Tag: oral history center

My First Brush with Oral History

I first encountered oral history in my master’s program in history at California State University, Fullerton. I chose the program because it had strong public history training, but in my research about the school I discovered the pedagogy included something called “oral history.” I scratched my head at that, but added that information to a laundry list of graduate school problems labeled: “I guess I’ll figure it out when I get there.” After all, I wanted training to be a museum curator – and nothing else.

Things didn’t go according to plan.

My introduction to oral history was immediate. In my first public history course, a fateful assignment meant I needed to lead a small group discussion about oral history as historical evidence and as practice. My sense of oral history at the time was pretty limited to oral tradition: elders informally sharing knowledge about the past. My group consisted of undergraduates and graduate students who also had little to no experience with oral history, so we set out to discuss: what is oral history and what is its value to public historians?

We debated the reliability of oral history, given its dependence on memory and subjective experiences. We talked about how differing approaches to transcription shade researchers’ experience with oral history source material. We also questioned whether oral history had a place in public history writ large, or if it should be a separate discipline. And yet, we all agreed that it was important to record people’s life experiences, that their stories are inherently valuable.

I began the assignment deeply skeptical of oral history, but at some point during this discussion I found myself defending the practice because of the value of these alternate stories. In part, public history springs from an activist tradition hoping to recover pasts not about white male leaders, but of the everyday and everyman. With that framework in mind, I ended up posing the question: is oral history the most egalitarian practice in public history?

My argument was that much of the time museum exhibits are the result of so-called experts communicating history to the public; it’s an expensive and laborious process that doesn’t always involve the people who witnessed the history presented in the exhibit. But oral history, it’s different. At its core, oral history involves two people sitting down to chat using potentially inexpensive equipment to record their conversation. This process takes place outside the Ivory Tower and requires talking – and really listening – to people in your community, people whose lives and expertise have often been under acknowledged or completely overlooked. In theory, oral history can invert the power structure of just who is the expert. Unlike the rest of the historical profession, oral historians don’t just study the past, they help shape documents about the past by interacting with the people who lived it.

It was during this initial assignment about oral history that I began to question where oral history fits with other historical evidence. I eventually concluded that oral history is different from other text-based sources because it comes with a set of complications about collecting the information. And yet, oral history is also different because sharing human experiences through oral tradition is a powerful tool in making sweeping historical narratives personal and relatable – this connection to the past is difficult to achieve through census records.

It was through these discussions and further exposure to the value of first-person interviews that I finally resolved my questions about how oral history relates to public history. And oral history has become an important mainstay in my toolkit in my career as a public historian.

William C. Gordon: A Life in Libraries, the Law, and Literary Noir

Image by Ana Portnoy, 2017

We are excited to announce the release of our oral history interview will William C. Gordon, lawyer, noir writer, and library supporter. He was born and raised in Los Angeles, California and attended college at the University of California, Berkeley. He earned his law degree at the University of California, Hastings College of Law. He worked as a lawyer in San Francisco for many years before becoming a mystery writer. He is the author of six books, including The Chinese Jars, King of the Bottom, and The Halls of Power, among others. He is also an enthusiastic supporter of libraries, and has made significant contributions to the Whittier High Library and to The Bancroft Library for their burgeoning California Detective Fiction Collection.

OHC Interviewer Shanna Farrell sat down with Gordon in 2017 to discuss his early life growing up in Los Angeles, his affinity for libraries, education and career in the Bay Area, and becoming a writer in his retirement.

Paul A. Bissinger, Jr.: Lifelong San Franciscan and Patron of the Arts

We are pleased to announce the release of our interview with Paul A. Bissinger, Jr. Bissinger was born in San Francisco, California in 1934 to Paul Bissinger and Marjorie Pearl Walter-Bissinger. He was raised on Divisidero Street and attended the Town School. He attended high school at the Phillips Exeter Academy, attended college at Stanford University, and earned a graduate degree from the American Institute for Foreign Trade. He served in the Navy in the 1950s, which took him to Japan, Hong Kong, and Manila. He’s been a life-long patron of the arts, which began as a child. He has a passion for the San Francisco Youth Orchestra, which he has been involved with for many years, and his service was honored by a performance dedicated to him on his 70th birthday.

In his interview, Bissinger discusses his early life, education, time in the Navy, meeting his wife, Kathy, and starting a family, working for his family business, and commitment to the local arts community. He also talks about serving on multiple boards for arts organizations, including for the San Francisco Youth Orchestra and Asian Art Museum.

OHC Announces Summer Fellowship for UC Graduate Student of Color

UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center is offering a $2,000 summer fellowship to a graduate student of color enrolled in the UC system. Aimed at early to mid-career oral historians, this fellowship provides an opportunity to conduct a longform life history interview with a leading figure in the arts or humanities. The selected fellow will conduct a 4-8 hour interview on video, which will be archived at The Bancroft Library. The fellow will see the interview series through from conception to completion and will present on their project at the Oral History Center’s annual Summer Institute.

This fellowship is open to graduate students of color who are enrolled in the UC system. Preference will be given to projects with a U.S. focus, but consideration will be given to international projects that have impact in the U.S.

The fellow will work with OHC Interviewer Shanna Farrell to hone project planning, the structure of the interview, and presentation. Interviewing will take place during June, July, and August. The fellow is expected to be on UC Berkeley’s campus during the Summer Institute, which takes place from August 5-9, 2019. The fellow will have the opportunity to work out of the Doe Library and check books out as needed. Equipment (if needed) and transcription for the interviews will be provided by the Oral History Center.

Applications are open January 14 – February 25, 2019. Award notifications will be send out in late March. Please email Shanna Farrell at sfarrell@library.berkeley.edu with any questions.

OHC Director’s Column – January 2019

From the Oral History Center Director:

Paul “Pete” Bancroft, III, a 1951 graduate of Yale, a pioneer in venture capital, and the eldest great-grandson of Bancroft Library founder Hubert Howe Bancroft, died peacefully in his sleep on January 3, 2019, at the age of 88.

We at The Bancroft Library’s Oral History Center are extremely grateful for his support of over the years. The word “support,” however, is wholly inadequate to capture what he did for oral history at Berkeley. Pete Bancroft was, in fact, its greatest single benefactor in the 65-year history of our office.

Pete’s first major engagement with the Oral History Center (or, as we were known at the time, the Regional Oral History Office) began around 2007 with discussions about a possible oral history project documenting the history of venture capital in the Bay Area. Not only did Pete step forward to sponsor the project, he played a critical role in helping to articulate the major themes and issues to be covered in the interviews. He also created an advisory committee of scholars and leaders in the field that gave the project instant credibility and served on that committee; and he reached out personally to many of the key players whom we wished to interview, setting forth the goals of the project and convincing those who might have been reluctant to participate. Sally Hughes, who was the project director and interviewer for these oral histories, wrote to me upon learning of Pete’s death: “As the interviewer for the Center’s venture capital project, I could not have asked for a better sponsor in organizing, completely funding, and advising the project every step of the way. In his warm and supportive manner, he made it clear that we were a partnership in trying to create the best possible series of interviews on the foundational era of venture capital. It was a subject dear to his heart as one of its early participants.” When completed, the project resulted in 19 lengthy oral history interviews with the pioneers of venture capital, including Franklin “Pitch” Johnson, Art Rock, Reid Dennis, Tom Perkins, Don Lucas, Don Valentine, Bill Draper, Bill Bowes, and Pete himself. In addition, Pete facilitated the donation of another group of interviews already conducted by the National Venture Capital Association. Pete Bancroft played a crucial role in creating this “must read” resource for anyone interested in the history of venture capital.

The years around the financial crisis of 2008 were difficult ones for this office. In addition to waning donations and external support, several retirements left us greatly understaffed. For the few of us remaining, myself included, there was a nervously voiced worry that the fifty-plus year tradition of oral history at Berkeley might be reaching an end. In the wake of these worries, Pete was conspiring behind the scenes to make certain that oral history would continue at Berkeley. He was a good friend of long-time Bancroft Library director Charles Faulhaber. When Faulhaber retired in 2011, Pete paid tribute to his friend’s leadership of Bancroft by creating the Charles B. Faulhaber Endowment, whose income was to be dedicated to the oral history program. Pete had only one request: that the name of the office be changed. Happily, the staff of the center recognized that we had long ago outgrown the “regional” in our former name and readily embraced the new moniker of the “Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library.”

Other than the name change, Pete asked for nothing in return for creating the Faulhaber endowment, which was built with his donations and those of many of his friends and venture capital colleagues. This endowment has been critical to the recent success of this office. Because only one of eight full-time staff positions, and none of the related costs of conducting interviews (equipment, transcription, travel), is paid for by the university, all of our projects require external funding. However, project funds can only support project-related activities and there is a lot more that we do — and want to do — than just conducting interviews, transcribing them, and editing them. Pete Bancroft’s “Charles Faulhaber Endowment” allows the Oral History Center to do so much more: we can host formal and informal training for those who want to learn oral history methodology from our highly-skilled team of historians; we can now create interpretative materials based on the interviews that we conduct, including, now, three seasons of our in-depth podcast series, “The Berkeley Remix”; and, perhaps most importantly, the Faulhaber endowment allows us to conduct research and development in support of new projects. We are fortunate to have a smart, ambitious, and creative group of oral historians who come up with potentially important project ideas; this endowment gives us the ability to pursue those ideas by doing background research, conducting pilot interviews, and seeking funding to make these ideas a reality. Thus, Pete Bancroft continued his career in venture capital with the Oral History Center: by providing perpetual seed funding, he has established a lasting legacy of innovation, experimentation, and entrepreneurship among the publicly-engaged scholars at the center!

In his final months of life, Pete Bancroft continued to think about and look after his friends, including the Oral History Center. Charles Faulhaber, returning the honor given to him by Pete, created the “Pete Bancroft Endowment for the Oral History Center,” with an initial gift from Pitch Johnson and additional gifts from many of the same philanthropists who supported the earlier one as well as his ‘Hill Billies’ campmates at the Bohemian Club. And like the Faulhaber endowment, this one will support the ongoing work on the Oral History Center. In a touching note just after Pete’s passing, Faulhaber let me know that Pete was thinking of us until the end, making a major donation to the endowment in the final weeks of his life. With this news, we sadly bid farewell to an esteemed and gracious benefactor — our angel investor.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director of the Oral History Center

OHC Director’s Column, November 2018

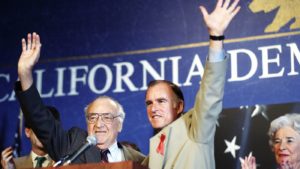

The Oral History Center is excited to announce that we have joined forces with local public radio station KQED on a significant new partnership. The occasion for this collaboration is a new oral history of four-term California governor Jerry Brown. The project is expected to encompass at least 30 hours of conversations with Brown, taking place over a series of months, beginning later this year. The interviews will span most of Brown’s adult life, including his time in the seminary, lessons learned from his father’s governorship, his terms as secretary of state, attorney general and governor of California, and mayor of Oakland, and three presidential bids. They will address a life lived in and out of the public eye, and a long and extraordinary career devoted to public service.

Research and interview duties will be shared by my colleague, Todd Holmes, and I. We’ll be joined by Scott Shafer, senior editor for KQED’s Politics and Government Desk and co-host of the weekly radio program and podcast Political Breakdown. “Jerry Brown is a singularly important figure in California political history,” Shafer says. “His long and remarkable time in and out of public life in California, including his personal reflections and insights, should be documented for posterity, and we’re delighted to be a part of doing just that.”

The final interviews will join our collection of political oral histories, which include major interview projects on four earlier California governors, including Jerry’s father Pat Brown, who was elected in 1958 and again in 1962. Transcripts and audio and video of the Brown interviews will be made available on our website. We are thrilled to partner with KQED to see that Governor Brown’s oral history is completed and made available to everyone — and we are humbled to be the ones with the honor of making sure that this history is recorded and preserved.

Like all Oral History Center projects, we are obliged to raise funding to help support this endeavor as neither the state or the university will provide funding this extraordinarily important project. We are happy to accept donations large and small for those who agree that this oral history needs to be recorded and that we cannot miss this window of opportunity to get it done. Please contact me directly (mmeeker@berkeley.edu or 510-643-9733) with questions or think about making a donation online: http://ucblib.link/givetoOHC

Martin Meeker, @MartinDMeeker

Charles B. Faulhaber Director

Oral History Center

New Release Oral History: Marshall Krause, ACLU of Northern California Attorney and Civil Liberties Advocate

The Oral History Center is pleased to release our life history interview with famed civil liberties lawyer, Marshall Krause.

Marshall Krause served as lead attorney for the ACLU of Northern California from 1960 through 1968 and subsequently served as an attorney in private practice where he continued to work civil liberties cases. Krause attended UCLA as an undergraduate and graduated from Boalt Hall, UC Berkeley School of Law after which he clerked for Judge William Denman and Justice Phil Gibson.

In this oral history, Mr. Krause discusses: his upbringing and education, including his time at Boalt Hall; clerkships with judges Denman and Gibson and how those experiences influenced his progressive political outlook; his tenure as ACLU staff attorney, including many of the cases he worked; his experiences arguing several cases before the United States Supreme Court; his perspective of the San Francisco counterculture of the 1960s; and his professional and legal career after leaving ACLU in 1968, which included arguing additional cases before the US Supreme Court.

This oral history is significant for any number of reasons, but it is especially worthwhile for anyone interested in the current state of battles around the freedom of speech — from obscenity through political speech — and how these were decided in the courts in decades past, establishing the precedents under which we live today.

Martin Meeker

From the Oral History Center Director – OHC and Education

For an office that does not offer catalog-listed courses, the Oral History Center is still deeply invested in — and engaged with — the teaching mission of the university.

For over 15 years, our signature educational program has been our annual Advanced Oral History Summer Institute. Started by OHC interviewer emeritus Lisa Rubens in 2002 and now headed up by staff historian Shanna Farrell, this week-long seminar attracts about 40 scholars every year. Past attendees have come from most states in the union and internationally too — from Ireland and South Korea, Argentina and Japan, Australia and Finland. The Summer Institute, applications for which are now being accepted, follows the life cycle of the interview, with individual days devoted to topics such as “Project Planning” and “Analysis and Interpretation.”

In 2015 we launched the Introduction to Oral History Workshop, which was created with the novice oral historian in mind, or individuals who simply wanted to learn a bit more about the methodology but didn’t necessarily have a big project to undertake. Since then, a diverse group of undergraduate students, attorneys, authors, psychologists, genealogists, park rangers, and more have attended the annual workshop. This year’s workshop will be held on Saturday February 3rd and registration is now open.

In addition to these formal, regularly scheduled events, OHC historians and staff often speak to community organizations, local historical societies, student groups, and undergraduate and graduate research seminars. If you’d like to learn more about what we do at the Center and about oral history in general, please drop us a note!

In recent years we have had the opportunity to work closely with a small group of Berkeley undergrads: our student employees. Although the Center has employed students for many decades, only in the past few years have they come to play such an integral role in and make such important contributions to our core activities. Students assist with the production of transcripts, including entering narrator corrections and writing tables of contents; they work alongside David Dunham, our lead technologist, in creating metadata for interviews and editing oral history audio and video; and they partner with interviewers to conduct background research into our narrators and the topics we interview them about. With these contributions, students have helped the Center in very real, measurable ways, most importantly by enabling an increase in productivity: the past few years have been some of the most productive in terms of hours of interviews conducted in the Center’s history. We also like to think that by providing students with intellectually challenging, real-world assignments, we are contributing to their overall educational experience too.

As 2017 draws to a close, I join my Oral History Center colleagues Paul Burnett, David Dunham, Shanna Farrell, and Todd Holmes in thanking our amazing student employees: Aamna Haq, Carla Palassian, Hailie O’Bryan, Maggie Deng (who wrote her first contribution to our newsletter this issue), Nidah Khalid, Pilar Montenegro, Vincent Tran, and Marisa Uribe!

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director of the Oral History Center