Romance Language Collections

Universitas Linguarum

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Linguarum enim inscitia disciplinas universas aut exstinxit, aut depravavit…

For ignorance of languages either marred or abolished the world of learning….

—Erasmus, 1529, De pueris statim ac liberaliter instituendis. Opera I, 377

Berkeley’s celebration of languages in the Library could not come at a better moment. We are living in a time when many Americans are smugly self-satisfied about speaking English Only, when our government has waged an ugly war against immigrants, when linguistic and cultural otherness is too often construed as a threat, and when the world of learning is narrowing to a point where it may again be falling on unfortunate times.

The national trends are clear. A recent report from the Modern Language Association shows that 651 foreign language programs in American colleges and universities were lost between 2013 and 2016. And these are not all “less commonly taught” languages: according to the MLA report, during the 2013-16 period, net losses included 129 French programs, 118 Spanish programs, 86 German programs, and 56 Italian programs. Since 2009, overall foreign language enrollments have declined by 15.3 percent nationally. A recent Pew Research Center study showed that only 20% of American K-12 students study a foreign language (as compared to 92% in Europe).

Berkeley is not immune to decreases in language enrollments, but our programs remain unusually strong and have been staunchly supported by the Berkeley administration. In any given year, between 50 and 60 languages are taught on campus, and this remarkable breadth reflects the diversity of the State of California and the backgrounds and research interests of our students and faculty. California leads the nation in linguistic diversity: 42% of Californians speak a language other than English in their homes (as of 2016), and California has more than a hundred indigenous languages. Not surprisingly, this year’s incoming students speak more than 20 languages.

Globalization is ostensibly a strong impetus for language study — and it is in most parts of the world, where knowledge of English and other major languages is viewed as a fundamental necessity for participation in the global economy. However, in the U.S., it seems that globalization has had the opposite effect, leading many Americans to adopt a complacent attitude: why study other languages when so much of the world revolves around English?

Berkeley resists such complacency. We recognize that knowing other languages opens up fresh perspectives on the world, on our relationships with others, on our own language and culture, on the various disciplines we study, and on the problems we strive to solve. Indeed, so many of the challenges we face today are global in nature and can only be approached through the multiplicity of perspectives that come with international cooperation and collaboration. While English may allow for broad sharing of information, the reality is that we will never fully understand the nuances of other peoples’ perspectives if we don’t speak their language. Furthermore, because language, thought, and identity are so intimately intertwined, acquiring languages other than our mother tongue enriches our very being, allowing us to take on new identities, adopt new attitudes and beliefs, develop greater cognitive flexibility, and understand ourselves and our culture in a new light. Seeing the world through the lens of another language and culture also fosters empathy, which is essential to counter increasingly pervasive waves of ethno-nationalism.

Our university library reflects this awareness that languages nourish our imagination, enhance our creativity, and broaden and deepen our understanding of worlds past and present. More than one third of the 13 million volumes in UC Berkeley’s collection are in languages other than English. Remembering that the word university derives from the Latin universitas, signifying both universality and community, let us celebrate together the rich diversity of the Library’s holdings and of languages on the Berkeley campus.

Rick Kern,

Professor, Department of French

Director, Berkeley Language Center

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Portuguese (Brazil)

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

“A imaginação foi a companheira de toda a minha existência, viva, rápida, inquieta, alguma vez tímida e amiga de empacar, as mais delas capaz de engolir campanhas e campanhas, correndo.”

“Imagination has been the companion of my whole existence — lively, swift, restless, at times timid and balky, most often ready to devour plain upon plain in its course.” (trans. Helen Caldwell p. 41, Dom Casmurro)

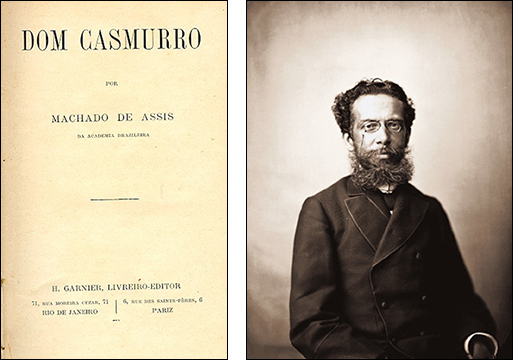

The novel Dom Casmurro is considered a masterpiece of literary realism and one of the most significant works of fiction in all of Latin American literature. The late Brazilian literary critic Afrânio Coutinho called it possibly one of the best works written in the Portuguese language, and it has been required reading in Brazilian schools for more than a century.[1] At UC Berkeley, generations of students in literature courses have been enjoying the rich complexity of this work of prose since the 1950s when the author began receiving recognition worldwide. Indelibly influenced by French social realists such as Honoré de Balzac, Gustave Flaubert and Émile Zola, Dom Casmurro is a sardonic social critique of Rio de Janeiro’s bourgeoisie. The satirical novel takes the reader on a terrifying journey into a mind haunted by jealousy via an unreliable first-person narrative told by Bento Santiago (Bentinho) who suspects his wife Capitú of adultery.

Dom Casmurro was written by multiracial and multilingual Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis (1864-1908) who was an essayist, literary critic, reporter, translator, government bureaucrat. He was most venerated for his short stories, plays, novellas, and novels which were all set in his milieu of Rio de Janeiro. The son of a freed slave who had become a housepainter and a Portuguese mother from the Azores, he grew up in an affluent household under a generous patroness where his parents were agregados (domestic servants).[2] A prodigy of sorts, he began writing at an early age, and quickly ascended the socio-cultural ladder in a country that did not abolish slavery until 1888 with the Lei Áurea (Golden Act).[3] At the center of a group of well-known poets and writers, Machado founded the Academia Brasileira de Letras (Brazilian Academy of Letters) in 1896, became its first president, and was perpetually reelected until his death in 1908.[4] “Even more remarkable than Machado’s absence from world literature,” wrote Susan Sontag, “is that he has been very little known and read in Latin America outside Brazil — as if it were still hard to digest the fact that the greatest author ever produced in Latin America wrote in the Portuguese, rather than the Spanish, language.”[5]

With a population of over 210 million, Brazil has eclipsed Portugal and its former colonies in Africa and Asia and now constitutes more than 80 percent of the world’s Portuguese speakers. Portuguese is the sixth most natively spoken language globally.[6] While European Portuguese (EP) is considered a less commonly taught language in American universities, this is not the case for Brazilian Portuguese (BP) where it has become increasingly popular. The Modern Language Association’s recently released study on languages taught in U.S. institutions, ranked Portuguese as the eleventh most taught language.[7] BP and EP are the same language but have been evolving independently, much like American and British English, since the 17th century. Today, the linguistic variations (phonetics, phonology, syntax, morphology, semantics, pragmatics) are so stark that a non-fluent observer might mistake the two for entirely different languages. In 1990, all Portuguese-language countries signed the Acordo Ortográfico da Língua Portuguesa — a treaty to standardize spelling rules across the Lusophone world — which went into effect in Brazil in 2009 and in Portugal in 2016.[8]

At Berkeley, Brazilian literature is offered for all periods and levels of study through the Department of Spanish and Portuguese’s Luso-Brazilian Program directed by Professor Candace Slater.[9] Her research centers on traditional narrative and cordel ballads, and she was awarded the Ordem de Rio Branco in 1996 — the highest honor the Brazilian government accords a foreigner — and in 2002, the Ordem de Merito Cultural. Other Brazilianists in the department include professors Natalia Brizuela and Nathaniel Wolfson. Graduate students with an interest in Brazil who are part of the Hispanic Language and Literatures (HLL), Romance Language and Literatures (RLL), and Latin American Studies programs delve into all aspects of the nation’s history, culture, and language.[10]

Contribution by Claude Potts

Librarian for Romance Language Collections, Doe Library

Sources consulted

- Coutinho Afrânio. Machado de Assis na literatura brasileira. Academia Brasileira de Letras, 1990.

- “More on Machado,” Brown University Library’s Brasiliana Collection. (accessed 7/19/19)

- Rodriguez, Junius P. Encyclopedia of Emancipation and Abolition in the Transatlantic World. Armonk, NY: Sharpe Reference, 2007.

- Preface to Dom Casmurro: A Novel by Machado de Assis. Translated by Helen Caldwell. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966, c1953.

- Sontag, Susan. “Afterlives: the Case of Machado de Assis,” New Yorker (April 29, 1990).

- CIA World Factbook (accessed 7/19/19)

- Modern Language Association of America. Enrollments in Languages Other Than English in United States Institutions of Higher Education, Summer 2016 and Fall 2016: Final Report (June 2019). (accessed 7/19/19)

- Vocabulário Ortográfico da língua portuguesa. 5a ed. São Paulo, SP : Global Editora ; Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil : Academia Brasileira de Letras, 2009; and Academia das Ciências de Lisboa. Vocabulário ortográfico atualizado da língua portuguesa. Lisboa : Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda, 2012.

- Portuguese (PORTUG) – Berkeley Academic Guide (accessed 7/26/19)

- Hispanic Languages & Literatures, Romance Languages and Literatures, Latin American Studies, UC Berkeley (accessed 7/25/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Dom Casmurro

Title in English: Dom Casmurro : novel

Author: Machado de Assis, Joaquim Maria, 1839-1908.

Imprint: Rio de Janeiro; Paris: Garnier, 1899.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Portuguese

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil

URL: http://acervo.bndigital.bn.br/sophia/index.asp?codigo_sophia=4883

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- O romance Dom Casmurro de Machado de Assis / Maximiano de Carvalho e Silva. Niterói : Editora da UFF, 2014. Includes the reproduction of the 1899 edition.

- Dom Casmurro. Ilustrações, Carlos Issa ; posfácio, Hélio Guimarães. São Paulo, SP : Carambaia, 2016.

- Dom Casmurro : A Novel. Translated from the Portuguese by John Gledson ; with a foreword by John Gledson and an afterword by João Adolfo Hansen. Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Dom Casmurro: A Novel by Machado de Assis. Translated by Helen Caldwell. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966, c1953.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Changes to MLA Bibliography & LION Databases

If you use Literature Online (LION) or the MLA International Bibliography, you may have noticed some changes recently.

The MLA International Bibliography and the MLA Directory of Periodicals will now be found solely on the EBSCO platform. Although the interface looks different, the functionality has not changed. The Bibliography indexes journal articles and other critical scholarship in literature, languages, linguistics, and folklore.

Continue reading “Changes to MLA Bibliography & LION Databases”

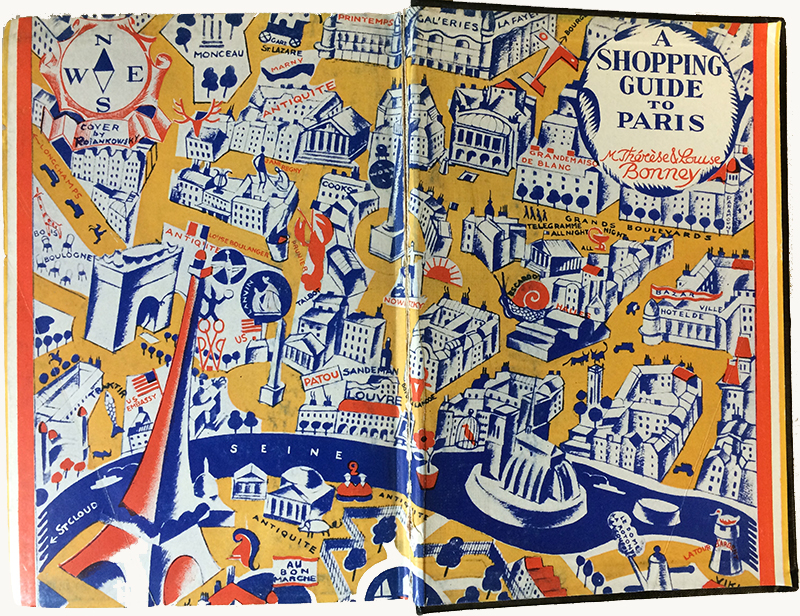

A Shopping Guide to Paris

Here’s a midsummer post to divert your attention to a fun travel guide written by an extraordinary Cal alumna (Class of 1916) and her sister Louise. In case you haven’t heard, the Thérèse Bonney papers and photographic archive have been processed and are available for use in The Bancroft Library:

- Finding Aid to the Thérèse Bonney Papers

- Finding Aid to the Thérèse Bonney Photograph Collection, circa 1850-circa 1955 (bulk 1930-1945) (2177 photos online)

Other books by Bonney can be found in the Main Stacks, or online through the HathiTrust Digital Library:

- Bonney, Thérèse. Europe’s Children, 1939 to 1943. New York: Rhode Publishing Company, 1944.

- Bonney, Thérèse, and Louise Bonney. French Cooking for American Kitchens. New York: Robert M. McBride & Co, 1929.

- Bonney, Thérèse, and Louise Bonney. A Guide to the Restaurants of Paris. New York: R.M. McBride, 1929.

Latin

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

The “golden age” of Latin comprises works produced between the first century BCE and the first century CE. The canon of Latin literature includes the works of such authors as Caesar, Cicero, Vergil, Horace, Livy, and Ovid, which frequently make up the core curriculum of any Classics department today.[1] Linguistically speaking, the Latin language became a predominantly literary and administrative language, learned by elite members of society who had an educational or professional need for it.[2] This does not mean that Latin was not spoken anymore, it just means that it ceased being anyone’s first language, and that, eventually, educated inhabitants of the broader Roman empire were bilingual, fluent in both Latin and in their own dialects (which became the Romance languages). The adoption of Latin as the unifying administrative language of the Roman empire — and later as the unifying administrative and liturgical language of the Roman Catholic Church — ensured Latin’s place as a global language through the 18th century.

The most influential ancient Roman author was Marcus Tullius Cicero. When students read Cicero today, they are likely to be assigned his famous speeches, such as the Catiline Orations or the Pro Caelio; one of his philosophical treatises, such as De re publica; or even his letters. What students may not know is that it was one of Cicero’s so-called juvenile works, written before he was 21 years old, that had the most outsized impact on the history of education in the West. Cicero wrote De inventione when he was studying rhetoric as a young man. The title topic “invention” (meaning “discovery”) refers to the first, and most important, task of the orator, which is to develop effective arguments that will persuade a judge. Because De inventione was written as a series of notes, it was easily adaptable to the classroom as a handbook for teaching rhetoric. De Inventione became such a foundational text in the medieval and Renaissance classroom that 322 complete manuscripts survive today.[3] As a result, Ciceronian rhetoric thoroughly permeated medieval and Renaissance intellectual culture and greatly influenced the literature, historiography and political theory of those periods, the fruits of which students continue to learn in humanities courses today.[4]

That Renaissance artists and architects looked to ancient sculptures, paintings, and architecture to inform their designs is well known. Renaissance Latin authors similarly looked to Classical authors as models for writing the “best Latin.” These humanists, as they are called, were reacting against what they saw as idiosyncratic Latin that evolved from the 11th to the 13th centuries to accommodate the highly technical and abstract concepts of theology and philosophy, and they desired a return to what they deemed the best models from antiquity: Cicero for prose and Vergil for poetry.[5] The Italian humanists Pietro Bembo and Jacopo Sadoleto of Italy, and the Belgian humanist Christophe de Longueil, went so far as to declare Cicero the only model for good Latin. The eclectic thinker and scholar Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466-1536) found this idea so ridiculous — because slavish imitation of a single model does not account for individual ability or changing times — that he penned a satirical dialogue titled Ciceronianus that mocked this idea of a single model. In his satire, the character Nosoponus is paralyzed by writer’s block, afraid to write a single word that is not found in Cicero; while Bulephorus endeavors to convince Nosoponus to seek out a greater array of authors as models and to internalize what he learns in order to develop his own style.[6] These arguments for some stylistic flexibility aside, the Renaissance marked the period during which the Latin language became well and truly fixed; by this time, the national vernacular languages had come into their own and Latin had become the domain of an elite educational curriculum.[7] The advantage to us of this fixing is that Latinists today are able to read, with relative ease, a wealth of texts that span more than a millennium.

The study of Latin has many applications and is an important tool for research and study in a variety of fields. Besides Classics, Berkeley students use Latin in courses within the department of Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology,[8] as well as PhD programs in Medieval Studies,[9] Romance Languages and Literatures,[10] and Renaissance and Early Modern Studies.[11]

Contribution by Jennifer Nelson

Reference Librarian, The Robbins Collection, UC Berkeley School of Law

Notes:

- Department of Classics, UC Berkeley

- Leonhardt 2013: 56-74.

- Two examples of manuscripts of De inventione are in the British Library (Arundel MS 348) and in the Kongelige Bibliotek in Denmark (GKS 1998 4°)

- Ward 2013: 167. (accessed 6/24/19)

- The notion that medieval Latin was fundamentally different from Classical Latin was a humanist construct. While, in some cases, there did exist identifiable regional flavors, evidence of certain non-“standard” constructions, or writing conventions developed for specific genres (frequently in the technocratic, bureaucratic, or legal realms), in general Latin did not change in any fundamental way in the period known as the Middle Ages.

- Nosoponus means “suffering from illness”; Bulephorus means “one who gives counsel.”

- Leonhardt 2013: 184-219.

- Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology (AHMA), UC Berkeley

- Program in Medieval Studies Program, UC Berkeley

- Romance Languages and Literatures, UC Berkeley

- Designated Emphasis in Renaissance and Early Modern Studies (REMS), UC Berkeley

Sources consulted:

- Erasmus, Desiderius. Dialogus cui titulus Ciceronianus, sive De optimo genere dicendi (Ciceronianus, or, A Dialogue on the Best Style of Speaking). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1976.

- Hubbell, H. M. Introduction to Cicero’s De inventione (On Invention), with an English translation by H. M. Hubbell. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1968, xi-xviii.

- Leonhardt, Jürgen (trans. Kenneth Kronenberg). Latin: Story of a World Language. Cambridge, Massachusetts : The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013.

- Ward, John O. “Ciceronian Rhetoric and Oratory from St. Augustine to Guarino da Verona.” In van Deusen, Nancy, Cicero Refused to Die: Ciceronian Influence Through the Centuries. Leiden: Brill, 2013, 163-196.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: De inventione ; De optimo genere oratorum ; Topica, with an English translation by H. M. Hubbell

Title in English: On Invention (and other works)

Author: Marcus Tullius Cicero

Imprint: Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1949.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Latin

Language Family: Indo-European, Italic

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Michigan)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/api/volumes/oclc/685652.html

Other online editions:

- Erasmus, Desiderius. Dialogus cui titulus Ciceronianus, sive De optimo genere dicendi (Ciceronianus, or, A Dialogue on the Best Style of Speaking). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1949.

Loeb Classical Library (UCB only), DOI: 10.4159/DLCL.marcus_tullius_cicero-de_inventione.1949

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

More French ebooks through OpenEdition

The Library has recently added 731 titles mostly in French but also Italian, Spanish, Portuguese and English to its ebook holdings through OpenEdition — an interdisciplinary open access initiative in France. Now, more than 4,700 academic ebooks in the humanities and social sciences are discoverable through the portal or through the Library’s catalogs permitting researchers to benefit from a range of DRM-free formats, some optimized specifically for e-readers, tablets, and smart phones (ePub, PDF, etc.). OpenEdition’s Freemium program makes it possible for UC Berkeley to participate in an acquisitions policy that supports openness and sustainable development of scholarly resources such as these.

Alain Trouvé

coordonné par Nicole Terrien et Yvan Leclerc

Michel Zink

David Dorais

Danielle Cohen-Levinas

Pierre-Louis Fort

Daniel Aznar, Guillaume Hanotin, Niels F. May

Luc Vancheri

Jean-Marc Guislin

Patrick Harismendy et Vincent Joly

Patrick Dramé

Sauveur Pierre Étienne

sous la direction de Luc Vincenti et al.

Abir Kréfa

Julien Baudry

Visit OpenEdition to read even more open access ebooks.

Catalan

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

I don’t want you to confine my thinking to facts and agreed formulas; I do want, like birds, the liberated wings to fly at any time, now to the right, now to the left, through the space full of infinite and invisible routes; I do not want extraneous nuisances, harmful limits that impose me a path beforehand. I want to be entirely master of myself and not a slave of alien forces, insofar as human, are miserable and failing. – Víctor Català (Caterina Albert), Insubmissió (1947)

(Trans. A. B. Redondo-Campillos)

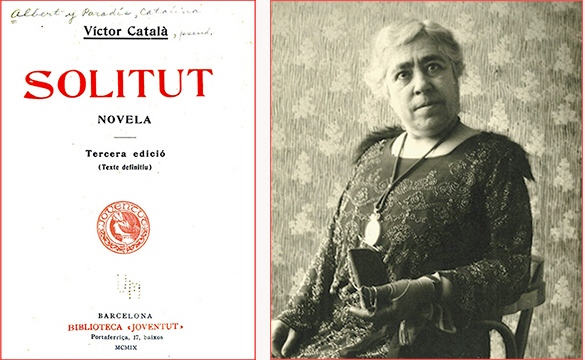

Víctor Català was a Catalan modernist literature novelist, storyteller, playwright, and poet. But Víctor Català was also Caterina Albert i Paradís (L’Escala, Girona, 1869–1966), an extraordinary talented woman writer forced to write under a male pen name. Caterina Albert decided to make herself known as Víctor Català after the publication of the monologue La infanticida (The Infanticide), for which Albert not only received the first prize in the 1898 Jocs Florals literary contest, but also an enormous backlash after the jury knew that the author was a woman. Amid the Catalan intellectual and bourgeois society of the late 19th century, Caterina Albert questions maternity as the main purpose of womanhood in the most dramatic and violent way. Víctor Català/Caterina Albert was probably the first unconscious feminist of Catalan literature.

In her magnum opus, Solitut (1905) or Solitud, first a serialized novel in the literary magazine Joventut and published later as a book, the writer follows the spiritual and life journey of Mila, a woman that moves to a remote rural environment, with a practically absent husband. In an extremely rough landscape — where the mountain becomes another character in the novel and part of Mila herself — she encounters her own sensuality, the guilt provoked by her sexual desire towards a shepherd, the unspeakable brutality of the few people living around her, and the absolute solitude. Far from being weakened because of all of these factors, Mila finds the necessary strength to get by and, finally, makes a life-changing decision.

It is 1905 and Caterina Albert depicts through Mila in Solitud the overly harsh women’s situation in a male rural society. Its novelty lies in that the writer provides the main character with the determination to overcome her disgrace. Mila transgresses the patriarchy system and takes control of her own life, and Caterina Albert transgresses the rules of a male literary society and writes whatever she wants to write. With Solitud the recognition of Víctor Català as a brilliant writer was unanimous: “the most sensational event ever seen in modern Catalan literature” in the words of critic Manuel de Montoliu (introduction to Víctor Català’s Obres Completes, Barcelona: Selecta, 1951).

Despite her success, Caterina Albert was considered a threat to the Noucentisme literary movement, due to her opposition to the group’s ideological agenda. After the publication of Solitud, Víctor Català published her second and last novel, Un film (3.000 metres) in 1926 and rather sporadically, some collections of short stories up to 1944. The author retired from the literary activity and died in her hometown, L’Escala, after having decided to spend the last 10 years of her life in bed.

Contribution by Ana-Belén Redondo-Campillos

Lecturer, Department of Spanish & Portuguese

Title: Solitut

Title in English: Solitude

Author: Víctor Català (pseudonym for Caterina Albert i Paradís), 1869-1966

Imprint: Barcelona : Biblioteca Joventut, 1909.

Edition: 3rd edition

Language: Catalan

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Michigan)

URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015029495648

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Serialized edition published across eight issues in April 2015 in Joventut: periódich catalanista: literatura, arts, ciencias. Barcelona : [publisher not identified], 1900-1906.

- Solitud. Barcelona : Edicions 62, 1979.

- Solitud. 1oth ed. Barcelona: Edicions de la Magrana, 1996.

- Solitud. 20th ed. Barcelona : Selecta, 1980. valoració crítica per Manuel de Montoliu.

- Solitude: A Novel. Columbia, La: Readers International, 1992. translated from the Catalan with a preface by David H. Rosenthal.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Joventut: periódich catalanista: literatura, arts, ciencias

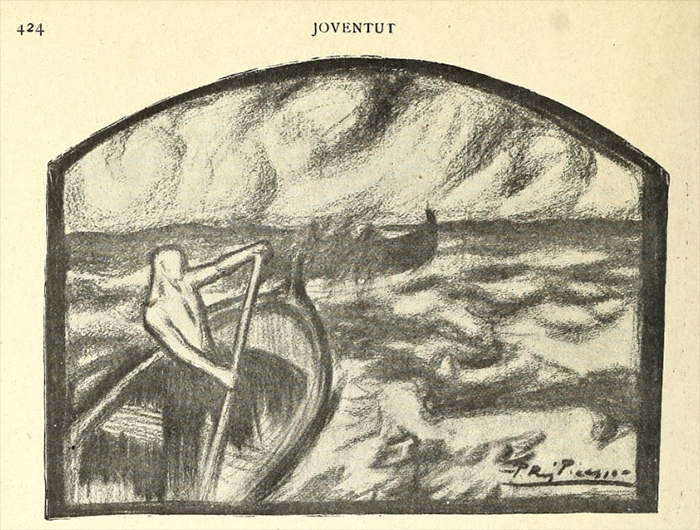

Few books and journals in the Library stay in the same place forever. Berkeley’s copy of the renowned Art Nouveau periodical, Joventut published between 1900 and 1906 and directed by Alexandre de Riquer and Lluís Vía under the auspices of the “Unio Catalanista” has recently migrated from the Art History/Classics Library to The Bancroft Library for safekeeping. Antiquarian bookdealer Peter Bernett describes the journal as “a major forum for the presentation and reviews of ‘modernista’ literature, criticism, theater, music, and visual art in Barcelona and greater Catalonia, as well as discussing current aesthetic trends in Europe.” An extension of the Renaixença cultural and literary movement with inspiration from the Pre-Raphaelites, it featured cutting edge art, architecture and literature. In its first year of publication it was the first review to reproduce a work by Picasso. The ornamental golden binding was inspired by Aubrey Beardsley’s The Yellow Book. Catalan poets, novelists and playwrights such as Jacint Verdaguer, Joaquim Ruyra, and Victor Català — who will soon be featured in The Languages of Berkeley online exhibition —were among the regular contributors.

Joventut has been digitized separately by the Biblioteca de Catalunya and the Getty Research Institute, available through the HathiTrust Digital Library and The Internet Archive.

DH+Lib: Building and Preserving Collections for Digital Humanities Research

DH+LIB: BUILDING AND PRESERVING COLLECTIONS FOR DIGITAL HUMANITIES RESEARCH

Wednesday, April 17th, 9:30 – 11:00 AM

Doe 180

This session will feature panelists building collections and tools for local digital humanities projects. Kathryn Stine, manager for digital content development and strategy at the California Digital Library, will talk about building web archive collections through collaboration, preparing these collections for discovery and use, and tapping the research potential of the resulting captured content and data. Mary Elings, Head of Technical Services for The Bancroft Library, will talk about the role libraries can play in developing research-ready digital collections to facilitate emerging research methods. And Gisèle Tanasse, Film & Media Services Librarian at the Library, will discuss her role in Shakespeare’s Staging, a DH project to help digitize, preserve, and make accessible Shakespeare performances from UC Berkeley students.

DH Fair 2019

http://ucberk.li/dhfair

2019 DH Fair Library Committee

Stacy Reardon, Chair

Lynn Cunningham

Mary Elings

Jeremy Ott

Liladhar Pendse

Claude Potts

Ana Hatherly Bibliography + Conference/Symposium + Talk

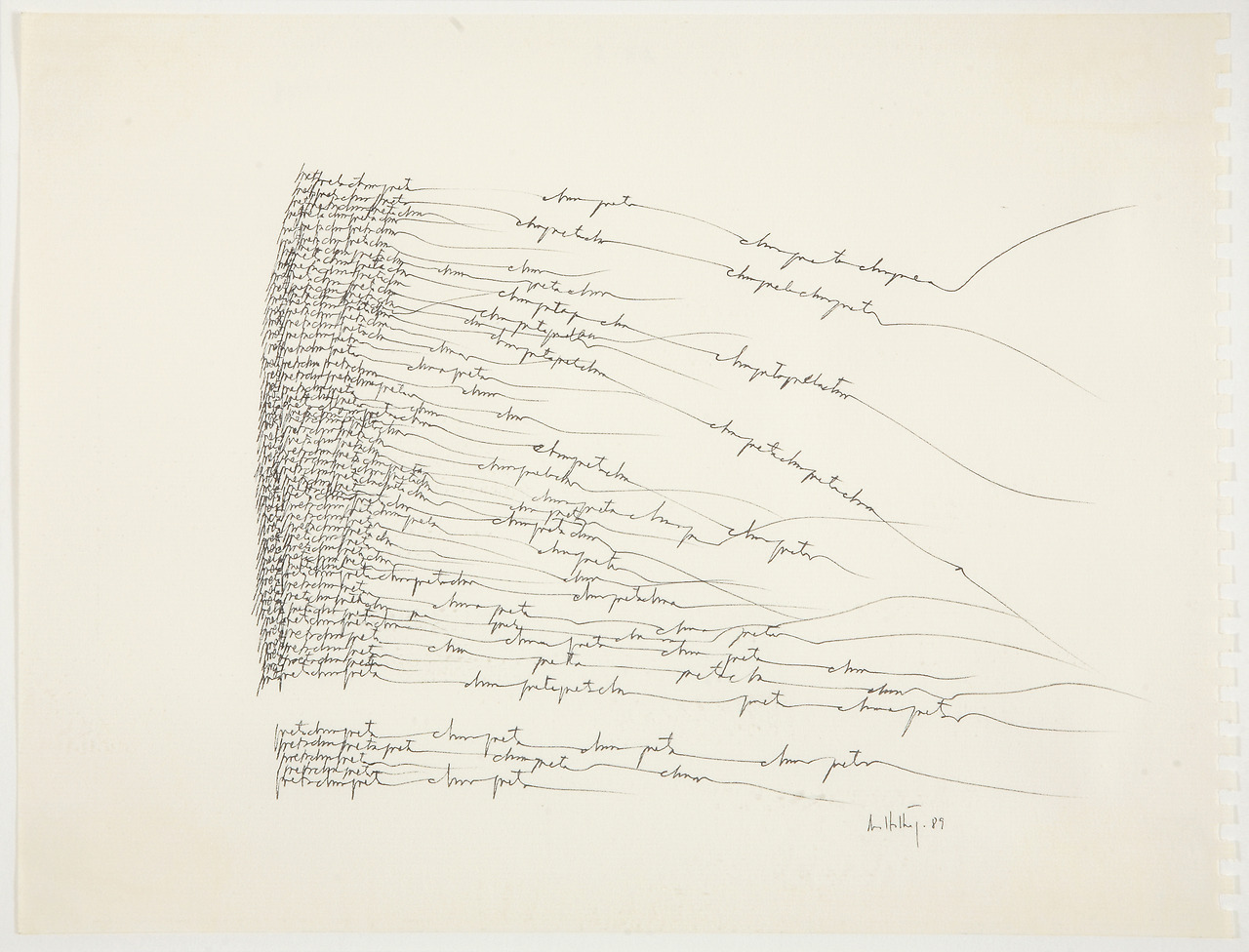

In anticipation of the conference/symposium on Portuguese visual artist/poet/scholar/filmmaker Ana Hatherly (1929-2015), we’ve assembled a bibliography of works authored by and about her in the Berkeley Library. Hatherly was one of the pioneers of the experimental poetry and literature movement in Portugal and already well-known in Europe before earning her PhD at Berkeley in 1986. Many of the books in the collection came to the Library through her dissertation advisor Arthur Askins who maintained close contact with her after she returned to Portugal. Other books were acquired more recently through the support of the Portuguese Studies Program in the Institute of European Studies (IES) and from donors such as retired Berkeley librarian AnneMarie Mitchell.

Between the lines: Tradition and Plasticity in Ana Hathery | Entrelinhas: tradição e plasticidade em Ana Hatherly, which will take place this Friday, March 22 in Stephens Hall, is the third conference/symposium since IES and the Camões Institute in Lisbon inaugurated the Catédra Ana Hatherly, or Chair, in Portuguese Studies in 2017. Tomorrow morning, Patrícia Lino who is currently a Camões lecturer at UC Santa Barbara will give a talk in English on the poetry of Ana Hatherly in Barrows Hall that is free and open to the public.

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)