Tag: “BL Africa”

Amharic

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

With over 2,000 vernacular languages, sub-Saharan Africa includes approximately one-third of the world’s languages.[1] Many of these will likely disappear in the next hundred years, displaced by dominant regional languages like Amharic.

Amharic, alternately known as Abyssinian, Amarigna, Amarinya, Amhara, or, simply, Ethiopian, is a Semitic language spoken by over 25 million people. It is part of the Semitic branch of the Afroasiatic language group, which spans, as the name suggests, two continents, primarily West Asia as well as North Africa and the Horn of Africa. In the 13th century, it evolved as a spoken language and replaced Ge’ez as the common means of communication in the imperial court where it was referred to as the language of the king.[2] Today, Amharic is spoken as the first language (L1) by the Amhara of the northwest Highlands of Ethiopia. As the official language of Ethiopia, it has become the lingua franca of the country.[3]

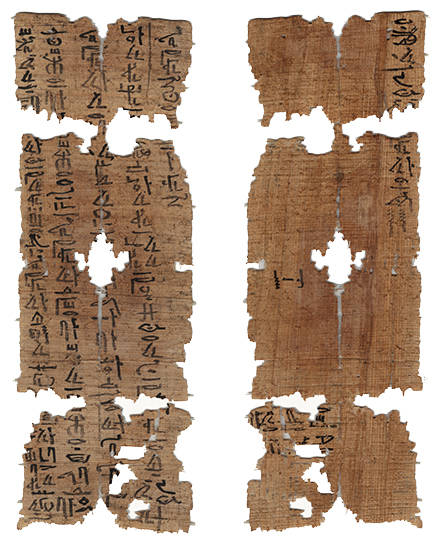

Beyond Amharic’s inherent importance in the realm of politics, education, and business as a result of its privileged status as the official language of Ethiopia, it is also a major literary language in the country. Early (pre-20th century) Ethiopian literature often took on religious themes and was published in the ancient Semitic language of Ge‘ez. However, by the turn of the 20th century, literary publications in Amharic became more common, signaling the language’s ascent. The featured text here, Ethiopian Literature (in Amharic): Chrestomathy, a collection of seventeen samples of Ethiopian literature by various authors, captures the expansion of Amharic influence in literary publications. The collection covers one-hundred years of Ethiopian literary prose beginning with “Story Born at Heart” by Afewerk Ghebre Jesus, originally published in 1908, up to the early 2000s with a piece by one of the great modern Ethiopian writers, Adam Reta. The collection, generously adorned with illustrations throughout, was designed for students of Amharic philology.

At UC Berkeley, based on research interest and student demand, especially from heritage students, with Title VI funding through the Center for African Studies, Amharic language study (at the elementary and intermediate levels) has been offered since the fall of 2019. Students enrolled in Amharic are among the few in the whole of the United States formally studying the language and are at the vanguard in recognizing Africa’s increasing importance demographically, socially, and culturally.[4]

Contribution by Adam Clemons

Librarian for African and African American Studies, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Moseley, Christopher, and Alexandre Nicolas. Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. Paris: UNESCO, 2010.

- Meyer, Ronny. “Amharic as Lingua Franca in Ethiopia.” Lissan: Journal of African Languages and Linguistics. 20 1/2 (2006).

- Ethnologue: Languages of the World (accessed 5/16/20)

- Saavedra, Martha and Leonardo Arriola. “UC Berkeley Needs to Support African Language Programs” Daily Californian (February 22, 2019) (accessed 5/16/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Ethiopian Literature (in Amharic): Chrestomathy

Author: Galina (Galina Aleksandrovna) Balashova, compiler.

Imprint: Lac-Beaport, Quebec : MEABOOKS Inc., 2016. (Baltimore, Md. : Project MUSE, 2015.)

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Amharic

Language Family: Afro-Asiatic, South Semitic

Source: Project Muse

URL: https://muse-jhu-edu.libproxy.berkeley.edu/book/48900 (UCB access only)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Ethiopian literature (in Amharic): Chrestomathy / G.A. Balashova, comp. Lac-Beauport, Quebec: MeaBooks Inc, 2016.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Chichewa

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

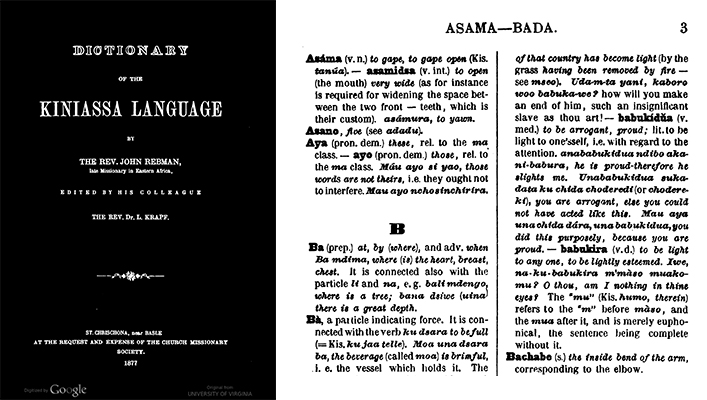

“My study of the Kiniassa was to me such a continual intellectual feast, that days and weeks fled so quickly as I never remembered they had done before, and it was with great reluctance that I tore myself from it when we had to get ready for our voyage to Aden.”

— Reverend John Rebman

With over 2,000 vernacular languages, sub-Saharan Africa includes approximately one-third of the world’s languages.[1] Many of these will likely disappear in the next hundred years, displaced by dominant regional languages like Chichewa. Also known as Chinyanja or Kiniassa, Chichewa is spoken in west-central and southwest Africa. In total, the language claims nearly 10 million speakers across the region. It is an official language — along with English — in Malawi and is officially recognized in Zambia and Mozambique where it is known as Nyanja. Chichewa is part of the Bantu branch of the larger Niger-Congo phylum. Linguistics and archaeologists suggest that these languages began in the grasslands of northwestern Cameroon and north-eastern Nigeria over two thousand years ago and spread across central and southern Africa through a combination of migration and conquest.[2]

The Dictionary of the Kiniassa Language, compiled by the reverend Johannes Rebmann brom 1853-54 and posthumously published in 1877, was the first extensive written record of the Chichewa language. It is representative of the fairly prolific publishing output of European missionaries — principally religious (bible translations, hymn books, etc.) or grammar and vocabulary texts — during the early colonial period.

These types of texts — especially the grammar and vocabulary texts — can offer a unique vantage point from which to view the imaginative nature of work that is otherwise often viewed as static. For example, in works of comparative religion, scholars can use these creative texts to gain insight into how missionaries grappled with words to accurately define religious concepts such as “sin” to serve their proselytizing purposes. Ultimately, old words were re-defined or altogether new words were crafted to meet the present need.

Contribution by Adam Clemons

Librarian for African and African American Studies, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Moseley, Christopher, and Alexandre Nicolas. Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. Paris: UNESCO, 2010.

- Dalby, Andrew. Dictionary of Languages: The Definitive Reference to More Than 400 Languages. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Dictionary of the Kiniassa Language

Author: Rebman, John, 1820-1876.

Imprint: St. Chrischona: Church Missionary Society, 1877.

Edition: 1st

Language: Chichewa

Language Family: Niger-Congo

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Virginia)

URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uva.x000079094

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Dictionary of the Kiniassa language, by the Rev. John Rebman, edited by his colleague, the Rev. Dr. L. Krapf. St. Chrischona, near Basle, Switzerland, The Church missionary society, 1877.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Portuguese (Brazil)

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

“A imaginação foi a companheira de toda a minha existência, viva, rápida, inquieta, alguma vez tímida e amiga de empacar, as mais delas capaz de engolir campanhas e campanhas, correndo.”

“Imagination has been the companion of my whole existence — lively, swift, restless, at times timid and balky, most often ready to devour plain upon plain in its course.” (trans. Helen Caldwell p. 41, Dom Casmurro)

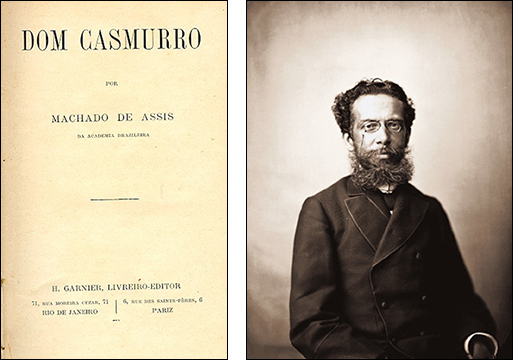

The novel Dom Casmurro is considered a masterpiece of literary realism and one of the most significant works of fiction in all of Latin American literature. The late Brazilian literary critic Afrânio Coutinho called it possibly one of the best works written in the Portuguese language, and it has been required reading in Brazilian schools for more than a century.[1] At UC Berkeley, generations of students in literature courses have been enjoying the rich complexity of this work of prose since the 1950s when the author began receiving recognition worldwide. Indelibly influenced by French social realists such as Honoré de Balzac, Gustave Flaubert and Émile Zola, Dom Casmurro is a sardonic social critique of Rio de Janeiro’s bourgeoisie. The satirical novel takes the reader on a terrifying journey into a mind haunted by jealousy via an unreliable first-person narrative told by Bento Santiago (Bentinho) who suspects his wife Capitú of adultery.

Dom Casmurro was written by multiracial and multilingual Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis (1864-1908) who was an essayist, literary critic, reporter, translator, government bureaucrat. He was most venerated for his short stories, plays, novellas, and novels which were all set in his milieu of Rio de Janeiro. The son of a freed slave who had become a housepainter and a Portuguese mother from the Azores, he grew up in an affluent household under a generous patroness where his parents were agregados (domestic servants).[2] A prodigy of sorts, he began writing at an early age, and quickly ascended the socio-cultural ladder in a country that did not abolish slavery until 1888 with the Lei Áurea (Golden Act).[3] At the center of a group of well-known poets and writers, Machado founded the Academia Brasileira de Letras (Brazilian Academy of Letters) in 1896, became its first president, and was perpetually reelected until his death in 1908.[4] “Even more remarkable than Machado’s absence from world literature,” wrote Susan Sontag, “is that he has been very little known and read in Latin America outside Brazil — as if it were still hard to digest the fact that the greatest author ever produced in Latin America wrote in the Portuguese, rather than the Spanish, language.”[5]

With a population of over 210 million, Brazil has eclipsed Portugal and its former colonies in Africa and Asia and now constitutes more than 80 percent of the world’s Portuguese speakers. Portuguese is the sixth most natively spoken language globally.[6] While European Portuguese (EP) is considered a less commonly taught language in American universities, this is not the case for Brazilian Portuguese (BP) where it has become increasingly popular. The Modern Language Association’s recently released study on languages taught in U.S. institutions, ranked Portuguese as the eleventh most taught language.[7] BP and EP are the same language but have been evolving independently, much like American and British English, since the 17th century. Today, the linguistic variations (phonetics, phonology, syntax, morphology, semantics, pragmatics) are so stark that a non-fluent observer might mistake the two for entirely different languages. In 1990, all Portuguese-language countries signed the Acordo Ortográfico da Língua Portuguesa — a treaty to standardize spelling rules across the Lusophone world — which went into effect in Brazil in 2009 and in Portugal in 2016.[8]

At Berkeley, Brazilian literature is offered for all periods and levels of study through the Department of Spanish and Portuguese’s Luso-Brazilian Program directed by Professor Candace Slater.[9] Her research centers on traditional narrative and cordel ballads, and she was awarded the Ordem de Rio Branco in 1996 — the highest honor the Brazilian government accords a foreigner — and in 2002, the Ordem de Merito Cultural. Other Brazilianists in the department include professors Natalia Brizuela and Nathaniel Wolfson. Graduate students with an interest in Brazil who are part of the Hispanic Language and Literatures (HLL), Romance Language and Literatures (RLL), and Latin American Studies programs delve into all aspects of the nation’s history, culture, and language.[10]

Contribution by Claude Potts

Librarian for Romance Language Collections, Doe Library

Sources consulted

- Coutinho Afrânio. Machado de Assis na literatura brasileira. Academia Brasileira de Letras, 1990.

- “More on Machado,” Brown University Library’s Brasiliana Collection. (accessed 7/19/19)

- Rodriguez, Junius P. Encyclopedia of Emancipation and Abolition in the Transatlantic World. Armonk, NY: Sharpe Reference, 2007.

- Preface to Dom Casmurro: A Novel by Machado de Assis. Translated by Helen Caldwell. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966, c1953.

- Sontag, Susan. “Afterlives: the Case of Machado de Assis,” New Yorker (April 29, 1990).

- CIA World Factbook (accessed 7/19/19)

- Modern Language Association of America. Enrollments in Languages Other Than English in United States Institutions of Higher Education, Summer 2016 and Fall 2016: Final Report (June 2019). (accessed 7/19/19)

- Vocabulário Ortográfico da língua portuguesa. 5a ed. São Paulo, SP : Global Editora ; Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil : Academia Brasileira de Letras, 2009; and Academia das Ciências de Lisboa. Vocabulário ortográfico atualizado da língua portuguesa. Lisboa : Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda, 2012.

- Portuguese (PORTUG) – Berkeley Academic Guide (accessed 7/26/19)

- Hispanic Languages & Literatures, Romance Languages and Literatures, Latin American Studies, UC Berkeley (accessed 7/25/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Dom Casmurro

Title in English: Dom Casmurro : novel

Author: Machado de Assis, Joaquim Maria, 1839-1908.

Imprint: Rio de Janeiro; Paris: Garnier, 1899.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Portuguese

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil

URL: http://acervo.bndigital.bn.br/sophia/index.asp?codigo_sophia=4883

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- O romance Dom Casmurro de Machado de Assis / Maximiano de Carvalho e Silva. Niterói : Editora da UFF, 2014. Includes the reproduction of the 1899 edition.

- Dom Casmurro. Ilustrações, Carlos Issa ; posfácio, Hélio Guimarães. São Paulo, SP : Carambaia, 2016.

- Dom Casmurro : A Novel. Translated from the Portuguese by John Gledson ; with a foreword by John Gledson and an afterword by João Adolfo Hansen. Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Dom Casmurro: A Novel by Machado de Assis. Translated by Helen Caldwell. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966, c1953.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Wolof

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Wolof is the most widely spoken African language in Senegal, predominantly in urban areas. It is also spoken in the West African nations of Mauritania and The Gambia. Within Senegal, approximately 40% of the total population (just over 15 million according to World Bank estimates) are native speakers while the majority of the rest speak it as a second language. In Mauritania, Wolof is spoken by approximately 7% of the total population (estimated at just over 4 million by the World Bank), though the majority of speakers reside in the southernmost part of the country nearest the border with Senegal. About 3% of the total population of The Gambia (estimated at just over 2 million according to the World Bank) speak Wolof but it tends to be disproportionately influential in the country because of its prevalence in Banjul, Gambia’s largest city. Wolof is part of the Senegambia branch of the of the Niger-Congo language family, of which there are some 1,500 other languages.

Démbi Senegaal: ci làmmeñu Wolof is an account of the history of Senegal from antiquity through the end of the 19th century. By retracing these historical events, Paate Sow’s intent is to inform Wolof readers about the unique histories — political, economic, social — of the kingdoms (Jolof, Kajor, Waalao, etc.) that makeup what is today known as Senegal. Though not as culturally significant in the same way as say, Mariama Bâ’s Une si longue lettre, Paate Sow’s Démbi Senegaal: ci làmmeñu Wolof is a rare example of a title published in Wolof and available electronically. Finding titles that met this criteria — published in Wolof while also electronically available — was exceedingly difficult for all African languages represented in this exhibit. Thanks to projects like Céytu, which aims to publish — both in print and electronic form — the major works of literature from the Francophone world in Wolof, finding electronic versions of important works in African languages should be easier.

Wolof was offered for nearly a quarter century to students who could take elementary to advanced-level Wolof under the direction of instructor Alassane Paap Sow. He taught Wolof at UCB for over 20 years, and also developed material in Wolof through the BLC’s Library of Foreign Language Film Clips (LFLFC), a tagged, structured collection of clips from films and searchable database. Additionally, the Center for African Studies pioneered distance learning in the UC system by offering courses in Wolof (as well as Swahili). Wolof has not been offered at UC Berkeley since 2015 due to lack of funding.

Contribution by Adam Clemons

Librarian for African and African American Studies, Doe Library

Title: Démbi Senegaal: ci làmmeñu Wolof

Title in English: n/a

Author: Paate Sow

Imprint: Dakar : Info-edit, 1998.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Wolof

Language Family: Niger-Congo

Source: ALMA Project (African Language Materials Archive Project) of WARC (West African Research Center)

URL: http://www.dlir.org/docs/alma_ebooks/wolof_009.pdf

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Ancient Egyptian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

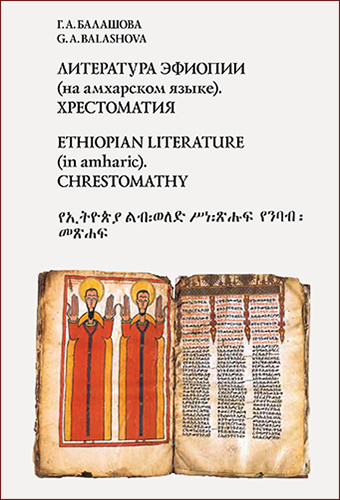

Ancient Egyptian is a language that was spoken in and around the Nile River valley from the 4th millennium BCE through the 11th century CE. The earliest form of this language was written in the Hieroglyphic script. Soon after the development of Hieroglyphs, the availability of papyrus as a light, portable writing material and the complexity of drawing complete Hieroglyphic signs led to the development of Hieratic. This cursive form of the ancient Egyptian script is what an individual named Heni used to write a letter to his deceased father, Meru, sometime between 2160 and 2025 BCE. Heni’s composition is one of a handful of texts known as “Letters to the Dead,” which have been found throughout Egypt written on materials as diverse as pottery, figurines, linen, and stone stelae. Although this genre of text is attested for a period of nearly two thousand years, only a handful of examples survive, all of which share the common goal of communicating a wish or desire from the living to the dead.

The letter of Heni, written in vertical columns, as was typical for Hieratic of this time period, opens with a greeting to Meru before imploring him to intercede on his son’s behalf and offer aid. Heni believes he is being falsely accused of harming someone, insisting the wrong was instigated by other parties. Unfortunately, the details of the event are lacking. These letters are frustratingly vague, as it was assumed that the intended audience — usually a close relative or acquaintance — knew the specifics of the situation. The letter was folded and addressed like letters sent among the living. That is to say, the address was written on the outside (the two short lines written horizontally towards the bottom of the verso of the papyrus): the nobleman (iry-pat), count (haty-a), overseer of priests, Meru. In order to ensure the message was delivered, Heni deposited the small papyrus in his father’s tomb. Whether or not his father (or the living judges) recognized his plea of innocence, we will never know.

Several millennia later, Heni’s papyrus was found during the archaeological excavations of George A. Reisner. Working under the patronage of Phoebe A. Hearst, Reisner excavated the site of Naga ed-Deir between 1901 and 1904. The letter was found in the tomb of Meru (N.3737), which was decorated with images of him enjoying everyday life. The papyrus was shipped by Reisner to Germany for conservation, where it remained until after World War II. When financial difficulties compelled Phoebe Hearst to withdraw funding for the Berkeley Egyptian Excavations in 1905, George A. Reisner was appointed to the faculty at Harvard University and to the curatorial board at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston. A young, enterprising curator at the MFA, William Kelly Simpson, knew of papyri excavated by Reisner and later sought them out in Germany. With Simpson’s help, the papyrus — along with several others — traveled from West Berlin to the MFA. After securing them in Boston, Simpson published the first translation of this text. Despite earlier inquiries from faculty at UC Berkeley, it was not until the 2000s that Professor Donald Mastronarde of the Berkeley Department of Classics ascertained the whereabouts of these papyri and engineered their return to Berkeley. The Letter to the Dead, along with numerous other ancient Egyptian papyri, are now housed in the Center for the Tebtunis Papyri at The Bancroft Library, as part of the Egyptian collections acquired by Phoebe A. Hearst between 1899 and 1905.

Courses in Ancient Egyptian are taught at UC Berkeley in the Department of Near Eastern Studies as part of a program in Egyptology. Students can take classes in several phases of the language, including Old, Middle, and Late Egyptian, and Demotic.

Emily Cole, Postdoctoral Scholar

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, The Bancroft Library

Source consulted:

Simpson, William Kelly. “The Letter to the Dead from the Tomb of Meru (N 3737) at Nag’ Ed-Deir.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, vol. 52, 1966, pp. 39–52. JSTOR.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Letter to the Dead

Author: Heni

Registration Number: Papyrus Hearst 1282

Imprint: 9th or 10th Egyptian Dynasty. First Intermediate Period (Between 2160 and 2025 BCE)

Language: Ancient Egyptian

Language Family: Afro-Asiatic, Semitic

Source: The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, The Bancroft Library (UC Berkeley)

URL: http://dpg.lib.berkeley.edu/webdb/apis/apis2?invno=P%2eHearst%2e1282&sort=Author_Title&item=1

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Swahili

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Swahili, a Bantu language in the Niger-Congo, is the lingua franca of the African Great Lakes region and other parts of eastern and southern Africa. According to the most recent 2015 Ethnologue estimates, there are just over 98 million speakers — 16 million first language speakers; 82 million second language speakers. It is the official language of Tanzania and one of at least two official languages in Kenya, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, and Uganda. Swahili is also listed as an official language of the African Union. Originally, Swahili was written in Arabic script and borrows many words from the language, a result of strong regional ties to the Arab world via trade and religion.

The earliest known Swahili documents were discovered on the Indian Ocean island of Kilwa along the Swahili Coast, which consists of the coastlines and nearby islands of present day Kenya, Tanzania and northern Mozambique. The island of Pemba is also located within the Swahili Coast, which was the home of Kamange and Sarahani, the authors of the poetry found in Kale ya Wahairi wa Pemba: Kamange na Sarahani (The Past of Pemba Poets: Kamange and Sarahani). Kamange and Sarahani were contemporaries and fierce rivals during the latter-half of the 19th century until their deaths in the early 20th century. Both were well regarded along the Swahili Coast. Kamange often took up subjects like love and bravery while Sarahani chose religious topics and moral instruction. Among their influences were the culture and environment of the region. Since both were Muslim, they were also influenced by Islamic literature and the Arabic language, all of which comes out in their writings.

Recognizing the cultural significance of the collection of poetry, Abdurrahman Saggaf Alawy (author of the preface, Shukurani) and Ali Abdala El-Maawy (author, along with Alawy, of the forward, Dibaji) kept the poems safe during the turbulent period during and immediately following the 1964 revolution in Zanzibar. They safely stored the collection for more than 40 years before presenting them to Abdilatif Abdala, editor of this volume, for publication.

Swahili was first offered at UC Berkeley in 1979. Today, elementary through advanced Swahili is offered each semester by Professor David Kyeu. Over the last several years, Swahili enrollment on campus has remained steady with an average of 42 students enrolled each academic term. To support Swahili language use and practice, the Center for African Studies at UC Berkeley hosts a weekly Swahili Language table where Berkeley students as well as members of the larger community can practice and improve their language skills.

Contribution by Adam Clemons

Librarian for African and African American Studies, Doe Library

Title: Kale ya Washairi wa Pemba: Kamange na Sarahani

Title in English: The Past of Pemba Poets: Kamange and Sarahani

Author: Abdilatif Abdalla

Imprint: Oxford: African Books Collective, 2012.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Swahili

Language Family: Niger-Congo

Source: Project Muse

URL: https://muse.jhu.edu/book/22594/

Select print editions in Library:

- Anthology of Swahili poetry = Kusanyiko la mashairi / Ali Ahmed Jahadhmy. Nairobi: Heinemann Educational Books, 1975.

- Dhifa / E. Kezilahabi. Nairobi : Vide-Muwa Publishers, 2008.

- Sauti ya dhiki / Abdilatif Abdalla. Nairobi : Oxford University Press, 1973.

- Taa ya umalenga / tungo za Ahmad Nassir ; zimehairiwa na Abdilatif Abdalla. Nairobi : Kenya Literature Bureau, 1982.

- Taaluma ya ushairi / Kitula King’ei na James Kemoli Amata. Nairobi : Acacia Stantex Publishers, 2001.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)