Tag: women photographers

Celebrating Women’s History Month: Rare Images of the Winter War by Photojournalist Thérèse Bonney

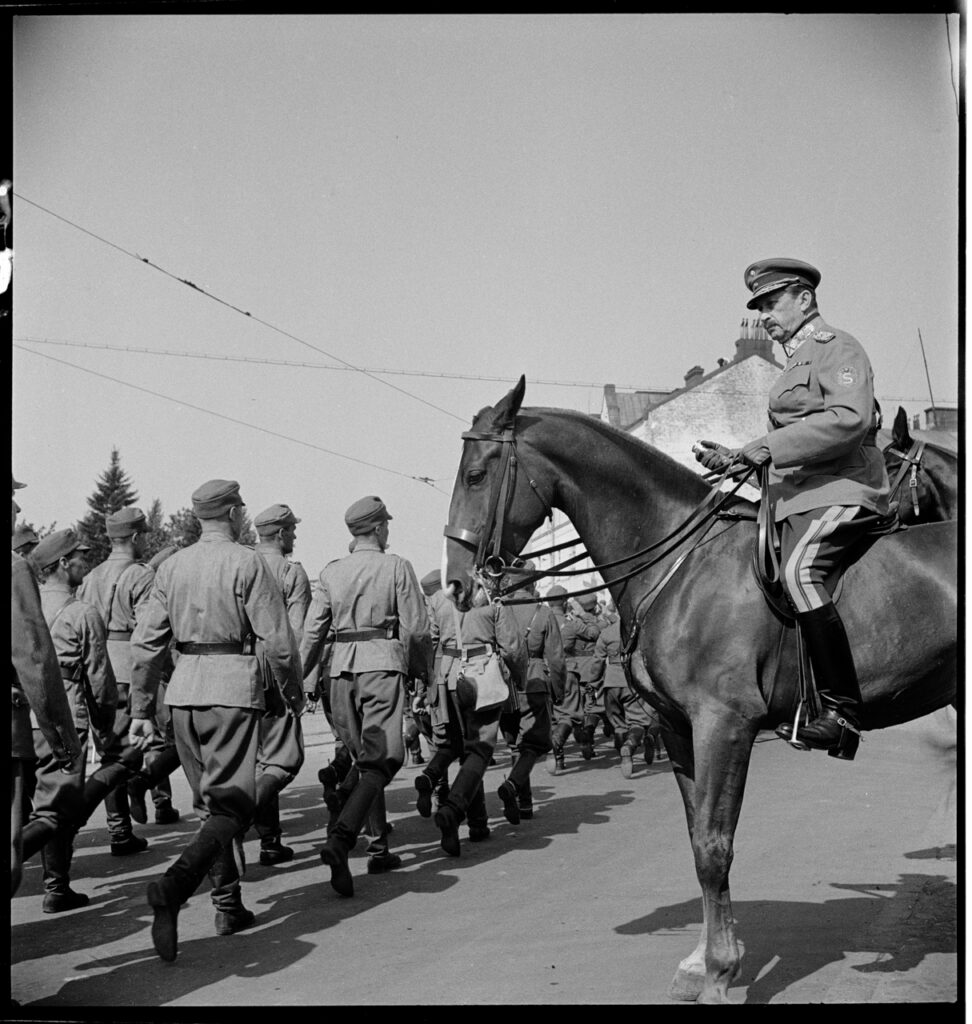

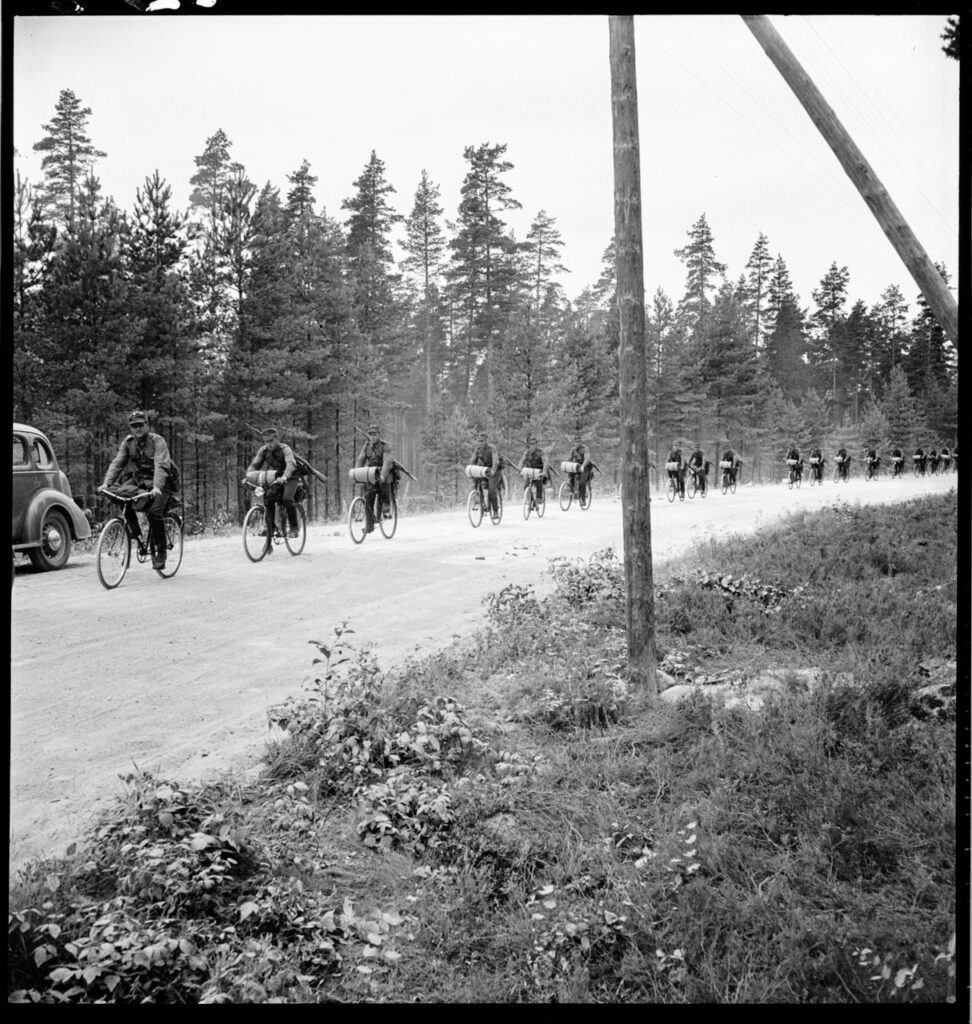

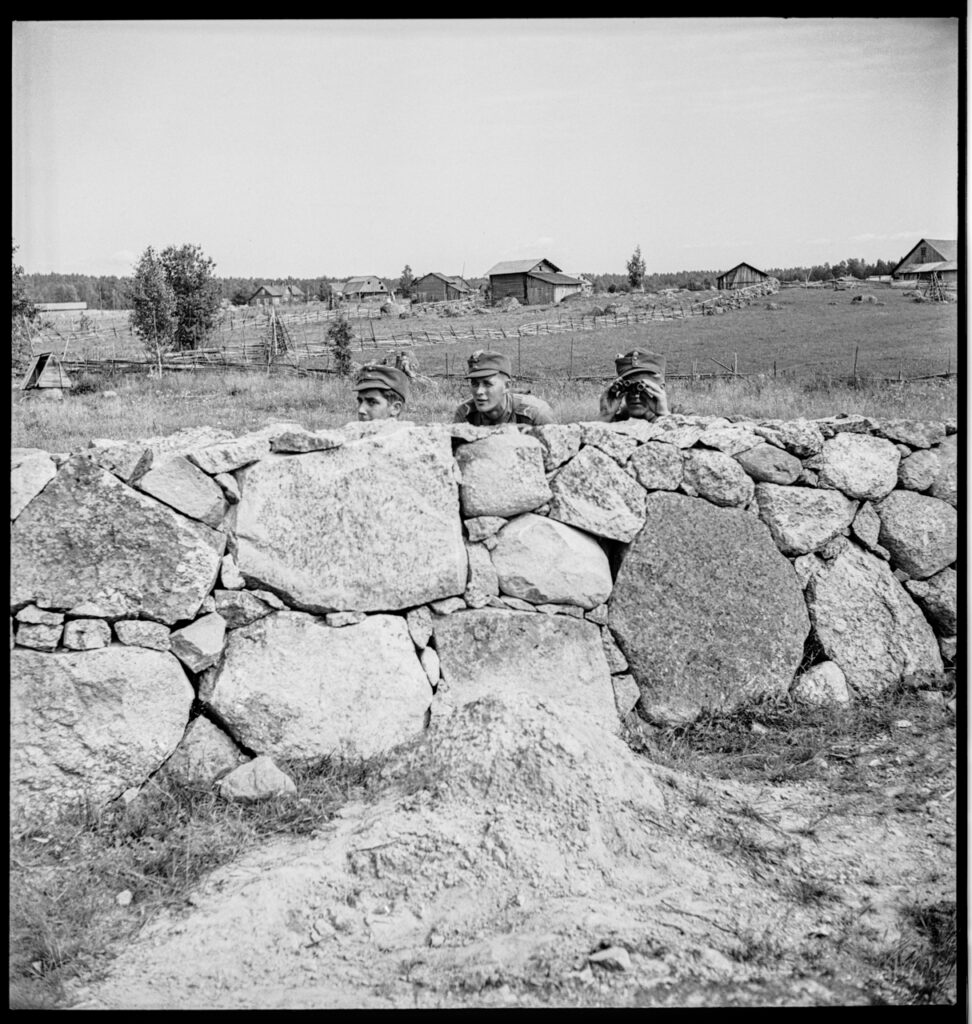

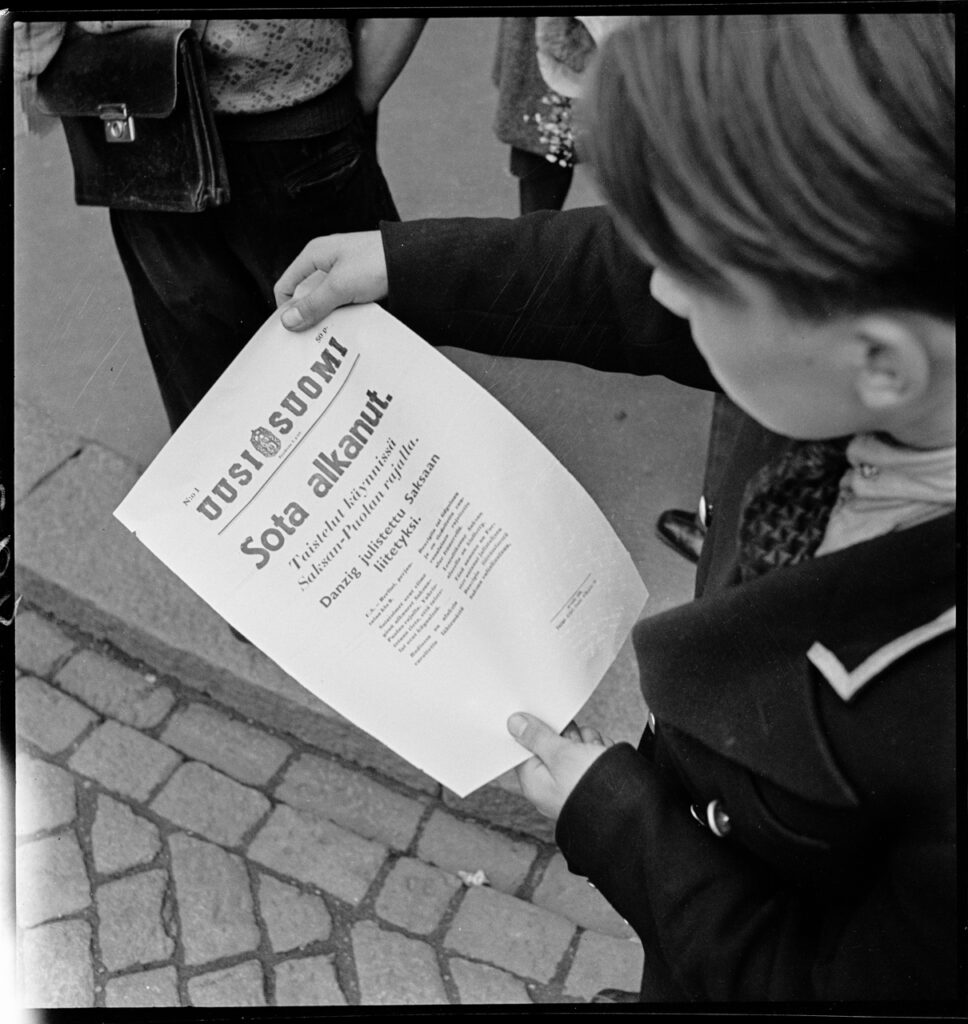

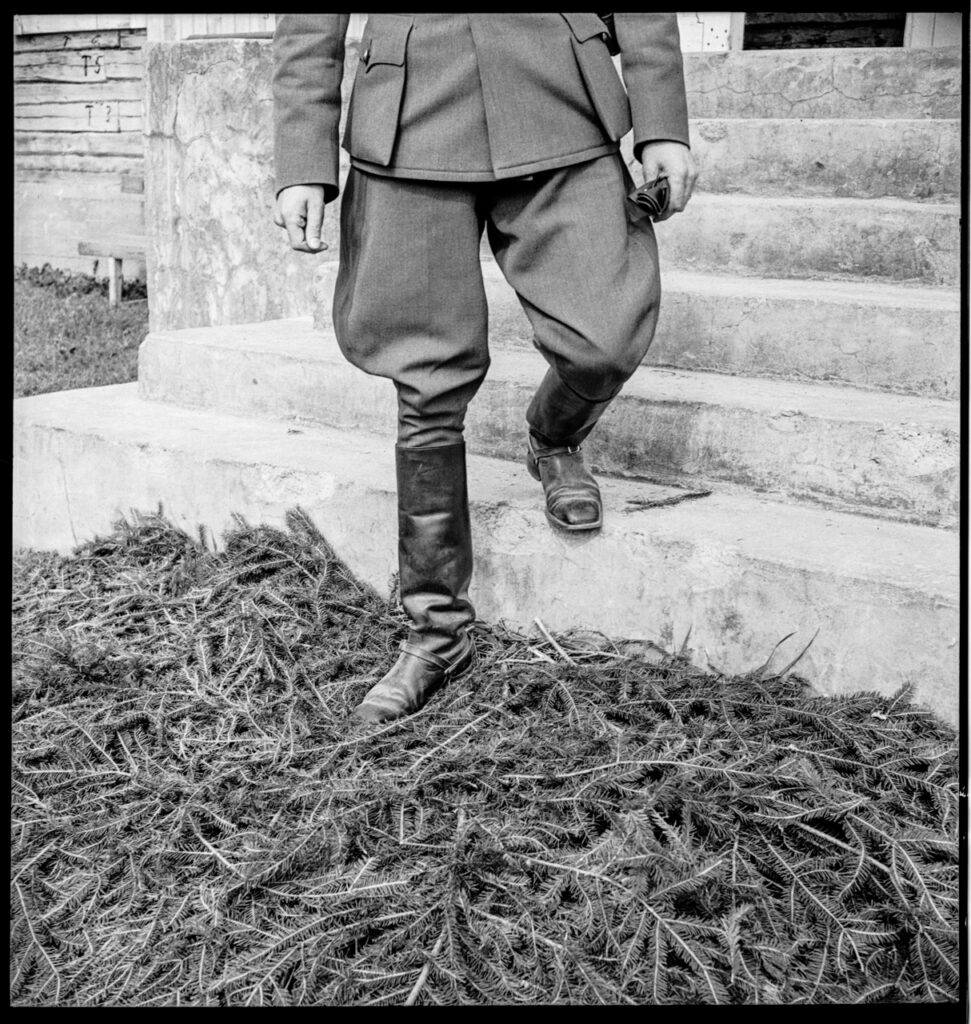

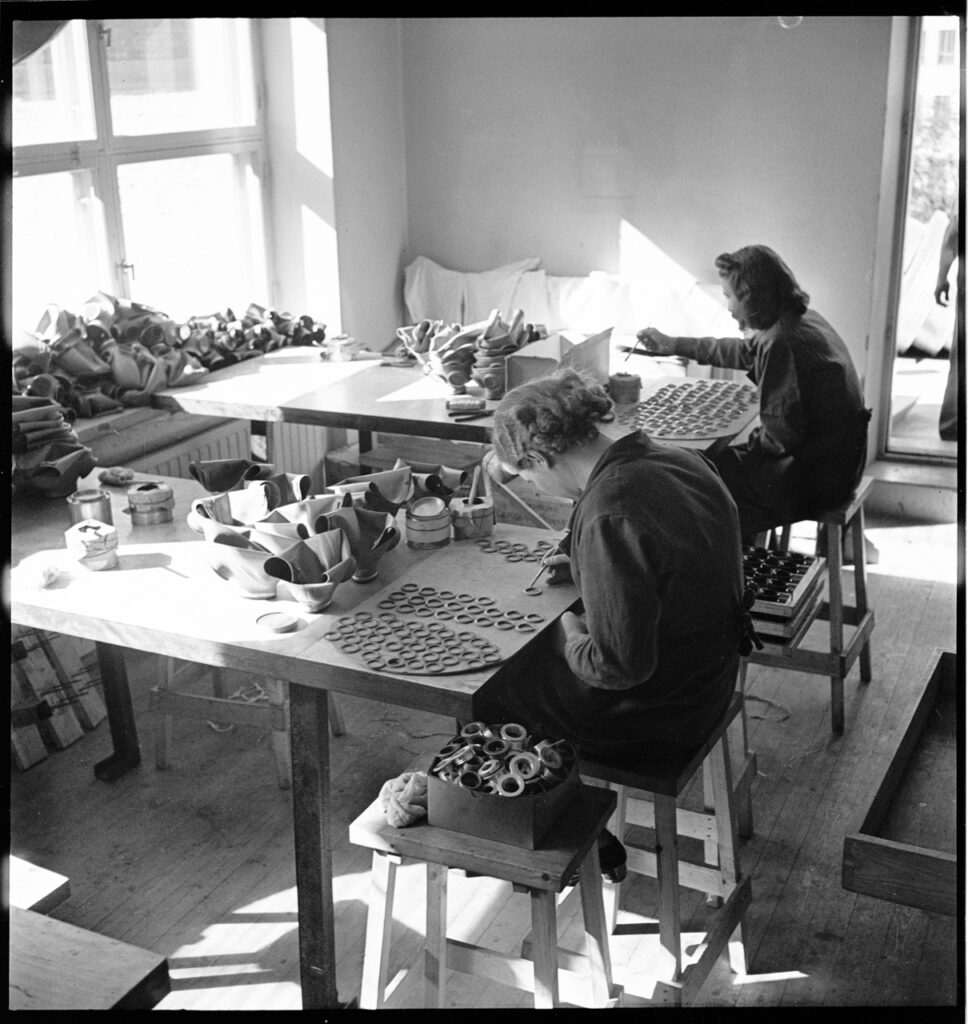

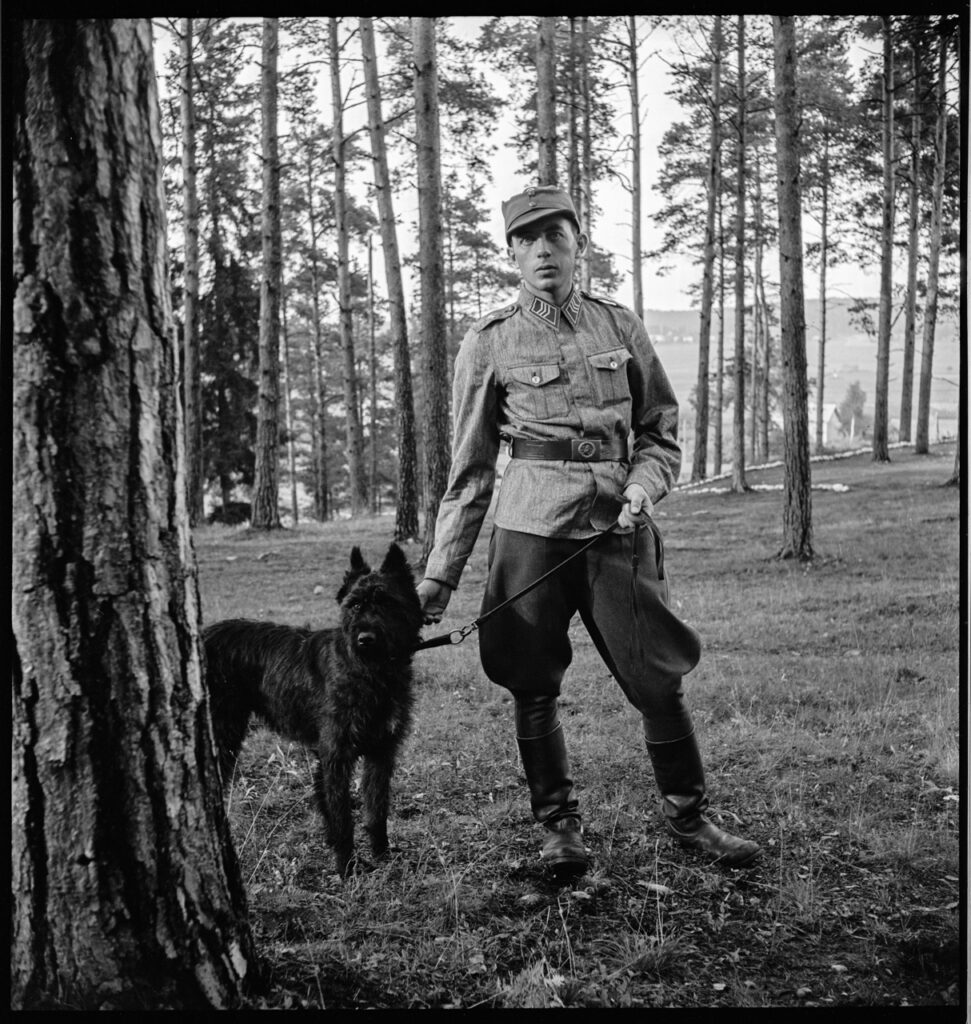

In the Autumn of 1939 Thérèse Bonney traveled to Finland to photograph preparations for the Olympic Games in Helsinki to be held the following year. Instead, she became a war correspondent. With World War II already underway, Bonney was one of few photographers in Finland as tensions with the neighboring Soviet Union grew. Bonney photographed Finnish military training operations leading up to the Soviet invasion on November 30, 1939. Throughout the ensuing Winter War she photographed civilian evacuations, relief operations, and meetings of Finnish leaders — work for which she was awarded the White Rose of Finland medal. The event would change the trajectory of her photographic career. Previously focused on French art and design, Bonney would go on to photograph throughout World War II, leaving an important record of the effect of war on civilian populations. Additional images of Bonney’s work in Europe during WWII can be seen in these previous postings: Wrapping up Women’s History Month: Selections from the Thérèse Bonney photograph collection at The Bancroft Library and Thérèse Bonney: Art Collector, Photojournalist, Francophile, Cheese Lover.

Still more is available via the Library’s Digital Collections site and the Finding Aid to the Thérèse Bonney Photograph Collection.

Photobooks by Women in the Reva and David Logan Collection

A posting by Christine Hult-Lewis, Ph.D., Reva and David Logan Curatorial Assistant

Tucked in the shelves of the Bancroft Library’s Reva and David Logan Collection of Photographic Books are some exceptional photography books by women photographers. Books illustrated with photographs were and are incredibly important in the history of photography: they are the best means to disseminate an artist’s work, are more readily available than photographic prints, and can wield an outsize influence in the public arena. Here is a selection of some of the most significant books by women in the collection.

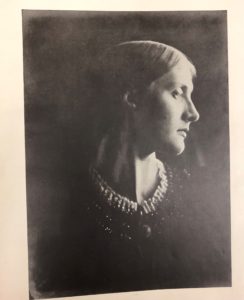

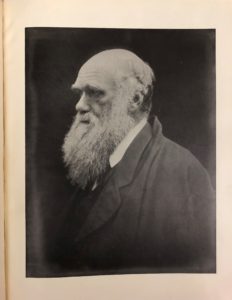

EARLY MASTERS

One of the best known and most influential photographers of the nineteenth century is Julia Margaret Cameron, whose insightful and penetrating soft-focus portraits redefined the genre. Cameron was most interested in getting at the “truth” and “beauty” of her subjects; her best portraits strip away all context in favor of a focus on the face itself, as in the above image of her niece Julia Jackson (Virginia Woolf’s mother). Some forty-seven years after Cameron’s death, Victorian Photographs of Famous Men and Fair Women was published by Woolf, who also contributed an introduction.

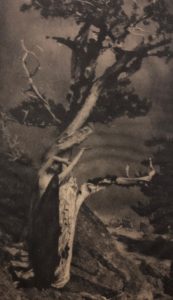

Most women didn’t produce their own books until the early decades of the twentieth century, but some shared their work in the pages of Camera Work. This seminal photography periodical, edited by Alfred Stieglitz from 1903-1917, regularly featured women in its pages, such as Gertrude Käsebier, whose work appeared in the inaugural issue, and Annie Brigman. Both used the familiar techniques of Pictorialism—soft focus, romantic subject matter—in their beautifully printed photogravures. Each addressed different aspects of the female experience: Käsebier emphasized the maternal bond and motherhood, while Brigman focused on the symbolically-charged interplay between women’s bodies and the natural world.

The Pictorialist aesthetic championed by Käsebier, Brigman, and others would continue into the 1920s and 30s with photographers like Doris Ulmann. Ullman was interested in rural America and folk cultures, part of a general reassessment of what constituted authentic “American-ness” during the 1930s. The result was the 1933 collaboration Roll, Jordan, Roll, with Ullman providing the delicately-printed photogravures and author Julia Peterkin providing text. The book describes the lives of the Gullah people, many of whom were former slaves living in the coastal areas of South Carolina and Georgia. Ulmann’s images provide a sensitive and nuanced portrayal of lives lived in quiet dignity.

DOCUMENTARY PHOTOBOOKS OF THE 1930s

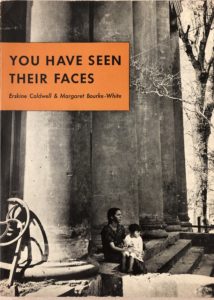

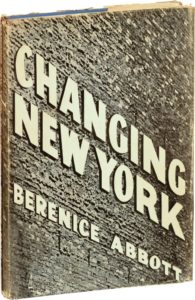

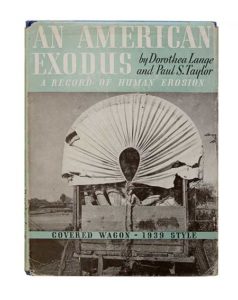

Some of the most influential photographic books of the Depression era were by women. Margaret Bourke-White’s You Have Seen Their Faces concentrated on what she and Caldwell perceived as the ongoing problems of the South: its extreme poverty, its pernicious and ongoing racism, and its damaged people. The book was popular, though it had, and has, its detractors, who objected to its condescending tone. By contrast, Dorothea Lange was one of the most respected practitioners of documentary in the 1930s, and made sure to give her subjects their own voice(s). Lange worked under the aegis of the US government-sponsored Farm Security Administration, taking photographs intended to help support the various projects of agricultural reform. This book was a true merger of empathetic, artistic images and dispassionate, statistical text. Another government-sponsored project, Berenice Abbott’s Changing New York, shifted the attention from rural people in distress to the changes and dislocations of that quintessential American city, New York. Abbott was particularly attuned to the beauties of the ever-changing city, and the transformations wrought by that peculiarly modern structure, the skyscraper.

PHOTOJOURNALISM

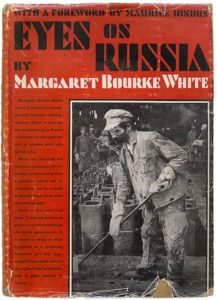

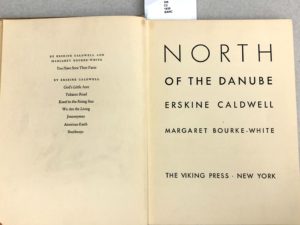

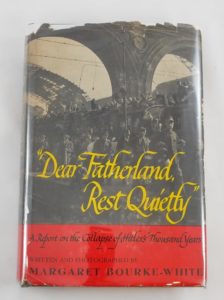

Margaret Bourke-White wasn’t really a documentarian; her true metier was photojournalism. She worked for the earliest pictures magazines in the United States, Fortune and Life. Bourke-White was the first photographer to go to Soviet Russia; sent there by Fortune in 1930, her experiences there became the book Eyes on Russia. Concurrently with her work on picture magazines, she wrote or co-wrote twelve books, five of them during the war years. She spent much of the war in the European theater of operations, where she became accredited as an official Army Air Force photographer. She worked incessantly, took all kinds of risks, made thousands of pictures, and managed to churn out books at an astonishing rate. North of the Danube recounts the months when Germany invaded Austria and Czechoslovakia, while Dear Fatherland, Rest Quietly attempts to grapple with the horrors of the Holocaust. The Logan Collection has fine examples of every one of her books.

THE 1970s

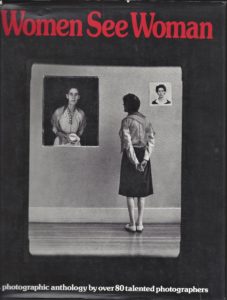

By the 1970s, the lack of women in the photographic canon did not go unnoticed by women artists, feminists, and their allies, and they sought to redress this exclusion and promote a more inclusive point of view. This took place in not only in museum exhibitions but also in photobooks, including anthologies like these that sought to uncover the work of women photographers whose names had dropped off the radar of popular culture and photographic history.

New monographs by young photographers like Judy Dater explicitly explored gender, examining different conceptions of femininity, sexuality, and agency in portraiture. Dater’s work can be seen as a kind of modern extension of Julia Margaret Cameron, in her explorations of the human psyche through expression, gesture, and light itself. Diane Arbus—this book of her photographs would not be released until after her death in 1971–would redefine the documentary project with her highly-charged photographs in the 1960s. Like Bourke-White, she took risks and went where others dared not go; she could almost be described as a photojournalist of the psychological.

The Logan Collection is a wonderful resource to study the photobooks by women, as well as many other themes in the history of photography. I hope this brief overview of this collection sparks further study. For more information, see the online overview of the Logan Collection. Books are available for onsite use in Bancroft’s reading room, and can be requested from OskiCat via our online paging system.