Tag: Bay Area history

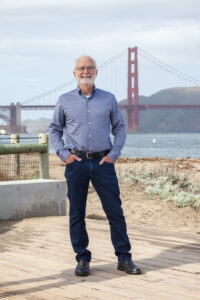

New Oral History from the OHC – Greg Moore: Executive Director of the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy

The San Francisco Bay Area is known for the kind of environmental advocacy that has become a model for regions around the country. There’s a long legacy, spanning decades, of people behind this work. Greg Moore is one of these people. Greg has dedicated his career to conserving public lands and making parks accessible for all. He, too, has become a model, someone to whom people throughout the country – and world – look for guidance.

Greg served as the executive director of the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy from 1986 until his retirement in 2019. The GGNPC was founded in 1981 and its mission is to preserve the Golden Gate national parks, enhance the park visitor experience, and build a community dedicated to conserving the parks for the future. But his work in the environmental sector began long before 1986, dating back to his time as a student at UC Berkeley in the newly-formed Conservation of Natural Resources School and College of Environmental Design, during the environmental decade of the 1970s when the Environmental Protection Agency was formed and regulatory laws, like the Clean Water Act, were passed. And even before that, when he was a ranger with the National Park Service.

I had the privilege of sitting down with Greg in 2022 to interview him about his life and work. In preparation for the sixteen hours I would end up spending with him, I spoke with a number of people who know him in different capacities – former fellow National Park Service rangers; as well as Conservancy board members, employees, and donors. One thing was clear: Greg is universally respected for his work and his collegiality. I kept hearing about how, as both a colleague and manager, he listened to people and carefully considered their perspectives. About how, as the executive director of the Conservancy, he wrote heartfelt letters to board members each year, letters that they all not only save, but cherish. About how he would write and perform in an annual musical parodying popular songs for year-end parties.

But what struck me the most was how present Greg was during each phase of our interview sessions. Whether we were discussing how he developed a love for music as a child; his studies at Cal and then later at the University of Washington; meeting his wife, Nancy, and raising their son; or his love for parks; the development of his career; managing a large staff and multi-million dollar fundraising campaigns; and working to make parks accessible for all, Greg took every question I asked seriously, responding sincerely and weaving in humor throughout.

Greg is perhaps best known for his work with the Conservancy. He played a role in the creation of the organization, which he discussed in more detail in his oral history, before becoming the executive director. There are an incredible array of projects on which he worked during his tenure with the Conservancy, like various habitat restorations, converting the Presidio from an Army base to a park, transiting Fort Baker from a military base into a national park, promoting citizen science through the Golden Gate Raptor Observatory, transforming Crissy Field into one of San Francisco’s crown jewels and creating the beloved Crissy Field Visitor Center, developing community partnerships and youth programs, and shepherding the Tunnel Tops project into existence. The list goes on.

The underlying theme of each of these projects was the drive to make parks accessible for everyone. “Parks for All” is the beating heart of the Conservancy’s mission. Here’s what Greg said about the origin of the mission:

“The ‘Parks For All’ came when the Conservancy was trying to think through how to simply and straightforwardly describe our mission. The Conservancy had a mission statement, but like many it was probably twenty-five to thirty words long, and I began thinking about how to put that in simple words that were very direct and, in some way, have the power-of-three impact. That’s when I began thinking, Well, of course, we’re about ‘parks.’ These are the physical places that we need to transform and enhance. Then we’re about ‘for all’ because these places are owned by every person in the United States as national parks, and then our final responsibility is ‘forever’ – to pass them from one generation to the next. It not only summarized our mission but almost described a theory of change that first you have the places and to make them for all youth to improve and enhance them. You have an opportunity to engage people in their enjoyment, in their stewardship, in their contributions for all, and then finally all the restoration work that cares for these places that you’ve enhanced and taken care of.”

Greg wanted to make sure people were aware that the parks existed, they felt comfortable there, and that they were relevant to the visitor’s life experience. He did this by bringing communities into planning conversations, implementing a bus route that would drive people from their neighborhoods to the parks and then back again, partnering with public libraries, and creating a multitude of programs – for kids, related to art, and citizen science for civilian park goers. Greg’s commitment to the Conservancy’s simple mission is what made the organization so successful and such an integral part of life in the Bay Area. And Greg’s interest in working with communities and listening to people – his colleagues, board members, donors, and park users alike – is what has made him such a towering figure in the Bay Area’s environmental movement.

It is with great excitement that we announce Greg Moore’s oral history is now publicly available.

Track changes: how BART altered Bay Area politics

By William Cooke

“It was just hooted at, the idea that you’d ever get people out of the automobile. They’d never come to San Francisco if they couldn’t drive into San Francisco.” — Mary Ellen Leary, journalist

“The formation of BART is actually one of the funniest things that ever transpired.”

— George Christopher, Mayor of San Francisco

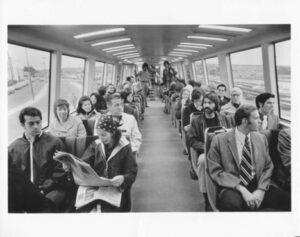

On September 11, 1972, an estimated 15,000 people rode Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) on its very first day of operation. The train system, which at that time was a fraction of its current size, has been a vital service to Bay Area commuters for 50 years now. Those with an interest in the history of the Bay Area’s rapid transit system, or regional planning and public transportation more generally, will find a treasure trove of information in the UC Berkeley Oral History Center’s (OHC) archive.

But BART’s development is much more than a history of a public planning project. It is also a history of the evolution of government and of local versus regional power sharing. The OHC houses oral histories from big and small players in California’s public administration throughout the entire 20th century. The voices of politicians, journalists, city planners, and others reveal that BART’s development brought about a whole slew of questions regarding the proper role of government at all levels and required a great deal of reciprocity.

Mary Ellen Leary, a journalist who got her start with San Francisco News, studied and wrote extensively about urban planning and development in the early 1950s. In her oral history “A Journalist’s Perspective: Government and Politics in California,” she speaks at length about the origins of BART, and the broader development of regional agencies designed to meet the transportation needs of suburban areas, not just cities. “I felt then and still feel that the degree of local participation generated for BART from the first planning funds to the final bond issue was an extremely interesting and important political development.”

Leary says the impetus to begin work on a regional transit system originated in concerns about traffic congestion in the Bay Area. At the time, however, the idea of an alternative to driving in San Francisco seemed absurd. After all, BART would become the first new regional transit system built in the U.S. in 65 years.

But this worry about compact little San Francisco and the automobile launched this idea about rapid transit. And I laugh now about everybody giving BART such a hard time. It was just hooted at, the idea that you’d ever get people out of the automobile. They’d never come to San Francisco if they couldn’t drive into San Francisco.

According to Leary, local businessman Cyril Magnin and San Francisco Supervisor Marvin Lewis were among the first to consider the benefits of investing in a public transit system instead of parking garages. Unlike Los Angeles, the Bay Area could not build enough parking lots and garages to meet the needs of a car-reliant city due to limited space. Leary observes:

At any rate, they got a group of some business people to take seriously the idea of “How is San Francisco going to endure the flood of traffic that’s already coming in from the Golden Gate Bridge and the Bay Bridge? We can’t possibly do it.” The figures were coming out about what percentage of downtown Los Angeles was given over to automobile parking, most of it on the surface. They hadn’t yet begun many multiple-level parking facilities.

Eventually three counties — San Francisco, Alameda, and Contra Costa — committed to the transit system and developed the “BART Composite Report.” This had to be approved by their respective county supervisors in order for a bond measure to be placed on the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District-wide ballot in November of 1962.

In his oral history, longtime Republican politician and former Mayor of San Francisco from 1956–1964, George Christopher, remembers seeking the crucial aye vote of the fifth and still undecided Contra Costa County supervisor, Joe Silva. Silva had been under pressure from his constituents to vote no, because they would not directly benefit from the commuter rail but would bear the high price tag. Without Silva’s vote, the eventual passage of the measure in November and the $792 million bond issue may have been set back by years. According to Christopher, “The formation of BART is actually one of the funniest things that ever transpired,” involving a pre-dawn meeting and donuts.

I called him and I said “Supervisor, you’re the important man here. Now what are we going to do about this? All I’m asking is that you put it on the ballot and let the people decide whether they want it or not…. I said, “What time shall we meet?” He said, “Five o’clock in the morning.”… Sure enough we got up at four o’clock in the morning and we went over to Contra Costa County and finally found this restaurant. It turned out to be a little donut shop with no tables, no tables whatever, and we all sat around the counter. Here were all the teamsters, the truck drivers listening to every word we had to say…. I don’t know how many donuts we had, but we certainly filled ourselves.

Many hours and donuts later, Christopher had earned Silva’s crucial “yes” vote in support of the regional rail system. Christopher’s oral history is part of the Oral History Center’s “Goodwin Knight-Edmund G. ‘Pat’ Brown, Sr. Oral History Series,” which covers the California Governor’s office from 1953 to 1966, and is a gold-mine of fascinating anecdotes on city planning and transportation issues during that crucial decade.

Even before the bond issue was put on the ballot and approved in 1962, a consequential battle for regional power over transportation, including BART, was fought, ultimately resulting in a victory for local influence in this regional system. This battle was reflected in the approximately three-year long struggle between the Golden Gate Authority (GGA) and its younger competitor, the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG), for control over the planning and operation of transportation infrastructure in the region. Several oral histories from the Oral History Center discuss the importance of ABAG, which refers to itself as “part regional planning agency and part local government service provider.” In the oral history titled “Author, Editor, and Consultant: A Participant from the Institute of Governmental Studies,” Stanley Scott, a research political scientist at UC Berkeley, explains:

It came more from the large business interests, the Bay Area Council, with Edgar Kaiser being the chief proponent and front man, I guess you’d say, to create a Golden Gate Authority. That would incorporate the ports, the airports, and the bridges, the bridges being brought in essentially because they were very profitable organizations. So that one kind of came in, you might say, from the side, but at the same time, also involving regional restructuring.

This really upset the cities and counties, and quite a few others. A lot of people were concerned about it. A lot of people were concerned about just latching on to the bridges and tying them in with the airports and seaports. What are we going to do about all the other transportation problems? There was a great deal of concern.

It also exercised cities and counties that just did not want a major authority coming in from off the wall, so to speak. They began organizing themselves, and that was, in part, the genesis of ABAG. It was not the only reason for ABAG’s creation, but it provided substantial push in that direction. It had a lot to do with it. It scared the local people. That would have been in ’58, ’59, and ’60, that the Golden Gate Authority idea was kicked around. It was over a period of at least two years, and it could have been three, before it finally bit the dust.

T.J. Kent also addresses this theme about local influence and power sharing — with a focus on the role of ABAG — in his oral history, “Professor and Political Activist: A Career in City and Regional Planning in the San Francisco Bay Area.” Kent was a prominent city planner under San Francisco Mayor Roger Lapham in the 1940s, a deputy mayor for development under Mayor John Shelley in the 1960s, served on the Berkeley city council in the 1950s, and was a founder of UC Berkeley’s Department of City and Regional Planning.

According to Kent, former Mayor George Christopher opted to keep San Francisco out of ABAG because he felt that San Francisco was too important a player in the region to enter into an equal-representation regional government. His successor, Mayor John F. Shelley, reversed that policy, bridging the way to cooperation between the Bay Area’s largest city and the influential agency.

Shelley, with the board of supes [supervisors] backing him, he brought San Francisco into ABAG and appointed me as his deputy on the ABAG executive committee. I also served as the mayor’s deputy on the ABAG committee on goals and organization….The Committee prepared the regional home rule bill that was adopted by ABAG in 1966… It called for a limited function, directly elected, metropolitan government. That’s the key report.

Indeed, the publication of the Regional Home Rule and Government of the Bay Area report marked a huge milestone in the actualization of BART. ABAG, which was granted the authority by the State of California in 1966 to receive federal grants, included BART in the four elements of its metropolitan plan. Kent explains:

The first is the central district, enlarged and unified and focused in San Francisco; the second is a regional, peak-hour commuter transit system, which is BART and AC transit, plus the other transit systems serving San Mateo County, San Francisco and Marin and Sonoma counties; third is the open space system, to keep things from sprawling and for basic environmental reasons; and the fourth was comprised of the region’s residential communities, which shouldn’t get too dense, too overbuilt.

ABAG’s ability to receive and use federal money would prove vital to BART’s construction and continued operation. Furthermore, city and county representation on ABAG’s board — as opposed to zero locally elected officials in the defunct Golden Gate Authority — meant that cities likely had more of a say in the planning of BART than they would have had under the administration of the GGA.

Kent, then a Berkeley city councilmember, helped write the ABAG bylaws that balanced regional and local power. Kent believed in the importance of assigning enough power to regional agencies and districts like ABAG and BART, while also maintaining local autonomy. According to Kent — who throughout his oral history stresses the need to protect home rule wherever possible — counties that opted to stay in the Bay Area Rapid Transit District sometimes felt that the District was too restrictive or overbearing. But as a regional representative government with limited authority, conflicts were eventually solved. Kent remembers the back-and-forth between BART and Berkeley prior to the bond issue passing in 1962.

But those [counties] that were left in [the District], there were major battles in the BART legislation because the BART legislation had to give that agency that power and right. I was on the Berkeley council at the time and the battles were serious. There were many things that BART was required to do in consulting the cities and counties before the bond issue was proposed and voted on in 1962 and even after, which I think was good. They required BART to deal with Berkeley as an equal when Berkeley said, “We think—.” Berkeley got tremendous concessions from BART before the bond issue. You may not realize it, but the initial 1956 BART plan for the Berkeley line had it elevated all the way through downtown. Berkeley fought back before the bond issue vote of ʼ62 and got the middle third put underground.

Those counties that decided to stay in the District and cooperate with BART during its construction had a say in the decision-making process. Perhaps due to that fact, the 1962 district-wide bond issue surpassed the required 60% approval threshold, a result that came as a surprise to many political experts. Litigation and negotiations ensued with cities and counties across the Bay Area in the years that followed. But without the initial bond issue, BART could not have even begun construction.

Mary Leary observed that the impetus to create a regional, commuter rapid transit system — as well as the process of planning BART — did much to encourage local participation in politics. Even though ABAG was a regional entity with certain powers over local governments, Leary says that the agency allowed local governments a say in BART’s planning.

I think it was not unrelated that during this same era of local sharing in BART plans on a regional basis the Supervisors Association and the League of California Cities together launched ABAG, Association of Bay Area Governments, a voluntary group of cities and counties to discuss regional problems. It did not become a real regional government. In fact, I always felt it was created by those two groups to thwart moves towards regional government and to make sure cities and counties maintained their own strong voices. But it has been a significant forum and I think cooperation of the various governments around the Bay in planning BART gave it a good start. Interestingly, when planning got underway for where BART’s lines should run and stations should be, this became the first regional planning ever undertaken and local communities could see as some did that they were planning a sewer outfall just where the next-door neighbor town was planning a beach resort, that sort of thing.

In her oral history, Leary also noted a change in public perspective about public transit — away from the idea that no one would visit San Francisco if they couldn’t drive, to voters actually rejecting federal funds for a freeway connecting the Golden Gate and Bay bridges — and the relationship of BART to that.

Anyway, there was a good deal of political pride in the area that they had shared in developing BART from the very start, and it was part of the system’s success. Most other cities sat back and waited for Washington to provide funds for transit. Los Angeles never could get that much regional support. Of course, about that same time San Francisco was so supportive of the transit idea it rejected federal money for a freeway connection between the Golden Gate Bridge and the Bay Bridge. That really stirred a lot of national attention, saying “no” to millions or maybe billions.

Those interested in exploring the history of BART further, or learning more about the central themes of its history — local and regional government power sharing in the Bay Area, effective organization of regional governing bodies, and local participation in city planning, to name a few — can find much more in OHC’s numerous projects and individual interviews. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria from the OHC home page.

William Cooke is a fourth-year undergraduate student majoring in Political Science and minoring in History. In addition to working as a student editor for the Oral History Center, he is a reporter in the Sports department at UC Berkeley’s independent student newspaper, The Daily Californian.

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library has interviews on just about every topic imaginable. You can find the interviews mentioned here and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. We preserve voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page.

Related Oral History Center Projects

Covering the years 1953 to 1966, the Oral History Center (then the Regional Oral History Office) began the Goodwin Knight-Edmund G.Brown, Sr., Oral History Series of the State Government History Project in 1969. It covers the California Governor’s office from 1953 to 1966 and contains 84 interviews with a diverse set of personalities involved in Californian public administration. Topics include but are not limited to the rise and decline of the Democratic party, the impact of the California Water Plan, environmental concerns, and the growth of federal programs. This series includes the multivolume “San Francisco Republicans,” which includes the oral history of George Christopher, “Mayor of San Francisco and Republican Party Candidate.”

The San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge Oral History Project, launched in May of 2012, is a collection of 15 interviews that cover the construction of the Bay Bridge, maintenance issues, and the symbolic significance of the bridge in the decades after its construction. The majority of interviewees in this project spent their careers working on or around the bridge as architects, painters, toll-takers, engineers and managers, to name a few.

The California Coastal Commission Project traces the development of the only California commission voted into existence by the will of the people, from the campaign for Proposition 20 that created the agency in 1972 to the various development battles it confronted in the decades that followed. These interviews document nearly a half century of coastal regulation in California, and in the process, shed new light on the many facets involved in environmental policy.

Listen to the “Saving Lighthouse Point,” podcast, a collaboration between the OHC and the Bill Lane Center for the American West at Stanford University. “Saving Lighthouse Point” tracks the successful effort by citizens of Santa Cruz, with the support of the California Coastal Commission, to block the development of a bustling tourist and business hub on one of the last open parcels of land in the city.

Related Resources from The Bancroft Library

City and regional planning for the Metropolitan San Francisco Bay area, Kent, T. J., 1963. Bancroft Library/University Archives, Bancroft ; F868.S156K42

Open space for the San Francisco Bay area; organizing to guide metropolitan growth, Kent, T. J., 1970. University of California, Berkeley. Institute of Governmental Studies. Bancroft Library/University Archives. Bancroft ; F868.S156.57.K4

Regional plan, 1970–1990 – San Francisco Bay region, Association of Bay Area Governments, 1970. Bancroft Library/University Archives. Bancroft Pamphlet Double Folio ; pff F868.S156.8 A82

The BART experience: what have we learned? Webber, Melvin M.; University of California, Berkeley. Institute of Transportation Studies. 1976. Bancroft Library/University Archives. UC Archives ; 308m r42 W372 b

Bay Area Political Women Leaders Panel: The Importance of Networks

Support networks point to the generations of activists, staffers, fundraisers, and more who have helped the Bay Area become an incubator for powerful political women.

This is an exciting moment in women’s political history! Not only does August mark the 100th anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment, the recent announcement of Senator Kamala Harris as Vice President Joe Biden’s running mate on the Democratic ticket ensures that women’s political work is at the front of our minds. And Harris’s prospects on the national stage also highlight the Bay Area’s outsized influence in fostering women political leaders. This makes for the perfect atmosphere to celebrate the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project from UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center!

In the spirit of this celebration, on Wednesday, July 29, 2020, the Oral History Center hosted the Bay Area Political Women Leaders Panel with guests former San Francisco Supervisor Louise Renne, Pittsburg City Councilmember Shanelle Scales-Preston, and Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf. This all-star lineup of Bay Area politicos shared their personal journeys to elected office, as well as stories about local political women’s challenges and achievements.

Of particular note in this conversation was the importance of networks. Panelists explained how personal connections not only helped build leadership experience and fuel campaigns, but also pushed them to run in the first place. For Councilmember Scales-Preston, who is in her first term on the Pittsburg City Council, her relationships with other political staffers brought years of expertise to her campaign. And for Mayor Schaaf (and indeed Senator Harris), the women’s political recruitment and training organization Emerge America had a profound impact on her preparedness to seek elected office.

But these support networks also point to the generations of activists, staffers, fundraisers, and more who have helped the Bay Area become an incubator for powerful political women. For example, each panelist shared stories about those who paved the way for them and acted as mentors in political environments sometimes hostile to women. In addition to charismatic elected officials, it is the stories of these behind-the-scenes political players who form the basis of the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project.

As for what we should expect for the Bay Area’s political future, all panelists agreed: more women!

Now is the time to support this project and celebrate generations of the Bay Area’s political women. Join us in documenting this important history through the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project! The UC Berkeley Oral History Center is committed to putting voices in the historical record that might otherwise be lost, and providing the oral histories to the public at no cost. We are currently raising funds and need your help to undertake the expansion of this ambitious oral history collection. You can support this project by giving to the Oral History Center. Please note under special instructions: “For the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project.” To learn more about this project, please contact Amanda Tewes at atewes@berkeley.edu.

To catch up with the conversation with former San Francisco Supervisor Louise Renne, Pittsburg City Councilmember Shanelle Scales-Preston, and Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf, watch the panel here!

Louise Renne is a lawyer with the Renne Public Law Group, former San Francisco Supervisor (1978–1986), and former City Attorney for the City and County of San Francisco (1986–2001). She previously served as the General Counsel for the San Francisco Unified School District and as the City Attorney for the City of Richmond.

Shanelle Scales-Preston is a first-term member of the Pittsburg City Council, and District Director for Congressman Mark DeSaulnier. She previously worked for Congressman George Miller, and has been working in public service for nearly twenty years.

Libby Schaaf has been the Mayor of Oakland since 2015, and served on the Oakland City Council from 2011–2015. She was previously the Public Affairs Director for the Port of Oakland, and has a background in law.

“‘Rice All the Time?’: Chinese Americans in the Bay Area in the Early 20th Century”

Miranda Jiang is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. She is a UC Berkeley history major graduating in Spring 2022.

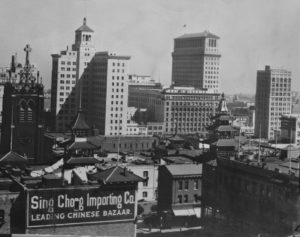

The Bay Area is home to San Francisco Chinatown, the first Chinatown in the United States. By the 1900s, there were second- and third-generation Chinese Americans living here who had spent their entire lives in the US. Interviews in the Oral History Center illuminate the experiences of these Chinese Americans who grew up in the Bay Area, and not just in Chinatown. What were the daily lives like of Chinese American youths living in Berkeley, or Emeryville, in the 1920s, 30s, and 40s? This is “Rice All the Time?”, an oral history performance about their experiences, brought to you in an audio format and performed by five young Chinese Americans.

This episode focuses on the experiences of one ethnic group. While we discuss Chinese American experiences with identity and discrimination, we recognize that this is just one part of a broad history of people of color in the United States. The murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and countless other Black people, have made it even more evident that systemic bigotry is far from being a relic of history. We hope that after listening, you will engage in further conversation about racism in our nation and the complex experiences of people of color who live in the United States.

“Rice All the Time?” features direct quotes from interviews with Royce Ong, Alfred Soo, Maggie Gee, Theodore B. Lee, Dorothy Eng, Thomas W. Chinn, Young Oy Bo Lee, and Doris Shoong Lee. They describe their experiences with racial discrimination, through schoolyard bullying and housing exclusion. Some describe Chinese food with fondness, some with disdain. You will hear about after-school Chinese classes and the presence, or lack of, a local Chinese community.

This is a culmination of work I began in the fall of 2019 – I wrote a blog post about the process of creating the script.

While creating this performance, I related to some of their experiences, and was also surprised to hear many of them. It’s made me reflect on my conception of Chinese American history and my own identity as a Chinese American. I hope that “Rice All the Time?” fosters similar introspection in you.

Performed by Maggie Deng, Deborah Qu, Lauren Pong, and Diane Chao. Written and produced by Miranda Jiang. Editing and sound design by Shanna Farrell.

Cantonese readings of Young Oy Bo Lee’s lines accompany the English to reflect the original language of her interview.

Transcript:

Audio: (music)

Shanna Farrell: Hello and welcome to The Berkeley Remix, a podcast from the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. Founded in 1954, the Center records and preserves the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world.

Lately, things have been challenging and uncertain. We’re enduring an order to shelter-in-place, trying to read the news, but not too much, and prioritize self-care. Like many of you, we’re in need of some relief.

So, we’d like to provide you with some. Episodes in this series, which we’re calling “Coronavirus Relief,” may sound different from those we’ve produced in the past, that tell narrative stories drawing from our collection of oral histories. But like many of you, we at the Oral History Center are in need of a break.

We’ll be adding some new episodes in this Coronavirus Relief series with stories from the field, things that have been on our mind, interviews that have been helping us get through, and find small moments of happiness.

Audio: (quotes spoken by performers, layered over each other)

(music)

Miranda Jiang: Hi, I’m Miranda Jiang, a history undergrad at UC Berkeley. You’re about to listen to an oral history performance I created called “‘Rice All the Time?’: Chinese Americans in the Bay Area in the Early 20th Century.” I originally intended for “‘Rice All the Time?” to be performed by a few of my fellow students in front of a live audience. But, of course, because of COVID-19 cancellations, we’re now bringing you this performance in an audio format.

“Rice All the Time?” presents perspectives of multiple Chinese people growing up in the Bay Area in the early 20th century. It places their words into conversation with each other, and it invites you, as listeners, to interpret them.

Before we get to the performance, I’d like to share with you a little background on the history of Chinese people in California.

Chinese immigration to the United States began in the mid-19th century. Thousands came to California as forty-niners during the Gold Rush. Racial resentment among white settlers in the West led to the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which barred the immigration of Chinese laborers to the US. The Act slowed the entrance of Chinese men, and denied entrance to virtually all women except those married to merchants.

Chinese immigration continued despite the Exclusion Act, which was only repealed in 1943, along with other anti-Chinese regulations. The number of Chinese women in the US increased steadily after 1900. Chinese Americans in the Bay Area and elsewhere built vibrant communities.

This performance is made of direct quotes from oral histories in the archival collection of the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library, here at UC Berkeley. It features the experiences of eight Chinese Americans who lived in the Bay Area from the 1920s to the 1950s. All, except one, were second or third-generation Chinese Americans who had spent all of their lives in the US. Alongside each other, these stories reveal a rich history and diversity of experiences within one ethnic group.

While you’re listening, I have some questions for you to keep in mind.

Think about what you know now of the Chinese American community in the Bay Area. Does hearing these experiences change your perception of their history? If so, how? What can their experiences with discrimination and identity teach us now, during the time of coronavirus and particularly visible racism against Asian people? How do you relate to these stories, many from almost a century ago?

After listening, I want to hear your feedback! Whether they’re answers to the questions I posed or other thoughts, please take a few minutes to fill out the Google form in the show notes. I appreciate any comments you may have, because your feedback will be super helpful to an article I’m working on about this project.

Now, please sit back and enjoy this performance of “Rice All the Time?”

Audio: (music)

Royce Ong (spoken by Diane Chao): There was not another Chinese family in Point Richmond, even a café or anything. Outside of my own relatives, I never had seen another Chinese.

Alfred Soo (spoken by Deborah Qu): … living in Berkeley, there weren’t very many Asians in my area. The Asians living in that area were probably my cousins.

Maggie Gee (spoken by Maggie Deng): It was before the onset of the war that brought in lots of people from elsewheres. Berkeley was integrated, in that sense… There were blacks, whites living in the neighborhood, quite a few Japanese, and some Chinese. More Japanese in my neighborhood than Chinese.

Theodore Lee (spoken by Lauren Pong): We didn’t know any Chinese. We lived in a neighborhood where we were the only Chinese. I went to a school where my family was the only Chinese in the school…

Dorothy Eng (spoken by Maggie Deng): [In Emeryville] there were three families, all Cantonese… It was an all white town. All [my mother] had was me, her children, and her husband whom she hardly knew.

Soo: … fortunately I didn’t experience any [teasing] that I can recall.

Eng: My father was very protective because he had seen the meanness to the Chinese, how they were treated, and he wanted to protect us because we were in a white community.

Theodore Lee: I wasn’t treated any differently because, remember now, these are people who are not snobby people; they’re working-class white, who tend, on the whole, to be friendly people. They’re not overly secure. There’s no snobbery. There’s no snobbery in our neighborhood. There was none.

Eng: … when I was in grammar school I hated it because I was never included, never included. All the years at grammar school I was not included in the classroom, I was not included in the playground. I can remember seeing myself going out during playtime, and I would be just standing there practically invisible. If I would go over to the rings because nobody else was there and start to swing, they would come and gather and push me off. The teachers were not there for you, the kids were just mean to you.

Audio: (sounds of children on a playground)

(music)

Ong: I think it was the Exclusion Act that didn’t allow the Asians to own property…“Asian” especially meant “Chinese…” The Exclusion Act had stopped them from immigrating and stopped them from owning property in the United States, especially California. I think they had their own law that was a little [more] stringent than the United States’ law. They were even segregated in the schools, when you read history.

Gee: I’ve lived around town in Berkeley, and Berkeley was a very difficult town to rent in, for non- whites … We really couldn’t find a place to live [there], because there would be a place available but when we came to see them, the place was rented. It became very discouraging… I sort of gave up. My sister, she’d call ahead of time and say that she was Chinese.

Thomas W. Chinn (spoken by Deborah Qu): We found out when we moved to San Francisco that the only place we could live in was Chinatown, because no one would rent to us or sell us a home outside of Chinatown.

Gee: I was hurt, more than anything else. Many years later I served on a commission on housing discrimination in the city of Berkeley. This was actually before the Rumford bill, and that was in the sixties. You’d think Berkeley, being a university city it’s an enlightened thing –– it’s just like any other city, though. People are frightened. If you allow a minority person to live [there], it would allow all the rest of the other minorities in. It’s really quite stupid… Yes, I was really disappointed in Berkeley.

Chinn: It was not a force of law; it was by word of mouth … no one wanted neighbors whose culture they did not understand or who could not speak to them in their own language.

Audio: (music)

Eng: When we moved to Oakland Chinatown I realized how different our family was from people I met in the church. Culturally, we were very different because we were brought up as a Christian family. We celebrated Christmas, Easter, 4th of July, all of the American holidays, also Thanksgiving. People in Chinatown did not celebrate these holidays. They celebrated the Chinese holidays, a big difference. When I joined the church, I realized this. They were all very curious about me because I was so different.

(Cantonese translation in the background, spoken by Lauren Pong): “旧金山的唐人街是 一个很好的社区。有好多山,好多缆车。又有中国餐馆、店铺、银行、医院…你需要的都有”

Young Oy Bo Lee (spoken by Miranda Jiang): San Francisco’s Chinatown was a nice community within a nice city. There were a lot of hills and cable cars. There were Chinese restaurants, shops, banks, hospitals and just about any kind of shop you would want. Also, Cantonese was the main dialect spoken so it felt comfortable. There were modern conveniences in all the houses. All of these things made the adjustment to the new country easier. Chinatown was a haven for the Chinese immigrant.

Audio: (sounds of Chinatown, erhu playing)

(Cantonese translation in the background, spoken by Lauren Pong) : 大部分人讲广东话,所以感觉好好。现代化的房屋,先进的设备,舒适的生活环境,新移民很容易过上新的生活

Doris Shoong Lee (spoken by Lauren Pong): At this time everyone in this area spoke Cantonese because most of the people in this area came from Guangdong. That is the one province in China that speaks Cantonese. So San Francisco Chinatown was all Cantonese speaking. It’s only been in the last maybe twenty, thirty years, since there has been a large influx of Chinese from other areas of China, that Mandarin is now spoken fairly commonly.

Chinn: My family hired some Chinese men to teach us how to write and speak Chinese, and how to read. But after spending all day in an American school, and then trying to revert back to a strange language that as children we never knew except for a few words from our parents, it was very hard. We were very poor Chinese scholars. That was one of the deciding factors for my parents––”Our children are getting too Americanized; they have no Chinese friends, they have no Chinese background. We think maybe we’d better move them back to San Francisco where they can live in Chinatown and learn more about their Chinese culture.”

Shoong Lee: I guess at that time there weren’t too many Chinese families that ventured and lived outside of Chinatown… San Francisco Chinatown has always been the very established community. But Oakland Chinatown at that time was rather small. Now it is quite different. It’s large.

Audio: (music)

Soo: I went to Chinese school in Oakland. So we’d take the streetcar to Oakland… In Chinatown. And we’d get there and start at 5:00 and start home at 8:00. That’s a long day.

Audio: (sound of streetcar and bell ring)

Shoong Lee: My dad wanted us to learn Chinese from the time we were in school. So we had tutors all the way through high school, my sister and I. The tutor came in five afternoons a week from four to six and Saturday mornings from ten to twelve…That’s a lot of Chinese…

Gee: When I was young, we used to have a teacher come to our house. It was really for my brother… to know Chinese. The girls got a little bit of Chinese…There used to be a name –– I forget what the word is, a very derogatory name for people who did not speak Chinese in the Chinese community. As I grew up, my mother was ashamed, a little bit. [laughs] Not really, though, but you know, people would always mention “Your children don’t speak Chinese.”

Ong: My mother knew English, but she always wanted to speak Cantonese, but I didn’t. I always answered in English, made her mad.

Gee: … with my generation, you didn’t want to speak Chinese, because you wanted to integrate. Didn’t want to eat with chopsticks, none of that. “Why are we having rice all the time?

Shoong Lee: I always loved my Chinese food… Sundays were always noodles at lunchtime. Those wonderful noodles. I can remember from the time I was maybe eleven, twelve, thirteen, on up, was that Sundays was when the New York Philharmonic came on the air. It was radio at that time, no television. Three o’clock in New York was lunch time in San Francisco. My sister and I would sit on the steps and have our lunch and listen to the New York Philharmonic.

Audio: (music, “Rhapsody in Blue”)

Ong: My mother cooked Chinese food and American food, but I don’t. I just eat regular American food.

Shoong Lee: We had Chinese meals for dinner but western breakfasts and lunch if we were home on the weekends. But dinner was always Chinese food. One of the things that Dad always wanted us to do was be able to name every dish that was on the table at night, and to speak Chinese at the dinner table.

Audio: (music, “Rhapsody in Blue”)

Chinn: We want to produce the concept of a Chinese-American who is striving hard to let people know that the Chinese part of a Chinese-American is something the Chinese are proud of, but at the same time they want to be known more as Americans.

Young Oy Bo Lee: I’m afraid the younger generation won’t understand this –– but holding on to traditions and customs is holding on to part of one’s identity. I hope that more of our young people will try to hold on to their Chinese identity and heritage.

(Cantonese translation in the background, spoken by Lauren Pong): 年轻一代不理解这 一点 —

保持传统同习俗,是坚持自己身份的一部分。我希望更多的年轻人会继续保持自己华人的身份同传统。

Chinn: I think if you are born a Chinese, sooner or later you come to appreciate the background and the culture of things Chinese. I know that among our friends, all our children that are growing up do not have that much interest in Chinese culture, but as they approach middle age and thereafter, then they pick up and want to learn more about their language and background.

Audio: (music)

Jiang: Thank you so much for listening to this oral history performance. I hope that it sparks your interest in the full interviews with each individual featured in the podcast. Many of these interviews include videos in addition to a printed transcript, and you can easily access them through the Oral History Center website and in the show notes.

Audio: (music)

Jiang: I’d like to thank our performers, Maggie Deng, Deborah Qu, Lauren Pong, and Diane Chao, for their wonderful work. I thank my mentors, Amanda Tewes and Roger Eardley-Pryor for making this episode come to fruition. Thanks so much to Shanna Farrell for being our editor and sound designer. And thank you to the people whose interviews were featured in this performance: Royce Ong, Alfred Soo, Maggie Gee, Theodore B. Lee, Dorothy Eng, Thomas W. Chinn, Young Oy Bo Lee, and Doris Shoong Lee.

Once again, don’t forget to send your reactions to this episode! I want to hear your thoughts, however long. There’s a link to a Google form in the show notes that includes a few questions about your listening experience.

Thank you for listening to “‘Rice All the Time?” I hope you enjoyed the performance and that you have a wonderful rest of your day.

Audio: (music)

Farrell: Thanks for listening to The Berkeley Remix. We’ll catch up with you next time. And in the meantime, from all of us here at the Oral History Center, we wish you our best.

Chinese-American Identity and Oral History Performance: Rewriting the Script

Miranda Jiang is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. She is a UC Berkeley history major graduating in Spring 2022.

In the fall of 2019, I joined an undergraduate research apprenticeship on oral history performance with Oral History Center interviewers Amanda Tewes and Roger Eardley-Pryor. Though I’d had some previous experiences with oral history, I wasn’t entirely sure what oral history performance was. I had my speculations: I was familiar with The Laramie Project and some other full-length plays which drew from oral histories. But no matter what the form of the performance would be, I understood that the project would take an approach to history that prioritized and shared the voices of ordinary people.

During the first few weeks of the semester, we discussed readings that fleshed out my understanding of oral history, then introduced me to multiple forms of oral history performance. Through readings such as Lynn Abrams’s Oral History Theory and Natalie Fousekis’s “Experiencing History: A Journey from Oral History to Performance,” I learned that the process of creating an oral history involves both the interviewer and the narrator (the person being interviewed). An oral history is a conversation. Both participants contribute to the content and direction of an oral history, and thus how an experience gets told. Oral history performance presents these experiences to the public, and places the experiences of multiple narrators in conversation with each other.

With these readings and assignments in mind, I searched through the Oral History Center’s vast archive of interviews to find sources for my own oral history performance. The only criteria I initially had in mind were that the subject I chose should be a story I knew little about, that I felt was undertold, and was centered in the Bay Area. I read interviews from the Freedom to Marry Project and the Suffragists Oral History Project, ultimately deciding on the Rosie the Riveter Project. It included interviews from people of African American, Chinese, Japanese, indigenous, and other backgrounds, and it was centered around the Bay Area.

I eventually decided to focus this performance on Chinese-American experiences in the Bay Area. I hoped that by focusing on this one group, I could have more time to flesh out the details of their lives. I do not have my own living grandparents to speak to, so hearing these stories about what young Chinese-American people like me had experienced growing up in California in the 1920s to 1950s made me feel connected to people who lived nearly a century ago. Hearing them also made me realize just how varied our experiences were.

Over the next weeks, I compiled a large annotated bibliography of quotes from relevant interviews, highlighting themes which continuously reemerged. In the spring semester, Amanda, Roger, and I shared many conversations about what it means to create a cohesive script out of direct quotes from oral histories. When we chose which quotes to group together, which to place in conversation with each other, and how we ordered and extracted quotes, we were interpreting each quote’s meaning. We constantly thought about how to assemble a script that highlighted common themes in the experiences of Chinese Americans, without taking narrators’ words out of context or imposing our own interpretations onto the quotes and our audience.

I soon found that by placing quotes of similar subjects next to each other, meaningful similarities and contrasts revealed themselves on their own. For example, many of the interviewers asked if the narrators had experienced teasing as children. Alfred Soo, Dorothy Eng, and Theodore Lee all described growing up in neighborhoods where they were among the only Chinese people there. Soo, who grew up in Berkeley in the 1920s, did not recall any teasing from other children. Lee, who grew up in the 1930s in Stockton, described not being treated any differently, emphasizing the lack of “snobbery” among working-class white people. Eng, who grew up in Emeryville in the 1920s, described being persistently mistreated by kids and teachers throughout grammar school. As a Chinese American who encountered racial insensitivity in school in the early 2000s, I expected that stories of children who grew up in the “age of exclusion” (1882-1943) would easily reinforce my own experiences. And yet, these oral histories showed a more complicated reality than I anticipated.

Another primary goal of this performance is to point the general public towards reading the full transcripts of the interviews. In the final script, there is a quote from Royce Ong, who states that he “just [eats] regular American food.” When I first read this, I was amused and annoyed by how he discounted Chinese food as something strange, when it was his own culture. But reading more of the interview, I found that his comments revealed more about his unique creation of a Chinese-American identity. He discussed “Chinese American” and “Chinese” as very distinct identities, with different political interests. To Ong, he could be a proud Chinese American as someone who didn’t eat Chinese food and who also learned only English as a first language.

Working on this performance made clear that no universal set of criteria comes with identifying as Chinese American. It made me aware of the vast multitude of experiences of other Chinese Americans, which are different from my own and different from each other. The format of the script brought the diversity of Chinese and American life to the forefront, and allowed each narrator to speak about their experiences as they occurred. It was up to the audience to observe and consider the contradictions between quotes.

The final script I created acknowledges that different Chinese Americans had unique experiences, while also highlighting similar struggles and activities within the ethnic group. Many anecdotes are relatable to me, today, and to other Chinese Americans in 2020. And ultimately, while some narrators leaned more towards embracing American culture, and others more towards also preserving Chinese traditions, all of them expressed the same conflicts with identity as Chinese people living in California.

By mid-March, we had created a final draft of the script after many sessions of cutting, rearranging, and reading out loud. We initially planned to give the eight-minute performance at the April 29th Oral History Commencement in the Morrison Library, with four or five student performers of Chinese-American backgrounds. When the campus closed due to COVID-19, we switched to an online podcast format, with the same script and number of performers.

The podcast version will be available on The Berkeley Remix this summer. I’m excited to be able to share this performance with more people using the magic of the Internet. I hope you’ll stay tuned for more!