Author: Roger Eardley-Pryor

Oral History Center Presents Work at NCPH in Utah and Explores “Belonging” in Japanese American History

In April 2024, Oral History Center (OHC) interviewers Amanda Tewes, Shanna Farrell, and Roger Eardley-Pryor traveled to Salt Lake City, Utah, where we presented our work on the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project at the annual meeting of the National Council on Public History (NCPH). We also joined a pilgrimage to the central desert of Utah along with other public historians and several members of the Wakasa Memorial Committee, including survivors and descendants of the Topaz prison camp in Utah, one of the ten US government mass incarceration sites where Japanese Americans were unjustly imprisoned during World War II. Our experiences in Utah at NCPH and at Topaz reiterated how history remains a powerful and living force, and how oral history can help promote that power. Difficult questions about “belonging” appear throughout many of the oral histories in OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives project, and those same questions punctuated much of our time in Utah this past April.

“Historical Urgency” was the conference theme for this year’s meeting of the National Council on Public History (NCPH) in Salt Lake City, where some 740 attendees presented, networked, and learned together. Presentation topics included community engagement, particularly with communities whose histories face urgent existential threats; communicating the critical importance of history and historical thinking; discourse and dialogue in a time of extreme social polarization; exploration of oral history, especially the collection of oral histories from older generations; and repatriation of human remains and cultural objects. As noted by NCPH president Kristine Navarro-McElhaney, conference discussions highlighted how historians’ work for public audiences remains essential to the fabric of our society, especially during this time of political and cultural polarization—and yet historical perspectives, tools, and history workers themselves have increasingly come under threat. While urgency may seem in opposition to the often slow and deliberate work that oral historians and other public historians do to build trust and lasting relationships with the communities we serve, many of us cannot help but feel a strong sense of urgency and importance in our efforts to collaboratively excavate the past and elevate community stories in ways that help make meaning in the present.

We felt especially honored to share at this NCPH our work on the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project. Our roundtable presentation recounted the project’s origins, the trauma-informed interviewing approach we used with these oral histories, and some of emergent themes from the project’s interviews, like “belonging,” “art and expression,” “healing,” and “memorialization.” The roundtable’s discussion was moderated by Hanako Wakatsuki-Chong, the Executive Director of the Japanese American Museum of Oregon and a former National Park Service Ranger who recorded her own oral history as part of the project. Nancy Ukai and Masako Takahashi, both of whom also recorded oral histories as part of the project, attended and also presented at the NCPH conference in Utah, where they heard portions their own oral history interviews during our presentation. Our presentation included audio clips from season 8 of The Berkeley Remix podcast, “From Generation to Generation”: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration,” as well as graphic narrative artwork by Emily Ehlen, all based on oral histories recorded for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project.

Relatedly, during the NCPH conference, I (Roger Eardley-Pryor) joined other public historians for a tour of the Utah Museum of Fine Arts on the University of Utah campus to see a new exhibit titled Pictures of Belonging: Miki Hayakawa, Hisako Hibi, and Miné Okubo. The exhibition was curated by Professor ShiPu Wang of UC Merced and features over 100 paintings and works on paper by these three Japanese American women artists, all critically acclaimed with long and productive careers. Yet during World War II, both Hibi and Okubo were unjustly incarcerated in Utah at Topaz, along with Hayakawa’s parents. Pictures of Belonging follows the three artists’ prewar, wartime, and postwar art practices, sharing an expanded view of the American experience by women who used artmaking to take up space, make their presence and existence visible, and assert their own belonging. Many of the exhibit’s artworks are on view to the public for the first time. The exhibit’s titular theme of “belonging” resonated nicely with the Oral History Center’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project at UC Berkeley, and Okubo even earned her Master in Fine Arts degree in 1938 from UC Berkeley. Our tour of the art exhibit was co-led by Sarah Palmer, Head Exhibition Designer at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, and by Dr. Kristen Hayashi, Director of Collections Management & Access and Curator at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles. I am especially grateful I could tour Pictures of Belonging with Masako Takashashi, who herself is an outstanding multi-media artist, was born behind barbed wire at the Topaz prison camp in Utah, and who I worked with to record her forthcoming oral history interview for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project.

Our visit to the Utah Museum of Fine Arts also included another new exhibit titled Chiura Obata: Layer by Layer, which presents an in-depth look at the creation and conservation of Obata’s beautiful “Horses” silk screen painting from 1932. Chiura Obata was an esteemed artist and professor at UC Berkeley who was also incarcerated during World War II at Topaz in Utah, where he and Miné Okubo taught art classes for their fellow Japanese American incarcerees. Kimi Kodani Hill, the granddaughter of Chiura Obata, recently presented at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts on her grandfather’s life and work, and I’m grateful that during our recent meeting in Berkeley, prior to my own Utah trip, she shared stories with me about Obata’s silk screen exhibit. During the screen’s 2022 conservation treatment, conservators at Nishio Conservation Studio discovered that the four-paneled screen contained hidden full-scale preparatory charcoal drawings of the horses. In addition, they found that the screen’s internal layers were made of practice drawings by Professor Obata and his summer 1932 students. The recently conserved screen, the full-scale under-drawings, and a selection of the practice drawings were all on display at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, along with a short film on the conservation process, which itself is an artform. After we returned to the Bay Area, Kimi Kodani Hill provided a guided tour of another exhibition with forty of Chiura Obata’s watercolors, woodblock prints, and ink paintings from several decades of his life that are currently displayed through mid-July at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

On April 11, 2024, in Salt Lake City at the NCPH conference, Masako Takahashi and Nancy Ukai joined other members of the Wakasa Memorial Committee to present their own panel titled “Who Writes Our History?” This panel explored the life and tragic death of James Hatsuaki Wakasa, who was shot and killed while confined in Topaz eighty-one years earlier on April 11, 1943. Their panel also addressed urgent and ongoing challenges over descendant and survivor community consent and collaboration with the Topaz Museum following the recent discovery and excavation of the Wakasa Memorial Stone from the Topaz incarceration site in 2021. That massive, 1,000-pound stone memorial was erected in 1943 by Japanese American incarcerees at Topaz just after James Wakasa’s murder there. But US government authorities quickly demanded the memorial’s destruction in their effort to bury acknowledgement of Wakasa’s death from a bullet fired by a white, nineteen-year-old US soldier who was quickly acquitted of any crime. The Wakasa Memorial Committee’s NCPH presentation, which was standing-room only, featured short films and personal reflections on the life, death, memory, and now-contested stone memorial of James Wakasa.

Two days later, still in Utah, Oral History Center interviewers and several other public historians joined Ukai, Takahashi, and other members of the Wakasa Memorial Committee on a pilgrimage to the dust-strewn ruins of the Topaz site on the edge of the Great Basin in Utah’s central desert. The bus ride out to the remote site included watching historical films and sharing personal backgrounds and reflections amongst this group that had assembled from eight different states. Hours later, we arrived at a sparse, sun-bleached landscape encircled by distant snow-capped mountains. Much of the original barbed wire fence around Topaz remains today where some 8,000 Americans were unjustly imprisoned for years during World War II. Crumbled concrete foundations mark sites of now-gone guard towers where US soldiers aimed their guns down at the Japanese American prisoners, and from where they occasionally fired shots, like the one that pierced James Wakasa’s heart in 1943. At the Topaz site, we joined members of the Topaz Museum Board, including board president Patricia Wakida; Scott Bassett, board secretary and education director at the Topaz Museum; and Topaz descendant and board member Dianne Fukami. Together, we all participated in a ceremony organized by the Wakasa Memorial Committee to commemorate Wakasa’s death, as well as the 140 people who died behind barbed wire at Topaz, and the sixteen Japanese American soldiers drafted from Topaz who died during their World War II military service.

The Wakasa 81st Memorial Ceremony at Topaz began at block 36-7-D, where James Wakasa’s tar-paper barracks once stood. From there, we re-traced Wakasa’s steps across the dusty and now-hauntingly empty landscape to the western perimeter site of his murder, near where the Wakasa Memorial Stone once stood before incarcerated Japanese Americans, under government orders to destroy the memorial, buried it in 1943. An artist’s large recreation of the stone, this one blazing white and made of paper mache and wood, stood near the former burial site of the stone memorial before its removal in 2021. After a land blessing and words of remembrance from survivors born at Topaz, we encircled the artist’s stand-in memorial with name tags bearing the names of our own ancestors. Joshua Shimizu then sang in both Japanese and English the hymn “Rock of Ages,” which was also sung at Wakasa’s funeral in April 1943, and which offered deeper meaning for the missing original Wakasa Memorial Stone.

During the “Rock of Ages” hymn, ceremonial participants attached to the base of the art installation many colorful paper flowers that carried tags naming other Japanese Americans who died in Topaz. The paper flowers we carried to the ceremony were made by Topaz survivors and descendants in honor of the paper floral blossoms folded by imprisoned Japanese Americans at Topaz in lieu of actual flowers for James Wakasa’s 1943 funeral. Miné Okubo, the artist whose work we saw earlier at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, drew several illustrations of Wakasa’s funeral while she was incarcerated at Topaz, including drawings of imprisoned women folding paper flowers to adorn wreaths and crosses. On the desert floor in April 2024, white paper flowers also surrounded the excavation site where the Topaz Museum Board excavated Wakasa’s Memorial Stone in 2021. The Wakasa 81st Memorial Ceremony at Topaz simultaneously evoked absence and living memory. It was especially meaningful to me (Roger) to join Nancy Ukai and Masako Takahashi at the ceremony after having worked together to record their oral histories, in which they shared intergenerational memories about James Wakasa and more recent memories about the Wakasa Memorial Stone’s recent rediscovery and removal from that site.

After the ceremony at Topaz, the pilgrimage group boarded the bus and traveled sixteen miles to the handsome Topaz Museum, which opened in 2017 after decades of fundraising and planning in the small town of Delta, Utah. Once there, the pilgrimage group found their way to the back of the museum where we gathered to witness the actual Wakasa Memorial Stone, a one-thousand-pound rock now confined in a small enclosure. After paying our respects to the stone, we toured the Topaz Museum’s exhibits and collections, which include hundreds of artifacts, photographs, and oral histories, as well as 150 pieces of original artwork. The Topaz Museum’s core exhibit explores the complex story of the World War II Japanese American incarceration experience, especially as it transpired at Topaz. The exhibit begins with the racist laws that marginalized early Japanese immigrants, which lead eventually to the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. The exhibit extends into the traumatic impacts of their exile, with an obvious focus on the Topaz experience, and it concludes with an examination of the Constitutional violations that the incarcerees were forced to endure. I found the Topaz Museum exhibits to be impressive, interactive, and informative. The pilgrimage group then gathered a final time out back by the Wakasa Memorial Stone before boarding the bus and returning to Salt Lake City.

The emotional experiences throughout our time in Utah reminded me of William Faulkner’s line in Requiem for a Nun: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” The public history presentations on “historical urgency” at NCPH, the outstanding exhibits on Japanese American artists, the powerful pilgrimage to Topaz and the commemorative ceremony at the site of James Wakasa’s murder, which we shared with survivors and descendants of the prison camp eighty-one years from the date of Wakasa’s death, as well as our trip to the Topaz Museum to see its exhibits and the excavated Wakasa Memorial Stone all reminded us that history is still very much alive and shapes our present experiences. At both the Topaz incarceration site and at the Topaz Museum in Delta, we witnessed some of the still-simmering tensions between Topaz Museum Board members and members of the Wakasa Memorial Committee over what has happened and what will happen to the now-unearthed Wakasa Memorial Stone. Throughout all of those experiences in Utah, I kept thinking on the recurrent theme of “belonging,” including in the oral histories we continue to conduct in the Oral History Center’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project. “Belonging” carries multiple meanings and invites complex questions. Within what communities, or within which factions of communities, do we find and feel belonging? Throughout history, and up through the present, where have Japanese Americans found belonging? What about the physical artifacts of Japanese American history, like artwork created during World War II-era incarceration, or like the recently re-discovered Wakasa Memorial Stone? To whom do those objects belong? And importantly, who has the right to tell the history of artifacts, artwork, memorials, or lived experiences? To whom does this history belong?

Answers to questions of belonging are elusive because they’re always evolving. I do know, however, how grateful I feel to continue working with individuals and communities to record oral histories that empower narrators to share their own living memories and reflections on the past, and how the personal histories these interviews record will continue to shape our shared present moments. These experiences in Utah helped further inspire our ongoing work on the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project. We hope that you, too, can find inspiration and meaning in these stories, and that they might inform your own sense of belonging.

— Roger Eardley-Pryor, Oral History Center historian and interviewer

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. While we receive modest institutional support, we are a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. We must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

Graphic Narrative Art by Emily Ehlen from OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project

Below are ten graphic narrative illustrations created by artist Emily Ehlen that she drew from stories and themes in the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, or JAIN project, recorded by the Oral History Center, or OHC.

The OHC’s JAIN project documents and disseminates the ways in which intergenerational trauma and healing occurred after the United States government’s mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. The OHC team interviewed twenty-three Japanese American survivors and descendants of the World War II incarceration to investigate the impacts of healing and trauma, how this informs collective memory, and how these narratives change across generations. Initial interviews in the JAIN project focused on the Manzanar and Topaz prison camps in California and Utah, respectively. The JAIN project began at the OHC in 2021 with funding from the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant. The grant provided for 100 hours of new oral history interviews, as well as funding for a new season of The Berkeley Remix podcast and for Emily Ehlen’s unique artwork below, all based on the JAIN project oral histories.

We encourage you to use and share Emily Ehlen’s artwork, along with the JAIN project oral history interviews, especially in classrooms when teaching the history and legacy of the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. When using these images, please credit Emily Ehlen as the artist (for example, Fig. 1, Ehlen, Emily, WAVE, digital art, 2023, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley), and see the OHC website for more on permissions when using our oral histories. To save a digital copy of any illustration below for fair use, right click on the image and select “Save Image As…” The text description that accompanies each illustration below aims to provide accessibility for the visually impaired in lieu of Alt-Text limitations, which does not easily accommodate graphic narrative images. In a separate blog post, you can learn more about the artist Emily Ehlen and her processes while creating these dynamic illustrations drawn from the memories and reflections of JAIN oral history narrators.

Artist’s statement

Emily Ehlen’s illustrations for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project convey compelling narratives and imagery, with impactful shapes and color, by crafting traditionally and translating images into digital pieces. She uses text and imagery to balance the composition and support storytelling elements. Her work encompasses themes of identity and belonging, intergenerational connections, and healing. The collection navigates the impact and experiences of Japanese American incarceration during World War II and its effects on future generations.

WAVE by Emily Ehlen

This image titled WAVE consists of two panels. The top panel depicts text that relates to the number of generations of Japanese descents surrounding a family portrait using barbed wires as arrows. The text is in romanized Japanese and kanji. It reads: “Issei,” meaning first generation; “Nisei,” meaning second generation; “Sansei,” meaning third generation; “Yonsei,” meaning fourth generation; and “Gosei,” meaning fifth generation. The bottom panel depicts a large wave and guard tower behind barbed wire with text above that reads, “Your generation is just one part of the wave, and you do your best to build what you can for the next generation in your family.”

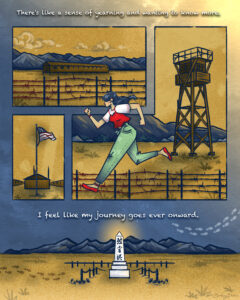

MANZANAR by Emily Ehlen

This image titled MANZANAR consists of four different panels. Each panel depicts a part of an incarceration camp and features barbed wire, the American flag, and the buildings in the camp. Above the top panel there is text that reads, “There’s like a sense of yearning and wanting to know more.” In the middle right panel, a woman in a red top layered over a white T-shirt and green pants runs towards the left of the image. The bottom panel depicts the cemetery monument at Manzanar National Historic Site, with Japanese kanji written on top, which reads, “I REI TO,” or “soul consoling tower.” Below the bottom panel there is text that reads, “I feel like my journey goes ever onward.”

STORIES by Emily Ehlen

This image titled STORIES consists of four panels. The top panel depicts a growing boy talking to his mother. An incarceration camp appears behind the mother. Above this top panel, the text reads, “My mom would not speak of things in camp. Maybe she didn’t want to or couldn’t at the time. It wasn’t ’til I was older did she begin telling me stories of camp.” Under this top panel, the text reads, “I got to know more about my mom, about a part of her life when I wasn’t there.” Two middle panels follow, depicting a green puzzle piece and crying eyes behind barbed wire. The text between these panels reads, “The missing piece she kept. The sadness she concealed.” In the bottom panel, tears from the eyes above fall into a plant on the ground that is growing. The text on this panel reads, “Talking about it didn’t make the pain disappear, but letting her experiences come to light brought a place for healing.”

TEACHER by Emily Ehlen

This image titled TEACHER consists of four panels. The top left panel shows a male teacher next to a chalkboard. The text on the chalkboard reads, “In middle school, we were learning about the Holocaust, and our teacher was telling the whole class like, ‘Well, Jewish people were put in camps…'” The top right panel depicts a raised hand with text that reads, “And I was like, ‘Wait, my grandmother was put in a camp.’ So I raised my hand.” The middle panel depicts a girl sitting at a desk, a male teacher standing, and a large crack between them. On the left of the panel, the girl says, “My grandparents were put in a camp, but they were put in a camp by America.” The text in the large crack reads, “And there was this awkward silence.” The teacher responds, “Well, we didn’t kill people.” The word “kill” has a red strikethrough on it. The bottom panel depicts the girl at the desk alone in the dark. The text reads, “I remember that as the first time I felt like my experience was disparaged or put down, but I was too young to really understand that.” Text on the bottom left indicates these quotations are from Miko Charbonneau’s oral history for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

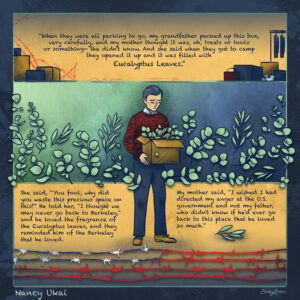

EUCALYPTUS by Emily Ehlen

This image titled EUCALYPTUS consists of three panels. The top panel depicts suitcases and boxes of various sizes, and includes text which reads, “When they were all packing to go, my grandfather packed up this box, very carefully, and my mother thought it was, oh, treats or tools, or something—she didn’t know. And she said when they got to camp and opened it up and it was filled with Eucalyptus Leaves.” The words “eucalyptus leaves” are larger than the other words. In the center, the grandfather stands in front of all of the panels with a box of eucalyptus leaves. He is looking down with a sad expression. The bottom panel depicts some eucalyptus leaves as well as barbed wire that mimics the red, white, and blue of an American flag. This panel includes text which reads, “She said, ‘You fool, why did you waste this precious space on this?’ He told her, ‘I thought we may never go back to Berkeley,’ and he loved the fragrance of the Eucalyptus leaves, and they reminded him of the Berkeley he loved. My mother said, ‘I wished I had directed my anger at the U.S. government and not my father, who didn’t know if he’d ever go back to this place that he loved so much.'” Text on the bottom left indicates these quotations are from Nancy Ukai’s oral history for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

SPLASH by Emily Ehlen

This image titled SPLASH consists of two panels on the top and two on the bottom. The top left panel depicts a younger woman and an older woman in a boat. Text above the top two panels reads, “The U.S. Government told my mother, ‘It is advisable that you move as far away from California as you can. Stay away from other Japanese. Try to become even more American than you think you are, than you already are.'” The top right panel depicts the two women holding hands and standing in the boat. The text below these panels reads,”‘Just quietly go about your business even though this horribly unconstitutional thing has just happened to you and you’ve suffered all this trauma. But try to be American. Try to fit in.'” The bottom left panel depicts a close-up of the women holding hands above the boat and a ripple in the water. Beneath the hands, the text reads, “We were told, ‘Don’t rock the boat, do not make waves.” Beneath the boat, the text reads, “Nonsense. Let’s go make a Big Splash!” The bottom right panel depicts the two women holding hands and jumping into a sea of waves. Text on the bottom left indicates these quotations are from Jean Hibino’s oral history for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

TOPAZ by Emily Ehlen

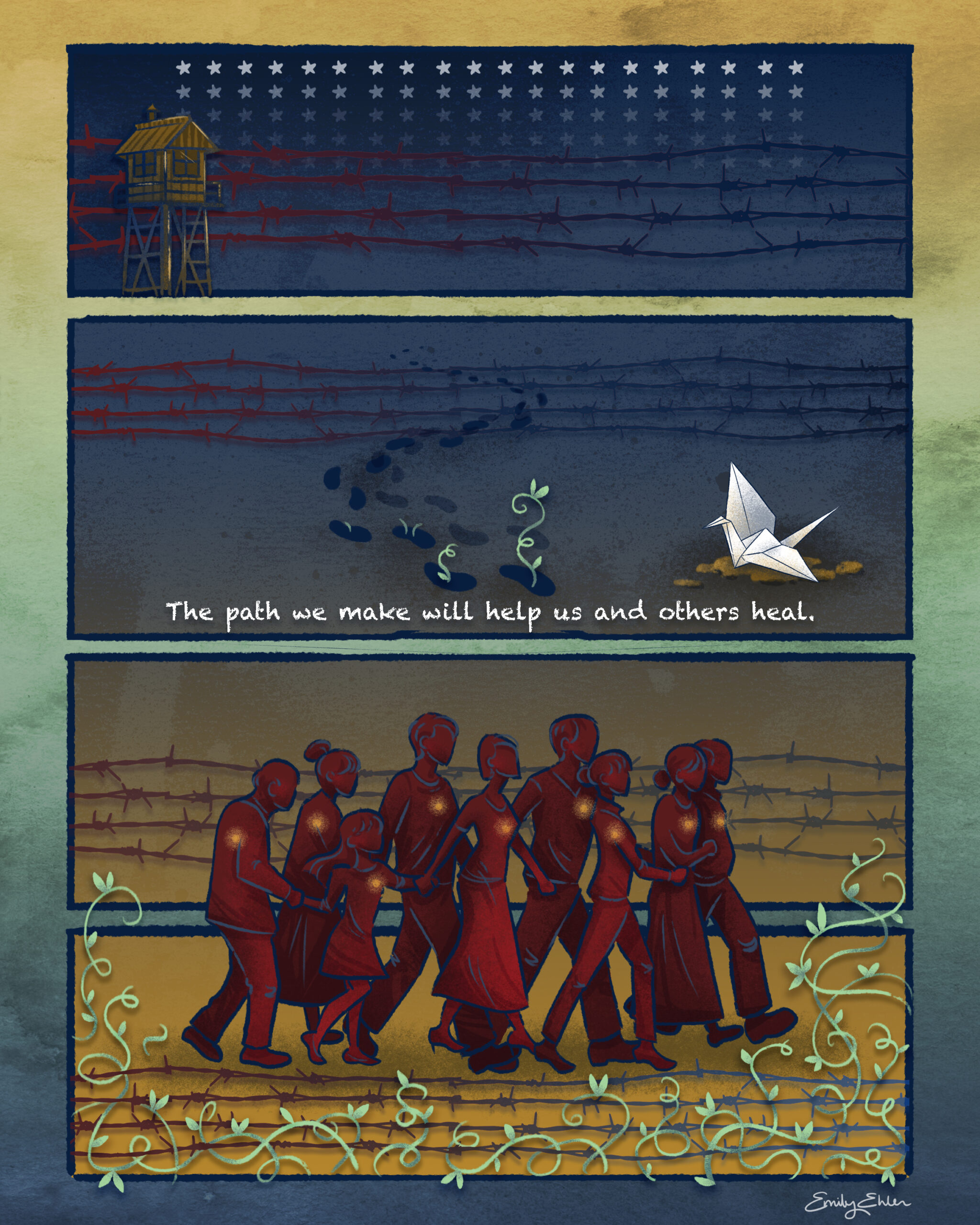

This image titled TOPAZ consists of four panels. The top panel depicts white stars behind barbed wire in red and blue that mimics the American flag, as well as a guard tower. The next panel depicts footsteps with plants sprouting from the final four steps. To the right of the footsteps, a white paper crane rests on soil. Red and blue barbed wire appears in the background. Text at the bottom of this panel reads, “The path we make will help us and others heal.” The bottom two panels depict barbed wire at the top and bottom, which frame a group of people all holding hands walking to the right. The group of people, which includes a range of ages, spans both panels. The individuals have glowing lights over their hearts. Plants sprout from the bottom of this panel.

SILENCES by Emily Ehlen

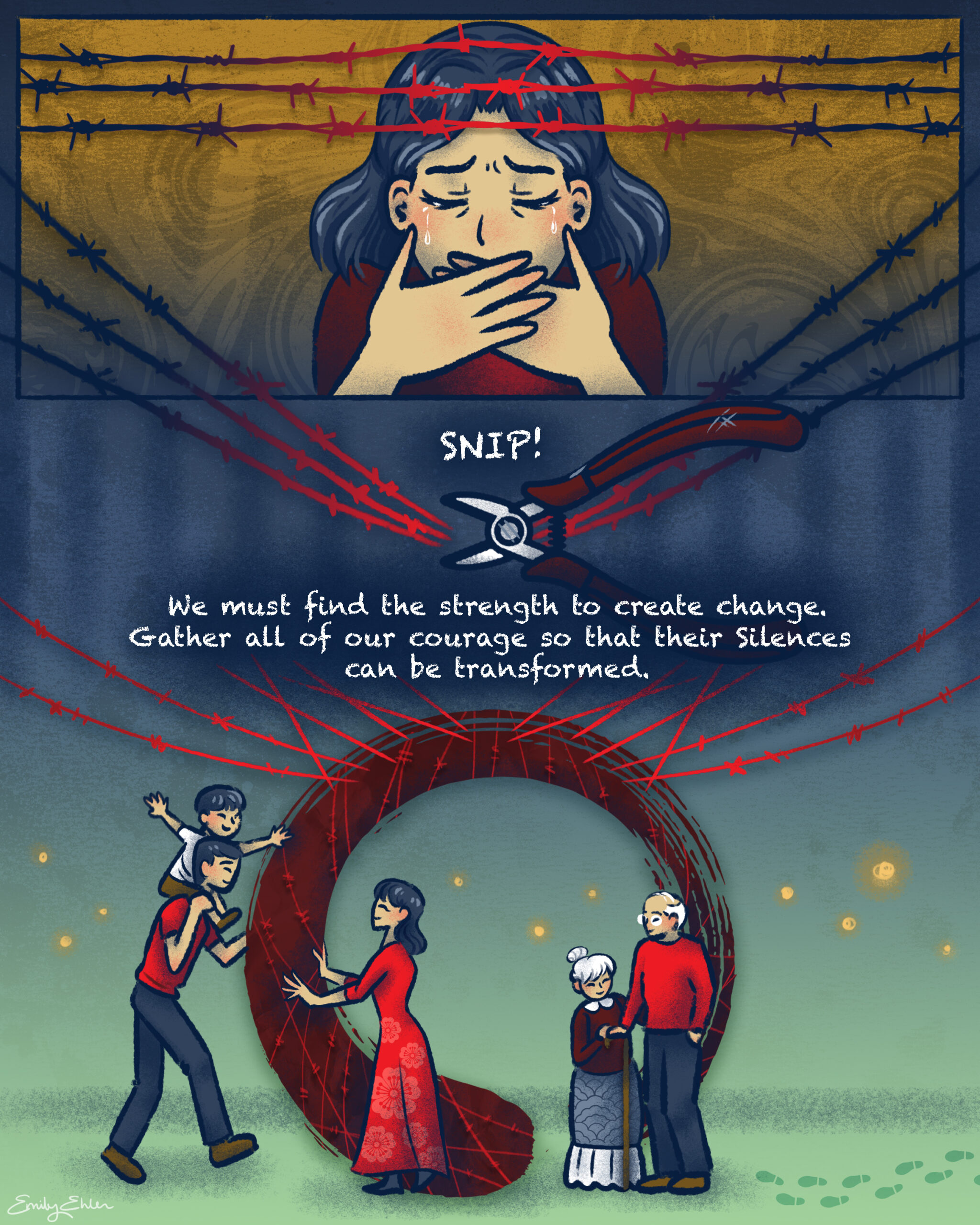

This image titled SILENCES consists of two panels. In the top panel, a woman cries while framed by red barbed wire. The bottom panel depicts wire cutters snipping the red barbed wire. Text reads, “SNIP!” Beneath the barbed wire is text that reads, “We must find the strength to create change. Gather all of our courage so that their silences can be transformed.” Beneath this text is a scene depicting a man with a child on his shoulders moving toward a woman with open arms. To the right of them are an elderly woman and man. Behind the group of people, there is a large, red circular ensō formed from the barbed wire. Glowing lights also appear in the background.

TREE by Emily Ehlen

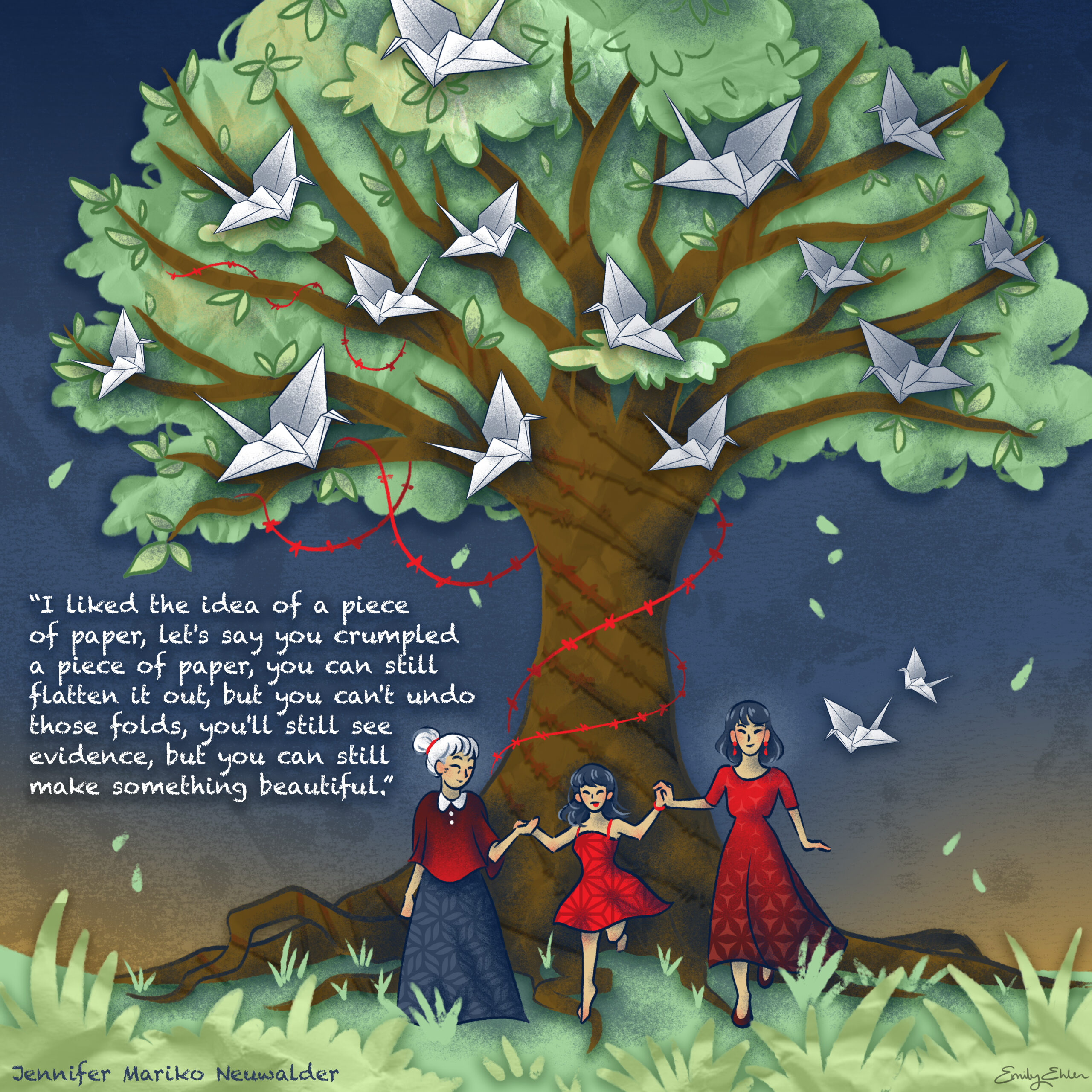

This image titled TREE consists of one panel, depicting three women of different generations holding hands in front of a large tree wrapped in red barbed wire and filled with white paper cranes. This image includes text which reads, “‘I liked the idea of a piece of paper, let’s say you crumpled a piece of paper, you can still flatten it out, but you can’t undo those folds, you’ll still see evidence, but you can still make something beautiful.” Text on the bottom left indicates these quotations are from Jennifer Mariko Neuwalder’s oral history for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

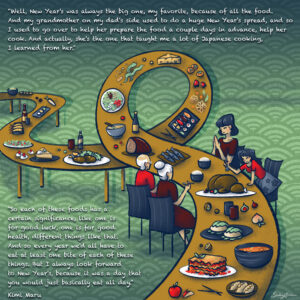

FEAST by Emily Ehlen

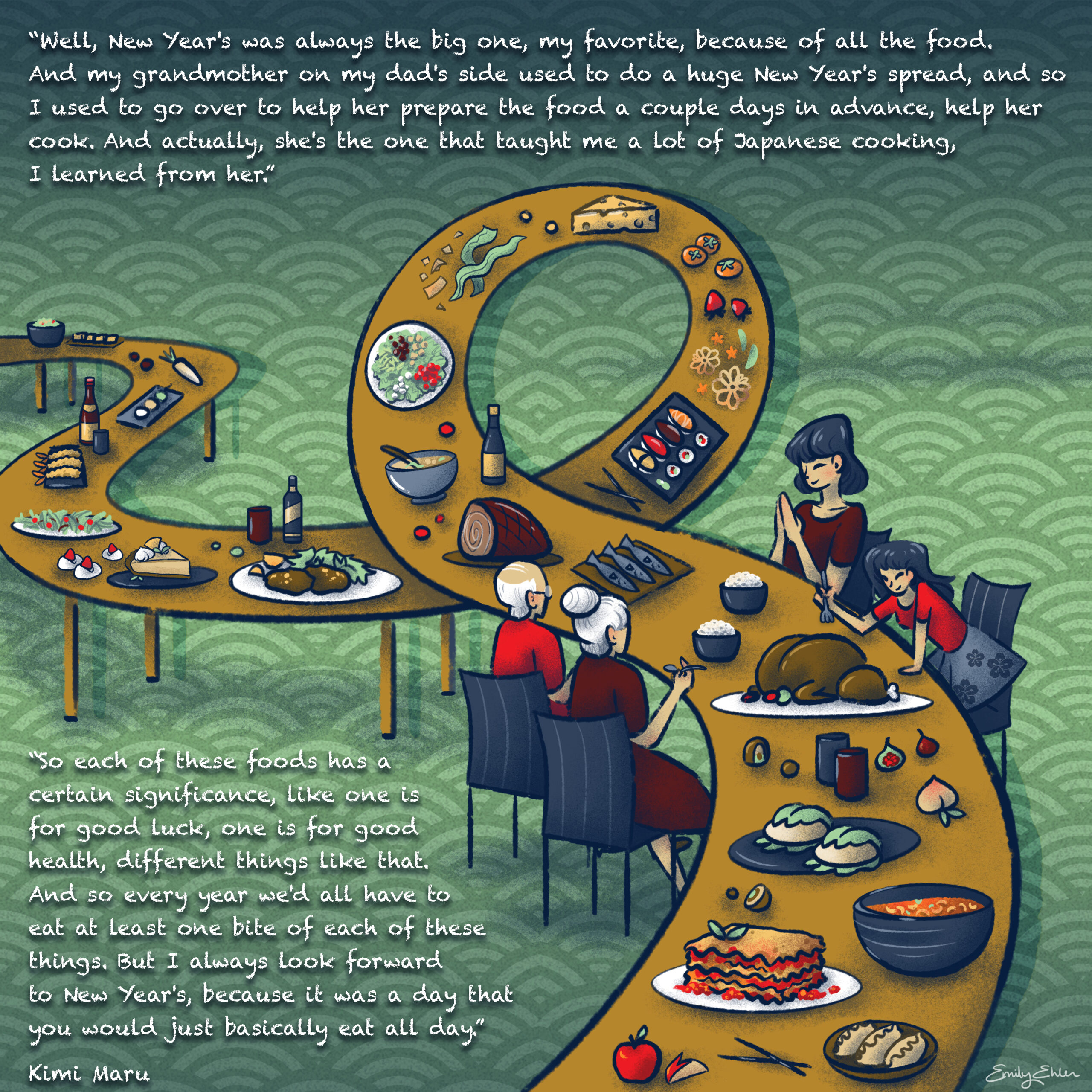

This image titled FEAST consists of one panel that depicts a long table that stretches from the left side to the bottom right which loops before reaching four people of different generations eating. The food on the table includes a variety of foods like sushi, lasagna, salad, turkey, and dumplings. Text at the top of the image reads, “‘Well, New Year’s was always the big one, my favorite, because of all the food. And my grandmother on my dad’s side used to do a huge New Year’s spread, and so I used to go over to help her prepare the food a couple days in advance, help her cook. And actually, she’s the one that taught me a lot of Japanese cooking, I learned from her.'” Text on the bottom left of the image reads,, “‘So each of these foods has a certain significance, like one is for good luck, one is for good health, different things like that. And so every year we’d all have to eat at least one bite of each of these things. But I always look forward to New Year’s, because it was a day that you would just basically eat all day.'” Text on the bottom left indicates these quotations are from Kimi Maru’s oral history for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

Explore the oral history interviews in the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, listen to The Berkeley Remix podcast season “’From Generation to Generation’: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration,” and discover related resources on the Oral History Center website.

Acknowledgments for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project

This project was funded, in part, by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government.

This material received federal financial assistance for the preservation and interpretation of U.S. confinement sites where Japanese Americans were detained during World War II. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability or age in its federally funded assisted projects. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to:

Office of Equal Opportunity

National Park Service

1201 Eye Street, NW (2740)

Washington, DC 20005

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. The Oral History Center is a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. As such, we must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

Q&A with Artist Emily Ehlen on Illustrating the OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project

For the first time, the Oral History Center, or OHC, partnered with an artist named Emily Ehlen, who created ten graphic narrative illustrations based upon stories and themes recorded in the OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, or JAIN project. The JAIN project documents and disseminates the ways in which intergenerational trauma and healing occurred after the United States government’s mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.

The OHC’s JAIN project documents and disseminates the ways in which intergenerational trauma and healing occurred after the United States government’s mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. The OHC team interviewed twenty-three Japanese American survivors and descendants of the World War II incarceration to investigate the impacts of healing and trauma, how this informs collective memory, and how these narratives change across generations. Initial interviews in the JAIN project focused on the Manzanar and Topaz prison camps in California and Utah, respectively. The JAIN project began at the OHC in 2021 with funding from the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant. The grant provided for 100 hours of new oral history interviews, as well as funding for a new season of The Berkeley Remix podcast and Emily Ehlen’s unique artwork, all based on the JAIN project oral histories.

Below is an interview with Emily Ehlen about her processes in creating such dynamic illustrations drawn from the memories and reflections of JAIN oral history narrators. You can see and save copies of larger images of Emily’s artwork for the JAIN project in a separate blog post.

Artist Bio:

Emily Ehlen is best known for her colorful and whimsical illustrations using mixed media. Watercolor, ink, spray paint, and gouache are the primary mediums she uses for her traditional works, and she also integrates them in her digital pieces. She loves being positive and expressing her interests while using her surroundings as inspiration. To invoke curiosity and imagination, her drawings reflect an open view of the subject and are framed with pieces of expression and reality. Change and adaptability are a constant as she goes through various experimentations and approaches to her art.

Q&A with artist Emily Ehlen:

Q: What was your process for creating the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives artwork?

Emily Ehlen: My process started with selecting powerful imagery and phrases in relation to connecting themes found throughout the oral history transcripts. I composed thumbnails with the intent to represent the information clearly and use symbolism to convey the narrative. I wanted to use as much text from the source as I could, but I wanted to avoid it being too word heavy. It was a balancing act of editing the text and imagery to support each other in the composition and narrative. After developing and consolidating the initial drafts I moved on to tighter linework and color concepts. Once the colors were established, I inlaid patterns and handmade textures to add contrast between objects, panels, and the background. The handmade textures were made with ink washes and spray paint. The final step was applying shading and details to enhance the focus of each element while also keeping the flow throughout the entire composition.

Q: How was your work on this project similar or different to your prior art projects?

Emily Ehlen: This Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives art project was similar to the comic series Drawn to Art: Tales of Inspiring Women Artists that I worked on in 2021 for the Smithsonian American Art Museum. For that Smithsonian project, I drew a three page comic called “Weaver’s Weaver,” featuring Kay Sekimachi, a Japanese American artist. My process for both projects were pretty identical. Although, I think I had a little more freedom with expanding the storytelling elements working on the JAIN project comics. Overall, they were mutually great experiences that I am so grateful to have been a part of.

Q: How did engaging with the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives oral history transcripts shape the stories you chose to tell and some of the imagery you used in your graphic art?

Emily Ehlen: When drafting the concepts of the illustrations, I wanted to use imagery that would convey the message the stories presented. Reading the oral history transcripts, I found lots of interesting details to include, like with the different types of food to include in the FEAST composition. It was inspiring to hear everyone’s unique voice sharing aspects about their and their family’s lives.

Q: How did you choose the various scenes and stories that you eventually depicted? What stories in the transcripts most stood out to you? Why?

Emily Ehlen: I illustrate with the goal to portray a story the audience can connect and respond to. I wanted to choose stories with lots of emotions that I could highlight in each drawing. The piece I got the most emotional while drawing was Nancy Ukai’s grandfather in EUCALYPTUS. I sympathized with the longing and sadness of missing Berkeley that her grandfather felt. I understood the rationality behind using the box for something else, but that emphasized just how important Berkeley was to him. It was heartbreaking to read, so I knew I had to draw it.

Q: What are some of the story themes that you worked to express throughout your art for this project?

Emily Ehlen: The focus was how the Japanese American incarceration during World War II impacted themselves, their families, and how they responded to it. The themes were identity and belonging, intergenerational connections, and healing. I wanted the weight of the words to be carried through to the art accompanied with them.

Q: Can you describe some of the visual themes or repeated imagery that you incorporated throughout the various pieces you created? How and why did you develop these visual themes?

Emily Ehlen: The color palette I used helped create the tone and atmosphere of each piece separately while also keeping the collection cohesive. The red was used with duality: the bright saturated hue represented youth, rebelliousness, and intensity; while the dark maroon represented authority and repressed quietness. The soft green color was used to depict change and positivity that connects to the healing theme. The navy blue signifies unity and freedom, but it is used with a sense of serenity and heaviness. For example, the blue in TEACHER extrudes an overbearing presence in contrast to when it’s used in TREE. The ochre yellow has different meanings for its surroundings, like in TEACHER it signifies uncertainty, and in STORIES it’s used to display hope.

The water pattern, waves, and watercolor texture are used with family elements, and it contrasts the dry gritty spray paint texture that references the environment of Topaz and Manzanar. Waves are symbols of growth, renewal, and transformation. They also represent the unpredictability of life, to which people learn to navigate its ups and downs. The plants and paper cranes also relate to family connections, development, and healing, going through many stages and flourishing together.

For darker imagery, I wanted the red barbed wire to be synonymous with the red stripes we see on the American flag. To show the lack of freedom and injustice that the Japanese Americans faced, those stripes became wire that entrapped and left scars on following generations. The guard towers were a beacon of looming authority and danger at the incarceration camps. They became a mental block for some that were confined in their silences.

Q: While creating the JAIN art, what did you learn that was new to you?

Emily Ehlen: I really enjoyed learning about everyone’s perspectives and experiences with being Japanese American. I am Chinese American, so I empathize with the stories about identity and the sense of belonging. This project lit up my desire to discover more about my culture. My motivation for drawing is to see how my art mirrors my development as a person. I think art is a record of growth and change. Like time, it never stops moving forward.

Q: Can you describe one or two of your favorite pieces that you created for this project? Why does this one stand out for you?

Emily Ehlen: This is like asking the question, “Who’s your favorite child?” It’s super difficult because I love each piece for different reasons. I had the most fun drawing the piece SPLASH, about Jean Hibino and her mother. I think it has the most dynamic composition with how the imagery flows together with the text. I like the sequence of stillness to movement, and how a ripple can start a wave.

Q: What are your hopes for how people engage with your art for this project? Who do you hope sees it? What do you hope people take away from your art for this project?

Emily Ehlen: My hope for how people engage with the comic is to have open conversations about them or topics related to it. It would be nice to see what sticks out to people the most and what connections they make through their perspectives. I hope people are able to feel the sentiments in each piece and learn new aspects of its history. I can’t think of anyone specific I’d want to see it, but I strive to be someone who inspires others by taking creative approaches to new ideas. So, I hope other artists who are interested in drawing and story-telling see it

You can see and save copies of larger images of the graphic art that Emily Ehlen created for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project in a separate blog post. We encourage you to use and share Emily Ehlen’s artwork, along with the JAIN project oral history interviews, especially in classrooms when teaching the history and legacy of the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. When using these images, please credit Emily Ehlen as the artist (for example, Fig. 1, Ehlen, Emily, WAVE, digital art, 2023, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley), and see the OHC website for more on permissions when using our oral histories.

Acknowledgments for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project

This project was funded, in part, by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government.

This material received federal financial assistance for the preservation and interpretation of U.S. confinement sites where Japanese Americans were detained during World War II. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability or age in its federally funded assisted projects. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to:

Office of Equal Opportunity

National Park Service

1201 Eye Street, NW (2740)

Washington, DC 20005

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. The Oral History Center is a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. As such, we must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

“Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism,” an Oral History Center exhibit in The Bancroft Library Gallery

We’re excited to announce the opening of Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism, a Bancroft Library Gallery exhibition that was curated by Todd Holmes, Roger Eardley-Pryor, and Paul Burnett of the Oral History Center. Voices for the Environment traces the evolution of environmentalism in the San Francisco Bay Area across the twentieth century. In three sections, it highlights how Bay Area activists have long been on the front lines of environmental change—from efforts to preserve natural spaces in the wake of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, to the midcentury fight for state regulations to protect San Francisco Bay shoreline, to more recent demands for environmental justice to address the disproportionate burden of pollution that sickened communities of color around the Bay.

Our Voices for the Environment exhibit is the first major effort in The Bancroft Library Gallery to showcase oral history alongside the traditional archival collections of The Bancroft Library, with the oral history collections leading the way. The exhibit still features historic photographs, pamphlets, post cards, and posters selected from several collections of The Bancroft’s physical archives. But for the first time in this gallery, our Voices for the Environment exhibit also includes three installations of special Audio Spotlight technology where you can listen to never-before-heard oral history recordings with Bay Area environmentalists, while simultaneously watching three videos edited by Todd Holmes that feature historic photographs and rare film footage from The Bancroft’s digital collections. Additionally, as a complement to the exhibit, curators Todd Holmes and Roger Eardley-Pryor created an educational workbook, so students of all ages can learn about the environmental movement by engaging with the themes and primary sources on display. Through these efforts, the Oral History Center hopes Voices for the Environment will have a life beyond its yearlong run.

For an even deeper dive, you can also scan a QR code in the gallery, or click the following link, to hear three Voices for the Environment podcast episodes produced in partnership with Sasha Khokha of KQED Public Radio and The California Report Magazine. The podcast episode for section 1 of the exhibit, titled “A Preservationist Spirit,” traces the environmental activism that arose amid the rebuilding efforts of San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake and fire, efforts that came to target the state’s ancient redwood forests and the beloved Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park. The episode features historic interviews from the Oral History Center archives including segments from the “Growing Up in the Cities” collection recorded in the late 1970s by Frederick M. Wirt, as well as oral history interviews with Carolyn Merchant recorded in 2022, with Ansel Adams recorded in the mid-1970s, and with David Brower recorded in the mid-1970s. The oral history of William E. Colby from 1953 was voiced by Anders Hauge, and the oral history of Francis Farquhar from 1958 was voiced by Ross Bradford. This first episode also features audio from the film Two Yosemites, directed and narrated by David Brower in 1955. The podcast episode for section 2 of the exhibit, titled “Tides of Conservation,” tells the story of the Save San Francisco Bay movement and the creation of the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC), one the nation’s first environmental regulatory agencies. The episode features segments from oral history interviews with Save The Bay founders Esther Gulick, Catherine “Kay” Kerr, and Sylvia McLaughlin recorded in 1985; as well as interviews with BCDC executive director Joseph Bodovitz and chairman Melvin B. Lane, both recorded in 1984. And the podcast episode for section 3 of the exhibit, titled “Environmental Justice for All,” spotlights efforts by communities of color to place the health of people within the environmental agenda, including creation of new environmental organizations like the West County Toxics Coalition, the Urban Habitat Program, and APEN (Asian Pacific Environmental Network), all founded in the Bay Area. The episode features segments from oral history interviews with Carl Anthony, Pamela Tau Lee, Henry Clark, and Ahmadia Thomas, all recorded in 1999 and 2000.

The Voices for the Environment exhibition space was designed by Gordon Chun and is free and open to the public Monday through Friday between 10am to 4pm from Oct. 6, 2023 to Nov. 15, 2024, in The Bancroft Library Gallery, located just inside the east entrance of The Bancroft Library.

We hope you come to campus and experience it!

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. While we receive modest institutional support, we are a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. We must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

“Robert Cox: Sierra Club President 1994-96, 2000-01, and 2007-08, on Environmental Communications and Strategy,” oral history release

New oral history: “Robert Cox: Sierra Club President 1994-96, 2000-01, and 2007-08, on Environmental Communications and Strategy”

Video clip from Robert Cox’s oral history on the Sierra Club’s environmental justice work with Jesus People Against Pollution (JPAP) in 1994

Robert Cox is a scholar and a gentleman. He also has a fire burning in his belly for protecting nature, confronting injustice, and empowering people, which fueled his long-time leadership in environmental politics, strategy, and influential communication. Robbie Cox served three times as president of the national Sierra Club in 1994-96, 2000-01, and 2007-08. He is Professor Emeritus at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH), and as a scholar of activist rhetoric, Cox helped found the academic field of environmental communication.

Robbie and I recorded nearly eleven hours of his life history over Zoom during five interview sessions in September 2020, during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Robbie’s inspiring stories of environmental activism produced a 253-page transcript, which includes an appendix with several photographs. The stories that Robbie shared in his oral history also emphasized the incredibly high stakes for our present moment of environmental politics, rhetoric, and civic engagement.

Cox was born in September 1945, in Hinton, West Virginia, where his early influences included roaming Appalachian forests and rivers as well as his family’s history of union organizing and work toward social justice. He was recruited to the debate team at the University of Richmond where, from 1963 to 1967, he studied communication, philosophy, history, and religion while also participating in civil rights protests. In 1970, Cox earned his Ph.D. in classical rhetoric studies from the University of Pittsburgh with a dissertation on the rhetorical structures of the Vietnam antiwar movement in which he actively participated. From 1971 to 2010, Cox was a Professor in the Department of Communication at UNC-CH where he helped establish the field of environmental communication and focused his research and teaching on argumentation, rhetorical theory, and social movements. Cox married Professor Julia Wood in 1975 when she also joined the UNC-CH faculty in the Department of Communication.

Video clip from Robert Cox’s oral history on first joining the Sierra Club in 1979

Upon Dr. Wood’s suggestion, Cox joined the Sierra Club in 1979 and, over time, he earned leadership positions at every level in the Club: as chair of the Research Triangle Group, as chair of the North Carolina Chapter, and as an elected member to the national board of directors for most years between 1993 and 2013, including three times as president of the national Sierra Club. Cox made significant contributions to passage in the US Congress of the North Carolina Wilderness Bill, to the Sierra Club’s early engagements in the environmental justice movement, to restructuring both the Club’s internal governance and its volunteer structure, as well as helping lead Sierra Club engagements in national politics, particularly during his times as Club president. In this oral history, Cox discusses all of the above, with a focus on leveraging influential communication and strategy, while also sharing his experiences hiking and trekking in the Himalayas, in the mountains of Europe, and in the Appalachian Mountains.

Robbie Cox’s oral history is significant for detailing the environmental activism and political strategies of one of the most influential volunteers in recent Sierra Club history. Some of the themes throughout Robbie’s oral history include the profoundly democratic nature of the Sierra Club, details on the Club’s geographically diverse grassroots activism, as well as numerous ways that volunteer environmentalists work together to shape state and national legislation. Robbie also reconstructed the ways he balanced his double life as UNC professor with his life as an environmental activist, especially through his work in Sierra Club media campaigns. He recounted his decades as a nationally elected volunteer leader in the Sierra Club, as told through the perspective of an academic scholar of rhetoric and communications. And throughout, Robbie shared stories of direct action for environmental causes at all levels of Sierra Club engagement, from local to national.

Video clip from Robert Cox’s oral history on passing the North Carolina Wilderness Act in 1984

The in-depth, life-history approach used in this oral history reveals ways that Robbie’s personal influences and his engagements in the Sierra Club evolved over time. For instance, Robbie’s family history of labor activism instilled in him the power of people and the importance of social justice. Similarly, his participation on debate teams shaped substantially his education and academic work, while also playing a central role throughout his life as a political and environmental activist. Robbie’s interview also explored the Sierra Club’s and his own personal engagements with environmental justice, including his attendance at the First National People of Color Environmental Justice Leadership Summit in 1991, his leveraging of media in the national Sierra Club’s partnership with “Jesus People Against Pollution” in Mississippi, as well as his experiences on toxic tours of colonias in Matamoro, Mexico, along with other actions against the negative results of neoliberal free trade agreements.

Robbie also shared insider details on several significant moments in the Sierra Club’s recent history. He recounted the Club’s severe financial crises in the 1990s that resulted in his work to reorganize the Club’s internal governance through Project Renewal as well as the Club’s volunteer structures via Project ACT. Robbie recounted his central role in the Sierra Club’s efforts to combat the de-regulatory and anti-environmental Congressional agenda in wake of Newt Gingrich’s Republican take-over of Congress in the 1990s, as well as Robbie’s personal role in securing the Sierra Club’s endorsement of Al Gore, for whom Robbie campaigned in 2000. Robbie also detailed the central role he played in the Groundswell Sierra campaign in the early 2000s to resist a take-over of the Sierra Club by anti-immigration and white supremacist forces. And as the world warms and the seas rise, Robbie discussed ways that the Sierra Club has confronted the compounding crises of climate change in the twenty-first century. Robbie’s decades of environmental activism provides a lens on ways the environmental movement has evolved over time from its early focus on wild lands, to concerns about human health, to engagement on issues of environmental justice, to the modern complexities of climate change. Robbie also reflects on the contemporary Sierra Club’s internal and external challenges in its ongoing work for equity, inclusion, and justice.

Video clip from Robert Cox’s oral history on delivering to Congress the Environmental Bill of Rights with 1.2 million signatures in 1995

Back in the summer of 2020, when I spoke with Carl Pope, former Sierra Club executive director, to prepare for Robbie’s oral history, Pope recalled Robbie’s exceptional leadership and effectiveness. When “Professor Cox” first won election to the national Sierra Club board of directors in the 1990s, Pope described Robbie’s presence as “immediately noticeable.” Pope told me how Robbie used his expertise in rhetoric to unify people and advance proposals for environmental action. “You could see Robbie work at a board meeting,” Pope remembered. “When he wanted to get the board to agree, he would offer some initial proposal tentatively, then let folks respond to it and let the room talk. Then he’d come back in and make the same proposal, but he changed two words to see if that worked. He’d keep playing with the proposal and make changes rhetorically, until he got something that would work for everyone.” The Sierra Club’s board of directors come increasingly from a variety of backgrounds across the United States. All directors are volunteers, not employed staff, but like much of the Sierra Club staff, many Club directors consider themselves to be full-time environmental activists. As Carl Pope noted, however, most Sierra Club directors “are not professional communicators. People would talk past each other. Robbie’s skill on the board lubricated that process, which was phenomenally helpful. If anyone wanted to get something done, you asked Robbie.” Indeed, Robbie Cox got things done.

Pope also described Robbie as a kind of environmental philosopher. “He wasn’t ideological,” Pope explained, “but surely, he had his own vision of where the Club should go.” Now, with this publication of Robbie Cox’s oral history, you too can have him tell you in his own words about his visions for the Sierra Club and the ways he mobilized constituencies to make a reality of his visions for environmental protection, political power, and justice.

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. While we receive modest institutional support, we are a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. We must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

Podcast episode 3: “Environmental Justice for All” in The Bancroft Gallery exhibit VOICES FOR THE ENVIRONMENT: A CENTURY OF BAY AREA ACTIVISM

Listen to podcast episode 3, “Environmental Justice for All,” or read a written version of this podcast episode below.

Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism is a gallery exhibition in The Bancroft Library that charts the evolution of environmentalism in the San Francisco Bay Area through the voices of activists who advanced their causes throughout the twentieth century—from wilderness preservation, to economic regulation, to environmental justice. The exhibition is free and open to the public Monday through Friday between 10am to 4pm from Oct. 6, 2023 to Nov. 15, 2024, in The Bancroft Library Gallery, located just inside the east entrance of The Bancroft Library. Curated by UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center, this interactive exhibit is the first in-depth effort to showcase oral history along with other archival collections of The Bancroft Library.

This exhibition includes three podcast episodes that offer deeper narratives to supplement the archival posters, pamphlets, postcards, photographs, oral history recordings, and film footage that are also presented in the gallery. Please use headphones when listening to podcasts in The Bancroft Library Gallery.

A written version of podcast episode 3 is included below.

Listen to episode 3: “Environmental Justice for All” on SoundCloud.

PODCAST EPISODE SHOW NOTES:

Episode 3: “Environmental Justice for All.” This podcast episode accompanies a section of the Voices for the Environment exhibition that explores how, in the 1980s and 90s, communities of color in the Bay Area fought against environmental racism by creating new organizations, such as the Urban Habitat Program, to demand environmental justice—the equal treatment and meaningful involvement of all people in environmental decision-making. In the city of Richmond, activists in the West County Toxics Coalition and the Asian Pacific Environmental Network, or APEN, organized against toxic threats from the area’s petrochemical and hazardous waste facilities. Environmental justice activists helped transform the American environmental movement from one focused mostly on landscapes to one that increasingly includes the health and wellbeing of historically disenfranchised people.

This podcast episode features historic interviews from the Oral History Center archives in The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, including segments from oral history interviews with Carl Anthony, Pamela Tau Lee, Henry Clark, and Ahmadia Thomas, all recorded in 1999 and 2000. This episode was narrated by Sasha Khokha, with thanks to KQED Public Radio and The California Report Magazine.

This podcast was produced by Todd Holmes and Roger Eardley-Pryor of the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, with help from Sasha Khokha of KQED. The album and episode images were designed by Gordon Chun.

WRITTEN VERSION OF PODCAST EPISODE 3: “Environmental Justice for All”

Pamela Tau Lee: We cannot be afraid to talk about environmental racism. We cannot be afraid to discuss that, talk about what it means: the discrimination of communities in environmental policy and being left out of the process.

Sasha Khokha: What does justice look like? Whose lives matter? And how does that relate to the environment? In the 1980s and 90s, concerns about toxic industrial waste led communities of color in the Bay Area, and across the nation, to create new organizations and demand environmental justice—the equal treatment and meaningful involvement of all people in environmental decision-making.

Pamela Tau Lee: What we need to deal with is the racism that is the root cause of why industry was targeting communities of color: because communities of color would not have any power; that it’s much more acceptable to dump this stuff in communities of color. So if we shied away from talking about racism, we would then not be able to articulate the realities, and we felt it was racism.

[music]

Sasha Khokha: Welcome to Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism. This podcast accompanies an exhibition in The Bancroft Gallery at UC Berkeley that’s the first major effort to bring together both the oral history and archival collections of The Bancroft Library. The voices you’ll hear were recorded by UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center, founded in 1953 to record and preserve the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world.

Voices for the Environment traces the evolution of environmentalism in the San Francisco Bay Area across the twentieth century, and highlights ways that Bay Area activists have been on the front lines of environmental change.

This is our third and final episode, called “Environmental Justice for All.” I’m your host, Sasha Khokha, from KQED.

[harmonica blues music]

Sasha Khokha: Communities of color have long confronted environmental racism—the disproportionate burden of toxic waste and industrial pollution in neighborhoods that are mostly low income and home to BIPOC folks. But up until the 1980s, the big players in the environmental movement focused on other issues, like preserving redwood groves or protecting bay shoreline from new construction.

Pamela Tau Lee: I think many of the mainstream organizations, you know, they don’t focus on people. They focus on the ecology and other natural resources.

Sasha Khokha: That’s Pamela Tau Lee, a environmental and labor activist from San Francisco whose oral history you’re hearing.

Pamela Tau Lee: These predominantly white organizations did not want to really acknowledge that there was a different experience felt by communities of color.

Sasha Khokha: Take the city of Richmond, where more than 75% of residents identified as people of color in the 2022 census. Located along the bay above Berkeley and Oakland, Richmond has been home to the Chevron oil refinery since 1902. A host of other polluting industries were established there, too. As a result, people in Richmond experience higher levels of pollution and toxins, and have less access to healthy environments to live and play. In the mid-1980s, Richmond residents formed the West County Toxics Coalition. It’s a multi-racial organization aimed at empowering the community to have a greater voice in the environmental issues impacting their neighborhoods.

Henry Clark: You know, like anyone born and raised in North Richmond, we know that there was environmental problems there, you know, over your whole lifetime. So it was quite only logical when the West County Toxics Coalition was formed and they began to organize in North Richmond.

Sasha Khokha: That’s Henry Clark, who grew up in North Richmond. In 1986, after earning his Ph.D. in religious studies, Clark became executive director of the West County Toxics Coalition, and he led it for more than three decades. As a kid in North Richmond, Henry Clark’s home was directly next door to the Chevron oil refinery.

Henry Clark: I can remember clearly waking up many mornings and finding the leaves on the tree burnt crisp overnight from chemical exposure, or you know, going outside and the air would be so foul that you would literally have to grab your nose and try to not breathe the air and go back in the house and wait until it was cleared up. Those type of situations, you know, were a common experience.

Sasha Khokha: Ahmadia Thomas also knows about the foul air in Richmond. She moved there in the mid-1970s and was active in community organizing.

Ahmadia Thomas: Well, then I first came here, I didn’t know, but I used to smell these terrible odors. And I’d say, “What’s that?” And my husband said, “We all smelled it all the time, and we ain’t never made no kick about it.” But they didn’t know what they were smelling. And they were terrible odors: you know ones that smell like sulfur once in a while. Terrible odors out here, after I got out here. When I first came, I didn’t remember smelling all this stuff, but boy, after I was out here a while, I really got environmentally conscious.

Sasha Khokha: Thomas joined the West County Toxics Coalition, too, in part because she was concerned about how Richmond’s industrial pollution was affecting her health—and her neighbors’ health.

Ahmadia Thomas: Like a lot of people had long-term illnesses. Like, these illnesses we don’t know whether they’re short-term or long-term. But if you’ve been affected, say, five years ago and you’re still affected, well now that’s a long term. But, see, a lot of them has been affected. Children, too.

Sasha Khokha: Regular chemical exposures contributed to those illnesses, and so did the periodic accidents, fires, and explosions at the Chevron refinery.

Ahmadia Thomas: And then when they started having the accidents—whoo! There was always a fire or accident. It would be on the TV or in the paper: “There was an accident, but it wasn’t no harm to your health.” And that ain’t true! [laughs] Got to hearing that.

Sasha Khokha: Here’s Henry Clark again.

Henry Clark: You know, these chemical disasters, they do affect people’s lives and people do die from them. You usually don’t hear about the deaths that do occur. You now, they just end up being faceless people whose families may be aware of it, but most of the time you don’t hear about that. Nor do you really even get a good sense of the health impacts, because usually there’s no type of comprehensive health studies that are done or conducted after these disasters.

Sasha Khokha: But the health studies that have been conducted are clear.

Henry Clark: I do know that there’s a 33 percent higher than state average lung cancer rate throughout the Richmond area stretching actually throughout the county, stretching through the industrial corridor.

Sasha Khokha: Here’s Carl Anthony. He’s an architect, a city planner, and a former professor at UC Berkeley.

Carl Anthony: The communities get it. You don’t have to have a Ph.D. to figure out if you have asthma rates five or six times the regional average, it’s clearly symbolic of racism. It is an environmental racism.

Sasha Khokha: With so many other Bay Area groups focused on land, trees, and wildlife, Carl Anthony saw the need for a new organization to deal with the complex urban issues confronting communities of color.

[blues music]

In 1989, Anthony co-founded the Urban Habitat Program to focus on people who lived in cities. He envisioned it would be as multi-racial and multicultural as the Bay Area where he lived. And to better understand the connections between social injustice, economic inequality, and environmental racism, Anthony also helped create a groundbreaking journal, first published on Earth Day in 1990, called Race, Poverty, and the Environment.

Carl Anthony: When we began the Race, Poverty, and the Environment journal, we started looking at these. What is the energy cycle? We began to see that the whole system of extracting energy, distributing it, consuming it, and waste, at every step were huge social issues.

Sasha Khokha: Like the chemical pollution near oil refineries, or the health and safety issues for workers there, or the high cost of energy for low income people: all intertwined social and environmental issues. As executive director of the Urban Habitat Program, Carl Anthony built upon the Bay Area’s progressive and environmental traditions, with a focus on community-led decision making and public investment in historically disenfranchised neighborhoods. But, the more Anthony engaged with issues of environmental justice, the more problems he saw in the ways that mainstream, mostly white American environmental activists understood their own history.

Carl Anthony: There was a deep problem in the myth of the environmental movement, the story of the environmental movement, as having grown out of a certain understanding about the settlement of North America. Put really briefly, the settlement began in New England when the Puritans arrived, and then they found an empty wilderness, and they cleared the forests and built the dams and the towns, and came all the way across the country, and then they looked back and saw how much devastation they had made.

Sasha Khokha: By the start of the 20th century, that environmental devastation inspired the early conservation movement, led by preservationists like John Muir. But for Carl Anthony, this narrative focused too much on wilderness and the conservation of public lands, and not enough on the history of race and American expansion.

Carl Anthony: You know, if you look back a little bit, you say, “Wait a minute, hold it, what’s wrong with this model?” First of all, the North American continent wasn’t empty. There were ten million people here. So where do they fit in this story? And then, millions of people were brought from Africa who worked the land—now it has been eighteen generations—where do they fit in this story? And in particular, from the point of view of the racial issues, the things that were missing in the John Muir model was that this was the end of manifest destiny. It was the end of the frontier wars with the Indians. These were the years when there was rampant racism against Chinese people and against Japanese people in California; the years when Jim Crow was established, and the national parks were set up that were white only.

Sasha Khokha: If the old land-focused narrative of American environmentalism ignored social and racial issues, it also overlooked the urban issues that Carl Anthony was so passionate about.

Carl Anthony: So, the point I’m making about cities is that the environmental movement took off in many ways by saying, “We’re not connected with that whole thing, that mess around the cities. We’re not going to deal with that.” So there was this big hole. But in many ways, the issues that people are complaining about—whether it’s global warming, or whether it’s the squandering of, you know, chopping down the trees, whatever it is—are rooted in the way that we’re living in cities. So I felt that by setting up the Urban Habitat Program, we would then be in the position to be able to say, “This is how we need to think and act in relationship to restoring our cities. Here’s how we’re going to address the environmental issues; here’s how we’re going to address the social justice issues; here’s how we are going to address the economic issues. And because you care so much about biodiversity and energy efficiency and all these things, we would like to invite you to participate with us in doing that.”

[music]

Sasha Khokha: Bay Area activists soon discovered they weren’t alone in the fight for environmental justice. Shortly after starting the Urban Habitat Program, Anthony learned about the Toxic Wastes and Race report published in New York by the United Church of Christ’s Commission on Racial Justice. That analysis showed how government agencies across the nation consistently located toxic waste facilities in communities of color. And when the Church and other groups began to organize a national summit on environmental justice, the Bay Area sent a huge contingent.

Pamela Tau Lee: . . . 1991, in Washington DC, was so powerful to see people of color in this room talking about their struggles for justice in this country. I had not heard anything as dynamic and comprehensive since the Civil Rights [Movement] when I was young.

Sasha Khokha: Pamela Tau Lee, then a labor activist in San Francisco, attended that First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit.

Pamela Tau Lee: When you came into that room, you saw native people from Alaska, the deserts of Nevada, the Shoshone tribe. You saw African Americans who lived in small towns in the middle of Alabama, from the South, New Orleans, with African Americans from Harlem, and Detroit, and South Central Los Angeles. You saw brown people from Puerto Rico, from the border, together with Chicanos from New Mexico and California and farmworkers.

Sasha Khokha: At the summit, leaders of color shared examples of environmental racism from across the country, and they discussed what to do about it.

Pamela Tau Lee: People were there to articulate, what is it that we are experiencing? And what is it that we want? And what it is that we stand for? One is we cannot be afraid to talk about environmental racism. In many of the discussions when we start to talk with the traditional environmentalists, who are mainly white, or the government, they were very afraid of that term. And we said we cannot be afraid to discuss that, talk about what it means: the discrimination of communities in environmental policy and being left out of the process. The mainstream environmentalists, they didn’t want us to say anything about racism. They wanted us to use the word “equity.” And what we need to deal with is the racism that is the root cause of why industry was targeting communities of color: because communities of color would not have any power, that it’s much more acceptable to dump this stuff in communities of color. So if we shied away from talking about racism, we would then not be able to articulate the realities, and we felt it was racism.

Sasha Khokha: As Pamela Tau Lee recalled, activists at the summit also discussed a way forward: demanding justice and taking action.