Tag: BL Latin America

In times of Corona: Celebrating African American History Month and Latin America

As we celebrate African American History Month in the United States, America’s racialized past cannot be ignored nor forgotten. Latin America also has a large population of Afro-Latinos and this post is dedicated to providing our readers with some of the highlights from UC Berkeley Library’s collections from Latin America that deal with the nuanced history of Africans in Latin America. We have chosen only a few public domains and open access books that can be read online in times of ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Also, there are some books that are not in the public domain but can be read online by authenticating oneself using the UC Berkeley credentials.

We leave you with a clip about Argentina también es afro: Las conquistas de la libertad (capítulo completo) – Canal Encuentro

Spanish (Europe)

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

If you walk down the street in many parts of the world and ask a stranger who fought the windmills, they would most probably answer Don Quixote. But they would not necessarily know the name of its author, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1547-1616). This not-so-prolific dramaturge, poet and novelist has nonetheless had a major impact on the development of Western literature, influencing his English contemporary William Shakespeare, 19th-century French author Gustave Flaubert, and 20th-century Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges, just to name a few.

Cervantes did not come to prominence until much later in his life. His experiences as a soldier, a captive and a witness to the struggles of the Spanish empire shaped his distinctive oeuvre: a literary world of experimentation, as can be seen in his Exemplary Novels (1613), a world in which possibilities of reconciliation between conflictive individuals, ideals and desires remained hollow, inconclusive and, in many cases, without avail. Among other factors, what distinguishes Cervantes’ literary production is its unclassifiable nature, making it hard to try and fit the works in their presumed corresponding genre. One good example is his posthumous work The Travails of Persiles and Sigismunda (1616), where the Byzantine novel is mutilated to such an extent that, at points, it becomes almost unrecognizable.

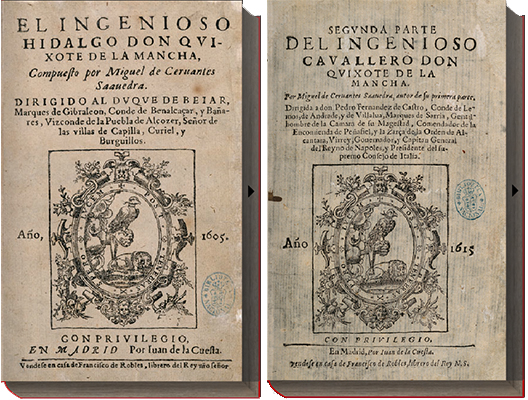

Yet this unfittedness is most evident in Don Quixote (Part I published in 1605; Part II in 1615). The confusion between reality and fiction, the untrustworthiness of the multiple narrators, the intentional errors and misnomers, the three-dimensionalism of Don Quixote’s squire, Sancho, who has a love-hate relationship with his master, the utter destruction of the chivalric world, and the encounter with oppressed minorities are but some of the factors that have undoubtedly contributed to the sustained appeal of Don Quixote. The protagonist, an old man who “loses his mind” reading novels of chivalry, was, in Western literature, a pioneering self-proclaimed “hero.” He offers and imposes his help unto people who rarely take him seriously. Moreover, he only becomes popular, within his diegetic world, when in Part II he is defined by others as a caricature. This caricature remains dominant in the collective imaginary of readers, as can be seen, for example, in Picasso’s well-known depiction of the character.

Although most masterpieces ultimately attempt to challenge a comfortable experience of reading where we readily identify with fictitious characters; Don Quixote still manages to attract the empathy of its readers who may or may not closely identify with the knight-errant. Don Quixote is beaten up, both physically and metaphorically, yet his innocent, albeit selfish at times, intentions have ultimately won the hearts of a diverse audience over the centuries.

Today, the Spanish language, or Castilian as it is referred to in Europe, has grown from around 14 million speakers at the time of Cervantes to 477 million native speakers worldwide. It is now the second most used language for international communication and the most studied languages on the planet.[1] At Berkeley, Spanish is one of the most widely used languages for scholarship after English, particularly in departments such as Anthropology, Comparative Literature, Ethnic Studies, Film & Media, Gender & Women’s Studies, History, Linguistics, Political Science, and Rhetoric. Interdisciplinary graduate programs in Latin American Studies, Medieval Studies, Romance Languages and Literature, and Medieval and Early Modern Studies also require reading of original texts in Spanish.

Nasser Meerkhan, Assistant Professor

Department of Near Eastern Studies & Department of Spanish & Portuguese

Source consulted:

- Elias, D. José Antonio. Atlas historico, geográfico y estadístico de España y sus posesiones de ultramar. Barcelona : Imprenta Hispana, 1848; Hernández Sánchez Barbara, Mario. “La población hispanoamericana y su distribución social en el siglo XVIII,” Revista de estudios políticos, no.78 (1954); López, Morales H, and El español: una lengua viva. Informe 2017. Madrid : Arco Libros, S.L. : El Instituto, 2017.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha

Author: Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de, 1547-1616.

Imprint: En Madrid : por Iuan de la Cuesta, 1605, 1615.

Edition: 1st

Language: Spanish (Europe)

Language Family: Indo-European

Source: Biblioteca Nacional de España

URL: http://quijote.bne.es/libro.html (requires Flash)

Other online editions:

- El ingenioso hidalgo don Quixote de la Mancha / compuesto por Miguel de Ceruantes Saauedra. En Madrid : por Iuan de la Cuesta, 1605.

- Segunda parte del ingenioso cauallero don Quixote de la Mancha / por Miguel de Ceruantes Saauedra, autor de su primera parte. En Madrid : por Iuan de la Cuesta, 1615.

- The History of Don Quixote. Translated into English by J.W. Clark. Illustrated by Gustave Doré. New York, P.F. Collier, 1871 .

Select print editions at Berkeley:

Considered to be the most translated work every written, the Library has editions in French, German, Hebrew, Armenian, Quechua, and more. The earliest and best illustrated editions reside in The Bancroft Library.

- El ingenioso hidalgo don Quixote de la Mancha. Burgaillos. Published Impresso con licencia, en Valencia : En casa de Pedro Patricio Mey : A costa de Iusepe Ferrer mercader de libros, delante la Diputacion, 1605.

- Segunda parte del ingenioso cauallero don Quixote de la Mancha. En Valencia : En casa de Pedro Patricio Mey, junto a San Martin : A costa de Roque Sonzonio mercader de libros, 1616.

- Vida y hechos del ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha. Nueva edicion, corregida y ilustrada con 32 differentes estampas muy donosas, y apropriadas à la materia. Amberes, Por Henrico y Cornelio Verdussen, 1719.

- El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha / por Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra ; obra adornada de 125 estampas litográficas y publicada por Masse y Decaen, impresore litógrafos y editores, callejon de Santa Clara no 8. México : Impreso por Ignacio Cumplido, calle de los Rebeldes num. 2, 1842.

- Don Quixote / Miguel de Cervantes ; a new translation by Edith Grossman ; introduction by Harold Bloom. New York : Ecco, c2003.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Nahuatl

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

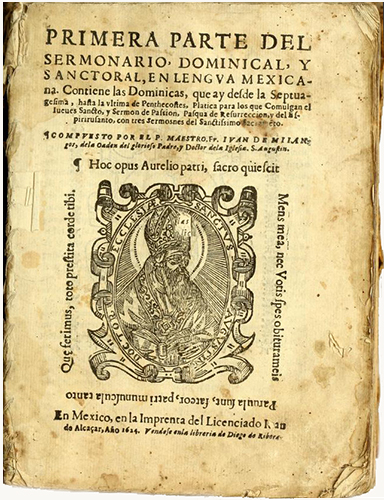

Written in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, the Primera parte del sermonario, dominical, y sanctoral, en lengua mexicana was published in Mexico City in 1624 at Juan de Alcázar’s printing press. The title of this collection of sermons is representative of the early colonial printing in Mexico City as well as the Augustinian order’s testament to the proselytizing efforts of the Catholic Church in Mexico. Only the first part of this Nahuatl text was ever published. Its author, Fr. Juan de Mijangos, is also well known for his Espejo Divino (1607).

As noted by Hortensia Calvo, director of the Latin American Library at Tulane University, Spain’s ideological, political and administrative control was possible with the early colonial press: “The first presses were brought to Mexico City and Lima for the explicit purpose of aiding missionaries in the Christianization of the native population.”[1] However, in the 17th century, following the Conquest, the Spanish occupiers dealt with many different populations of the region, hence many books were printed in the indigenous languages and, most importantly, not all texts were created for colonial or religious purposes. James Lockhart shows that, as early as 1545, the Nahuas of central Mexico adopted the Latin alphabet for their own purposes, beyond the interests of the colonial authorities and missionaries.[2] Indeed, former Berkeley professor José Rabasa argues that the “Alphabetical writing does not belong to rulers; it also circulates in the mode of a savage literacy. Bearing no trace of Spanish intervention in its production, the Historia de Tlatelolco exemplifies a form of grassroots literacy in which indigenous writers operated outside the circuits controlled by missionaries, encomenderos, Indian judges and governors, or lay officers of the crown.”[3] Several such texts have been digitized by the French National Library, including the Diario de Don Domingo de San Anton Muñón Chimalpáhin Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin (1579-1660).

Nevertheless, Marina Garone Gravier notes “there was a lack of in-depth knowledge of Nahuatl by some who composed these early sermons related books.”[4] Since the foundation of the Aztec Empire in 1325, Nahuatl played an essential role in daily workings. Published 103 years after the fall of the Aztec in 1521, the sermon book featured here evinces the continuation of Nahuatl during the early days of the Spanish Empire. Frances Kartunnen points out: “At the time of Spanish Conquest of Mexico [Nahuatl] was the dominant language of Mesoamerica, and Spanish friars immediately set about learning it. Some of them made heroic efforts to preach in Nahuatl and to hear confession in the language. To aid in these endeavors, they devised an orthography based on Spanish conventions and composed Nahuatl language breviaries, confessional guides, and collection of sermons, which were among the first books printed in the New World. Nahuatl speakers were taught to read and write their language, and under Friars’ direction the surviving guardians of an oral tradition set down in writing particulars of their shattered culture in the Florentine Codex and other ethnographic collections of Fray Bernardino de Sahagún and his contemporaries.”[5]

Today there are over one million Nahuatl speakers in Mexico and in the diasporic communities in the United States.[6] Yet, there are several dozens of Nahuatl dialects and, since this non-Romance language adopted the Latin Alphabet, it is difficult to apply standard orthographic principles to all of them.[7] Nonetheless, the following are essential textbooks for the teaching and learning of standardized Nahuatl: Richard Andrew’s Introduction to Classical Nahuatl, James Lockhart’s Nahuatl as Written, Michel Launey’s An Introduction to Classical Nahuatl and, for more advanced students, James Lockhart’s edition of Horacio Carochi’s Grammar of the Mexican Language.[8] Many other resources are available in print and digital format; for example, the University of Oregon’s online Nahuatl Dictionary, Molina’s bilingual dictionary Vocabulario en lengua castellana y mexicana (1571), UNAM’s online Gran Diccionario Náhuatl, and the app Vamos a aprender náhuatl.

Nahuatl language courses are available through UCLA’s distance learning program[9] and University of Utah’s Intensive Nahuatl Language and Culture Summer Program in Salt Lake City. The latter program, previously sponsored at Yale, has prepared many contemporary US-based Nahuatl scholars.[10] At UC Berkeley, the Joseph A. Myers Center for Research on Native American Issues has offered annual Nahuatl workshops,[11] and The Bancroft Library holds over 460 items, including the Primera parte del sermonario, dominical, y sanctoral, en lengua mexicana, concerning the Nahuatl language in its renowned Latin Americana Collection.[12]

The librarian for the Caribbean and Latin American Studies has requested this post to be published on September 16, 2019, which is is celebrated as the day of Independence in Mexico.

Contribution by Lilahdar Pendse

Librarian for Latin American Studies, Doe Library

Carlos Macías Prieto

PhD student, Department of Spanish & Portuguese

Sources consulted:

- Calvo, Hortensia. “The Politics of Print: The Historiography of the Book in Early Spanish America.” Book History, vol. 6, 2003, pp. 277–305. JSTOR.

- Lockhart, James. The Nahuas After the Conquest: A Social and Cultural History of the Indians of Central Mexico, Sixteenth Through Eighteenth Centuries. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996.

- Rabasa, José. Writing Violence on the Northern Frontier: The Historiography of Sixteenth-Century New Mexico and the Legacy of Conquest. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2000.

- Gravier, Marina Garone. “La tipografía y las lenguas indígenas: estrategias editoriales en la Nueva España.” La Bibliofilía, vol. 113, no. 3, 2011, pp. 355–374. JSTOR.

- Karttunen, Frances. An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl. Norman: Univ. of Oklahoma Press, 1992.

- Janick, Jules, and Arthur O. Tucker. Unraveling the Voynich Codex. Cham Springer , 2018.

- Andrews, J R. Introduction to Classical Nahuatl. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2003.

- Introduction to Nahuatl, Center for Latin American Studies, Stanford (accessed 9/12/19)

- Distance Learning Language Classes, UCLA (accessed 9/12/19)

- Beginners and Advanced Nahuatl Language and Culture Workshops, UCB (accessed 9/12/19)

- Utah Nahuatl Language and Culture Program (accessed 6/18/19)

- Latin Americana: Mexico and Central America, The Bancroft Library, UCB (accessed 9/12/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Primera parte del sermonario, dominical, y sanctoral, en lengua mexicana : contiene las Dominicas, que ay desde la Septuagesima, hasta la vltima de Penthecostes, platica para los que comulgan el iueues sancto, y Sermon de Passion, pasqua de Resurreccion, y del Espiritusanto, con tres sermosnes [sic] del sanctissimo sacrame[n]to / compuesto por el P. maestro Fr. Iuan de Miiangos, de la Oaden [sic] del glorioso Padre, y Doctor dela Iglesia. S. Augustin. (1624).

Author: Mijangos, Juan de, d. ca. 1625

Imprint: En Mexico : En la imprenta del licenciado Iuan de Alcaçar : Vendese en la libreria de Diego de Ribera : año 1624.

Edition: 1st

Language: Nahuatl

Language Family: Uto-Aztecan

Source: The Internet Archive (John Carter Brown Library)

URL: https://archive.org/details/primerapartedels00mija

Other Nahuatl texts online:

- Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin (1579-1660). Diario de Don Domingo de San Anton Muñón Chimalpáhin, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- Fray Bernardino de Sahagún (1499–1590). Historia general de las cosas de nueva España (The Florentine Codex). World Digital Library (Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana).

- Gran Diccionario Náhuatl [online]. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México [Ciudad Universitaria, México D.F.]: 2012.

- Molina, Alonso de, d. 1585. Vocabulario en lengua Castellana y Mexicana. En Mexico : en casa de Antonio de Spinosa, 1571.

- Online Nahuatl Dictionary (University of Oregon)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- The Bancroft Library has in its collection one of eight surviving copies of Primera parte del sermonario, dominical, y sanctoral, en lengua mexicana (1624) held in U.S. libraries.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Portuguese (Brazil)

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

“A imaginação foi a companheira de toda a minha existência, viva, rápida, inquieta, alguma vez tímida e amiga de empacar, as mais delas capaz de engolir campanhas e campanhas, correndo.”

“Imagination has been the companion of my whole existence — lively, swift, restless, at times timid and balky, most often ready to devour plain upon plain in its course.” (trans. Helen Caldwell p. 41, Dom Casmurro)

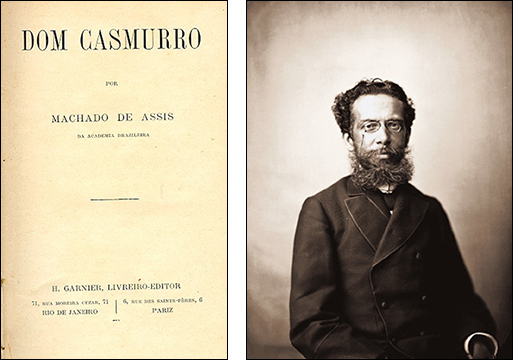

The novel Dom Casmurro is considered a masterpiece of literary realism and one of the most significant works of fiction in all of Latin American literature. The late Brazilian literary critic Afrânio Coutinho called it possibly one of the best works written in the Portuguese language, and it has been required reading in Brazilian schools for more than a century.[1] At UC Berkeley, generations of students in literature courses have been enjoying the rich complexity of this work of prose since the 1950s when the author began receiving recognition worldwide. Indelibly influenced by French social realists such as Honoré de Balzac, Gustave Flaubert and Émile Zola, Dom Casmurro is a sardonic social critique of Rio de Janeiro’s bourgeoisie. The satirical novel takes the reader on a terrifying journey into a mind haunted by jealousy via an unreliable first-person narrative told by Bento Santiago (Bentinho) who suspects his wife Capitú of adultery.

Dom Casmurro was written by multiracial and multilingual Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis (1864-1908) who was an essayist, literary critic, reporter, translator, government bureaucrat. He was most venerated for his short stories, plays, novellas, and novels which were all set in his milieu of Rio de Janeiro. The son of a freed slave who had become a housepainter and a Portuguese mother from the Azores, he grew up in an affluent household under a generous patroness where his parents were agregados (domestic servants).[2] A prodigy of sorts, he began writing at an early age, and quickly ascended the socio-cultural ladder in a country that did not abolish slavery until 1888 with the Lei Áurea (Golden Act).[3] At the center of a group of well-known poets and writers, Machado founded the Academia Brasileira de Letras (Brazilian Academy of Letters) in 1896, became its first president, and was perpetually reelected until his death in 1908.[4] “Even more remarkable than Machado’s absence from world literature,” wrote Susan Sontag, “is that he has been very little known and read in Latin America outside Brazil — as if it were still hard to digest the fact that the greatest author ever produced in Latin America wrote in the Portuguese, rather than the Spanish, language.”[5]

With a population of over 210 million, Brazil has eclipsed Portugal and its former colonies in Africa and Asia and now constitutes more than 80 percent of the world’s Portuguese speakers. Portuguese is the sixth most natively spoken language globally.[6] While European Portuguese (EP) is considered a less commonly taught language in American universities, this is not the case for Brazilian Portuguese (BP) where it has become increasingly popular. The Modern Language Association’s recently released study on languages taught in U.S. institutions, ranked Portuguese as the eleventh most taught language.[7] BP and EP are the same language but have been evolving independently, much like American and British English, since the 17th century. Today, the linguistic variations (phonetics, phonology, syntax, morphology, semantics, pragmatics) are so stark that a non-fluent observer might mistake the two for entirely different languages. In 1990, all Portuguese-language countries signed the Acordo Ortográfico da Língua Portuguesa — a treaty to standardize spelling rules across the Lusophone world — which went into effect in Brazil in 2009 and in Portugal in 2016.[8]

At Berkeley, Brazilian literature is offered for all periods and levels of study through the Department of Spanish and Portuguese’s Luso-Brazilian Program directed by Professor Candace Slater.[9] Her research centers on traditional narrative and cordel ballads, and she was awarded the Ordem de Rio Branco in 1996 — the highest honor the Brazilian government accords a foreigner — and in 2002, the Ordem de Merito Cultural. Other Brazilianists in the department include professors Natalia Brizuela and Nathaniel Wolfson. Graduate students with an interest in Brazil who are part of the Hispanic Language and Literatures (HLL), Romance Language and Literatures (RLL), and Latin American Studies programs delve into all aspects of the nation’s history, culture, and language.[10]

Contribution by Claude Potts

Librarian for Romance Language Collections, Doe Library

Sources consulted

- Coutinho Afrânio. Machado de Assis na literatura brasileira. Academia Brasileira de Letras, 1990.

- “More on Machado,” Brown University Library’s Brasiliana Collection. (accessed 7/19/19)

- Rodriguez, Junius P. Encyclopedia of Emancipation and Abolition in the Transatlantic World. Armonk, NY: Sharpe Reference, 2007.

- Preface to Dom Casmurro: A Novel by Machado de Assis. Translated by Helen Caldwell. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966, c1953.

- Sontag, Susan. “Afterlives: the Case of Machado de Assis,” New Yorker (April 29, 1990).

- CIA World Factbook (accessed 7/19/19)

- Modern Language Association of America. Enrollments in Languages Other Than English in United States Institutions of Higher Education, Summer 2016 and Fall 2016: Final Report (June 2019). (accessed 7/19/19)

- Vocabulário Ortográfico da língua portuguesa. 5a ed. São Paulo, SP : Global Editora ; Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil : Academia Brasileira de Letras, 2009; and Academia das Ciências de Lisboa. Vocabulário ortográfico atualizado da língua portuguesa. Lisboa : Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda, 2012.

- Portuguese (PORTUG) – Berkeley Academic Guide (accessed 7/26/19)

- Hispanic Languages & Literatures, Romance Languages and Literatures, Latin American Studies, UC Berkeley (accessed 7/25/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Dom Casmurro

Title in English: Dom Casmurro : novel

Author: Machado de Assis, Joaquim Maria, 1839-1908.

Imprint: Rio de Janeiro; Paris: Garnier, 1899.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Portuguese

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil

URL: http://acervo.bndigital.bn.br/sophia/index.asp?codigo_sophia=4883

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- O romance Dom Casmurro de Machado de Assis / Maximiano de Carvalho e Silva. Niterói : Editora da UFF, 2014. Includes the reproduction of the 1899 edition.

- Dom Casmurro. Ilustrações, Carlos Issa ; posfácio, Hélio Guimarães. São Paulo, SP : Carambaia, 2016.

- Dom Casmurro : A Novel. Translated from the Portuguese by John Gledson ; with a foreword by John Gledson and an afterword by João Adolfo Hansen. Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Dom Casmurro: A Novel by Machado de Assis. Translated by Helen Caldwell. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966, c1953.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Spanish (Latin America)

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

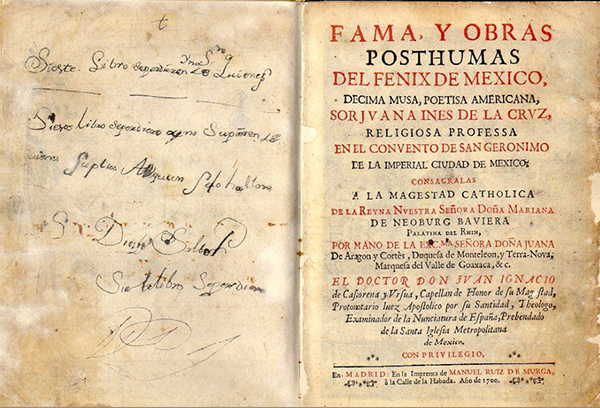

Nun, rebel, genius, poet, persecuted intellectual, and proto-feminist, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (Nepantla 1648-Mexico City 1695) was the most distinguished intellectual in the pre-Independence American colonies of Spain. She was called “Tenth Muse” in her own time and continues to inspire the popular and scholarly imagination. Generations of Mexican schoolchildren have memorized her satirical ballad “Hombres necios que acusáis / a la mujer sin razón… “ (You foolish men who cast all blame on women), and her portrait appears on the 200-peso note. Despite her status as an icon of Mexican culture, an annotated edition of her complete works was not published until the tercentenary of her birth in the mid-1950s, and the complexity of her poetry, prose, and theater was known only by reputation until the second wave of feminism brought scholarly attention to her work in the 1970s. Octavio Paz’s monumental study, Sor Juana, o, Las trampas de la fe (Sor Juana, or The Traps of Faith) appeared in 1982.

An intellectual prodigy brought to the viceregal court of New Spain in her teens, Sor Juana was largely self-taught. In 1669, she entered the convent of San Jerónimo in order to continue her studies. Although women were excluded from the study of theology and rhetoric, she wrote a brilliant critique of a renowned Portuguese cleric’s sermon, and was reprimanded by the Bishop of Puebla, who wrote under a female pseudonym. Sor Juana’s “Respuesta a sor Filotea” (1691, “Reply to Sister Philothea”) displayed her erudition in defense of her intellectual passion, arguing that St. Paul’s often-quoted admonition that women should keep silent in church (mulieres in ecclesia taceant), should not prohibit women’s pursuit of knowledge and instruction of young girls. Other significant works include secular and religious theater; philosophical poetry; passionate poems to the noblewomen who were her patrons; and villancicos, sets of songs she was commissioned to write for religious celebrations.

Sor Juana’s long epistemological poem, Primero sueño (First Dream) epitomizes the Creole appropriation of the Baroque and yet she weaves into her poetry and theater a recognition of the humanity of indigenous peoples. While her literary models were European and her poetry was first published in Spain, her works evince an American consciousness in the representation of the violence of the conquest in the loa to El divino Narciso (Divine Narcissus) and her use of Nahuatl in the villancicos.

Contribution by Emilie Bergmann

Professor, Department of Spanish & Portuguese

Title: Fama, y obras póstumas

Title in English: Homage and posthumous works

Author: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1648-1695)

Imprint: Madrid: Manuel Ruiz de Murga, 1700.

Edition: 1st

Language: Spanish (Latin America)

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Universitätsbibliothek, Universität Bielefeld

URL: http://ds.ub.uni-bielefeld.de/viewer/image/1592397/1

Other online editions:

- Inundación castálida, de la única poetisa, musa décima, soror Juana Inés de la Cruz … (Madrid: Juan García Infanzón, 1689) and the first edition of Segundo volumen de las obras de soror Juana Inés de la Cruz (Sevilla: Tomás López de Haro, 1692).

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Critical and annotated editions of the first two volumes of Sor Juana’s work, Inundación Castálida (1689) and Segundo tomo (1693), as well as Fama, y obras póstumas and editions of complete and selected works are available in printed form in The Bancroft Library and the Main Stacks.

- Sor Juana’s complete works were published in four volumes: Obras completas, Alfonso Méndez Plancarte and Alberto G. Salcedo. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1951-57. Many English translations of selected works of Sor Juana’s works are also in OskiCat including those of Alan S. Trueblood, Margaret Sayers Peden, Amanda Powell, and Edith Grossman.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)