rise of nationalist movements, key figures who led their nations to independence, and the residual impacts of colonial rule including economic dependencies and the development of new national identities. Additionally, it explores the involvement of international bodies like the United Nations in supporting decolonization efforts.

Primary Sources: Environmental History: Conservation and Public Policy in America, 1870-1980

Environmental History: Conservation and Public Policy in America, 1870-1980 is a digital archive from Gale that provides access to sources documenting the emergence of conservation movements and the rise of environmental public policy in North America from the late 19th to the late 20th century.

The archive offers an incisive view into the efforts of individuals, organizations, and government agencies that shaped modern conservation policy and legislation. It includes:

- Papers of early environmentalists like George Bird Grinnell, a founding member of the Boone and Crockett Club and the first Audubon Society, and Joseph Trimble Rothrock, known as the “father of forestry.”

- Records of the American Bison Society, which helped save the American bison from extinction, and papers of women conservationists like Rosalie Edge and Velma “Wild Horse Annie” Johnston.

- Documents from the U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, and various state and municipal agencies focused on conservation and land-use matters.

- Grey literature from advocacy organizations, study groups, and commissions covering wildlife management, land preservation, public health, energy development, and more.

This archive provides valuable context for understanding today’s environmental challenges by chronicling the historical struggle to balance economic exploitation and resource conservation. It offers insights into the grassroots movements, advocacy efforts, and policy decisions that laid the foundation for modern environmental protection.

The resource includes grey literature on conservation and environmental policy from UC Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies Library.

Primary Sources: Czechoslovakia Crisis, 1968: The State Department’s Crisis Files

Czechoslovakia Crisis, 1968: The State Department’s Crisis Files consists of documents collected and collated from a variety of State Department sources by the State Department’s Executive Secretariat, and represents an administrative history of the crisis. This collection includes almost a day-by-day record of the events, including the U.S. and the West’s response to the Soviet occupation.

The resources is organized in a series of subcollections:

- Czechoslovak Crisis Cable Chronology August 1968, Volume 1, Folder 2 “B”

- Czechoslovak Crisis Cable Chronology August 1968, Volume 1, Folder 3 “C”

- Czechoslovak Crisis Cable Chronology August 1968, Volume 1, Folder 4 “D”

- Czechoslovak Crisis Cable Chronology August 1968, Volume 1, Folder 5 “E”

- Czechoslovak Crisis Chronology August 1968, Folder 1 “A”

- Czechoslovak Crisis Miscellaneous Memos and MemCons Folder 6 “F”