Tag: BL Indo-European Romance

Romanian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

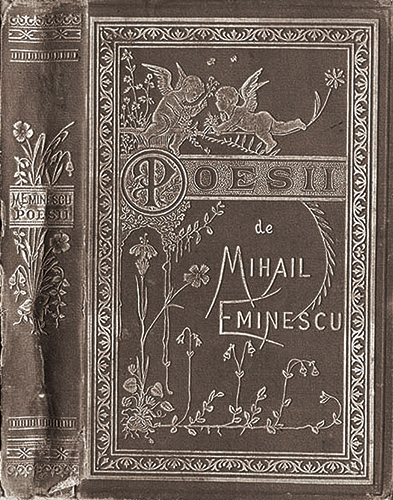

Mihail Eminescu, pseudonym of Mihail Eminovici, (1850-1889), was a poet who transformed both the form and content of Romanian poetry, creating a school of poetry that strongly influenced Romanian writers and poets in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Eminescu was educated in the Germano-Romanian cultural centre of Cernăuţi (now Chernovtsy, Ukraine) and at the universities of Vienna and Berlin, where he was influenced by German philosophy and Western literature. In 1874, he was appointed school inspector and librarian at the University of Iaşi but soon resigned to take up the post of editor in chief of the conservative paper Timpul. His literary activity came to an end in 1883, when he suffered the onset of a mental disorder that led to his death in an asylum.

Eminescu’s talent was first revealed in 1870 by two poems published in Convorbiri literare, the organ of the Junimea society in Iaşi. Other poems followed, and he became recognized as the foremost modern Romanian poet. Mystically inclined and of a melancholy disposition, he lived in the glory of the Romanian medieval past and in folklore, on which he based one of his outstanding poems, “Luceafărul” (1883; “The Evening Star”). Eminescu’s poetry has a distinctive simplicity of language, a masterly handling of rhyme and verse form, a profundity of thought, and a plasticity of expression which affected nearly every Romanian writer of his own period and after. His poems have been translated into several languages, including an English translation in 1930, but chiefly into German. Among his prose writings, apart from many studies and essays, the best-known are the stories “Cezara” and “Sărmanul Dionis” (1872).[1]

Romanian, or Rumanian, is one of the Romance languages that is spoken in Eastern Europe, principally in Romania and the Republic of Moldova. It evolved in very different circumstances from its western sister languages such as Spanish and Italian, and was profoundly affected by the Orthodox Church, the Greek and Slavonic languages, and the Ottoman Empire. It has a lexical affinity with Old Church Slavonic.[2] For the latter half of the 20th century, UC Berkeley had a very active program in Romanian. The Russian-born Romance etymologist and philologist Yakov Malkiel, who taught at Berkeley for over 55 years, mentored students who specialized in Romanian linguistics. In 1947, he became founding editor of the prestigious journal Romance Philology which is still published today. ProQuest’s Dissertation & Theses lists more than 227 doctoral dissertations from UC Berkeley that are related in one way or another to Romania and the Romanian language.[3] However in light of funding cuts, Romanian has not been taught at Berkeley in over two years. Graduate students in the interdisciplinary Romance Languages and Literatures (RLL) program may choose Romanian as one of their languages.[4]

Contribution by Liladhar Pendse

Librarian for East European and Central Asian Studies, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- “Mihail Eminescu: Romanian Poet” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. (accessed 5/1/20)

- Price, Glanville. Encyclopedia of the Languages of Europe. Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 1998.

- Proquest Dissertations & Theses (accessed 5/1/20)

- Romance Languages and Literatures, UC Berkeley (accessed 5/1/20)

- Cimpoi, Mihai (coord.), 2020, Eminescu—Opere (vol. I-VIII), Editura Gunivas.On the matter of the assassination and those involved:

- Lepuş, Miruna, 2021, Dosarele de interdicţie ale lui Mihai Eminescu, Editura Cartex.

- Barbu, Constantin, 2008, Codul invers, Editura Sitech.

- Georgescu, Nicolae, 2014, Boala şi moartea lui Eminescu, Editura Floare Albastră.

- Georgescu, Nicolae, 2011, Eminescu: ultima zi la Timpul, Editura ASE.

- Vuia, Ovidiu, 1997, Despre boala şi moartea lui Mihai Eminescu—studiu patografic, Editura Făt-Frumos.

On the matter of the birthdate:

- Marin, I.D., 1979, Eminescu la Ipoteşti, Editura Junimea.

- Ştefanelli, Teodor V., 1983, Amintiri despre Eminescu, Editura Junimea.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Poezii complecte

Title in English: Complete Poems

Author: Eminescu, Mihai, 1850-1889.

Imprint: Iași, Editura librărieĭ frațiĭ Șaraga [188-?].

Edition: n/a

Language: Romanian

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (Harvard University)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100545314

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Poezii / M. Eminescu ; antologie, prefață și tabel cronologic de George Gană ; ilustrați de Dumitru Verdeș. București : Editura Minerva, 1999.

- Poezii / M. Eminescu ; ediție critică de D. Murărașu. București : Editura Minerva, 1982. v.1-3

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

French

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Si c’est ici le meilleur des mondes possibles, que sont donc les autres?

If this is the best of all possible worlds, what are the others like?

— Voltaire, Candide, ou, l’Optimisme (trans. Burton Raffel)

Voltaire, né François-Marie Arouet (1694-1778), was a French philosopher who mobilized the power of Enlightenment principles in 18th-century Europe more than any other thinker of his day. Born into a prosperous bourgeois Parisian family, his father steered him toward law, but he was intent on a literary career. His tragedy Oedipe, which premiered at the Comédie Française in 1718, brought him instant financial and social success. A libertine and a polemicist, he was also an outspoken advocate for religious tolerance, pluralism and freedom of speech, publishing more than 2,000 works in all possible genres during his lifetime. For his bluntness, he was locked up in the Bastille twice and exiled from Paris three times.[1] Fleeing royal censors, Voltaire fled to London in 1727 where he, despite arriving penniless, spent two and a half years hobnobbing with nobility as well as writers such as Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift.[2]

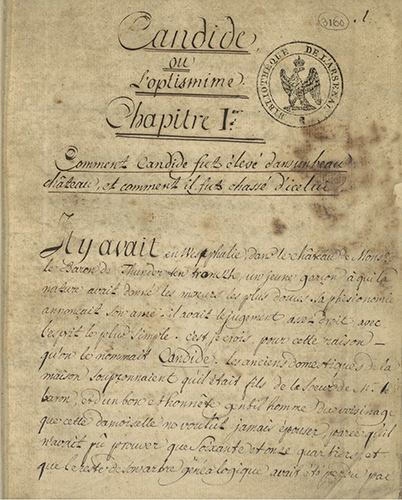

After his sojourn in Great Britain, he returned to the Continent and lived in numerous cities (Champagne, Versaille, Amsterdam, Potsdam, Berlin, etc.) before settling outside of Geneva in 1755 shortly after Louis XV banned him from Paris. “It was in his old age, during the 1760s and 1770s,” writes historian Robert Darnton, “that he wielded his second and most powerful weapon, moral passion.”[3] Early in 1759, Voltaire completed and published the satirical novella Candide, ou l’Optimisme (“Candide, or Optimism”) featured in this entry. In 1762, he published Traité sur la tolerance (“Treatise on Tolerance”), which is considered one of the greatest defenses of religious freedom and human rights ever composed. Soon after its publication, the American and French Revolutions began dismantling the social world of aristocrats and kings that we now refer to as the Ancien Régime.[4]

With Candide in particular, Voltaire is credited with pioneering what is called the conte philosophique, or philosophical tale. Knowing it would scandalize, the story was published anonymously in Geneva, Paris and Amsterdam simultaneously and disguised as a French translation by a fictitious Mr. Le Docteur Ralph. The novella was immediately condemned for its blasphemy and subversion, yet within weeks sold 6,000 copies within Paris alone.[5] Royal censors were unable to keep up with the proliferation of illegal reprints, and it quickly became a bestseller throughout Europe.

Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726) is considered one of its clearest precursors in both form and parody. Candide is the name of the naive hero who is tutored by the optimistic philosophy of Pangloss, who claims that “all is for the best in this best of all possible worlds” only to be expulsed in the first few pages from the opulent chateau in which he grew up. The story unfolds as Candide travels the world and encounters unimaginable human suffering and catastrophes. Voltaire’s satirical critique takes aim at religion, authority, and the prevailing philosophy of the time, Leibnizian optimism.

While the classical language of Candide is more than 260 years old, it is easy enough to comprehend today. As the lingua franca across the Continent, French was accessible to a vast French-reading public since gathering strength as a literary language since the 16th century.[6] However, no language stays the same forever and French is no exception. Old French, which is studied by medievalists at Berkeley, covers the period up to 1300. Middle French spans the 14th and 14th centuries and part of the early Renaissance when the study of French language was taken more seriously. Modern French emerged from one of the two major dialects known as langue d’oïl in the middle of the 17th century when efforts to standardize the language were taking shape. It was then that the Académie Française was established in 1635.[7] One of its members, Claude Favre de Vaugelas, published in 1647 the influential volume, Remarques sur la langue françoise, a series of commentaries on points of pronunciation, orthography, vocabulary and syntax.[8]

At UC Berkeley, scholars have been analyzing Candide and other French texts in the original since the university’s founding. The Department of French may have the largest concentration of French speakers on campus, and French remains like German, Spanish, and English one of the principal languages of scholarship in many disciplines. Demand for French publications is great from departments and programs such as African Studies, Anthropology, Art History, Comparative Literature, History, Linguistics, Middle Eastern Studies, Music, Near Eastern Studies, Philosophy, and Political Science. The French collection is also vital to interdisciplinary Designated Emphasis PhD programs in Critical Theory, Film & Media Studies, Folklore, Gender & Women’s Studies, Medieval Studies, and Renaissance & Early Modern Studies.

UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library is home to the most precious French holdings, including medieval manuscripts such as La chanson de geste de Garin le Loherain (13th c.) and dozens of incunables. More than 90 original first editions by Voltaire can be located in these special collections, including La Henriade (1728), Mémoires secrets pour servir à l’histoire de Perse (1745) Maupertuisiana (1753), L’enfant prodigue: comédie en vers dissillabes (1753) and a Dutch printing of Candide, ou, l’Optimisme (1759). Other noteworthy material from the 18th century overlapping with Voltaire include the Swiss Enlightenment and the French Revolutionary Pamphlet collections.

Contribution by Claude Potts

Librarian for Romance Language Collections, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Davidson, Ian. Voltaire. New York: Pegasus Books, 2010. xviii

- Ibid.

- Darnton, Robert. “To Deal With Trump, Look to Voltaire,” New York Times (Dec. 27, 2018).

- Voltaire. Candide or Optimism. Translated by Burton Raffel. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

- Davidson, 291.

- Levi, Anthony. Guide to French Literature. Chicago: St. James Press, c1992-c1994.

- Kors, Alan Charles, ed. Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment. Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Ibid.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Candide, ou L’optimisme (Manuscrit La Vallière)

Title in English: Candide, ou L’optimisme (La Vallière Manuscript)

Author: Voltaire, 1694-1778

Imprint: La Vallière (Louis-César, duc de). Ancien possesseur, 1758.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: French

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Gallica (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, 3160)

URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b520001724

Other online editions:

- Candide, ou l’Optimisme , traduit de l’allemand de M. le docteur Ralph. Paris: Lambert, 1759. (Gallica)

- Candide, ou l’Optimisme. Première Partie 1. Édition revue, corrigée et augmentée par l’auteur. Aux Delices, 1763.(Gallica)

- Candide, ou l’Optimisme, traduit de l’allemand de M. le docteur Ralph. Seconde partie. Aux Delices, 1761. (Gallica)

- Candide ou L’optimisme. Préface de Francisque Sarcey; illustrations de Adrien Moreau. Paris: G. Boudet, 1893. (Gallica)

- Candide, ou, L’optimisme. Illustré de trente-six compositions dessinées et gravées sur bois par Gérard Cochet. Paris: Les Editions G. Crès et Cie, 1921. (HathiTrust)

- Candide, or Optimism. Translated into English by Burton Raffel. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005. (ebrary-UCB access only)

- Candide / Voltaire. [United States]: Tantor Audio: Made available through hoopla, 2006. ebook and audiobook (OverDrive-UCB access only)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Candide, ou, l’Optimisme / traduit de l’allemand de Mr. le docteur Ralph. Amsterdam: Marc-Michel Rey, MDCCLIX [1759].

- Candide, ou, L’optimisme. Édition présentée, établie et annotée par Frédéric Deloffre. Paris: Gallimard, 2003.

- Candide. [Graphic novel] Interventions graphiques de Joann Sfar. Rosny: Éditions Bréal, 2003.

- Candide, or Optimism. Translated and edited by Theo Cuffe with an introduction by Michael Wood. New York : Penguin Books, 2005.

- Candide, ou L’optimiste. [Graphic novel] Scénario, Gorian Delpâture & Michel Dufranne; dessin, Vujadin Radovanovic; couleur, Christophe Araldi & Xavier Basset. Paris: Delcourt, 2013.

- Candide or, Optimism: The Robert M. Adams Translation, Backgrounds, Criticism. Edited by Nicholas Cronk. New York : W. W. Norton & Company, 2016.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Portuguese

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Ó mar salgado, quanto do teu sal

São lágrimas de Portugal!

Quando virás, ó Encoberto,

Sonho das eras portuguez,

Tornar-me mais que o sopro incerto

De um grande anceio que Deus fez?

O salty sea, so much of whose salt

Is Portugal’s tears!

When will you come home, O Hidden One,

Portuguese dream of every age,

To make me more than faint breath

Of an ardent, God-created yearning?

(Trans. Richard Zenith, Message)

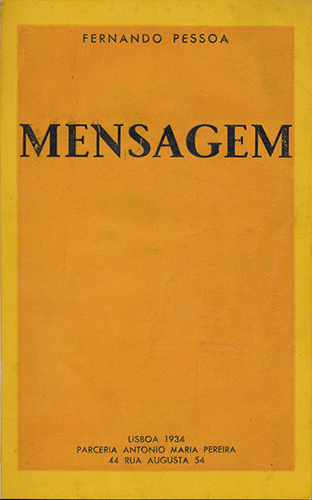

Living in a paradoxical era of artistic experimentalism and political authoritarianism, Fernando António Nogueira Pêssoa (1888-1935) is considered Portugal’s most important modern writer. Born in Lisbon, he was a poet, writer, literary critic, translator, publisher and philosopher. Most of his creative output appeared in journals. He published just one book in his lifetime in his native language Mensagem (“Message”). In the same year this collection of 44 poems was published, António Salazar was consolidating his Estado Novo (“New State”) regime, which would subjugate the nation and its colonies in Africa for more than 40 years. Encouraged to submit Mensagem by António Ferro, a colleague with whom he previously collaborated in the literary journal Orpheu (1915), Pessoa was awarded the poetry prize sponsored by the National Office of Propaganda for the work’s “lofty sense of nationalist exhaltation.”[1]

Because of its association with the Salazar’s dictatorship, Mensagem was regarded as a national monument but also as something reprehensible. Translator Richard Zenith describes it as a “lyrical expansion on The Lusiads, Camões’ great epic celebration of the Portuguese discoveries epitomized by Vasco de Gama’s inaugural voyage to India.”[2] At the same time, it traces an intimate connection to the world at large, or rather, to various worlds (historical, psychological, imaginary, spriritual) beginning with the circumscribed existence of Pessoa as a child. Longing for the homeland, as in The Lusiads, is an undisputed theme of Pessoa’s verses as he spent most of his childhood in Durham, South Africa, with his family before returning to Portugal in 1905.

Pessoa wrote in Portuguese, English, and French and attained fame only after his death. He distinguished himself in his poetry and prose by employing what he called heteronyms, imaginary characters or alter egos written in different styles. While his three chief heteronyms were Alberto Caeiro, Ricardo Reis and Álvaro de Campos, scholars attribute more than 70 of these fictitious alter egos to Pessoa and many of these books can be encountered in library catalogs sometimes with no reference to Pessoa whatsoever. Use of identity as a flexible, dynamic construction, and his consequent rejection of traditional notions of authorship and individuality prefigure many of the concerns of postmodernism. He is widely considered one of the Portuguese language’s greatest poets and is required reading in most Portuguese literature programs.[3]

According to Ethnologue, there are over 234 million native Portuguese speakers in the world with the majority residing in Brazil.[4] Portuguese is the sixth most natively spoken language on the planet and the third most spoken European language in terms of native speakers.[5] Instruction in Portuguese language and culture has occurred primarily within the Department of Spanish & Portuguese. Since 1994, UC Berkeley’s Center for Portuguese Studies in collaboration with institutions in Portugal brings distinguished scholars to campus, sponsors conferences and workshops, develops courses, and supports research by students and faculty.

Contribution by Claude Potts

Librarian for Romance Language Collections, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Preface to Richard Zenith’s English translation Message. Lisboa: Oficina do Livro, 2016.

- Ibid.

- Portuguese (PORTUG) – Berkeley Academic Guide (accessed 2/4/20)

- Ethnoloque: Languages of the World (accessed 2/4/20)

- CIA World Factbook (accessed 2/4/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Mensagem

Title in English: Message

Author: Pessoa, Fernando, 1885-1935.

Imprint: Lisbon: Parceria António Maria Pereira, 1934.

Edition: 1st

Language: Portuguese

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal

URL: http://purl.pt/13966

Other online editions:

- Mensagem / Fernando Pessoa. – 1934. – [70] p. ; 22,2 x 14,7 cm. From Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal (BNP), http://purl.pt/13965.

- Mensagem. 1a ed. Lisboa : Pereira, 1934.

- Mensagem. Print facsimile from original manuscript in BNP. Lisboa : Babel, 2010.

- Mensagem. Comentada por Miguel Real ; ilustrações, João Pedro Lam. Lisboa : Parsifal, 2013.

- Mensagem : e outros poemas sobre Portugal. Fernando Cabral Martins and Richard Zenith, eds. Porto, Portugal : Assírio & Alvim, 2014.

- Mensagem. Translated into English by Richard Zenith. Illustrations by Pedro Sousa Pereira. Lisboa : Oficina do Livro, 2008

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Italian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

It took centuries before Italy could codify and proclaim Italian as we know it today. The canonical author Dante Alighieri, was the first to dignify the Italian vernaculars in his De vulgari eloquentia (ca. 1302-1305). However, according to the Tuscan poet, no Italian city—not even Florence, his hometown—spoke a vernacular “sublime in learning and power, and capable of exalting those who use it in honour and glory.”[1] Dante, therefore, went on to compose his greatest work, the Divina Commedia in an illustrious Florentine which, unlike the vernacular spoken by the common people, was lofty and stylized. The Commedia (i.e. Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso) marked a linguistic and literary revolution at a time when Latin was the norm. Today, Dante and two other 14th-century Tuscan poets, Petrarch and Boccaccio, are known as the three crowns of Italian literature. Tuscany, particularly Florence, would become the cradle of the standard Italian language.

In his treatise Prose della volgar lingua (1525), the Venetian Pietro Bembo champions the Florentine of Petrarch and Boccaccio about 200 years earlier. Regardless of the ardent debates and disagreements that continued throughout the Renaissance and beyond, Bembo’s treatise encouraged many renowned poets and prose writers to compose their works in a Florentine that was no longer in use. Nevertheless, works continued to be written in many dialects for centuries (Milanese, Neapolitan, Sicilian, Sardinian, Venetian and many more), and such is the case until this day. But which language was to become the lingua franca throughout the newly formed Kingdom of Italy in 1861?

With Italy’s unification in the 19th century came a new mission: the need to adopt a common language for a population that had spoken their respective native dialects for generations.[2] In 1867, the mission fell to a committee led by Alessandro Manzoni, author of the bestselling historical novel I promessi sposi (The Betrothed, 1827). In 1868, he wrote to Italy’s minister of education Emilio Broglio that Tuscan, namely the Florentine spoken among the upper class, ought to be adopted. Over the years, in addition to the widespread adoption of The Betrothed as a model for modern Italian in schools, 20th-century Italian mass media (newspaper, radio, and television) became the major diffusers of a unifying national language.

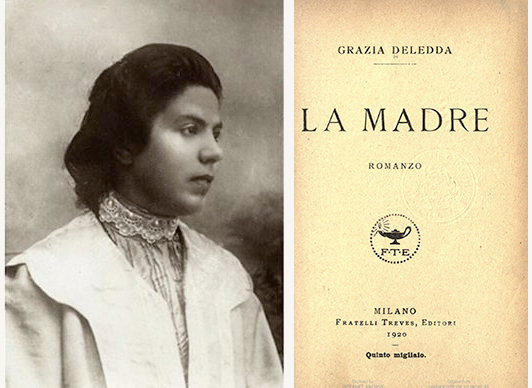

Grazia Maria Cosima Deledda (1871-1936), the author featured in this essay, is one of the millions of Italians who learned standardized Italian as a second language. Her maternal language was Logudorese Sardo, a variety of Sardinian. She took private lessons from her elementary school teacher and composed writing exercises in the form of short stories. Her first creations appeared in magazines, such as L’ultima moda between 1888 and 1889. She excelled in Standard Italian and confidently corresponded with publishers in Rome and Milan. During her lifetime, she published more than 50 works of fiction as well as poems, plays and essays, all of which invariably centered on what she knew best: the people, customs and landscapes of her native Sardinia.

The UC Berkeley Library houses approximately 265 books by and about Deledda as well as our digital editions of her novel La madre (The Mother). It was originally serialized for the newspaper Il tempo in 1919 and published in book form the following year. Deledda recounts the tragedy of three individuals: the protagonist Maria Maddalena, her son and young priest Paulo, and the lonely Agnese with whom Paulo falls in love. The mother is tormented at discovering her son’s love affair with Agnese. Three English translations of La madre have appeared, however, it was the 1922 translation by Mary G. Steegman (with a foreword by D.H. Lawrence) that was most influential in providing Deledda with international renown.

Deledda received the 1926 Nobel Prize for Literature “for her idealistically inspired writings which, with plastic clarity, picture the life on her native island and with depth and sympathy deal with human problems in general.”[3] To this day, she is the only Italian female writer to receive the highest prize in literature. Here are the opening lines of Deledda’s speech in occasion of the award conferment in 1927:

Sono nata in Sardegna. La mia famiglia, composta di gente savia ma anche di violenti e di artisti primitivi, aveva autorità e aveva anche biblioteca. Ma quando cominciai a scrivere, a tredici anni, fui contrariata dai miei. Il filosofo ammonisce: se tuo figlio scrive versi, correggilo e mandalo per la strada dei monti; se lo trovi nella poesia la seconda volta, puniscilo ancora; se va per la terza volta, lascialo in pace perché è un poeta. Senza vanità anche a me è capitato così.

I was born in Sardinia. My family, composed of wise people but also violent and unsophisticated artists, exercised authority and also kept a library. But when I started writing at age thirteen, I encountered opposition from my parents. As the philosopher warns: if your son writes verses, admonish him and send him to the mountain paths; if you find him composing poetry a second time, punish him once again; if he does it a third time, leave him alone because he’s a poet. Without pride, it happened to me the same way. [my translation]

The Department of Italian Studies at UC Berkeley dates back to the 1920s. Nevertheless, Italian was taught and studied long before the Department’s foundation. “Its faculty—permanent and visiting, present and past—includes some of the most distinguished scholars and representatives of Italy, its language, literature, history, and culture.” As one of the field’s leaders and innovators both in North America and internationally, the Department retains its long-established mission of teaching and promoting the language and literature of Italy and “has broadened its scope to include multiple disciplinary and interdisciplinary perspectives to view the country, its language, and its people” from within Italy and globally, from the Middle Ages to the present day.[4]

Contribution by Brenda Rosado

PhD Student, Department of Italian Studies

Source consulted:

- Dante Alighieri, De Vulgari Eloquentia, Ed. and Trans. Steven Botterill, p. 41

- Mappa delle lingue e gruppi dialettali d’italiani, Wikimedia Commons (accessed 12/5/19)

- From Nobel Prize official website: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1926/summary

See also the award presentation speech (on December 10, 1927) by Henrik Schück, President of the Nobel Foundation: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1926/ceremony-speech (accessed 12/5/19) - Department of Italian Studies, UC Berkeley (accessed 12/5/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: La madre

Title in English: The Woman and the Priest

Author: Deledda, Grazia, 1871-1936

Imprint: Milano : Treves, 1920.

Edition: 1st

Language: Italian

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: HathiTrust (University of California)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006136134

Other online editions:

- La madre. 1st ed. Milano : Treves, 1920. (Sardegna Digital Library)

- The Woman and the Priest. Translated into English by M.G. Steegman; foreword by D.H. Lawrence. London, J. Cape, 1922. (HathiTrust)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- La madre. 1st ed. Milano : Treves, 1920.

- La Madre : (The woman and the priest), or, The mother. Translated into English by M.G. Steegman; foreword by D.H. Lawrence; with an introduction and chronology by Eric Lane. London : Dedalus, 1987.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Occitan

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

A Lamartine:

Te consacre Mirèio : es moun cor e moun amo,

Es la flour de mis an,

Es un rasin de Crau qu’emé touto sa ramo

Te porge un païsan.

To Lamartine :

To you I dedicate Mirèio: ‘tis my heart and soul,

It is the flower of my years;

It is a bunch of Crau grapes,

Which with all its leaves a peasant brings you. (Trans. C. Grant)

On May 21, 1854, seven poets met at the Château de Font-Ségugne in Provence, and dubbed themselves the “Félibrige” (from the Provençal felibre, whose disputed etymology is usually given as “pupil”). Their literary society had a larger goal: to restore glory to their language, Provençal. The language was in decline, stigmatized as a backwards rural patois. All seven members of the Félibrige, and those who have taken up their mantle through the present day, labored to restore the prestige to which they felt Provençal was due as a literary language. None was more successful or celebrated than Frédéric Mistral (1830-1914).

Mirèio, which Mistral referred to simply as a “Provençal poem,” is composed of 12 cantos and was published in 1859. Mirèio, the daughter of a wealthy farmer, falls in love with Vincèn, a basketweaver. Vincèn’s simple yet noble occupation and Mirèio’s modest dignity and devotion mark them as embodiments of the country virtues so prized by the Félibrige. Mirèio embarks on a journey to Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, that she might pray for her father to accept Vincèn. Her quest ends in tragedy, but Mistral’s finely drawn portraits of the characters and landscapes of beloved Provence, and of the implacable power of love still linger. C.M. Girdlestone praises the regional specificity and the universality of Mistral’s oeuvre thus: “Written for the ‘shepherds and peasants’ of Provence, his work, on the wings of its transcendant loveliness, reaches out to all men.”[1]

Mistral distinguished himself as a poet and as a lexicographer. He produced an authoritative dictionary of Provençal, Lou tresor dóu Felibrige. He wrote four long narrative poems over his lifetime: Mirèio, Calendal, Nerto, and Lou Pouemo dóu Rose. His other literary work includes lyric poems, short stories, and a well-received book of memoirs titled Moun espelido. Frédéric Mistral won a Nobel Prize in literature in 1904 “in recognition of the fresh originality and true inspiration of his poetic production, which faithfully reflects the natural scenery and native spirit of his people, and, in addition, his significant work as a Provençal philologist.”[2]

Today, Provençal is considered variously to be a language in its own right or a dialect of Occitan. The latter label encompasses the Romance varieties spoken across the southern third of France, Spain’s Val d’Aran, and Italy’s Piedmont valleys. The Félibrige is still active as a language revival association.[3] Along with myriad other groups and individuals, it advocates for the continued survival and flowering of regional languages in southern France.

Contribution by Elyse Ritchey

PhD student, Romance Languages and Literatures

Source consulted:

- Girdlestone, C.M. Dreamer and Striver: The Poetry of Frédéric Mistral. London: Methuen, 1937.

- “Frédéric Mistral: Facts.” The Nobel Prize. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1904/mistral/facts. (accessed 11/12/19)

- Felibrige, http://www.felibrige.org (accessed 11/12/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Mirèio

Title in English: Mirèio / Mireille

Author: Mistral, Frédéric, 1830-1914

Imprint: Paris: Charpentier, 1861.

Edition: 2nd

Language: Occitan with parallel French translation

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Gallica (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k64555655

Other online editions::

- An English version (the original crowned by the French academy) of Frédéric Mistral’s Mirèio from the original Proven̨cal under the author’s sanction. Avignon : J. Roumanille, 1867. HathiTrust

- Mireille, poème provençal avec la traduction littérale en regard. Paris, Charpentier, 1898. HathiTrust

- Mirèio : A Provençal poem. Translated into English by Harriet Waters Preston. London, T.F. Unwin, 1890. Internet Archive (UC Riverside)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Mireille : poème provençal. Traduit en vers français par E. Rigaud. Paris : Librairie Hachette, 1881.

- Mireio : pouemo prouvencau, avec la traduction littérale en regard. Paris : Charpentier, 1888.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Spanish (Europe)

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

If you walk down the street in many parts of the world and ask a stranger who fought the windmills, they would most probably answer Don Quixote. But they would not necessarily know the name of its author, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1547-1616). This not-so-prolific dramaturge, poet and novelist has nonetheless had a major impact on the development of Western literature, influencing his English contemporary William Shakespeare, 19th-century French author Gustave Flaubert, and 20th-century Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges, just to name a few.

Cervantes did not come to prominence until much later in his life. His experiences as a soldier, a captive and a witness to the struggles of the Spanish empire shaped his distinctive oeuvre: a literary world of experimentation, as can be seen in his Exemplary Novels (1613), a world in which possibilities of reconciliation between conflictive individuals, ideals and desires remained hollow, inconclusive and, in many cases, without avail. Among other factors, what distinguishes Cervantes’ literary production is its unclassifiable nature, making it hard to try and fit the works in their presumed corresponding genre. One good example is his posthumous work The Travails of Persiles and Sigismunda (1616), where the Byzantine novel is mutilated to such an extent that, at points, it becomes almost unrecognizable.

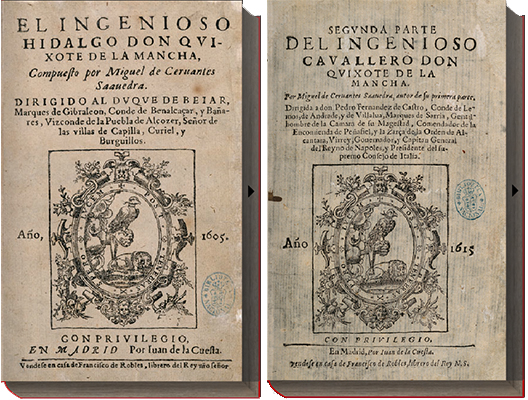

Yet this unfittedness is most evident in Don Quixote (Part I published in 1605; Part II in 1615). The confusion between reality and fiction, the untrustworthiness of the multiple narrators, the intentional errors and misnomers, the three-dimensionalism of Don Quixote’s squire, Sancho, who has a love-hate relationship with his master, the utter destruction of the chivalric world, and the encounter with oppressed minorities are but some of the factors that have undoubtedly contributed to the sustained appeal of Don Quixote. The protagonist, an old man who “loses his mind” reading novels of chivalry, was, in Western literature, a pioneering self-proclaimed “hero.” He offers and imposes his help unto people who rarely take him seriously. Moreover, he only becomes popular, within his diegetic world, when in Part II he is defined by others as a caricature. This caricature remains dominant in the collective imaginary of readers, as can be seen, for example, in Picasso’s well-known depiction of the character.

Although most masterpieces ultimately attempt to challenge a comfortable experience of reading where we readily identify with fictitious characters; Don Quixote still manages to attract the empathy of its readers who may or may not closely identify with the knight-errant. Don Quixote is beaten up, both physically and metaphorically, yet his innocent, albeit selfish at times, intentions have ultimately won the hearts of a diverse audience over the centuries.

Today, the Spanish language, or Castilian as it is referred to in Europe, has grown from around 14 million speakers at the time of Cervantes to 477 million native speakers worldwide. It is now the second most used language for international communication and the most studied languages on the planet.[1] At Berkeley, Spanish is one of the most widely used languages for scholarship after English, particularly in departments such as Anthropology, Comparative Literature, Ethnic Studies, Film & Media, Gender & Women’s Studies, History, Linguistics, Political Science, and Rhetoric. Interdisciplinary graduate programs in Latin American Studies, Medieval Studies, Romance Languages and Literature, and Medieval and Early Modern Studies also require reading of original texts in Spanish.

Nasser Meerkhan, Assistant Professor

Department of Near Eastern Studies & Department of Spanish & Portuguese

Source consulted:

- Elias, D. José Antonio. Atlas historico, geográfico y estadístico de España y sus posesiones de ultramar. Barcelona : Imprenta Hispana, 1848; Hernández Sánchez Barbara, Mario. “La población hispanoamericana y su distribución social en el siglo XVIII,” Revista de estudios políticos, no.78 (1954); López, Morales H, and El español: una lengua viva. Informe 2017. Madrid : Arco Libros, S.L. : El Instituto, 2017.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha

Author: Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de, 1547-1616.

Imprint: En Madrid : por Iuan de la Cuesta, 1605, 1615.

Edition: 1st

Language: Spanish (Europe)

Language Family: Indo-European

Source: Biblioteca Nacional de España

URL: http://quijote.bne.es/libro.html (requires Flash)

Other online editions:

- El ingenioso hidalgo don Quixote de la Mancha / compuesto por Miguel de Ceruantes Saauedra. En Madrid : por Iuan de la Cuesta, 1605.

- Segunda parte del ingenioso cauallero don Quixote de la Mancha / por Miguel de Ceruantes Saauedra, autor de su primera parte. En Madrid : por Iuan de la Cuesta, 1615.

- The History of Don Quixote. Translated into English by J.W. Clark. Illustrated by Gustave Doré. New York, P.F. Collier, 1871 .

Select print editions at Berkeley:

Considered to be the most translated work every written, the Library has editions in French, German, Hebrew, Armenian, Quechua, and more. The earliest and best illustrated editions reside in The Bancroft Library.

- El ingenioso hidalgo don Quixote de la Mancha. Burgaillos. Published Impresso con licencia, en Valencia : En casa de Pedro Patricio Mey : A costa de Iusepe Ferrer mercader de libros, delante la Diputacion, 1605.

- Segunda parte del ingenioso cauallero don Quixote de la Mancha. En Valencia : En casa de Pedro Patricio Mey, junto a San Martin : A costa de Roque Sonzonio mercader de libros, 1616.

- Vida y hechos del ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha. Nueva edicion, corregida y ilustrada con 32 differentes estampas muy donosas, y apropriadas à la materia. Amberes, Por Henrico y Cornelio Verdussen, 1719.

- El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha / por Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra ; obra adornada de 125 estampas litográficas y publicada por Masse y Decaen, impresore litógrafos y editores, callejon de Santa Clara no 8. México : Impreso por Ignacio Cumplido, calle de los Rebeldes num. 2, 1842.

- Don Quixote / Miguel de Cervantes ; a new translation by Edith Grossman ; introduction by Harold Bloom. New York : Ecco, c2003.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Portuguese (Brazil)

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

“A imaginação foi a companheira de toda a minha existência, viva, rápida, inquieta, alguma vez tímida e amiga de empacar, as mais delas capaz de engolir campanhas e campanhas, correndo.”

“Imagination has been the companion of my whole existence — lively, swift, restless, at times timid and balky, most often ready to devour plain upon plain in its course.” (trans. Helen Caldwell p. 41, Dom Casmurro)

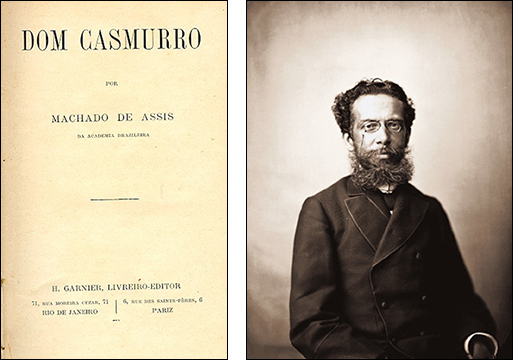

The novel Dom Casmurro is considered a masterpiece of literary realism and one of the most significant works of fiction in all of Latin American literature. The late Brazilian literary critic Afrânio Coutinho called it possibly one of the best works written in the Portuguese language, and it has been required reading in Brazilian schools for more than a century.[1] At UC Berkeley, generations of students in literature courses have been enjoying the rich complexity of this work of prose since the 1950s when the author began receiving recognition worldwide. Indelibly influenced by French social realists such as Honoré de Balzac, Gustave Flaubert and Émile Zola, Dom Casmurro is a sardonic social critique of Rio de Janeiro’s bourgeoisie. The satirical novel takes the reader on a terrifying journey into a mind haunted by jealousy via an unreliable first-person narrative told by Bento Santiago (Bentinho) who suspects his wife Capitú of adultery.

Dom Casmurro was written by multiracial and multilingual Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis (1864-1908) who was an essayist, literary critic, reporter, translator, government bureaucrat. He was most venerated for his short stories, plays, novellas, and novels which were all set in his milieu of Rio de Janeiro. The son of a freed slave who had become a housepainter and a Portuguese mother from the Azores, he grew up in an affluent household under a generous patroness where his parents were agregados (domestic servants).[2] A prodigy of sorts, he began writing at an early age, and quickly ascended the socio-cultural ladder in a country that did not abolish slavery until 1888 with the Lei Áurea (Golden Act).[3] At the center of a group of well-known poets and writers, Machado founded the Academia Brasileira de Letras (Brazilian Academy of Letters) in 1896, became its first president, and was perpetually reelected until his death in 1908.[4] “Even more remarkable than Machado’s absence from world literature,” wrote Susan Sontag, “is that he has been very little known and read in Latin America outside Brazil — as if it were still hard to digest the fact that the greatest author ever produced in Latin America wrote in the Portuguese, rather than the Spanish, language.”[5]

With a population of over 210 million, Brazil has eclipsed Portugal and its former colonies in Africa and Asia and now constitutes more than 80 percent of the world’s Portuguese speakers. Portuguese is the sixth most natively spoken language globally.[6] While European Portuguese (EP) is considered a less commonly taught language in American universities, this is not the case for Brazilian Portuguese (BP) where it has become increasingly popular. The Modern Language Association’s recently released study on languages taught in U.S. institutions, ranked Portuguese as the eleventh most taught language.[7] BP and EP are the same language but have been evolving independently, much like American and British English, since the 17th century. Today, the linguistic variations (phonetics, phonology, syntax, morphology, semantics, pragmatics) are so stark that a non-fluent observer might mistake the two for entirely different languages. In 1990, all Portuguese-language countries signed the Acordo Ortográfico da Língua Portuguesa — a treaty to standardize spelling rules across the Lusophone world — which went into effect in Brazil in 2009 and in Portugal in 2016.[8]

At Berkeley, Brazilian literature is offered for all periods and levels of study through the Department of Spanish and Portuguese’s Luso-Brazilian Program directed by Professor Candace Slater.[9] Her research centers on traditional narrative and cordel ballads, and she was awarded the Ordem de Rio Branco in 1996 — the highest honor the Brazilian government accords a foreigner — and in 2002, the Ordem de Merito Cultural. Other Brazilianists in the department include professors Natalia Brizuela and Nathaniel Wolfson. Graduate students with an interest in Brazil who are part of the Hispanic Language and Literatures (HLL), Romance Language and Literatures (RLL), and Latin American Studies programs delve into all aspects of the nation’s history, culture, and language.[10]

Contribution by Claude Potts

Librarian for Romance Language Collections, Doe Library

Sources consulted

- Coutinho Afrânio. Machado de Assis na literatura brasileira. Academia Brasileira de Letras, 1990.

- “More on Machado,” Brown University Library’s Brasiliana Collection. (accessed 7/19/19)

- Rodriguez, Junius P. Encyclopedia of Emancipation and Abolition in the Transatlantic World. Armonk, NY: Sharpe Reference, 2007.

- Preface to Dom Casmurro: A Novel by Machado de Assis. Translated by Helen Caldwell. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966, c1953.

- Sontag, Susan. “Afterlives: the Case of Machado de Assis,” New Yorker (April 29, 1990).

- CIA World Factbook (accessed 7/19/19)

- Modern Language Association of America. Enrollments in Languages Other Than English in United States Institutions of Higher Education, Summer 2016 and Fall 2016: Final Report (June 2019). (accessed 7/19/19)

- Vocabulário Ortográfico da língua portuguesa. 5a ed. São Paulo, SP : Global Editora ; Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil : Academia Brasileira de Letras, 2009; and Academia das Ciências de Lisboa. Vocabulário ortográfico atualizado da língua portuguesa. Lisboa : Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda, 2012.

- Portuguese (PORTUG) – Berkeley Academic Guide (accessed 7/26/19)

- Hispanic Languages & Literatures, Romance Languages and Literatures, Latin American Studies, UC Berkeley (accessed 7/25/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Dom Casmurro

Title in English: Dom Casmurro : novel

Author: Machado de Assis, Joaquim Maria, 1839-1908.

Imprint: Rio de Janeiro; Paris: Garnier, 1899.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Portuguese

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil

URL: http://acervo.bndigital.bn.br/sophia/index.asp?codigo_sophia=4883

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- O romance Dom Casmurro de Machado de Assis / Maximiano de Carvalho e Silva. Niterói : Editora da UFF, 2014. Includes the reproduction of the 1899 edition.

- Dom Casmurro. Ilustrações, Carlos Issa ; posfácio, Hélio Guimarães. São Paulo, SP : Carambaia, 2016.

- Dom Casmurro : A Novel. Translated from the Portuguese by John Gledson ; with a foreword by John Gledson and an afterword by João Adolfo Hansen. Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Dom Casmurro: A Novel by Machado de Assis. Translated by Helen Caldwell. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966, c1953.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Catalan

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

I don’t want you to confine my thinking to facts and agreed formulas; I do want, like birds, the liberated wings to fly at any time, now to the right, now to the left, through the space full of infinite and invisible routes; I do not want extraneous nuisances, harmful limits that impose me a path beforehand. I want to be entirely master of myself and not a slave of alien forces, insofar as human, are miserable and failing. – Víctor Català (Caterina Albert), Insubmissió (1947)

(Trans. A. B. Redondo-Campillos)

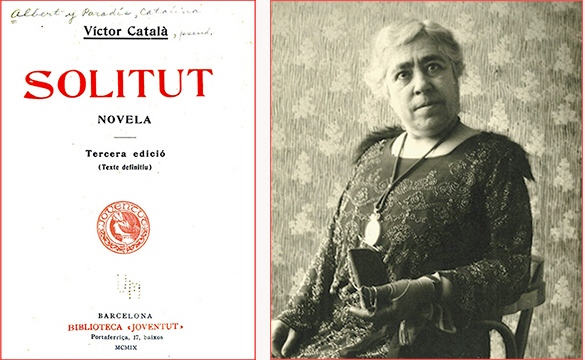

Víctor Català was a Catalan modernist literature novelist, storyteller, playwright, and poet. But Víctor Català was also Caterina Albert i Paradís (L’Escala, Girona, 1869–1966), an extraordinary talented woman writer forced to write under a male pen name. Caterina Albert decided to make herself known as Víctor Català after the publication of the monologue La infanticida (The Infanticide), for which Albert not only received the first prize in the 1898 Jocs Florals literary contest, but also an enormous backlash after the jury knew that the author was a woman. Amid the Catalan intellectual and bourgeois society of the late 19th century, Caterina Albert questions maternity as the main purpose of womanhood in the most dramatic and violent way. Víctor Català/Caterina Albert was probably the first unconscious feminist of Catalan literature.

In her magnum opus, Solitut (1905) or Solitud, first a serialized novel in the literary magazine Joventut and published later as a book, the writer follows the spiritual and life journey of Mila, a woman that moves to a remote rural environment, with a practically absent husband. In an extremely rough landscape — where the mountain becomes another character in the novel and part of Mila herself — she encounters her own sensuality, the guilt provoked by her sexual desire towards a shepherd, the unspeakable brutality of the few people living around her, and the absolute solitude. Far from being weakened because of all of these factors, Mila finds the necessary strength to get by and, finally, makes a life-changing decision.

It is 1905 and Caterina Albert depicts through Mila in Solitud the overly harsh women’s situation in a male rural society. Its novelty lies in that the writer provides the main character with the determination to overcome her disgrace. Mila transgresses the patriarchy system and takes control of her own life, and Caterina Albert transgresses the rules of a male literary society and writes whatever she wants to write. With Solitud the recognition of Víctor Català as a brilliant writer was unanimous: “the most sensational event ever seen in modern Catalan literature” in the words of critic Manuel de Montoliu (introduction to Víctor Català’s Obres Completes, Barcelona: Selecta, 1951).

Despite her success, Caterina Albert was considered a threat to the Noucentisme literary movement, due to her opposition to the group’s ideological agenda. After the publication of Solitud, Víctor Català published her second and last novel, Un film (3.000 metres) in 1926 and rather sporadically, some collections of short stories up to 1944. The author retired from the literary activity and died in her hometown, L’Escala, after having decided to spend the last 10 years of her life in bed.

Contribution by Ana-Belén Redondo-Campillos

Lecturer, Department of Spanish & Portuguese

Title: Solitut

Title in English: Solitude

Author: Víctor Català (pseudonym for Caterina Albert i Paradís), 1869-1966

Imprint: Barcelona : Biblioteca Joventut, 1909.

Edition: 3rd edition

Language: Catalan

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Michigan)

URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015029495648

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Serialized edition published across eight issues in April 2015 in Joventut: periódich catalanista: literatura, arts, ciencias. Barcelona : [publisher not identified], 1900-1906.

- Solitud. Barcelona : Edicions 62, 1979.

- Solitud. 1oth ed. Barcelona: Edicions de la Magrana, 1996.

- Solitud. 20th ed. Barcelona : Selecta, 1980. valoració crítica per Manuel de Montoliu.

- Solitude: A Novel. Columbia, La: Readers International, 1992. translated from the Catalan with a preface by David H. Rosenthal.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Spanish (Latin America)

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

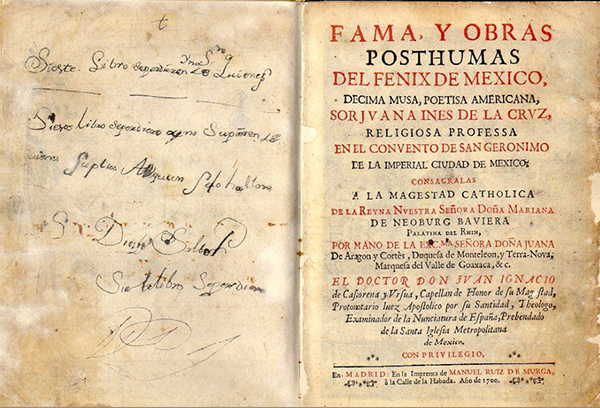

Nun, rebel, genius, poet, persecuted intellectual, and proto-feminist, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (Nepantla 1648-Mexico City 1695) was the most distinguished intellectual in the pre-Independence American colonies of Spain. She was called “Tenth Muse” in her own time and continues to inspire the popular and scholarly imagination. Generations of Mexican schoolchildren have memorized her satirical ballad “Hombres necios que acusáis / a la mujer sin razón… “ (You foolish men who cast all blame on women), and her portrait appears on the 200-peso note. Despite her status as an icon of Mexican culture, an annotated edition of her complete works was not published until the tercentenary of her birth in the mid-1950s, and the complexity of her poetry, prose, and theater was known only by reputation until the second wave of feminism brought scholarly attention to her work in the 1970s. Octavio Paz’s monumental study, Sor Juana, o, Las trampas de la fe (Sor Juana, or The Traps of Faith) appeared in 1982.

An intellectual prodigy brought to the viceregal court of New Spain in her teens, Sor Juana was largely self-taught. In 1669, she entered the convent of San Jerónimo in order to continue her studies. Although women were excluded from the study of theology and rhetoric, she wrote a brilliant critique of a renowned Portuguese cleric’s sermon, and was reprimanded by the Bishop of Puebla, who wrote under a female pseudonym. Sor Juana’s “Respuesta a sor Filotea” (1691, “Reply to Sister Philothea”) displayed her erudition in defense of her intellectual passion, arguing that St. Paul’s often-quoted admonition that women should keep silent in church (mulieres in ecclesia taceant), should not prohibit women’s pursuit of knowledge and instruction of young girls. Other significant works include secular and religious theater; philosophical poetry; passionate poems to the noblewomen who were her patrons; and villancicos, sets of songs she was commissioned to write for religious celebrations.

Sor Juana’s long epistemological poem, Primero sueño (First Dream) epitomizes the Creole appropriation of the Baroque and yet she weaves into her poetry and theater a recognition of the humanity of indigenous peoples. While her literary models were European and her poetry was first published in Spain, her works evince an American consciousness in the representation of the violence of the conquest in the loa to El divino Narciso (Divine Narcissus) and her use of Nahuatl in the villancicos.

Contribution by Emilie Bergmann

Professor, Department of Spanish & Portuguese

Title: Fama, y obras póstumas

Title in English: Homage and posthumous works

Author: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1648-1695)

Imprint: Madrid: Manuel Ruiz de Murga, 1700.

Edition: 1st

Language: Spanish (Latin America)

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Universitätsbibliothek, Universität Bielefeld

URL: http://ds.ub.uni-bielefeld.de/viewer/image/1592397/1

Other online editions:

- Inundación castálida, de la única poetisa, musa décima, soror Juana Inés de la Cruz … (Madrid: Juan García Infanzón, 1689) and the first edition of Segundo volumen de las obras de soror Juana Inés de la Cruz (Sevilla: Tomás López de Haro, 1692).

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Critical and annotated editions of the first two volumes of Sor Juana’s work, Inundación Castálida (1689) and Segundo tomo (1693), as well as Fama, y obras póstumas and editions of complete and selected works are available in printed form in The Bancroft Library and the Main Stacks.

- Sor Juana’s complete works were published in four volumes: Obras completas, Alfonso Méndez Plancarte and Alberto G. Salcedo. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1951-57. Many English translations of selected works of Sor Juana’s works are also in OskiCat including those of Alan S. Trueblood, Margaret Sayers Peden, Amanda Powell, and Edith Grossman.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)