Tag: Events

Sign up for the Oral History Center’s Introductory Workshop (March 8)

The UC Berkeley Oral History Center is pleased to announce that applications are open for the 2024 Introductory Workshop!

The OHC is offering online versions of our educational programs again this year.

Introductory Workshop: Friday, March 8 from 8:30 a.m. to 2:30.p.m. Pacific Time, via Zoom

The 2024 Introduction to Oral History Workshop will be held virtually via Zoom on Friday, March 8, from 8:30 a.m. to 2:30.p.m. Pacific Time, with breaks woven in. Applications are now being accepted on a rolling basis. Please apply early, as spots fill up quickly.

Apply for the Introductory Workshop.

This workshop is designed for people who are interested in an introduction to the basic practice of oral history and in learning best practices. The workshop serves as a companion to our more in-depth Advanced Oral History Summer Institute held in August.

The workshop focuses on the foundational elements of oral history, including methodology and ethics, practice, and recording. It will be taught by our seasoned oral historians and include hands-on practice exercises. Everyone is welcome to attend the workshop. Prior attendees have included community-based historians, teachers, genealogists, public historians, and students in college or graduate school.

Tuition is $150. We are offering a limited number of participants a discounted tuition of $75 for students, independent scholars, or those experiencing financial hardship. If you would like to apply for discounted tuition, please indicate this on your application form and we will send you more information. Please note that the OHC is a soft-money research office of the university, and as such receives precious little state funding. Therefore, it is necessary that this educational initiative be a self-funding program. Unfortunately, we are unable to provide financial assistance to participants other than our limited number of scholarships. We encourage you to check in with your home institutions about financial assistance; in the past we have found that many programs have budgets to help underwrite some of the costs associated with attendance. We will provide receipts and certificates of completion as required for reimbursement.

Applications are accepted on a rolling basis. We encourage you to apply early, as spots fill up quickly.

If you have specific questions, please contact Shanna Farrell (sfarrell@library.berkeley.edu)

About the Oral History Center

UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center, or the OHC, is one of the oldest oral history programs in the world. We produce carefully researched, recorded, and transcribed oral histories and interpretive materials for the widest possible use. Since 1953 we have been preserving voices of people from all walks of life, with varying perspectives, experiences, pursuits, and backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public.

Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

EVENT Bancroft Roundtable: Land, Wealth and Power: Digitizing the California Land Case Files, 1852-1892

November 17, 2022 | Noon | Register via Zoom

Presented by Adrienne Serra, Digital Project Archivist, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, with an introduction by Principal Investigator Mary Elings, Interim Deputy Director, Associate Director, and Head of Technical Services, The Bancroft Library

In 2021, The Bancroft Library launched a large-scale digitization project to preserve and provide online access to more than 127,000 pages of California Land Case Files dating from ca. 1852 to 1892. These records tell an important story about the use and distribution of land, as well as social and legal justice in California following statehood in 1850, when all Spanish and Mexican land grants holders were required to prove their land claims in court. A lengthy process of litigation followed, which resulted in many early Californians losing their land. The Land Case Files are heavily used by current land owners, genealogists, historians, and environmentalists to understand the land, its uses, and ownership over time. The digitization project, Land, Wealth and Power: Private Land Claims in California, ca. 1852 to 1892 (Mary Elings, Principal Investigator), was awarded a 2019 Digitizing Hidden Special Collections and Archives: Amplifying Unheard Voices grant. Digital Project Archivist Adrienne Serra will discuss the collection and the project, including the challenges of preparing and imaging fragile materials under pandemic restrictions, and plans for future community engagement projects.

See you there! As always, this talk will also be recorded and added to our Youtube channel.

Best,

Christine & José Adrián

Resource: Bancroft Roundtables online

The Bancroft Library has updated its website with links to online presentations of most of the past Bancroft Roundtable events. These include:

September 16th

Expanding Access to WWII Japanese American Incarceree Data Using Machine Learning

Presented by Marissa Friedman, Digital Project Archivist, The Bancroft Library

Watch online on YouTube

October 21st

A Good Drink: In Pursuit of Sustainable Spirits

Presented by Shanna Farrell, Interviewer, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library

Watch online on YouTube

November 18th

The Photographs of the Northwest Boundary Survey, 1857 to 1862

Presented by James Eason, Principal Archivist, Pictorial Collection, The Bancroft Library

Watch online on YouTube

Event: Documenting the Japanese American Incarceration through Narratives and Data. June 2

Documenting the Japanese American Incarceration Through Narratives and Data

June 2 | 2-4 p.m. | Doe Library, Morrison Library

In person and online: ucberk.li/bancroft-symposium

Hosted by The Bancroft Library, Berkeley Library

The event is posted in the UC Berkeley Events Calendar here.

Session 1: Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project: Is Healing Possible?

2:00 pm – 3:00 pm

This session explores the Oral History Center’s ongoing Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project that documents and disseminates the ways in which intergenerational trauma and healing occurred after the U.S. government’s incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. This project examines and compares how private memory, creative expression, place, and public interpretation intersect at the Manzanar and Topaz prison camps in California and Utah. This panel will include discussion with interviewers, and it will feature conversations with a clinical psychologist and specialist in intergenerational trauma who advises on the project and leads healing circles for narrators, as well as a narrator who was interviewed for the project.

Roger Eardley-Pryor, Interviewer, the Oral History Center

Shanna Farrell, Interviewer, the Oral History Center

Dr. Lisa Nakamura, clinical psychologist and Topaz descendant

Ruth Sasaki, Topaz Stories Editor

Amanda Tewes, Interviewer, the Oral History Center

Session 2: Giving Data Back to the Community through Computational Scholarship: Two Case Studies Focused on Japanese American Incarceree Records from World War II

3:00 pm – 4:00 pm

This session brings together two in-process projects that are working to encourage computational and ethical access to collections and data. Presenters from The Bancroft Library and Densho will discuss their projects related to records surrounding the forced removal and incarceration of 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry during World War II. The intersectional and positional work of these projects highlights the importance of building new partnerships outside of the archives to create new content and implement community co-curation models to support on-going inquiry, knowledge-building, and exploration around this topic, with implications for vulnerable communities today.

Mary Elings, Interim Deputy Director, The Bancroft Library

Marissa Friedman, Digital Project Archivist, The Bancroft Library

Brian Niiya, Content Director, Densho

Geoff Froh, Deputy Director, Densho

Vijay Singh, CEO, Doxie.AI

These events will be recorded.

Funding for this event was made possible, in part, by grants from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program and The Henri and Tomoye Takahashi Charitable Foundation.

Covid Protocols

We ask that participants comply with all health and safety guidelines and protocols recommended by UC Berkeley. This includes wearing a mask while indoors.

All Audiences

bancroft@library.berkeley.edu, 510-642-3781

If you require an accommodation to fully participate in this event, please contact Amber Lawrence at libraryevents@berkeley.edu or 510-459-9108 at least 7-10 days in advance of the event.

Event: Bancroft Roundtable: A Good Drink: In Pursuit of Sustainable Spirits

ROUNDTABLE: A Good Drink: In Pursuit of Sustainable Spirits

ROUNDTABLE: A Good Drink: In Pursuit of Sustainable Spirits

October 21, 2021

Noon

Register via Zoom

Presented by Shanna Farrell, Interviewer, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library

Shanna Farrell, an interviewer at the Oral History Center, will join the Bancroft Roundtable to discuss her new book, A Good Drink: In Pursuit of Sustainable Spirits. Before she was an oral historian, she was a bartender. She not only mixed drinks and poured spirits, but learned their stories–who made them and how. In A Good Drink, Farrell takes readers on a global journey to meet farmers, distillers, and bartenders who are driving the transformation to sustainable spirits. Along the way, she reveals the urgent need for a sustainable spirits movement, as distilling requires huge volumes of water, bars generate mountains of trash, and crops for spirits are often grown with chemicals that are health hazards and environmental pollutants. Farrell will discuss how she drew on her training as an oral historian to research the environmental issues at hand, meeting and interviewing featured narrators, and the strengths of taking an interdisciplinary approach to tell the story of what’s at stake for sustainable spirits.

What happened at the Building LLTDM Institute

This update is cross-posted from the Building LLTDM blog.

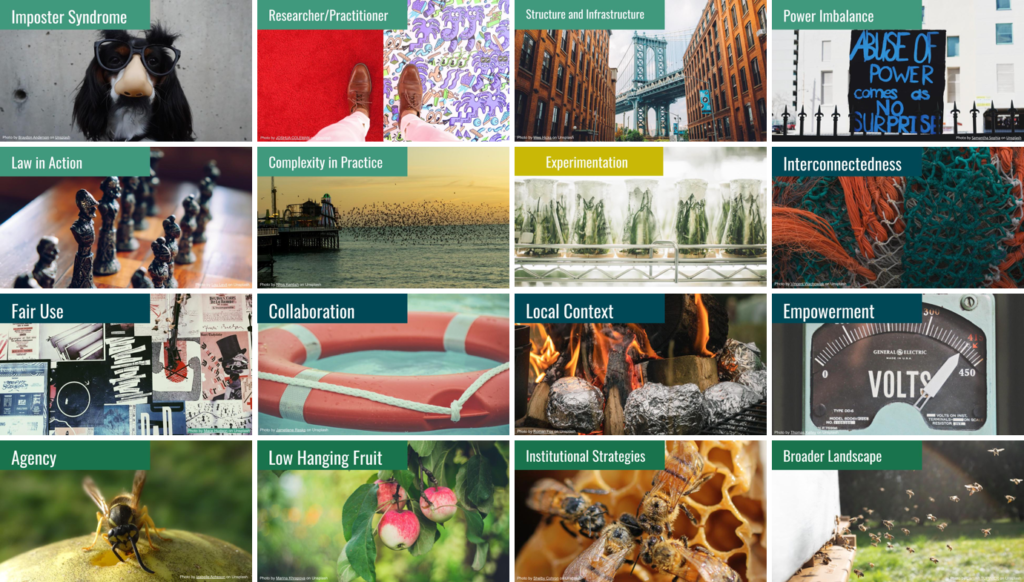

On June 23-26, we welcomed 32 digital humanities (DH) researchers and professionals to the Building Legal Literacies for Text Data Mining (Building LLTDM) Institute. Our goal was to empower DH researchers, librarians, and professional staff to confidently navigate law, policy, ethics, and risk within digital humanities text data mining (TDM) projects—so they can more easily engage in this type of research and contribute to the further advancement of knowledge. We were joined by a stellar group of faculty to teach and mentor participants. Building LLTDM is supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Why was the Institute needed?

Until now, humanities researchers conducting text data mining in the U.S. have had to maneuver through a thicket of legal issues without much guidance or assistance. As an example, take a researcher scraping content about Egyptian artifacts from online sites or databases, or downloading videos about Egyptian tomb excavations, in order to conduct automated analysis about religion or philosophy. The researcher then shares these content-rich data sets with others to encourage research reproducibility or enable other researchers to query the data sets with new questions. This kind of work can raise issues of copyright, contract, and privacy law. It can also raise concerns around ethics, for example, if there are plausible risks of exploitation of people, natural or cultural resources, or indigenous knowledge.

Potential law and policy hurdles do not just deter text data mining research: They also bias it toward particular topics and sources of data. In response to confusion over copyright, website terms of use, and other perceived legal roadblocks, some digital humanities researchers have gravitated to low-friction research questions and texts to avoid making decisions about rights-protected data. When researchers limit their research to such sources, it is inevitably skewed, leaving important questions unanswered, and rendering resulting findings less broadly applicable.

Moving an interactive, design-thinking Institute online

After months of preparation, we had been looking forward to working and learning together at UC Berkeley, but the world had other plans for our Institute. Due to the global health crisis, we had to transform our planned in-person, intensive workshop into an interactive and relevant remote experience.

How did we do this? The pandemic meant we had to transition everything online, which of course presents challenges for a design-thinking framework. We are thrilled that our approach to interactive remote pedagogy was successful! (You can check out the schedule and framework in our Participant Packet.) The substantive content was pre-recorded and delivered in a flipped classroom model. Faculty created a series of short videos, and shared readings relevant to the legal literacies. We also provided the video transcripts and slides to participants to promote accessibility and accommodate multiple learning styles.

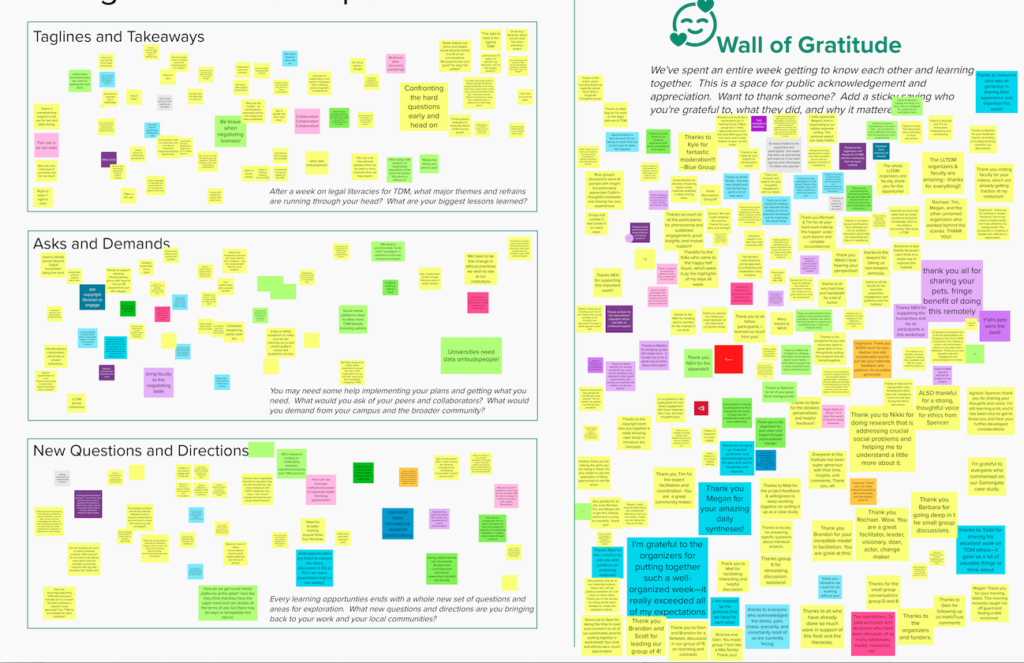

We used Zoom to meet synchronously for discussion in groups of various sizes. We used Slack for asynchronous communication, and interactive tools such as Mural for design thinking exercises like journey mapping so that everyone could live edit and collaborate. We capped each day with a “happy half hour” on Zoom as an informal way to get to know each other a little better, even from afar.

We also relied on an institute moderator and daily writing exercises to reinforce the design-thinking stages and learning outcomes. Each night, we reviewed the participants’ free-writes and began the next morning by reflecting back to the participants the themes from what they had shared.

Reflections on goals: social justice & effective empowerment

One of our priorities for the Institute was to invite a diverse pool of participants, including those involved in social justice research, in order to maximize the public value impact of Building LLTDM. We looked for demonstrated commitments to diversity and equity but could hardly have imagined the breadth and depth of experiences that applicants were willing to share. The selected participants research everything from understanding “place” data from community histories of historic African American settlements to the development of AIDS activist networks in communities of color; to portrayals of autism in literature; and more. Others demonstrated a commitment to bringing back the skills they learn to expand TDM opportunities for students and communities who have traditionally been marginalized or under-resourced. They also came from a variety of institution types, from research advising and support experience, professional roles, levels of experience with TDM, career stages, and disciplinary perspectives.

We are also moved by the participants’ own reflections on the experience. One of the last interactive exercises we hosted during the online Institute was a collective week-in-review discussion, and gratitude wall. We asked the participants to share what they were thankful for, highlighting other participants where possible. So many of the participants wrote about how valuable the learning experience was and how thoughtfully it was put together and delivered.

We can’t express the transformational impact of the week better than the participants, themselves. In Institute evaluation forms, they shared feelings like:

- “This is by far the best organized event that I have ever attended. The content was by far the most substantive. The faculty were by far the most engaged. A+ across the board.”

- “I am so grateful to have had the opportunity to engage with a diverse group of scholars (researchers and professionals)… The deliberately thought through breakdown and mix fostered incredibly valuable discussions and I would hope this kind of framework is used as a best practice for future DH institutes of all kinds going forward. Also, thank you for such an amazing virtual experience which I can only imagine took a tremendous amount of work to coordinate and plan with limited time to shift to an entirely different format–I was overjoyed to critically engage with complex subjects…”

- “This has been phenomenal. I don’t want to qualify it (by adding something like “…for having to be moved online”), because it’s been so, so good: well organized, thoughtful, and human throughout.”

- “There was clearly so much thought, care, and planning that went into the preparation of this institute, and it was an amazing opportunity to learn from a group of people — organizers, faculty, and participants — who all have such deep expertise. The video and readings lists alone are a huge resource, but to be able to process and reflect on that material together with a diverse group of people was really wonderful.”

Next steps, and our own gratitude

What’s next for Building LLTDM? The “Institute” is not over yet; only the 1-week training is complete. The cohort will be meeting again virtually in February 2021 to discuss how implementation of the literacies into our local communities and practices has gone. In the meantime, as the participants bring back the law and policy literacies they’ve learned to their home institutions, we are excited to see several cohort members already organizing their own post-Institute research subgroups, such as those whose TDM work relies heavily on social media content, and others who are exploring how to disseminate the Building LLTDM literacies within other instructional formats and frameworks.

As part of the grant, the project team will also be aggregating the resources from the Institute and developing supplementary material for an Open Educational Resource (OER). We know there is a large community of TDM researchers and professionals who may be interested in or who can benefit from these materials, and the OER will be made available for broad reuse in the public domain.

Thank you to all the participants for their insights and contributions, willingness to share, and flexibility in transitioning to a fully-remote Institute. Thank you to all the faculty for their unmatched legal and policy expertise, ongoing commitment to mentorship, and adaptability in content creation and delivery. And thank you again to the NEH for making such a meaningful experience possible.

Reporting back on Publish or Perish panel discussion at Morrison Library

On Friday, January 31, early career faculty, graduate students, librarians, and others joined us for Publish or Perish Reframed: Navigating the New Landscape of Scholarly Publishing. The event, hosted by the Office of Scholarly Communication Services, aimed to help everyone understand the behind-the-scenes workings of scholarly publishing, especially for the early career researchers and students interested in publishing.

Why are we concerned about the state of scholarly publishing? Things are looking rather sunny for UC authors, who publish nearly 10% of all scholarly literature in the United States. However, there are actually a lot of tensions in the scholarly publishing ecosystem today, and the landscape can be confusing or murky. One of the tensions has to do with access to research, as 85% of journal articles being published each year are still stuck behind paywalls, thus slowing scientific discovery because only people who have subscriptions can access and read it. Subscription prices of commercial scholarly journals continue to increase, while university library collections budgets continue to shrink–further constricting access to knowledge. Another challenge is ongoing publishing expectations: PhD students, post-docs, and young faculty are under ongoing pressure to publish in the most prestigious journals available in order to receive promotion and tenure, even though many of these publishing venues continue to be the most closed and expensive to which libraries subscribe.

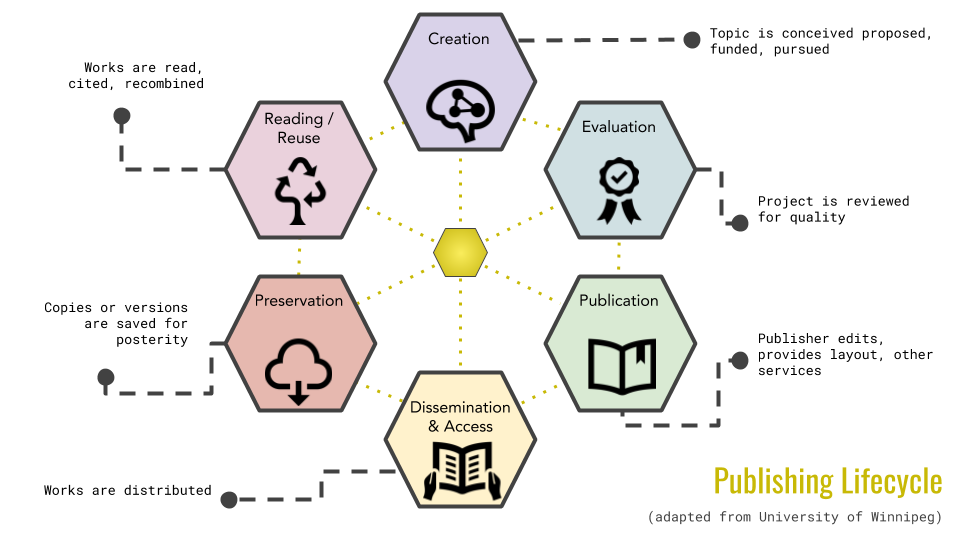

The publishing lifecycle, stakeholder power, and library budgets

Rachael Samberg and Timothy Vollmer from the Office of Scholarly Communication Services kicked off the event by taking a closer look at the publishing lifecycle today. While this process can vary somewhat based on the nature of the research, there are some common aspects, such as (1) reading the works of others and then forming your own research, (2) creating a new knowledge product such as a written article, (3) submitting that work to a publisher which coordinates a peer review process, (4) publishing the work in a scholarly journal, (5) distributing the work via library subscriptions or open access, and (6) preserving the work.

The publishing lifecycle involves many different players, and power is not distributed equally amongst these various participants. For instance:

- The reading public or scholars at other institutions have an interest in reading the outputs of scholarship, but little power in demanding how it’s made available. They can’t vote with their feet and decide not to read a journal article they need for their research, the way you could with a car that was too expensive, and for which an equivalent car might be available from another manufacturer for less.

- The author has an interest in producing good quality work, but is in some ways beholden to needing it to be selected by reputable journals to build reputation and achieve career advancement.

- Universities are interested in recruiting and retaining high profile scholars and students—and also grants and donor funds—and the reception of scholarship created at the institutions affect their ability to do this. The more prestigious the publications, the better this reflects on the universities, so there is some pressure universities can exert over authors about the journals in which their authors should publish.

- Funders like federal agencies and philanthropic foundations want the research they support to make a societal and global impact, and are therefore interested in how that research is disseminated. Funders can require dissemination of work product, but they can’t necessarily interfere with academic freedom about where to publish.

- Libraries want to purchase or license access to the content to provide it to the readers at their universities or institutions. But they’re not the ones creating the content as a way to try to control costs, and further if they refuse to purchase or license content, their authors and universities will be affected

- Scholarly societies are interested in putting out high quality scholarship, but they may also wish to generate enough money to fund not only their publishing efforts but also other society operations like conferences or education—so this limits how “low they can go,” so to speak in terms of the price point for what they publish.

- Most of the market power—at least on the surface—lies with large third party commercial publishers, who stand poised to generate substantial profits in exchange for the opportunity to publish in or read their valued journals.

Many institutions aren’t lucky enough to have the millions of dollars needed to spend on getting subscriptions to high priced journal content. And if they don’t have that money and can’t subscribe, then the people affiliated with that institution can’t read the latest scholarship. In turn, if the institution’s scholars don’t have access to it, then their ability to use it to help them come up with new ideas and insights in their own scholarship is severely limited. So, scientific progress is hampered.

Open access publishing approaches

In order to understand how any stakeholders can encourage an open outcome, we’ve first got to understand what types of open access financial strategies exist. How is OA funded? If we replace the subscription system with OA end products, why would publishers stay in the game? If publishers are going to invest time and effort in publishing, how do they recover costs in an OA universe?

Before we dive into OA funding approaches, one important thing to keep in mind is that publishing a scholarly article or book open access does not mean foregoing peer review or any of the other stringent editorial processes that ensure high quality scholarship. In fact, peer review can be even carried out in more cost effective ways for OA journals. At its core, open access is just an outcome: Scholarship is published online in a way that can be read and used by anyone, and without any financial, legal, or technical barriers other than gaining access to the Internet, itself.

Okay, so on to who gets paid and how. One approach to achieving OA is “green open access.” This “flavor” of OA means that authors or institutions make works that would otherwise only be available via a subscription freely available by depositing certain versions of their scholarship into online repositories, typically institutional repositories run by a researcher’s university (like the UC’s eScholarship), or even a funder repository like the NIH’s PubMed Central.

The version that can be deposited depends in part on the specific terms of the publication agreement the author signs with the publisher. You might be wondering, why on earth does it matter what publication agreement says? Well, in exchange for the publisher agreeing to publish a journal article—they often demand that authors relinquish some or all relevant rights to share or reuse the work. So, in order to publish in most commercial journals, the author must transfer their copyright to the journal. And unless their publication agreement reserves certain rights for the author, the copyright transfer means the author will no longer retain the necessary rights to publicly share the final article—even on their own course website or institutional repository.

So, if authors assign all their rights to publishers, why are they permitted to deposit certain versions of their work in a repository? There are two reasons. First, many publishers’ agreements now provide authors with permission to self archive what’s called the “post-print”— the final peer-reviewed article but that lacks the publisher’s final copy-editing and formatting. Second, institutional OA policies preemptively secure the rights for universities to host works notwithstanding the language of author publication agreements. These policies can attach to articles before an author ever signs a publication agreement.

This is what the UC’s Open Access Policy does. As a UC author, you have a right to deposit your post-print of your article into UC’s institutional repository called eScholarship at the time of publication. The UC takes a license to display the peer-reviewed version of your work, such that any publication agreement you later sign is subject to the UC’s pre-existing right..

There’s also “gold open access.” Gold OA means that what the publisher puts out online on its website—immediately upon publication of the article, whether in print or online—is free access to the final, publisher-version of the article. Typically these articles are shared under a Creative Commons license. Some gold OA publishers recoup production costs via charges for authors to publish (“article processing charges” or “book processing charges”) rather than having readers (or libraries) pay to access and read it. In general, gold OA is a system in which the author pays, rather than the reader paying. At the same time, the fees to be paid for publishing don’t actually have to be paid by the author. They can be covered by various sources, such as: research accounts, research grants, the university, the monies the libraries previously were spending on subscriptions to that journal, scholarly societies, and consortia. (Read on for the program the UC Berkeley Library runs to cover these fees.)

There’s also a type of gold open access that does not involve APCs. Here, the publisher provides permanent and free access to readers with neither author fees nor reader fees. Typically a society, organization, government, or endowment would be necessary to cover the cost of publication.

Empowering universities and authors

We explored what UC Berkeley is doing to leverage these open access models to make scholarship more available. The UC is pursuing a wide array of strategies to improve access to research, including many outlined in the Pathways to Open Access toolkit. To be sure, UC authors have been publishing their articles open access for years, and UC was one of the early institutions with a post-print, green open access policy. But Pathways to Open Access analyzed a panoply of additional funding strategies, and made recommendations for a plurality of approaches.

One example of a new strategy being pursued is negotiating transformative agreements. These types of arrangements have been supported by the UC systemwide faculty senate library committee, who pushed ahead the goal of replacing subscription-based publishing with open access by releasing a declaration of rights and principles to transform scholarly communication. These principles are now guiding the UC libraries in pursuing transformative publishing agreements.

The UC’s goal with transformative agreements is to both changing subscription agreements into agreements that enable open access publishing, and also reduce how much we are spending on the publishing enterprise to begin with. It’s important to emphasize that transformative agreements are just one of the ways the UC campuses and the UC Berkeley library are pursuing open access.

The University of California has been exploring different types of flexible models for transformative agreements. For instance, the agreement the UC has pursued with Cambridge University Press is a multi-payer model, where both libraries and authors (if they have grant funds) contribute to the open access publishing fee.

From the author’s perspective, the Cambridge transformative workflow attempts to minimize intrusion into the publishing process, while still working to incorporate authors into the payment process in some form so they understand the costs of publishing in a new landscape. Authors still choose their journal, submit their manuscript to the journal, and pass through the peer review process as normal; we’re not asking them to change how they do any of those things, especially how they select a journal. Once a manuscript is accepted by a journal with a publisher with whom we have a transformative agreement, then the author is asked to choose whether to publish open access or to opt out of the agreement and publish closed access. Of course, the Library prefers for authors to publish open access, and our intention is to make that the default option, but we don’t require this.

Assuming an author chooses to publish open access, they will be asked to coordinate payment of an APC. In general, this APC is discounted from the list price that the publisher may currently be charging. The library commits to paying a portion of every open access fee. We then ask the author whether they have research funding available which may be used to pay for publication. If they do, then the author pays the remainder of the OA fee. If they do not have research funding available for this purpose, then the library pays the remainder of the fee on the author’s behalf. In this way, authors engage with the payment process, and they contribute a portion of the cost if they have funding available to do so. However, authors without research funding are not disadvantaged, and we never ask an author to reach into their own pockets to make a payment.

Even if the UC hasn’t entered into a transformative agreement with a publisher, there are many other opportunities for authors to get involved in impactful OA decision-making. We discussed that one thing UC Berkeley authors can do right now is to take part in the existing UC open access publishing mechanisms, such as by depositing post-prints in eScholarship an. We also mentioned the UC Berkeley Library program called the Berkeley Research Impact Initiative (BRII) that covers up to $2500 of an APC an author is charged for publishing in a fully open access journal.

Another way authors can empower themselves as scholars is by retaining various rights in the publishing process. Making smart decisions about copyright can help scholarly authors maximize the impact of their research by promoting greater readership and reuse . In most cases, the author of an article is the copyright holder, and authors maintain their copyright to the scholarship until they transfer all or certain rights to a publisher. Now, the publisher might ask for a full transfer of copyright. But as an author you don’t necessarily have to just sign the agreement a publisher presents to you. You can ask for an alternative wording, and sometimes they immediately just send you their alternate agreement with that change already baked in. Some publishers take a different approach through which authors keep their copyright and instead agree to share their work under an open license. For example, copyright in all Public Library of Science articles stays with the authors, but the authors agree to share the work under an open license, in this case the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. This license permits unrestricted use and sharing provided the original author and source are credited. In the end, authors have choices to make, both in managing their rights through the author agreement, or even pursuing full open access journals that leverage open licensing.

Challenges in Publishing for Promotion and Tenure

Benjamin Hermalin, Vice Provost for the Faculty, discussed some of the tensions within scholarly publishing as they relate to promotion and tenure, and provided some advice to new authors in making their way through the publication process. While the Office of the Vice Chancellor for the Faculty reviews all outside letters in each tenure and promotion submission, he said there’s still some conservatism in how tenure and review committees assess a scholar’s publishing outputs and impact. Hermalin advised young researchers to take a measured approach by understanding the particular requirements and publishing practices for their specific field, and aim for publishing several publications in high quality journals relevant to their area.

Of course, the question keeps coming up: How does a researcher get published in the top journals? No one knows the complete answer to this, but authors need to be systematic, and diligent. Hermalin advocated that it’s more important to work toward becoming a major contributor to one or two areas than to be a minor contributor to several fields of research.

Hermalin also talked about some of the challenges researchers face in determining when to publish. He noted that while an author shouldn’t send something out before they’re ready, they also shouldn’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good: getting the research off your desk in a timely fashion is best for your academic profile and chances for tenure down the road. He also suggested that authors not split their scholarly output too thinly: it’s better to publish a few substantial, in-depth papers on a particular topic than several separate publications that individually cover too little of the research endeavor.

Open publishing: A View from the Faculty

Philip Stark, Professor of Statistics and Associate Dean of the Division of Math and Physical Sciences, provided an on-the-ground perspective of open science, OA publishing, and how he deals with copyright and publishing contracts with commercial publishers. Stark showed several examples of how he marks up publishing agreements since he no longer gives any publisher an exclusive right to publish. He also showed how to strike language and amend it to retain copyright and other publishing rights, and said in his experience, most publishers have accepted these changes.

Professor Stark discussed one paper that he published open access through help from BRII. The paper analyzed gender bias in student evaluations, and Stark and his co-authors wanted it to be open access. But Philip was concerned that if they published it in an open access publication, his co-authors—who were a junior faculty and PhD student at the time—might not get as much recognition or impact from the paper than if they were to shoot for publishing in one of journals considered to be “high impact” under certain standards.j. However, the initial fears about publishing on ScienceOpen were unfounded, as the paper has since been widely accessed, cited, and freely downloaded over 70,000 times. Stark said he earned a much bigger impact publishing open access there than if it’d been published in a commercial journal.

Finally, Professor Stark discussed academic freedom in relation to faculty publishing choices. While many think the concept of academic freedom means that researchers are privileged with the ability to work on what they find interesting and important without outside pressure from the university administration, the reality is that faculty—especially early career researchers—are under ongoing pressure to publish in journals that will secure them tenure, or to obtain grants to support their (or their students’) research. In this sense, faculty publishing decisions are driven more by economic forces than the principle of academic freedom. Stark said that this temptation to publish in the most prestigious journal to advance your career is a persistent moral hazard because it challenges the more noble perceptions we have about academic pursuits and how the work of academics benefits science, and the public interest.

Certainly, no one had all the answers for simplifying the complexities of scholarly publishing, but by understanding the driving forces and power dynamics, early career authors can make informed choices that will carry their scholarship far both in impact and in their professional advancement.

February 6: Art for your Apartment

Wednesday, February 6

5:00 – 6:00 p.m.

Morrison Library

The best way to appreciate art is to live with it!

Come see and learn about the Graphic Arts Loan Collection. This is framed art prints you can bring home and hang on your wall for the school year.

Event takes place in the historic Morrison Room (housed within the Doe Library). A brief presentation will be followed by ample time to browse representative works and initiate the borrowing process.

Prints comprise a survey of movements and artists – from Impressionism to Cubism, and from Rembrandt to Miro.

December 5: Lunch Poems with Margaret Ross

Thursday, December 5

Thursday, December 5

12:10 p.m. – 12:50 p.m.

Morrison Library in Doe Library

Admission Free

Margaret Ross is the author of A Timeshare. Her poems and translations appear in The New Republic, The Paris Review, and POETRY. Her honors include a Fulbright arts grant, a VSC/Luce Chinese Poetry & Translation Fellowship, and a Wallace Stegner Fellowship. She currently teaches at Stanford University where she is a Jones Lecturer.

Off the to races with the Office of Scholarly Communication Services

Photo by Goh Rhy Yan on Unsplash

Photo by Goh Rhy Yan on Unsplash

It’s that time of year again. Students are back on campus, classes are in session, and the Library’s Office of Scholarly Communication Services is here to help everyone hit the ground running with resources and workshops on digital publishing, copyright, and open access to research.

As usual, there’s a lot going on!

On September 25 we’re hosting a workshop on Copyright and Fair Use in Digital Projects. With pretty much everyone being a digital creator these days, the training will help you navigate copyright, fair use, and other rights related to including third-party content in your digital project. We’ll also provide an overview of what your intellectual property rights are as a creator and ways to license and share your own work too.

We’re happy to again present a series of publishing workshops to guide graduate students and postdocs on a variety of copyright, publishing, and scholarly impact issues. On October 22 we’ll be talking about copyright questions and legal considerations for your dissertation or thesis. October 23 we’re hosting a panel discussion on how to navigate the publication process from dissertation to first book. The event will include discussion from a university press acquisitions editor, a first-time book author, and an author rights expert. And October 25 we’re wrapping up the week with a workshop that will provide participants with practical strategies and tips for promoting your scholarship, increasing citations, and understanding scholarly reach and metrics.

There are lots of ways the Office of Scholarly Communication Services is here to help faculty, students, and staff. A quick rundown:

- Check out our website which has helpful information on a variety of topics, including copyright and fair use, the scholarly publishing lifecycle and sharing research data, UC’s Open Access Policy and OA funding opportunities, and much more.

- Interested in creating an open digital textbook? Take a look at UC Berkeley’s Open Book Publishing platform (anyone with a Berkeley email can signup for a free account), and get in touch with us about our Open Educational Resources (OER) grant program.

- Keep an eye on our events calendar for more workshops and trainings.

- Follow our blog and social media.

Want help or more information? Send us an email. We can provide individualized support and personal consultations, in-class and online instruction, presentations and workshops for small or large groups & classes, and customized support and training for departments and disciplines.