Tag: UC Berkeley Oral History Center

The Oral History Center Presents the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project

The Oral History Center is proud to announce the launch of the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project, featuring 100 hours of oral history interviews with 23 Japanese American narrators who are survivors and descendants of two World War II-era sites of incarceration: Manzanar in California and Topaz in Utah. The majority of these oral histories are live on the Oral History Center website, where you can learn more about the project and the interviews themselves.

Just a couple of months after the United States entered World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. This order authorized the government to forcibly remove more than 120,000 Japanese American civilians—even American-born citizens—from their homes on the West Coast, and put them into incarceration camps shrouded in barbed wire and patrolled by armed guards for the duration of the war. This imprisonment uprooted families, disrupted businesses, and dispersed communities—impacting generations of Japanese Americans.

Even as the intergenerational impacts of World War II-era incarceration still touch many Japanese American descendants today, some Americans remain unaware of this history. It was in the spirit of illuminating the wounds of incarceration that OHC interviewers Roger Eardley-Pryor, Shanna Farrell, and Amanda Tewes embarked on this series of oral histories to record the stories of child survivors and descendants. Using healing as a throughline, these life history interviews explore identity, community, creative expression, and the stories family members passed down about how incarceration shaped their lives.

The project began in 2021 with funding from the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant. The interviews were conducted remotely via Zoom due to the global COVID-19 pandemic. The OHC team gathered a group of stakeholders with ties to the community to advise the project. Dr. Lisa Nakamura, a clinical psychologist who is herself a descendant of the Topaz incarceration camp, led Healing Circles for the project narrators after their interviews to process the experience without the interviewers present.

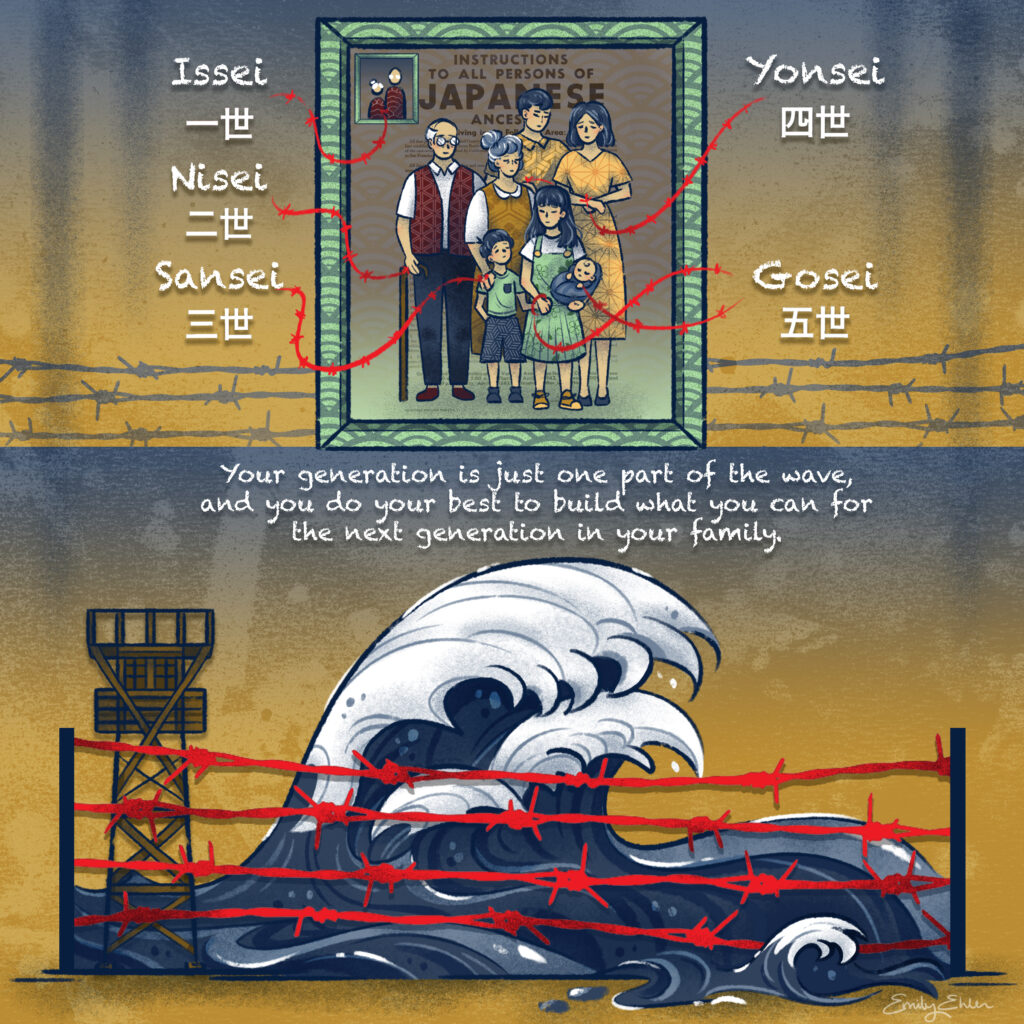

In addition to the oral histories, the OHC team produced a podcast as Season 8 of The Berkeley Remix to highlight the narrative themes that emerged from the interviews. They also commissioned artist Emily Ehlen, who created ten illustrations based upon stories and themes recorded in the interviews.

The podcast, “‘From Generation to Generation’: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration,” is a four-episode season featuring stories of activism, contested memory, identity and belonging, as well as artistic expression and memorialization of incarceration. It was produced by Rose Khor, Roger Eardley-Pryor, Shanna Farrell, and Amanda Tewes, and narrated by Devin Katayama. All four episodes are live on the OHC’s SoundCloud and in your podcast feeds.

Emily Ehlen’s artwork can be found on the OHC’s blog website and is available for download for educational purposes. Roger Eardley-Pryor sat down with Emily to learn more about her background, her work, and her process of creating these graphic illustrations.

Please explore the oral history transcripts and videos, listen to season 8 of The Berkeley Remix, and view Emily Ehlen’s artwork for more about the OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project.

A special thanks to the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant for funding this project.

The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government.

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you would like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. The Oral History Center is a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. As such, we must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

The Oral History Center Presents The Berkeley Remix Season 8: “‘From Generation to Generation’: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration”

Just a couple of months after the United States entered World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. This order authorized the government to forcibly remove more than 120,000 Japanese American civilians—even American-born citizens—from their homes on the West Coast, and put them into incarceration camps shrouded in barbed wire and patrolled by armed guards for the duration of the war. This imprisonment uprooted families, disrupted businesses, and dispersed communities—impacting generations of Japanese Americans.

In season 8 of The Berkeley Remix, a podcast of the Oral History Center at UC Berkeley, we are highlighting interviews from the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project. The OHC team interviewed twenty-three survivors and descendants of two World War II-era sites of incarceration: Manzanar in California and Topaz in Utah. This four-part series includes clips from these interviews, which were recorded remotely via Zoom. Using healing as a throughline, these life history interviews explore identity, community, creative expression, and the stories family members passed down about how incarceration shaped their lives.

This season features interview clips from the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project.

Produced by Rose Khor, Roger Eardley-Pryor, Shanna Farrell, and Amanda Tewes. Narration by Devin Katayama. Artwork by Emily Ehlen. A special thanks to the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant for funding this project.

The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Episode 1: “‘It’s Happening Now’: Japanese American Activism.” In this episode, we explore activism and civic engagement within the Japanese American community. The World War II-era incarceration of Japanese Americans inspired survivors and descendants to build diverse coalitions and become engaged in social justice issues ranging from anti-Vietnam War activism to supporting Muslim Americans after 9/11 to protests against the separation of families at the US-Mexico border. Many Japanese Americans also participated in the redress movement, during which time many individuals broke their silence about incarceration, and empowered the community to speak out against other injustices.

This episode features interviews from the Oral History Center’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, and includes clips from: Bruce Embrey, Hans Goto, Jean Hibino, Roy Hirabayashi, Susan Kitazawa, Kimi Maru, Margret Mukai, Ruth Sasaki, Nancy Ukai, and Rev. Michael Yoshii. Additional archival audio from Tsuru for Solidarity and the National Archives. The transcript from Sue Kunitomi Embrey’s testimony comes from the Los Angeles hearings from the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. To learn more about these interviews, visit the Oral History Center’s website.

Episode 2: “‘A Place Like This’: The Memory of Incarceration.” In this episode, we explore the history, legacy, and contested memory of Japanese American incarceration during World War II. Incarceration represented a loss of livelihoods, property, and freedom, as well as a disruption—cultural and geographic—in the Japanese American community that continued long after World War II. While some descendants heard family stories about incarceration, others encountered only silence about these past traumas. This silence was reinforced by a society and education system which denied that incarceration occurred or used euphemisms to describe what Japanese Americans experienced during World War II. Over the years, Japanese Americans have worked to reclaim the narrative of this past and engage with the nuances of terminology in order to tell their own stories about the personal and community impacts of incarceration.

This episode features interviews from the Oral History Center’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, and includes clips from: Miko Charbonneau, Bruce Embrey, Hans Goto, Patrick Hayashi, Jean Hibino, Mitchell Higa, Carolyn Iyoya Irving, Susan Kitazawa, Ron Kuramoto, Kimi Maru, Lori Matsumura, Alan Miyatake, Jennifer Mariko Neuwalder, Ruth Sasaki, Masako Takahashi, Peggy Takahashi, Nancy Ukai, and Rev. Michael Yoshii. Additional archival audio from the US Office of War Information and the Internet Archive. To learn more about these interviews, visit the Oral History Center’s website.

Episode 3: “‘Between Worlds’: Japanese American Identity and Belonging.” In this episode, we explore identity and belonging in the Japanese American community. For many Japanese Americans, identity is not only personal, it’s a reclamation of a community that was damaged during World War II. The scars of the past have left many descendants of incarceration feeling like they don’t wholly belong in one world. Descendants have navigated identity and belonging by participating in Japanese American community events and supporting community spaces, traveling to Japan to connect with their heritage, as well as cooking and sharing Japanese food. However, embracing Japanese and Japanese American culture can highlight for descendants their mixed identities, leaving them feeling even more like they have a foot in multiple worlds.

This episode features interviews from the Oral History Center’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, and includes clips from: Miko Charbonneau, Hans Goto, Jean Hibino, Roy Hirabayashi, Carolyn Iyoya Irving, Susan Kitazawa, Kimi Maru, Lori Matsumura, Alan Miyatake, Jennifer Mariko Neuwalder, Ruth Sasaki, Steven Shigeto Sindlinger, Masako Takahashi, Peggy Takahashi, Nancy Ukai, Hanako Wakatsuki-Chong, and Rev. Michael Yoshii. To learn more about these interviews, visit the Oral History Center’s website.

Episode 4: “‘Origami as Metaphor’: Creative Expression, Memorialization, and Healing.” In this episode, we explore creative expression, healing, and the memorialization of Japanese American incarceration. It is clear that stories about World War II incarceration matter. Some descendants embrace art and public memorialization about incarceration history as not only means of personal creative expression and honoring the experiences of their ancestors, but also as avenues to work through the intergenerational impact of this incarceration. Stories shared through art and public memorialization help people both inside and outside of the Japanese American community learn about the past so they have the tools to confront the present. Others seek healing from this collective trauma by going on pilgrimage to the sites of incarceration themselves, reclaiming the narrative of these places.

This episode features interviews from the Oral History Center’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, and includes interviews from: Miko Charbonneau, Bruce Embrey, Hans Goto, Patrick Hayashi, Jean Hibino, Mitchell Higa, Roy Hirabayashi, Carolyn Iyoya Irving, Susan Kitazawa, Ron Kuramoto, Kimi Maru, Lori Matsumura, Jennifer Mariko Neuwalder, Ruth Sasaki, Masako Takahashi, Nancy Ukai, Hanako Wakatsuki-Chong, and Rev. Michael Yoshii. Additional audio of taiko drums from Roy Hirabayashi. To learn more about these interviews, visit the Oral History Center’s website.

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you would like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. The Oral History Center is a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. As such, we must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

The Berkeley Remix Season 8, Episode 2:”‘A Place Like This’: The Memory of Incarceration”

In this episode, we explore the history, legacy, and contested memory of Japanese American incarceration during World War II.

Incarceration represented a loss of livelihoods, property, and freedom, as well as a disruption—cultural and geographic—in the Japanese American community that continued long after World War II. While some descendants heard family stories about incarceration, others encountered only silence about these past traumas. This silence was reinforced by a society and education system which denied that incarceration occurred or used euphemisms to describe what Japanese Americans experienced during World War II. Over the years, Japanese Americans have worked to reclaim the narrative of this past and engage with the nuances of terminology in order to tell their own stories about the personal and community impacts of incarceration.

In season 8 of The Berkeley Remix, a podcast of the Oral History Center at UC Berkeley, we are highlighting interviews from the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project. The OHC team interviewed twenty-three survivors and descendants of two World War II-era sites of incarceration: Manzanar in California and Topaz in Utah. This four-part series includes clips from these interviews, which were recorded remotely via Zoom. Using healing as a throughline, these life history interviews explore identity, community, creative expression, and the stories family members passed down about how incarceration shaped their lives.

This season features interview clips from the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project. This episode includes clips from: Miko Charbonneau, Bruce Embrey, Hans Goto, Patrick Hayashi, Jean Hibino, Mitchell Higa, Carolyn Iyoya Irving, Susan Kitazawa, Ron Kuramoto, Kimi Maru, Lori Matsumura, Alan Miyatake, Jennifer Mariko Neuwalder, Ruth Sasaki, Masako Takahashi, Peggy Takahashi, Nancy Ukai, and Rev. Michael Yoshii. Additional archival audio from the US Office of War Information and the Internet Archive. To learn more about these interviews, visit the Oral History Center’s website.

Produced by Rose Khor, Roger Eardley-Pryor, Shanna Farrell, and Amanda Tewes. Narration by Devin Katayama. Newsreel audio clip “Japanese Relocation” from the U.S. Office of War Information, ca. 1943, courtesy of Prelinger Archives. Newsreel audio clip “August 14, 1945, Newsreel V-J Day” from the Internet Archive. Original theme music by Paul Burnett. Additional music from Blue Dot Sessions. Album artwork by Emily Ehlen. A special thanks to the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant for funding this project.

The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government.

LISTEN TO EPISODE 2 ON SOUNDCLOUD

PODCAST TRANSCRIPT: “‘A Place Like This’: The Memory of Incarceration”

Newsreel from the 1940s: “When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, our West Coast became a potential combat zone. Living in that zone were more than 100,000 persons of Japanese ancestry. Two-thirds of them American citizens, one-third aliens. We knew that some among them were potentially dangerous; most were loyal. But no one knew what would happen among this concentrated population if Japanese forces should try to invade our shores. Military authorities therefore determined that all of them—citizens and aliens alike—would have to move.”

Jean Hibino: What would you carry? If everybody had two things they could carry, what would you put into a duffel bag? And what if you had a baby, and that’s one of the things that you’re carrying? How do you figure out the other thing? What is important to you? And you have no idea where you’re going, what kind of weather it’s going to be.

Theme song fades in.

Devin Katayam: Welcome to The Berkeley Remix, a podcast from the Oral History Center at the University of California, Berkeley. The Center was founded in 1953, and records and preserves the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world. You’re listening to our eighth season, “‘From Generation to Generation’: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration.” I’m your host, Devin Katayama.

This season on The Berkeley Remix, we’re highlighting interviews from the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project. The OHC team interviewed twenty-three survivors and descendants of World War II-era sites of incarceration at Manzanar in California and Topaz in Utah. In this four-part series, you’ll hear clips from these interviews, which were recorded remotely via Zoom. These life history interviews explore identity, community, creative expression, and the stories family members have passed down about how incarceration shaped their lives.

As a heads up, generational names for Japanese Americans are going to be important in this series. Issei refers to the first generation of Japanese immigrants to the United States. Nisei are the second generation, Sansei the third, Yonsei the fourth, and Gosei the fifth. Just think about counting to five in Japanese: ichi, ni, san, shi, go.

This is episode 2, “‘A Place Like This’: The Memory of Incarceration”

Theme song fades out.

Katayama: Executive Order 9066 changed life for Japanese Americans. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the order on February 19, 1942. It authorized the forced removal of Japanese American civilians from their homes on the West Coast. The federal government incarcerated Japanese Americans first in regional assembly centers before sending them to prison camps for the duration of the war. We’re talking about more than 120,000 people—or roughly the population of Topeka, Kansas.

Hibino: The US government was very careful about choosing how they wanted to describe the unconstitutional [laughs] removal of 120,000 people, uh, by just saying it was for their own safety, of military necessity: “It was a relocation. It was an evacuation for their own safety.” But we know better.

Katayama: That’s Jean Hibino, a Sansei whose family was incarcerated in Topaz. Nancy Ukai, a Sansei whose family was also imprisoned in Topaz, says she remembers the stories her mother shared about this time.

Nancy Ukai: The immigrants couldn’t buy land; they couldn’t naturalize; they couldn’t vote, so they didn’t have a political voice. My grandfather used to say, “You know, we’re going to all be sent to camp.” And my mother said, “Oh no. You might be, but I’m a citizen.” And he said, “Yeah well, you’ll see.” And she said later when, of course, everybody was rounded up and sent to the camps, he said, “See?”

Katayama: When the looming threat of incarceration became a reality, it caused significant disruption in people’s lives. Jean talks about the impact it had on her family.

Hibino: So my mom always tells the story about selling everything they own to the junkman—was it thirty-five bucks or something? Refrigerator, stove, furnishings, store goods, everything was sold. They knew that there was going to be a short amount of time where things had to be done. Businesses, affairs had to be put in order, including the dog, which was so sad! Oh my God, their poor dog, they had to get—ah—get rid of. And I think there was an actual story where the dog came back after they gave it to the junkman, that the dog wandered back home, and we’re all crying when we heard that story.

Katayama: People had a matter of days to pack up their things and organize their lives before reporting to assembly centers. They could only take what they could carry. And they had to make some pretty heart-wrenching decisions about what to take and what to leave behind. Here’s Nancy again, sharing her mother’s memories of those uncertain days.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades in. Sound of door opening.

Ukai: When they were all packing to go, she said my grandfather packed up this box very carefully, and she thought it was, oh, treats or tools, she didn’t know. And she said when they got to camp, they opened it up and it was filled with eucalyptus leaves. And she said, “You fool, why did you waste this precious space on this?” He told her, “I thought we may never go back to Berkeley,” and he loved the fragrance of the Eucalyptus leaves, and they reminded him of the Berkeley that he loved. And so she said, “I wished I had directed my anger at the US government and not my father…who didn’t know if he’d ever go back to this place that he loved so much.”

Soundbed: sound of door closing.Instrumental music fades out.

Katayama: Bruce Embrey, a Sansei whose mother was incarcerated in Manzanar in California, heard stories about the sale of his family’s store in the Los Angeles area.

Bruce Embrey: I have the receipt, actually, for the sale of the store, and they kept it. They sold it for half of what they paid for it. They got about 50 percent. What was remarkable to me was that there was very little resentment about it. You know, you lose an asset to somebody, you, you generally are kind of upset, right? I mean, I, I know everybody says, “Oh, it’s amazing how they’re not bitter.” Yeah well, close the door and get into a family discussion and see how bitter people really are.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades in.

Katayama: Life in Manzanar and Topaz was a difficult adjustment for many. To this day, descendants of the camps have visceral memories of the stories their families told about what it was like to be incarcerated in the desert, far from the lives they once knew. Here’s Bruce Embrey again sharing his grandmother’s first impressions of Manzanar.

Embrey: My grandmother was convinced that this was a desolate area, I mean, it was bulldozed, there was nothing around but barracks. And that while you had these majestic mountains in the back, apple orchard—this is, you know, the quote she said, “It’s a place like this. They brought us to a place like this: beautiful on the one hand, desolate on the other.” And she was convinced they were brought there to be shot. She thought they were being removed to a far-flung area, meaning far from a large metropolitan area like Los Angeles, essentially to be either worked to death or, or, or killed. That was her framework. And so she cried every day until she finally got it together, and came back and said, “No, we’ve got to survive this crap.”

Katayama: For many of the incarcerated Issei and Nisei, survival in camp meant trying to create some semblance of a normal life. They built schools, grew gardens, and honed crafts like woodworking and photography. Susan Kitazawa, a Sansei, recalls that her grandfather did this while incarcerated at Manzanar.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades out.

Kitazawa: It’s like my grandfather, who had a nursery, being able to be in charge of the victory garden. It was like, Oh, I get to use my best skills, even though I’m locked up.

Katayama: Ruth Sasaki, a Sansei whose parents were incarcerated at Topaz, remembers learning about her mother’s role in creating an education system while in camp.

Ruth Sasaki: They called a meeting of all the college graduates, you know, among the internees and organized preschools for the kids. And so my mom was teaching preschool in Tanforan. And then when they were transferred to Topaz, they did the same thing. They organized a preschool system. So from ’43 to ’45, she was the supervisor of Topaz preschools.

Katayama: Alan Miyatake, a Sansei, heard many stories about his grandfather, Toyo Miyatake. Many people know Toyo today as the official camp photographer of Manzanar. But he didn’t start out that way. Toyo originally smuggled a camera into camp with him. In fact, Alan’s father remembers when Toyo first showed him the camera.

Alan Miyatake: The way my father told the story was that one day in camp, he took him aside and opened up his suitcase and said, “Look what I have.”

Soundbed: instrumental music fades in.

Miyatake: It terrified my father, because, you know, he thought, Wait a minute, I know that’s not legal. So he explained it to my dad that, you know, “I’m going to make a camera and I’m going to photograph this injustice, in hoping that it would never happen again.”And he started, you know, making a camera. So he mounted a lens onto a drainpipe, onto the male part of the drainpipe, and then the female end of the drainpipe was mounted to the box. So that was the focusing device that made the camera operate.

Katayama: But Toyo’s photography didn’t go completely unnoticed by the camp administration in Manzanar.

Miyatake: As the story goes within our family, that in order to kind of cover himself, Ralph Merritt, the director, he made up this rule. Once he said, “Yeah, go ahead and take pictures, but you can’t snap the shutter.” And I’m, I’m guessing that if he ever got caught, you know, and if it went to higher authorities, at least Ralph Merritt could say, “Well, he wasn’t the one that snapped the shutter.”

Katayama: Eventually, Ralph Merritt gave Toyo permission to take photographs as the official camp photographer, as long as he had supervision. It was a camp rule that he needed to be accompanied by someone who was not Japanese American, like the wife of a camp worker, when he would take photographs there. This underscored his lack of autonomy, both as a professional photographer and a prisoner with restricted freedoms.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades out.

Katayama: Despite the fact that many Japanese Americans were able to create lives for themselves inside the prison camps, the indignities of incarceration were never far from their minds. Even Japanese American service members fighting on behalf of the United States and democracy abroad had families who were incarcerated at home. Here’s Rev. Michael Yoshii, a Sansei whose family was incarcerated at Topaz.

Michael Yoshii: My father’s brother, he was already part of the military when the war broke out. And then he got assigned to the 442nd in the process of it.

Katayama: That’s the 442nd Infantry Regiment of the United States Army. The 442nd is the most decorated regiment in US military history. Its daring feats, like the rescue of the “Lost Battalion” in Italy, have made the 442nd the stuff of legend. But this unit was also segregated within the US military.

Yoshii: My father and his parents went to Tanforan initially. His brother was wounded in the war in Europe and had his arm, uh, blown off. And he kind of had to go to a hospital and then do some recovery. He had a prosthetic arm put on. That was like a lifelong injury from the war. You know, my grandparents were really upset about that. I think he was able to come back and visit them in Topaz on one of his return trips.

Katayama: And it wasn’t just the indignities of losing livelihoods, property, and their freedom that haunted Japanese Americans incarcerated in these camps. There was also the constant threat of harm and death. Here’s Masako Takahashi, a Sansei born in Topaz, reflecting on this tension.

Masako Takahashi: My family and all those other people lived under the constant threat of murder. I mean, whatever baseball games or arts and crafts they were practicing, there were armed guards pointing guns at them at all times.

Katayama: And she means this literally. All the prison camps featured tall guard towers with armed guards and searchlights. The guard towers stuck out in otherwise isolated landscapes.

M. Takahashi: So no wonder they were tense.

Katayama: This tension permeated Manzanar, too. In December 1942, internal political divisions with the camp’s federal administrators, and within the Japanese American community, culminated in a violent uprising at Manzanar. Hans Goto, a Sansei whose father was a doctor and working in Manzanar’s hospital, remembers hearing about this.

Hans Goto: There was a riot in the camp. I think approximately 2,000 people came out for this riot. They were shouting, they were chanting, they were very angry. The details aren’t really clear. But suddenly the military police opened fire, which they weren’t supposed to do.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades in.

Goto: So two people were instantly killed and nine people were wounded, and that sort of dispersed the crowd. They brought the people into the infirmary, where my father was, and the whole staff was, was on duty at that time.The people who were killed and the people who rioted, were they shot from the front, or were they shot from the side and back? And the controversy was: if they were shot from the front, that means they were charging the guards. And if they’re shot from the side and back, that meant they weren’t charging the guards. The military held an inquiry within a few days of the actual event. They highly encouraged my dad, according to him, to report that they were all shot from the front. Because he was also the physician coroner. He said, “No, I’m not going to do that.” And they said, “Well, you have to do this.” And he goes, “Uh, no, they, they were shot from the side.”

Soundbed: instrumental music fades out.

Katayama: The Manzanar Uprising had far-reaching consequences. Within two months, the US government required all incarcerees at all ten federal prison camps to complete a “loyalty questionnaire.” This questionnaire was administered in part to identify and remove so-called “troublemakers” from the camps. Beyond the irony of a loyalty survey for people unjustly imprisoned by their own government, the questionnaire language was confusing and led to further problems. For example, Question 27 asked Nisei incarcerees if they would be willing to serve on combat duty wherever they were assigned. Question 28 asked individuals if they would swear unqualified allegiance to the US and forswear any form of allegiance to the Emperor of Japan. Many incarcerees answered “no” and “no” to those two questions. And as a result, they were labeled “no-no boys” and ultimately confined at the high security Tule Lake Segregation Center, deep into rugged Northern California. The Manzanar Uprising also had consequences for Dr. Goto.

Goto: The next day he was relieved of all his duties. He was the head physician.

Katayama: After refusing to sign the death records of the young Japanese Americans who were shot and killed at Manzanar, Dr. Goto and his family were sent to Topaz. But they also witnessed deadly violence in the Utah desert.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades in.

Ukai: Wakasa was murdered on April 11, 1943, at 7:30 at night. He was shot through the heart. He fell on his knees. He fell on his back. He died instantly. The bullet went through his heart and also pierced his spine.

Katayama: James Hatsuaki Wakasa, a 63-year-old Issei man, was days away from leaving Topaz for another camp, when he was killed by a camp sentry. He was shot from a guard tower, 300 yards away. The military took his body and then spun a false narrative about Wakasa’s death. Masako Takahashi recalls Wakasa’s tragic murder.

M. Takahashi: He was four days away—he already had a pass to leave camp, four days away. And of course he wasn’t trying to flee. That adds to the sorrow.

Katayama: The story of James Wakasa’s murder has been told many times over the years by survivors and descendants of Topaz. Everyone knew about it. Everyone had some kind of connection to it.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades out.

Katayama: But not everyone tells the same version of the tragedy. Patrick Hayashi, a Nisei who was born at Topaz, and Nancy Ukai, remember hearing this story many times as children. This incident profoundly shaped their families’ incarceration experiences.

Ukai: That is just burned into my childhood memory.

Patrick Hayashi: My mom told me an old deaf man, Mr. Wakasa, was walking his adopted, stray dog around the perimeter of the camp—and he would do that every afternoon. His dog got caught in the barbed wire fence, and Mr. Wakasa went to save him and release him.

Ukai: And I just remember to this day my mother’s emotion and anger, and saying, “They didn’t have to kill him. He was deaf.” Well, he wasn’t deaf. That was one of the rumors, which I think the government probably created to, you know, rationalize his murder.

Hayashi: The sentry ordered him to back away from the fence, but because he was deaf, he couldn’t do it, and so the sentry shot and killed him.

Ukai: He was accused of escaping through the fence, and it was in the national papers, and that never got corrected.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades in.

Katayama: Remember Dr. Goto, Hans’s Father? When he and his family were sent to Topaz after the uprising at Manzanar, he became the physician and coroner at Topaz. In a twist of fate, it was Dr. Goto who signed the death certificate for James Wakasa.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades out.

Newsreel from the 1940s with instrumental music: “America waited out World War II’s last tense hours. At the White House, President Truman, State Secretary Byrnes, and Cordell Hull stood by for the momentous surrender message from the Japanese. Radiomen, sound and camera crews, and worldwide newsreels kept vigil with Washington reporters. Then, after tantalizing hours of rumors and guesses, came the President’s historic announcement, August 14, 1945.”

Katayama: After several years of incarceration, on December 18, 1944, Americans learned that the US government approved the closure of all the camps by the end of 1945. However, the last camp didn’t actually shutter until March 1946—nine months after the war against Japan in Asia ended. This sudden change left Japanese Americans struggling to plan for the future. Remember, many of them had either sold or lost their homes and businesses before being forcibly removed from their communities, so they didn’t have much to return to.

Mitchell Higa: A big part of it was my dad’s parents’ business taken away when they went to camp, and then coming out of camp penniless. And then having to go through the humiliation of going on government assistance, coming out of camp broke. No prospects, no money, no father.

Kitazawa: My father’s parents were, um, working their very, very small family flower nursery in San José at the time. And my father told us that for his father, even though he wasn’t happy about being taken away from his home and his nursery, that he was able to sell the family nursery and business to people at the Quaker Meeting House in San José, where he was a weekend custodian.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades in.

Kitazawa: So they bought the place on paper for a dollar and they held it for them until they came back home again, which was really fortunate that they had that connection to people in the white community, and didn’t lose their land or have to sell it super cheap.

Katayama: That was Mitchell Higa, a Sansei whose family was incarcerated at Manzanar, and Susan Kitazawa. Here’s Alan Miyatake again.

Miyatake: I always pictured that they just came back to Boyle Heights and moved into their house. But later on, I found out that because of a, a lease that was set up, that Bobby, my uncle, told me, “Oh no, no, we, we had to live across the street for a while, because there were still people living in our house.”

Katayama: But not everyone was able to return to their homes and communities. Some felt pressured to stay away from the West Coast, and others saw opportunities to begin anew in other parts of the United States. Here’s Ron Kuramoto, a Sansei whose mother was incarcerated at Manzanar.

Ron Kuramoto: What they were given when they were released was a bus ticket and $25 in cash per person.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades out.

Kuramoto: Those were the federal guidelines for releasing prisoners from, [laughs] you know, from federal prison, was to give them a bus ticket and $25 to wherever they went. They said, “So, many of the people, they were glad to be released, but they had nowhere to go.” Interestingly enough, that’s what led to a lot of the diaspora of Japanese Americans.

Hibino: So we [laughs] ended up in this extremely small, white town in Connecticut, and I always thought I was white until I was about ten. When you left the camp, the War Relocation Authority had put out pamphlets that said to the Japanese, “It is advisable that you move as far away from California as you can. Stay away from other Japanese. Try to become even more American than, than [laughs] you think you are, than you already are.” They were just trying to say, “Try to assimilate, be white, and don’t rock the boat. Don’t make waves. Don’t stick out. Just quietly go about your business, even though this horribly unconstitutional thing has just happened to you and you’ve suffered all this trauma.” I think that is part of the reason why only half of the Japanese moved back to the West Coast after the war.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades in.

Hibino: My dad really took that to heart. And so he always told us he chose to never go back to California because of the racism and the horrible experiences his family suffered. And so we’re going to go up here, and we’re going to try to live the American dream and not so much talk about what happened to us in 1942.

Katayama: That was Jean Hibino again. Some Japanese American students were able to leave camp during the war to attend college in the Midwest or on the East Coast. Carolyn Iyoya Irving, a Sansei whose family was incarcerated at Topaz, recounts her mother’s experience moving to New York State during the war while her parents remained in camp.

Carolyn Iyoya Irving: The Quakers, the American Friends Service Committee, really made a concerted effort to help kids in camp to go to college. And so I think they helped with the brokering of the government paperwork to find out which colleges would accept Japanese Americans from the camps. And so I think, by and large, most of them were East, because you were away from the West Coast. She ended up leaving for Vassar in, um, August of 1943 by herself, you know, on a train, saying goodbye to her parents behind barbed wire and heading out to Poughkeepsie.

Katayama: Moving away from their homes and centers of Japanese American culture led some to become isolated from the community. These moves have had a profound impact on intergenerational identity and belonging. Both survivors of incarceration and their descendants have had to live with the consequences of lives uprooted, torn apart during and after World War II. Here’s Masako Takahashi again.

M. Takahashi: My parents were super American. When I was young, they took my brother and me to Washington, D.C., to see the Lincoln Memorial; we went to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to see the Liberty Bell; we went to Manhattan, New York City, to see the Statue of Liberty. These were like really iconic American institutions and parts of history. Those touchstones, they wanted to go see them for themselves, because that’s how they felt through the war and continued after the war. My Uncle Will went in the 442nd. These people wanted to prove their Americanness, even die for America.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades out.

Katayama: Here’s Kimi Maru, a Sansei, whose family was incarcerated at Topaz.

Kimi Maru: You know, even my kids had friends growing up—they’re Yonsei, fourth generation—who didn’t know how to use chopsticks, because their families didn’t eat Japanese or Asian food. [laughs] And largely, I think that’s because of the camps, because they didn’t want to really relate to being Japanese. They wanted to prove their Americanness, how they thought about themselves, you know, and what it meant to be American, but not really understanding what it meant to be Japanese American.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades in.

Hayashi: I think trauma can be transmitted nonverbally. And because the silence among Japanese Americans, among everyone, is textured, different types of silence mean different things and convey different emotions, and I think that’s how I learned about the emotional tone of the camps and the devastation it had.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades out.

Vox pop:

Matsumura: My dad doesn’t talk about camp life, he’s very quiet about it.

M. Takahashi: Just generally speaking, it was horrible and shocking, but they, like many others, did not speak that much about camp experience.

Hayashi: I’m typical of third-generation Japanese Americans. We grew up hearing next to nothing about the camps.

Margret Mukai: You know, we were Japanese Americans. We were supposed to be quiet.

Sasaki: She didn’t talk that much about the war or those experiences.

Jennifer Mariko Neuwalder: “The nail that sticks up gets hammered down.”

Katayama: Incarceration was an agonizing experience for most Japanese Americans. It was difficult for many to talk about. The silence was about shame, it was about trauma, and it was about cultural influences that encouraged people not to dwell on the past. This meant that children of survivors rarely learned about incarceration firsthand. Here’s Lori Matsumura, a Sansei descendant of Manzanar.

Lori Matsumura: My dad was so quiet, and so he didn’t discuss camp life unless we asked him or hounded him, he didn’t discuss it, which is unfortunate, because he’s gone now. Now I have so many questions I wish I would have brought up. Almost everyone’s gone now.

Katayama: Masako Takahashi remembers growing up with shame about incarceration.

M. Takahashi: As a child, I felt ashamed, because it seemed bad to be the children of people who the government wanted to lock up and called an enemy. I wasn’t proud to be Japanese or proud to have been born in a concentration camp or, you know—so I guess they were just trying to spare us feeling bad, so they just didn’t talk about it and looked forward.

Katayama: Peggy Takahashi is a Sansei whose parents were incarcerated at Manzanar.

Peggy Takahashi: There’s a whole generation of Japanese people, probably my age and a little younger, whose parents made a conscious decision not to make the Japanese culture prominent in their lives, um, because of what happened during the war.

Katayama: Peggy talks about how many people never learned about Japanese American culture or the history of incarceration in school.

P. Takahashi: It wasn’t talked about at all. In our US history books in the 1970s, there was one—literally one paragraph—about the incarceration. Literally one paragraph.

Goto: No. Not at all. Never heard about it. What’s ironic is—just, just for a little tidbit—is that one of my high school history teachers was a little kid in one of the camps. And he never mentioned it, ever, in history. And he taught US history. It was just a sign of the times.

Katayama: That was Hans Goto again. Here’s Miko Charbonneau, a Yonsei whose family was incarcerated at Manzanar.

Miko Charbonneau: Sometime in middle school, we were learning about the Holocaust, and our teacher, he was telling the whole class like, “Well, Jewish people were put in camps.”

Soundbed: instrumental music fades in.

Charbonneau: And I was like, Wait, my grandmother was put in a camp. So I raised my hand and said, “My, my grandparents were put in a camp, but they were put in camp by America.” And there was like this awkward silence, because all the kids were confused and had never heard about it, and he clearly did not know what to say. And after this silence, all he said was, “Well, we didn’t kill people.” And so I really remember that, and it’s sort of maybe the first time I feel like my experience was disparaged or, or put down.

Katayama: If descendants learned about this history at all in school, it was often brushed off as something insignificant. Some teachers outright denied Japanese American incarceration ever happened. Here’s Susan Kitazawa.

Kitazawa: One time when I was in elementary school, we had to talk about our families or how our parents met, and so I said, “My parents met when they were locked up in the prison camp.” And the teacher got really mad at me and said, “You’re supposed to tell the truth. Don’t make things up.” And I said, “That really happened. And my parents told me that.” And the teacher said, “Nothing like that ever happened in the United States.” And she got really angry at me. And I felt really bad, because she thought not only that I was lying, but that my parents were lying to me. And so my mother said I could take the book to school and show her the book. And I showed her the book and she just brushed it off like, “Yeah, whatever. Things like that don’t happen in America.” And so from that experience, I learned to just kind of shut up about it.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades out.

Katayama: This pushback reinforced silence within the community. The language used to describe what happened to Japanese Americans during World War II is equally important in acknowledging this past. It impacts how people remember events, and even how they continue to teach this history in school. It’s become a sensitive topic for many descendants of incarceration.

Here’s Jennifer Mariko Neuwalder, a Sansei whose family was incarcerated at Topaz, and Ron Kuramoto again.

Neuwalder: Yeah, I mean, I certainly grew up with “relocation,” not even “forced relocation,” “relocation” and “internment camps.”

Kuramoto: There would be references that we could overhear about somebody they knew from “camp.” And that was kind of the euphemistic talk about that.

Neuwalder: And of course, as a little kid I was like, “Camp,” summer camp! You know, like [laughs] it was confusing, um, because it was a camp, but you couldn’t leave. And it was a camp in the middle of the desert with your whole family and all these other families.

Kuramoto: And as kids, we thought this was maybe something like summer camp. And we thought, Wow, this is really cool, everybody went to the same summer camp. But they were there for four years, so [laughs] it was a long summer camp.

Katayama: But it was far from a summer camp. People have referred to the camps by different names over the years. Even the US government has changed its terminology. Here’s Hanako Wakatsuki-Chong, a Gosei descendant of Manzanar and National Park Service Superintendent of the Hono’uli’uli National Historic Site, discussing this.

Hanako Wakatsuki-Chong: And the US government, you know, also used “concentration camp” during World War II, and eventually the terminology kind of transitioned.

M. Takahashi: It was first called a “concentration camp.” Later, after the discovery of Auschwitz and Dachau and so on, the words “concentration camp” had meanings that the government preferred not to be associated with, so they started calling it “internment camps” and “relocation.”

Katayama: That was Masako Takahashi again. The euphemistic language about incarceration that Ron referred to has long weighed on the minds of survivors and their descendants. Densho is a nonprofit organization founded in 1996, whose mission is to preserve and share history of the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans in order to promote equity and justice today.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades in.

Katayama: In its guide to terminology, Densho explains that “internment” refers to “the legally permissible, though morally questionable, detention of, quote, ‘enemy aliens’ in time of war.” In other words, Issei immigrants. Therefore, this terminology glosses over the fact that the federal government actually incarcerated American citizens of Japanese ancestry—Nisei children and young adults—without due process. More recently, in 2022, the Associated Press changed its style guide to embrace this distinction. This is why we’ve been using the word “incarceration” throughout this series. But others have advocated for even more changes in terminology. Here’s interviewer Roger Eardley-Pryor asking Masako Takahashi about her birth. You can hear how integral terminology is to her and her family’s incarceration experience.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades out.

Roger Eardley-Pryor: Can you tell me the date of your birth and the location, please?

M. Takahashi: January 29, 1944, in Topaz Concentration Camp in Utah. My mother said it was a concentration camp.

Katayama: Here’s Jennifer Mariko Neuwalder again.

Neuwalder: Linguistically they were concentration camps. They were places where people were concentrated, because of some ethnic cultural characteristics that were deemed to be abhorrent, and they were locked up as families. Um, I know there’s a lot of controversy, but I think, you know, there are lots of concentration camps around the world. To my mind, it’s about the removal of human rights and liberties of movement, and the literal concentration and segregation of one cultural group against their will.

Katayama: Jennifer is speaking about this from the perspective of her two identities. She is a descendant of a Japanese American mother incarcerated at Topaz, and of a family of ethnically German Jews who survived the Holocaust.

Neuwalder: I think the term “concentration camp” has acquired very specific meanings to specific people. Um, but you know, maybe it will be reclaimed by the Japanese American community over time.

Katayama: But not everyone agrees.

Kuramoto: I don’t really hear many people refer to the incarceration camps, which is now the preferred terminology, as “concentration camps” anymore, other than maybe to describe some of the things that went on that are similar to that. But, uh, no, they were not mass extermination type of facilities, such as in the European experience.

Katayama: That was Ron Kuramoto again. Indeed, language—and reclaiming language—is an important discussion, particularly in the Japanese American community. Here’s Patrick Hayashi again, recalling the conversations he had about this with Topaz survivors during a meeting with the Class of ’45. It’s a group of Japanese American students who attended high school behind barbed wire.

Hayashi: The question was: what do you call Topaz? Some people wanted to call it a “concentration camp.” Everyone was in agreement that “internment camp” was just not proper, but you could call it a “confinement site,” something like that. They asked me what I thought, but I didn’t say anything. I thought it was up to them.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades in.

Hayashi: In the end, they decided to call it a “concentration camp.” And I could see a complete transformation occur once they settled that issue. They became proud of their lives and proud at how they conducted themselves in the camps.

Katayama: Clearly, language matters. It’s not just words, it’s also about agency. Since the end of World War II, Japanese Americans have worked to reclaim the narrative of their incarceration experiences. This reclamation includes not only pushing for acknowledgment of this past, but also intergenerational conversations about the nuance of language and its implications. Without a doubt, each generation of descendants will need to begin this process for themselves.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades out.

Katayama: Thanks for listening to “‘From Generation to Generation’: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration” and The Berkeley Remix. Join us next time for more on identity and belonging in the Japanese American community.

Theme song fades in.

Katayama: This episode features interviews from the Oral History Center’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, and includes clips from: Miko Charbonneau, Bruce Embrey, Hans Goto, Patrick Hayashi, Jean Hibino, Mitchell Higa, Carolyn Iyoya Irving, Susan Kitazawa, Ron Kuramoto, Kimi Maru, Lori Matsumura, Alan Miyatake, Jennifer Mariko Neuwalder, Ruth Sasaki, Masako Takahashi, Peggy Takahashi, Nancy Ukai, and Rev. Michael Yoshii. Music from Blue Dot Sessions. Additional archival audio from the US Office of War Information and the Internet Archive. This episode was produced by Rose Khor, Roger Eardley-Pryor, Shanna Farrell, and Amanda Tewes. Thank you to the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant for funding this project. To learn more about these interviews, visit the Oral History Center’s website listed in the show notes. I’m your host, Devin Katayama. Thanks for listening, and I will talk to you next time!

Theme song fades out.

END OF EPISODE

The Berkeley Remix Season 8, Episode 3: “‘Between Worlds’: Japanese American Identity and Belonging”

In this episode, we explore identity and belonging in the Japanese American community.

For many Japanese Americans, identity is not only personal, it’s a reclamation of a community that was damaged during World War II. The scars of the past have left many descendants of incarceration feeling like they don’t wholly belong in one world. Descendants have navigated identity and belonging by participating in Japanese American community events and supporting community spaces, traveling to Japan to connect with their heritage, as well as cooking and sharing Japanese food. However, embracing Japanese and Japanese American culture can highlight for descendants their mixed identities, leaving them feeling even more like they have a foot in multiple worlds.

In season 8 of The Berkeley Remix, a podcast of the Oral History Center at UC Berkeley, we are highlighting interviews from the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project. The OHC team interviewed twenty-three survivors and descendants of two World War II-era sites of incarceration: Manzanar in California and Topaz in Utah. This four-part series includes clips from these interviews, which were recorded remotely via Zoom. Using healing as a throughline, these life history interviews explore identity, community, creative expression, and the stories family members passed down about how incarceration shaped their lives.

This season features interview clips from the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project. This episode includes clips from: Miko Charbonneau, Hans Goto, Jean Hibino, Roy Hirabayashi, Carolyn Iyoya Irving, Susan Kitazawa, Kimi Maru, Lori Matsumura, Alan Miyatake, Jennifer Mariko Neuwalder, Ruth Sasaki, Steven Shigeto Sindlinger, Masako Takahashi, Peggy Takahashi, Nancy Ukai, Hanako Wakatsuki-Chong, and Rev. Michael Yoshii. To learn more about these interviews, visit the Oral History Center’s website.

Produced by Rose Khor, Roger Eardley-Pryor, Shanna Farrell, and Amanda Tewes. Narration by Devin Katayama. Original theme music by Paul Burnett. Additional music from Blue Dot Sessions. Album artwork by Emily Ehlen. A special thanks to the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant for funding this project.

The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government.

LISTEN TO EPISODE 3 ON SOUNDCLOUD

PODCAST TRANSCRIPT: “‘Between Worlds’: Japanese American Identity and Belonging”

Soundbed: instrumental music fades in.

Ruth Sasaki: In some respects, I guess my whole life I felt sort of a duality, like I have one foot in two different worlds: Japan and America. I didn’t know who I was, and it felt like I couldn’t speak up for myself. When I understood that my values that I had been raised with were majority culture values in Japan and were valued, it just changes the whole way you feel about yourself.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades out. Theme music fades in.

Devin Katayama: Welcome to The Berkeley Remix, a podcast from the Oral History Center at the University of California, Berkeley. The Center was founded in 1953, and records and preserves the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world. You’re listening to our eighth season, “‘From Generation to Generation’: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration.” I’m your host, Devin Katayama.

This season on The Berkeley Remix, we’re highlighting interviews from the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project. The OHC team interviewed twenty-three survivors and descendants of World War II-era sites of incarceration at Manzanar in California and Topaz in Utah. In this four-part series, you’ll hear clips from these interviews, which were recorded remotely via Zoom. These life history interviews explore identity, community, creative expression, and stories family members passed down about how incarceration shaped their lives.

As a heads up, generational names for Japanese Americans are going to be important in this series. Issei refers to the first generation of Japanese immigrants to the United States. Nisei are the second generation, Sansei the third, Yonsei the fourth, and Gosei the fifth. Just think about counting to five in Japanese: ichi, ni, san, shi, go.

This is episode 3, “‘Between Worlds’: Japanese American Identity and Belonging.”

Theme music fades out.

Katayama: What does it feel like to have a foot in multiple worlds? How does this affect the search for personal identity? For many Japanese Americans, identity is not just personal, it’s a reclamation of a community that was damaged during World War II. The scars of the past have left many descendants of incarceration feeling like they don’t wholly belong in one world.

Miko Charbonneau: I think that I’ve always felt like stuck between worlds and never really belonging to any place entirely.

Katayama: That was Miko Charbonneau, a Yonsei. Here’s Hanako Wakatsuki-Chong, a Gosei, talking about the role that incarceration plays in her search for identity. Both women’s families were incarcerated at Manzanar, and they have multiple ethnic heritages.

Hanako Wakatsuki-Chong: The biggest thing that I feel is the loss of identity. Because it’s like I’m still trying to find my identity, [laughs] um, and it’s because I feel like you couldn’t be proud of your heritage during camp, and afterwards it was basically like Americanization.

Katayama: Here’s Susan Kitazawa, a Sansei and descendant of Manzanar.

Susan Kitazawa: And then also when I was in later elementary school, we were the only family in our town who wasn’t a white family. Church, Girl Scouts, unless it was a multi-age thing and my sister happened to be in the group with me, I was always the only person of color.

Katayama: Many other Japanese Americans can relate to Susan’s experience. Steven Shigeto Sindlinger is a Yonsei whose birth mother was incarcerated at Topaz. He grew up in Michigan with his adoptive mother, who was from Japan, and his white, American father.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades in.

Steven Shigeto Sindlinger: There just weren’t any other individuals of Asian descent. There were only a couple, and none that we knew. So it was a little, I don’t want to say disappointing, that there weren’t more Japanese or Asian representation in the school system.

Katayama: Jennifer Mariko Neuwalder, a Sansei whose mother’s family was incarcerated at Topaz, had a similar experience as Susan and Steven. Additionally, her father was Jewish and his family survived the Holocaust.

Jennifer Mariko Neuwalder: My parents integrated the town’s country club single-handedly. First mixed couple, first Asian, first Jewish. I had no awareness of that, except one time when I was probably eight or nine years old, this very blonde woman passing by me said, “You’re so dark you could be a little Black child.” And there were no African Americans in this club. At the time it was like very, very white. Um, and it stuck with me. At the time I thought it was like a great compliment, I was like, Yeah! But over the years, I was like, That was not meant to be a compliment. [laughs]

Katayama: Feeling like an outsider can take many forms. For some, it manifests in something as intrinsic as a name. Names are not just words, they carry a lot of meaning.

Michael Yoshii: My name is Michael Arthur Yoshii. A lot of my friends had Japanese middle names. Uh, my parents kind of didn’t give us Japanese middle names on purpose, and I think that was to not make us stand out and not draw attention to being Japanese, per se. I think that kind of was the explanation.

Katayama: Rev. Michael Yoshii is a Sansei whose family was incarcerated at Topaz. Another way Japanese Americans can feel like outsiders is through language—or not learning to speak Japanese at all.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades out.

Katayama: After World War II, many survivors of incarceration didn’t teach their children how to speak Japanese. Here’s Lori Matsumura, a Sansei descendant of Manzanar.

Lori Matsumura: I know that the Issei—my grandmother’s generation, Issei—did she not want the Nisei, which is my dad’s generation, to speak Japanese because of being sent to Manzanar and having to show that you are an American? Is that why they didn’t speak Japanese at home? I’ve always wondered that, but I never did find out the reason why.

M. Takahashi: We only spoke English at home. I’m sorry I don’t speak Japanese. I’ve learned that a language is not just a dictionary, it’s a way of thinking, it’s a cultural reality.

Katayama: That was Masako Takahashi, a Sansei and a child survivor of Topaz. Here’s Hanako again.

Wakatsuki-Chong: I remember my dad used to joke, saying he knows enough Japanese to read a menu, you know, and that’s about it.

Katayama: Nancy Ukai, a Sansei descendant of Topaz, wasn’t able to speak to her grandparents when she was a child.

Nancy Ukai: When I was in elementary school, because I didn’t speak Japanese, and they didn’t really speak English, we didn’t communicate, and there would always be these [laughs] older people sitting on the sofa, or, you know, as a kid you just couldn’t joke with them, talk with them.

Katayama: When you can’t speak with your elders, it’s hard for them to pass down stories from generation to generation. Family stories can help you understand who you are or where you come from. When you lose this ability to communicate, it’s hard to recover. You might feel like you have a foot in multiple worlds.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades in.

Katayama: As a result of World War II incarceration, Japanese Americans had their lives uprooted and saw their community centers dissolved. Ruth Sasaki is a Sansei whose family was incarcerated at Topaz. Her family lived in San Francisco’s Japantown prior to forced removal. There were about 5,000 Japanese Americans living in the area, which was about 6 city blocks, with around 200 Japanese- and Japanese American-owned businesses. When Ruth’s family returned to San Francisco, they saw that Japantown had disintegrated.

Ruth Sasaki: The others remember Japantown and they remember living in a situation where they were surrounded by the Japanese community. Because we moved out of Japantown to the Richmond District when I was so little, I’ve always felt sort of like I missed out on something, you know?

Katayama: After this fracturing of community, having a place to gather became sacred for survivors and their families. Many wanted to reclaim a space for themselves. They made an effort to form new cultural centers where they could come together as a Japanese American community. Not only were these centers meaningful places to convene, but they also became places where younger generations could learn about their heritage.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades out.

Matsumura: Nikkei Kai was a Japanese community center. And it started postwar in my grandmother’s house, because they wanted a meeting place where they can get together and talk about things and learn from each other, like a support community for themselves, for the Japanese and Japanese Americans.

Katayama: That was Lori Matsumura. Here’s Rev. Michael Yoshii again.

Yoshii: A big portion of time was spent in that Japanese American community, an invisible community, is the way I would call it.

Katayama: These community spaces weren’t just informal and invisible—they were physical places, too. One of the places where people came together was at church. Here’s Hans Goto, a Sansei whose family was incarcerated at both Manzanar and Topaz, talking about growing up in Watsonville, California, where he had ties to two different churches.

Hans Goto: The Japanese American community was actually split into two groups based on religion.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades in.

Goto: And my mother, because her mother, uh, was either a Methodist or Presbyterian, went with the Christian church. We were associated with them, even though a lot of my friends were Buddhist. And so we crossed the lines a lot, you know, we got together a lot. But that was the social as well as religious thing. There was a lot of interchange between the two. And that was where the culture was.

Katayama: But this split between churches wasn’t always as seamless as Hans’s experience. It also sometimes reflected larger religious and cultural divides within the Japanese American community. Carolyn Iyoya Irving is a Sansei descendant of Topaz.

Carolyn Iyoya Irving: One thing that always stuck out in my head as a kid is remembering the differentiation between the Christian Japanese Americans and the Buddhists. So for instance, we were sort of told we couldn’t dance in the Obon Festival, which is the big Buddhist festival in August. And I just remember my dad saying, “Yeah, it just really doesn’t look good if the daughters of the, you know, Presbyterian minister are off dancing in Obon.”

Soundbed: instrumental music fades out.

Irving: And so there was this kind of artificial division, in a way, between the Christian churches and the Buddhist churches. Not that we couldn’t be friends or go to the Obon Festivals, but there were two distinct communities, I think, of Japanese Americans.

Katayama: Japanese American children didn’t just go to church to worship. Church also served as a community space where they could attend Japanese language school. Roy Hirabayashi, a Nisei whose family was incarcerated at Topaz, attended language school at his local church, upon the urging of his mother.

Roy Hirabayashi: She felt it was important for us to learn Japanese, so she required that we go to language school on Saturdays. It ended up also where we were going to this one Japanese community center; after the language school, they would have church services.

Katayama: In addition to language school, some churches hosted special events. These events provided space for the community to gather and celebrate their Japanese American heritage. Here’s Rev. Michael Yoshii talking about his church’s spring bazaar.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades in.

Yoshii: We had something called the Spring Festival Bazaar. It’s like a festival event where the whole community comes together to work on a particular thing together. It was a coming together of community after the war. They started it in the late fifties.

Katayama: Japanese American churchgoers had a tradition of going to each other’s bazaars.

Yoshii: They were supporting each other economically and financially by having that kind of network of, of support with one another, as well as the larger community that would come to particular events. I think there was this other element of it where we were revisiting our Japanese American history, our identity.

Katayama: Another celebration that brings the community together is Nisei Week. This is an annual festival in the Little Tokyo neighborhood of Los Angeles. Kimi Maru, a Sansei whose family was incarcerated at Topaz, enjoys participating in this event.

Kimi Maru: It’s a tradition that’s been going on like every summer in early August, and it’s two weekends in a row. There’s a Nisei Week parade, where all these different community groups, as well as different schools, dance schools, they do this parade through Little Tokyo.

Katayama: Even though there are many opportunities to connect with the Japanese American community, not everyone has always felt welcome. Here’s Susan Kitazawa again.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades out.

Kitazawa: My initial experience of my attempts to enter the Japanese American community in San Francisco were horribly painful and disappointing.

Katayama: Susan had a hard time finding community when she was in her mid-twenties.

Kitazawa: I had heard about this organization and I had heard that they wanted volunteers. And so when I first moved to San Francisco, I went over there one day, called ahead and made an appointment. And at the entrance I remember there were two women and a man, and they were sort of about my age. I said, “Oh, I’m here to talk with you about volunteering.” And he said, “Who are you? I’ve never seen you at any community events.” And I said, “Well, no, because I just moved out here. I grew up on the East Coast.” He said, “Oh, you grew up with white people then on the East Coast? Oh, you’re a banana. We don’t need people like you.” And I was just crushed. And I said, “So I can’t volunteer here?” And he goes, “We don’t need people like you.” I left and I was walking down the street crying.

Katayama: So Susan found belonging elsewhere.

Kitazawa: And so I tended that my allies were from a broad range of other people—you know, Latinos, Blacks, poor white people, Filipinos—and I wasn’t that connected with the Japanese American community.

Kitazawa: Kimi Maru had disheartening experiences in her youth, too—only these were outside of the Japanese American community. This led her to connect with her heritage in a different way.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades in.

Maru: And the reason I started taking aikido, actually, was because of an incident that happened to me when I was going to high school.

Katayama: Aikido is a traditional Japanese martial art with a focus on defense and sparing attackers from injury.

Maru: One of my classmates, this white guy who was much larger than me, grabbed me on the wrist and wouldn’t let go. He was, you know, insulting me, saying I don’t even remember what, but it was just a really humiliating experience. And the fact that I couldn’t break free from him, after that I decided I wanted to take self-defense, because I didn’t want anything like that to happen to me again.

Katayama: Aikido wasn’t the only sport that allowed descendants to carve out a space for themselves.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades out.

Katayama: Some turned to activities like baseball or basketball to connect with other Japanese American kids. Kimi’s children played in these basketball leagues competitively.

Maru: When they were young, like five or six, they both got involved in the Japanese American basketball organizations down here. JA basketball is a really big thing down here. I mean, it’s a huge thing. That was a way that they were able to meet a lot of Japanese American friends, because their teammates were primarily Japanese. I think that helped them learn more about not just JA basketball, but just being part of a community of people.

Katayama: Here’s Rev. Michael Yoshii again, who also found community through church sports leagues.

Yoshii: We had a team at our church, and then we played against teams from other churches and Buddhist temples in the East Bay Area. So then I was starting to meet kids from other places in the East Bay and other churches, and then experiencing this whole dynamic of the whole community of Japanese Americans.

Katayama: It was actually through basketball that Alan Miyatake, a Sansei whose family was incarcerated at Manzanar, was able to create an identity separate from his famous family. This fame stemmed from Miyatake Studios, a photography studio founded by Alan’s grandfather, Toyo, prior to World War II.

Soundbed: instrumental music fades in.

Katayama: Toyo was beloved in the Japanese American community in the Los Angeles area, and eventually became the official Manzanar photographer while he was incarcerated there. Toyo reestablished his studio after Manzanar closed, and kept it running for years. Alan now runs things, and the studio has become a multigenerational legacy business. But before Alan took it over, he worked to find his own place.

Alan Miyatake: During my teen years, being around Little Tokyo, I would always hear, “Oh, you’re Archie’s son,” or, “You’re Toyo’s grandson.” And after a while, it was a little irritating. But it hit me enough to say, “Hey, wait a minute, I’m Alan, I have my own identity.” I started around the third grade in some of these Japanese American leagues. I realized that I felt very confident playing basketball. All of a sudden, my goal was to have my own identity. And I think that’s the role basketball played, was that I want to be known as Alan, a good basketball player. I was able to accomplish that after a few years…

Soundbed: instrumental music fades out.

Miyatake: …like hearing people, “Oh yeah, that’s Alan, he’s a basketball nut.” Once I heard that, I thought, Okay, good. Now, now I feel good.

Katayama: The meaning of community space varies across generations. And a few years ago it came full circle for Carolyn Iyoya Irving. At the time, her son was attending the East Bay School for Boys, which resides in part of the First Congregational Church in Berkeley.

Irving: He went there for sixth to eighth grade, and it wasn’t until he was in eighth grade that I learned from my cousin that there’s sort of an outside courtyard where the boys would skateboard.

Katayama: Carolyn found out that there was also historical significance to this place. During World War II, when the US government forcibly removed Japanese Americans from the West Coast, that church served as an assembly point for those local families before being sent to the prison camps.

Irving: And that was evidently where all of the Japanese Americans in Berkeley had to assemble to get on the buses to, to Tanforan. And I didn’t learn that until my son was in eighth grade. And so I remember being like, “Ben, [laughs] you have to talk to your history teacher about this incredible, you know, confluence where you’re here and this is where your own grandmother was, you know, kind of herded into buses and sent off to camps.” And eventually, he actually did incorporate it into what they called their Hero Project, where he had to give a presentation. Which was very touching to me, actually, the fact that, you know, this all happened on the same place.

Katayama: This location, which represented a splintering of the Japanese American community during World War II, has now become a place where Carolyn’s family has been able to make new memories and connections. In effect, her family has been able to reclaim the meaning of this space.

For many descendents, the desire to connect with their Japanese heritage is part of their ongoing search for belonging. And so travel to Japan can be an important rite of passage. It’s also a way of understanding who their parents and ancestors were, as well as where they came from.

Ukai: When I went to Santa Cruz and started studying Japanese, I just found, Oh, this brings in the art, and it makes me understand more things about my grandparents and my parents and myself.

Katayama: Nancy Ukai began to form a deep and lasting relationship with Japan while she was in college at UC Santa Cruz. It felt right for her to explore her heritage through travel.

Ukai: And I ended up going to Japan as an undergraduate.

Katayama: Nancy also ended up returning to Japan after she graduated from college. She stayed for fourteen years. Here’s Kimi Maru talking about her experience traveling to Japan.

Maru: We had a great time. I mean, it was just like so different being in Japan, being in a country where you feel like you’re the majority, right? Yeah, it was just a completely different type of feeling, like going on the trains and buses and bullet train and things. Just being in a situation where everyone around you is Asian [laughs] or Japanese was just a big culture shock.

Katayama: Kimi wasn’t the only person to experience some form of culture shock.

Charbonneau: Being an American girl, you know, I talk a lot. And I was an only child, and so I did have a lot of like energy, and that’s not really how the girls I met were. They had a very like calm energy.

Katayama: That’s Miko Charbonneau.