Tag: BL Europe

Modern Hebrew

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

ורבים מצאו שראוי לתמוך בה ואין פוצה פה כנגד המצוה הזאת. אפס לכלל מעשה לא באו, חס ושלום שאנשי בוצץ מתרפים מדבר מצוה להתעסק בה, אבל כלל זה מסור בידם כל שאפשר לעשותו מחר אפשר לדחותו גם למחרתיים ויש מחרתיים לאחר זמן. וכשבאו ואמרו לפרנס החודש קריינדל טשרני גוועת ברעב ענה ואמר באמת באמת קריינדל טשרני גוועת ברעב.

And many saw fit to support her and none objected to this mitzvah. But they failed to act. Heaven forbid that the people of Buczacz would neglect performing a mitzvah, but this was their fixed rule: whatever can be done tomorrow can be put off to the day after tomorrow, and there is another tomorrow after that. And when they came and said to the month’s community head, “Kreindel Tcharny is dying of hunger,” he responded, “Really, really, Kreindel Tcharny is dying of hunger.” (trans. Robert Alter)

The novella And the Crooked Shall be Straight, which appeared in 1912, a year before the 24-year-old Agnon left Palestine for what would prove a decade-long stay in Germany, established his reputation as a major new voice in Hebrew literature. In it, he perfected his signature style, a supple and resonant synthesis of early rabbinic Hebrew, the Hebrew of the medieval commentaries, and the language of Early Modern pious literature. The power of the story came across in translation as well: Walter Benjamin, destined to become one of the most original critics of his age, read it in the 1919 German version together with other stories and deemed Agnon a great writer.

The plot is one that had some currency among European writers—one thinks of Balzac’s Colonel Chabert, the story of an officer in Napoleon’s army presumed dead in battle who after some years returns home to find his wife married to another man, like the protagonist of Agnon’s novella. The abundant deployment of traditional Hebrew sources here is shrewdly ironic. The title itself, a quotation from Isaiah 40:4, is turned back on itself because in the story nothing tragically bent will be made straight. The citation of a well-known talmudic dictum, “A poor man is as good as dead,” acquires a new, macabre meaning. The original sense is that a poor man is so miserable and so ill-regarded that he might as well be dead. But Agnon’s Menashe Haim—his name means “life-forgetter”—becomes a living dead man. After he sells his mendicant’s rabbinic letter of recommendation, the buyer is found dead with the seller’s name on the letter; his grave is marked with a tombstone bearing Menashe Haim’s name; his wife, who had been childless, has a baby with her new husband; and Menashe Haim, discovering this, retreats to olam hatohu, a borderline realm between life and death, in the end living in a cemetery. All this is a naturalistic adaptation of Gothic fiction, to which Agnon was drawn, populated by wandering souls, revenants, and ghosts. Perhaps the one unironic allusion to a traditional text is to Qohelet (Ecclesiastes), recurring in the story. At one point, the narrator says, “As the rhapsode (hameilitz) Schiller has said, “A generation comes and a generation goes but hope endures forever.” Whether Schiller actually said this, a one-word substitution has been made in the quotation of Qohelet 1:4, which reads, “A generation comes and a generation goes but the world endures forever.” In Menashe Haim’s story, hope is a mockery. One may recall Kafka’s somber remark, “There is hope but not for us.”

Contribution by Robert Alter

Emeritus Professor of Hebrew and Comparative Literature,

Department of Near Eastern Studies

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: והיה העקוב למישור [Ṿe-hayah he-ʻaḳov le-mishor]

Title in English: And the Crooked Shall be Straight

Author: Agnon, Shmuel Yosef, 1887-1970; Illustrated by Joseph Budko.

Imprint: Berlin, Jüdischer Verlag, 1919.

Edition: n/a

Language: Modern Hebrew

Language Family: Afro-Asiatic, Northwest Semitic

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Maryland, College Park)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011626839

Other online editions:

- Und das Krumme wird gerade: Geschichte eines Menschen mit Namen Menaschen Chajim … / das hat verfasst und hat es aufgeschrieben G.S. Agnon; [aus dem Hebräischen von Max Strauss]. Berlin: Jüdische Verlag, 1920.

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Ṿe-hayah he-ʻaḳov le-mishor / be-tseruf heʻarot, beʼurim u-marʼe meḳomot me-et Naftali Ginaton. Yerushalayim: Shoḳen, 1965.

- Sipurim: Ṿe-hayah he-ʻaḳov la-mishor; Tehilah. Yerushalayim: Shoḳen, 723, 1963.

Explore Modern Hebrew language and literature at UC Berkeley:

- Learn Hebrew with Rutie Adler

- Study Modern Hebrew literature with Chana Kronfeld

- Choose the undergraduate Minor in Hebrew

- Pursue advanced study in UCB’s Near Eastern Studies and Comparative Literature graduate programs in Hebrew and Hebrew literature

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Welsh

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Saunders Lewis, the celebrated Welsh writer, public intellectual, and nationalist, delivered his rousing speech, “Tynged yr Iaith” (“The Fate of the Language”) on BBC on February 13, 1962. Lewis was a passionate advocate for the Welsh language and the culture it embodies, and sought to both revive the language and craft his own literary contributions in it.

In the speech, Lewis lays out the historical suppression of the Welsh language and defines its history as one not only of linguistic or cultural importance, but one firmly motivated by political ends. This has led to the current “crisis” of the late 20th century, a time when, based on a decline of Welsh speakers in a recent census, Lewis views Welsh to be a fading language of a minoritized population. He suggests that although the English were responsible for Welsh’s marginalization, more recently it is the Welsh themselves who have allowed the language to fade, and it is their responsibility to save it.

Lewis was born in Wales in 1893 and spoke Welsh growing up. He fought in World War I and served alongside Irish soldiers, which may have influenced his ideas about nationalism and language. He went on to become a professor of literature and an activist, forming a nationalist party for Wales, Plaid [Genedlaethol] Cymru, that is still active today. As a writer, he is most known for his Welsh-language dramatic plays, but he also wrote extensively in fiction, poetry, literary criticism, and essays. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in 1970, and his legacy lives on as one of the most important figures in Welsh literature and culture.

Contribution by Stacy Reardon

Literatures and Digital Humanities Librarian, Doe Library

Special thanks to Kathryn Klar

Lecturer Emerita, Celtic Studies Program

~~~~~~

Title: Tynged yr Iaith

Title in English: Fate of the Language

Author: Lewis, Saunders, 1893-1985.

Imprint: February 13, 1962

Edition: 1st

Language: Welsh

Language Family: Indo-European, Celtic, Brittonic

Source: BBC Radio Cymru

URL: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00d4lk2 [only transcript available in U.S.]

Other online editions:

- “Saunders Lewis – Tynged yr Iaith ” in four parts with transcription in Welsh, YouTube. (accessed 8/5/2020)

- “Tynged yr Iaith / The Fate of the Language Saunders Lewis” with English textual translation, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BnqylLCe85Q (accessed 8/5/2020)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Presenting Saunders Lewis edited by Alun R. Jones and Gwyn Thomas. Cardiff, University of Wales Press, 1973. Includes the English translation of “Tynged yr Iaith.”

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Finnish

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

The Kalevala, the Finnish national epic, is a collection of folklore stories, much in the spirit of the German Nibelungenlied or Old English Beowulf. The Kalevala starts with the origins of the earth, its first people, spirits and animals, and ends with the departure of the main protagonist and the arrival of a “golden child”, a new era.

The Kalevala is based on poetry called runos or runes, collected and compiled by Elias Lönnrot, a countryside doctor who had a keen interest in linguistics and, especially, in oral folklore. He set out for his first of many oral folklore collection journeys in the early 1830s and journeyed to the Karelian Isthmus, to areas that were then and are also nowadays part of Russia. The areas he visited were populated by Finnish speakers and considered as part of Finland by many. Lönnrot’s method of collection was simple: he listened to local singers and wrote down what he heard. In the process of compiling the transcripts, he surely took liberties to compose parts himself as well.

When Lönnrot started the Kalevala project there was no sovereign nation called Finland. Before becoming independent in 1917, the area we know now as Finland was under either Swedish or Russian rule for centuries. In Lönnrot’s times, Finland was an autonomous Grand Duchy of Russia. National romantic ideas of one national hailing from shared, mystical origins were no inventions of Lönnrot’s—quite the contrary. Winds of changes were blowing across Europe as Lönnrot walked along the Russian Isthmus collecting folklore. Europe was a turmoil of revolutions.

Many artists and thinkers in the Grand Duchy of Finland were excited about the Finnish language, culture, and the budding ideas of an independent nation. A national epic seemed needed, almost necessary, and in many ways it was perhaps perceived as proof for the right of the Finnish people to their own sovereign country, language and identity. Lönnrot was a Swedish speaker who saw the need and importance of a shared language for an emerging nation that was not Swedish or Russian, the languages of an oppressor, but Finnish, the language of the people who lived in the Grand Duchy.

The Kalevala was first published in 1835 and a second, reworked edition came out in 1849. The 1849 edition is the version that is still read today. It has 22,795 verses that are divided into several dozen stories. Together these stories create a whole, grand narrative. In the center of the runes are two tribes, the people of Kaleva led by the old, steadfast Väinämöinen, a powerful spiritual leader with the gift of song. In Pohjola, the North, rules a mighty old woman, Louhi, a witch, the ragged toothed hag of the North. Both tribes have fortunes and misfortunes in the stories: they venture out to compete for the hand of beautiful and clever maidens, they fight, they love, they die horrible deaths in the jaws of monsters or at the hands of their foes—just like the fate of heroes in all epic stories. What makes the Kalevala different from other epic stories is the vulnerability of its heroes. Where mighty godlike heroes of other epic stories escape from the flames of dragons and the horrors of cave dwelling creatures, the characters of the Kalevala suffer defeats, cry in pain and loneliness, never win the heart of the person they court, break bonds that were never to be broken and, in the end, there is death, the ultimate departure. The characters have a human tenderness that is rarely found in epic stories with heroes and villains.

Song is central in the Kalevala. We can read lengthy passages about spells Väinämöinen sings when he builds a boat to carry him across the stormy seas to Pohjola, how spells can be used to enchant someone, or which spell to sing in order to retrieve a missing spell from the belly of a forest spirit. Kalevala is full of singing competitions, exchanges of spells between characters—the song is mightier than the sword. The Kalevala is written in a strict tetrameter and is meant to be sung rather than read. An identifiable character of the Kalevala is the use of alliteration: two or more words in a line begin with the same sound. In strong alliteration even the following vowel is the same. Here, an example from the very first lines of the Kalevala:

Mieleni minun tekevi = mastered by desire impulsive

aivoni ajattelevi = by a mighty inward urging

Lähteäni laulamahan = I am ready now for singing

saa’ani sanelemahan = ready to begin the chanting

Poetry as a genre poses challenges to the translator, and the Kalevala’s form makes translation that captures the meter impossible. Despite the intricate nature of the Kalevala, the epic has been translated into numerous languages, including English.

Many artists found inspiration in the Kalevala. For example, Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1861-1935), a Finnish contemporary of Edward Munch (1863-1944), painted large Kalevala themed frescoes for the Finnish pavilion in the Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris. In designing and decorating this entire pavilion dedicated to Finland (a country that did not yet exist), the Finnish cultural elite demonstrated its national spirit. Kalevala themes were central inspirations also for the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius (1865-1957).

But is the Kalevala Finnish? Is it a compilation of authentic Finnish oral poetry, or did Lönnrot in fact appropriate oral tradition he collected on his journeys and simply called it Finnish? The popular use of the book had a great influence on the formation of a positive Finnish identity, and to this day the Kalevala holds a firm position in Finnish culture. Discussing the Kalevala’s origins in the context of collecting oral traditions reveals its historical burden. This is the case for many epic stories and old poetry; the Old Norse and Old Saxon poetic forms can be scrutinized in the same light. Whose poems are these? Who claimed ownership and to what end? The Kalevala can be used as reading material for the pure enjoyment of poetry, but also as a discussion starter about authenticity, oral tradition, and the formation of national identity.

Finnish has about six million speakers worldwide. The Department of Scandinavian regularly offers both Finnish language courses and courses in Finnish Culture and History. Numerous editions of the Kalevala are held by the University Library beginning with an important translation into German from 1852, kept in The Bancroft Library and contemporary with the publication of the later editions of German folklore collected by the Brothers Grimm. Other editions within the Library include a 1965 Finnish text which features Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s paintings, and, beyond English, translations into languages such as French, Yiddish, Hungarian, and Hindi.

Contribution by Lotta Weckström

Lecturer, Department of Scandinavian

Title: Kalevala

Title in English: Kalevala

Author: Lönnrot, Elias, 1802-1884, editor.

Imprint: Helsingissä, 1849.

Edition: 2nd

Language: Finnish

Language Family: Uralic, Finno-Ugric

Source: The HathiTrust Digital Library (Harvard University)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011532640

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Kalevala. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1983.

- Kalevala. Liitteenä kaksikymmentäneljä kuvaa Akseli Gallen-Kallelan maalauksista. Helsinki: Otava, 1965.

- The Kalevala; or, Poems of the Kaleva District. Compiled by Elias Lönnrot. A prose translation with foreword and appendices by Francis Peabody Magoun, Jr. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, 1963.

- Kalevala; a Finn nemzeti hősköltemény. Finn eredetiből fordította: Vikár Béla. Translated into Hungarian. Budapest, Magyar Élet Kiadása, 1943.

- Kalewala, des national-epos der Finnen, nach der zweiten Ausgabe ins deutsche übertragen von Anton Schiefner. Helsingfors: J.C. Frenckell & Sohn, 1852.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Hungarian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Magda Szabó (1917-2007) was a Hungarian novelist, known as the most translated Hungarian author. She worked in multiple genres, including drama, poetry, short stories, and memoirs. For this exhibition, we chose her 1987 novel Az ajtó (“The Door”) for several reasons, first she was repressed as a result of Stalinist excesses. According to a book review of another recently novel only recently translated into English, “her fiction shows the travails of modern Hungarian history from oblique but sharply illuminating angles.”[1] Second, the complex relations between the main characters of Az ajtó: Magda, her husband, and Emerence, the woman helper with an adopted dog, juxtaposed with who is in charge and how the relationship will evolve leads to a creation of a layered narrative. The layered narrative represents a mesmerizing self-weaving quilt of time and contextual protests.[2] As a young poet she won her country’s chief literary honor, the Baumgarten Prize, in 1949. On the same day, the communist regime cancelled this award to a class enemy. She lost her civil- service job, went to teach in a primary school, and only began to publish novels a decade later. Novels such as Az ajtó and Pilátus (“Iza’s Ballad”) are entangled with public upheavals from the repressive governments and Nazi occupation of the 1930s and 1940s, to the sudden annihilation of Hungary’s Jews, and the soul-sapping compromises and betrayals of the Stalinist era.

Called Magyar by its speakers, Hungarian is the language of Hungarians (Magyarok) and is the official language of the Republic of Hungary. It is spoken by over 10 million people in Hungary and also by approximately 3 million ethnic Hungarian minorities in parts of the Czech Republic, Romania, Slovakia, Serbia and other areas bordering Hungary. Hungarian belongs to the Ugric branch of Finno-Ugric languages. Hungarian also has loan words from Germanic, Slavic and Turkic groups of languages. According to Oxford’s International Encyclopedia of Linguistics International Encyclopedia of Linguistics (2nd ed.), Hungarian’s status is described as follows, “Until the end of the 18th century, the status of Hungarian in the juridical, educational, and even literary spheres was at best that of a lesser rival to Latin, and then to German. With the deliberate establishment of the standard literary language, and the prodigious output of the golden age of Hungarian belles-lettres (roughly 1780–1880), dialectal variation was winnowed out. At present, the primary internal variation lies in the contrast of rural vs. urban standard; the latter is roughly equivalent to the speech of Budapest, where one-fifth of the population resides.”[3]

Hungarian was also one of the principle languages of the multiethnic, multilingual Austro-Hungarian Empire since its establishment in 1801. In her essay “The History of the Book in Hungary,” Bridget Guzner notes, “The earliest Hungarian written records are closely linked to Christian culture and the Latin language. The first codices were copied and introduced by travelling monks on their arrival in the country during the 10th century, not long after the Magyar tribes had conquered and settled in the Carpathian Basin. The first incunabula known as Chronica Hungarorum (“Chronicle of Hungarians”) was published in 1473 by András Hess.”[4] According to The Oxford Dictionary of the Renaissance, “Scholarly study of the Hungarian language began in 1539 with the publication of Pannonius’ Grammatica Hungaro-Latina.”[5] Until the end of the 18th century, the principal language of Hungarian literature was Latin, which was the language of the markedly literary court of Matthias Corvinus. The most important writers of Latin in Hungary were János Vitéz, Pannonius (whose poetry included epigrams, panegyrics, and epics), the Italian Antonio Bonfini (who wrote an important history of Hungary, the Rerum Hungaricarum decades IV, Basel, 1568), and the Hungarian Sambucus, who wrote a continuation of Bonfini’s history. In the Hungarian language, the most influential works were a series of translations of the Bible into Hungarian. The first great lyric poet of Hungary was Valentine Bálint Balassi (1554–95).”[6]

At UC Berkeley, Hungarian is currently taught by Eva Szoke in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, but the credit for creation of Hungarian language teaching program on campus can be given to Ms. Agnes Mihalik, who arrived at UC Berkeley in 1982. Outside the Hungarian language program, Professor Jason Wittenberg and Professor-Emeritus Andrew Janos, both from the Department of Political Science, specialize in Central and Eastern Europe with a focus on Hungary.

Contribution by Liladhar Pendse

Librarian for East European and Central Asian Studies, Doe Library

Source consulted:

- “After 50 years, a Hungarian novel is published in English,” The Economist (February 28, 2019, (accessed 6/12/20)

- “The Hungarian Despair of Magda Szabó’s ‘The Door’,” by Cynthia Zarin. The New Yorker (April 29, 2016) (accessed 6/12/20)

- International Encyclopedia of Linguistics. 2nd ed. William J. Frawley, ed. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. (accessed 6/12/20)

- “The History of the Book in Hungary” by Bridget Guzner in The Oxford Companion to the Book. Michael F. Suarez and H.R. Woudhuysen, ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. (accessed 6/12/20)

- The Oxford Dictionary of the Renaissance. Gordon Campbell, ed. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. (accessed 6/12/20)

- Ibid.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Az ajtó

Title in English: The Door

Author: Szabó, Magda, 1917-2007

Imprint: Budapest: Magvető, 1987.

Edition: 1st

Language: Hungarian

Language Family: Uralic, Finno-Ugric

Source: Digitális Irodalmi Akadémia

URL: https://reader.dia.hu/document/Szabo_Magda-Az_ajto-889

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Az ajtó. Budapest: Magvető, 1987.

- The Door. Translated from the Hungarian by Len Rix; Introduction by Ali Smith. New York, NY: New York Review Books, 2015.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Ancient Greek

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

“Sing to me of the man, Muse, the man of twists and turns driven time and again off course, once he had plundered the hallowed heights of Troy.” So begins the epic tale of Odysseus, “the man of twists and turns” and king of Ithaca who, after he and his fellow Greeks achieved victory over the kingdom of Troy (a campaign recounted in the Iliad), sets off on his return voyage told in the Odyssey (“Ὀδύσσεια”).[1] That trip, which should have taken no more than a few weeks, becomes instead a journey of ten years as Odysseus and his men are confronted by storms, creatures of all kinds, and interventions by the gods.

The fate of Odysseus’ household on the island of Ithaca, located off the western coast of Greece, is the focus of the first part of the Odyssey. In the absence of Odysseus, his house has fallen under assault by a gluttonous group of men, the “suitors”, who rival one another for the hand of his faithful wife, Penelope, as they linger day after day, taking advantage of the family’s hospitality. His son, Telemachus, on the cusp of manhood, sets out for news of Odysseus, but returns home without certain information while the suitors plot his murder.

Well into the text, Odysseus describes the circumstances of his much delayed return. Sailing homeward from Troy, the 12 ships bearing Odysseus and his countrymen are hurled off course by a storm and a series of fantastic events begins. They survive the land of the Lotus-eaters, where they nearly succumb to forgetfulness after consuming the potent lotus plant, and then land on the island of the one-eyed Cyclopes. One Cyclops, Polyphemus, begins to devour Odysseus’ companions before the cunning Odysseus and his men take up a fiery stake and put out the creature’s single eye, escaping to their ship, and earning the wrath of Polyphemus’ father, the god Poseidon. Blown off course again, the group is attacked by the Laestrygonians, boulder-throwing giants, who destroy all of the ships but that of Odysseus and consume their crews. Odysseus’ ship next lands on the island of Circe, a sorceress who transforms Odysseus’ comrades into swine, brings Odysseus to her bed, and keeps him with her for a year. Following Circe’s release of Odysseus and his men, Odysseus makes a brief descent into the underworld, where he encounters a variety of dead including comrades who fought in the Trojan War, Heracles, his own mother, and the prophet Tiresias, who foretells his journey home. Returning to the surface and sailing onward, Odysseus has his men tie him to the ship’s mast while they plug their ears to avoid the tempting and deadly cry of the Sirens. After further events that result in the destruction of his ship and his remaining men, Odysseus reaches the island of the nymph Calypso, who holds him there as her lover for seven years.

Finally, Odysseus returns to Ithaca, where he had last stepped foot 20 years before. Observing the behavior of the suitors firsthand while disguised as a beggar, he crafts a plan: He blocks the doors of the hall, and with his son Telemachus at his side, assails the suitors with arrows and runs them through with spears while the goddess Athena protects him from the suitors’ weapons. Having slaughtered the abusive lot, Odysseus and Penelope are at last reunited.

According to ancient tradition, the Iliad and the Odyssey were both the poetic creations of a blind poet named Homer. Although Homer may be a fictitious person, these epic poems, or parts of them, must have been sung for some time by actual poets who knew them from memory at a time when writing was non-existent in Greece. Probably in the 8th century BC, the poems were written down for the first time following the Greeks’ borrowing of the Phoenician alphabet. The Iliad and the Odyssey were read throughout antiquity, and further served as a major point of reference for Greek works across genres, and, in Latin, most importantly provided a source of inspiration for the creation of the Aeneid, the epic foundation story of the founding of Rome which the poet Virgil composed in the 1st century BC.

Along with other myths, many scenes from the Homeric epics were taken up within ancient visual culture. One of the earliest examples is the blinding of Polyphemus, painted in the 7th century BC on the well-known Eleusis Amphora, which was used as the container for a child’s burial. Much later, together with many other aspects of culture which the Romans adopted from the Greeks, the Odyssey became represented in Roman art. The finest examples include the 1st century BC Odyssey Landscapes which decorated a luxurious house in Rome, and the 1st century AD sculpture groups within a grotto at the villa of the emperor Tiberius at Sperlonga, on the coast between Rome and Naples.

The Odyssey was copied and recopied through handwritten manuscripts in the Middle Ages, and in 1488 the first print edition was produced in Florence. As one of the classic texts of European, and indeed world literature, innumerable editions in Greek and in translation have been published since then. In the 20th century and beyond, the story of Odysseus has continued to influence literary and popular culture, from James Joyce’s 1922 Ulysses (the Latinized form of “Odysseus”) to the 2000 film O Brother, Where Out Thou, in which George Clooney plays “Ulysses Everett McGill”. The themes of the Odyssey are enduring: U.S. military veterans returning from recent wars in the Middle East have read the Iliad and the Odyssey within discussion groups and found parallels between their experiences and that of the war veteran Odysseus.[2] In 2018, readers from around the globe voted the Odyssey to the top of the list in the BBC poll, “100 Stories that Shaped the World”.[3]

UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library possesses an excellent selection of early editions of the Odyssey beginning with an example printed in Venice by Aldus Manutius in 1504. In addition, seven Egyptian papyri from the 2nd century BC to the 2nd century AD in The Bancroft Library’s Center for the Tebtunis Papyri preserve handwritten fragments or quotations from the Odyssey in Ancient Greek. One, for example, from the late 1st or early 2nd century AD and recovered from a house at Tebtunis, contains a fragment from Book 11 of the Odyssey which describes Odysseus’ journey to the underworld. Aside from modern editions in Ancient Greek, the University Library owns numerous translations in English and a wide variety of other languages such as Italian, Icelandic, Russian, Turkish, and Hebrew.

Ancient Greek, along with Latin, have been offered at UC Berkeley since the university’s founding in 1868, and originally constituted required subjects for the BA degree. Greek emerged as its own department when a departmental structure was established in 1896, eventually joining the department of Latin to form a new Classics department in 1937. Today, Homer is taught regularly within the Classics department in both Ancient Greek and in translation.[4]

Contribution by Jeremy Ott

Classics and Germanic Studies Librarian, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Homer. The Odyssey. Translated by Robert Fagles. New York: Penguin, 1996. Book One, lines 1-3.

- Ring, Wison. “‘Homer Can Help You’: War Veterans Use Ancient Epics to Cope,” AP News (March 13, 2018) (accessed 6/8/20)

- Haynes, Natalie . “The Greatest Tale Ever Told?,” BBC News (

- UC Berkeley Department of Classics – History, https://classics.berkeley.edu/about/department-history

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Ὀδύσσεια

Title in English: Odyssey

Author: Homer

Imprint: Venitiis : [Publisher not identified], secundo cale[n]das nouem, 1504.

Edition: 1st

Language: Ancient Greek

Language Family: Indo-European, Greek

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (Northwestern University)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/102392919

Other Online Resources:

Digitized Papyri in the Center for the Tebtunis Papyri containing fragments or quotations of the Odyssey:

- P.Tebt.0270. Possibly a fragment of a grammar; lines 2-6 contain a quotation from the Odyssey, book 18, line 130.

- P.Tebt.0271 Recto. Fragment of Hesiod’s Catalog of women (the Tyro passage); lines 2-3 are identical to Homer’s Odyssey, Book 2, lines 249-250.

- P.Tebt.0696. Fragments from the Odyssey, Book 1.

- P.Tebt.0431. Fragments of the Odyssey, Book 11.

- P.Tebt.Suppl.01,032-01,033. Fragments of the Odyssey, Book 12.

- P.Tebt.0432. Fragment from the Odyssey, Book 24.

- P.Tebt.0697. Lines from Books 4 and 5 of the Odyssey.

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Homērou Ilias = Homeri Ilias. Venice: Aldus, 1504.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

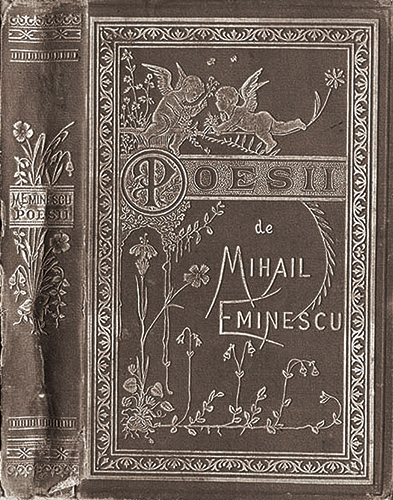

Romanian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Mihail Eminescu, pseudonym of Mihail Eminovici, (1850-1889), was a poet who transformed both the form and content of Romanian poetry, creating a school of poetry that strongly influenced Romanian writers and poets in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Eminescu was educated in the Germano-Romanian cultural centre of Cernăuţi (now Chernovtsy, Ukraine) and at the universities of Vienna and Berlin, where he was influenced by German philosophy and Western literature. In 1874, he was appointed school inspector and librarian at the University of Iaşi but soon resigned to take up the post of editor in chief of the conservative paper Timpul. His literary activity came to an end in 1883, when he suffered the onset of a mental disorder that led to his death in an asylum.

Eminescu’s talent was first revealed in 1870 by two poems published in Convorbiri literare, the organ of the Junimea society in Iaşi. Other poems followed, and he became recognized as the foremost modern Romanian poet. Mystically inclined and of a melancholy disposition, he lived in the glory of the Romanian medieval past and in folklore, on which he based one of his outstanding poems, “Luceafărul” (1883; “The Evening Star”). Eminescu’s poetry has a distinctive simplicity of language, a masterly handling of rhyme and verse form, a profundity of thought, and a plasticity of expression which affected nearly every Romanian writer of his own period and after. His poems have been translated into several languages, including an English translation in 1930, but chiefly into German. Among his prose writings, apart from many studies and essays, the best-known are the stories “Cezara” and “Sărmanul Dionis” (1872).[1]

Romanian, or Rumanian, is one of the Romance languages that is spoken in Eastern Europe, principally in Romania and the Republic of Moldova. It evolved in very different circumstances from its western sister languages such as Spanish and Italian, and was profoundly affected by the Orthodox Church, the Greek and Slavonic languages, and the Ottoman Empire. It has a lexical affinity with Old Church Slavonic.[2] For the latter half of the 20th century, UC Berkeley had a very active program in Romanian. The Russian-born Romance etymologist and philologist Yakov Malkiel, who taught at Berkeley for over 55 years, mentored students who specialized in Romanian linguistics. In 1947, he became founding editor of the prestigious journal Romance Philology which is still published today. ProQuest’s Dissertation & Theses lists more than 227 doctoral dissertations from UC Berkeley that are related in one way or another to Romania and the Romanian language.[3] However in light of funding cuts, Romanian has not been taught at Berkeley in over two years. Graduate students in the interdisciplinary Romance Languages and Literatures (RLL) program may choose Romanian as one of their languages.[4]

Contribution by Liladhar Pendse

Librarian for East European and Central Asian Studies, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- “Mihail Eminescu: Romanian Poet” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. (accessed 5/1/20)

- Price, Glanville. Encyclopedia of the Languages of Europe. Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 1998.

- Proquest Dissertations & Theses (accessed 5/1/20)

- Romance Languages and Literatures, UC Berkeley (accessed 5/1/20)

- Cimpoi, Mihai (coord.), 2020, Eminescu—Opere (vol. I-VIII), Editura Gunivas.On the matter of the assassination and those involved:

- Lepuş, Miruna, 2021, Dosarele de interdicţie ale lui Mihai Eminescu, Editura Cartex.

- Barbu, Constantin, 2008, Codul invers, Editura Sitech.

- Georgescu, Nicolae, 2014, Boala şi moartea lui Eminescu, Editura Floare Albastră.

- Georgescu, Nicolae, 2011, Eminescu: ultima zi la Timpul, Editura ASE.

- Vuia, Ovidiu, 1997, Despre boala şi moartea lui Mihai Eminescu—studiu patografic, Editura Făt-Frumos.

On the matter of the birthdate:

- Marin, I.D., 1979, Eminescu la Ipoteşti, Editura Junimea.

- Ştefanelli, Teodor V., 1983, Amintiri despre Eminescu, Editura Junimea.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Poezii complecte

Title in English: Complete Poems

Author: Eminescu, Mihai, 1850-1889.

Imprint: Iași, Editura librărieĭ frațiĭ Șaraga [188-?].

Edition: n/a

Language: Romanian

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (Harvard University)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100545314

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Poezii / M. Eminescu ; antologie, prefață și tabel cronologic de George Gană ; ilustrați de Dumitru Verdeș. București : Editura Minerva, 1999.

- Poezii / M. Eminescu ; ediție critică de D. Murărașu. București : Editura Minerva, 1982. v.1-3

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

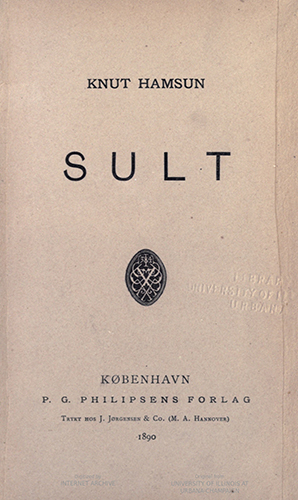

Norwegian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Det var i den Tid, jeg gik omkring og sulted i Kristiania, denne forunderlige By, som ingen forlader, før han har faaet Mærker af den . . .

It was in those days when I wandered about hungry in Kristiania, that strange city which no one leaves before it has set its mark upon him . . .

(trans. Sverre Lyngstad, 1996)

So opens Knut Hamsun’s novel, Sult (Hunger). When Sult was published in 1890, it represented a literary breakthrough not just in Scandinavia but also throughout Europe. Though Hamsun’s later novels would take more conventional forms, Sult was a harbinger of 20th century modernism for its stream-of-consciousness narration and its focalization of a vagabond figure who struggles to cope with modern urban life. The novel’s plot is spare: an unnamed—and unreliable—narrator arrives in Kristiania (now Oslo); he struggles to get work as a writer and has occasional run-ins with strangers; three months later, he leaves the city by boat. What makes the novel remarkable is how it portrays the inner life of a—literally—starving artist. Through the narrator’s increasingly wild musings, it is difficult for the reader to decipher whether the protagonist is insane or just hungry, and whether his hunger is forced upon him by poverty or voluntarily undertaken as part of a fascinating, yet ambiguous, creative project. As Hamsun put it elsewhere, Sult aims to reveal “the unconscious life of the soul.”[1]

Knut Hamsun is widely accepted as one of Norway’s greatest authors. He is second only to Henrik Ibsen in terms of international renown and he won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1920 for his novel Markens grøde (“Growth of the Soil”). However, his legacy has been hotly debated, and his reputation severely damaged, by his strong Nazi sympathies and support of the Nazi occupation of Norway (1940-45).

Though Sult was written in Norwegian, it is a Norwegian highly inflected by Danish spelling. For 400 years, Norway was under Danish rule, during which time Danish was the language of writing and instruction in Norway. After declaring independence from Denmark in 1814, Norwegians were eager to establish an official language that better reflected the range of Norwegian dialects, but this has proven to be a long and contentious process. When Sult was published, Norway still had a shared publishing culture with Denmark, and, indeed, the first edition of Sult was published in Copenhagen.

Hunger has been taught in various courses at UC Berkeley in the Department of Scandinavian, including undergraduate courses on “place in literature” and “consciousness in the modernist novel,” as well as in graduate courses on affect and fictionality. The department, which is one of only three independent Scandinavian departments in the United States, also offers courses in beginning and intermediate Norwegian, a language spoken by more than 5 million people. In addition to the 1890 first edition of Sult, the UC Berkeley Library owns multiple English translations of this landmark work.

Contribution by Ida Moen Johnson,

PhD Student in the Department of Scandinavian

Notes:

- This phrase comes from the title of Hamsun’s 1890 essay, “Fra det ubevidste Sjæleliv.”

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Sult

Title in English: Hunger

Author: Hamsun, Knut, 1859-1952

Imprint: Copenhagen: P.G. Philipsens Forlag, 1890.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Norwegian

Language Family: Indo-European,

Source: The Internet Archive (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)

URL: https://archive.org/details/sult00hams/page/n5/mode/2up

Other online editions:

- Hunger. Translated from the Norwegian of Knut Hamsun by George Egerton, with an introduction by Edwin Björkman. New York: A.A. Knopf, 1935, ©1920. HathiTrust

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Sult. København, P.G. Philipsen Forlag, 1890.

- Hunger. Translated into English by Sverre Lyngstad. New York: Penguin Books, 1998.

- Hunger. Introduction by Paul Auster; translated from the Norwegian and with an afterword by Robert Bly. New York: Noonday Press, 1998.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

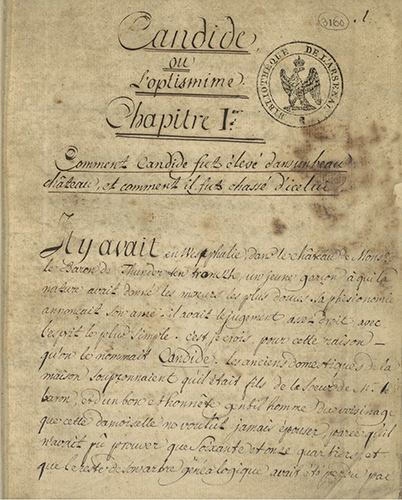

French

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Si c’est ici le meilleur des mondes possibles, que sont donc les autres?

If this is the best of all possible worlds, what are the others like?

— Voltaire, Candide, ou, l’Optimisme (trans. Burton Raffel)

Voltaire, né François-Marie Arouet (1694-1778), was a French philosopher who mobilized the power of Enlightenment principles in 18th-century Europe more than any other thinker of his day. Born into a prosperous bourgeois Parisian family, his father steered him toward law, but he was intent on a literary career. His tragedy Oedipe, which premiered at the Comédie Française in 1718, brought him instant financial and social success. A libertine and a polemicist, he was also an outspoken advocate for religious tolerance, pluralism and freedom of speech, publishing more than 2,000 works in all possible genres during his lifetime. For his bluntness, he was locked up in the Bastille twice and exiled from Paris three times.[1] Fleeing royal censors, Voltaire fled to London in 1727 where he, despite arriving penniless, spent two and a half years hobnobbing with nobility as well as writers such as Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift.[2]

After his sojourn in Great Britain, he returned to the Continent and lived in numerous cities (Champagne, Versaille, Amsterdam, Potsdam, Berlin, etc.) before settling outside of Geneva in 1755 shortly after Louis XV banned him from Paris. “It was in his old age, during the 1760s and 1770s,” writes historian Robert Darnton, “that he wielded his second and most powerful weapon, moral passion.”[3] Early in 1759, Voltaire completed and published the satirical novella Candide, ou l’Optimisme (“Candide, or Optimism”) featured in this entry. In 1762, he published Traité sur la tolerance (“Treatise on Tolerance”), which is considered one of the greatest defenses of religious freedom and human rights ever composed. Soon after its publication, the American and French Revolutions began dismantling the social world of aristocrats and kings that we now refer to as the Ancien Régime.[4]

With Candide in particular, Voltaire is credited with pioneering what is called the conte philosophique, or philosophical tale. Knowing it would scandalize, the story was published anonymously in Geneva, Paris and Amsterdam simultaneously and disguised as a French translation by a fictitious Mr. Le Docteur Ralph. The novella was immediately condemned for its blasphemy and subversion, yet within weeks sold 6,000 copies within Paris alone.[5] Royal censors were unable to keep up with the proliferation of illegal reprints, and it quickly became a bestseller throughout Europe.

Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726) is considered one of its clearest precursors in both form and parody. Candide is the name of the naive hero who is tutored by the optimistic philosophy of Pangloss, who claims that “all is for the best in this best of all possible worlds” only to be expulsed in the first few pages from the opulent chateau in which he grew up. The story unfolds as Candide travels the world and encounters unimaginable human suffering and catastrophes. Voltaire’s satirical critique takes aim at religion, authority, and the prevailing philosophy of the time, Leibnizian optimism.

While the classical language of Candide is more than 260 years old, it is easy enough to comprehend today. As the lingua franca across the Continent, French was accessible to a vast French-reading public since gathering strength as a literary language since the 16th century.[6] However, no language stays the same forever and French is no exception. Old French, which is studied by medievalists at Berkeley, covers the period up to 1300. Middle French spans the 14th and 14th centuries and part of the early Renaissance when the study of French language was taken more seriously. Modern French emerged from one of the two major dialects known as langue d’oïl in the middle of the 17th century when efforts to standardize the language were taking shape. It was then that the Académie Française was established in 1635.[7] One of its members, Claude Favre de Vaugelas, published in 1647 the influential volume, Remarques sur la langue françoise, a series of commentaries on points of pronunciation, orthography, vocabulary and syntax.[8]

At UC Berkeley, scholars have been analyzing Candide and other French texts in the original since the university’s founding. The Department of French may have the largest concentration of French speakers on campus, and French remains like German, Spanish, and English one of the principal languages of scholarship in many disciplines. Demand for French publications is great from departments and programs such as African Studies, Anthropology, Art History, Comparative Literature, History, Linguistics, Middle Eastern Studies, Music, Near Eastern Studies, Philosophy, and Political Science. The French collection is also vital to interdisciplinary Designated Emphasis PhD programs in Critical Theory, Film & Media Studies, Folklore, Gender & Women’s Studies, Medieval Studies, and Renaissance & Early Modern Studies.

UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library is home to the most precious French holdings, including medieval manuscripts such as La chanson de geste de Garin le Loherain (13th c.) and dozens of incunables. More than 90 original first editions by Voltaire can be located in these special collections, including La Henriade (1728), Mémoires secrets pour servir à l’histoire de Perse (1745) Maupertuisiana (1753), L’enfant prodigue: comédie en vers dissillabes (1753) and a Dutch printing of Candide, ou, l’Optimisme (1759). Other noteworthy material from the 18th century overlapping with Voltaire include the Swiss Enlightenment and the French Revolutionary Pamphlet collections.

Contribution by Claude Potts

Librarian for Romance Language Collections, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Davidson, Ian. Voltaire. New York: Pegasus Books, 2010. xviii

- Ibid.

- Darnton, Robert. “To Deal With Trump, Look to Voltaire,” New York Times (Dec. 27, 2018).

- Voltaire. Candide or Optimism. Translated by Burton Raffel. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

- Davidson, 291.

- Levi, Anthony. Guide to French Literature. Chicago: St. James Press, c1992-c1994.

- Kors, Alan Charles, ed. Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment. Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Ibid.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Candide, ou L’optimisme (Manuscrit La Vallière)

Title in English: Candide, ou L’optimisme (La Vallière Manuscript)

Author: Voltaire, 1694-1778

Imprint: La Vallière (Louis-César, duc de). Ancien possesseur, 1758.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: French

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Gallica (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, 3160)

URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b520001724

Other online editions:

- Candide, ou l’Optimisme , traduit de l’allemand de M. le docteur Ralph. Paris: Lambert, 1759. (Gallica)

- Candide, ou l’Optimisme. Première Partie 1. Édition revue, corrigée et augmentée par l’auteur. Aux Delices, 1763.(Gallica)

- Candide, ou l’Optimisme, traduit de l’allemand de M. le docteur Ralph. Seconde partie. Aux Delices, 1761. (Gallica)

- Candide ou L’optimisme. Préface de Francisque Sarcey; illustrations de Adrien Moreau. Paris: G. Boudet, 1893. (Gallica)

- Candide, ou, L’optimisme. Illustré de trente-six compositions dessinées et gravées sur bois par Gérard Cochet. Paris: Les Editions G. Crès et Cie, 1921. (HathiTrust)

- Candide, or Optimism. Translated into English by Burton Raffel. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005. (ebrary-UCB access only)

- Candide / Voltaire. [United States]: Tantor Audio: Made available through hoopla, 2006. ebook and audiobook (OverDrive-UCB access only)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Candide, ou, l’Optimisme / traduit de l’allemand de Mr. le docteur Ralph. Amsterdam: Marc-Michel Rey, MDCCLIX [1759].

- Candide, ou, L’optimisme. Édition présentée, établie et annotée par Frédéric Deloffre. Paris: Gallimard, 2003.

- Candide. [Graphic novel] Interventions graphiques de Joann Sfar. Rosny: Éditions Bréal, 2003.

- Candide, or Optimism. Translated and edited by Theo Cuffe with an introduction by Michael Wood. New York : Penguin Books, 2005.

- Candide, ou L’optimiste. [Graphic novel] Scénario, Gorian Delpâture & Michel Dufranne; dessin, Vujadin Radovanovic; couleur, Christophe Araldi & Xavier Basset. Paris: Delcourt, 2013.

- Candide or, Optimism: The Robert M. Adams Translation, Backgrounds, Criticism. Edited by Nicholas Cronk. New York : W. W. Norton & Company, 2016.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

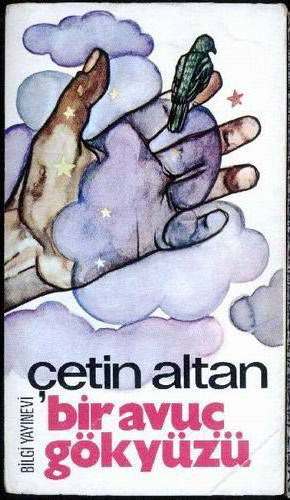

Turkish

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

The Turkish writer Çetin Altan (1927-2015) was a politician, author, journalist, columnist, playwright, and poet. From 1965 to 1969, he was deputy for the left-wing Workers Party of Turkey—the first socialist party in the country to gain representation in the national parliament. He was sentenced to prison several times on charges of spreading communist propaganda through his articles. He wrote numerous columns, plays, works of fiction (including science fiction), political studies, historical studies, essays, satire, travel books, memoirs, anthologies, and biographical stories.[1]

His novel Bir Avuç Gökyüzü (A Handful of Sky), was published in 1974 and takes place in Istanbul. A 41-year-old politically indicted married man spends two years in prison and then is released. Several months later he is called into the police station where the deputy commissioner has him sign a notification from the public prosecutor’s office. This time, the man will serve three more years and he has a week to surrender to the courthouse. The novel chronicles the week of this man’s life before he serves his extended sentence. Suddenly, an old classmate with thick-rimmed glasses appears with the pretense to help. The classmate convinces the main character to petition his sentence and have it postponed for four months so that he can make the necessary arrangements to support his family. Unsurprisingly, the petition is rejected on the grounds of the severity of the purported offense that led to conviction. His classmate then urges the protagonist to take a freighter and flee the country, but instead he turns himself in. From the prison ward’s iron-barred windows he can only see a handful of sky.[2] The protagonist experiences lovemaking with his mistress mainly as a metaphor for freedom lost; the awkward and clumsy sex he has with his wife, on the other hand, seems an apt metaphor for the emotionally inert life he leads both in and outside of prison.[3]

Çetin Altan was well aware of language’s power and wrote articles on the Turkish language in the newspapers where he was employed as a journalist. At the age of 82 and during his acceptance speech at the Presidential Culture and Arts Grand Awards in 2009, Mr. Altan said, “İnsan kendi dilinin lezzetini sevdiği kadar vatanını sever’’ (A person loves the homeland as much as he loves the flavor of his own language). He loved Turkish and wrote with that love. In his works, as he put it, he “never betrayed the language and the writing.”[4]

An argument can easily be made to study Turkish. There are 80 million people who speak Turkish as their first language, making it one of the world’s 15 most widely spoken first languages. Another 15 million people speak Turkish as a second language. For example there are over 116,000 Turkish speakers in the United States, and Turkish is the second most widely spoken language in Germany. Studying Turkish also lays a solid foundation for learning other modern Turkic languages, like Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Tatar, Uzbek, and Uighur. The different Turkic languages are closely related and some of them are even mutually intelligible. Many of these languages are spoken in regions of vital strategic importance, like the Caucasus, the Balkans, China, and the former Soviet Union. Mastery of Turkish grammar makes learning other Turkic languages exponentially easier.[5]

Turkish is not related to other major European or Middle Eastern languages but rather distantly related to Finnish and Hungarian. Turkish is an agglutinative language, which means suffixes can be added to a root-word so that a single word can convey what a complete sentence does in English. For example, the English sentence “We are not coming” is a single word in Turkish: “come” is the root word, and elements meaning “not,” “-ing,” “we,” and “are” are all suffixed to it: gelmiyoruz. The regularity and predictability in Turkish of how these suffixes are added make agglutination much easier to internalize.[5] [6] At UC Berkeley, modern Turkish language courses are offered through Department of Near Eastern Studies.[7]

When I was asked to write a short essay about the Turkish language based on a book, I was pleasantly surprised to discover that the UC Berkeley Library has many of Çetin Altan’s books in their original language. While he was my favorite author when I was in high school and in college in Turkey during the 1970s and 1980s, my move to the United States and life in general caused these memories to fade away. Now I am excited and feel privileged with the prospect of reading his books in Turkish again and rediscovering them after all these years.

Contribution by Neil Gali

Administrative Associate, Center for Middle Eastern Studies

Sources consulted:

- http://www.turkishculture.org/whoiswho/memorial/cetin-altan-953.htm (accessed 3/10/20)

- https://www.evvelcevap.com/bir-avuc-gokyuzu-kitap-ozeti (accessed 3/10/20)

- “İnsan kendi dilinin lezzetini sevdiği kadar vatanı sever,” (October 21, 2017) P24: Ağimsiz Gazetecilik Platformu = Platform for Independent Journalism. http://platform24.org/p24blog/yazi/2492/-insan-kendi-dilinin-lezzetini-sevdigi-kadar-vatani-sever (accessed 3/10/20)

- İrvin Cemil Schick, “Representation of Gender and Sexuality in Ottoman and Turkish Erotic Literature,” The Turkish Studies Association Journal, Vol. 28, No. 1/2 (2004), pp. 81-103, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43383697 (accessed 3/10/20)

- https://names.mongabay.com/languages/Turkish.html (accessed 3/10/20)

- https://www.bu.edu/wll/home/why-study-turkish (accessed 3/10/20)

- http://guide.berkeley.edu/courses/turkish (accessed 3/10/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Bir Avuç Gökyüzü

Title in English: A Handful of Heaven

Author: Altan, Çetin, 1927-2015

Imprint: Kavaklıdere, Ankara : Bilgi Yayınevi, 1974.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Turkish

Language Family: Turkish, Turkic

Recommended Online Resource:

“İnsan kendi dilinin lezzetini sevdiği kadar vatanı sever,” (October 21, 2017) P24: Ağimsiz Gazetecilik Platformu = Platform for Independent Journalism. Blog post of tribute to the writer with photos, videos, etc.

http://platform24.org/p24blog/yazi/2492/-insan-kendi-dilinin-lezzetini-sevdigi-kadar-vatani-sever (accessed 3/10/20)

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Breton

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

“Lec’h ma vije ‘r zorserienn hag ar zorserezed;

Hag a diskas d’in ‘r secret ewit gwalla ann ed.”

“Where were the wizards and witches,

for they are are the ones who taught me how to spoil the wheat.”

from “Janedik ar zorseres” in Gwerziou Breiz-Izel: Chants populaires de la Basse-Bretagne

François-Marie Luzel (1821-1895) was a French folklorist and Breton-language poet who assumed a rigorous approach to documenting the Breton oral tradition. After publishing a book which included some of his own poetry in 1865 entitled Bepred Breizad (Always Breton), he published a selection of the texts that he collected in the two-volume set Chants et chansons populaires de la Basse-Bretagne (Melodies and Songs from Low-Brittany) in 1868. It is this latter work that is featured here and offers a parallel translation in French with the intent of making the corpus of songs available to as wide a readership as possible. Throughout the 19th century, Celtic revivalists such as the controversial Théodore Hersart de la Villemarqué undertook an equally ambitious project to collect, preserve, and disseminate folk songs and stories. According to Stephen May, “The modern Breton nationalist movement draws heavily on the persistence of Breton traditions, myths memories and symbols (including language) which have survived in various forms, throughout the period of French domination since 1532.”[1]

Of the many minority languages spoken in France today, Breton (Brezhoneg) is the only one of the Celtic branch of the Indo-European family. Its history can be traced to the Brythonic or Brittonic language community that once extended from Great Britain to Armorica (present-day Brittany) and as far as northwestern Spain beginning in the 9th century. It was the language of the upper classes until the 12th century, after which it became the language of commoners in Lower Brittany as the nobility adopted French. Because of the predilection for French and Latin in the early modern and modern periods, there exists a limited tradition of Breton literature. After the revolution of 1789 when French became the official language, regional languages and dialects became viewed as anti-democratic and hence prohibited in commercial and workplace communications. The Loi Deixonne of 1951 opened the doors grudgingly for the teaching of Breton in France together with Basque, Catalan and Occitan. There has since been some expansion to roughly 5% of the school population.[2] Despite a flowering of literary production since the 1940s, Breton has been classified as “severely endangered” with approximately 250,000 native speakers.[3] Since 1911, Breton has been a core language taught in UC Berkeley’s Celtic Studies program, the oldest of its kind in the country.[4]

Contribution by Claude Potts

Librarian for Romance Language Collections, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- May, Stephen. Language and Minority Rights: Ethnicity, Nationalism and the Politics of Language. 2nd New York: Routledge, 2012.

- Price, Glanville. Encyclopedia of the Languages of Europe. Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 1998.

- UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, http://www.unesco.org/languages-atlas.

- History of Celtic Studies at UC Berkeley, http://celtic.berkeley.edu/celtic-studies-at-berkeley

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Gwerziou Breiz-Izel: Chants populaires de la Basse-Bretagne, recueillis et traduits par F.M. Luzel

Title in English: Gwerziou Breiz-Izel: Melodies and Songs from Low-Brittany

Author: Luzel, François-Marie, 1821-1895.

Imprint: Lorient, É. Corfmat; [etc., etc.] 1868-74.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Breton

Language Family: Indo-European, Celtic

Source: Université de Rennes 2

URL: http://bibnum.univ-rennes2.fr/items/show/321

Other online editions:

- HathiTrust Digital Library: Luzel, François-Marie, 1821-1895. Gwerziou Breiz-Izel: Chants populaires de la Basse-Bretagne. vols. 1-2. Lorient: É. Corfmat; [etc., etc.], 1868-74.

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Luzel, François-Marie, 1821-1895. Gwerziou Breiz-Izel: Chants populaires de la Basse-Bretagne. vols. 1-2. Lorient: É. Corfmat; [etc., etc.], 1868-74.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)