Tag: environmental history

Primary source: Environmental History: Conservation and Public Policy in America, 1870-1980

The Library has gained access to the online archive “Environmental History: Conservation and Public Policy in America, 1870-1980” thanks to the Institute for Governmental Studies Library’s contribution of nearly 2,000 items to this collection.

The Library has gained access to the online archive “Environmental History: Conservation and Public Policy in America, 1870-1980” thanks to the Institute for Governmental Studies Library’s contribution of nearly 2,000 items to this collection.

A detailed description from the vendor’s website:

Starting in the late nineteenth century, in direct response to the Industrial Revolution, forces in social and political spheres struggled to balance the good of the public and the planet against the economic exploitation of resources. Environmental History: Conservation and Public Policy in America, 1870–1980 chronicles various responses in the United States to this struggle through key primary sources from individual activists, advocacy organizations, and government agencies.

Collections Included

- Papers preserved at Yale University of George Bird Grinnell, a founding member of the Boone and Crockett Club, one of the earliest American wildlands preservation organizations; a founder of the first Audubon Society and New York Zoological Society; and editor for 35 years of the outdoorsman magazine Forest and Stream, which played a key role as an early sponsor of the national park movement and Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918.

- Records housed at the Denver Public Library of the American Bison Society, an organization that sought to save the American bison from extinction and succeeded as the first American wildlife reintroduction program.

- Also housed at the Denver Public Library, the papers of key women conservationists, such as Rosalie Edge and Velma “Wild Horse Annie” Johnston. Edge formed the Emergency Conservation Committee to establish Hawk Mountain Sanctuary (the first preserve for birds of prey), clashed with the Audubon Society over its policy of protecting songbirds at the expense of predatory species, and was a leading advocate for establishing the Olympic and Kings Canyon national parks. Johnston worked to end the capture and killing of wild mustang horses and free-roaming donkeys and lobbied to protect all wild equine species.

- Documents held at various institutions of the “father of forestry” Joseph Trimble Rothrock, who served as the first president and founder of the Pennsylvania Forestry Association and Pennsylvania’s first forestry commissioner. Rothrock’s work acquiring land for state parks and forests illustrates the role of key actors at state and regional levels.

- Project histories and reports of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation from the National Archives and Records Administration, chronicling the bureau’s work on projects including Belle Fourche, South Dakota; Grand Valley, Colorado; Klamath, Oregon; Lower Yellowstone, Montana; Shoshoni, Wyoming; and more.

- Select gray literature on conservation and environmental policy from the Institute of Governmental Studies Library at the University of California at Berkeley. This vast array of documents issued by state, regional, and municipal agencies; advocacy organizations; study groups; and commissions from the 1920s into the 1970s cover wildlife management, land use and preservation, public health, air and water quality, energy development, and sanitation.

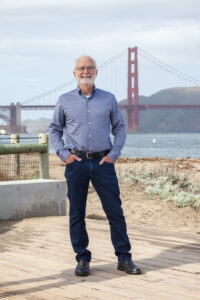

New Oral History from the OHC – Greg Moore: Executive Director of the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy

The San Francisco Bay Area is known for the kind of environmental advocacy that has become a model for regions around the country. There’s a long legacy, spanning decades, of people behind this work. Greg Moore is one of these people. Greg has dedicated his career to conserving public lands and making parks accessible for all. He, too, has become a model, someone to whom people throughout the country – and world – look for guidance.

Greg served as the executive director of the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy from 1986 until his retirement in 2019. The GGNPC was founded in 1981 and its mission is to preserve the Golden Gate national parks, enhance the park visitor experience, and build a community dedicated to conserving the parks for the future. But his work in the environmental sector began long before 1986, dating back to his time as a student at UC Berkeley in the newly-formed Conservation of Natural Resources School and College of Environmental Design, during the environmental decade of the 1970s when the Environmental Protection Agency was formed and regulatory laws, like the Clean Water Act, were passed. And even before that, when he was a ranger with the National Park Service.

I had the privilege of sitting down with Greg in 2022 to interview him about his life and work. In preparation for the sixteen hours I would end up spending with him, I spoke with a number of people who know him in different capacities – former fellow National Park Service rangers; as well as Conservancy board members, employees, and donors. One thing was clear: Greg is universally respected for his work and his collegiality. I kept hearing about how, as both a colleague and manager, he listened to people and carefully considered their perspectives. About how, as the executive director of the Conservancy, he wrote heartfelt letters to board members each year, letters that they all not only save, but cherish. About how he would write and perform in an annual musical parodying popular songs for year-end parties.

But what struck me the most was how present Greg was during each phase of our interview sessions. Whether we were discussing how he developed a love for music as a child; his studies at Cal and then later at the University of Washington; meeting his wife, Nancy, and raising their son; or his love for parks; the development of his career; managing a large staff and multi-million dollar fundraising campaigns; and working to make parks accessible for all, Greg took every question I asked seriously, responding sincerely and weaving in humor throughout.

Greg is perhaps best known for his work with the Conservancy. He played a role in the creation of the organization, which he discussed in more detail in his oral history, before becoming the executive director. There are an incredible array of projects on which he worked during his tenure with the Conservancy, like various habitat restorations, converting the Presidio from an Army base to a park, transiting Fort Baker from a military base into a national park, promoting citizen science through the Golden Gate Raptor Observatory, transforming Crissy Field into one of San Francisco’s crown jewels and creating the beloved Crissy Field Visitor Center, developing community partnerships and youth programs, and shepherding the Tunnel Tops project into existence. The list goes on.

The underlying theme of each of these projects was the drive to make parks accessible for everyone. “Parks for All” is the beating heart of the Conservancy’s mission. Here’s what Greg said about the origin of the mission:

“The ‘Parks For All’ came when the Conservancy was trying to think through how to simply and straightforwardly describe our mission. The Conservancy had a mission statement, but like many it was probably twenty-five to thirty words long, and I began thinking about how to put that in simple words that were very direct and, in some way, have the power-of-three impact. That’s when I began thinking, Well, of course, we’re about ‘parks.’ These are the physical places that we need to transform and enhance. Then we’re about ‘for all’ because these places are owned by every person in the United States as national parks, and then our final responsibility is ‘forever’ – to pass them from one generation to the next. It not only summarized our mission but almost described a theory of change that first you have the places and to make them for all youth to improve and enhance them. You have an opportunity to engage people in their enjoyment, in their stewardship, in their contributions for all, and then finally all the restoration work that cares for these places that you’ve enhanced and taken care of.”

Greg wanted to make sure people were aware that the parks existed, they felt comfortable there, and that they were relevant to the visitor’s life experience. He did this by bringing communities into planning conversations, implementing a bus route that would drive people from their neighborhoods to the parks and then back again, partnering with public libraries, and creating a multitude of programs – for kids, related to art, and citizen science for civilian park goers. Greg’s commitment to the Conservancy’s simple mission is what made the organization so successful and such an integral part of life in the Bay Area. And Greg’s interest in working with communities and listening to people – his colleagues, board members, donors, and park users alike – is what has made him such a towering figure in the Bay Area’s environmental movement.

It is with great excitement that we announce Greg Moore’s oral history is now publicly available.

Primary Sources: Environmental History: Conservation and Public Policy in America, 1870-1980

Environmental History: Conservation and Public Policy in America, 1870-1980 is a digital archive from Gale that provides access to sources documenting the emergence of conservation movements and the rise of environmental public policy in North America from the late 19th to the late 20th century.

The archive offers an incisive view into the efforts of individuals, organizations, and government agencies that shaped modern conservation policy and legislation. It includes:

- Papers of early environmentalists like George Bird Grinnell, a founding member of the Boone and Crockett Club and the first Audubon Society, and Joseph Trimble Rothrock, known as the “father of forestry.”

- Records of the American Bison Society, which helped save the American bison from extinction, and papers of women conservationists like Rosalie Edge and Velma “Wild Horse Annie” Johnston.

- Documents from the U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, and various state and municipal agencies focused on conservation and land-use matters.

- Grey literature from advocacy organizations, study groups, and commissions covering wildlife management, land preservation, public health, energy development, and more.

This archive provides valuable context for understanding today’s environmental challenges by chronicling the historical struggle to balance economic exploitation and resource conservation. It offers insights into the grassroots movements, advocacy efforts, and policy decisions that laid the foundation for modern environmental protection.

The resource includes grey literature on conservation and environmental policy from UC Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies Library.

Track changes: how BART altered Bay Area politics

By William Cooke

“It was just hooted at, the idea that you’d ever get people out of the automobile. They’d never come to San Francisco if they couldn’t drive into San Francisco.” — Mary Ellen Leary, journalist

“The formation of BART is actually one of the funniest things that ever transpired.”

— George Christopher, Mayor of San Francisco

On September 11, 1972, an estimated 15,000 people rode Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) on its very first day of operation. The train system, which at that time was a fraction of its current size, has been a vital service to Bay Area commuters for 50 years now. Those with an interest in the history of the Bay Area’s rapid transit system, or regional planning and public transportation more generally, will find a treasure trove of information in the UC Berkeley Oral History Center’s (OHC) archive.

But BART’s development is much more than a history of a public planning project. It is also a history of the evolution of government and of local versus regional power sharing. The OHC houses oral histories from big and small players in California’s public administration throughout the entire 20th century. The voices of politicians, journalists, city planners, and others reveal that BART’s development brought about a whole slew of questions regarding the proper role of government at all levels and required a great deal of reciprocity.

Mary Ellen Leary, a journalist who got her start with San Francisco News, studied and wrote extensively about urban planning and development in the early 1950s. In her oral history “A Journalist’s Perspective: Government and Politics in California,” she speaks at length about the origins of BART, and the broader development of regional agencies designed to meet the transportation needs of suburban areas, not just cities. “I felt then and still feel that the degree of local participation generated for BART from the first planning funds to the final bond issue was an extremely interesting and important political development.”

Leary says the impetus to begin work on a regional transit system originated in concerns about traffic congestion in the Bay Area. At the time, however, the idea of an alternative to driving in San Francisco seemed absurd. After all, BART would become the first new regional transit system built in the U.S. in 65 years.

But this worry about compact little San Francisco and the automobile launched this idea about rapid transit. And I laugh now about everybody giving BART such a hard time. It was just hooted at, the idea that you’d ever get people out of the automobile. They’d never come to San Francisco if they couldn’t drive into San Francisco.

According to Leary, local businessman Cyril Magnin and San Francisco Supervisor Marvin Lewis were among the first to consider the benefits of investing in a public transit system instead of parking garages. Unlike Los Angeles, the Bay Area could not build enough parking lots and garages to meet the needs of a car-reliant city due to limited space. Leary observes:

At any rate, they got a group of some business people to take seriously the idea of “How is San Francisco going to endure the flood of traffic that’s already coming in from the Golden Gate Bridge and the Bay Bridge? We can’t possibly do it.” The figures were coming out about what percentage of downtown Los Angeles was given over to automobile parking, most of it on the surface. They hadn’t yet begun many multiple-level parking facilities.

Eventually three counties — San Francisco, Alameda, and Contra Costa — committed to the transit system and developed the “BART Composite Report.” This had to be approved by their respective county supervisors in order for a bond measure to be placed on the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District-wide ballot in November of 1962.

In his oral history, longtime Republican politician and former Mayor of San Francisco from 1956–1964, George Christopher, remembers seeking the crucial aye vote of the fifth and still undecided Contra Costa County supervisor, Joe Silva. Silva had been under pressure from his constituents to vote no, because they would not directly benefit from the commuter rail but would bear the high price tag. Without Silva’s vote, the eventual passage of the measure in November and the $792 million bond issue may have been set back by years. According to Christopher, “The formation of BART is actually one of the funniest things that ever transpired,” involving a pre-dawn meeting and donuts.

I called him and I said “Supervisor, you’re the important man here. Now what are we going to do about this? All I’m asking is that you put it on the ballot and let the people decide whether they want it or not…. I said, “What time shall we meet?” He said, “Five o’clock in the morning.”… Sure enough we got up at four o’clock in the morning and we went over to Contra Costa County and finally found this restaurant. It turned out to be a little donut shop with no tables, no tables whatever, and we all sat around the counter. Here were all the teamsters, the truck drivers listening to every word we had to say…. I don’t know how many donuts we had, but we certainly filled ourselves.

Many hours and donuts later, Christopher had earned Silva’s crucial “yes” vote in support of the regional rail system. Christopher’s oral history is part of the Oral History Center’s “Goodwin Knight-Edmund G. ‘Pat’ Brown, Sr. Oral History Series,” which covers the California Governor’s office from 1953 to 1966, and is a gold-mine of fascinating anecdotes on city planning and transportation issues during that crucial decade.

Even before the bond issue was put on the ballot and approved in 1962, a consequential battle for regional power over transportation, including BART, was fought, ultimately resulting in a victory for local influence in this regional system. This battle was reflected in the approximately three-year long struggle between the Golden Gate Authority (GGA) and its younger competitor, the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG), for control over the planning and operation of transportation infrastructure in the region. Several oral histories from the Oral History Center discuss the importance of ABAG, which refers to itself as “part regional planning agency and part local government service provider.” In the oral history titled “Author, Editor, and Consultant: A Participant from the Institute of Governmental Studies,” Stanley Scott, a research political scientist at UC Berkeley, explains:

It came more from the large business interests, the Bay Area Council, with Edgar Kaiser being the chief proponent and front man, I guess you’d say, to create a Golden Gate Authority. That would incorporate the ports, the airports, and the bridges, the bridges being brought in essentially because they were very profitable organizations. So that one kind of came in, you might say, from the side, but at the same time, also involving regional restructuring.

This really upset the cities and counties, and quite a few others. A lot of people were concerned about it. A lot of people were concerned about just latching on to the bridges and tying them in with the airports and seaports. What are we going to do about all the other transportation problems? There was a great deal of concern.

It also exercised cities and counties that just did not want a major authority coming in from off the wall, so to speak. They began organizing themselves, and that was, in part, the genesis of ABAG. It was not the only reason for ABAG’s creation, but it provided substantial push in that direction. It had a lot to do with it. It scared the local people. That would have been in ’58, ’59, and ’60, that the Golden Gate Authority idea was kicked around. It was over a period of at least two years, and it could have been three, before it finally bit the dust.

T.J. Kent also addresses this theme about local influence and power sharing — with a focus on the role of ABAG — in his oral history, “Professor and Political Activist: A Career in City and Regional Planning in the San Francisco Bay Area.” Kent was a prominent city planner under San Francisco Mayor Roger Lapham in the 1940s, a deputy mayor for development under Mayor John Shelley in the 1960s, served on the Berkeley city council in the 1950s, and was a founder of UC Berkeley’s Department of City and Regional Planning.

According to Kent, former Mayor George Christopher opted to keep San Francisco out of ABAG because he felt that San Francisco was too important a player in the region to enter into an equal-representation regional government. His successor, Mayor John F. Shelley, reversed that policy, bridging the way to cooperation between the Bay Area’s largest city and the influential agency.

Shelley, with the board of supes [supervisors] backing him, he brought San Francisco into ABAG and appointed me as his deputy on the ABAG executive committee. I also served as the mayor’s deputy on the ABAG committee on goals and organization….The Committee prepared the regional home rule bill that was adopted by ABAG in 1966… It called for a limited function, directly elected, metropolitan government. That’s the key report.

Indeed, the publication of the Regional Home Rule and Government of the Bay Area report marked a huge milestone in the actualization of BART. ABAG, which was granted the authority by the State of California in 1966 to receive federal grants, included BART in the four elements of its metropolitan plan. Kent explains:

The first is the central district, enlarged and unified and focused in San Francisco; the second is a regional, peak-hour commuter transit system, which is BART and AC transit, plus the other transit systems serving San Mateo County, San Francisco and Marin and Sonoma counties; third is the open space system, to keep things from sprawling and for basic environmental reasons; and the fourth was comprised of the region’s residential communities, which shouldn’t get too dense, too overbuilt.

ABAG’s ability to receive and use federal money would prove vital to BART’s construction and continued operation. Furthermore, city and county representation on ABAG’s board — as opposed to zero locally elected officials in the defunct Golden Gate Authority — meant that cities likely had more of a say in the planning of BART than they would have had under the administration of the GGA.

Kent, then a Berkeley city councilmember, helped write the ABAG bylaws that balanced regional and local power. Kent believed in the importance of assigning enough power to regional agencies and districts like ABAG and BART, while also maintaining local autonomy. According to Kent — who throughout his oral history stresses the need to protect home rule wherever possible — counties that opted to stay in the Bay Area Rapid Transit District sometimes felt that the District was too restrictive or overbearing. But as a regional representative government with limited authority, conflicts were eventually solved. Kent remembers the back-and-forth between BART and Berkeley prior to the bond issue passing in 1962.

But those [counties] that were left in [the District], there were major battles in the BART legislation because the BART legislation had to give that agency that power and right. I was on the Berkeley council at the time and the battles were serious. There were many things that BART was required to do in consulting the cities and counties before the bond issue was proposed and voted on in 1962 and even after, which I think was good. They required BART to deal with Berkeley as an equal when Berkeley said, “We think—.” Berkeley got tremendous concessions from BART before the bond issue. You may not realize it, but the initial 1956 BART plan for the Berkeley line had it elevated all the way through downtown. Berkeley fought back before the bond issue vote of ʼ62 and got the middle third put underground.

Those counties that decided to stay in the District and cooperate with BART during its construction had a say in the decision-making process. Perhaps due to that fact, the 1962 district-wide bond issue surpassed the required 60% approval threshold, a result that came as a surprise to many political experts. Litigation and negotiations ensued with cities and counties across the Bay Area in the years that followed. But without the initial bond issue, BART could not have even begun construction.

Mary Leary observed that the impetus to create a regional, commuter rapid transit system — as well as the process of planning BART — did much to encourage local participation in politics. Even though ABAG was a regional entity with certain powers over local governments, Leary says that the agency allowed local governments a say in BART’s planning.

I think it was not unrelated that during this same era of local sharing in BART plans on a regional basis the Supervisors Association and the League of California Cities together launched ABAG, Association of Bay Area Governments, a voluntary group of cities and counties to discuss regional problems. It did not become a real regional government. In fact, I always felt it was created by those two groups to thwart moves towards regional government and to make sure cities and counties maintained their own strong voices. But it has been a significant forum and I think cooperation of the various governments around the Bay in planning BART gave it a good start. Interestingly, when planning got underway for where BART’s lines should run and stations should be, this became the first regional planning ever undertaken and local communities could see as some did that they were planning a sewer outfall just where the next-door neighbor town was planning a beach resort, that sort of thing.

In her oral history, Leary also noted a change in public perspective about public transit — away from the idea that no one would visit San Francisco if they couldn’t drive, to voters actually rejecting federal funds for a freeway connecting the Golden Gate and Bay bridges — and the relationship of BART to that.

Anyway, there was a good deal of political pride in the area that they had shared in developing BART from the very start, and it was part of the system’s success. Most other cities sat back and waited for Washington to provide funds for transit. Los Angeles never could get that much regional support. Of course, about that same time San Francisco was so supportive of the transit idea it rejected federal money for a freeway connection between the Golden Gate Bridge and the Bay Bridge. That really stirred a lot of national attention, saying “no” to millions or maybe billions.

Those interested in exploring the history of BART further, or learning more about the central themes of its history — local and regional government power sharing in the Bay Area, effective organization of regional governing bodies, and local participation in city planning, to name a few — can find much more in OHC’s numerous projects and individual interviews. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria from the OHC home page.

William Cooke is a fourth-year undergraduate student majoring in Political Science and minoring in History. In addition to working as a student editor for the Oral History Center, he is a reporter in the Sports department at UC Berkeley’s independent student newspaper, The Daily Californian.

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library has interviews on just about every topic imaginable. You can find the interviews mentioned here and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. We preserve voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page.

Related Oral History Center Projects

Covering the years 1953 to 1966, the Oral History Center (then the Regional Oral History Office) began the Goodwin Knight-Edmund G.Brown, Sr., Oral History Series of the State Government History Project in 1969. It covers the California Governor’s office from 1953 to 1966 and contains 84 interviews with a diverse set of personalities involved in Californian public administration. Topics include but are not limited to the rise and decline of the Democratic party, the impact of the California Water Plan, environmental concerns, and the growth of federal programs. This series includes the multivolume “San Francisco Republicans,” which includes the oral history of George Christopher, “Mayor of San Francisco and Republican Party Candidate.”

The San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge Oral History Project, launched in May of 2012, is a collection of 15 interviews that cover the construction of the Bay Bridge, maintenance issues, and the symbolic significance of the bridge in the decades after its construction. The majority of interviewees in this project spent their careers working on or around the bridge as architects, painters, toll-takers, engineers and managers, to name a few.

The California Coastal Commission Project traces the development of the only California commission voted into existence by the will of the people, from the campaign for Proposition 20 that created the agency in 1972 to the various development battles it confronted in the decades that followed. These interviews document nearly a half century of coastal regulation in California, and in the process, shed new light on the many facets involved in environmental policy.

Listen to the “Saving Lighthouse Point,” podcast, a collaboration between the OHC and the Bill Lane Center for the American West at Stanford University. “Saving Lighthouse Point” tracks the successful effort by citizens of Santa Cruz, with the support of the California Coastal Commission, to block the development of a bustling tourist and business hub on one of the last open parcels of land in the city.

Related Resources from The Bancroft Library

City and regional planning for the Metropolitan San Francisco Bay area, Kent, T. J., 1963. Bancroft Library/University Archives, Bancroft ; F868.S156K42

Open space for the San Francisco Bay area; organizing to guide metropolitan growth, Kent, T. J., 1970. University of California, Berkeley. Institute of Governmental Studies. Bancroft Library/University Archives. Bancroft ; F868.S156.57.K4

Regional plan, 1970–1990 – San Francisco Bay region, Association of Bay Area Governments, 1970. Bancroft Library/University Archives. Bancroft Pamphlet Double Folio ; pff F868.S156.8 A82

The BART experience: what have we learned? Webber, Melvin M.; University of California, Berkeley. Institute of Transportation Studies. 1976. Bancroft Library/University Archives. UC Archives ; 308m r42 W372 b

Summer Listening

The Oral History Center Director’s Column, June 2022

By Paul Burnett

Interim Director, Oral History Center

For many of us, summer brings the promise of vacation, or at least time off with friends and family to rest, celebrate, or explore the great outdoors.

Whether spending time in parks fits into your summer plans or not, you owe it to yourself to check out the Oral History Center’s new project on the history of Save Mount Diablo, and especially the accompanying podcast. Shanna Farrell, Amanda Tewes, and student research apprentices Anjali George and Andrew Deakin did an amazing job of telling the story of fifty years of this important land conservation organization in the Bay Area and Northern California. The three episodes span key aspects of its history, which involved grassroots organizing; drawing on youthful energy and the expertise from older, larger environmental groups such as the Save the Redwoods League; management of invasive species; competition with developers for land; reintroduction of endangered species; the role of artists in the movement; and the potential fate of the area as the organization battles climate change.

For more interviews on the history of parks and environmental movements, check out the projects on the East Bay Regional Park District, natural resources, and the Sierra Club.

As you are listening to the podcast, we hope you’re lucky enough to get some time to visit some green space near you and appreciate the wonders all around us.

One of the things we’ve also been doing this summer is moving house to a brand new website. However, there are currently no automatic redirects from our old site, so please bookmark our new home page. It will take a while for this new site to come up in search engines, so that will be the best way to reach our great content for now. You can go directly to our blog here.

And as this summer and recent events turn our attention both to sports and women’s rights, one of our student editors William Cooke has written a piece on the 50th anniversary of Title IX, the landmark law that prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex at schools that receive federal funds, and its impact on athletics at UC Berkeley.

Stay tuned for our next newsletter in August!

Happy summer!

Paul

The Berkeley Remix Season 7, Episode 3: “Save Mount Diablo’s Future”

In Episode 3, we explore Save Mount Diablo’s future. From addressing the challenges of COVID-19 to fundraising efforts to protecting land and biodiversity in the entire Diablo Range to mitigating the impacts of climate change to expanding membership and partnerships, Save Mount Diablo still has a lot of good work ahead. This episode asks: what challenges does Save Mount Diablo face today? What can Save Mount Diablo do about climate change? What does the future of Save Mount Diablo look like?

In season 7 of The Berkeley Remix, a podcast of the Oral History Center at UC Berkeley, we head to Mount Diablo in Contra Costa County. In the three-part series, “Fifty Years of Save Mount Diablo,” we look at land conservation in the East Bay through the lens of Save Mount Diablo, a local grassroots organization. It’s been doing this work since December 1971—that’s fifty years. This season focuses on the organization’s past, present, and future. Join us as we celebrate this anniversary and the impact that Save Mount Diablo has had on land conservation in the Bay Area and beyond.

This season features interview clips from the Save Mount Diablo Oral History Project. A special thanks to Save Mount Diablo for supporting this project!

LISTEN TO EPISODE 3 ON SOUNDCLOUD:

PODCAST SHOW NOTES:

This episode features interviews from our Save Mount Diablo Oral History Project and includes clips from: Seth Adams, Burt Bassler, Ted Clement, Bob Doyle, Abby Fateman, Jim Felton, John Gallagher, Scott Hein, and Egon Pedersen. To learn more about these interviews, visit the Oral History Center’s website.

This episode was produced by Shanna Farrell and Amanda Tewes, and edited by Shanna Farrell. Thanks to Andrew Deakin and Anjali George for production assistance.

Original music by Paul Burnett.

Album image North Peak from Clayton Ranch. Episode 3 image Mount Diablo Sunrise from Marin County. All photographs courtesy of Scott Hein. For more information about these images, visit Hein Natural History Photography.

PODCAST TRANSCRIPT:

Amanda Tewes: EPISODE 3: Save Mount Diablo’s Future

[Theme music]

Shanna Farrell: Welcome to The Berkeley Remix, a podcast from the Oral History Center at the University of California, Berkeley. You’re listening to our seventh season, “Fifty Years of Save Mount Diablo.”

Farrell: I’m Shanna Farrell.

Tewes: And I’m Amanda Tewes. We’re interviewers at the Center and the leads for the Save Mount Diablo Oral History Project.

Tewes: This season we’re heading east of San Francisco to Mount Diablo in Contra Costa County. In this three-part mini-series, we look at land conservation through the lens of Save Mount Diablo, a local grassroots organization.

Farrell: It’s been doing this work since December 1971—that’s fifty years. This season focuses on the organization’s past, present, and future. Join us as we celebrate this anniversary and the impact that Save Mount Diablo has had on land conservation in the Bay Area and beyond.

Farrell: In this episode, we explore the future of Save Mount Diablo.

Farrell: ACT 1: What challenges does Save Mount Diablo face today?

[Soundbed- ambulance]

Tewes: On March 16, 2020, counties across the Bay Area issued a shelter-in-place order because the COVID-19 pandemic was on the rise. While this impacted life for everyone, it interrupted the work that Save Mount Diablo was doing as people stayed at home and the future was uncertain.

[Soundbed- doors locking]

Tewes: But executive director Ted Clement knew that life wouldn’t stop, and people needed to know that they weren’t alone, perhaps more than ever. So he decided to light the beacon at the top of Mount Diablo. Think of a lighthouse shining on the top of the highest mountain in the Bay Area.

Ted Clement: We started a special program lighting the beacon every Sunday night and letting it shine until Monday morning, to really create that symbol of hope and gratitude for nature, as well as all of our first responders.

Farrell: The beacon was originally lit in 1928 by Charles Lindbergh to provide light to aviators in the early days of commercial flight. The beacon beamed every night until December 8, 1941, the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor. It was lit sporadically until it was restored in 2013, ensuring that it could shine for many years to come.

John Gallagher: I’m the one that lights the beacon. [laughs]

Tewes: That’s longtime Save Mount Diablo supporter John Gallagher. He helped light it every Sunday during the first year of the pandemic. He remembers the first time he did this, with help from Ted.

Gallagher: [laughs] The two of us drove up and turned it on. [laughs] And then of course, again, everybody is so paranoid about meeting together. You know, Ted and I are wearing masks and think, Should we really be standing up in that confined space at the beacon, you know, unprotected? Nobody knew.

Clement: They really stood out in those dark days. And we did that beacon lighting, kept that up for an entire year. We did it from April 2020 to April 2021.

[Soundbed- fire]

Farrell: And as people stayed inside during the early days of COVID, they started to value their outdoor spaces even more. This feeling intensified on September 9, 2020, when the sky stayed an eerie orange all day as wildfires burned across the Bay Area and smoke filled the air. As these fires further forced people inside, many began to think about the environment and care more about the future of the planet.

Clement: It’s a silver lining amidst the pandemic. I think so many people have discovered nature, because there weren’t many places they could go, so many places were shut down. Nature is a better option.

Tewes: Ted’s right. As Bay Area residents were spending a lot more time outside, they began to consider financially supporting organizations dedicated to preserving nature, like Save Mount Diablo. These donations kept Save Mount Diablo alive during this precarious time. Here’s board member Scott Hein.

[Soundbed- nature noises]

Scott Hein: We actually had some of our best fundraising campaigns ever during the pandemic, if you can believe it. And I think a big part of that was people wanting to contribute to something positive during those dark times. But I also think there was an increased appreciation of the work we do, and how important parks are and how they helped so many people endure the pandemic.

Farrell: Save Mount Diablo has always had the goal of conserving land, which includes buying more property. And even before the financial uncertainties of the pandemic, fundraising was a key effort. One of its ongoing projects was the Forever Wild Capital Campaign, which started around 2012 with the goal of raising money for land acquisition. This wrapped up in 2021. This campaign was so successful that it raised money for other program areas, like legal funds and stewardship.

[Soundbed- cash register]

Clement: We completed Forever Wild, this $15 million capital campaign, and it’s the largest, most consequential fundraising campaign in our organization’s history. And the campaign made a tangible, lasting difference, not only for our organization, but the whole Mount Diablo area. We conserved nine important properties; those will now be permanently protected and continue to benefit our area.

Tewes: All this sets up Save Mount Diablo to think about the next fifty years. Land conservation director Seth Adams’s big goal is to protect the entire Diablo Range. This is a huge undertaking because the range is 180 miles long and 20 miles wide. But of course, this effort requires money. Here’s Seth speaking about this work.

Seth Adams: Mount Diablo State Park—20,000 acres—has 10 percent of the state’s native plants. Over and over again down the Diablo Range, small areas have incredible biodiversity, species we haven’t even discovered yet. Because so much of it has been locked away in private hands since the Spanish got here that it’s intact, it’s unexplored, it’s unknown, and so a big part of what we’re doing is making it known. [laughs] And that level of intactness, that level of biodiversity, it’s one of the two or three hotspots for the entire state.

[Soundbed- nature noises]

Farrell: Protecting these lands, and the biodiversity that exists within them, is increasingly important as the climate warms and the pressures of development creep in. If Save Mount Diablo is able to protect the entire range, it can connect precious habitat corridors.

Adams: Rather than thinking about parks as islands where you go to see some relic of what was there before, the cities need to be the island surrounded by protected lands for basic ecosystem functions and beautiful views and proximity to open space and things like that. Rather than a park here or there, we need to connect all of the parks across the entire statewide, landscape-level distances.

Tewes: Expanding the organization’s mission to protect the entire Diablo Range has real impacts for the future of California. If Save Mount Diablo can realize Seth’s vision of cities as islands instead of having parks here and there, it will mitigate the impacts of climate change and development. More land protected means less traffic, cleaner air, and fewer threatened species. Longtime supporter and early board president Egon Pedersen agrees.

Egon Pedersen: I think it’s wonderful that they carry on Mary Bowerman’s goal to preserve the mountain and expand open space. I really admire them expanding beyond Mount Diablo, also. This is also open space for wildlife, so the more wildlife areas you can connect together, the more beautiful chance we have for survival of all the wildlife—plants and animals. So I think that’s beautiful.

Farrell: Here’s Seth again.

Adams: The things that were achievable were just the background noise. The bigger picture stuff is when you start thinking about policies and funding measures and new programs and expansions and things that you haven’t done before.

[Theme music]

Farrell: ACT 2: What can Save Mount Diablo do about climate change?

Gallagher: One year, there was a fire. I’m not sure where it was nor what year it was, but I could see the glow of the fire, and that’s a little disconcerting. It’s kind of hard to sleep when you can see the glow of a fire, even though it might be five miles away and there’s really nothing to worry about whatsoever. That was a little eerie.

Tewes: That was John Gallagher again talking about spending the night on the mountain before Save Mount Diablo’s annual Moonlight on the Mountain event. Each year, he’d sleep in the back of his pickup truck before the fundraiser.

[Soundbed- truck engine]

Farrell: John had a front-row seat to one of these fires, but many of the people who live in the towns surrounding Mount Diablo have to prepare for fire season each year. They keep a go-bag at the ready, waiting to evacuate if a fire creeps too close. This means that climate change is on the minds of all those involved with Save Mount Diablo. Now its programs are designed with this crisis in mind.

[Soundbed- fire]

Bob Doyle: And now we go from fires to drought to the point where the heat is killing people. You know, you have these really big events—fires, droughts—but now you have the secondary impact, which is the smoke, people dying from heat. And now we’re going into the drought cycle that these reservoirs are not refilled; they’re already way, way, way low. So you know, my attitude is: Mother Nature’s pretty pissed.

[Soundbed- rainstorm]

Tewes: That’s Bob Doyle, one of the original six members of Save Mount Diablo, talking about the impact that fires have on life in the Bay Area. It’s also a concern for Abby Fateman, executive director of the East Contra Costa Habitat Conservancy. In California, wildfires are directly connected to rainfall.

Abby Fateman: Water is absolutely critical to what we’re looking at, and it’s being affected by drought. It’s not just drought, it’s the timing of the rain. So if we get all of our rain right at the beginning of the year, and then it doesn’t rain for the rest of the season, that’s a problem. Or if it doesn’t rain until March, and rains for like a month and a half, that’s a problem. So it’s not just how much rain, it’s when it arrives that we’re struggling with.

Farrell: As we feel the effects of climate change more acutely, Save Mount Diablo and its partners have started thinking critically about how to tailor their goals to fit into the future.

Fateman: So we need to adapt, right? We’re committed to managing these lands in perpetuity for the species, and I don’t think we have all the answers on how we do that as climate continues to change. And I don’t really know what the endpoint is. Trying to figure out how to manage the lands with any immediate emergency versus what is our long-range plan for what’s really going to happen.

Doyle: It’s going to be a tremendous sacrifice for everybody. So you’ve got to deal with it. [laughs] You’ve got to deal with it. You can argue over what, how, and when, but it is very much accelerated and it’s frightening. A hundred and fifteen degrees in Portland, Oregon; a hundred, you know, what, fourteen, fifteen in Canada?

Tewes: That’s Bob again. In response to the changing climate, Ted initiated a climate action plan for Save Mount Diablo.

Clement: We’re really, really excited about it, and it’s already having a big impact on us. For example, our largest fund, the Stewardship Endowment Fund, as it’s laid out in our Climate Action Plan, we’ve got it invested in a completely fossil-free portfolio. We are starting massive tree-planting programs.

Farrell: Seth values Ted’s leadership on this.

Adams: He understands nature is the cure, and land is the answer in a lot of cases. It’s deeply related to carbon and how we handle climate change positively or negatively. But you know, we’ve started thinking about that in a more nuanced way, and that led to the Climate Action Plan, doing things in a thoughtful way, with urgency.

[Soundbed- nature noises]

Farrell: Here’s Abby Fateman again.

Fateman: We’re spending more time advocating for funding for research on climate change. We are advocating for money on: how do we respond to drought, how do we respond to fire, how do we manage our lands? You know, we’re at the urban-wildland interface, we have an obligation to keep communities safe, as well as species safe.

Tewes: This all means that Save Mount Diablo—and its partners—have their work cut out for them for the next fifty years. Here’s longtime board member and treasurer Burt Bassler.

Burt Bassler: Yeah, I don’t, I don’t see us not being needed anymore. The threats to the environment are real, climate change is real. Land preservation, in a small way, is important to mitigate climate change. We’re not going to outlast our usefulness.

[Theme music]

Farrell: ACT 3: So what does the future of Save Mount Diablo look like?

Farrell: Looking to the future of Save Mount Diablo, the organization needs to expand its stakeholders, including the people who use the land. Ted thinks about this a lot.

Clement: Sometimes there’s a lot of conflict and tension between different outdoor user groups, maybe between the mountain bikers and the hikers, or the rock climbers and the birders, you know? To me it’s always a little comical when I see such passion and tension between these groups. I’m like, do you understand what’s going on in the world right now? [laughs] You know, this little spat with the mountain bikers or whatever, that’s small, small potatoes. We’ve got a climate crisis right now, or we’ve also got a mass species extinction event. We actually need to change our thinking. And clearly, you know, the people that recreate outdoors love nature, and they love it in different ways and they exercise in different ways, but clearly they love getting out there. So let’s put the judgment aside.

[Soundbed- bicycles]

Tewes: Save Mount Diablo doesn’t just want to expand the different groups that appreciate the mountain, it also needs new blood and fresh perspectives to continue the work. John Gallagher agrees.

Gallagher: As a board, we’re always talking about: how can we get some younger people on the board? You know, we’re all a bunch of old white guys, and so forth. Well, the fact is every organization talks about that.

Clement: And then diversify. We have got to invite more people into conservation. We’ve got to show respect to more types of communities, ethnic communities, different outdoor user groups. We need to embrace one another, recognize that we need more people engaged in taking care of nature, which we love. And let’s actually welcome more people into the tent, and get them on the team all working in the same direction.

Farrell: Women also need a seat at the table. Here’s Abby Fateman.

Fateman: You know, one of my concerns is: who is the next group of people, and it always surprises me who it is, right? I mean, I go to meetings and I’m the only woman in the room—still. I’m the youngest person in the room, and I’m not that young. But I wonder about that, and I worry about it.

Tewes: Bob Doyle first got involved with Save Mount Diablo when he was young. Now he’s focused on bringing in younger generations to keep the organization alive and rethink what’s possible.

Doyle: I think about that so much today with the issues of equity and inclusion and, you know, the whole social youth effort. They’re going to ask, “Why can’t we?” rather than, you know, “Why should we?”

Farrell: Like Bob, Ted also wants to bring younger generations into Save Mount Diablo’s work. Here’s Seth Adams speaking about that.

Adams: Ted’s got a real focus on youth and conservation collaborations with youth and youth education, and the solution to a lot of our problems has to lie with educating youth, and that leads in every direction, too.

Tewes: Involving younger activists and supporters is important because climate change will have a big impact on them. Here’s Save Mount Diablo board president Jim Felton discussing this.

Jim Felton: One major thing is that I’m trying to do my best for our community and for the future generations. This land use, it’s not necessarily my problem in my lifetime, it’s my kids’ problem and their kids’ problem, and are we going to have places that people want to go and be outdoors and enjoy the wilderness right here in the Bay Area?

Farrell: Bob knows from experience that this work is a lifelong commitment.

Doyle: It’s a long game, but other young people involved, when they ask me, I said, “This is a marathon, not a sprint.” I’m talking years, and that’s how you make progress. It takes a long time, but it’s amazing if you focus and have a commitment.

Tewes: Bob has seen this commitment pay off.

Doyle: One thing about the past is everybody was pessimistic. We weren’t going to save Mount Diablo; it was just so much growth, everybody wanted real estate development, nobody listened, like save Mount Diablo from what? And I think that story is a very positive, successful story. Don’t take the fun out of environmental activism. It gets sometimes too intense, too serious, and we always like to say, “Parks make life better.”

[Soundbed- nature noises]

Farrell: Here’s Jim Felton again.

Felton: As I said, I think the future is going to look different. We’re going to get more involved in the Diablo Range, we’re going to get more involved in education, we’re going to continue to be involved in some of the land-use issues in our geographical area.

Tewes: Ted is also optimistic about the future of Save Mount Diablo.

Clement: We’ll have more and more work to do in the next fifty years as we shore up the Diablo Range, make sure that Mount Diablo does not lose its connection. Yeah, there’s a lot of good conservation left to do.

Farrell: Even with fifty years of land conservation in the rearview mirror, Save Mount Diablo still has a lot of good work ahead.

[Theme music]

Farrell: Thanks for listening to “Fifty Years of Save Mount Diablo” and The Berkeley Remix, a podcast from the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. Founded in 1953, the Center records and preserves the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world. This episode was produced by Shanna Farrell and Amanda Tewes.

Tewes: This episode features interviews from our Save Mount Diablo Oral History Project and includes clips from: Seth Adams, Burt Bassler, Ted Clement, Bob Doyle, Abby Fateman, Jim Felton, John Gallagher, Scott Hein, and Egon Pedersen. A special thanks to Save Mount Diablo for supporting this project. Thank you to Andrew Deakin and Anjali George for production assistance. To learn more about these interviews, visit our website listed in the show notes. Thanks for listening and join us next time!

The Berkeley Remix Season 7, Episode 2: “Save Mount Diablo’s Present”

In Episode 2, we explore Save Mount Diablo’s present. From supporting ballot measures and fundraising efforts to cultivating relationships with nature enthusiasts and artists to collaborating with outside partners, Save Mount Diablo continues to “punch above its weight.” This episode asks: now that Save Mount Diablo has conserved the land, how does it take care of it? How does Save Mount Diablo continue to build a community? How are artists activists, and how do they help support Save Mount Diablo? How does Save Mount Diablo sustain partnerships to conserve land?

In season 7 of The Berkeley Remix, a podcast of the Oral History Center at UC Berkeley, we head to Mount Diablo in Contra Costa County. In the three-part series, “Fifty Years of Save Mount Diablo,” we look at land conservation in the East Bay through the lens of Save Mount Diablo, a local grassroots organization. It’s been doing this work since December 1971—that’s fifty years. This season focuses on the organization’s past, present, and future. Join us as we celebrate this anniversary and the impact that Save Mount Diablo has had on land conservation in the Bay Area and beyond.

This season features interview clips from the Save Mount Diablo Oral History Project. A special thanks to Save Mount Diablo for supporting this project!

LISTEN TO EPISODE 2 ON SOUNDCLOUD:

PODCAST SHOW NOTES:

This episode features interviews from our Save Mount Diablo Oral History Project and includes clips from: Seth Adams, Bob Doyle, Ted Clement, Abby Fateman, Jim Felton, John Gallagher, Scott Hein, John Kiefer, Shirley Nootbaar, Malcolm Sproul, and Jeanne Thomas. To learn more about these interviews, visit the Oral History Center’s website.

This episode was produced by Shanna Farrell and Amanda Tewes, and edited by Shanna Farrell. Thanks to Andrew Deakin and Anjali George for production assistance.

Original music by Paul Burnett.

Album image North Peak from Clayton Ranch. Episode 2 image Lime Ridge Open Space. All photographs courtesy of Scott Hein. For more information about these images, visit Hein Natural History Photography.

PODCAST TRANSCRIPT:

Amanda Tewes: EPISODE 2: Save Mount Diablo’s Present

[Theme music]

Shanna Farrell: Welcome to The Berkeley Remix, a podcast from the Oral History Center at the University of California, Berkeley. You’re listening to our seventh season, “Fifty Years of Save Mount Diablo.”

Farrell: I’m Shanna Farrell.

Tewes: And I’m Amanda Tewes. We’re interviewers at the Center and the leads for the Save Mount Diablo Oral History Project.

Tewes: This season we’re heading east of San Francisco to Mount Diablo in Contra Costa County. In this three-part mini-series, we look at land conservation through the lens of Save Mount Diablo, a local grassroots organization.

Farrell: It’s been doing this work since December 1971—that’s fifty years. This season focuses on the organization’s past, present, and future. Join us as we celebrate this anniversary and the impact that Save Mount Diablo has had on land conservation in the Bay Area and beyond.

Farrell: In this episode, we explore Save Mount Diablo’s present.

Tewes: ACT 1: Now that Save Mount Diablo has conserved the land, how does it take care of it?

[Soundbed- nature noises]

Tewes: As we heard in our last episode, Save Mount Diablo was successful in accomplishing its original goal of expanding the Mount Diablo State Park from 6,788 acres to 20,000. It was also able to protect 90,000 acres of land that surrounded the mountain. These dreams were hard fought. Now that the organization had saved this land, how did it care for it? As we know, at first it relied on volunteers and supporters. Some of the volunteers who wanted to help beyond giving money found their way to different committees, like Stewardship and Land Acquisition.

Jim Felton: When I first started, we used to get together maybe four times a year, all the stewards, and talk about the problems and things that needed fixing. And of course, I’d go to a site that wasn’t mine to watch and help with the fence or help with some problem that needed fixing. Near Curry Canyon, there’s another property out there where the culvert got full of trees, and we all just had to climb in there and pull them out.

Farrell: That’s Jim Felton, who was a member of the Stewardship Committee before becoming president of Save Mount Diablo’s board. Each member of the Stewardship Committee is responsible for maintaining a parcel of land.

Felton: Well, it was once a month to check it out. So most of the time it was checking things out, but then there were jobs to do. We found bamboo or Arundo it’s called, Arundo in the creek in our property, and we wanted to get it out of there because it tends to spread, and it’s a very invasive species. So I spent quite a few hours digging and using a pick just getting that out of the river, and it hasn’t come back.

[Soundbed- river rushing]

Tewes: Some of the land hadn’t been maintained in some time, so it required a fair amount of cleanup. John Gallagher got involved with Save Mount Diablo in the year 2000. He started on the Land Committee and then moved to the Stewardship Committee. Here he is talking about the work he put in to care for neglected properties.

John Gallagher: I can’t tell you the number of trailers full of old car tires that we had hauled off, for example. Piles of pipe, barbed wire, and so forth that we’ve hauled off to the recycle center or whatever.

[Soundbed- construction, truck hauling garbage]

Farrell: There was no cost to being involved with Save Mount Diablo in this way. Jim Felton remembers it was just “gas and time.”

Felton: For old guys, it was pretty messy projects, but no, no cost but just gas, but time, really, and a sore back.

Tewes: But there was joy in this hard work. John Gallagher says:

Gallagher: And of course it’s all outdoors. You know, we get to go places where other people don’t get to go, and I like that.

Farrell: As Save Mount Diablo moved beyond its original function as an advocate for land conservation, it realized it needed to build relationships with people who owned property near its land parcels. Here’s land conservation director Seth Adams.

Seth Adams: Well, the unusual thing about Save Mount Diablo is that we started as an advocacy organization and then added acquisition functions.

[Soundbed- door knocking]

Adams: If we buy a piece of property, we’re going to be in contact with the neighbors, and more likely than not, we’re going to protect land next door to that property because they get to know us, and they see that we’re upfront and responsible and do what we say we’re going to do and we’re nice and we’re not confrontational. And buying a property is always a gateway to the surrounding properties.

Tewes: These relationships mattered, especially when it came to land acquisition. Here’s board member and former president Scott Hein.

Scott Hein: The idea is to try to develop relationships with long-time landowners who may have property that you would like to acquire at some time, so that when they’re ready to sell they’ll think about you. You know, they might not give you a bargain, but at least they won’t be opposed to thinking about doing a deal with you, and so that’s the sort of general idea. And so it takes developing relationships and maintaining those relationships over time and communicating. It’s something you have to be proactive about. The landowners aren’t going to come and find you; in most cases, you have to go find them, and then figure out what kind of relationship they want to have.

Adams: When a landowner is going to sell their property, they typically want the highest value. There are some that are really enlightened, and they have come to you because they want to see their properties protected, and that’s growing, but it wasn’t the norm in the early years. There’s a lot of land-rich, cash-poor landowners around Mount Diablo.

Farrell: That was Seth again. The organization has to prioritize which properties it wants to acquire. Here’s Seth talking about how to consider those decisions.

Adams: Let’s say we know that our priority list has 180 properties on it, and we have a Landowner Outreach Subcommittee that meets monthly, and we go over to the top twenty of those priorities.

Tewes: The volunteers in the Land Committee still play a big role in acquiring land. Here’s John Gallagher again.

Gallagher: We keep a list about that and then try to decide if the cost of the property is worth it. Just as you and I might decide to buy a new couch or something like that, you just have to make that calculation. Well, I really like it, but is it worth it, do I need it that badly? And the Land Committee makes those decisions and recommendations. “Hey, listen, there’s a nice piece of property, but it’s totally surrounded by houses, and even though it adjoins a state park, it will never be a place for access or anything else, it would just be another parcel. If it’s really cheap, let’s go for it.” Or we say, “We need this one, this is something we’ve looked at, it’s been on our list for twenty-five years.”

Farrell: Here’s Seth again.

Adams: And then you wait for those times in people’s lives when they either put it up on the market or you know something is going to happen. This landowner’s husband died and so that’s a life change, which probably is going to result in opportunity. It’s the four D’s: death, divorce, disaster, disease, [laughs] and those are the times when conservation is most likely to happen.

Farrell: Jim Felton also explains that building relationships with neighbors is part of Save Mount Diablo’s stewardship model.

Felton: We’ve had events for neighbors, some of our sites, and barbecues and things. And some people really like Save Mount Diablo in the neighborhood and some people just don’t like them at all, and they were really nasty. It’s too bad because, I mean, what we’re doing is preventing somebody from building ten houses next door to them, but they didn’t like it. They saw it almost as government intrusion, that type of behavior.

Tewes: The organization knows how to strike when the iron is hot. In the late 2000s, during the recession, it saw an opportunity. John Gallagher remembers:

Gallagher: We didn’t have very many properties anyway, and then during the recession, we acquired a whole bunch of them, bang, bang, bang, bang. And they were often distressed properties that had junk on them or gates that didn’t work or fire abatement that wasn’t being done.

Farrell: Save Mount Diablo doesn’t just acquire new lands, it supports political action as a way to conserve open space. This means it also backs local ballot measures that limit growth of new development in Contra Costa County. Here’s Scott Hein.

Hein: Prior to the establishment of the urban limit line, there was a lot of speculative development going on around the County in all the cities in the County, and it was really difficult for Save Mount Diablo or anyone interested in protecting that land to get their hand around it.

[Soundbed- construction]

Tewes: Urban limit lines are important. They stop development from happening, which can in turn, protect plants and animals.

[Soundbed- bird noises]

Tewes: In 1990, County voters approved Measure C, the 65/35 Ordinance, which required at least 65 percent of land be preserved for agriculture, parks, and other open space. In 2006, Contra Costa County residents voted to extend this limit for up to another 30 years.

Farrell: As Save Mount Diablo got more involved with local politics, it became more visible. As a result, it drew more people to the organization.

[Theme music]

Farrell: ACT 2: How did Save Mount Diablo continue to build a community?

John Kiefer: I love the mountain, but in reality, it’s more accurate to say I love the people that love the mountain.

Tewes: That’s longtime Save Mount Diablo supporter John Kiefer. It takes a whole community to rally around the organization, and this includes those with varying interests in the natural space. One group that loves the mountain include those who support wildlife like falcons.

[Soundbed- peregrine falcons]

Farrell: The chemical DDT had been a commonly-used insecticide since the 1940s. It was sprayed all over, mainly to kill mosquitoes. But DDT caused a lot of damage, including around Mount Diablo. It destroyed bird populations because it thinned the eggshells of baby birds like peregrine falcons, killing them before they could hatch. By 1950, peregrines had disappeared from Mount Diablo. And in 1970, they were listed as an endangered species in California. DDT was nationally banned in 1972 after the publication of Silent Spring by Rachel Carson brought its dangers to light. That same year, there were only 2 nesting pairs of peregrine falcons left in the entire state of California.

[Soundbed- sad sounds of birds]

Tewes: Over a decade later, in 1989, peregrine falcons were reintroduced to Mount Diablo by wildlife biologist Gary A. Beeman. Seth Adams and Save Mount Diablo played a key role in this work by gathering volunteer supporters and helping to fund it. Here’s Shirley Nootbaar, who lives near the mountain and loves peregrines.

Shirley Nootbaar: [laughs] The Peregrines, you know, were first started back on the mountain back in the end of the eighties. They tried to encourage nesting. They would have prairie falcons incubate the vital eggs of peregrines that they had produced in probably zoos, and that was the way they finally got the wild peregrines to start in Pine Canyon, which is right near where I live.

Farrell: These falcons have an ardent group of supporters, including the Peregrine Team in Pine Canyon, which was founded in 2015. This is a natural history group that assists park rangers during nesting season. Thanks to its efforts, there are now about 400 pairs of peregrine falcons in California, which matches estimates from pre-DDT levels. Shirley is actively involved with this group.

Nootbaar: Last year, they did not produce any chicks. This year, they did, and it was exciting. The Peregrine Team was overjoyed. The pair of peregrines had four eggs that blossomed into chicks, and everybody was so excited, but a great horned owl came along and ate them.

[Soundbed- peregrine falcons]

Malcolm Sproul: Everybody loves peregrine falcons; you know, it’s a sexy, you know, dynamic bird.

Tewes: That was Malcolm Sproul, who works in environmental planning. He was also Save Mount Diablo’s board president when the organization started to participate in BioBlitz. BioBlitz is a day-long event where naturalists and citizen scientists inventory all species of plants and animals living in a designated area. Malcolm plays a big role in Save Mount Diablo’s BioBlitz.

Sproul: I’m a participant, a very willing participant. You go out to an identified area, and you’re trying to document as many species as you possibly can in a twenty-four-hour period. And my expertise is birds and mammals, you know, a little bit of plants. If I see something interesting, I can record it and tell people. But primarily, I’m out there because of wildlife, and it’s just fun to get out in the field. And it’s a chance to get together with other people with similar backgrounds and interests, and share that. Then the organization loves to use it as a way to say how valuable properties are.

[Soundbed- birds and frogs]

Farrell: During BioBlitz, the group often identifies over 700 species that live in the Diablo Range.

Sproul: To me, that’s the real value of it. It’s when you find something that you didn’t know was there, and you can find maybe why it’s there, but that’s a little piece of information that we didn’t have before.

Tewes: BioBlitz brings new people to the mountain. They also act as a gateway to another Save Mount Diablo educational event: Four Days Diablo. Here’s Scott Hein talking about this.

[Soundbed- gravel crunching, people walking through dirt]

Hein: So it’s, you know, thirty to forty miles, depending on the side trips we take. Three nights we hike entirely on public lands the whole way, except for in more recent years we’ve detoured onto our Curry Canyon Ranch Property, and we get permission to hike out through a private ranch on that day. You can hike from Walnut Creek to Brentwood and immerse people in the work that we and our partners have done for, you know, the last fifty years. There’s no better way to expose people to the work we do and the importance than getting them out on the land.

Tewes: John Gallagher says:

Gallagher: At the time, Seth was leading every hike, so he was able to brag and brag and brag about what Save Mount Diablo had done with this property and that property.

Sproul: We take people out for four days. They get spoiled—I mean, they have to hike. It’s hot sun and things like that, and you get blisters, and some people can’t make it. It’s some work. But it’s taking people out into the areas that have been protected, and showing them what they have helped protect.

Tewes: That was Malcolm Sproul.

[Soundbed- people walking]

Farrell: Indeed, this event also helps develop relationships with potential donors. Another event that brings these donors back to the land is Moonlight on the Mountain. This fundraising dinner every September takes place at an area called China Wall. And it takes effort to get out there.

Felton: So it’s on a flat mesa area on this ridge right next to what’s called China Wall, which is a geological formation that’s pretty unique, a lot of just outcroppings. We’d light that up with spotlights, so as the sun goes down, it is all beautifully lit, and the visuals are really amazing. And of course some years, you get the moon, some years, it doesn’t always work out that way.

Tewes: That’s Jim Felton. Here’s Scott Hein again.

Hein: So the idea with Moonlight on the Mountain is: bring 500 of our closest friends up onto the mountain and have a white tablecloth sit-down dinner, sitting outside, not under tents or anything like that, and have an evening of, you know, learning about the organization and making contributions and bidding on artwork and experiences and things like that. So it’s completely unique, right? I don’t know of any other events like it in the Bay Area, where you bring that many people outside in the environment, sitting in front of the mountain.

Tewes: This is a beloved event. It draws volunteer support from many. For instance, John Gallagher helps set up for the event. The night before, he sleeps in his truck on the mountain.

Gallagher: Once in a while, the cows will come around and stick their nose in my nose while I’m asleep, you know, in the bed of my truck.

[Soundbed- cow noise]

Gallagher: [laughs] And of course I hear the coyotes calling, which is always a delight. But you know, the wind comes up and the fog comes in or something like that, and it’s just nice and quiet and serene.

Farrell: While some of these events bring in money, they all build community around Save Mount Diablo. Another way the organization does this is through educational efforts. If you don’t know about the land, you can’t love it enough to preserve it. Here’s executive director Ted Clement talking about the program on Mangini Ranch Educational Preserve, where community groups and schools can explore the land.

Ted Clement: I started to hear more and more from teachers that were doing our Conservation Collaboration Agreement Program that it was powerful for the students. And they really liked that students were out on our properties having these intimate experiences in nature and there was no one else there, not like a state park with lots of outsiders and other people wandering around. The teachers said it just felt very safe and intimate. And we want to make it as easy as possible and as affordable as possible for all these different groups of people to get out there and have a really special, intimate experience in nature. It’s their property for the day.

[Theme music]

Tewes: ACT 3: How are artists activists, and how do they help support Save Mount Diablo?

[Soundbed- river flowing]

Tewes: Mount Diablo is a beautiful place, with its sprawling vistas and rolling hills, where grasslands give way to wooded areas. It’s been a source of inspiration over the years for many artists. And Save Mount Diablo has been lucky to attract a community of these artists, like Shirley Nootbaar, Scott Hein, Stephen Joseph, and Bob Walker, who care about the mountain enough to capture it in their paintings and photographs.

[Soundbed- camera clicking]

Tewes: These pieces illustrate the beauty of the range, and why it’s worth preserving.

Farrell: Shirley Nootbaar, who lives in Walnut Creek, started painting the mountain in the 1970s. She sees the landscape through an artist’s eyes.

Nootbaar: The trees are a rich green and right now the grasses are golden and the sky is blue, I mean those colors, green, kind of a raw umber or raw sienna kind of color, and the beautiful blue of the sky. So as far as the colors of painting the mountain, it kind of depends on what your mood or your idea at the time is, and it changes all the time.

Tewes: Shirley taught watercolor classes and brought her students to the mountain to paint what they saw. She also got involved with the Mount Diablo Interpretive Association.

Nootbaar: In 1983, I think it was, they were able to open up the museum at the top of the mountain after it was closed for a number of years. We formed an art committee through the Mount Diablo Interpretive Association, and the art committee created these various shows, probably four times a year, and hung work of the various people that would submit work, and it was different themes of either a particular area or maybe it was a high school group or whatever; could be photography, as well, of course. Yeah, I thought it was very successful.

Farrell: Photographs are also an important part of Save Mount Diablo’s advocacy. Scott Hein is a nature photographer and takes photos for the organization. Seth Adams even sends him out on assignment to photograph land around the mountain.

[Soundbed- more camera clicking]

Hein: Not all the lands we protect are easily accessible, and not every person has the time or the ability to get out on the land, and so photographs are the next best thing. They’re the way that we can communicate that beauty to people who can’t experience it in person, and conservation photography has been a critical tool going almost all the way back to the beginning of land conservation.

Tewes: Scott’s work has many admirers, like Shirley.

Nootbaar: Scott Hein in the Save Mount Diablo organization does a beautiful job with photographs.

Farrell: Before Scott was Bob Walker. Remember him from episode one?

Hein: Bob Walker was involved with the organization and doing nature photography and conservation photography from 1982 to 1992, when he passed away. He was a real environmental advocate, who was also a fantastic photographer. He was just relentless in photographing, and taking people out there to hike and learn about it.

Jeanne Thomas: His photography told a story. And the mountain, you looked down and could see development coming up and say, “Oh, if it weren’t for the park, the development wouldn’t stop.”

Tewes: That’s longtime volunteer and donor Jeanne Thomas. She also loves to take photographs on the mountain, including of local wildflowers. There’s a strong connection between Mount Diablo and these artists. Here’s Shirley Nootbaar again, talking about what the land has meant to her.

[Soundbed- bird and animal noises]

Nootbaar: I love where I live, I love to hear the birds, and I love the animals, and when I go up into the park, I’m always aware of that. I’m not a botanist, I’m not a biologist, I’m not a zoologist, I’m not a geologist, but I do appreciate all of those things. It’s much my therapy and my love.

[Theme music]

Farrell: ACT 4: How does Save Mount Diablo sustain partnerships to conserve land?

Farrell: From the beginning, Save Mount Diablo has been an organization that’s worked collaboratively with outside partners. This has become an even more important part of its model. The organization works with the California State Park system, as Mount Diablo is a state park. It also collaborates with the East Bay Regional Park District and the East Contra Costa Habitat Conservancy to accomplish its goals.

Tewes: In 1988, Save Mount Diablo original member Bob Doyle started working for the East Bay Regional Park District. Though he was working for the Park District, which was founded in 1934, he never forgot about his roots with Save Mount Diablo. Bob and Seth Adams worked together to pass a local bond measure that would provide funding to both entities. Here’s Bob discussing the impact of that measure and the longevity of that relationship.