Tag: history

Trial of Afghan Central Press at UC Berkeley Library

We have set up a thirty-day trial of Afghan Central Press at UC Berkeley Library beginning November 15, 2022.

The vendor description is as follows,

“The Afghan Central Press collection brings together four national, Kabul-based publications of Afghanistan whose long runs and prominence provide a concentrated vantage point for understanding developments in Afghanistan for much of the twentieth century. The English-language Kabul Times is presented alongside Pushto publications Anīs (انیس, Companion), Hewād (هیواد, Homeland), and Iṣlāḥ (اصلاح, Reform).”

The collection provides full-text access to over fifty thousand individual issues in Dari (Persian), Pushto, and English languages.

The Afghan Central Press collection is hosted on Eastview’s Global Press Archive platform.

Track changes: how BART altered Bay Area politics

By William Cooke

“It was just hooted at, the idea that you’d ever get people out of the automobile. They’d never come to San Francisco if they couldn’t drive into San Francisco.” — Mary Ellen Leary, journalist

“The formation of BART is actually one of the funniest things that ever transpired.”

— George Christopher, Mayor of San Francisco

On September 11, 1972, an estimated 15,000 people rode Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) on its very first day of operation. The train system, which at that time was a fraction of its current size, has been a vital service to Bay Area commuters for 50 years now. Those with an interest in the history of the Bay Area’s rapid transit system, or regional planning and public transportation more generally, will find a treasure trove of information in the UC Berkeley Oral History Center’s (OHC) archive.

But BART’s development is much more than a history of a public planning project. It is also a history of the evolution of government and of local versus regional power sharing. The OHC houses oral histories from big and small players in California’s public administration throughout the entire 20th century. The voices of politicians, journalists, city planners, and others reveal that BART’s development brought about a whole slew of questions regarding the proper role of government at all levels and required a great deal of reciprocity.

Mary Ellen Leary, a journalist who got her start with San Francisco News, studied and wrote extensively about urban planning and development in the early 1950s. In her oral history “A Journalist’s Perspective: Government and Politics in California,” she speaks at length about the origins of BART, and the broader development of regional agencies designed to meet the transportation needs of suburban areas, not just cities. “I felt then and still feel that the degree of local participation generated for BART from the first planning funds to the final bond issue was an extremely interesting and important political development.”

Leary says the impetus to begin work on a regional transit system originated in concerns about traffic congestion in the Bay Area. At the time, however, the idea of an alternative to driving in San Francisco seemed absurd. After all, BART would become the first new regional transit system built in the U.S. in 65 years.

But this worry about compact little San Francisco and the automobile launched this idea about rapid transit. And I laugh now about everybody giving BART such a hard time. It was just hooted at, the idea that you’d ever get people out of the automobile. They’d never come to San Francisco if they couldn’t drive into San Francisco.

According to Leary, local businessman Cyril Magnin and San Francisco Supervisor Marvin Lewis were among the first to consider the benefits of investing in a public transit system instead of parking garages. Unlike Los Angeles, the Bay Area could not build enough parking lots and garages to meet the needs of a car-reliant city due to limited space. Leary observes:

At any rate, they got a group of some business people to take seriously the idea of “How is San Francisco going to endure the flood of traffic that’s already coming in from the Golden Gate Bridge and the Bay Bridge? We can’t possibly do it.” The figures were coming out about what percentage of downtown Los Angeles was given over to automobile parking, most of it on the surface. They hadn’t yet begun many multiple-level parking facilities.

Eventually three counties — San Francisco, Alameda, and Contra Costa — committed to the transit system and developed the “BART Composite Report.” This had to be approved by their respective county supervisors in order for a bond measure to be placed on the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District-wide ballot in November of 1962.

In his oral history, longtime Republican politician and former Mayor of San Francisco from 1956–1964, George Christopher, remembers seeking the crucial aye vote of the fifth and still undecided Contra Costa County supervisor, Joe Silva. Silva had been under pressure from his constituents to vote no, because they would not directly benefit from the commuter rail but would bear the high price tag. Without Silva’s vote, the eventual passage of the measure in November and the $792 million bond issue may have been set back by years. According to Christopher, “The formation of BART is actually one of the funniest things that ever transpired,” involving a pre-dawn meeting and donuts.

I called him and I said “Supervisor, you’re the important man here. Now what are we going to do about this? All I’m asking is that you put it on the ballot and let the people decide whether they want it or not…. I said, “What time shall we meet?” He said, “Five o’clock in the morning.”… Sure enough we got up at four o’clock in the morning and we went over to Contra Costa County and finally found this restaurant. It turned out to be a little donut shop with no tables, no tables whatever, and we all sat around the counter. Here were all the teamsters, the truck drivers listening to every word we had to say…. I don’t know how many donuts we had, but we certainly filled ourselves.

Many hours and donuts later, Christopher had earned Silva’s crucial “yes” vote in support of the regional rail system. Christopher’s oral history is part of the Oral History Center’s “Goodwin Knight-Edmund G. ‘Pat’ Brown, Sr. Oral History Series,” which covers the California Governor’s office from 1953 to 1966, and is a gold-mine of fascinating anecdotes on city planning and transportation issues during that crucial decade.

Even before the bond issue was put on the ballot and approved in 1962, a consequential battle for regional power over transportation, including BART, was fought, ultimately resulting in a victory for local influence in this regional system. This battle was reflected in the approximately three-year long struggle between the Golden Gate Authority (GGA) and its younger competitor, the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG), for control over the planning and operation of transportation infrastructure in the region. Several oral histories from the Oral History Center discuss the importance of ABAG, which refers to itself as “part regional planning agency and part local government service provider.” In the oral history titled “Author, Editor, and Consultant: A Participant from the Institute of Governmental Studies,” Stanley Scott, a research political scientist at UC Berkeley, explains:

It came more from the large business interests, the Bay Area Council, with Edgar Kaiser being the chief proponent and front man, I guess you’d say, to create a Golden Gate Authority. That would incorporate the ports, the airports, and the bridges, the bridges being brought in essentially because they were very profitable organizations. So that one kind of came in, you might say, from the side, but at the same time, also involving regional restructuring.

This really upset the cities and counties, and quite a few others. A lot of people were concerned about it. A lot of people were concerned about just latching on to the bridges and tying them in with the airports and seaports. What are we going to do about all the other transportation problems? There was a great deal of concern.

It also exercised cities and counties that just did not want a major authority coming in from off the wall, so to speak. They began organizing themselves, and that was, in part, the genesis of ABAG. It was not the only reason for ABAG’s creation, but it provided substantial push in that direction. It had a lot to do with it. It scared the local people. That would have been in ’58, ’59, and ’60, that the Golden Gate Authority idea was kicked around. It was over a period of at least two years, and it could have been three, before it finally bit the dust.

T.J. Kent also addresses this theme about local influence and power sharing — with a focus on the role of ABAG — in his oral history, “Professor and Political Activist: A Career in City and Regional Planning in the San Francisco Bay Area.” Kent was a prominent city planner under San Francisco Mayor Roger Lapham in the 1940s, a deputy mayor for development under Mayor John Shelley in the 1960s, served on the Berkeley city council in the 1950s, and was a founder of UC Berkeley’s Department of City and Regional Planning.

According to Kent, former Mayor George Christopher opted to keep San Francisco out of ABAG because he felt that San Francisco was too important a player in the region to enter into an equal-representation regional government. His successor, Mayor John F. Shelley, reversed that policy, bridging the way to cooperation between the Bay Area’s largest city and the influential agency.

Shelley, with the board of supes [supervisors] backing him, he brought San Francisco into ABAG and appointed me as his deputy on the ABAG executive committee. I also served as the mayor’s deputy on the ABAG committee on goals and organization….The Committee prepared the regional home rule bill that was adopted by ABAG in 1966… It called for a limited function, directly elected, metropolitan government. That’s the key report.

Indeed, the publication of the Regional Home Rule and Government of the Bay Area report marked a huge milestone in the actualization of BART. ABAG, which was granted the authority by the State of California in 1966 to receive federal grants, included BART in the four elements of its metropolitan plan. Kent explains:

The first is the central district, enlarged and unified and focused in San Francisco; the second is a regional, peak-hour commuter transit system, which is BART and AC transit, plus the other transit systems serving San Mateo County, San Francisco and Marin and Sonoma counties; third is the open space system, to keep things from sprawling and for basic environmental reasons; and the fourth was comprised of the region’s residential communities, which shouldn’t get too dense, too overbuilt.

ABAG’s ability to receive and use federal money would prove vital to BART’s construction and continued operation. Furthermore, city and county representation on ABAG’s board — as opposed to zero locally elected officials in the defunct Golden Gate Authority — meant that cities likely had more of a say in the planning of BART than they would have had under the administration of the GGA.

Kent, then a Berkeley city councilmember, helped write the ABAG bylaws that balanced regional and local power. Kent believed in the importance of assigning enough power to regional agencies and districts like ABAG and BART, while also maintaining local autonomy. According to Kent — who throughout his oral history stresses the need to protect home rule wherever possible — counties that opted to stay in the Bay Area Rapid Transit District sometimes felt that the District was too restrictive or overbearing. But as a regional representative government with limited authority, conflicts were eventually solved. Kent remembers the back-and-forth between BART and Berkeley prior to the bond issue passing in 1962.

But those [counties] that were left in [the District], there were major battles in the BART legislation because the BART legislation had to give that agency that power and right. I was on the Berkeley council at the time and the battles were serious. There were many things that BART was required to do in consulting the cities and counties before the bond issue was proposed and voted on in 1962 and even after, which I think was good. They required BART to deal with Berkeley as an equal when Berkeley said, “We think—.” Berkeley got tremendous concessions from BART before the bond issue. You may not realize it, but the initial 1956 BART plan for the Berkeley line had it elevated all the way through downtown. Berkeley fought back before the bond issue vote of ʼ62 and got the middle third put underground.

Those counties that decided to stay in the District and cooperate with BART during its construction had a say in the decision-making process. Perhaps due to that fact, the 1962 district-wide bond issue surpassed the required 60% approval threshold, a result that came as a surprise to many political experts. Litigation and negotiations ensued with cities and counties across the Bay Area in the years that followed. But without the initial bond issue, BART could not have even begun construction.

Mary Leary observed that the impetus to create a regional, commuter rapid transit system — as well as the process of planning BART — did much to encourage local participation in politics. Even though ABAG was a regional entity with certain powers over local governments, Leary says that the agency allowed local governments a say in BART’s planning.

I think it was not unrelated that during this same era of local sharing in BART plans on a regional basis the Supervisors Association and the League of California Cities together launched ABAG, Association of Bay Area Governments, a voluntary group of cities and counties to discuss regional problems. It did not become a real regional government. In fact, I always felt it was created by those two groups to thwart moves towards regional government and to make sure cities and counties maintained their own strong voices. But it has been a significant forum and I think cooperation of the various governments around the Bay in planning BART gave it a good start. Interestingly, when planning got underway for where BART’s lines should run and stations should be, this became the first regional planning ever undertaken and local communities could see as some did that they were planning a sewer outfall just where the next-door neighbor town was planning a beach resort, that sort of thing.

In her oral history, Leary also noted a change in public perspective about public transit — away from the idea that no one would visit San Francisco if they couldn’t drive, to voters actually rejecting federal funds for a freeway connecting the Golden Gate and Bay bridges — and the relationship of BART to that.

Anyway, there was a good deal of political pride in the area that they had shared in developing BART from the very start, and it was part of the system’s success. Most other cities sat back and waited for Washington to provide funds for transit. Los Angeles never could get that much regional support. Of course, about that same time San Francisco was so supportive of the transit idea it rejected federal money for a freeway connection between the Golden Gate Bridge and the Bay Bridge. That really stirred a lot of national attention, saying “no” to millions or maybe billions.

Those interested in exploring the history of BART further, or learning more about the central themes of its history — local and regional government power sharing in the Bay Area, effective organization of regional governing bodies, and local participation in city planning, to name a few — can find much more in OHC’s numerous projects and individual interviews. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria from the OHC home page.

William Cooke is a fourth-year undergraduate student majoring in Political Science and minoring in History. In addition to working as a student editor for the Oral History Center, he is a reporter in the Sports department at UC Berkeley’s independent student newspaper, The Daily Californian.

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library has interviews on just about every topic imaginable. You can find the interviews mentioned here and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. We preserve voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page.

Related Oral History Center Projects

Covering the years 1953 to 1966, the Oral History Center (then the Regional Oral History Office) began the Goodwin Knight-Edmund G.Brown, Sr., Oral History Series of the State Government History Project in 1969. It covers the California Governor’s office from 1953 to 1966 and contains 84 interviews with a diverse set of personalities involved in Californian public administration. Topics include but are not limited to the rise and decline of the Democratic party, the impact of the California Water Plan, environmental concerns, and the growth of federal programs. This series includes the multivolume “San Francisco Republicans,” which includes the oral history of George Christopher, “Mayor of San Francisco and Republican Party Candidate.”

The San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge Oral History Project, launched in May of 2012, is a collection of 15 interviews that cover the construction of the Bay Bridge, maintenance issues, and the symbolic significance of the bridge in the decades after its construction. The majority of interviewees in this project spent their careers working on or around the bridge as architects, painters, toll-takers, engineers and managers, to name a few.

The California Coastal Commission Project traces the development of the only California commission voted into existence by the will of the people, from the campaign for Proposition 20 that created the agency in 1972 to the various development battles it confronted in the decades that followed. These interviews document nearly a half century of coastal regulation in California, and in the process, shed new light on the many facets involved in environmental policy.

Listen to the “Saving Lighthouse Point,” podcast, a collaboration between the OHC and the Bill Lane Center for the American West at Stanford University. “Saving Lighthouse Point” tracks the successful effort by citizens of Santa Cruz, with the support of the California Coastal Commission, to block the development of a bustling tourist and business hub on one of the last open parcels of land in the city.

Related Resources from The Bancroft Library

City and regional planning for the Metropolitan San Francisco Bay area, Kent, T. J., 1963. Bancroft Library/University Archives, Bancroft ; F868.S156K42

Open space for the San Francisco Bay area; organizing to guide metropolitan growth, Kent, T. J., 1970. University of California, Berkeley. Institute of Governmental Studies. Bancroft Library/University Archives. Bancroft ; F868.S156.57.K4

Regional plan, 1970–1990 – San Francisco Bay region, Association of Bay Area Governments, 1970. Bancroft Library/University Archives. Bancroft Pamphlet Double Folio ; pff F868.S156.8 A82

The BART experience: what have we learned? Webber, Melvin M.; University of California, Berkeley. Institute of Transportation Studies. 1976. Bancroft Library/University Archives. UC Archives ; 308m r42 W372 b

[Webinar-UC Berkeley Library] Afghanistan: One Year Later!

We invite you to attend a ninety-minute Afghanistan-related webinar sponsored by multiple Area and International Studies-related centers and Institutes (CMES, ISAS, ISEEES, IEAS) and the library at UC Berkeley.

Title of the webinar: Afghanistan: One Year Later!

Date: August 16, 2022

Day: Tuesday

Time:

11:30 am to 1 pm PDT

1:30 pm to 3 pm CDT

2:30 pm to 4 pm EDT

——————————

7:30 pm to 9 pm UK time

11:00 to midnight Kabul time

————————-

Registration

The webinar is free and open to all with prior registration: http://ucberk.li/3r3

——————–

Speakers

- PROFESSOR CARTER MALKASIAN, PH.D., Chair, Defense Analysis Department, Naval Postgraduate School

- PROFESSOR SHER JAN AHMADZAI, Director of the Center for Afghanistan Studies, University of Nebraska at Omaha

- PROFESSOR DIPALI MUKHOPADHYAY, PH.D., Hubert H. Humphrey School of Public Affairs, University of Minnesota

- PROFESSOR SHAH MAHMOUD HANIFI, PH.D., Department of History, James Madison University

- Moderator: Dr. Liladhar R. Pendse, Librarian, UC Berkeley

A special note of gratitude to the Library’s Communications Team, Professors Asad Q. Ahmed of Middle Eastern Languages & Cultures, Wali Ahmadi of Middle Eastern Languages & Cultures, and Munis Faruqui of Department of South and Southeast Asian Studies, Central Asia Working Group at the IEAS.

Title IX in Practice

How Title IX Affected Women’s Athletics at UC Berkeley and Beyond

By William Cooke

Title IX, a federal civil rights law passed in 1972 that amended the 1964 Civil Rights Act, prohibits discrimination based on sex at any educational institution that receives federal funding. While it pertains broadly to all forms of sex-based discrimination, the law arguably precipitated the most change in the arena of intercollegiate athletics. In any case, the passage of Title IX half of a century ago represents perhaps the single most significant event in the history of intercollegiate athletics in the United States, and was a major victory in the realm of civil rights for women.

The UC Berkeley Oral History Center houses a rich collection of interviews between oral historians and a diverse set of individuals that touch upon Title IX. In these interviews, influential figures across many different fields including intercollegiate sports, academia, and politics provide their insight into Title IX and its implementation over the course of the past fifty years.

“Title IX was fantastic for women in politics. It has created a generation of risk takers, in the best of ways.” —Mary Hughes, political consultant

Here are just a handful of voices that mention the transformative 1972 law across a few of the Oral History Center’s many collections.

In her oral history, Mary Hughes, a long-time Democratic political consultant who once served as the executive director of the California Democratic Party, recognizes the underappreciated role of Title IX and gender inclusion in sports in preparing women for positions of leadership in politics.

I attribute a lot of their success to Title IX, and here’s why: Title IX was fantastic for women in politics, both those who have supported and strategized to get women into office, and the women who have run. There is a difference between the women who grew up playing sports from a very young age and the women who did not… Their ability to be competitive without an irrational fear of failure is one of the most freeing things I’ve ever seen. I love these young, competitive women, and I hope we hold on to this, because it has created a generation of risk takers, in the best of ways, in the best of ways.

As a result of Title IX’s passage at the start of the decade, Luella Lilly became the first director of Women’s Athletics at Cal in 1976. The promise of equal opportunity for women in collegiate sports did not — and still does not — mean that men’s and women’s sports were resourced equally. One of Lilly’s priorities as director was to establish scholarships for female athletes for the very first time.

And so what I did was—they gave me—I think it’s $6,740 dollars, which was— tuition and fees were $670, I think they were, something like that. Anyway, it gave me ten tuition and fees at that point in time. So I gave them to each of the sports that could give scholarships, and had the coach divide it so that whatever way they wanted to. If they wanted to give somebody a full ride that was up to them, but if they wanted to split it among all— they could do anything they wanted to in their particular sport. But I just wanted to be able to mark the check that said we had them.

Joan Parker, a former Cal women’s basketball, softball, volleyball and tennis coach as well as assistant and associate athletic director in the Women’s Athletic Department for 13 years, praises Lilly for championing women’s sports when it was underfunded and underappreciated in the decades following 1972.

Lue came in, it was just—I was totally impressed with how she made things happen with so little money. It was just ridiculous when you compared our budgets to others… But Title IX definitely— and I think a lot of people didn’t understand it. A lot of outside— like our boosters and things like that, weren’t as aware of it. I think it was more of an internal pressure that at some point you’re going to be held accountable, and so you’d better start something in motion.

But while revolutionary and long overdue, Title IX also had some adverse, unintended consequences that still trouble university athletic programs.

Roberta Park was a supervisor of Physical Education at UC Berkeley until she stepped down after the passage of Title IX. She later served as the chair of the Department of Physical Education between 1982 and 1992. Park was a tireless champion of physical education programs and, in her oral history, makes it known that Title IX indirectly brought about a whole slew of repercussions for recreational sports programs that once benefited the entire student body. For one thing, elite athletes were prioritized over women’s widespread inclusion in sports.

I believed, and still believe, that colleges and universities (and high schools as well) should provide extracurricular sports programs for all interested women and girls, not just for the small number of the best athletes. Unfortunately, what evolved was an emphasis on the latter and an approach that gives the athletic program for a small number of the women athletes precedence over everything else… “We want to focus only on the women’s “varsity” basketball team, etc.” Well, if you put all of your efforts into a small number of the best athletes and you forget about all the others, what have you done? And that’s exactly what has happened. That’s exactly what has happened.

Another repercussion of Title IX was the merging of Physical Education and Intercollegiate Athletics departments at major universities across the country. This meant that sports programs for women were subsumed into intercollegiate athletics programs, sometimes causing women to lose higher-level administrative positions to men. After the passage of Title IX, Park pushed for the creation of a separate department of intercollegiate sports for women at UC Berkeley, which she argued was crucial to protecting female representation in intercollegiate athletics administration.

The emerging intercollegiate athletic sports for women, which used to be under the direction of Women’s Athletic Association or Women’s Recreation Association (which were directed by females, usually physical educators) were now all being moved over into Intercollegiate Athletics. With very, very few exceptions (in fact, I can think of none except at women’s colleges) all the Directors positions were taken over by men: And one of the things that I said was, “Well, okay, men have been doing this longer, and fair enough, but if Title IX is supposed to be about equity, what about the equity of women as the directors?”… So they finally decided, and I— I guess pushed is the right word, to the extent that I thought was appropriate, in the direction of a separate unit for women.

Another issue that arose was in the way that equal opportunity was interpreted. Charles Young, the Chancellor of UCLA between 1968 and 1997, witnessed firsthand the evolution of Title IX’s implementation at a major Division I university from before its conception up until the late 1990s. Young found the policy of creating an equal number of men’s and women’s programs to be misguided and at times counterproductive.

The principles of Title IX are fantastic but I think the major problem was that they took equivalence or took opportunity. Instead of opportunity they looked at the balance. And so you create a women’s sport to get in balance and there isn’t anybody who wants to play it. So then you have to go out and recruit people to come play it. Well, the principle should have been, are you providing as much opportunity for the women students as you are for the men. But it’s driven up the number of sports. It’s caused good sports to be eliminated at UCLA.

Former UC Berkeley Athletic Director John Kasser, who served as AD between 1993 and 2000, claims in his interview that Title IX was unfair to the supporters of Cal men’s sports who had to subsidize women’s sports in order to continue funding men’s sports at a competitive rate.

But see, that’s the thing when we—I don’t blame—Title IX was absolutely right and has been wonderful for women’s athletics, but nobody ever came with a financial plan… And so they expected Men’s Athletics to raise the funds to support Women’s Athletics. And so when you talked about it—you couldn’t say, “Well, that’s not fair.” But it wasn’t fair. It wasn’t fair.

One could argue that Title IX’s pitfalls speak more to the systemic issues that have prevented female student athletes from enjoying the same access to resources as men and not, as some might argue, to the failure of the law itself to protect “fairness.” The historical disadvantages of women in college sports made growing pains inevitable and even healthy for a field that has been dominated by men from the outset.

Now, fifty years after Title IX’s inception, these interviews help us recognize not only that progress is never perfect or steady, but also just how much progress has been made in the way of gender equality in intercollegiate sports thanks to the ongoing struggle of marginalized groups for the recognition of their civil rights.

Find these and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, keyword, and several other criteria.

William Cooke is a fourth-year undergraduate student majoring in Political Science and minoring in History. In addition to working as a student editor for the Oral History Center, he is a reporter in the Sports department at UC Berkeley’s independent student newspaper, The Daily Californian.

About Title IX

Title IX of the Education Amendments to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed into law on June 23, 1972, by President Richard M. Nixon: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Related Resources from The Bancroft Library

The Bancroft Library has hundreds of materials related to athletics in California and beyond. Here are just a few.

See the Oral History Center’s (OHC) project, “Management of Intercollegiate Athletics at UC Berkeley: 1960–2014” which includes more than forty interviews with chancellors, athletic directors, faculty members, donors, and others involved in athletics at Berkeley. See also OHC’s “Education and University of California — Individual Interviews” featuring more than 150 faculty, senior administrators, and staff.

University of California, Berkeley. Department of Women’s Intercollegiate Athletics records, 1976-1993. UC Archives (NRLF) CU-566

A celebration of excellence : 25 years of Cal women’s athletics. UC Archives Folio 308m.p415.c.2001

Title IX self study, University of California, Berkeley, approximately 1977. UC Archives (NRLF) CU-509

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library has interviews on just about every topic imaginable. You can find the interviews mentioned here and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. We preserve voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public.

Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page.

Primary Sources: Books of Modern China & Picture Gallery of Chinese Modern Literature

The Library has recently acquired Books of Modern China (1840-1949), 中国近代图书全文数据库, a collection of more than 120,000 Chinese books published in Mainland China. Many of them are unique titles and are only available through this digital collection from the Shanghai Library.

The Picture Gallery of Chinese Modern Literature (1833-1949), 图述百年—中国近代文献图库 contains more than one million images that have been collected from books, periodicals, newspapers, and old photos held by the Shanghai Library.

These resources have been added to the History: Asia guide.

Objectivity and Subjectivity in Oral History: Lessons from Japanese American Incarceration Stories

Sari Morikawa is an intern at the Oral History Center (OHC) of the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. She is a Mount Holyoke College history major with a keen interest in American history.

This fall, I had an opportunity to work on the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project (JAIN) with OHC interviewers Amanda Tewes, Shanna Farrell, and Roger Eardley-Pryor. For this project, I identified oral history interviews discussing Japanese American incarceration during World War II in the OHC’s collections. Later, I compiled and constructed an annotated bibliography for the team, as well as for future researchers. At the same time, I engaged with and acquired knowledge of basic oral history theories and methodologies. Through this project, I had a chance to reflect upon the idea of intersubjectivity and contemplate how this concept plays out in a real oral history project. This entire experience caused me to wonder how my own subjectivity—including my background as a Japanese woman and not an American citizen—might influence how I interpret and share these oral history narratives on Japanese American incarceration.

For the first phase of my internship, I engaged with prominent oral historians’ scholarly work and learned basic oral history methodologies and practices. In particular, the idea of intersubjectivity struck me. In oral history, intersubjectivity means that both the interviewer’s and narrator’s subjectivity, or identities and lived experiences, impact their interpretations of memories and shape the interview they co-create. In particular, Kathleen Blee’s article, “Lessons from Oral Histories of the Klan,” was very influential for me. In this article, Blee sheds light on the idea that historians need to grapple with how to tell people’s stories while considering their own social identities and perspectives, especially when they disagree. After briefly discussing the author’s main argument, Amanda asked me a question, “Do you think history can be objective?” This question struck me. At that point, I believed that objectivity in history was important to avoid romanticization of the past. For example, in order to justify the incarceration plan, the U.S. federal government conceptualized Manzanar as a “holiday on ice” and shared this interpretation with the general public. As a result, some of the oral history transcripts demonstrate (particularly white) narrators’ misunderstanding and misinterpretation of Japanese Americans incarceration. Thus, I believed that history should be neutral to prevent romanticization. Yet, my views on objectivity and intersubjectivity changed as I started writing the annotated bibliography and engaged more with oral history theory and methodology.

By the beginning of October, we started working on an extensive annotated bibliography. I identified oral history transcripts which discuss Japanese American imprisonment during World War II. It turned out Japanese Americans’ incarceration experiences were too diverse to generalize. It was wonderful to see that narrators who discussed the incarceration ranged from formerly incarcerated deaf family members to the War Relocation Authority officials to a fisherman who delivered fish to incarceration centers. I recognized how diverse their voices are and realized that the stories that we tell are not objective at all. Thus, history cannot be objective. For example, some formerly incarcerated Japanese Americans expressed their bitter feelings that life in incarceration camps was shocking and traumatizing. Some of them, like Nancy Ikeda Baldwin, even said that these experiences decreased their performance in school after their incarceration. On the other hand, others said that the incarceration camps were enviable experiences. One generation later, Eiko Yasutake confessed, “I was kind of a little jealous when you went to the camps, because that, for kids, was that side of it, that they were all together and kind of had that playtime if you will.” In fact, so many photographs from this time highlight Japanese Americans’ agency. Jack Iwata’s work uncovers Japanese Americans hosting beauty pageants, emphasizing Japanese Americans’ power to make the most out of their circumstances. This wide array of recollections, even among Japanese Americans, confused me. However, it made me contemplate how I would utilize the idea of intersubjectivity to share this nuanced and complex history with people who don’t really know about these incarceration experiences.

The question of how I would interpret these stories and share them with people who are unfamiliar with this topic led me to another question: how my identity as Japanese would impact interpretations of Japanese American incarceration. As a person who partially shares the same heritage and cultural background, I felt a sense of familiarity and interacted with interview transcripts with care. Encountering some of the Japanese words in oral history interview transcripts that don’t quite translate into English, such as ‘gaman‘ and ‘shikataganai,’ I felt a cultural connection to Japanese American prisoners. When someone discusses that formerly incarcerated Japanese Americans are hesitant to talk about their experiences, I recognize how Japanese culture made them react that way. My own subjectivity helped me grapple with these Japanese Americans’ incarceration stories. At the same time, I learned that I should also step back from my own subjectivity. Some of the Chinese and Filipino Americans’ transcripts on this topic allowed me to tackle this idea. Caroline and Frank Gwerder said, “[Filipinos] were fearful of what the Japanese might do.” These interviews reminded me of how Japanese imperialistic and super nationalistic policies and how they implanted fear on other Asian Americans and reshaped U.S. homeland politics. Since then, I felt more cautious about my national identity, in particular as a person coming from a country with this imperialistic past. That adage that “winners write history” nicely illustrates how imperialists write and rewrite history and leave behind the perspectives of marginalized communities. Recognizing this, I became to be more mindful about valuing the stories of incarcerated Japanese Americans.

Throughout this process, I realized that the inner dialogue between my identity, my interpretation of these oral history interviews, and how I would disseminate them to a larger audience is all subjective. Historians cannot avoid being subjective. In order to best reflect these interviews through my annotated bibliography, I would highlight their plight caused by the government’s racially discriminatory plan and Japan’s imperialistic military policy. Yet, more importantly, I would also emphasize incarcerated peoples’ agency and adoption of “gaman.” Utilizing my shared culture and history, as well as acknowledging the imperialistic past that my country made, I will utilize the oral history as bottom-up narratives to overturn the romanticized past.

Find out more about the oral histories mentioned here from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Mexico and the conquest of Tenochtitlán (May 1521-2021)

The month of May this year marks the five-hundredth anniversary of the fall of Tenochtitlán (1521-2021). The tragedies that unfolded in the continent after the conquest are well documented. However, as far as the accounts of the fall of the Tenochtitlán are concerned, there are several different opinions and disagreements. What about the letters of Hernán Cortés? Here is the second letter from the WDL

Also on the archive.org, we see a digitized copy of JCB’s 1552 Francisco López de Gómara’s “La historia general de las Indias, y todo lo acaescido enellas dende que se ganaron hasta agora. ; y La conquista de Mexico, y dela Nueua España.”

Also on the archive.org, we see a digitized copy of JCB’s 1552 Francisco López de Gómara’s “La historia general de las Indias, y todo lo acaescido enellas dende que se ganaron hasta agora. ; y La conquista de Mexico, y dela Nueua España.”

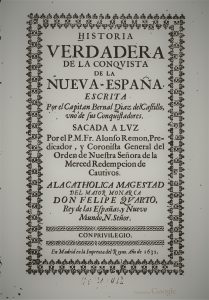

What are some of the primary sources that are now open access and can be used to inform us about the events that unfolded five hundred years ago? One such source is Bernal Díaz del Castillo’s is work, “Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España.” On the right, one sees a title page of the 1632 imprint of the same that is available in Google Books.

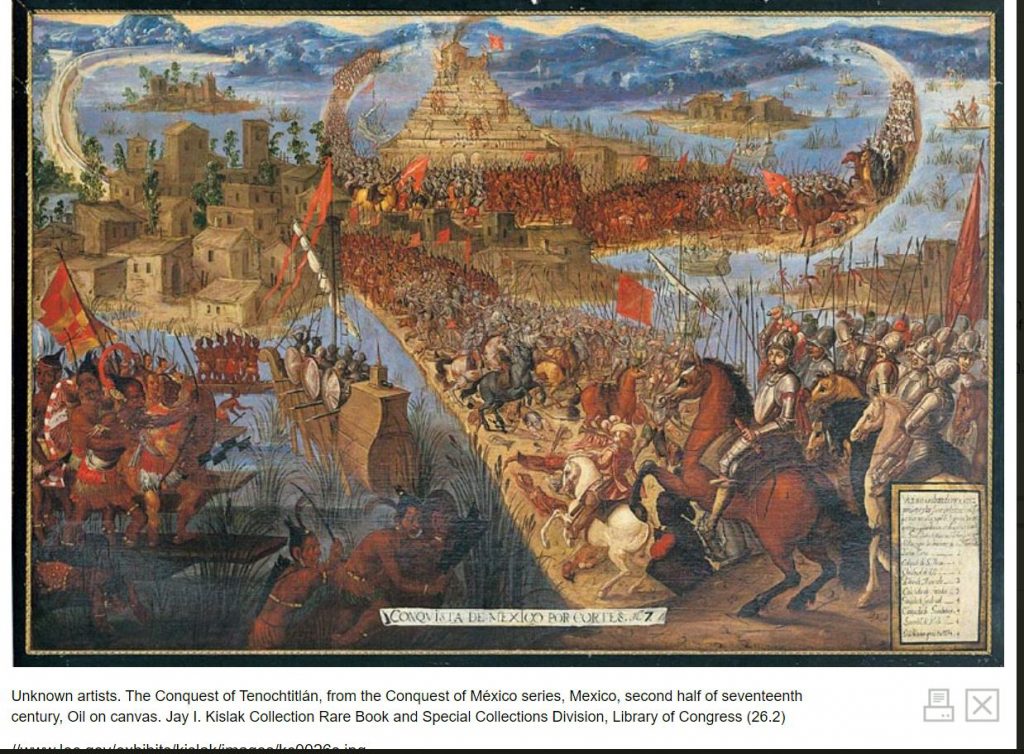

While some often use paintings from the late 17th century to depict and describe the fall of the capital of the Aztecs, these are often functions of the artistic license, and in some cases, we do not know who could have painted them.

The painting, such as the one below, is one example from the Library of Congress’ collection. Can images narrate the nuanced past accurately? These images are from the LOC’s exhibition and also in Wikimedia commons.

But where are the voices of those who were conquered but not vanquished? Can we rely on Codex Florentino as one perhaps contested source? The WDL (from the collection of Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana) has made it available for the readers to judge the process that began with the conquest of Tenochtitlán. The LOC’s description reads, “Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España” (General History of the Things of New Spain), as the Florentine Codex is formally known, is an encyclopedic work about the people and culture of central Mexico compiled over a period of 30 years by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún (1499–1590), a Franciscan missionary who arrived in Mexico in 1529, eight years after completion of the Spanish conquest by Hernan Cortés. The text is in Spanish and Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs. Its 12 books, richly illustrated by indigenous artists, cover the Aztec religion and calendar, economic and social life, Aztec history and mythology, the use of plants and animals and the Spanish conquest as seen through the eyes of the native Mexicans.”

I leave you with unfinished thoughts. Can a manuscript tell the story? See for yourself by watching Getty Researcher Institute’s five-part series. And with Taibo’s, “¿Historia para qué?”I love Paco Ignacio Taibo II’s argument about who we are? And his questioning of sanitization history where Cortes and Cuauhtemōc are dancing La Sandunga.

Library Database Trial: Russian-Ottoman Relations (1600-1914)-Brill-Parts I, II, III and IV

We are pleased to announce a library trial of Brill’s four parts database-Russian-Ottoman Relations.

The resource’s self-description is as follows, “Brill in cooperation with the National Library of Russia in St. Petersburg, for the first time brings together a unique collection of rare primary sources on a dynamic part of the history of Turkey, Russia, the Middle East, and Western Europe: Russian-Ottoman Relations. They include publications of relevant government documents, diplomatic reports, travel accounts that provided new details about hitherto relatively unknown regions, and fiercely political (and polemical) tracts and pamphlets designed to rally public support for one power or the other. Published across Europe over a period of two centuries, these sources provide detailed insights not only in the military ebb and flow of Russian-Ottoman relations but also in their effects on European public opinion. ”

The trial is set to start today and end on April 8, 2021

Please authenticate using your proxy or VPN credentials if you are trying to access the resource from an off-campus location.

This series currently consists of 4 parts. Please click on each hyperlink to access the full-text of each resource.

The Origins, 1600-1800

• Part 1: The Origins 1600-1800

Shifts in the Balance of Power, 1800-1853

• Part 2: Shifts in the Balance of Power, 1800-1853

The Crimean War, 1854-1856

• Part 3: The Crimean War 1854-1856

The End of the Empires, 1857-1914

• Part 4: The End of the Empires, 1857-1914

Dispatch from the OHC Director, April 2020

From the OHC Director, April 2020

I’ve been thinking a great deal of late about what it means to live a life connected or disconnected or perhaps something in between. I suspect I’m not alone in pondering these states of being — a kind of remote engagement that itself feels a little bit like connection.

Oral history is about many things: listening, documenting, questioning, recording, explaining. I think connection is always key to the work that we do as oral historians. But like many other operations, including basically all non-medical research projects that involve humans, our work conducting interviews is largely shut-down while we consider how best to forge ahead.

My colleagues and I have always valued the importance of the in-person, face-to-face interviewing experience. We regularly travel across the country at some considerable expense just so we can be in the same room with the person we are interviewing. We have found this time in close proximity with our narrators to be priceless. Not only does this allow us to shake hands, look eye-to-eye, and gauge body language just before and during the interview, but also these are practices that, until recently, have been second nature — we usually do them without thinking much about it. There really is an unconscious kind of dance that happens, especially when meeting someone for the first time, that in most instances results in a spontaneously choreographed fluidity that can carry the ensuring interview through fond memories and bad. Because of this, up to this point, only when it really was impossible to meet in person have we conducted an interview over the phone or online.

But times change. The current health crisis has profoundly rearranged social relationships, and likely for some time into the future. (Dr. Fauci even suggested that we rethink the practice of shaking hands, which, I’ll admit, makes me sad.) The Oral History Center staff have been scattered now for over a month. But we have endeavored to not lose touch with one another. Thanks to multifarious technological options, we have easily transitioned our weekly staff meetings online. We use either Google Hangouts or Zoom and, so far, everyone has used video, so we get to hear each other’s voices and see faces too. We sometimes have agenda items that require lengthy discussion, at other times we simply check in with each other about work but also about “how things are going.” We live in different settings so people have different challenges and we do our best to touch on those. I also chat every week with each of my colleagues individually and I’m very pleased to know that my colleagues have been meeting with each other, doing their best to push projects forward. The success of these virtual meetings, and, well, the zeitgeist, inspired me to set up virtual happy hours with friends and family. My family lives across the country and it’s been probably four years since we’ve been in the same room together but for the past two weeks we’ve all gathered online to check in, tell stories, have some laughs, get serious and, of course, get photobombed by various kids and dogs. We don’t escape the underlying gravity of the current situation, but this hasn’t stopped connection — in some real ways it has promoted it.

So, with this in mind, we are exploring the options for bringing our oral history back to life by bringing it online. We’re currently testing out various options for video and audio recording, paying close attention to everything from quality of recording to ease of use (considering that most people we interview don’t fit within the “digital native” demographic). We also are sensitive to the dimension of personal connection, rapport, and understanding, but given recent experiences “at” home and “in” the office, we have reason to be optimistic. The reasons for going online are not only about opportunity, they are much deeper and in some ways quite profound: every day, every month that passes, we lose an opportunity to interview someone who should have had the opportunity to tell their story. In fact, we just learned the very sad news that artist and advocate of Black artists, David Driskell, passed away due to complications from COVID-19. This was a man with a story to be told — and thankfully, with our partners at the Getty Trust, we conducted his oral history last year. We simply cannot wait out this epidemic and let it steal stories along with lives.

The second profound reason is related to something I’ve mentioned rather delicately here in the past: that the Oral History Center is a soft-money institution. What that means is we are basically a non-profit that earns its money (allowing us to do our work) by conducting interviews. The longer we are prevented from conducting oral histories, the more precarious our position becomes. We hope for but do not anticipate relief from the university, the state, or the federal government. All we want is to resume the good work of documenting our shared and individual experiences in times of growth and times of challenge — to continue the work that we’ve done for the past 66 years.

As we consider the path ahead, the Oral History Center staff continues to work vigorously albeit remotely. We’re finishing the production process on dozens of interviews that have been conducted already — that is, writing tables of contents, working with narrators on edits for accuracy and clarity, creating the final transcripts for bound volumes and open access on our websites. We continue to process original audio and video recordings so that they can be uploaded to our online oral history viewer. We’re writing blog posts about oral history and producing podcasts, including our newest and very topical season, Coronavirus Relief. Plus in addition to the regular work, we’re using this opportunity to focus on long desired projects: We’re creating curriculum for high schools; we’re writing abstracts for old interviews that never had them; and we’re using this time to think about new projects and write grant proposals so that when the time comes, we’ll be ready to go full steam ahead.

Check back here next month for more on our efforts to move oral history online. We’ll share our results publicly as many others are venturing into this domain too — and have themselves made important contributions to the conversation (I especially recommend checking out the free Baylor / OHA webinar on “Oral History at a Distance”). Until then, we sincerely hope that everyone this newsletter reaches stays safe, healthy, and able to remain connected to those who are important to you.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library

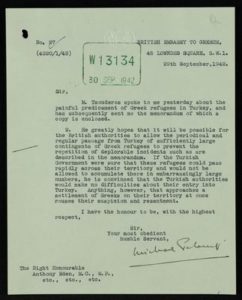

Trial access: Refugees, Relief, and Resettlement: Forced Migration and World War II

Until March 31, the Library has trial access to Refugees, Relief, and Resettlement: Forced Migration and World War II, which “chronicles the plight of refugees and displaced persons across Europe, North Africa, and Asia from 1935 to 1950, bringing together over 650,000 pages of pamphlets, ephemera, government documents, relief organization publications, and refugee reports that recount the causes, effects and responses to refugee crises before, during and shortly after World War II.” The records are sourced from the foreign and colonial office files in the U.K. National Archives, the U.S. State Department from the National Archives Records Administration, the British India office collection from the British Library, and the archives of World Jewish Relief.

Until March 31, the Library has trial access to Refugees, Relief, and Resettlement: Forced Migration and World War II, which “chronicles the plight of refugees and displaced persons across Europe, North Africa, and Asia from 1935 to 1950, bringing together over 650,000 pages of pamphlets, ephemera, government documents, relief organization publications, and refugee reports that recount the causes, effects and responses to refugee crises before, during and shortly after World War II.” The records are sourced from the foreign and colonial office files in the U.K. National Archives, the U.S. State Department from the National Archives Records Administration, the British India office collection from the British Library, and the archives of World Jewish Relief.