Tag: oral history center

“Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism,” an Oral History Center exhibit in The Bancroft Library Gallery

We’re excited to announce the opening of Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism, a Bancroft Library Gallery exhibition that was curated by Todd Holmes, Roger Eardley-Pryor, and Paul Burnett of the Oral History Center. Voices for the Environment traces the evolution of environmentalism in the San Francisco Bay Area across the twentieth century. In three sections, it highlights how Bay Area activists have long been on the front lines of environmental change—from efforts to preserve natural spaces in the wake of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, to the midcentury fight for state regulations to protect San Francisco Bay shoreline, to more recent demands for environmental justice to address the disproportionate burden of pollution that sickened communities of color around the Bay.

Our Voices for the Environment exhibit is the first major effort in The Bancroft Library Gallery to showcase oral history alongside the traditional archival collections of The Bancroft Library, with the oral history collections leading the way. The exhibit still features historic photographs, pamphlets, post cards, and posters selected from several collections of The Bancroft’s physical archives. But for the first time in this gallery, our Voices for the Environment exhibit also includes three installations of special Audio Spotlight technology where you can listen to never-before-heard oral history recordings with Bay Area environmentalists, while simultaneously watching three videos edited by Todd Holmes that feature historic photographs and rare film footage from The Bancroft’s digital collections. Additionally, as a complement to the exhibit, curators Todd Holmes and Roger Eardley-Pryor created an educational workbook, so students of all ages can learn about the environmental movement by engaging with the themes and primary sources on display. Through these efforts, the Oral History Center hopes Voices for the Environment will have a life beyond its yearlong run.

For an even deeper dive, you can also scan a QR code in the gallery, or click the following link, to hear three Voices for the Environment podcast episodes produced in partnership with Sasha Khokha of KQED Public Radio and The California Report Magazine. The podcast episode for section 1 of the exhibit, titled “A Preservationist Spirit,” traces the environmental activism that arose amid the rebuilding efforts of San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake and fire, efforts that came to target the state’s ancient redwood forests and the beloved Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park. The episode features historic interviews from the Oral History Center archives including segments from the “Growing Up in the Cities” collection recorded in the late 1970s by Frederick M. Wirt, as well as oral history interviews with Carolyn Merchant recorded in 2022, with Ansel Adams recorded in the mid-1970s, and with David Brower recorded in the mid-1970s. The oral history of William E. Colby from 1953 was voiced by Anders Hauge, and the oral history of Francis Farquhar from 1958 was voiced by Ross Bradford. This first episode also features audio from the film Two Yosemites, directed and narrated by David Brower in 1955. The podcast episode for section 2 of the exhibit, titled “Tides of Conservation,” tells the story of the Save San Francisco Bay movement and the creation of the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC), one the nation’s first environmental regulatory agencies. The episode features segments from oral history interviews with Save The Bay founders Esther Gulick, Catherine “Kay” Kerr, and Sylvia McLaughlin recorded in 1985; as well as interviews with BCDC executive director Joseph Bodovitz and chairman Melvin B. Lane, both recorded in 1984. And the podcast episode for section 3 of the exhibit, titled “Environmental Justice for All,” spotlights efforts by communities of color to place the health of people within the environmental agenda, including creation of new environmental organizations like the West County Toxics Coalition, the Urban Habitat Program, and APEN (Asian Pacific Environmental Network), all founded in the Bay Area. The episode features segments from oral history interviews with Carl Anthony, Pamela Tau Lee, Henry Clark, and Ahmadia Thomas, all recorded in 1999 and 2000.

The Voices for the Environment exhibition space was designed by Gordon Chun and is free and open to the public Monday through Friday between 10am to 4pm from Oct. 6, 2023 to Nov. 15, 2024, in The Bancroft Library Gallery, located just inside the east entrance of The Bancroft Library.

We hope you come to campus and experience it!

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. While we receive modest institutional support, we are a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. We must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

Senga Nengudi: Black Avant-Garde Visual and Performance Artist

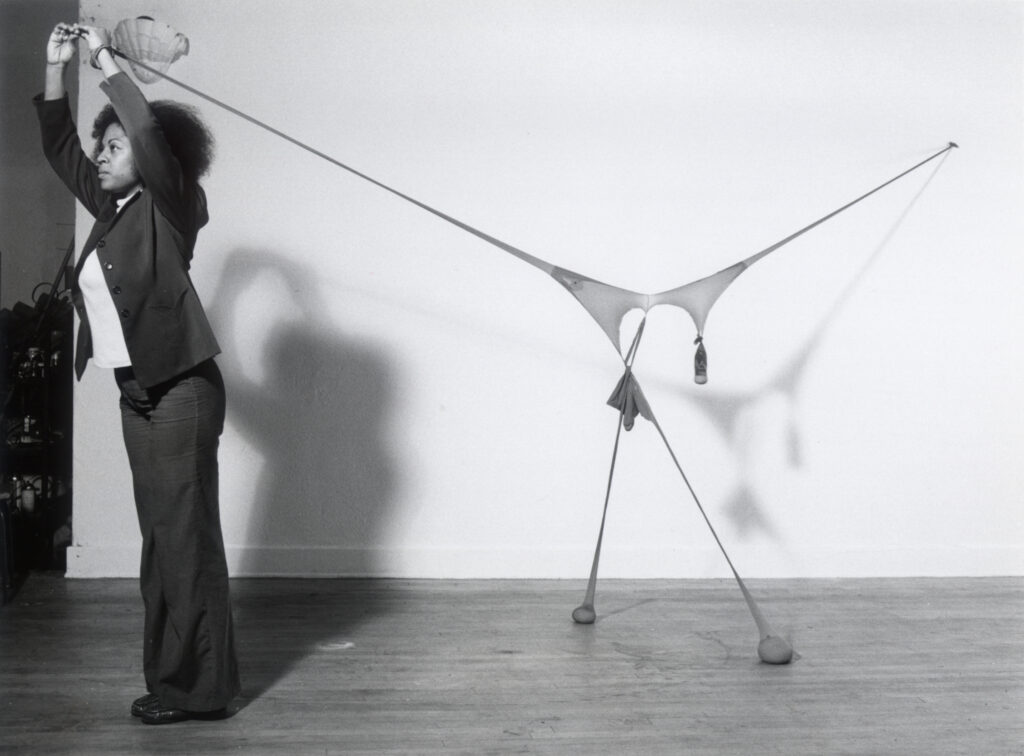

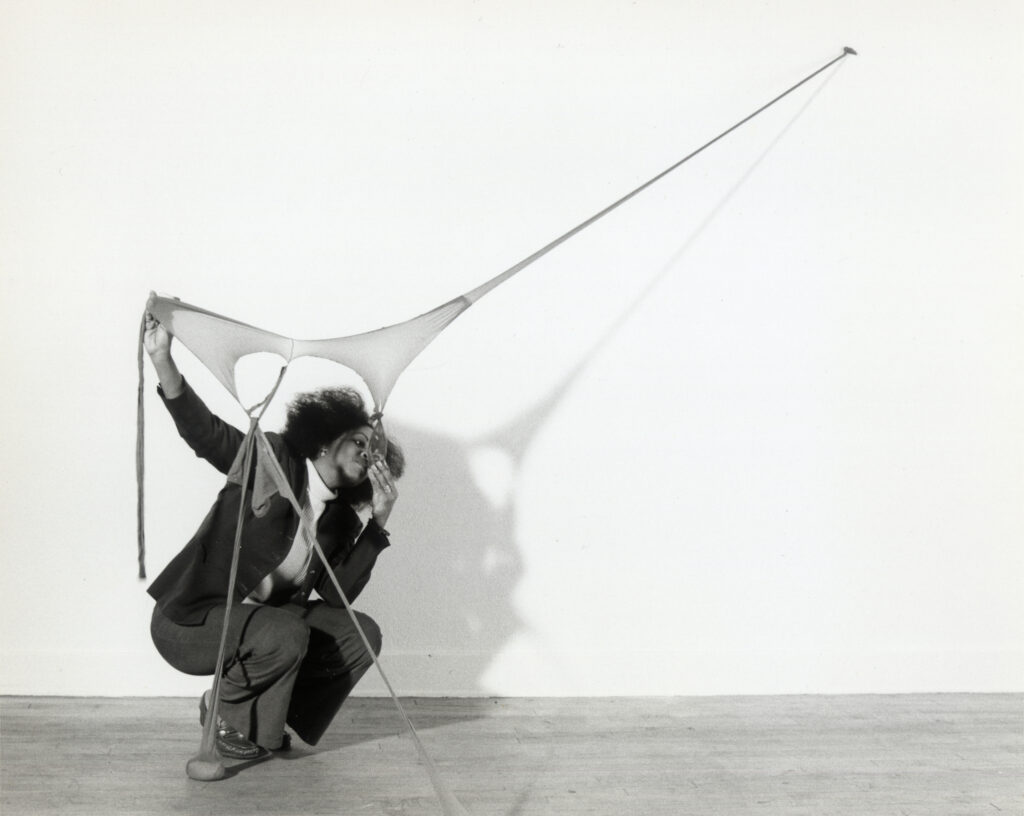

As a continuation of our work for the Getty Research Institute’s African American Art History Initiative (AAAHI), Dr. Bridget Cooks and I conducted several oral history interviews with the avant-garde artist Senga Nengudi. This interview is one of several AAAHI oral histories exploring the lives and work of Los Angeles-based artists, and highlights Nengudi’s contributions to visual and performance art.

Senga Nengudi is an avant-garde artist best known for her abstract sculpture and performance art. Nengudi was born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1943 and moved to Los Angeles, California, at a young age. She attended California State University, Los Angeles (CSULA) for both her undergraduate and master’s work, as well as completed a program at Waseda University in Tokyo, Japan. Nengudi was active in the avant-garde Black art scenes in Los Angeles and New York during the 1960s and 1970s, and was a member of the Studio Z Collective. She is best known for her R.S.V.P. (Répondez s’il vous plaît) Series featuring pantyhose, which she began in 1975. Nengudi is the recipient of many awards, including the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Award in 2005, the Anonymous Was a Woman Award in 2005, the Denver Art Museum Key Award in 2019, and was elected as a member to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2020. Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Senga Nengudi was still in elementary school when she and her mother moved to Los Angeles in the early 1950s. Despite a brief stint in New York, for more than thirty years she lived in the greater Los Angeles area first as a child; as a student at CSULA; as an artist and active member of the Studio Z Collection; and as a young mother. That Nengudi called Los Angeles home for so long meant that her formative years of creative expression and early artistic networks sprang from the Southland.

Looking back, Nengudi credits her mother with providing a creative foundation.

“…she was very, very, very conscious of the home and making something home, and so she would decorate the house. And then, say like three years later, she would repaint the walls, she would change the upholstery, she would do all those kinds of things. She was very aesthetically aware, as well as needed a particular beauty in her home to feel good.”

And Nengudi expressed her own creativity through several outlets, remembering, “It’s always been a deal between art and dance with me…” Indeed, during her undergraduate years at CSULA, she chose to major in art and minor in dance—a pairing which supports much of her work.

In the mid-1970s, Nengudi found an outlet to express her love of performance through the Studio Z Collective—a collective of artists interested in improvisation that continued into the 1980s. In addition to Nengudi, Studio Z was comprised of Houston Conwill, David Hammons, Maren Hassinger, and occasionally other artists including Franklin Parker and Ulysses Jenkins. Her relationships with these artists also had a great impact on Nengudi’s artistic career. Thinking of Studio Z’s contribution to her 1978 performance Ceremony for Freeway Fets, which took place under a freeway overpass on Pico Blvd., she muses that “we all kind of supported each other in our efforts.”

Nengudi also found early support from Los Angeles-based gallery owners like Greg Pitts at the Pearl C. Woods Gallery, as well as Brockman Gallery’s Alonzo and Dale Davis. In fact, Brockman Gallery’s dispersal of CETA [Comprehensive Employment and Training Act] funds helped employ artists like Nengudi and Maren Hassinger.

Hassinger remains Nengudi’s longtime creative collaborator. Nengudi recalls that the connection between the two was immediate, “We just kind of instantly became friends, because there was this commonality. She was involved with dance, she was involved with sculpture, all that kind of stuff.” And to why this collaboration with Hassinger has sustained both the passing of years and geographical distance, Nengudi explains:

“Because we believe so much in collaboration. We believe in unity. We believe in bringing the best out in each other…Even though our background is different, our interests are the same. It’s always been dance, performance, sculpture, movement, and this commitment to our art. And when we had some really funky times and we were 2,000 miles apart, the thing that held us together was this commitment to art. And so that kind of carried us through the most difficult things…So all these life events were going on, but the constant was our ability to connect and think and make happen.”

Nengudi’s most recognizable series of work is R.S.V.P., which she started in the mid-1970s. The R.S.V.P. Series, or Répondez s’il vous plaît (respond, please), demonstrated Nengudi’s experimentation with nylon pantyhose. Importantly, Nengudi began working in this medium after the birth of her first son, when she was especially interested in the elastic nature of a woman’s body. She recalls,

“So yes, the explorations were really exciting. I put eggs in them, I broke eggs in them…I used white glue, I used hot glue, which obviously didn’t last that long. I tried everything—resin. Again, it dissolved in the resin. So really, as I was developing the series, it was all about exploring the material…And it took a while to get to…the sand, where I just noticed that…once in the nylons, it had such sensuality to it, because it had this kind of natural body form from the weight of the sand.”

Given the experimental nature of her sand-filled nylon pieces, Nengudi explains, “I thought about them as sculpture first. I did not develop them thinking that I would perform in them.” But Nengudi eventually did embrace the performative potential of these sculptures, even engaging Hassinger to perform with them at the Pearl C. Woods Gallery in 1977 by entwining her body with the material, manipulating it, even dancing with it.

Nengudi has lived in Colorado since the 1980s, and continues to stimulate audiences by creating work that plays with the line between sculpture, installation, and performance in space. However, she has also made significant contributions as an arts educator, especially at University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, and as an advocate of the arts. Namely, she established a community art gallery called ARTSpace in Colorado Springs so that “artists could show their work” and learn “what it takes to have an art exhibit.” The added bonus, of course, was that “the community could come in and see the artwork. It was right there for them.” For someone whose early exposure to creative expression was so formative to her artistic practice, this is a logical next step to engage new generations of artists and viewers. It also connects with her decades-long entreaty to audiences: “respond, please.”

To learn more about Senga Nengudi’s life and work, check out her oral history interview! Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Oral History Center Celebrates “Graduates”

Spring is a time of year when things begin anew. Flowers bud new petals, days have new length, and college graduates embark on new careers. It’s also a time when we at the Oral History Center celebrate an exciting phase of our narrators’ lives: a new life in our archive, where their story will live on in perpetuity. Not only can a narrator’s loved ones, friends, and colleagues access their interviews for years to come, students, researchers, and scholars can learn something about a time and a place, illuminating an aspect of history they might not have previously considered.

One way the UC Berkeley Oral History Center (OHC) likes to usher in this new phase of a narrator’s life is to have a “graduation” ceremony to honor their participation in the oral history process. Traditionally, we did this in person at the Morrison Library here on UC Berkeley’s campus, but like many things, we’ve had to adjust in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, we like to list their names and the projects for which they were interviewed online and in our newsletter so that all those in the OHC’s community can celebrate their contributions with us from near and far.

Please join us in expressing our appreciation for our latest cohort of narrators, spanning from fall 2021 to spring 2023. We are grateful to have their voices in our collection and their stories a new part of the historical record.

We also want to thank the OHC team—Paul Burnett, David Dunham, Roger Eardley-Pryor, Shanna Farrell, Todd Holmes, Jill Schlessinger, and Amanda Tewes—for their work in making these interviews come to fruition, along with the support from our student employees, who are a valuable part of our process: Max Afifi, Mollie Appel-Turner, Hue Bui, Mina Choi, William Cooke, Georgia Cutter, Nikki Do, Adam Hagen, Jordan Harris, Vivien Huerta-Guimont, Ashley Sangyou Kim, Ricky Noel, Deborah Qu, Mela Seyoum, Lauren Sheehan-Clark, Joe Sison, Erin Vinson, Shannon White, Serena Williams, and Timothy Yue.

Bravo, Oral History Center Class of 2023!

Anchor Brewing Co.

Mark Carpenter

Gordon MacDermott

Fritz Maytag

Linda Rowe

Bay Area Women in Politics

Louise Renne

Ruth Rosen

J.J. Wilson

California Business

Fred Martin

California Cannabis

Oliver Bates

California State Archives State Government Oral History Program

Wesley Chesbro

Fran Pavley

Lois Wolk

Bill Lockyer

Chicana/o Studies

Adele de la Torre

Ignacio García

East Bay Regional Park District

Ira Bletz

Ginny Fereira

Neil Havlik

Carol Johnson

Doug McConnell

Ruth Orta

Bethia Stone

Jeff Wilson

Mark Taylor

Mae Torlakson

Tom Torlakson

Will Travis

Nancy Wenninger

Environment/Natural Resources

Mary D. Nichols

Getty Research Institute’s African American Art History Initiative

Marion Epting

Maren Hassinger

Leslie King-Hammond

Thaddeus Mosley

Sylvia Snowden

William T. Williams

Vickie Wilson

Richard Wyatt

Getty Trust

Jerry Podany

Uta Barth

Tobey Moss

Katrin Henkel

Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives

Miko Charbonneau

Bruce Embrey

Hans Goto

Patrick Hayashi

Jean Hibino

Mitchell Higa

Roy Hirabayashi

Carolyn Iyoya Irving

Susan Kitazawa

Naomi Kubota Lee

Ron Kuramoto

Jennifer Mariko Neuwalder

Kimi Maru

Lori Matsumura

Alan Miyatake

Margret Mukai

Ruth Sasaki

Steven Shigeto Sindlinger

Masako Takahashi

Peggy Takahashi

Nancy Ukai

Hanako Wakatsuki-Chong

Rev. Michael Yoshii

Moore Foundation

Edward Penhoet

Kenneth Siebel

James C. Gaither

National Park Conservancy

Greg Moore

Sierra Club

Rhonda Anderson

Bruce Nilles

Verena Owen

Rita Harris

Resources and Planning

Anders Hauge

San Francisco Politics

Norman Yee

University History

Doris Sloan

Carolyn Merchant

Randy H. Katz

OHC Staff Top Moments of 2022

As another year draws to an end, the OHC team looks back on an eventful year. Here are some of top moments from 2022.

In June 2022, I helped plan and lead a session about university-community relations in the “Race and Power in Oral History Theory and Methodology” Symposium, of which the Oral History Center was a co-sponsor. This symposium was a great opportunity to hear from oral history practitioners from many fields as we move toward best practices for culturally responsive and anti-racist oral history. I was grateful to be a part of this work!

Also in June, I had the opportunity to co-interview D.C.-based artist Sylvia Snowden for the Getty Research Institute’s African American Art History Initiative. Being so close to some of Snowden’s large-scale, textured, and vibrantly-colored pieces was truly a highlight of my year.

I was also very pleased this year to partner with Shanna Farrell to produce a podcast called “Fifty Years of Save Mount Diablo,” based on our oral histories about Save Mount Diablo, an East Bay land conservation organization. Learn more here about this three-part podcast series on the OHC feed The Berkeley Remix.

-Amanda Tewes, Interviewer/Historian

The Oral History Center relies on a talented team of student editors and I’d like to use this opportunity to highlight their contributions. A big thank you to editors Mollie Appel-Turner, William Cooke, Adam Hagen, Shannon White, and Timothy Yue, and researcher/editor Serena Ingalls. The student editors serve critical functions in our oral history production, analyzing entire transcripts to write discursive tables of contents, entering interviewee comments, editing front matter, and writing abstracts. They do the work of professional editors and we would not be able to keep up our pace of interviews without them. Serena also conducts research for our social media outreach, maintains our editorial calendar, and suggests ideas for articles based on historical events. The student team has also helped me evaluate our process, training, and documentation, and provided invaluable suggestions in our department’s quest for continuous improvement. Excellent writers in their own right, the student employees also research and write articles featuring themes in our archive, which this year included Cal Athletics, the Cold War, urban development, and women in politics. These articles have enabled us to better share the wealth of our collection with scholars and the public. Please keep an eye out for their work in future editions of the newsletter.

–Jill Schlessinger, Communications Director/Managing Editor

2022 proved to be another exciting year at the Oral History Center. In April, we released the Chicana/o Studies Oral History Project. I started this project in 2017 with the aim of documenting the history and formation of Chicana/o Studies through in-depth interviews with the first generation of scholars who shaped it. Thanks to the generous support of universities throughout California and the West, the collection includes over a hundred hours of oral histories with the most prominent scholars in the field. You can read the project’s release article here.

Our work with State Archives on the California State Government Oral History Program also proceeded apace. In October, we celebrated the careers of Senators Loni Hancock, Lois Wolk, and Fran Pavley in an online an online event hosted by Secretary of State Shirley Weber, and publicly released their oral histories. I also had the amazing opportunity to conduct the oral history Bill Lockyer, documenting a forty-six-year career in California politics that included offices such as Senate Pro Tem, Attorney General, and State Treasurer.

Last year, we released the oral history of famed Yale Political Scientist James C. Scott, as well as affiliates of his Yale Agrarian Studies Program. I am thrilled to announce that this year we finished work on the OHC’s first, full-length documentary film featuring the life and career of James Scott. You can watch the film’s trailer here. The documentary will be released in Spring 2023.

Here’s to an even more eventful and exciting 2023!

-Todd Holmes, Interviewer/Historian

This has been a big year for me, both professionally and personally. I had the privilege of helping organize a “Race and Power in Oral History Theory and Methodology” Symposium, of which the Oral History Center was a co-sponsor. After months of planning, our committee brought together scholars and oral history practioners from around the country for three days of thoughtful, reflective, and inspiring conversation. I had the opportunity to interview people for several projects, including for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives, Anchor Brewing Company, the Getty Research Institute, the East Bay Regional Park District, and Save Mount Diablo. I co-producted a podcast celebrating the 50th anniversary of environmental conservation organization Save Mount Diablo with Amanda Tewes. I also became a mother, giving me a new perspective that I will bring to discussions of family and motherhood in my interviews. As ever, I grateful to be able to do this work, ask questions, and connect with the larger oral history community.

-Shanna Farrell, Interviewer/Historian

Three series of interviews in 2022 were especially memorable for me. First, fellow oral historians Shanna Farrell, Amanda Tewes, and I had the privilege to record over one hundred total hours of interviews with numerous narrators for the OHC’s new Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives (JAIN) oral history project. The JAIN project explores, preserves, and shares family narratives and traumatic legacies of the US government’s unjust confinement of Japanese Americans during World War II through oral histories with descendants of those who survived the race-based prison camps. The stories these narrators shared with us about the intersection of their family histories and their own experiences as Americans were both powerful and deeply personal.

Oral histories with three exceptional women—all exceptionally wise, accomplished, and active in environmental issues—were also among my most memorable moments from 2022. Doris Sloan helped stop a nuclear power plant from being built atop the San Andreas fault at Bodega Head and Harbor in the early 1960s, which later helped inspire her to return to school in her forties and earn an MS and PhD in geology and paleontology from UC Berkeley. Carolyn Merchant became a Distinguished Professor of Environmental History, Philosophy, and Ethics at UC Berkeley, where her research and writings over the past half century significantly influenced the fields of the History of Science, Women’s Studies, and Environmental History. And last summer, Mary Nichols and I finished recording an extensive 26-hour oral history of her life and storied career as an environmental lawyer and public servant, including her appointment as chair of the California Air Resources Board from 1979-1983 and again from 2007-2020, where she implemented vanguard regulations to make California a world leader in improving air quality and reducing emissions that cause climate change.

A third set of memorable interviews for me in 2022 was expanding the OHC’s long standing Sierra Club Oral History Project to record new climate and justice-focused narratives with three activists and organizers—Rhonda Anderson in Detroit, Verena Owen in Chicago, and Bruce Nilles in Oakland—all of whom worked on the Sierra Club’s transformational Beyond Coal campaign. Since its grassroots origins two decades ago, the Beyond Coal campaign stopped more than 200 new coal plants from being built across the United States and secured retirement of two-thirds of the nation’s existing coal plants. This work prevented untold tons of carbon emissions and other toxic pollution from poisoning our air, land, and water, and in doing so, it prevented tens of thousands of premature deaths in communities living near coal plants, often disinvested communities of color. In addition to its commitment to racial justice and grassroots power-building, the coal campaign supported a robust economic transition for coal communities at the state and national level, and it helped midwife our new era of clean energy solutions to further combat climate change.

Throughout 2022 and into this new year, it has been and remains my great honor at the Oral History Center to continue conducting inspired and intriguing interviews with such incredible narrators. I wish you and yours much love, peace, and power at the end of this year and throughout the next.

-Roger Eardley-Pryor, Interviewer/Historian

Virtual and in-person discussion on ethics in archiving

The UC Berkeley Oral History Center is proud to host a talk by oral historian Venkat Srinivasan, an alumnus of the 2014 Advanced Oral History Institute. Srinivasan invites us to imagine how we might construct a more inclusive, ethical, and accessible oral history archive.

Every archive accession brings with it questions about inclusivity, ethics and privacy. Please join the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library for a special guest presentation on ethics in the contemporary archive, by Venkat Srinivasan, archivist at the Archives at National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS) in Bangalore.

Tuesday, October 25, 11:30 a.m. – 1 p.m. Pacific Time.

In person in The Bancroft Library, Conference Room 267

Or join online via Zoom.

In his talk, “An Act of Imagination: The Archives as Commons,” Venkat Srinivasan—an alumnus of the Oral History Center’s Advanced Oral History Institute from 2014—invites us to imagine how we might construct a more inclusive, ethical, and accessible oral history archive. His presentation will address how questions of inclusivity, ethics and privacy are critical when an archive is just starting out, as is the case with the Archives at NCBS. Through examples from correspondence, oral histories, native digital files, its nascent accession and retention policies, and the challenge of a campus COVID-19 archive, this presentation will address the conflicts and synergies on rights to information, diversity, privacy, and the ethics of a contemporary archive.

The Archives at NCBS is a public collecting center for the history of science in contemporary India. It opened in 2019 and houses about 150,000 objects spread across 25 collections. The Archives at NCBS has one underlying philosophy: archives enable diverse stories. Through sharing the work that took place in 2020–21, this presentation will discuss four objectives for the archives: strengthening research collections and access in domain areas, pushing the frontiers of research in archival sciences, building capacity and public awareness through education, training and programming, and reimagining the archives as part of the commons. The Archives at NCBS is also part of Milli, a broader collective of individuals and communities interested in the nurturing of archives, and for the public to find, describe and share archival material and stories.

Speaker Biography

Venkat Srinivasan is the archivist at the Archives at NCBS in Bangalore. In addition, he currently serves on the institutional review boards for the archives at IIT Madras, ISI Kolkata, and NID Ahmedabad, and on the board of the Commission on Bibliography and Documentation of the IUHPST (International Union of History and Philosophy of Science and Technology). He is a member of the Encoded Archival Descriptions – Technical Sub-committee (Society of American Archivists), and Committee on the Archives of Science and Technology (CAST) of the ICA Section on Research Institutions (International Council on Archives). He is a life member of the Oral History Association of India (OHAI), and served in an executive role in OHAI between 2020 and 2022. He is a founding member of Milli, a collective of individuals and communities committed to the nurturing of archives. Prior to this, he was a research engineer at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford University. In addition, he is an independent science writer, with work in The Atlantic and Scientific American online, Nautilus, Aeon, Wired, and the Caravan. He graduated with a Masters in Materials Science from Stanford University (2005), a Masters in Journalism (science) from Columbia University (2009), and a Bachelors in Engineering from the University of Delhi (2003).

In-person directions and Zoom details

Zoom details

Please be sure to sign into a Zoom account (free, institutional, or paid).

Join Zoom Meeting

https://berkeley.zoom.us/j/97008598387

Meeting ID: 970 0859 8387

One tap mobile

+16699006833, 97008598387# US (San Jose)

In-person directions

Through the main entrance of The Bancroft Library, go straight. Once you pass the museum on your right, the Conference Room 267 is the first door on your left. This room is wheelchair accessible.

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. You can find all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history.

Oral History Release – Thomas Gaehtgens: Famed Art Historian and Director of the Getty Research Institute

“As a scholar, one’s career typically revolves around teaching, research, and scholarship. Once in a while, a scholar is lucky enough to have a hand in building something. I’d like to think I have helped build a thing or two in my career.”

Such were the words of renowned art historian Thomas Gaehtgens upon wrapping up his oral history at the Getty Research Institute (GRI) in the fall of 2017. That the words held an element of retirement was no coincidence. Gaehtgens had already enjoyed a long and successful academic career before assuming the directorship of the GRI in 2007, a position from which he would officially retire in the spring of 2018. True to form, Gaehtgens met retirement with the same productive stride that had underpinned his work throughout the previous five decades. Thus, after a fruitful delay, the Oral History Center and Getty Trust are pleased to announce the release of Thomas Gaehtgens: Fifty Years of Scholarship and Innovation in Art History, from the Free University in Berlin to the Getty Research Center.

Getty Research Center

For many in the academic and art world of Europe, Gaehtgens needs no introduction. Born in Leipzig, Germany, he completed his PhD in art history at the University of Bonn in 1966, and over the next forty years held professorships at the University of Göttingen and the Free University of Berlin. He is the author of nearly forty publications on French and German art, covering a wide range of topics and artists from the eighteenth to the twentieth century.

Scholarship aside, Gaehtgens also made a mark through his globalist approach to art, fostering relationships that bridged the divides between universities and museums, as well as those between nations. He organized the first major exhibition of American eighteenth and nineteenth century paintings in Germany, expanded the art history curriculum in Berlin to include non-Western areas, and founded the German Center for Art History in Paris. These efforts made him a natural fit for president of the Comité International d’Histoire de l’Art (CIHA), where he advanced initiatives such as the translation of art history literature and broadening the field of art history through international conferences.

Gaehtgens brought this same spirit of inclusivity and innovation to the Getty Research Institute. In many respects, he helped usher the GRI into the twenty-first century by launching a number of programs that not only brought modern technology to the study of art, but also two principles close to Gaehtgens’ heart: international collaboration and equal access for all. The creation of the Getty Provenance Index proved a case in point. In partnership with a host of European institutions, the Index provided a one-stop, digital archive for researchers to trace the ownership of various art pieces over the centuries. Here, for the first time, the records of British, French, Dutch, German, Italian, and Spanish inventories stood at the fingertips of researchers. These same principles of technology, cooperation, and equitable access also underpinned the GRI’s creation of the Getty Research Portal, a free online platform providing access to an extensive collection of digitized art history texts, rare books, and related literature from around the world. Other important achievements of Gaehtgens’ directorship included the Getty Research Journal, a more internationally represented Getty Scholars program, and the Getty’s California-focused art exhibitions, Pacific Standard Time.

Thomas Gaehtgens retired from the Getty Research Institute in 2018, officially ending an art history career that spanned over fifty years. Fittingly, his decades of work have been recognized around the world. He holds honorary doctorates from London’s Courtauld Institute of Art and Paris-Sorbonne University. In 2009, he received the Grand Prix de la Francophonie by the Académie française, an honor bestowed by the Canadian Government to those who contribute to the development of the French language throughout the world. And in 2011, Gaehtgens was elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Such honors highlight the indelible mark he left on the global field of art history, one still seen today from the German Center for Art History in Paris to the now-famed digital programs of the Getty Research Institute. Indeed, Thomas Gaehtgens was not just an influential teacher and productive scholar, but also an innovative art historian who helped build a thing or two.

You can access the full oral history transcript of Thomas Gaehtgens here. See also other oral histories from the Getty Trust Oral History Project.

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library has interviews on just about every topic imaginable. You can find the interview mentioned here and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. We preserve voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public.

Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

From the OHC Director: The Gift of Being an Interviewer

The Gift of Being an Interviewer

From years of listening, I’ve learned that we all want to tell our stories and that we want, we need, to be heard.

After close to nineteen years with the Oral History Center — ten of those years serving in a leadership role — I have decided to hang up my microphone and leave my job at Cal. As with any major life transition, reflections naturally pour forth at times like these. I’ve been keeping track of these thoughts in hopes that they might prove interesting to others who have spent so many hours interviewing people about their lives or those who are interested in oral history writ large.

For me, learning and practicing oral history interviewing has been a gift. It has made my life richer, allowed me to access insights about human nature that otherwise might have been hidden from me, and offered me the opportunity to see people as the individuals that they are, freed from the stifling confines of presumed identities and expected opinions.

At OHC, interviewers typically work on a wide variety of projects. We often interview about topics in which we do not already have expertise and thus must develop some fluency with something new to us. Because we contribute to an archive that is to serve the needs of an unforeseeable set of current and future researchers, we naturally interview people who have made their mark in very different fields. This means that we interview people, sometimes at tremendous length, who are not like us and whose life stories and ways of thinking might be very different from our own. There is a well-documented tendency among oral historians to interview our heroes, people whose political ideals jibe with our own, people who can serve protagonists in our histories, people whose voices we want to amplify. At the Oral History Center, this bias is not paramount — rather, we strive to interview people across a broad spectrum of every imaginable category. And while we almost always end up very much liking our interviewees, they need not be our personal heroes and are not required to share our opinions; they only need to be an expert in one thing: their own lives and experiences.

This way in which we do our work has sent me wide and far and exposed me to a profound diversity of ways of looking at the world. And this multiplicity of perspectives has informed, challenged, engaged, astounded, and, frankly, remade me again and again over the past two decades. It is this essential facet of my work that I consider a gift to my own life.

After having conducted approximately 200 oral histories, ranging in length from ninety minutes to over sixty hours each, I find it a tad difficult at this point to highlight some interviews and not others. Whenever I get asked (as I often do): what was your favorite interview? I used to wrack my brain, endlessly scrolling through all of those experiences, but now I usually just say, “my most recent oral history.” I offer that up because the latest one typically remains most fresh in my own (not always so robust) memory — it is the interview that still retains much of the nuance, content, and feeling for me and that’s why it is “the best.” Still, I want to offer up a few examples from some of my oral histories to show how interviewing has influenced the way I live in the world.

Moving beyond my comfort zone

I arrived at OHC in July 2003, first spending a year on a fellowship in which I was given the opportunity to finish my book manuscript, Contacts Desired (2006), and then in July 2004 I started as a staff interviewer. My areas of expertise were social history, the history of sexuality and gender, and the history of communications. My first major oral history assignment? A multiyear project on the history of the major integrated healthcare system, Kaiser Permanente. Not only was this topic well outside my area of expertise, it also was not intrinsically interesting to me. But this was a new job and a big opportunity, so with an imposing hill in front of me, I decided to climb it. The project went on for five years and during that time I conducted most of the four dozen interviews. The topics ranged from public policy and government regulation to epidemiological research and new approaches to care delivery. I was sensitive to my inexperience with the subject matter so I hit the books and consulted earlier oral histories. I worked hard to get up to speed.

Just a few interviews into the project I had what might be considered an epiphany. After years of studying historical topics that were familiar to me, even deeply personal, I was pleased to discover something new about myself: I loved the study of history and the process of learning something new. Period. With this newly understood drive, I pushed myself deeper into the project and, I hope, was able to be the kind of interviewer that allowed my interviewees to tell the stories that most needed to be told. As it happens, along the way, I learned a great deal about a topic — the US healthcare system — that is exceedingly important, extraordinarily complex, yet necessary to understand. When the push for healthcare reform burst through in 2009 and 2010, I felt informed enough to follow the story and to understand the possibilities and pitfalls endemic to such an effort. In short, if one is open to the challenge, oral history can significantly broaden one’s horizons, educating one in critical areas of knowledge (from the mouths of experts!), and it might even make one into a more informed citizen.

Questioning what I thought I already knew

The Freedom to Marry oral history project was in many ways the opposite of the Kaiser Permanente project. First off, I could rightfully consider myself an expert in the history of the fight to win the right to marry for same-sex couples and the broader issues surrounding it. After all, I had written a book on gay and lesbian history and had personal experience with the movement when I married my partner in February 2004. Moreover, in graduate school and in preparation for writing my book, I had closely studied the history of activism and social movements. I had gone into this project, then, thinking I had a pretty good idea of what the story would be and what the narrators might say on the topic: this would be another chapter in the decades-long fight for civil rights in which activists engaged in protest and direction action, spoke truth to power, and forced the recalcitrant and prejudiced to change their minds.

From fall 2015 through spring 2016, I conducted twenty-three interviews with movement leaders and big-name attorneys, but also with young organizers and social media pros; I interviewed people in San Francisco and New York, but also in Maine, Oklahoma, Minnesota, and Oregon. What I learned in these interviews not only made me greatly expand my understanding of the campaign for marriage equality, these interviews also forced me to revise my beliefs about social movements and how meaningful and lasting social change can happen (I write about this more here). As a result of this project, I came to believe that some forms of protest, especially violent direct action, are almost always counterproductive to the purported aims; that castigating people with different ideas and perceived values is wrong and likely to produce a long-term backlash; and that in spite of our differences of opinion on contemporary hot button social issues, the majority of people cherish similar core values — values that bind rather than separate. The interviews demonstrated that by focusing on the shared values, rather than hurling epithets like “homophobe!” or “racist!” at your opponents, the ground is better readied for future understanding to grow. The history I documented surely is more complex than this, but these observations are true to what I found and are a necessary part of the reason this particular movement succeeded as well as it did. Through the Freedom to Marry oral history project, I learned to question the accepted public narrative and even what historians think that they knew on a topic. I recognized that openness to new ideas is a prerequisite of good scholarship. I recognized that most of all I needed to listen to what the oral history interviewees said and to compare that to what I thought I already knew. As a result, I learned to not let what I thought I already knew determine what I could still learn.

Telling a good story

The oral history interview is a peculiar thing. As ubiquitous as interviewing seems today, from StoryCorps on NPR to countless podcasts featuring interviews around the world to articles in the biggest magazines, the classic oral history method as we practice it at OHC is still quite rare. For our interviews, both interviewer and interviewee put in a great deal of effort in terms of background research, drafting interview outlines, on-the-record interviewing (often in excess of 20 hours with one person), and review and editing of the interview transcript. As a result, our interviews are almost always excellent source material for historians, journalists, and researchers and students of all stripes. But what moves an oral history from “good documentation” to something more is often the quality of the storytelling. Certainly some people, as a result of special experiences, have more fascinating stories to tell than others, but everyone I’ve ever interviewed has many worthwhile stories to tell: from formative family dynamics while young to the universal process of aging.

The difference between a competently told story and an engrossing one isn’t necessarily the elements of the story but the skill and verve of the storyteller. To hear Richard Mooradian, for example, speak about his life as a tow truck driver on the Bay Bridge and tell what it’s like to tow a big rig on the bridge amidst a driving rain storm is, yes, to learn something new but, more, it is to gain insight into a personality and the passion that drives that person to do what he does. I eventually learned (maybe I’m still learning) that when someone begins a story — and I know now the difference between a question being answered and a story being told — it is time for me to shut up, actively listen, and be open to the interviewee to reveal something meaningful about themselves. After years of helping, I hope, others give the best telling of their own stories, I started to think about my own stories, both the stories themselves but also how they have been told. I’ve come to think that these stories are nothing less than life itself: they are the emotional diaries that we keep with us always and, if we’re good, are prepared to present them to friends and strangers alike. From years of listening, I’ve learned that most of us want to tell our stories and that we want, we need, to be heard. This is a deeply humane impulse and I like to think that nurturing this impulse is at the core of what I’ve learned to be of true value over the past two decades.

These three lessons — openness to moving beyond your comfort zone, questioning what you think you already know, and telling a good story — are not necessarily profound or new. For me, however, they are real and as I return to them regularly in my work and personal life, they have been transformative. They have been a gift. The world of knowledge is massive. Learning something new is a key part of this gift. I’ve long recognized that we live in a world of Weberian “iron cages,” siloed into separate tribes. Listening to my interviewees challenge accepted wisdom inspired me to buck trends, forget the metanarratives, and break free from those cages confining our intellect and spirit. Stories are the most precious things we can possess. Create many of your own and share them widely – and wildly. After close to nineteen years at the Oral History Center, I am departing to do just that: to focus on living new stories and ever striving to tell them better.

Martin Meeker

Oral History Center

Director (2016-2021)

Acting Associate Director (2012-2016)

Interviewer/Historian (2004-2012)

Postdoc (2003-2004)

Presenting the Oral History Center Class of 2020

At the conclusion of every academic year, the Oral History Center staff takes a moment to pause, reflect on the interviews completed over the previous year, and offer gratitude to those individuals who volunteered to be interviewed. The names below constitute the Oral History Class of 2020. Please join us in offering heartfelt thanks and congratulations for their contributions!

We would also like to take this time to thank our student employees, undergraduate research apprentices, and library interns. It was a unique semester, topping off a busy and productive year, and they continued to come through for us, as they always do. We rely on this team for work that is critical to our operations: research, interview support, and curriculum development; video editing; writing and editing of abstracts, front matter, and transcripts; and more. They’ve even produced articles and oral history performances to share our work with wider audiences. We couldn’t do it without them!

Find these and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

The Oral History Center Class of 2020

Individual Interviews

Robert L. Allen

Bruce Ames

Samuel Barondes

Alexis T. Bell

Robert Birgeneau

John Briscoe

Willie Brown

George Miller

Michael R. Peevey

Nancy Donnelly Praetzel

Robert Praetzel

John Prausnitz

Zack Wasserman

Bay Area Women in Politics

Mary Hughes

California State Archives

Jerry Brown

Chicano/a Studies

Vicki L. Ruiz

East Bay Regional Park District

Glenn Adams

Ron Batteate

Kathy Gleason

Raili Glenn

Brian Holt

Diane Lando

Mary Lentzner

John Lytle

Beverly Marshall

Rev. Diana McDaniel

Roy Peach

Janet Wright

Economist Life Stories

George Tolley

Getty Trust

Peter Bradley

Kathleen Dardes

David Driskell

Melvin Edwards

Charles Gaines

Kenneth Hamma

Thomas Kren

David Lamelas

Mark Leonard

Richard Mayhew

Howardena Pindell

Michael R. Schilling

Joyce Hill Stoner

Yvonne Szafran

Global Mining

Bob Kendrick

Napa Valley Vintners

David Duncan

Paula Kornell

David Pearson

Linda Reiff

Emma Swain

SF Opera

Kip Cranna

David Gockley

Sierra Club

Lawrence Downing

Aaron Mair

Anthony Ruckel

SLATE

Susan Griffin

Julianne Morris

Yale Agrarian Studies

Marvel “Kay” Mansfield

Alan Mikail

Paul Sabin

Ian Shapiro

Helen F. Siu

Elisabeth Jean Wood

Thank You

Student Employees

Max Afifi

Gurshaant Bassi

Yarelly Bonilla-Leon

Jordan Harris

Abigail Jaquez

Nidah Khalid

Ashley Sangyou Kim

Devin Lizardi

JD Mireles

Tasnima Naoshin

Lydia Qu

Lauren Sheehan-Clark

Librarian Interns

Jennifer Burkhard

Charissa Fitzpatrick

Undergraduate Research Apprentices

Corina (Mei) Chen

Nika Esmailizadeh

Evgenia Galstyan

Emily Keats

Esther Khan

Emily Lempko

Atmika Pai

Samantha Ready

Kendall Stevens

Episode 3 of the Oral History Center’s Special Season of the “Berkeley Remix” Podcast

Lately, things have been challenging and uncertain. We’re enduring an order to shelter-in-place, trying to read the news, but not too much, and prioritize self-care. Like many of you, we here at the Oral History Center are in need of some relief.

So, we’d like to provide you with some. Episodes in this series, which we’re calling “Coronavirus Relief,” may sound different from those we’ve produced in the past, that tell narrative stories drawing from our collection of oral histories. But like many of you, we, too, are in need of a break.

The Berkeley Remix, a podcast from the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. Founded in 1954, the Center records and preserves the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world.

We’ll be adding some new episodes in this Coronavirus Relief series with stories from the field, things that have been on our mind, interviews that have been helping us get through, and finding small moments of happiness.

Our third episode is from Amanda Tewes.

Greetings, everyone. This is Amanda Tewes.

As we are all still hunkering down at home, I wanted to share with you a few selections from Robert Putnam’s classic book, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Now, I can’t say that this book is a personal favorite of mine – in fact, it brings up some not-so-fun memories of cramming for my doctoral exams in American history – but it has been on my mind lately, especially in thinking about our shifting social obligations to one another in times of crisis, like the 1918 Influenza Epidemic or the heady days after 9/11.

Putnam published Bowling Alone in 2000, following decades of what he saw as degenerating American social connections, and much of the book reads like a lament of a changing American character.

In the context of our current moment, the following passages stood out to me:

……………………………………………………………………………………………………….

The Charity League of Dallas had met every Friday morning for fifty-seven years to sew, knit, and visit, but on April 30, 1999, they held their last meeting; the average age of the group had risen to eighty, the last new member had joined two years earlier, and president Pat Dilbeck said ruefully, “I feel like this is a sinking ship.” Precisely three days later and 1,200 miles to the northeast, the Vassar alumnae of Washington, D.C., closed down their fifty-first – and last – annual book sale. Even though they aimed to sell more than one hundred thousand books to benefit college scholarship in the 1999 event, co-chair Alix Myerson explained, the volunteers who ran the program “are in their sixties, seventies, and eighties. They’re dying, and they’re not replaceable.” Meanwhile, as Tewksbury Memorial High School (TMHS), just north of Boston, opened in the fall of 1999, forty brand-new royal blue uniforms newly purchased for the marching band remained in storage, since only four students signed up to play. Roger Whittlesey, TMHS band director, recalled that twenty years earlier the band numbered more than eighty, but participation had waned ever since. Somehow in the last several decades of the twentieth century all these community groups and tens of thousands like them across America began to fade.

It wasn’t so much that old members dropped out – at least not any more rapidly than age and the accidents of life had always meant. But community organizations were no longer continuously revitalized, as they had been in the past, by freshets of new members. Organizational leaders were flummoxed. For years they assumed that their problem must have local roots or at least that it was peculiar to their organization, so they commissioned dozens of studies to recommend reforms. The slowdown was puzzling because for as long as anyone could remember, membership rolls and activity lists had lengthened steadily.

In the 1960s, in fact, community groups across America had seemed to stand on the threshold of a new era of expanded involvement. Except for the civic drought induced by the Great Depression, their activity had shot up year after year, cultivated by assiduous civic gardeners and watered by increasing affluence and education. Each annual report registered rising membership. Churches and synagogues were packed, as more Americans worshipped together than only a few decades earlier, perhaps more than ever in American history.

Moreover, Americans seemed to have time on their hands. A 1958 study under the auspices of the newly inaugurated Center for the Study of Leisure at the University of Chicago fretted that “the most dangerous threat hanging over American society is the threat of leisure,” a startling claim in the decade in which the Soviets got the bomb. Life magazine echoed the warning about the new challenge of free time: “Americans now face a glut of leisure,” ran a headline in February 1964. “The task ahead: how to take life easy.” …

…For the first two-thirds of the twentieth century a powerful tide bore Americans into ever deeper engagement in the life of their communities, but a few decades ago – silently, without warning – that tide reversed and we were overtaken by a treacherous rip current. Without at first noticing, we have been pulled apart from one another and from our communities over the last third of the century.

Before October 29, 1997, John Lambert and Andy Boschma knew each other only through their local bowling league at the Ypsi-Arbor Lanes in Ypsilanti, Michigan. Lambert, a sixty-four-year-old retired employee of the University of Michigan hospital, had been on a kidney transplant waiting list for three years when Boschma, a thirty-three-year-old accountant, learned casually of Lambert’s need and unexpectedly approached him to offer to donate one of his own kidneys.

“Andy saw something in me that others didn’t,” said Lambert. “When we were in the hospital Andy said to me, ‘John, I really like you and have a lot of respect for you. I wouldn’t hesitate to do this all over again.’ I got choked up.” Boschma returned the feeling: “I obviously feel a kinship [with Lambert]. I cared about him before, but now I’m really rooting for him.” This moving story speaks for itself, but the photograph that accompanied this report in the Ann Arbor News reveals that in addition to their differences in profession and generation, Boschma is white and Lambert is African American. That they bowled together made all the difference. In small ways like this – and in larger ways, too – we Americans need to reconnect with one another. That is the simple argument of this book.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………….

There is a lot to find discouraging these days, but I actually have been heartened to see the ways in which Americans – and individuals the world over – have been committing and recommitting to each other and to their communities. Citing a “now more than ever” argument, folks are setting up local pop-up pantries with food, household supplies, and books; some are reaching out to their neighbors for the first time; and of course, we are practicing social distancing not just to keep ourselves safe, but also our communities.

Witnessing these acts, I have to wonder if Putnam’s argument about a decline in social obligations and connectivity was just one moment in American history and not a full picture. What will the historical narrative about this time be? Are we now experiencing a blip in social relations, or is this a great turning point? I’m hoping for the latter.

Stay safe, everyone. Until next time!

Dispatch from the OHC Director, April 2020

From the OHC Director, April 2020

I’ve been thinking a great deal of late about what it means to live a life connected or disconnected or perhaps something in between. I suspect I’m not alone in pondering these states of being — a kind of remote engagement that itself feels a little bit like connection.

Oral history is about many things: listening, documenting, questioning, recording, explaining. I think connection is always key to the work that we do as oral historians. But like many other operations, including basically all non-medical research projects that involve humans, our work conducting interviews is largely shut-down while we consider how best to forge ahead.

My colleagues and I have always valued the importance of the in-person, face-to-face interviewing experience. We regularly travel across the country at some considerable expense just so we can be in the same room with the person we are interviewing. We have found this time in close proximity with our narrators to be priceless. Not only does this allow us to shake hands, look eye-to-eye, and gauge body language just before and during the interview, but also these are practices that, until recently, have been second nature — we usually do them without thinking much about it. There really is an unconscious kind of dance that happens, especially when meeting someone for the first time, that in most instances results in a spontaneously choreographed fluidity that can carry the ensuring interview through fond memories and bad. Because of this, up to this point, only when it really was impossible to meet in person have we conducted an interview over the phone or online.

But times change. The current health crisis has profoundly rearranged social relationships, and likely for some time into the future. (Dr. Fauci even suggested that we rethink the practice of shaking hands, which, I’ll admit, makes me sad.) The Oral History Center staff have been scattered now for over a month. But we have endeavored to not lose touch with one another. Thanks to multifarious technological options, we have easily transitioned our weekly staff meetings online. We use either Google Hangouts or Zoom and, so far, everyone has used video, so we get to hear each other’s voices and see faces too. We sometimes have agenda items that require lengthy discussion, at other times we simply check in with each other about work but also about “how things are going.” We live in different settings so people have different challenges and we do our best to touch on those. I also chat every week with each of my colleagues individually and I’m very pleased to know that my colleagues have been meeting with each other, doing their best to push projects forward. The success of these virtual meetings, and, well, the zeitgeist, inspired me to set up virtual happy hours with friends and family. My family lives across the country and it’s been probably four years since we’ve been in the same room together but for the past two weeks we’ve all gathered online to check in, tell stories, have some laughs, get serious and, of course, get photobombed by various kids and dogs. We don’t escape the underlying gravity of the current situation, but this hasn’t stopped connection — in some real ways it has promoted it.

So, with this in mind, we are exploring the options for bringing our oral history back to life by bringing it online. We’re currently testing out various options for video and audio recording, paying close attention to everything from quality of recording to ease of use (considering that most people we interview don’t fit within the “digital native” demographic). We also are sensitive to the dimension of personal connection, rapport, and understanding, but given recent experiences “at” home and “in” the office, we have reason to be optimistic. The reasons for going online are not only about opportunity, they are much deeper and in some ways quite profound: every day, every month that passes, we lose an opportunity to interview someone who should have had the opportunity to tell their story. In fact, we just learned the very sad news that artist and advocate of Black artists, David Driskell, passed away due to complications from COVID-19. This was a man with a story to be told — and thankfully, with our partners at the Getty Trust, we conducted his oral history last year. We simply cannot wait out this epidemic and let it steal stories along with lives.

The second profound reason is related to something I’ve mentioned rather delicately here in the past: that the Oral History Center is a soft-money institution. What that means is we are basically a non-profit that earns its money (allowing us to do our work) by conducting interviews. The longer we are prevented from conducting oral histories, the more precarious our position becomes. We hope for but do not anticipate relief from the university, the state, or the federal government. All we want is to resume the good work of documenting our shared and individual experiences in times of growth and times of challenge — to continue the work that we’ve done for the past 66 years.

As we consider the path ahead, the Oral History Center staff continues to work vigorously albeit remotely. We’re finishing the production process on dozens of interviews that have been conducted already — that is, writing tables of contents, working with narrators on edits for accuracy and clarity, creating the final transcripts for bound volumes and open access on our websites. We continue to process original audio and video recordings so that they can be uploaded to our online oral history viewer. We’re writing blog posts about oral history and producing podcasts, including our newest and very topical season, Coronavirus Relief. Plus in addition to the regular work, we’re using this opportunity to focus on long desired projects: We’re creating curriculum for high schools; we’re writing abstracts for old interviews that never had them; and we’re using this time to think about new projects and write grant proposals so that when the time comes, we’ll be ready to go full steam ahead.

Check back here next month for more on our efforts to move oral history online. We’ll share our results publicly as many others are venturing into this domain too — and have themselves made important contributions to the conversation (I especially recommend checking out the free Baylor / OHA webinar on “Oral History at a Distance”). Until then, we sincerely hope that everyone this newsletter reaches stays safe, healthy, and able to remain connected to those who are important to you.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library