Tag: New Acquisitions

New Rare Photography Book Acquisitions from Richard Sun

Have a look at this selection of rare and out of print photography books. This is only a part of a recent, generous donation from Richard Sun. These books are located in the Art History/Classics Library within the Doe Memorial Library. Click on the titles to view their catalog records in UC Library Search.

Looking for Alice Lost Coast My Dakota

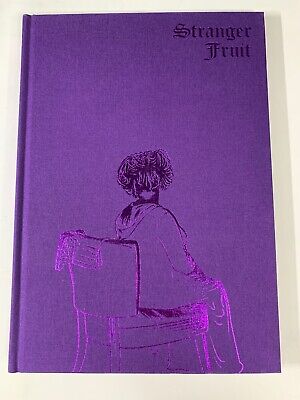

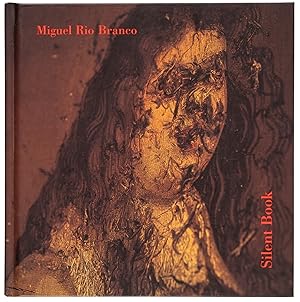

The Epilogue Stranger Fruit Silent Book

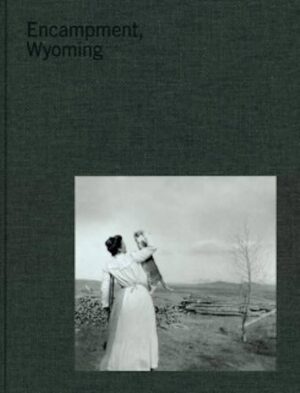

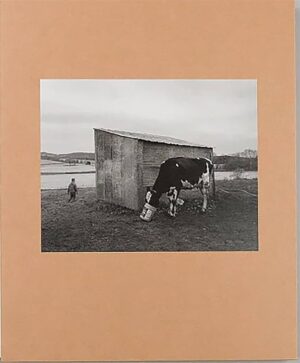

In Search of Frankenstein Encampment Wyoming Dormant Season

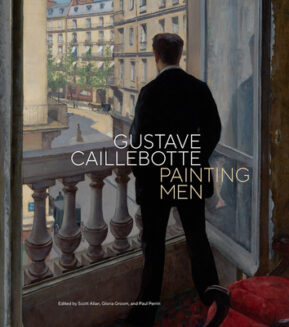

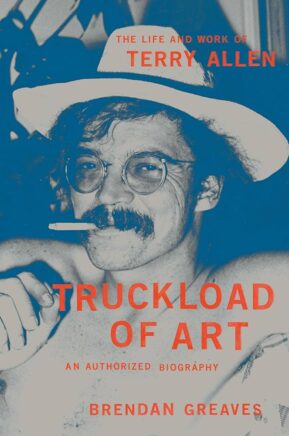

New York Times Best Art Books of 2024

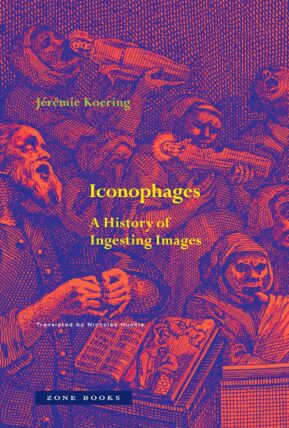

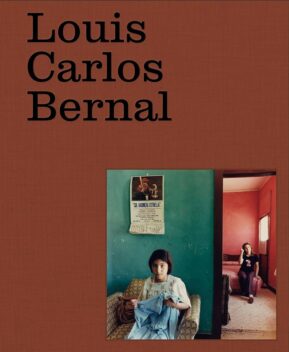

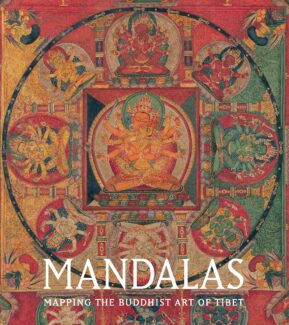

Check out some of the New York Times “Best Art Books of 2024.”

A Book about Ray At the Louvre Atlas of Never Built Architecture Emergency Money

Exit Interview Iconophages If the Snake Louis Carlos Bernal

Mandalas Painting Men Truckload of Art Hello We Were …

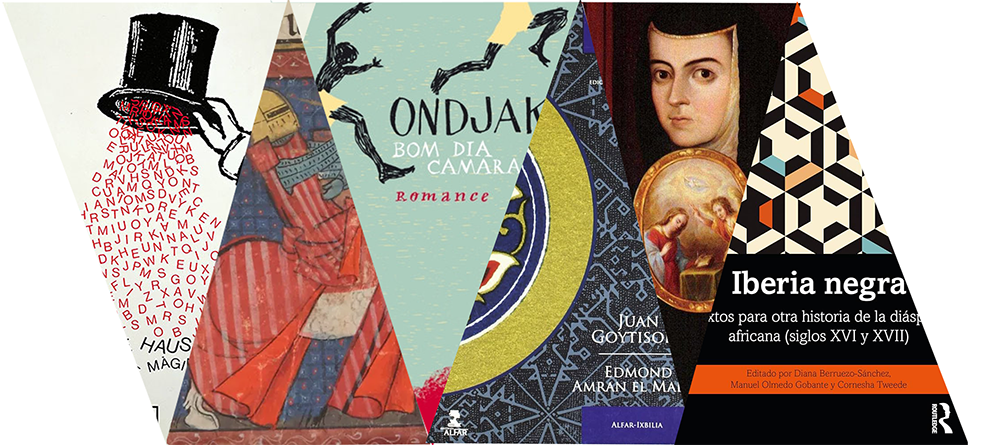

New Library Guide for Iberian Literatures

Today, we are launching a new library research guide for Iberian Literatures & Criticism. The new guide will improve navigation and discovery in UC Berkeley’s vast literature collection in Romance languages, mostly found in a classification commonly known as the PQs. Over the course of the past year, we have critically reviewed the former guides, weeded outdated resources, and replaced them with more current content with links to digital resources when available.

This literary research guide, like the others for Italian and French & Francophone literatures launched last year, is now benefiting from the LibGuides platform, which makes it much easier to revise than the former PDFs. The guide is structured by sections for article databases, general guides and literary histories, reference tools, poetry, theater & performance, and literary periods. In addition to literature in Spanish and Portuguese, it also includes less commonly taught literatures and languages such as Catalan, Galician, Basque, Arabic, Ladino, and more. There is also a new section for Luso-African and Hispano-African literature.

The online guide also interfaces seamlessly with related guides published by the UC Berkeley Library. For example, on the home page, there is a prominent link to the online list of recently acquired publications on the general Spanish & Portuguese guide, making it even easier to stay current on new books in all of the call number ranges.

Because the guides are much easier to update, they encourage user interaction and invite community suggestions for inclusion (or deletion).

When you have time, please take a look at this new resource and let us know what you think.

Claude Potts, Romance Languages Librarian

Cameron Flynn, RLL Doctoral Candidate

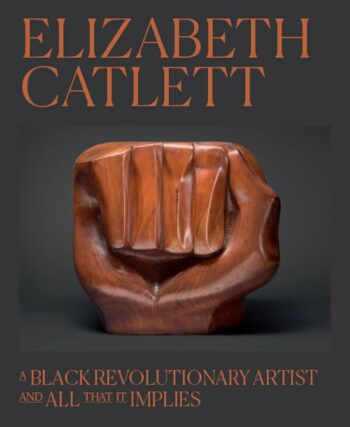

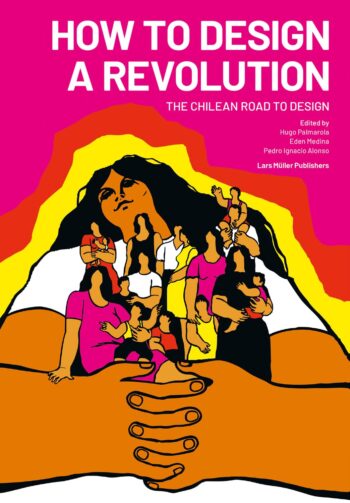

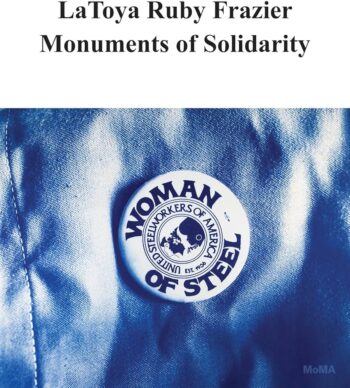

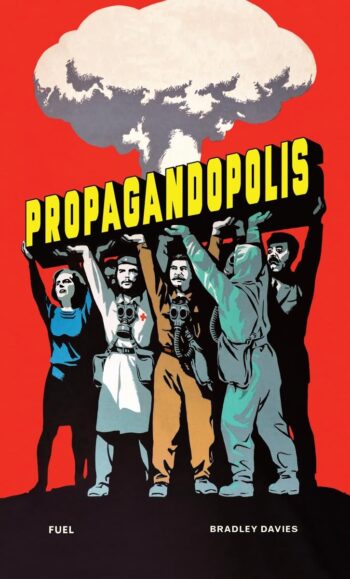

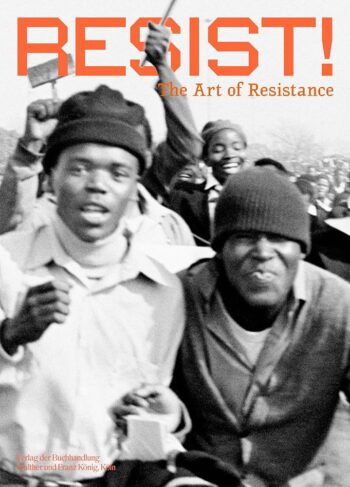

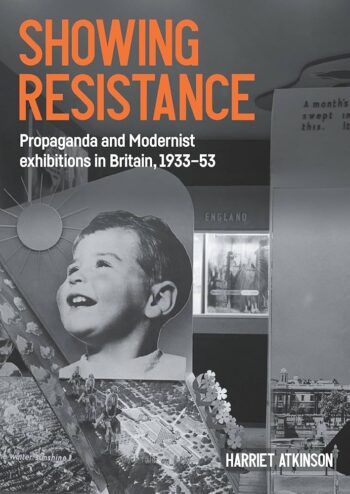

Art as Resistance

Check out these, and other books that explore and represent the use of art as social and political resistance, currently on display in the Art History/Classics Library.

Elizabeth Catlett How to Design a Revolution LaToya Ruby Frazier

Propagandopolis Resist! The Art of Resistance Showing Resistance

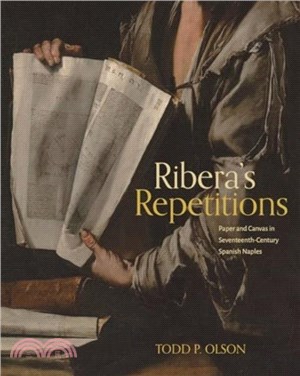

New Publication from Art History Faculty Todd Olson

Check out Professor Todd Olson’s newest publication, Ribera’s Repetitions: Paper and Canvas in Seventeenth-Century Spanish Naples

“Todd Olson carefully considers the diverse contexts for Ribera’s artistic practice, such as empire-building, materiality, and myth, and thus assesses the complexity of Ribera’s creativity through the lenses of repetition, rotation, and experimentation. This novel, interdisciplinary study reexamines the originality of Ribera’s praxis as engaged in a visual culture shaped by science, history, and belief in early modern Naples.”

“Much more than a mere study on Jusepe de Ribera, Olson’s book is an essay on materiality, technique, and their meanings; on imperial circulation and its discontents; and on knowledge, memory, and loss. This piece of cultural history, never losing touch with the artworks and their visual particularities, is beautifully written and at times moving, reminding us of the potentialities of art history as a literary and philosophical genre.”

-From Penn State University Press

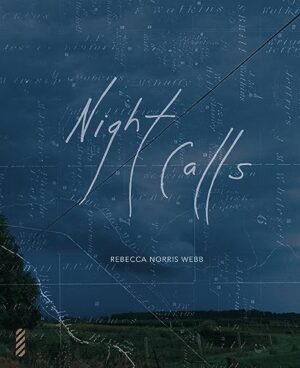

Rare Photography Book Donations from Richard Sun: Part 2 of 3

These rare books are part of a generous curated donation from Richard Sun. They may be viewed in the Art History/ Classics Library. Request them in advance as they may be stored off site.

Zaido The Earth is Only a Little Dust Under our Feet Night Calls

As it was Given to Me Dream Children Jamais je ne t’oublierai

The Hidden Mother Landing Lights Park Hello My Name Is

Rare Photography Book Donations from Richard Sun: Part 1 of 3

Here are a selection of recently received donations of rare photobooks generously curated and donated by Richard Sun. They may be viewed in the Art History/ Classics Library. Please request in advance, as they may be located off site.

50% the Visible Woman Agata An Exorcism

Aeronautics in the Backyard Gretta Margins of Excess

New Alumni Publications in Art History

Check out these new publications by U.C. Berkeley Art History Alumni, available through UC Library Search.

The Death of Myth on Roman Sarcophagi: Allegory and Visual Narrative in the Late Empire, by Mont Allen.

Rethinking the Public Fetus: Historical Perspectives on the Visual Culture of Pregnancy, by Jessica M. Dandona.

Toshiko Takaezu; Worlds Within, essay by Diana Greenwold.

Smithsonian Asian Pacific American History Art and Culture in 101 Objects, essay by Diana Greenwold.

Female Cultural Production in Modern Italy. Literature, Art and Intellectual History, by Sharon Hecker (ed.).

Collective Body: Aleksandr Deineka at the Limit of Socialist Realism, by Christina Kiaer.

Henry van de Velde: Designing Modernism, by Katherine Kuenzli.

Henry van de Velde: Selected Essays 1889-1914, by Katherine Kuenzli.

Exquisite Dreams: The Art and Life of Dorothea Tanning, by Amy Lyford.

Albrecht Durer and the Depiction of Cultural Differences in Renaissance Europe, by Heather Madar.

Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction, essay by Bibiana Obler.

Expressionists: Kandinsky, Munter and the Blue Rider, essay by Bibiana Obler.

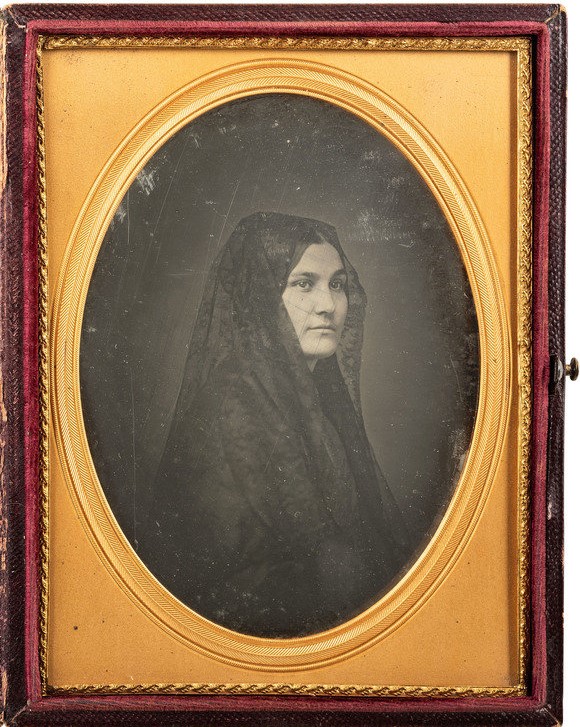

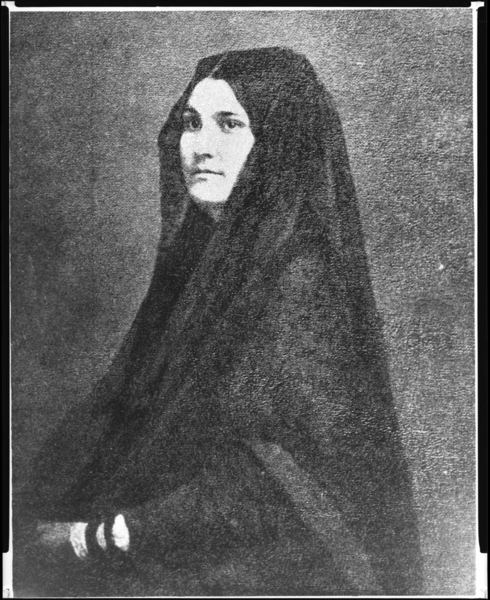

A Californiana Returns to the Bay Area: Ana María de la Guerra de Robinson

Women’s history month is the perfect time to announce an exciting addition to Bancroft Library’s collection of daguerreotype portraits. At the end of 2023 the library was able to acquire a beautiful 1850s portrait of a Californiana: doña Ana María de la Guerra de Robinson, also known as Anita.

In this large (half plate format) daguerreotype of about 1850-1855, Anita wears a lace mantilla, in the Spanish fashion. A beautiful large daguerreotype like this was an extravagance at the time, and the portrait is all the more evocative because Anita, tragically, died within a few years of its creation.

Fortunately, quite a bit is known about her life. Anita was born into the prominent de la Guerra family of Santa Barbara in 1821 -– the same year the Spanish colonial period ended and control by an independent Mexico began. She was married at age 14, to an American trader and businessman named Alfred Robinson, 14 years her senior. This wedding is described in Richard Henry Dana’s Two Years Before the Mast, so we have an unusually detailed account of what was a grand occasion.

She and her husband snuck away from her family in 1838, leaving their baby daughter behind with her grandparents. Anita, age 15, wrote ”We have left the house like criminals and left here those who have possession of our hearts.” Various writers have interpreted these circumstances differently but, whatever the reason for this strange departure, Anita spent the next 15 years in Boston and the East Coast, seemingly eager to return home, but continually disappointed in the hope. It is hard to imagine that her life was entirely happy, in spite of the steady growth of her family and the prosperity and social prominence the Robinsons and de la Guerras enjoyed.

Having borne seven children, and having witnessed from afar (and apparently mourned) the transition of her homeland from Mexican territory to American statehood, Anita finally returned to California in the summer of 1852. It is likely she had her daguerreotype portrait taken at this time, in San Francisco, although it could have been taken back east. Sadly, she lived just three more years in California, dying in Los Angeles in November 1855, a few weeks after giving birth to a son. She is buried at Mission Santa Barbara.

A study of Anita’s life was published by Michele Brewster in the Southern California Quarterly in 2020 (v.102 no. 2, pg. 101-42) . Read more of her story!

With such a fascinating and relatively well-documented life, we’re thrilled to have Anita’s beautiful portrait here at Bancroft. It joins other de la Guerra family portraits, as well as numerous papers related to the family, including “Documentos para la historia de California” (BANC MSS C-B 59-65) by her father, José de la Guerra y Noriega.

Two of Anita’s sisters had “testimonias” recorded by H.H. Bancroft and his staff; one from Doña Teresa de la Guerra de Hartnell (BANC MSS C-E 67) and another from Angustias de la Guerra de Ord (BANC MSS C-D 134).

Anita’s daguerreotype itself presents an interesting conundrum and history. The photographer is unknown, as is common with daguerreotypes. The portrait has been known over the years because later copies exist in several historical collections, including the California Historical Society, the Massachusetts Historical Society, and Bancroft Library’s own Portrait File.

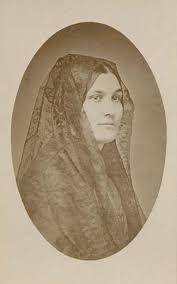

The daguerreotype acquired last Fall was owned for some decades by a collector. When he acquired it, it was unidentified. Later he encountered a reproduction of it in a historical publication, and thus had the identification of the sitter. Each of the known copies is somewhat different from the others. In her article, Brewster reproduces the copy from the Massachusetts Historical Society. It is a paper print on a carte de visite mount bearing the imprint of San Francisco photographer William Shew, at 115 Kearny Street.

Based on this information, Brewster attributed the portrait to Shew; however, Shew is merely the copy photographer. A daguerreotype, largely out of use by the 1860s, is a unique original, not printed from a negative, so only one exists unless it is copied by camera. The carte de visite format was not in widespread use until the 1860s, and Shew was not at the Kearny address until the 1872-1879 period. So the photographer remains unidentified.

Another puzzle is posed by the early 20th century reproductions in the Bancroft Portrait File and the California Historical Society, which appear identical. These copies present a less closely cropped pose than the original daguerreotype, which is perplexing! Anita’s lap and hands are visible in the copies, but not in the daguerreotype. Although the bottom of the daguerreotype plate is obscured by its brass mat, there is not enough room at the lower edge to include these details.

How could a copy contain more image area than the original? Upon reflection, two possibilities come to mind:

1) the daguerreotype was copied in the 19th century and photographically enlarged, then re-touched or painted over to yield a larger portrait that included her lap and hand, added by an artist. This reproduction was later photographed to produce the copies in the Portrait File and CHS.

or,

2) the original daguerreotype included her lap and hand, and it was re-daguerreotyped for family members in the 1850s, perhaps near the time of Anita’s 1855 death. When the copy daguerreotypes were made, they were composed more tightly in on the sitter, omitting the lap and hands. The newly acquired Bancroft daguerreotype could be a copy of a still earlier plate – and this earlier plate could be the source of the later paper copy in the Portrait file.

This will likely remain a mystery until other variants of this portrait surface. Are there other versions of this portrait of Anita de la Guerra de Robinson to be revealed?

Reference

Brewster, Michele M. “A Californiana in Two Worlds: Anita de La Guerra Robinson, 1821–1855.” Southern California Quarterly 102, no. 2 (2020): 101–42. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27085996.

Celebrating Black History Month in the Romance Languages

Contemporary Black, African, and African diaspora writers across the world are redefining literature and criticism in French, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese. Here are some noteworthy books in their original languages recently acquired by the UC Berkeley Library. Translations into English may also be available for some of the better known.

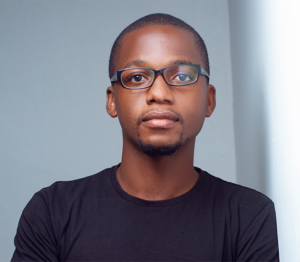

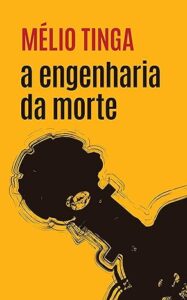

Mélio Tinga

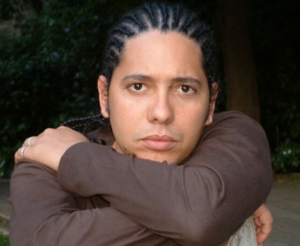

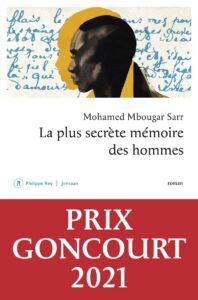

Mohamed Mbougar Sarr

Léonora Miano

Cristina Roldão et al.

David Pullins

Aïssa Maïga et al.

Doris Wieser & Jessica Falconi, orgs

Léonora Miano

Ubah Cristina Ali Farah

Alain Mabanckou, Pascal Blanchard, et Abdourahman Waberi

Evelyne Trouillot

Dimitry Elias Léger

Tierno Monénembo

Djaïli Amadou Amal

Nétonon Noël Ndjékéry

Igiaba Scego

Pierre Singaravélou

Carlos Martens Bilongo

Dorothy Odartey-Wellington, ed.

Camilla Hawthorne

Inocência Mata et al., eds.

Please also see the related English literatures post for Black History Month 2024 and the Black History at Cal library research guide.