Tag: avant-garde art

Senga Nengudi: Black Avant-Garde Visual and Performance Artist

As a continuation of our work for the Getty Research Institute’s African American Art History Initiative (AAAHI), Dr. Bridget Cooks and I conducted several oral history interviews with the avant-garde artist Senga Nengudi. This interview is one of several AAAHI oral histories exploring the lives and work of Los Angeles-based artists, and highlights Nengudi’s contributions to visual and performance art.

Senga Nengudi is an avant-garde artist best known for her abstract sculpture and performance art. Nengudi was born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1943 and moved to Los Angeles, California, at a young age. She attended California State University, Los Angeles (CSULA) for both her undergraduate and master’s work, as well as completed a program at Waseda University in Tokyo, Japan. Nengudi was active in the avant-garde Black art scenes in Los Angeles and New York during the 1960s and 1970s, and was a member of the Studio Z Collective. She is best known for her R.S.V.P. (Répondez s’il vous plaît) Series featuring pantyhose, which she began in 1975. Nengudi is the recipient of many awards, including the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Award in 2005, the Anonymous Was a Woman Award in 2005, the Denver Art Museum Key Award in 2019, and was elected as a member to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2020. Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Senga Nengudi was still in elementary school when she and her mother moved to Los Angeles in the early 1950s. Despite a brief stint in New York, for more than thirty years she lived in the greater Los Angeles area first as a child; as a student at CSULA; as an artist and active member of the Studio Z Collection; and as a young mother. That Nengudi called Los Angeles home for so long meant that her formative years of creative expression and early artistic networks sprang from the Southland.

Looking back, Nengudi credits her mother with providing a creative foundation.

“…she was very, very, very conscious of the home and making something home, and so she would decorate the house. And then, say like three years later, she would repaint the walls, she would change the upholstery, she would do all those kinds of things. She was very aesthetically aware, as well as needed a particular beauty in her home to feel good.”

And Nengudi expressed her own creativity through several outlets, remembering, “It’s always been a deal between art and dance with me…” Indeed, during her undergraduate years at CSULA, she chose to major in art and minor in dance—a pairing which supports much of her work.

In the mid-1970s, Nengudi found an outlet to express her love of performance through the Studio Z Collective—a collective of artists interested in improvisation that continued into the 1980s. In addition to Nengudi, Studio Z was comprised of Houston Conwill, David Hammons, Maren Hassinger, and occasionally other artists including Franklin Parker and Ulysses Jenkins. Her relationships with these artists also had a great impact on Nengudi’s artistic career. Thinking of Studio Z’s contribution to her 1978 performance Ceremony for Freeway Fets, which took place under a freeway overpass on Pico Blvd., she muses that “we all kind of supported each other in our efforts.”

Nengudi also found early support from Los Angeles-based gallery owners like Greg Pitts at the Pearl C. Woods Gallery, as well as Brockman Gallery’s Alonzo and Dale Davis. In fact, Brockman Gallery’s dispersal of CETA [Comprehensive Employment and Training Act] funds helped employ artists like Nengudi and Maren Hassinger.

Hassinger remains Nengudi’s longtime creative collaborator. Nengudi recalls that the connection between the two was immediate, “We just kind of instantly became friends, because there was this commonality. She was involved with dance, she was involved with sculpture, all that kind of stuff.” And to why this collaboration with Hassinger has sustained both the passing of years and geographical distance, Nengudi explains:

“Because we believe so much in collaboration. We believe in unity. We believe in bringing the best out in each other…Even though our background is different, our interests are the same. It’s always been dance, performance, sculpture, movement, and this commitment to our art. And when we had some really funky times and we were 2,000 miles apart, the thing that held us together was this commitment to art. And so that kind of carried us through the most difficult things…So all these life events were going on, but the constant was our ability to connect and think and make happen.”

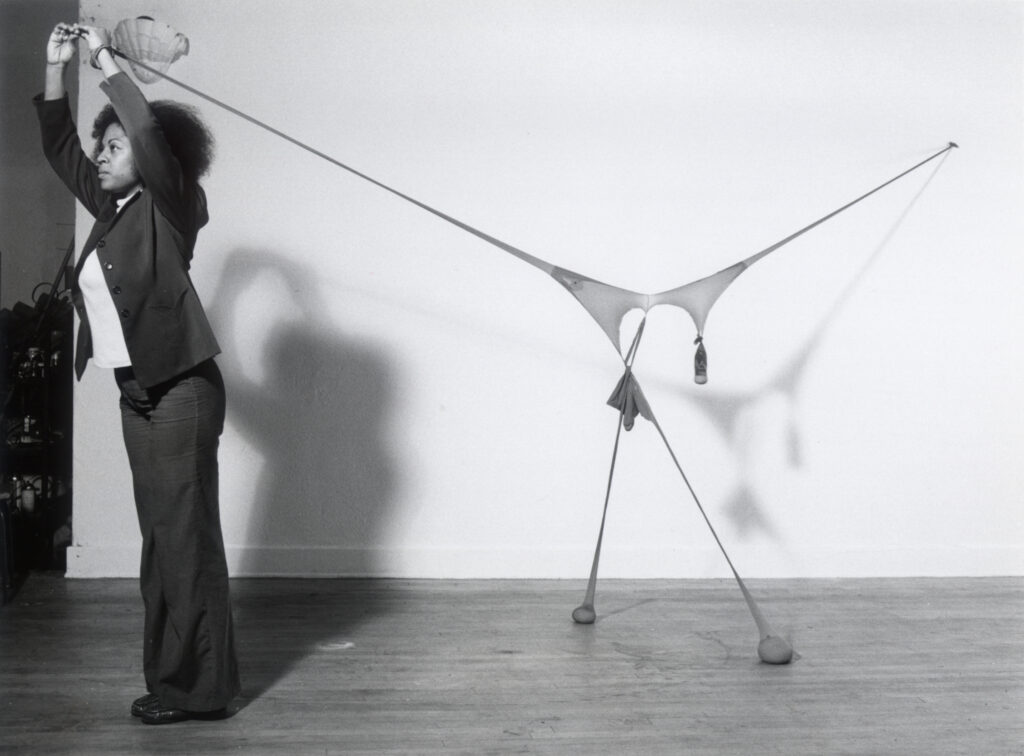

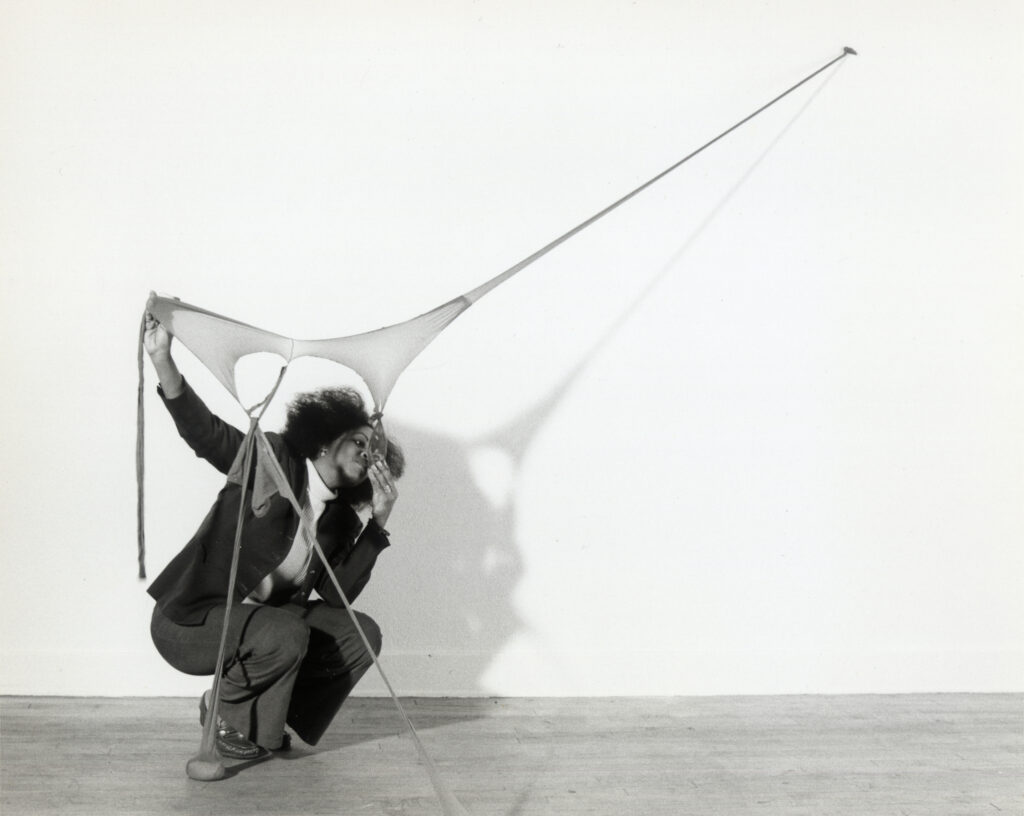

Nengudi’s most recognizable series of work is R.S.V.P., which she started in the mid-1970s. The R.S.V.P. Series, or Répondez s’il vous plaît (respond, please), demonstrated Nengudi’s experimentation with nylon pantyhose. Importantly, Nengudi began working in this medium after the birth of her first son, when she was especially interested in the elastic nature of a woman’s body. She recalls,

“So yes, the explorations were really exciting. I put eggs in them, I broke eggs in them…I used white glue, I used hot glue, which obviously didn’t last that long. I tried everything—resin. Again, it dissolved in the resin. So really, as I was developing the series, it was all about exploring the material…And it took a while to get to…the sand, where I just noticed that…once in the nylons, it had such sensuality to it, because it had this kind of natural body form from the weight of the sand.”

Given the experimental nature of her sand-filled nylon pieces, Nengudi explains, “I thought about them as sculpture first. I did not develop them thinking that I would perform in them.” But Nengudi eventually did embrace the performative potential of these sculptures, even engaging Hassinger to perform with them at the Pearl C. Woods Gallery in 1977 by entwining her body with the material, manipulating it, even dancing with it.

Nengudi has lived in Colorado since the 1980s, and continues to stimulate audiences by creating work that plays with the line between sculpture, installation, and performance in space. However, she has also made significant contributions as an arts educator, especially at University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, and as an advocate of the arts. Namely, she established a community art gallery called ARTSpace in Colorado Springs so that “artists could show their work” and learn “what it takes to have an art exhibit.” The added bonus, of course, was that “the community could come in and see the artwork. It was right there for them.” For someone whose early exposure to creative expression was so formative to her artistic practice, this is a logical next step to engage new generations of artists and viewers. It also connects with her decades-long entreaty to audiences: “respond, please.”

To learn more about Senga Nengudi’s life and work, check out her oral history interview! Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.