Tag: uc berkeley

Luella Lilly: Cal’s first and only Director of Women’s Athletics

By William Cooke

In 1976, Luella “Lue” Lilly became the first and only athletic director of the newly created Women’s Intercollegiate Athletic Department at Cal. Over the course of her 17-year tenure, eight of the women’s sports programs won a combined 28 conference championships. In 1989, USA Today ranked Cal’s women’s athletics program number four overall in the nation. Today, several women’s programs are consistently among the best in the country and Cal female athletes, former and current, compete in the Olympic Games.

Now one of the premier destinations for elite female student athletes, Cal has come a long way from being one of the last universities in the country to create a women’s athletics department and offer scholarships to female athletes. That history starts with Lilly.

You don’t try to keep up with Joneses. You figure out where the Joneses are going to go and get there before they do. And that was my philosophy. —Luella Lilly

Lilly had a steep mountain to climb when she first arrived at Berkeley. Ongoing budget constraints, competition over the use of limited sports facilities, and tensions between departments meant that she could not fight every battle all at once. Her wisdom and guidance set up women’s athletics for a successful future. Lilly’s oral history, conducted by the UC Berkeley Oral History Center in 2010, describes when and how Lilly picked her battles.

Playing catch up

Cal hired Lilly in 1976, four years after Title IX was signed into law by President Richard Nixon. The law prohibited discrimination on the basis of sex at any institution receiving federal aid. Lilly recalls that the newly founded Women’s Intercollegiate Athletics Department had a lot of catching up to do in regard to providing women with equal athletics opportunities. According to Lilly:

Cal was the last major university in the United States to give an athletic scholarship to women. They gave scholarships after I arrived, and there were no scholarships prior to my arrival. And most of the schools—some of them gave them prior to ’72 and others—the majority of the schools, if they weren’t giving scholarships when Title IX went in, they gave some scholarships right away.

It was only in the fall of 1977 that Cal’s first batch of female recruits came to campus. Among them were Colleen Galloway, who held the record for career points in Cal Women’s Basketball history until 2019, and standout three-sport athlete Sheryl Johnson, who played in three Olympic games for USA field hockey.

In her first year at the helm, Lilly prioritized providing scholarships for a few reasons. In her oral history, Lilly explains that the Women’s Sports Foundation published a booklet annually that listed which schools provided scholarships in each sport. The department needed scholarships in order to compete for the best recruits, of course. But to be recognized nationally as a school that provided scholarships was just as important.

I also knew that when it [the Women’s Sports Foundation booklet] came out in February, that Cal would not be included or it wouldn’t say anything… Talking with [Vice Chancellor] Bob Kerley—[I] told him that we could jumpstart a full year if we could get some money to get the scholarships… and then when that little form came out I could check [it]. And so what I did was—they gave me—I think it’s $6,740 dollars, which was—tuition and fees were $670, I think they were, something like that. Anyway, it gave me ten tuition and fees at that point in time. So I gave them to each of the sports that could give scholarships, and had the coach divide it so that whatever way they wanted to—if they wanted to give somebody a full ride that was up to them, but if they wanted to split it among all—they could do anything they wanted to in their particular sport. But I just wanted to be able to mark the check that said we had them.

The money needed to provide scholarships and pay coaches—both of which are necessary in order to build a successful athletic program—would not and did not appear out of thin air. Lilly says in her oral history, “With fundraising we’ve—I think we’ve done most everything anybody has done in fundraising.” Even so, early fundraising results were disappointing.

One thing that really backfired and really, really surprised us was that we had Bruce [now Caitlin] Jenner and Steve Bartkowski play a demonstration tennis match—and it was five bucks to get in and all this sort of thing, and this was right after Jenner had won the Olympic decathlon, and we just assumed that everybody would really, really come. And nobody—we had so few people that we went up to the department and asked all the staff to please come down to put some more people in the stands. And we opened the gates and just let anybody that wanted to come, to come in to look for it, because it was so embarrassing how few came. And the thing I remember us saying too, that was probably with Chris Dawson. “You know, if this was a fundraiser for the men, the thing would be full.”

Support and strife

Ironically, men involved in Cal Athletics, including boosters, administrators, and journalists, were some of Lilly’s biggest supporters as well as her biggest adversaries. Lilly describes an environment of contentiousness over the scheduling of limited athletics facilities between the four athletics departments: Physical Education, Recreational Sports, Men’s Athletics, and Women’s Athletics. She believed that sometimes the tensions were understandable given Cal’s limited number of facilities; but, at other times, the competition between departments felt totally contrived.

A lack of cooperation meant that Lilly’s women’s programs had to deal with last-minute facilities scheduling changes, as well as explicit efforts to block cooperation between the men’s and women’s athletics departments. Lilly had to decide whether to resist those efforts or focus her energies elsewhere. Oftentimes she wavered between the two:

I think that cooperation is the main thing. I think you can really, really help each other… One of the things that I did do here was that I had all of my coaches and athletes give gold cards to all of their counterparts. I think the men’s gymnastics team should be able to watch the women’s gymnastics team free of charge, so I did that. And then [Vice Chancellor for student affairs] Bob Kerley talked to me and said that—here we go again—that [Men’s Athletic Director] Dave Maggard was upset with it, that we were trying to get tickets for the men’s events, and he went on and on about what I was trying to do, so I said to Bob, “All right. We won’t do it.” So then I came back the next year and I said, “I am not comfortable with this. I don’t like the fact that we can’t cooperate and have the men come to the women’s events. I don’t even care if he just thinks we’re trying to increase our attendance. The point is that you’re working together.” Because again, I came from that background of when the swimmers were on the same buses and that sort of thing, in high school. So it’s really hard for me to just think that everybody is so territorial. So Bob [Kerley] said, “If you feel that strongly about it, just go ahead and do it and we’ll just put up with the consequences.” So I had my coaches do it the next year.

Some instances of antagonism seemed inexplicable to Lilly who, as a volleyball and basketball coach at the University of Nevada prior to her tenure at Cal, learned the value of cooperation between the men’s and women’s coaches.

I said, “Well, let’s try to have a Christmas party and get to know some of the male staff. So all my coaches invited all the men coaches to come to a Christmas party, and the Alumni House gave it to us for free. This is where I say I had a lot of cooperation—they gave us the room; we didn’t have to pay for it. And nobody showed up except for the men’s football staff. And Roger Theder said nobody’s going to tell him what party he could and couldn’t attend. And another coach had told me that Maggard threatened that if anybody came to this party they’d be fired. So here’s all the women’s staff and eight football coaches. And we had a good time, you know. But that was just it; it was one of those situations again that just didn’t make any sense for me. The tennis coaches should know each other, and all this sort of thing.

Although Lilly found some adversaries in other sports-related departments, she found supporters of Cal Athletics elsewhere. In her oral history, Lilly says that “the strongest supporters that we’ve had and the people that have helped us the most along the way have been men.”

Doug Gray, a reporter at The Daily Californian, took an interest in Cal Women’s Athletics and began covering Lilly’s programs. Members of Cal’s athletics boosters, the Bear Boosters, slowly warmed up to the idea of supporting Lilly’s department. But many were reluctant to openly support the Department, which made for some odd interactions with male boosters. As Lilly recalled:

When I used to give my speeches it was really kind of funny, because I said I felt like a hooker or something, because the guys would never just come out and hand me money. They always—as I was saying goodbye they would either slip it in my pocket or they would shake my hand and leave the money in my hand. Or do all these little indirect things so that nobody knew that they were giving us any money!

And so when we were doing that, this one guy said, “If you ever let anyone, anyone at any time, ever know that I gave to the women’s program, I will never give you another cent.” He’d given us a whole twenty-five dollars; you’d think he’d given us millions. Anyway, but then later on after it became the big deal to give—and one of the awards that he got—and he said he was one of the first members of the Bear Boosters contributing and helping Women’s Athletics. Because at that point in time it was acceptable to do it. So he went from one extreme to the other. So we laughed when we saw that on his resume.

Muddling through

Fundraising picked up eventually, but for quite some time Lilly had to make do with limited resources. Lilly recalls diving into dumpsters and upcycling waste into equipment that the women’s programs needed for competitions. Among other things, Lilly made tennis poles to hold up the nets for doubles, poles for cross-country finish lines and a rolling cart for outdoor sports out of scrap wood she salvaged.

The women’s head coaches, who were already underpaid at less than $5,000 a year, lacked adequate office space and had access to just three phones between the twelve of them. So Lilly, with help from administration, created an office space:

And what we did then was—and then Bob Kerley made arrangements for me to go down to the surplus area and to get some desks, because we didn’t even have desks for the coaches. So what we did was we put two desks together with one of the bathroom partitions for a wall. And then we just went down that whole great big area that we had and made little cubbyholes for the coaches. These things weren’t even attached; they were just between two desks. And then we cut out a hole at one end of them and made a little flap so you could put a telephone on it. And then the telephone was passed back and forth from one coach to the other for the various sports, so that there was a little platform for them to be able to put the telephone, but we only had three telephones. There were twelve sports.

At various points throughout her oral history, Lilly points to instances in which she might have made a very different decision but chose not to. For example, in the early 1980s, recruiting became even more competitive. Some recruits began to ask for free cars in exchange for their commitment, a request that she suspected other schools fulfilled. Lilly says she refused to give in, and her women’s programs lost out on excellent recruits as a result.

Similarly, when administration disallowed some women’s coaches from working under multiple departments at the same time, Lilly considered challenging the decision but ultimately chose not to.

They weren’t going to let the women coaches—for basketball, and Joan Parker for tennis—be able to be in our department and Physical Education at the same time. And yet at the same time, the wrestling, water polo, and tennis coaches and—a lot of them were coaching in the men’s sports and teaching— but I would have made a major men’s/women’s issue right at the very, very beginning, and I knew I had to get things established better than making that particular fight. So I didn’t fight with that particular issue, but I did go to Bob Kerley and say, “Since everything is in such turmoil right now, could we have a one-year extension on that particular issue?” So Joan Parker was able to coach tennis the first year, and Barbara Iten was able to coach basketball the first year that I was there, but with the idea that they would not be able to coach the next year because I would accept whatever their previous ruling was, because like I said, I wasn’t going to make that a major issue. I really had to tiptoe lightly, when I made an issue out of something and when I didn’t, and what things I let slip and which ones I didn’t, and where I took a really, really strong stand. And I had to try to think about what was best for women’s sports and then what was best for Cal.

Separate success

Even while Lilly had to grapple with some of the pitfalls of having separate mens and women’s athletic departments, she expresses discontent at the trend in collegiate athletics towards combining the departments. Cal Women’s Athletics merged with the men’s athletics department in 1992. Lilly points out that several women’s programs experienced a sudden downturn after the merger, dropping from national title contention year after year to irrelevance for quite some time. With separate leadership, Lilly argues, female athletes and women’s coaches are more well-represented. A single athletic director can’t represent everyone well.

I think a lot—again it has to do with leadership, and feeling that—you conveyed a lot of this to the recruits, that this was—you were in charge and this was what was going to happen, and so forth. And they could come and see [that a] woman is director at this time. I think it’s much more difficult, again, if you’ve got twenty sports, to pay the same amount of attention as you could get when you’ve got two leaders as opposed to one trying to do a bigger job… When they’re combined, I feel that anyone who would be in charge of a combined program would have the same difficulties. In other words, you are expected, for men’s football and basketball, no matter what, to be there. And yet, at the same time, you’ve got to try to balance all these other sports. But if you had—let’s say both [the men’s and women’s basketball] teams make it to the Sweet Sixteen, and you’re the athletic director, you know where you’re going to be.

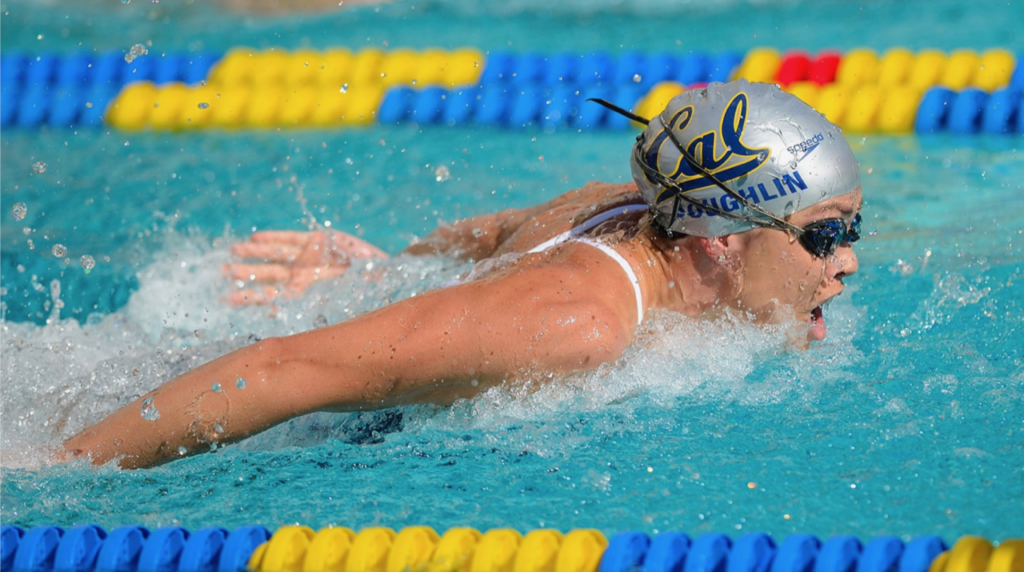

Lilly’s legacy was and is still visible in the form of elite Cal female student athletes and alumni. Natalie Coughlin, for example, swam for Cal in the early 2000s. She’s now a 12-time Olympic medalist, including three gold medals. Photo: UC Berkeley

With the merging of the men’s and women’s departments, Cal Athletics relieved Lilly of her duties. But 30 years later, Lilly’s legacy lives on in the form of elite women’s athletics programs. For progress to be made, Lilly hoped to predict the future and act quickly in order to stay one step ahead of other institutions. She managed the growth of coaching staff personnel and salaries with both budget constraints and trends in college athletics in mind, accelerating Cal Women’s Athletics’ rise to prominence.

There was a progression, but one of my favorite sayings which I think I made up myself is, “You don’t try to keep up with Joneses. You figure out where the Joneses are going to go and get there before they do.” And that was my philosophy. And so I always tried to figure out where sports were going, where were salaries going, where was the pressure going to be, and so forth, and then try to get all that into one big picture and then do what I could do within the money that we had.

More than 21 of the 45 oral histories in the Oral History Center’s Athletics at UC Berkeley project mention Lilly and her work.

Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, keyword, and several other criteria.

William Cooke recently graduated from UC Berkeley with a major in political science and a minor in history. In addition to working as a student editor for the Oral History Center, he was a reporter in the Sports department at UC Berkeley’s independent student newspaper, The Daily Californian.

Related Resources from The Bancroft Library

The Bancroft Library has hundreds of materials related to athletics in California and beyond. Here are just a few.

Lilly’s oral history is part of the Oral History Center’s project, Oral Histories on the Management of Intercollegiate Athletics at UC Berkeley: 1960-2014. This project comprises forty-five published interviews, conducted by John Cummins. Cummins was the Associate Chancellor and Chief of Staff who worked under UC Berkeley Chancellors Heyman, Tien, Berdahl, and Birgeneau from 1984 through 2008. Intercollegiate Athletics reported to Cummins from 2004 to 2006. Among the interviewees are longtime Chair of the Physical Education Department Roberta Park and former Assistant and Associate Athletic Director in the Women’s Athletic Department Joan Parker.

Articles based on this oral history project

William Cooke, “Title IX in Practice: How Title IX Affected Women’s Athletics at UC Berkeley and Beyond”

William Cooke, “Heavy hitters: the modern era of athletics management at UC Berkeley”

William Cooke: Luella Lilly: Cal’s first and only Director of Women’s Athletics

Other resources from The Bancroft Library

Cal women athletes hall of fame. Inauguration ceremony… May 24, 1978. Bancroft Library/University Archives. UC Archives ; 308m.p415.hf.1978

Cal sports 80’s. A program to improve the environment for Intercollegiate athletics at the University of California, Berkeley. Bancroft Library/University Archives. UC Archives ; 308m.p41.csp.1980

A celebration of excellence : 25 years of Cal women’s athletics. Bancroft Library/University Archives. UC Archives Folio ; 308m.p415.c.2001

About the Oral History Center

The UC Berkeley Oral History Center preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. You can find all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public.

Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Workshop Reminder — How to Publish Open Access at UC Berkeley on October 17, 2023

Date/Time: Tuesday, October 17, 2023, 11:00am–12:30pm

Location: Zoom only. Register via LibCal.

Are you wondering what processes, platforms, and funding are available at UC Berkeley to publish your research open access (OA)? This workshop will provide practical guidance and walk you through all of the OA publishing options and funding sources you have on campus. We’ll explain: the difference between (and mechanisms for) self-depositing your research in the UC’s institutional repository vs. choosing publisher-provided OA; what funding is available to put toward your article or book charges if you choose a publisher-provided option; and the difference between funding coverage under the UC’s systemwide OA agreements vs. the Library’s funding program (Berkeley Research Impact Initiative). We’ll also give you practical tips and tricks to maximize your retention of rights and readership in the publishing process.

Join us next week!

Virtual and in-person discussion on ethics in archiving

The UC Berkeley Oral History Center is proud to host a talk by oral historian Venkat Srinivasan, an alumnus of the 2014 Advanced Oral History Institute. Srinivasan invites us to imagine how we might construct a more inclusive, ethical, and accessible oral history archive.

Every archive accession brings with it questions about inclusivity, ethics and privacy. Please join the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library for a special guest presentation on ethics in the contemporary archive, by Venkat Srinivasan, archivist at the Archives at National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS) in Bangalore.

Tuesday, October 25, 11:30 a.m. – 1 p.m. Pacific Time.

In person in The Bancroft Library, Conference Room 267

Or join online via Zoom.

In his talk, “An Act of Imagination: The Archives as Commons,” Venkat Srinivasan—an alumnus of the Oral History Center’s Advanced Oral History Institute from 2014—invites us to imagine how we might construct a more inclusive, ethical, and accessible oral history archive. His presentation will address how questions of inclusivity, ethics and privacy are critical when an archive is just starting out, as is the case with the Archives at NCBS. Through examples from correspondence, oral histories, native digital files, its nascent accession and retention policies, and the challenge of a campus COVID-19 archive, this presentation will address the conflicts and synergies on rights to information, diversity, privacy, and the ethics of a contemporary archive.

The Archives at NCBS is a public collecting center for the history of science in contemporary India. It opened in 2019 and houses about 150,000 objects spread across 25 collections. The Archives at NCBS has one underlying philosophy: archives enable diverse stories. Through sharing the work that took place in 2020–21, this presentation will discuss four objectives for the archives: strengthening research collections and access in domain areas, pushing the frontiers of research in archival sciences, building capacity and public awareness through education, training and programming, and reimagining the archives as part of the commons. The Archives at NCBS is also part of Milli, a broader collective of individuals and communities interested in the nurturing of archives, and for the public to find, describe and share archival material and stories.

Speaker Biography

Venkat Srinivasan is the archivist at the Archives at NCBS in Bangalore. In addition, he currently serves on the institutional review boards for the archives at IIT Madras, ISI Kolkata, and NID Ahmedabad, and on the board of the Commission on Bibliography and Documentation of the IUHPST (International Union of History and Philosophy of Science and Technology). He is a member of the Encoded Archival Descriptions – Technical Sub-committee (Society of American Archivists), and Committee on the Archives of Science and Technology (CAST) of the ICA Section on Research Institutions (International Council on Archives). He is a life member of the Oral History Association of India (OHAI), and served in an executive role in OHAI between 2020 and 2022. He is a founding member of Milli, a collective of individuals and communities committed to the nurturing of archives. Prior to this, he was a research engineer at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford University. In addition, he is an independent science writer, with work in The Atlantic and Scientific American online, Nautilus, Aeon, Wired, and the Caravan. He graduated with a Masters in Materials Science from Stanford University (2005), a Masters in Journalism (science) from Columbia University (2009), and a Bachelors in Engineering from the University of Delhi (2003).

In-person directions and Zoom details

Zoom details

Please be sure to sign into a Zoom account (free, institutional, or paid).

Join Zoom Meeting

https://berkeley.zoom.us/j/97008598387

Meeting ID: 970 0859 8387

One tap mobile

+16699006833, 97008598387# US (San Jose)

In-person directions

Through the main entrance of The Bancroft Library, go straight. Once you pass the museum on your right, the Conference Room 267 is the first door on your left. This room is wheelchair accessible.

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. You can find all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history.

Latinx Research Center (LRC) Faculty-Mentored Undergraduate Research Fellowship

Latinx Research Center (LRC) Faculty-Mentored Undergraduate Research Fellowship

LRC is excited to launch the LRC Faculty-Mentored Undergraduate Research Fellowship program, pairing outstanding faculty with outstanding undergraduate students to advance research in US Latinx Studies.

The LRC has been awarded $550K by the Office of Financial Aid & Scholarships for the next 5 years to support this program. Every year, eleven $10K awards will be made in the liberal arts, and across the professional schools and the museum, to support faculty-mentored undergraduate research fellows throughout a full year: two semesters and a summer. The first round of awards will begin as early as Spring 2022. However, research can also begin in the summer of 2022. The application period has been extended to February 16th. Awards for applications that met the original January 31st deadline will be announced on Monday, February 7th; awards for applications received by February 16th will be announced on February 23rd. The award jury will consist of senior humanities and social sciences professors and will be distributed equitably across disciplines.

Applications should be submitted by faculty, who will nominate an outstanding undergraduate student that has agreed to work with them. Faculty in earlier stages of their career will be favored, however, all faculty are encouraged to apply. Selected student fellows will receive the $10K award throughout the course of a year, and will work closely with their faculty mentor, assisting in research, and developing their research skills, critical thinking, and intellectual creativity. Student fellows and mentors will be expected to meet weekly or biweekly, and to discuss their research at the LRC at the end of the award cycle. As an outcome of this mentored research fellowship, under the guidance of their faculty mentors, students will develop their own honors or capstone thesis, art practice, or other projects.

To apply, please visit https://forms.gle/H4hy1oRJhm39G1KT9.

For questions, email latinxresearch@berkeley.edu.

JoAnn Fowler: Building the Foundations of SLATE

The Oral History Center has been conducting a series of interviews about SLATE, a student political party at UC Berkeley from 1958 to 1966 – which means SLATE pre-dates even the Free Speech Movement. The newest addition to this project is an oral history with JoAnn Fowler, who was a founding member of the organization in the late 1950s.

JoAnn Fowler is a retired Spanish language educator and was a founding member of the University of California, Berkeley student political organization SLATE in the late 1950s. Fowler grew up in Los Angeles, California. She attended UC Berkeley from 1955 to 1959, where she became active in SLATE and served in student government through Associated Students of the University of California (ASUC). After completing a master’s degree at Columbia University, she worked as a teacher, mostly in Davis, California. Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

I have previously written about the contributions of women members of SLATE and their sometimes complicated feelings about gender roles in this student political group. Fowler, however, did not feel that being a woman was not an obstacle for her in SLATE, and her interview includes memories of her own role in shaping the organization.

Fowler recalls being an outspoken SLATE member from the start. At her first meeting with the group in the fall of 1957, she recalled being overwhelmed by the advanced political theory many of the group discussed, and by one faction that she perceived “wanted to sit around and talk these things to death and not try to take any kind of action.” She felt that in order to be politically effective, the group had to take another approach:

I’m very verbal, I’m not shy at all, I speak right up, I don’t care, I have nothing to lose here. I say that, “You have to do something within the campus, you have to work within the campus. If you want to get all these things done, you have to get elected and do things on campus.”…So that’s the position I take, and that’s the position that Pat Hallinan takes, and so we win over the majority of these people…

Perhaps Fowler’s greatest contribution to the group was that in the spring of 1958 she ran for and won a position with ASUC on the SLATE ticket. This made Fowler and Mike Gucovsky the first SLATE members to have a voice in student government at UC Berkeley, and being able to affect progressive political change from positions of campus leadership was a key goal of the group. In speaking of her campaign platform, Fowler remembered:

If you were to name anything, we ran on all of it, but not all of that could be addressed during the campaign. Basically, it was: freedom of speech was addressed through [being] against the [House] Un-American Activities Committee and also by the relationship between professors and the students that should be confidential and the anti-Loyalty Oath. Then there was civil liberties in the South; in Berkeley with that housing ordinance that came up for vote; and on the campus that no fraternity or sorority should discriminate.

She continued discussion of that ASUC campaign, saying:

This was encouraged by Mike Miller. I didn’t mind running—that was going to be great—but I did mind speaking to big groups. I hadn’t had a lot of experience doing that, so he encouraged me to do that. I went around only two nights that I remember, and it was only to men—I never spoke to women—and only at the co-ops. That was my background; I’d come out of co-ops. I’d go in at dinnertime and I would speak for two minutes, maybe somebody introduced me and maybe somebody didn’t. I’d speak for two minutes to those very immediate concerns that I thought would be very appealing, and I would have this overwhelming applause. But I felt that anybody, any woman could have stood up there and gotten this overwhelming applause, because that’s the kind of applause I felt it was. I don’t know, maybe that’s just me. I don’t know who else spoke there. I don’t know if men spoke there, if other independents have reached out, I have no idea.

Even after she graduated from UC Berkeley in 1959, the lessons she learned from SLATE stayed with her. While living in Davis, she worked at a Hunt’s tomato factory, where she attempted to organize the office workers. Later, she headed the Davis Teachers Association, supporting a raise in teachers’ salaries. These organizing efforts didn’t always succeed, but Fowler saw them as part of a larger political project she’d been passionate about since her time in college. She explained, “But I did my bit, and so without SLATE, I wouldn’t have…tried, no, I wouldn’t have tried.”

Reflecting on how her involvement with SLATE impacted her life, Fowler observed:

I think it was one of the greatest experiences of my life. I never would have been as politically aware. I didn’t have that background, I didn’t take political science, I didn’t take sociology; I took economics, I took psychology. I never would have been as aware or as active as I was, I wouldn’t have had a group. When I lived in an apartment, I didn’t have a social group or I didn’t have—you were going to come on campus and leave campus because you certainly didn’t meet too many people coming out of that lecture hall of 500 people. I’m glad I have that experience, very much so. It was a good time in my life.

To learn more about JoAnn Fowler’s life and political work, check out her oral history! Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Online exhibit: First 50+ years of the Campus & City

Take a look at the virtual exhibit from the Earth Sciences & Map Library, titled “First 50+ years of the Campus & City: Explore Cal and the City of Berkeley with Oski from 1860-1920!” The exhibit pulls together a range of multi-media materials, including photographs, video, maps (of course!), and even an interactive game, for a light-hearted exploration of the early years of the campus and city. This blog post explains how the exhibit was created using Esri’s StoryMaps platform.

Resource: UC Berkeley Library’s Digital Collections

The Library has launched a platform for its growing collection of digitized materials. It currently includes more than 92,000 items from more than 200 collections that are available to be viewed at any time, from anywhere. Read more about the project in this Daily Cal article.

The Library has launched a platform for its growing collection of digitized materials. It currently includes more than 92,000 items from more than 200 collections that are available to be viewed at any time, from anywhere. Read more about the project in this Daily Cal article.

Women of SLATE: Susan Griffin and Julianne Morris

The Oral History Center has been conducting a series of interviews about SLATE, a student political party at UC Berkeley from 1958 to 1966 – which means SLATE pre-dates even the Free Speech Movement. The newest additions to this project include two women who joined SLATE in the early 1960s at a tumultuous time at UC Berkeley: Susan Griffin and Julianne Morris.

Susan Griffin is an accomplished writer, and was a member of the UC Berkeley student political organization SLATE in the early 1960s. Griffin grew up in Los Angeles, California. She attended UC Berkeley, where she became active in SLATE, attending protests and engaging in political discussions. Griffin left Berkeley in 1963, but continued to work as a writer in the San Francisco Bay Area, producing many works, including Woman and Nature: The Roaring Inside Her. Over the years, Griffin remained active in causes of social justice, including the women’s movement and anti war protests.

Julianne Morris is a former social worker and mediator, and was a member of the UC Berkeley student political organization SLATE in the early 1960s. Morris grew up in Compton, California, and attended UC Los Angeles, where she helped found the student political group PLATFORM based on discussions with SLATE members. She then transferred to UC Berkeley, where she became active in SLATE, attending protests and running for ASUC student representative. Morris stayed at UC Berkeley to earn her master’s in social work. She then moved to New York City in 1964 and was a social worker for many years, where she helped start women’s centers, rape crisis programs, and became a part of the women’s movement. She returned to Berkeley in the early nineties and reconnected with former SLATE friends through reunions and an ongoing political discussion group.

Griffin and Morris were among the second generation of SLATE activists and joined the group around the same time in 1960 – after the famous HUAC protest in May of 1960 and before the Free Speech Movement in 1964. They also have similar upbringings in Jewish (adoptive family, in Griffin’s case) and politically left families who feared encroaching McCarthyism. These backgrounds helped ignite a political consciousness in both women that led them to SLATE.

Griffin and Morris’s oral histories build on an archive of SLATE history, but they also speak specifically to their experiences as women in this group. Both recount instances of feeling marginalized as women, of being left to do the “scut work” like mimeographing and cooking for hungry activists. They even recount tensions at a 1984 SLATE reunion in which those newly empowered by feminism expressed displeasure with the way they had been treated; many of the men denied this discrimination, but others took it to heart and sincerely apologized. And yet, Griffin and Morris both were encouraged to run for ASUC office in the early 1960s, campaigning on the SLATE platform and often pushing their own boundaries of what they thought was possible. Despite the challenges of being a woman in this campus political group, there were still opportunities to grow as individuals and as leaders.

Listen as Susan Griffin and Julianne Morris share their memories of running for ASUC on the SLATE ticket at UC Berkeley:

Even though both Griffin and Morris had decreased participation in SLATE or left campus by 1964, their experiences in the organization clearly shaped their perspectives about politics and activism, particularly as they both became involved with the women’s movement. Griffin explained, “The guys may not have known it, but they were training feminist activists in all that period.”

Most importantly, by recalling their times with SLATE and later political work, both Griffin and Morris emphasized the importance of building and sustaining community in activist groups. For Morris, joining SLATE helped her find a place where she belonged. Griffin pointed to organizations of politically like-minded individuals as ways to create belonging and “joy” through an almost spiritual experience of protest.

Listen as Julianne Morris reflects on SLATE’s impact on the Free Speech Movement:

Come learn more about SLATE, and explore the oral histories of Susan Griffin and Julianne Morris!

Fall 2019: New books from Mexico

Welcome back from the long-deserved summer break! I wanted to share with you that during the summer break, the library has been as active as it is usually during the academic year. We have been purchasing books to prepare for the new academic year. Below is the album of some new recently purchased books from Mexico for your consideration. Please click on the photo below to get access to the individual images of the new books from Mexico.

From the Archives: C. Judson King

“Freeze-Dried Turkey, Food Tech, and Futures”

by Caitlin Iswono

Caitlin Iswono is a sophomore undergraduate student at UC Berkeley majoring in chemical engineering. In the Spring 2019 semester, Caitlin worked with historian Roger Eardley-Pryor of the Oral History Center and earned academic credits as part of UC Berkeley’s Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program (URAP). URAP provides opportunities for undergraduates to work closely with Berkeley scholars on the cutting edge research projects for which Berkeley is world-renowned. Caitlin provided valuable research for Eardley-Pryor’s science-focused oral history interviews this past semester. Caitlin’s explorations of the Oral History Center’s existing interviews resulted in this month’s “From the Archives” article.

“I had my turkeys. I think I may still have a piece of freeze-dried turkey that’s now fifty years old.”

— C. Judson King, “A Career in Chemical Engineering and University Administration, 1963-2013,” oral history interviews conducted by Lisa Rubens and Emily Redman, with Sam Redman, in 2011, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2013.

In 1963, at age 29, C. Judson “Jud” King was backpacking in California when a fellow Boy Scouts Master revealed he freeze-dried his food before weeklong trips to the Sierra Mountains with groups of ten to twelve people. While the levels of safety and sanitation were not like today’s freeze-dried food, this period in King’s early adulthood sparked a branch of his later academic research that opened new discoveries and advancements in the food-technology industry. Like King’s connection with hiking and freeze-drying, I also aspire to coalesce my personal interests—namely, in humanitarian aid—with research in food technology for my future career.

King, a professor emeritus of UC Berkeley’s Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, held positions in a wide variety of academic and administrative posts. Throughout his career, King served as the Provost and Senior Vice President of Academic Affairs of the University of California system, as Dean of the College of Chemistry at UC Berkeley, and as Chair of Berkeley’s Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering. With over 240 research publications, including a widely used chemical engineering textbook, 14 patents, and major awards from the American Institute of Chemical Engineers, King has lived an accomplished life. But how did he get started in chemical engineering? And what might a chemical engineering student like me take from his experiences?

When asked in his 2011 oral history interview why he chose chemical engineering, King simply answered “I like chemistry. I like math. What should I look to major in college? The answer was chemical engineering.” King’s statement rings true for me, too. As an incoming freshman to Berkeley in 2017, I knew I would major in chemical engineering, but I was unsure what I wanted to do with this degree. In Cal’s rigorous chemical engineering program, I occasionally lost sight of the bigger picture. Constant midterm cycles, weekly problem sets, daily academic tasks, and my broader student activities all made it easy to avoid exploring why I’m pursuing my chemical engineering degree and what I hope to accomplish with it. However, learning from the experiences and insights of upperclassmen, graduate instructors, and my professors, I’ve found new purpose and aspirations for my future.

Not unlike King, I also became interested in food technology. My interest in food-tech began after attending Berkeley’s on-campus UNICEF Club and hearing guest lectures on the profound effects advanced food technology can have for developing countries. UNICEF is a United Nations organization charged with protecting children’s rights and helps over 190 disadvantaged territories around the world. It does so, in part, by incorporating food science and technology in their efforts to assist malnourished children, particularly with Ready to Use Therapeutic Foods (RUTF). Learning about this advancement sparked my interest in food science, similar to how hiking inspired King’s research transition to freeze-drying foods. King’s successful research and collaborations with companies such as Proctor and Gamble opened my mind to new possibilities. Reading King’s oral history interview and discovering his experiences in diverse fields within chemical engineering provided guidance on a possible career path for me.

King’s oral history also offered insight on different processes of freeze drying and how they influenced history. As King explained it, the development of freeze-dried techniques did not emerge from a desire for portable food. Rather, it arose from efforts to preserve medicines and blood plasma cells for medical reasons, particularly from isolating and stabilizing penicillin during World War II. Only after World War II ended did industries utilize freeze-drying to preserve foods. Industrial processors and academics like Jud King realized that freeze-drying techniques could apply to many fields, whether for military use, backpacking, space travel, or pharmaceuticals. These realizations have since inspired me to combine my passions for UNICEF advocacy and food technology to positively impact underdeveloped countries.

King’s interview reminded me that every person starts from somewhere and it’s okay to not have the entirety of life figured out from the very beginning. King’s interests in freeze-drying led to him becoming a renowned professor emeritus and former dean of Berkeley’s College of Chemistry. His story reminded me that the most anyone can do is strive to learn new things, try your hardest, and take on new opportunities. Your path and future track will then build itself.

— Caitlin Iswono, UC Berkeley, Class of 2021