Tag: women’s history month

A Californiana Returns to the Bay Area: Ana María de la Guerra de Robinson

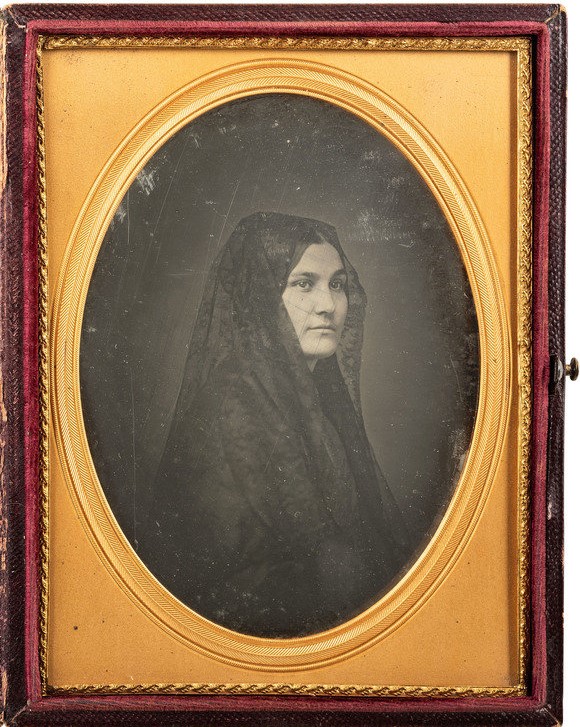

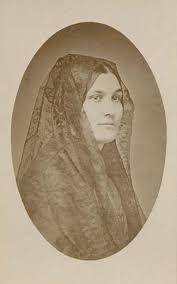

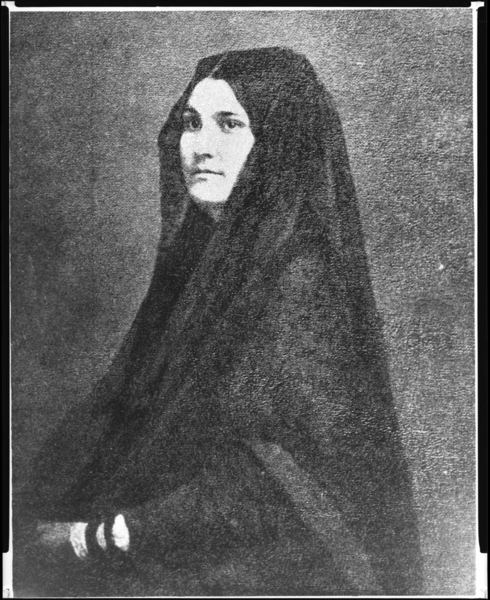

Women’s history month is the perfect time to announce an exciting addition to Bancroft Library’s collection of daguerreotype portraits. At the end of 2023 the library was able to acquire a beautiful 1850s portrait of a Californiana: doña Ana María de la Guerra de Robinson, also known as Anita.

In this large (half plate format) daguerreotype of about 1850-1855, Anita wears a lace mantilla, in the Spanish fashion. A beautiful large daguerreotype like this was an extravagance at the time, and the portrait is all the more evocative because Anita, tragically, died within a few years of its creation.

Fortunately, quite a bit is known about her life. Anita was born into the prominent de la Guerra family of Santa Barbara in 1821 -– the same year the Spanish colonial period ended and control by an independent Mexico began. She was married at age 14, to an American trader and businessman named Alfred Robinson, 14 years her senior. This wedding is described in Richard Henry Dana’s Two Years Before the Mast, so we have an unusually detailed account of what was a grand occasion.

She and her husband snuck away from her family in 1838, leaving their baby daughter behind with her grandparents. Anita, age 15, wrote ”We have left the house like criminals and left here those who have possession of our hearts.” Various writers have interpreted these circumstances differently but, whatever the reason for this strange departure, Anita spent the next 15 years in Boston and the East Coast, seemingly eager to return home, but continually disappointed in the hope. It is hard to imagine that her life was entirely happy, in spite of the steady growth of her family and the prosperity and social prominence the Robinsons and de la Guerras enjoyed.

Having borne seven children, and having witnessed from afar (and apparently mourned) the transition of her homeland from Mexican territory to American statehood, Anita finally returned to California in the summer of 1852. It is likely she had her daguerreotype portrait taken at this time, in San Francisco, although it could have been taken back east. Sadly, she lived just three more years in California, dying in Los Angeles in November 1855, a few weeks after giving birth to a son. She is buried at Mission Santa Barbara.

A study of Anita’s life was published by Michele Brewster in the Southern California Quarterly in 2020 (v.102 no. 2, pg. 101-42) . Read more of her story!

With such a fascinating and relatively well-documented life, we’re thrilled to have Anita’s beautiful portrait here at Bancroft. It joins other de la Guerra family portraits, as well as numerous papers related to the family, including “Documentos para la historia de California” (BANC MSS C-B 59-65) by her father, José de la Guerra y Noriega.

Two of Anita’s sisters had “testimonias” recorded by H.H. Bancroft and his staff; one from Doña Teresa de la Guerra de Hartnell (BANC MSS C-E 67) and another from Angustias de la Guerra de Ord (BANC MSS C-D 134).

Anita’s daguerreotype itself presents an interesting conundrum and history. The photographer is unknown, as is common with daguerreotypes. The portrait has been known over the years because later copies exist in several historical collections, including the California Historical Society, the Massachusetts Historical Society, and Bancroft Library’s own Portrait File.

The daguerreotype acquired last Fall was owned for some decades by a collector. When he acquired it, it was unidentified. Later he encountered a reproduction of it in a historical publication, and thus had the identification of the sitter. Each of the known copies is somewhat different from the others. In her article, Brewster reproduces the copy from the Massachusetts Historical Society. It is a paper print on a carte de visite mount bearing the imprint of San Francisco photographer William Shew, at 115 Kearny Street.

Based on this information, Brewster attributed the portrait to Shew; however, Shew is merely the copy photographer. A daguerreotype, largely out of use by the 1860s, is a unique original, not printed from a negative, so only one exists unless it is copied by camera. The carte de visite format was not in widespread use until the 1860s, and Shew was not at the Kearny address until the 1872-1879 period. So the photographer remains unidentified.

Another puzzle is posed by the early 20th century reproductions in the Bancroft Portrait File and the California Historical Society, which appear identical. These copies present a less closely cropped pose than the original daguerreotype, which is perplexing! Anita’s lap and hands are visible in the copies, but not in the daguerreotype. Although the bottom of the daguerreotype plate is obscured by its brass mat, there is not enough room at the lower edge to include these details.

How could a copy contain more image area than the original? Upon reflection, two possibilities come to mind:

1) the daguerreotype was copied in the 19th century and photographically enlarged, then re-touched or painted over to yield a larger portrait that included her lap and hand, added by an artist. This reproduction was later photographed to produce the copies in the Portrait File and CHS.

or,

2) the original daguerreotype included her lap and hand, and it was re-daguerreotyped for family members in the 1850s, perhaps near the time of Anita’s 1855 death. When the copy daguerreotypes were made, they were composed more tightly in on the sitter, omitting the lap and hands. The newly acquired Bancroft daguerreotype could be a copy of a still earlier plate – and this earlier plate could be the source of the later paper copy in the Portrait file.

This will likely remain a mystery until other variants of this portrait surface. Are there other versions of this portrait of Anita de la Guerra de Robinson to be revealed?

Reference

Brewster, Michele M. “A Californiana in Two Worlds: Anita de La Guerra Robinson, 1821–1855.” Southern California Quarterly 102, no. 2 (2020): 101–42. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27085996.

Women Photographers Book Selections from the Richard Sun Donation

Here is a selection of books of the works of women photographers recently donated by Richard Sun. Additional books from the donation are now on display in the Art History/Classics library. Click the links to see their records in UC Library Search.

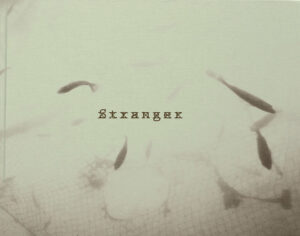

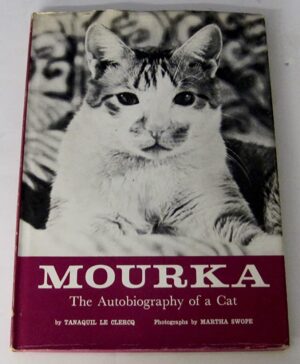

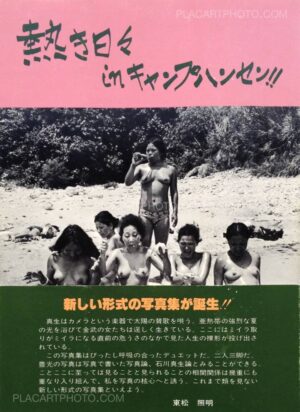

Stranger: Olivia Arthur Mourka: Martha Swope Hot Days in Camp Hansen: Mao Ishikawa

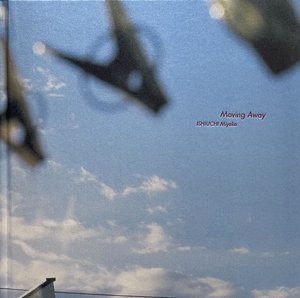

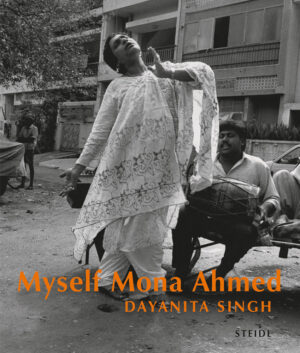

Liz Johnson Artur Moving Away: Ishiuchi Miyako Myself Mona Ahmed: Dayanita Singh

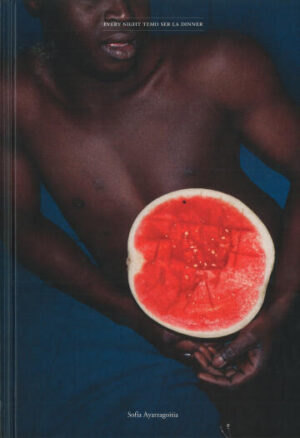

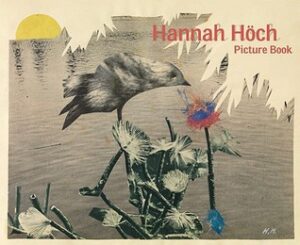

Memorandum: Ana Paula Estrada Every Night Temo Ser La Dinner: Sofia Ayarzagoitia Picture Book: Hannah Hock

Celebrating Women’s History Month in Art History

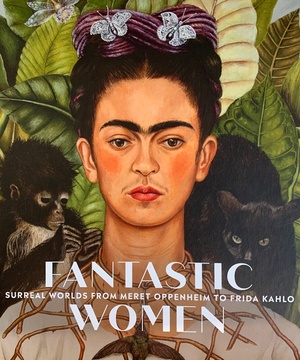

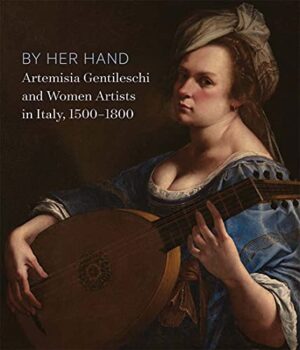

Check out these online resources available through UC Library Search. Click on the titles to view them in the catalog, or visit the Art History/ Classics Library to view new publications of women artists on display.

A time of one’s own : histories of feminism in contemporary art

Counterpractice : psychoanalysis, politics and the art of French feminism

Black Matrilineage, Photography, and Representation: Another Way of Knowing

The Art of Being Dangerous Exploring Women and Danger through Creative Expression

Women artists in the early modern courts of Europe (c. 1450-1700)

Women art workers and the Arts and Crafts movement

Griot Potters of the Folona : the History of an African Ceramic Tradition

Feminist visual activism and the body

Picturing political power : images in the women’s suffrage movement

New Art History Books for Women’s History Month

March is Women’s History Month. Check out these new Art History books on the Art History/Classics Library’s New Book Shelf, featuring women artists. Click the titles below to see them in UC Library Search.

Kara Walker Ladies First! Peintres Femmes

Femmy Otten Close-Up Sonya Clark

Celebrating Women’s History Month: Rare Images of the Winter War by Photojournalist Thérèse Bonney

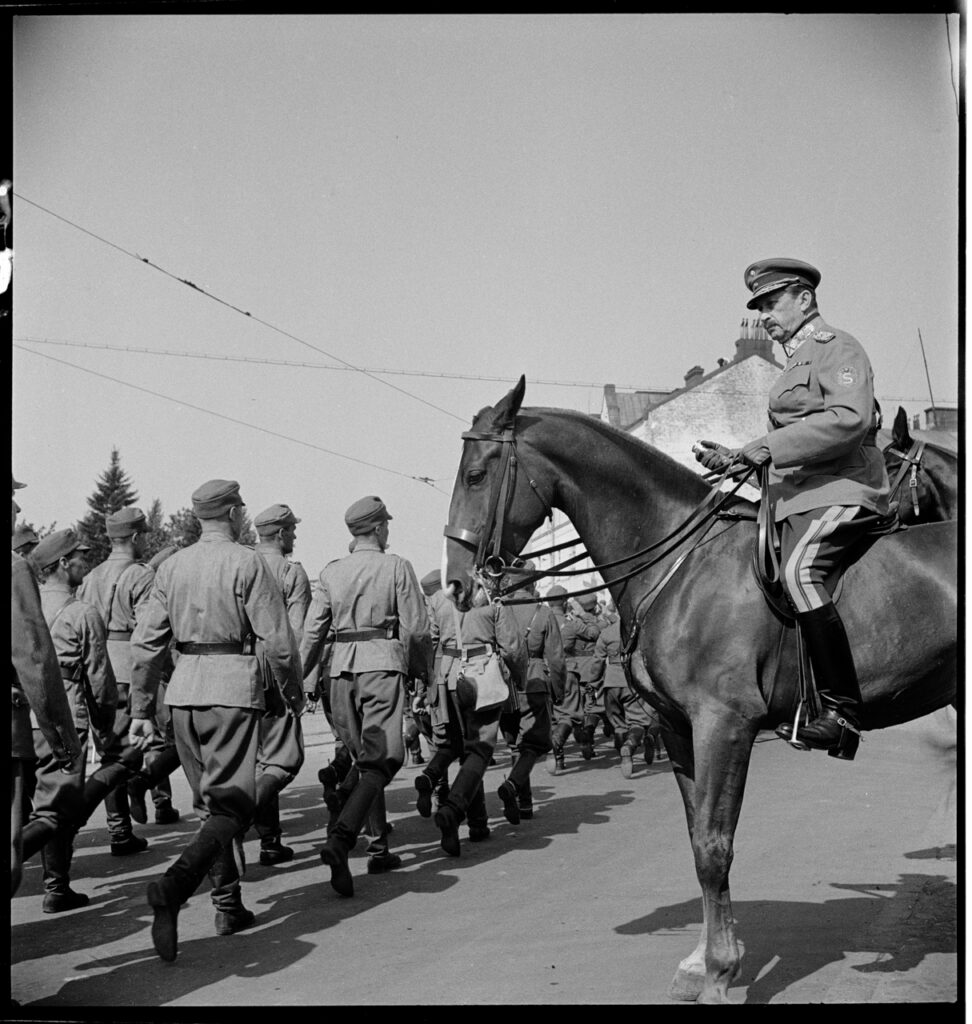

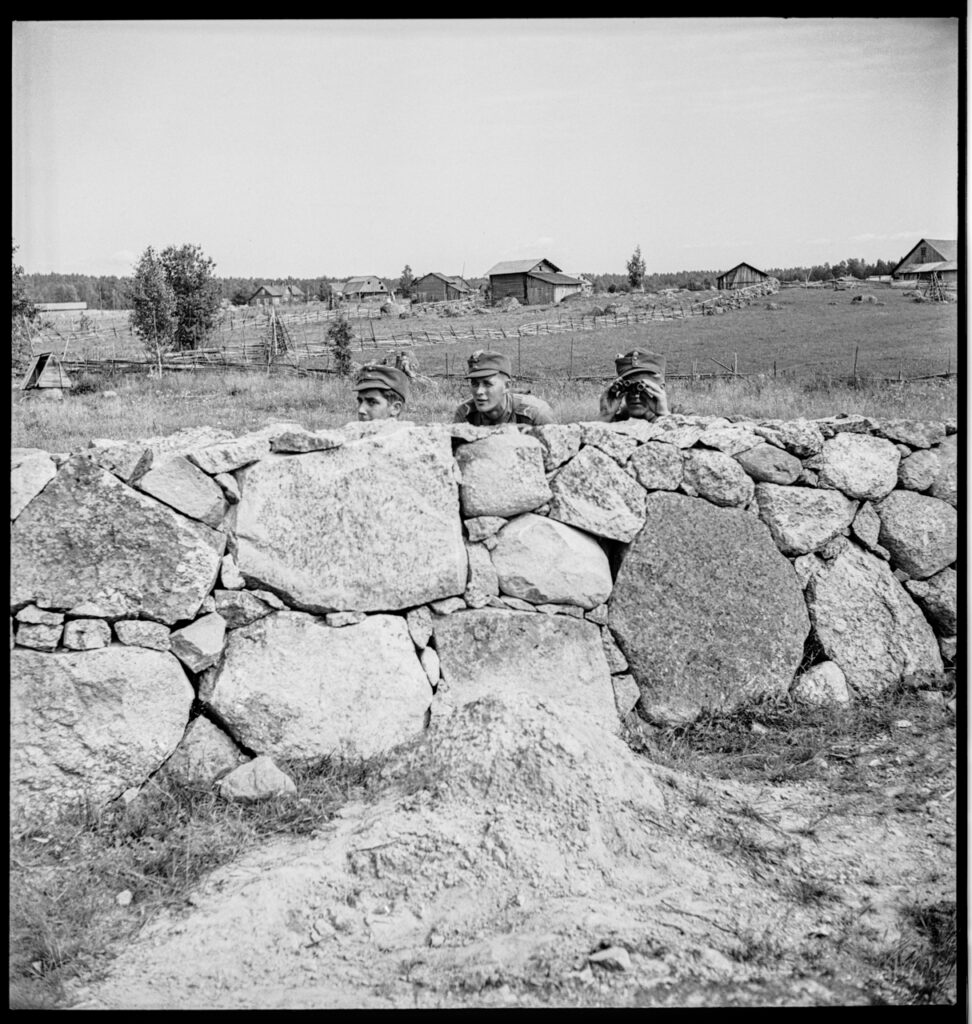

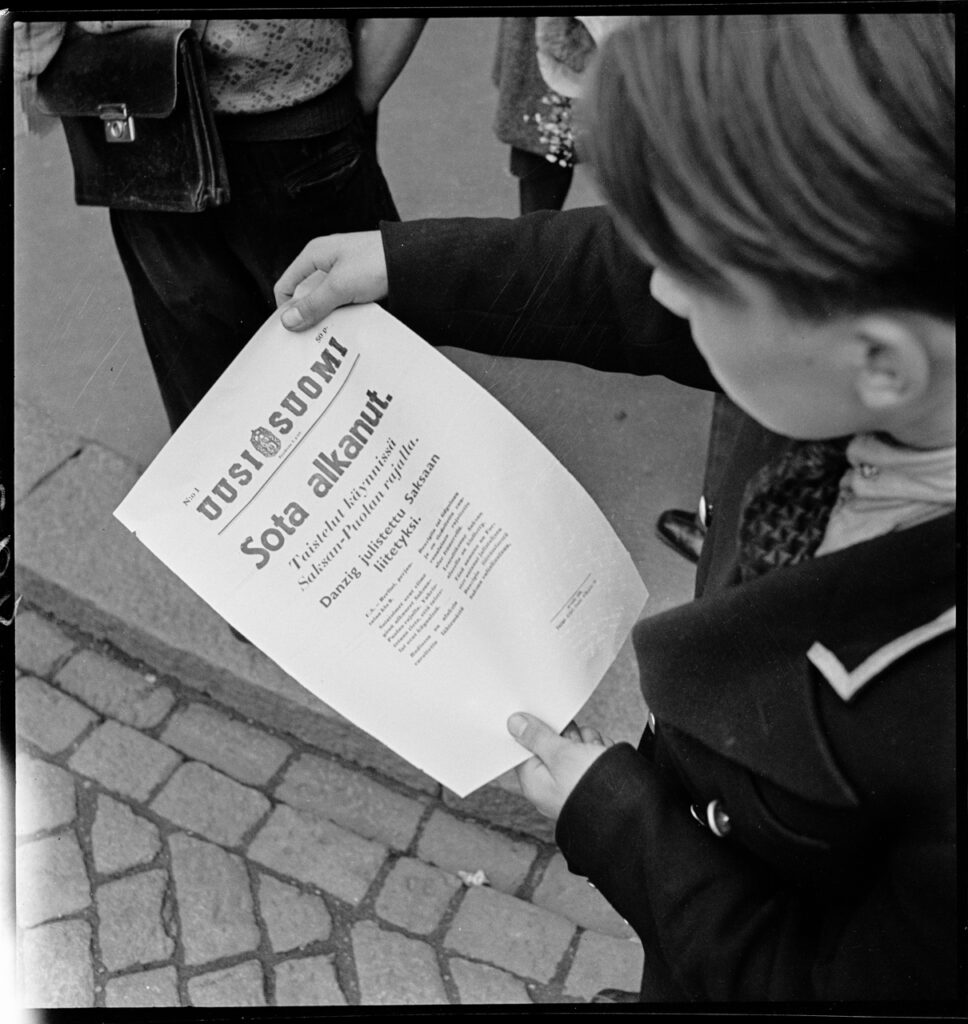

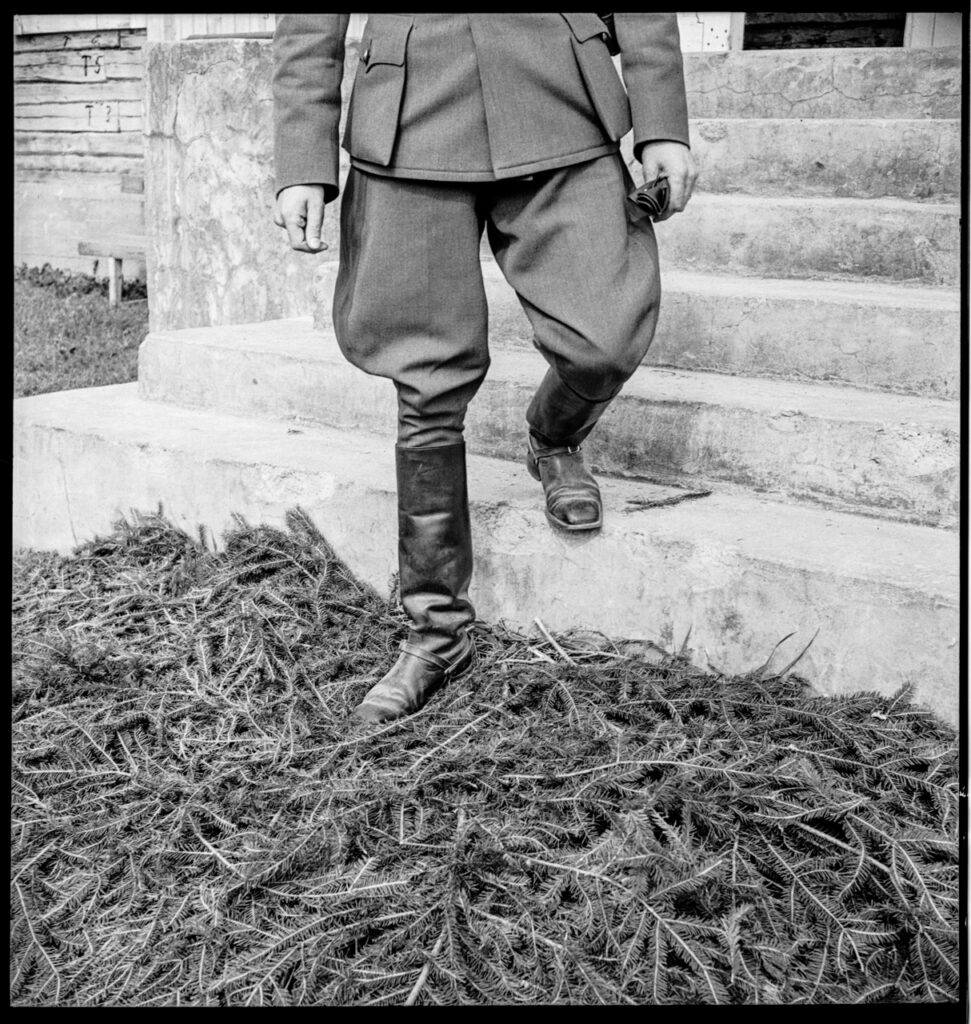

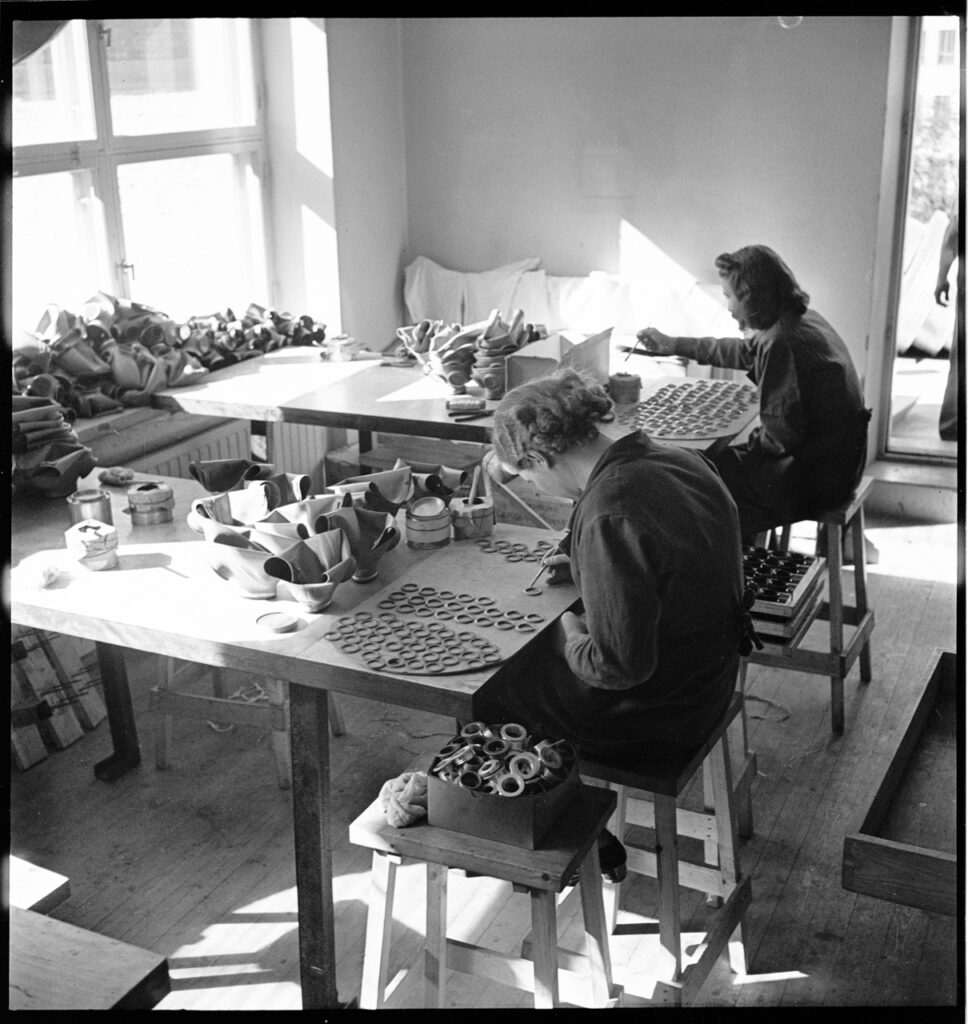

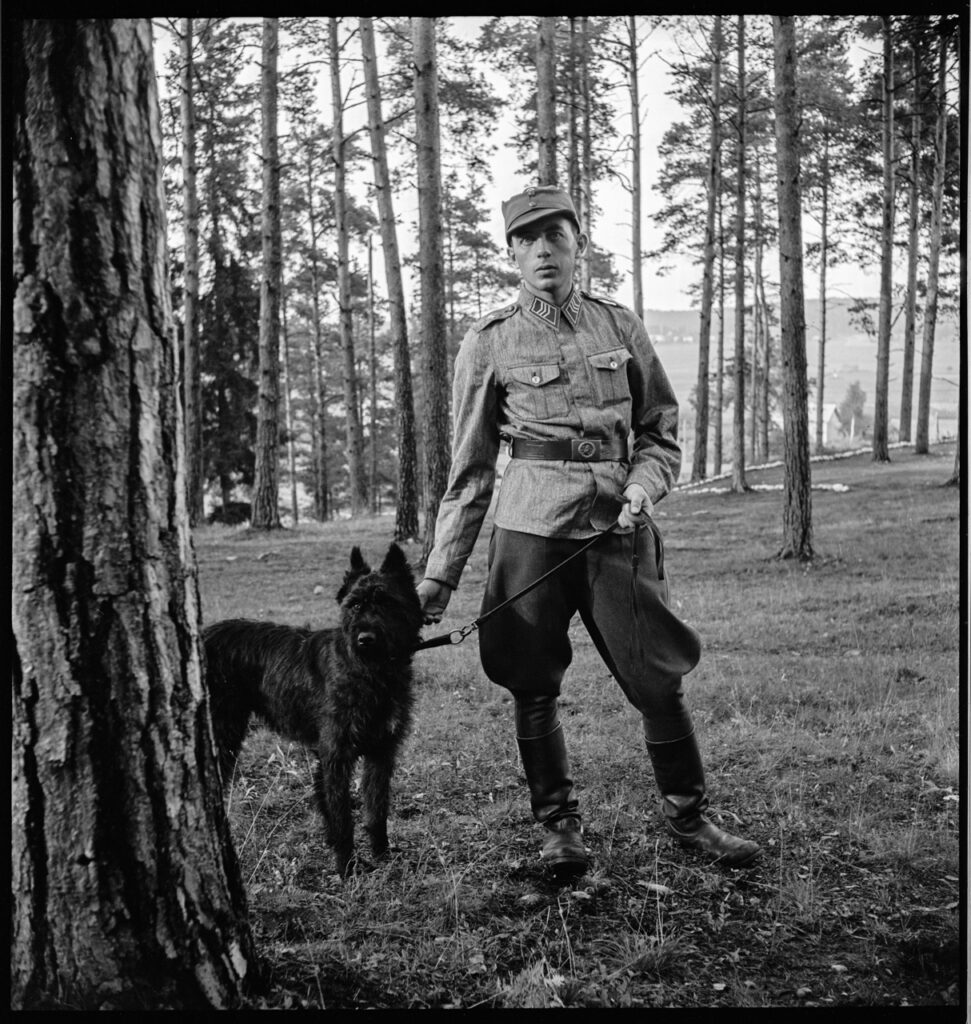

In the Autumn of 1939 Thérèse Bonney traveled to Finland to photograph preparations for the Olympic Games in Helsinki to be held the following year. Instead, she became a war correspondent. With World War II already underway, Bonney was one of few photographers in Finland as tensions with the neighboring Soviet Union grew. Bonney photographed Finnish military training operations leading up to the Soviet invasion on November 30, 1939. Throughout the ensuing Winter War she photographed civilian evacuations, relief operations, and meetings of Finnish leaders — work for which she was awarded the White Rose of Finland medal. The event would change the trajectory of her photographic career. Previously focused on French art and design, Bonney would go on to photograph throughout World War II, leaving an important record of the effect of war on civilian populations. Additional images of Bonney’s work in Europe during WWII can be seen in these previous postings: Wrapping up Women’s History Month: Selections from the Thérèse Bonney photograph collection at The Bancroft Library and Thérèse Bonney: Art Collector, Photojournalist, Francophile, Cheese Lover.

Still more is available via the Library’s Digital Collections site and the Finding Aid to the Thérèse Bonney Photograph Collection.

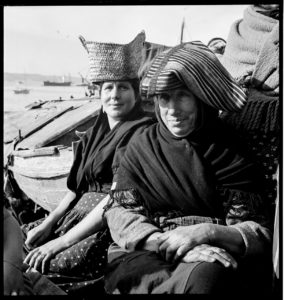

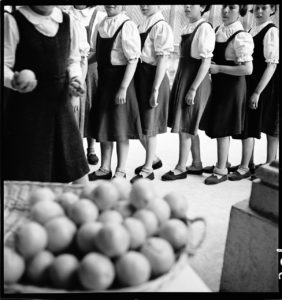

Wrapping up Women’s History Month: Selections from the Thérèse Bonney photograph collection at The Bancroft Library

The Thérèse Bonney photograph collection at The Bancroft Library consists chiefly of documentary photographs taken throughout Western Europe during World War II. Bonney (Berkeley class of 1916) photographed all aspects of the war, but focused on its effects on the civilian population.

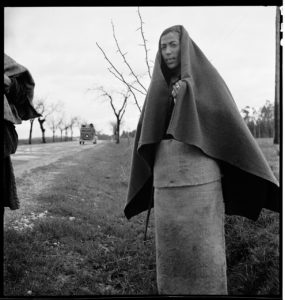

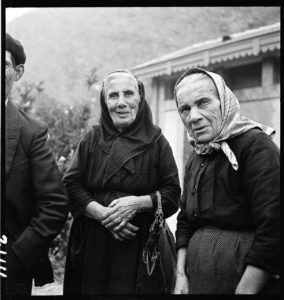

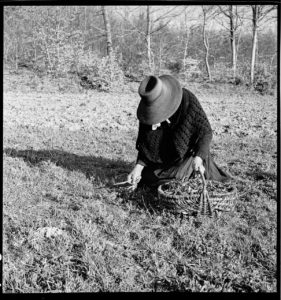

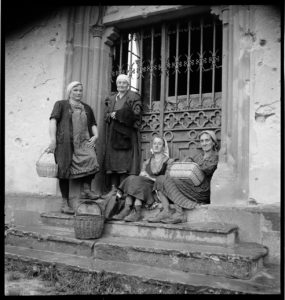

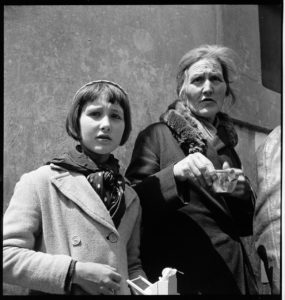

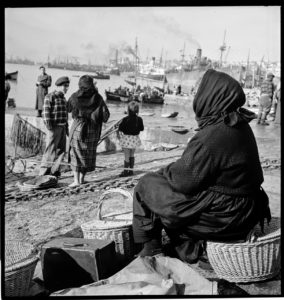

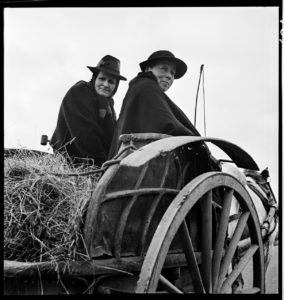

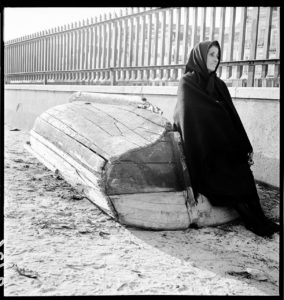

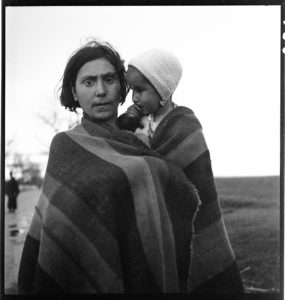

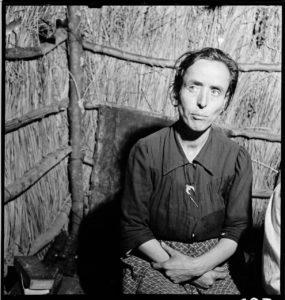

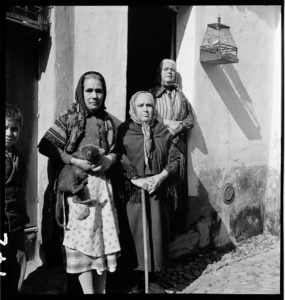

An active humanitarian, Bonney frequently used universal symbols in her work, allowing her images to speak beyond language barriers and leading their viewers to see beyond cultural differences. Her photographs of children were exhibited and published widely, influencing audiences to contribute to relief efforts for innocent victims of war. But the images throughout her archive feature another prominent symbol — women. Old women, young women, mothers, sisters, friends, neighbors; always at work, usually together, forever the epitome of personal sacrifice for the greater good. In honor of Women’s History Month, the Bancroft Library’s Pictorial Unit presents this collection of newly digitized images from the Thérèse Bonney Photograph Collection. The Finding Aid to the Thérèse Bonney Photograph Collection circa 1850-circa 1955 is available through the Online Archive of California. The finding aid includes digital images for Series 6: France, Germany 1944-1946. Images for Series 3: Carnegie Corporation Trip: Portugal, Spain, France 1941-1942 are coming soon, with a preview offered here!

“They Got Woken Up”: SLATE and Women’s Activism at UC Berkeley

For students across the country, college is a time of political awakening. And perhaps no other university has earned its reputation for radical student politics quite like UC Berkeley. Indeed, mid-century political activism around civil rights, the Vietnam War, and the Free Speech Movement has shaped how students, faculty, and administrators experience life at Berkeley today.

However, one important part of Berkeley’s political history that often gets left out of the conversation is the New Left student political party SLATE. SLATE — so named because the group backed a slate of candidates who ran on a common platform for ASUC (Associated Students of the University of California) elections — operated between 1958 and 1966, and ignited a passion for politics in the face of looming McCarthyism and what many perceived as the University of California’s encroachment on student rights to free speech. These students translated political theory they learned in the classroom to action, even when it went against University policies. Perhaps SLATE’s most important ideological contribution to Berkeley’s campus and to other social movements is the “lowest significant common denominator.” This concept allowed the group to form a big tent coalition between Marxists, liberal Democrats, and others by only choosing political positions and actions that the whole group could agree on. As a result, the group became involved with civil rights, labor organizing, and anti-war protests on campus and across California. Most notably, in May of 1960, SLATE and other student activists protested the HUAC (House Un-American Activities Committee) hearings at the San Francisco City Hall. In response to the peaceful sit-in, police blasted students with fire hoses and dragged them down stairs before placing them under arrest. This event was emblematic of SLATE’s commitment to activism, even when it came at personal risk.

In recent years, the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library has conducted a series of interviews with members of SLATE to keep alive memories of the group’s influence on ideology and political infrastructure at UC Berkeley.

An essential part of SLATE’s story is the contributions of its women members. SLATE operated at a time before the women’s movement, but its work became an important introduction to political organizing for a generation of women students at Berkeley. These women were dedicated members of the group, but often felt sidelined in SLATE leadership. And yet, their work helped to change political culture and campus life at Berkeley. Three of these groundbreaking Berkeley women are Cindy Lembcke Kamler, Susan Griffin, and Julianne Morris.

Cindy Lembcke Kamler was just a freshman when she connected with SLATE in the spring of 1958, drawn in by the political ideals of the group dominated by male upperclassmen and graduate students. Susan Griffin and Julianne Morris were among the second generation of SLATE activists and joined the group around the same time in 1960 — after the famous HUAC protest.

All of these women came from politically left families who feared encroaching McCarthyism. Griffin and Morris also had connections to Judaism. These backgrounds helped ignite a political consciousness in these women that led them to SLATE.

Certainly Kamler, Griffin, and Morris’s oral histories contribute to the larger archive of SLATE history, but they also speak specifically to their experiences as women in this group. For instance, Griffin and Morris recalled instances of feeling marginalized and of being left to do what Morris called the “scut work,” like mimeographing fliers and cooking for hungry activists. This work, while essential to maintaining operations, felt to them like gendered tasks. For her part, Kamler doesn’t remember gender discrimination in SLATE. She insisted, “Oh, no, I never made coffee or any of that stuff.” And yet, Griffin recalled that several years later at a meeting of SLATE women in the 1970s,

“We were recounting how there was this prejudice against us and we were never allowed to have leadership positions. And husbands and boyfriends and guys from SLATE showed up at this meeting and started making fun of us and broke the meeting up. They thought that was the end of the story. Little did they know, [laughs] that was just the beginning of the story.”

These tensions came to a head at a 1984 SLATE reunion in which women newly empowered by feminism expressed displeasure with the way they had been treated while working for the campus political group. Many of the men denied there had been discrimination, but others took it to heart and sincerely apologized. Morris explained, “There were a lot of women who were really angry about how it had been. I don’t know that I was angry, in the sense that I really felt it was a different time and one can’t judge one time by another. But there was no question that that’s the way it was, and that’s what kind of was accepted.” Watching these events unfold, Kamler recalled, “I was just sitting there stunned. I didn’t do any of that stuff. I ran for office, I got elected, I was chairperson.”

Indeed, while there may have been invisible barriers for many of the women involved in SLATE, there were still opportunities to grow as individuals and leaders. Kamler ran for second vice president in the spring of 1958 and lost, but ran again for representative-at-large in spring of 1959 and won. She also served as the chair of SLATE for some time, helping to shape the group’s platform and activist agenda. Even Griffin and Morris were encouraged to run for ASUC office in the early 1960s, and had to learn how to campaign and feel confident in public speaking. Morris especially found running for office to be a formative experience. She remembered,

“And that was, for me, a big experience, because as I said, I was shy in terms of speaking out and I didn’t think that I could do it. And Mike Miller kept urging me to do it and saying, ‘You can do this. I’ll help you if you want, but you can do this! You’re going to be able to go to all of these fraternities and talk to them about ROTC. I just know you can do it.’ So I did it, and I really was very frightened about doing it, and I actually did fine. So that was, for me, kind of a breakthrough, that I was able to do something like that, because it wasn’t easy for me at the time.”

But as their lives became less centered around the UC Berkeley campus, these women drifted away from SLATE. Kamler married and left the group after the spring of 1960. Griffin and Morris had decreased their participation in SLATE or left campus entirely by 1964. And yet, as their oral histories reveal, the experiences these women had as Berkeley undergraduates in this student political party shaped their perspectives about politics and activism for years to come. For both Griffin and Morris, this activism took shape as involvement in the women’s movement. Griffin explained, “The guys may not have known it, but they were training feminist activists in all that period.”

Thinking about the longer arc of SLATE’s impact on the lives of its dedicated members, Morris recalled of a reunion in the 1990s:

“One of the things that we did was that we went around as a group and talked about what our lives were like now. And no one in that whole group went into business. Everybody was an organizer, a teacher, a social worker, a psychologist. It was so interesting that this group of people kind of, in some ways, stayed true to what we all went through in college. It really formed our lives.”

But most importantly, what these women learned from their time with SLATE was the importance of building and sustaining community in activist groups. For Morris, joining SLATE helped her find a place where she belonged. Griffin pointed to organizations of politically like-minded individuals as ways to create belonging and “joy” through an almost spiritual experience of protest.

And yet, the political work of Cindy Lembcke Kamler, Susan Griffin, and Julianne Morris wasn’t just personally fulfilling. For these individuals and generations of other women students, their political activism at UC Berkeley left an indelible mark on the campus. In thinking of this legacy, Morris reflected, “…it was one of the first…of the Left student movements. And I think it influenced a lot of people in that regard…I’m not at all sure that the Free Speech Movement would have happened without SLATE.” She concluded, “I think we were very successful in those years. We got a lot of people elected to the campus political organization, and I think people started thinking, at Cal, a little differently. They got woken up in a way that perhaps they would not have been.”

To learn more about these activist women at Berkeley and the history of this early student political party, check out the Oral History Center’s SLATE Oral History Project.