Tag: photographs

A Californiana Returns to the Bay Area: Ana María de la Guerra de Robinson

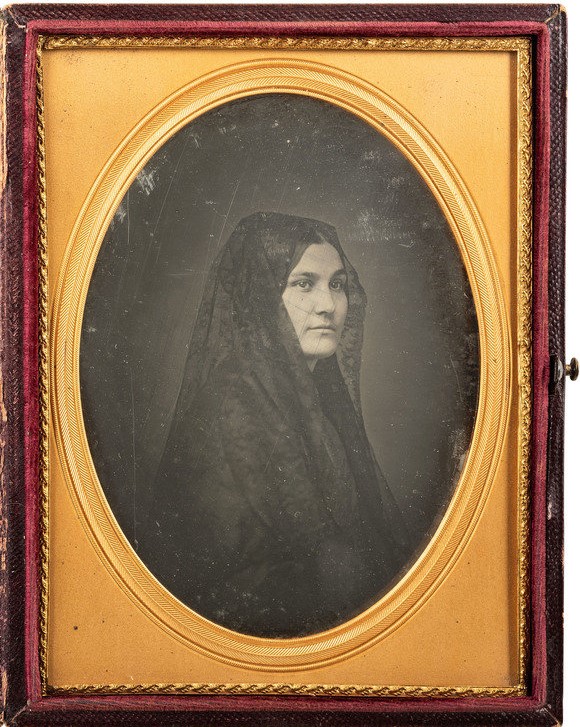

Women’s history month is the perfect time to announce an exciting addition to Bancroft Library’s collection of daguerreotype portraits. At the end of 2023 the library was able to acquire a beautiful 1850s portrait of a Californiana: doña Ana María de la Guerra de Robinson, also known as Anita.

In this large (half plate format) daguerreotype of about 1850-1855, Anita wears a lace mantilla, in the Spanish fashion. A beautiful large daguerreotype like this was an extravagance at the time, and the portrait is all the more evocative because Anita, tragically, died within a few years of its creation.

Fortunately, quite a bit is known about her life. Anita was born into the prominent de la Guerra family of Santa Barbara in 1821 -– the same year the Spanish colonial period ended and control by an independent Mexico began. She was married at age 14, to an American trader and businessman named Alfred Robinson, 14 years her senior. This wedding is described in Richard Henry Dana’s Two Years Before the Mast, so we have an unusually detailed account of what was a grand occasion.

She and her husband snuck away from her family in 1838, leaving their baby daughter behind with her grandparents. Anita, age 15, wrote ”We have left the house like criminals and left here those who have possession of our hearts.” Various writers have interpreted these circumstances differently but, whatever the reason for this strange departure, Anita spent the next 15 years in Boston and the East Coast, seemingly eager to return home, but continually disappointed in the hope. It is hard to imagine that her life was entirely happy, in spite of the steady growth of her family and the prosperity and social prominence the Robinsons and de la Guerras enjoyed.

Having borne seven children, and having witnessed from afar (and apparently mourned) the transition of her homeland from Mexican territory to American statehood, Anita finally returned to California in the summer of 1852. It is likely she had her daguerreotype portrait taken at this time, in San Francisco, although it could have been taken back east. Sadly, she lived just three more years in California, dying in Los Angeles in November 1855, a few weeks after giving birth to a son. She is buried at Mission Santa Barbara.

A study of Anita’s life was published by Michele Brewster in the Southern California Quarterly in 2020 (v.102 no. 2, pg. 101-42) . Read more of her story!

With such a fascinating and relatively well-documented life, we’re thrilled to have Anita’s beautiful portrait here at Bancroft. It joins other de la Guerra family portraits, as well as numerous papers related to the family, including “Documentos para la historia de California” (BANC MSS C-B 59-65) by her father, José de la Guerra y Noriega.

Two of Anita’s sisters had “testimonias” recorded by H.H. Bancroft and his staff; one from Doña Teresa de la Guerra de Hartnell (BANC MSS C-E 67) and another from Angustias de la Guerra de Ord (BANC MSS C-D 134).

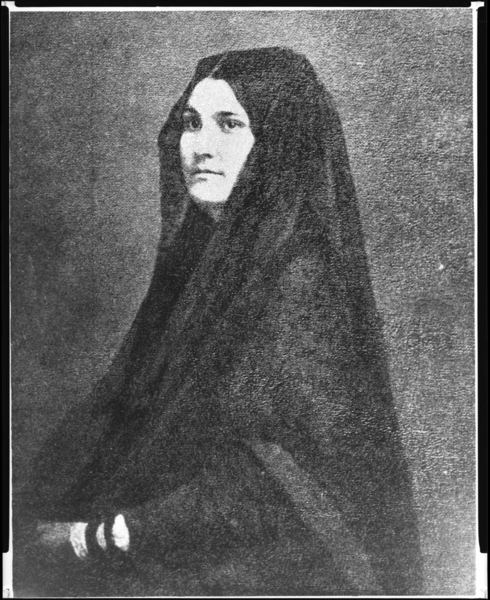

Anita’s daguerreotype itself presents an interesting conundrum and history. The photographer is unknown, as is common with daguerreotypes. The portrait has been known over the years because later copies exist in several historical collections, including the California Historical Society, the Massachusetts Historical Society, and Bancroft Library’s own Portrait File.

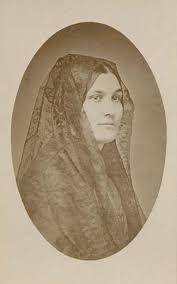

The daguerreotype acquired last Fall was owned for some decades by a collector. When he acquired it, it was unidentified. Later he encountered a reproduction of it in a historical publication, and thus had the identification of the sitter. Each of the known copies is somewhat different from the others. In her article, Brewster reproduces the copy from the Massachusetts Historical Society. It is a paper print on a carte de visite mount bearing the imprint of San Francisco photographer William Shew, at 115 Kearny Street.

Based on this information, Brewster attributed the portrait to Shew; however, Shew is merely the copy photographer. A daguerreotype, largely out of use by the 1860s, is a unique original, not printed from a negative, so only one exists unless it is copied by camera. The carte de visite format was not in widespread use until the 1860s, and Shew was not at the Kearny address until the 1872-1879 period. So the photographer remains unidentified.

Another puzzle is posed by the early 20th century reproductions in the Bancroft Portrait File and the California Historical Society, which appear identical. These copies present a less closely cropped pose than the original daguerreotype, which is perplexing! Anita’s lap and hands are visible in the copies, but not in the daguerreotype. Although the bottom of the daguerreotype plate is obscured by its brass mat, there is not enough room at the lower edge to include these details.

How could a copy contain more image area than the original? Upon reflection, two possibilities come to mind:

1) the daguerreotype was copied in the 19th century and photographically enlarged, then re-touched or painted over to yield a larger portrait that included her lap and hand, added by an artist. This reproduction was later photographed to produce the copies in the Portrait File and CHS.

or,

2) the original daguerreotype included her lap and hand, and it was re-daguerreotyped for family members in the 1850s, perhaps near the time of Anita’s 1855 death. When the copy daguerreotypes were made, they were composed more tightly in on the sitter, omitting the lap and hands. The newly acquired Bancroft daguerreotype could be a copy of a still earlier plate – and this earlier plate could be the source of the later paper copy in the Portrait file.

This will likely remain a mystery until other variants of this portrait surface. Are there other versions of this portrait of Anita de la Guerra de Robinson to be revealed?

Reference

Brewster, Michele M. “A Californiana in Two Worlds: Anita de La Guerra Robinson, 1821–1855.” Southern California Quarterly 102, no. 2 (2020): 101–42. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27085996.

50 Years in San Francisco’s Mission District: The Archives of Acción Latina

Photographic prints and posters from the archives of Acción Latina and El Tecolote newspaper are now available for research at Bancroft Library, with an online finding aid newly published at the Online Archive of California. This is the result of the dedicated work of Isabel Breskin, an intern in Library and Information Science at the University of Washington. Below we have Isabel’s reflections on the collection, along with snapshots of a few photographs encountered while she arranged and described the files. Organizational records and other materials from Acción Latina will be made available in the coming months. -JAE

A Guest Posting by Isabel Breskin

Acción Latina is a community organization based in San Francisco’s Mission District. The roots of the organization’s work go back to 1970, when San Francisco State University journalism professor Juan Gonzalez launched a newspaper with his students. That newspaper, El Tecolote, is still published bimonthly and is now the longest-running bilingual newspaper in the country. In 1982, volunteers from El Tecolote and New College of California staged the first Encuentro del Canto Popular, a festival celebrating Latin American music. The festival became an annual event; the 41st Encuentro was held in December 2022.

The Acción Latina and El Tecolote Pictorial Archive contains thousands of photographs, hundreds of posters and artists’ prints, as well as negatives, slides, cartoons and other drawings, and digital images. The photographic print collection and the poster and artists’ print collection are now available to researchers.

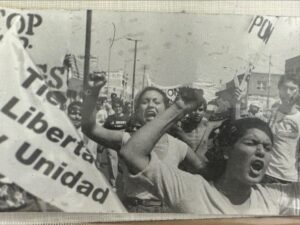

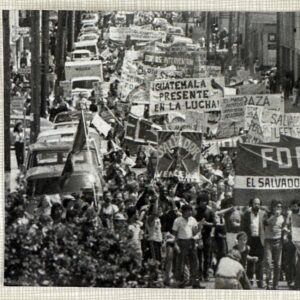

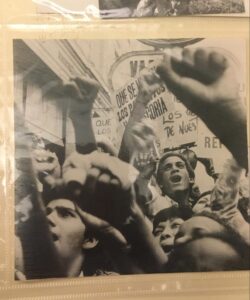

The photographs capture all aspects of life in the Mission beginning around 1970 and continuing into the first decade of the 21st century, as people took to the streets to protest and celebrate, as they went to work and school, played music and danced, painted murals and listened to poetry. I found the photographs of protests particularly compelling — and I think researchers will, too. They are both rich in information about the issues and causes of the times, and moving evidence of the passion and belief that stirred people to action.

Here are just a few snapshots I took as I worked to arrange and rehouse the photographs.

As I’ve been working on the collection I’ve been thinking about all the people involved: the many people who have been part of Acción Latina over the decades, who have lived and worked in the Mission District and have contributed to the vibrancy of its community, the photographers and artists who created these materials, and the people who will now turn to the images and learn from them.

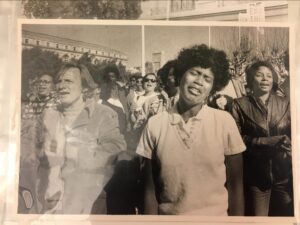

We recently had our first researcher come to use the newly available collection. He was interested in Bay Area events related to the politics and culture of Chile. Among the relevant images in the collection is this photograph.

I am struck by the look on this unknown woman’s face – she looks both tragic and absolutely determined. It is meaningful to me that her decision to go out and protest that day is being preserved in the collection, and is being recognized and honored in the work of scholars.

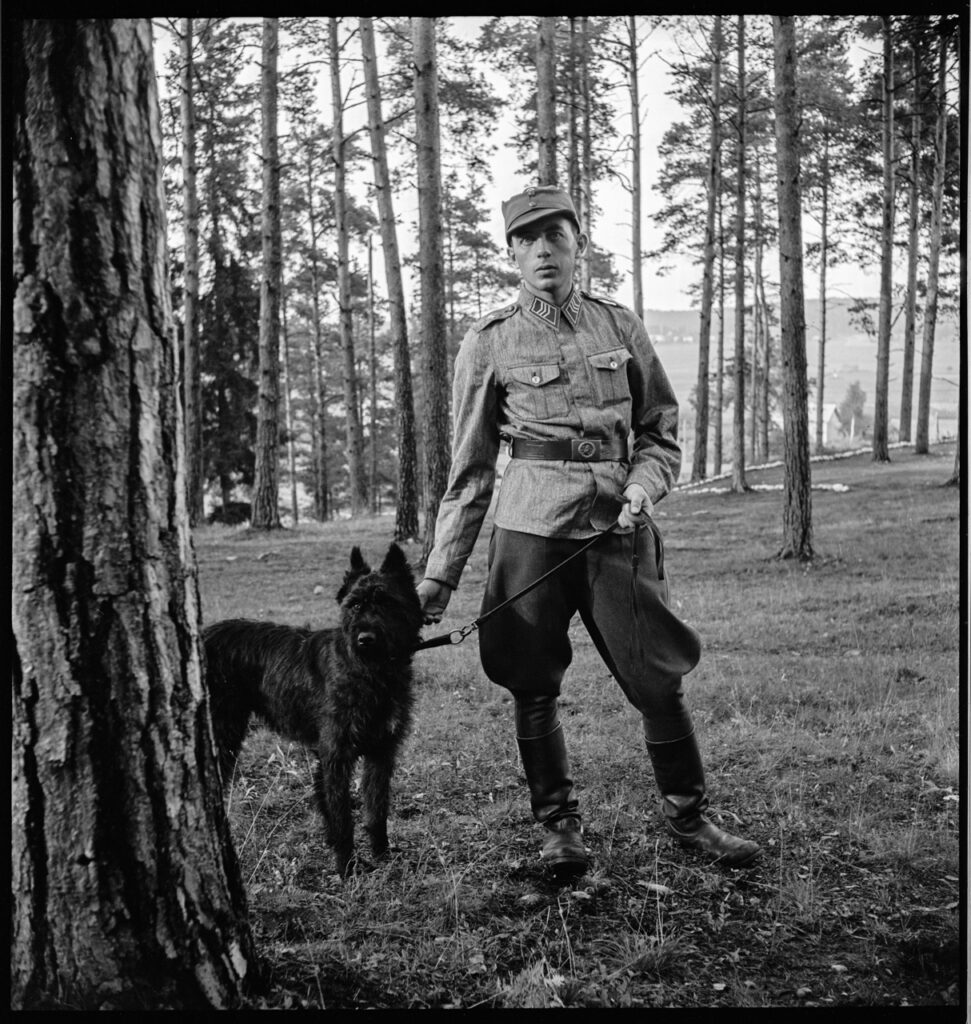

Celebrating Women’s History Month: Rare Images of the Winter War by Photojournalist Thérèse Bonney

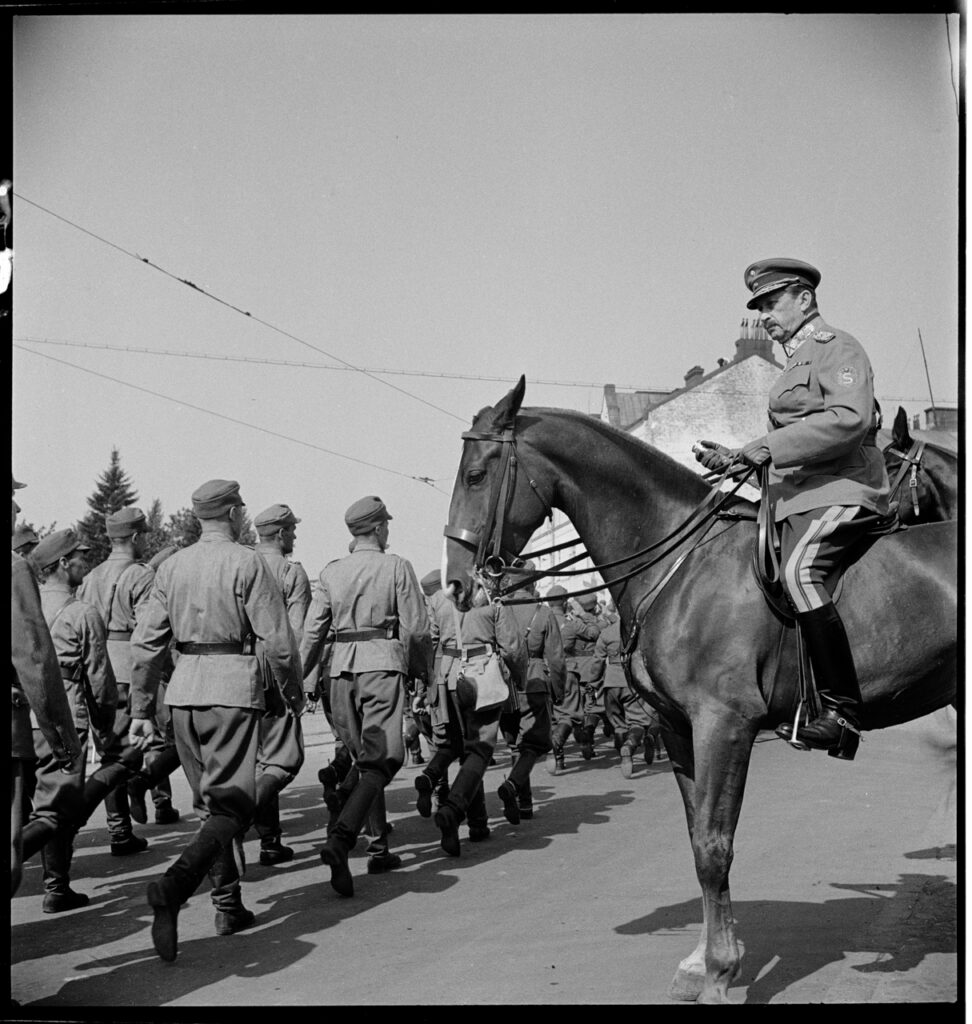

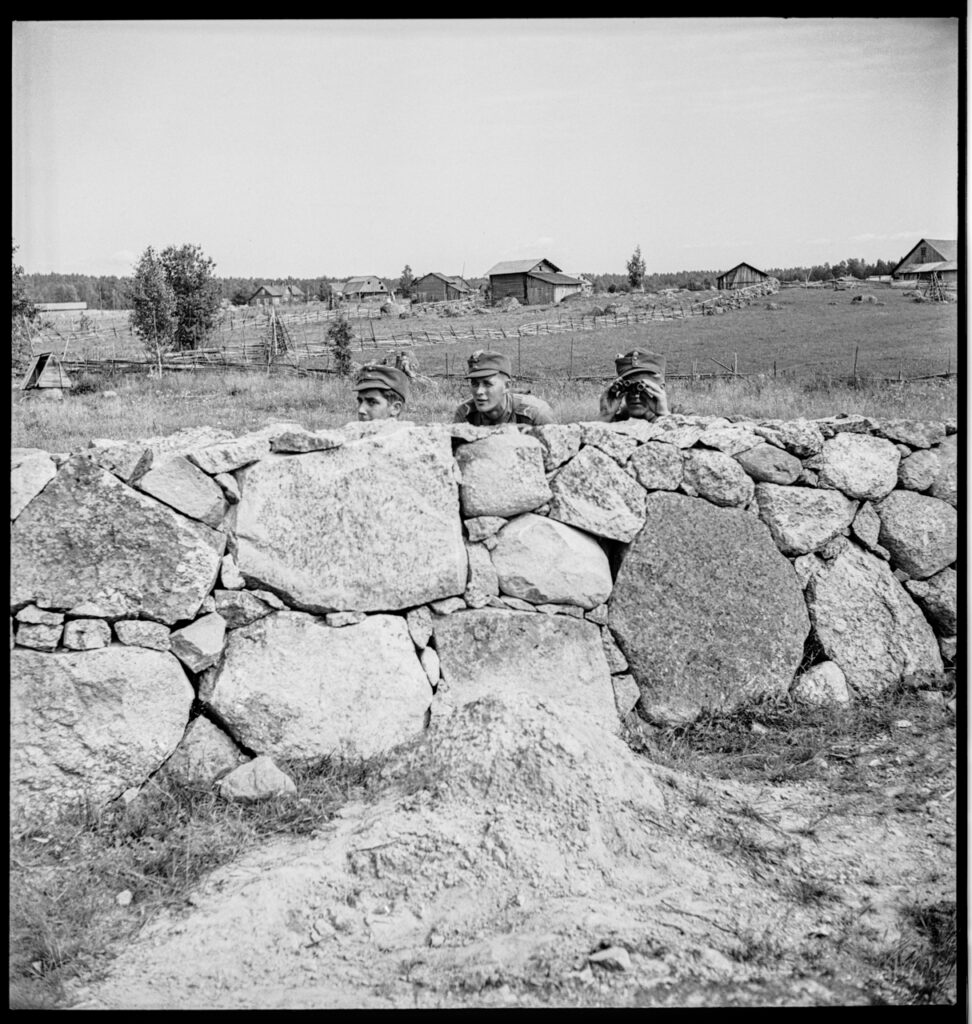

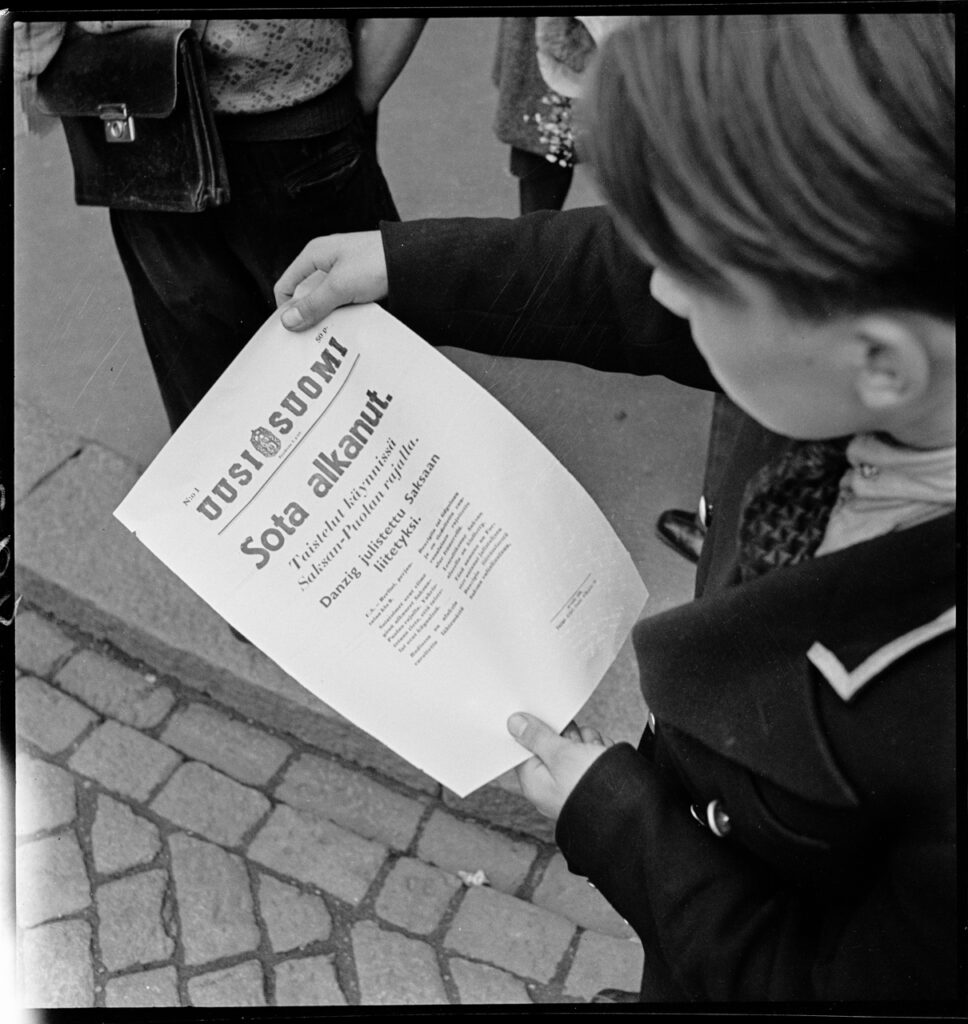

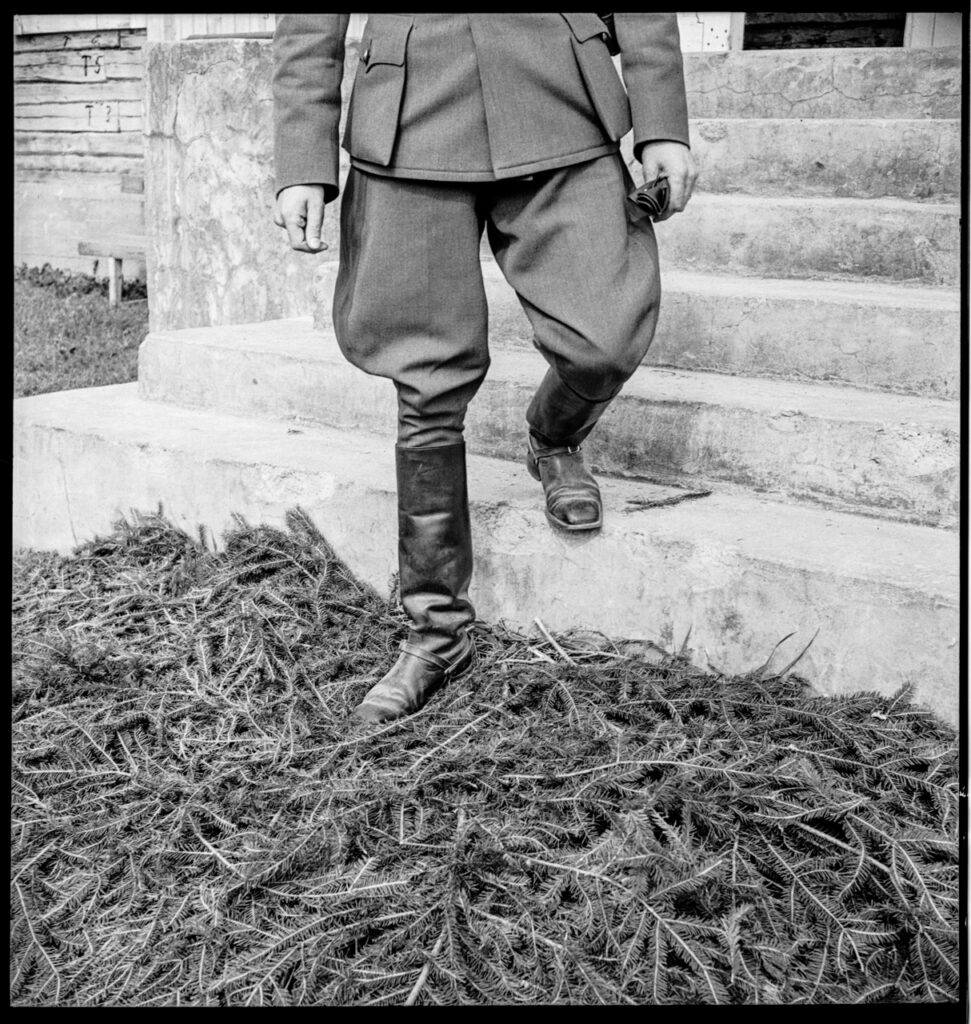

In the Autumn of 1939 Thérèse Bonney traveled to Finland to photograph preparations for the Olympic Games in Helsinki to be held the following year. Instead, she became a war correspondent. With World War II already underway, Bonney was one of few photographers in Finland as tensions with the neighboring Soviet Union grew. Bonney photographed Finnish military training operations leading up to the Soviet invasion on November 30, 1939. Throughout the ensuing Winter War she photographed civilian evacuations, relief operations, and meetings of Finnish leaders — work for which she was awarded the White Rose of Finland medal. The event would change the trajectory of her photographic career. Previously focused on French art and design, Bonney would go on to photograph throughout World War II, leaving an important record of the effect of war on civilian populations. Additional images of Bonney’s work in Europe during WWII can be seen in these previous postings: Wrapping up Women’s History Month: Selections from the Thérèse Bonney photograph collection at The Bancroft Library and Thérèse Bonney: Art Collector, Photojournalist, Francophile, Cheese Lover.

Still more is available via the Library’s Digital Collections site and the Finding Aid to the Thérèse Bonney Photograph Collection.

Enhancing Searchability While Working From Home

As staff eagerly anticipate a return to more regular on-campus work, we have a guest posting by pictorial processing archivist Lori Hines. She provides a peek at one facet of work that we have been doing remotely in 2020-2021. -JAE

A posting by Lori Hines

Working from home during the COVID-19 closure has allowed Bancroft Library pictorial unit staff to enhance descriptions of digitized items, improving online searching.

One of my recent projects was to improve the description of items from the James D. Phelan Photograph Albums, BANC PIC 1932.001–ALB , which were scanned many years ago with only brief caption transcriptions. This photograph in album 85 is identified only as “Geneveve” [sic].

Having previously worked on collections related to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, I had an idea that Geneveve, or Genevieve, could be posed at a similar event. Currently the photo is essentially unidentified and lost in the sea of images.

A photo a few places earlier in the album was identified as “Crossing Columbia River,” so that gave a clue to a possible region. A photo a few spaces later had a date of 1909, so that gave a probable date.

Doing a quick Google check, I typed in “Exposition US 1909”, and voila, I easily confirmed that Geneveve must be at the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition held in Seattle. I then added “entrance” to the search, because there appear to be turnstiles behind the arches. Google image search gave me some pretty good matches. There was one image from the Seattle Municipal Archives that showed the turnstiles with part of the arch. A couple of other pictures had better views of the arch.

Now we have a useful identification for BANC PIC 1932.001 Vol. 85:296—ALB:

Once the improved finding aid data has been uploaded, the topic will be retrievable by keyword searching at both the Digital Collections website and the Online Archive of California.

Not all of the items get this depth of attention, but this is one example that is worth the extra time. It’s been difficult being away from collections and researchers for over a year, but there is no shortage of online content with minimal identification, so there’s gratification in taking this time to make improvements.

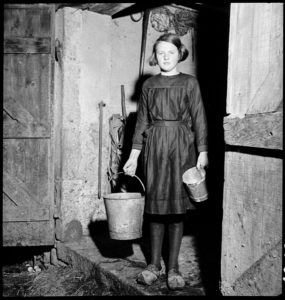

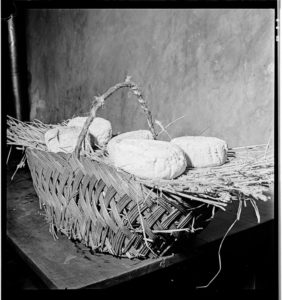

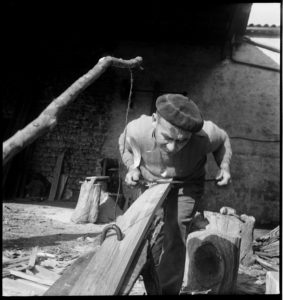

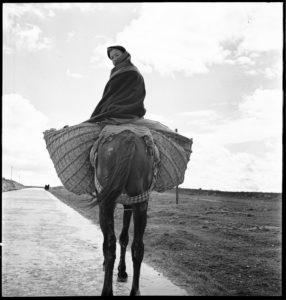

Primary Sources: Photographs from Wartime Portugal, Spain, and France

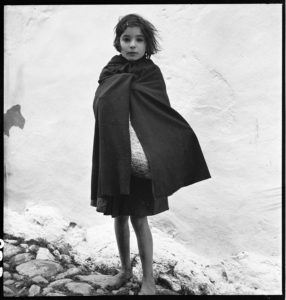

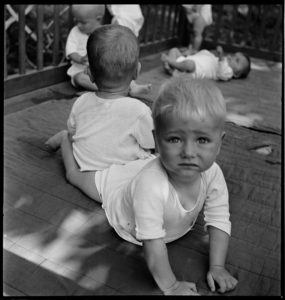

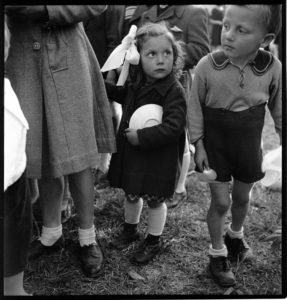

News from James Eason at the Bancroft Library: “More than two thousand digital images have just been added to the Finding Aid to the Thérèse Bonney Photograph Collection at the Online Archive of California. These images are the negative files, in their entirety, resulting from a Carnegie-funded trip Bonney made in 1941 to Portugal, Spain, and southern France. Bonney was documenting the effect of war on civilian populations, particularly children. Many images are from Franco’s Spain, with the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War starkly visible. She also took her camera to refugee camps across the French border (Perpignan, Rivesaltes, and Argelès-sur-Mer), where Spanish Republican refugees were housed at the end of the civil war, and which were being repurposed when German border closures and advances threw Europe into chaos early in World War II.”

News from James Eason at the Bancroft Library: “More than two thousand digital images have just been added to the Finding Aid to the Thérèse Bonney Photograph Collection at the Online Archive of California. These images are the negative files, in their entirety, resulting from a Carnegie-funded trip Bonney made in 1941 to Portugal, Spain, and southern France. Bonney was documenting the effect of war on civilian populations, particularly children. Many images are from Franco’s Spain, with the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War starkly visible. She also took her camera to refugee camps across the French border (Perpignan, Rivesaltes, and Argelès-sur-Mer), where Spanish Republican refugees were housed at the end of the civil war, and which were being repurposed when German border closures and advances threw Europe into chaos early in World War II.”

For more on Thérèse Bonney, see the 2018 blog posting by Marjory Bryer and Sara Ferguson “Thérèse Bonney: Art Collector, Photojournalist, Francophile, Cheese Lover”, and also Sara’s recent “Wrapping up Women’s History Month: Selections from the Thérèse Bonney photograph collection at The Bancroft Library.”

New Library Digital Collection: 1920s-1930s Leisure from the Julian P. Graham Collection of Photographic Negatives

The Bancroft Library has announced that “over 500 photographs from the Julian P. Graham collection are now available via the Library’s Digital Collections site.

“This Bancroft Library collection of film negatives from Monterey area photographer Julian Graham has been the subject of ongoing interest over the years. It documents early years of the Pebble Beach and Cypress Grove golf courses, and the recreational life of California’s “high society” of the 1920s and 1930s, chiefly around the famous Hotel del Monte. The negatives, unfortunately, are largely on hazardous nitrate-based film, so are not available for library users until digitized.”

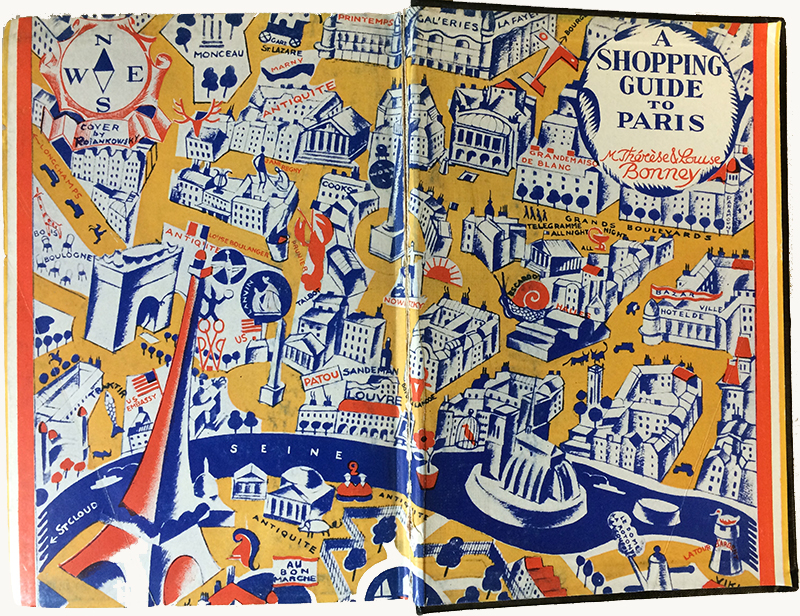

A Shopping Guide to Paris

Here’s a midsummer post to divert your attention to a fun travel guide written by an extraordinary Cal alumna (Class of 1916) and her sister Louise. In case you haven’t heard, the Thérèse Bonney papers and photographic archive have been processed and are available for use in The Bancroft Library:

- Finding Aid to the Thérèse Bonney Papers

- Finding Aid to the Thérèse Bonney Photograph Collection, circa 1850-circa 1955 (bulk 1930-1945) (2177 photos online)

Other books by Bonney can be found in the Main Stacks, or online through the HathiTrust Digital Library:

- Bonney, Thérèse. Europe’s Children, 1939 to 1943. New York: Rhode Publishing Company, 1944.

- Bonney, Thérèse, and Louise Bonney. French Cooking for American Kitchens. New York: Robert M. McBride & Co, 1929.

- Bonney, Thérèse, and Louise Bonney. A Guide to the Restaurants of Paris. New York: R.M. McBride, 1929.

Thérèse Bonney: Art Collector, Photojournalist, Francophile, Cheese Lover

Thérèse Bonney aboard the S.S. Siboney, en route to Portugal, 1941. BANC PIC 1982.111 series 3, NNEG box 49, item 19

Pioneering war correspondent and Cal grad Mabel Thérèse Bonney (1894-1978) was decorated with the Croix de Guerre and the Legion d’Honneur by the French government, and the Order of the White Rose of Finland for her work during World War II. Her photographs were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, the Library of Congress, and Carnegie Hall during her lifetime. Her work on children displaced by war spurred the United Nations to create their international children’s emergency fund, UNICEF, in 1946, and inspired the Academy Award-winning film The Search in 1948. Yet in the canon of female war photographers that includes contemporaries such as Lee Miller, Margaret Bourke-White, and Toni Frissell, Bonney rarely receives mention. Bonney was a renaissance woman whose life deserves further study, and her collections at the Bancroft Library are ripe for discovery. Manuscript Archivist Marjorie Bryer has processed The Thérèse Bonney papers, and Pictorial Archivist Sara Ferguson has digitized over 2,500 previously inaccessible nitrate negatives from the Thérèse Bonney Photograph Collection.

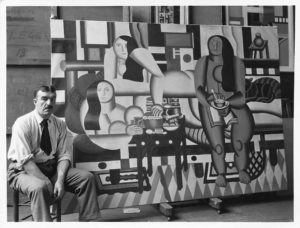

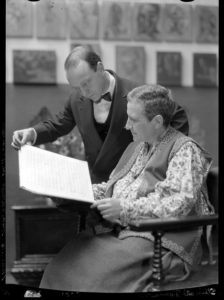

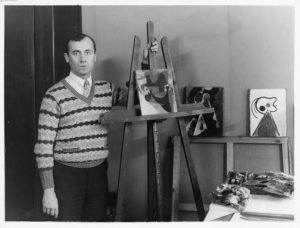

ART CONNOISSEUR

While living in Paris in the 1920s and 1930s, Bonney modeled for fashion designers like Sonia Delaunay and Madeleine Vionnet, and became friends with many of the most famous artists and writers of her day, including Raoul Dufy, Gertrude Stein, and George Bernard Shaw. In 1924 Bonney founded an international photo service that licensed images acquired in France for publication in the U.S. She was often dissatisfied with the images she distributed, and this inspired her to take up photography herself. Bonney wrote about, and took photographs of, many of the artists and writers in her life throughout the twenties, thirties, and forties.

PHOTOJOURNALISM AND WAR RELIEF EFFORTS

Bonney photographed throughout Europe during World War II, focusing on the effects of war on the civilian population. Her photographs of children were particularly moving and resulted in her most famous work, the exhibit and book, Europe’s Children. Bonney was actively involved with relief efforts after the war, particularly in the Alsace region of France. She also founded a number of organizations dedicated to promoting friendship between citizens of France and the United States, and improving Franco-American political relations. One effort, the Chain d’Amite, encouraged French families to open their homes to American G.I.s; another, Project Patriotism, inspired airmen who were shot down in France to help the families that had rescued them. Project Patriotism eventually spread to other European countries, including the Netherlands. Marjorie’s father-in-law, Peter, was a teenager when Germany invaded the Netherlands during the war. He was sent to live with relatives in the Dutch countryside so he wouldn’t be conscripted. One of Peter’s most moving stories was about the American pilot his family hid when his plane crashed on the family farm. Bonney’s papers include many poignant letters from U.S. soldiers and, while processing the collection, Marjorie wondered what this airman from Brooklyn might have written about his experiences with his Dutch “family.”

LOVER OF CHEESE

Bonney’s many interests included food and cooking. She and her sister, Louise, wrote a guide to Paris restaurants and a cookbook, French cooking for American kitchens. Her papers include her research on cheese, which she referred to as “Project Fromage.” Series 7 of Bonney’s papers include meticulous notes on various cheeses from France and the Netherlands, “technical” correspondence about cheese, and materials related to tyrosemiophilia — the hobby of collecting cheese labels.

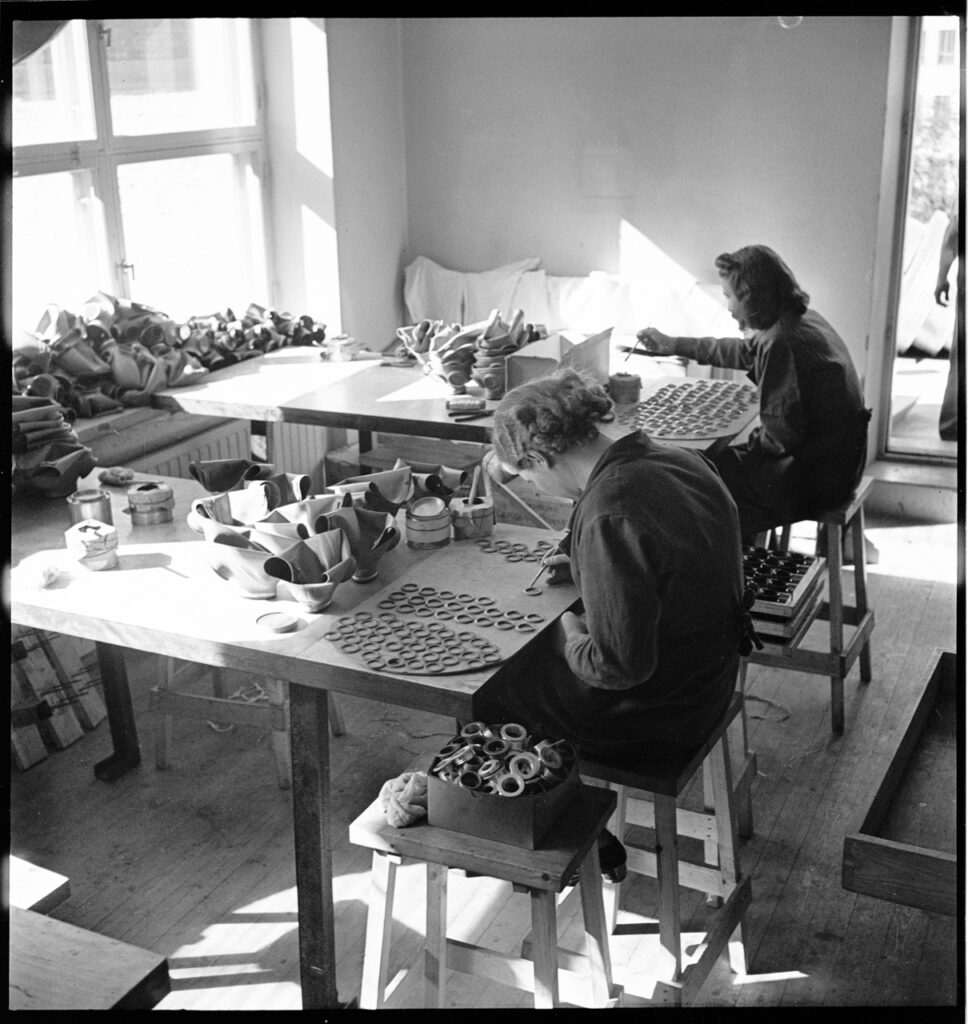

EVERYDAY PEOPLE AND LIFE DURING WARTIME

Bonney documented daily life during wartime across Europe. She recorded entire communities — their families, customs, and industries, their artists and politicians, their schools, and their churches. Her papers and photographs show not only the horrors of war but the hope and perseverance of those who lived through it.

NOW AVAILABLE AT THE BANCROFT LIBRARY!

Newly digitized portions of the pictorial collection include Series 6: France, Germany 1944-1946. This series includes photographs of concentration camps Vaihingen, Buchenwald, and Dachau; Displaced Person camps; Neuschwanstein Castle; and Hermann Göring’s Collection of art looted by the Nazi’s. It also includes many images of the heavily bombarded town of Ammerschwihr in Alsace, France and war relief efforts there. Future digitization efforts will focus on Series 3, Carnegie Corporation Trip: Portugal, Spain, France 1941-1942. This series consists of images taken while on a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York to document the effects of war on civilian populations. It includes images of military personnel, civilian industries, and Red Cross operations. Famous personalities pictured in this series include Pierre Bonnard, Henri Matisse, Georges Roualt, Gertrude Stein, Philippe Petain, Raoul Dufy, and Aristide Maillol.

Bonney’s papers help contextualize her photographs. They include correspondence; personal materials; her writings (autobiographical and articles about others); and her files on World War II, Franco-American relations, art, fashion, photography, and cheese.

Both collections are open for research:

Finding Aid to the Thérèse Bonney Photograph Collection, circa 1850-circa 1955 (bulk 1930-1945)

Finding Aid to the Thérèse Bonney Papers

— Marjorie Bryer and Sara Ferguson

Revista Matador

Through La Fábrica—the Madrid-based publishing house he also directs, journalist Alberto Arnaut aims to incite a cultural debate in Matador, or in his own words a “campo de batalla” (battlefield) for ideas in all genres. The work of painters, sculptors, photographers, novelists, poets, playwrights, essayists, philosophers, architects, filmmakers, actors, chefs, musicians, fashion designers, and more adorn the pages of the lavish folio-size issues. Published annually since 1995 beginning with the letter A, the publishers are committed to completing 28 issues in 2022 when they reach the letter Z.

It is difficult to describe what takes place in Matador until you put your hands on an issue. Other than the dimensions, no issue is alike and each takes on a distinct theme. The magazine is predominantly visual with an emphasis on creators from the Iberoamerican world such as artists Miguel Barceló, Luis Gordillo and Eduardo Chillida; photographers Francesc Català-Roca, Xavier Miserachs, Ramón Masats; and filmmakers Bigas Luna and Gonzalo Suárez. However, contributions from all the continents establish an international dialogue. The words of contemporary fiction writers such as Javier Marías, Juan Goytisolo, Elena Poniatowska, and Juan Villoro engage with the deceased such as Rafael Alberti, Clarice Lispector, José Saramago and others. The texts of French theoreticians Hélène Cixous and Paul Virilio and the Department of Spanish Portuguese’s own Alex-Saum Pascual can also be encountered in Matador.

This year, the Art History/Classic Library was able to acquire all issues to date (A-T) as a joint purchase with the Romance Languages Librarian and is now one of only three libraries in California with a full-run and subscription.

Matador. Madrid: La Fábrica, 1995-

Matador. Madrid: La Fábrica, 1995-

Art History/Classics f NX456 .M368

1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition: Stories through Photographs

A guest posting by Seamus Howard, Student Archival Processing Assistant in the Pictorial Unit, Bancroft Library

What makes a photograph good?

As a student working in the Bancroft Pictorial Unit, I’ve been going through hundreds and hundreds of photographs daily. I’ve seen my share of good and bad photos.

One might stand out as “good” due to the lighting, crisp focus, correct staging, and exposure — good cropping perhaps, or just clarity of subject. Ultimately, the answer is a combination of factors, and can be completely subjective.

For me, the most important factor is moment.

The 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition was full of special moments captured in photographs which continue to shed light on the character and tone of the United States during the early 20th century.

One special moment was former President William Howard Taft visiting the P.P.I.E.

Working to re-house and inventory about 6,700 photographic prints in large, brittle ledger books, I’ve encountered numerous shots of this visit, thoroughly recorded by the Cardinell-Vincent Company, the exposition’s official photographers.

President Taft was an early supporter of the exposition, declaring in early 1911 that San Francisco would be the official home of the fair. He attended the groundbreaking eight months later and returned to San Francisco in 1915 to see the fair in all its glory.

Taft’s visit to the fair was seemingly a large event. He was accompanied wherever he went, soldiers or guards escorting him from building to building. Taft continued to be a very important person at this time. He had lost his reelection to Wilson in 1912, and returned to Yale as a professor of law and government.

Taft visited many of the fair’s popular buildings and exhibits, including the Japanese Pavilion, Swedish Building, Norway Building, and the art gallery and courtyard of the French Pavilion. He met foreign representatives, fair officials, and experienced much of what the fair had to offer.

And President Taft experienced the unique blend of cultures and stories the fair provided. Here, in my favorite photograph of Taft’s time at the fair, he walks through a hall lined with busts in the Swedish building, flanked by guards. Taft seems enveloped by the art and is perfectly framed between his escorts and the lines of busts, drawing your eye towards Taft at the center. This moment makes a great photograph.

The Bancroft Pictorial team continues to house and describe the collection, and will update this blog with more photographs and details as we progress. Stay tuned!