Tag: politics

Library Trial: Znamia Digital Archive (Soviet-era periodical)

At the library, we have set up a thirty-day trial of Znamia Digital Archive through November 18, 2023.

The extensive archive of Znamia (Знамя, Banner), a highly regarded Soviet/Russian “thick journal” (tolstyi zhurnal), covers more than nine decades and is a rich source of intellectual and artistic contributions. This monthly publication has been a vibrant platform for literature, critical analysis, philosophy, and, at times, political commentary.

Originally introduced in January 1931 as LOKAF (Локаф), an acronym for the Literary Association of the Red Army and Navy, the journal officially adopted the name Znamia, which translates to “Banner” in English, in 1933. Throughout its history, Znamia has played a crucial role in presenting the works of renowned authors such as Anna Akhmatova, Alexander Tvardovsky, Yevgeny Yevtushenko, Konstantin Paustovsky, Yuri Kazakov, and Yuri Trifonov.

During the era of Perestroika, starting in 1986, Znamia underwent a significant transformation and became one of Russia’s most widely read literary journals, serving as a herald of the Perestroika movement.

Access Link: https://libproxy.berkeley.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fdlib.eastview.com%2Fbrowse%2Fudb%2F6250

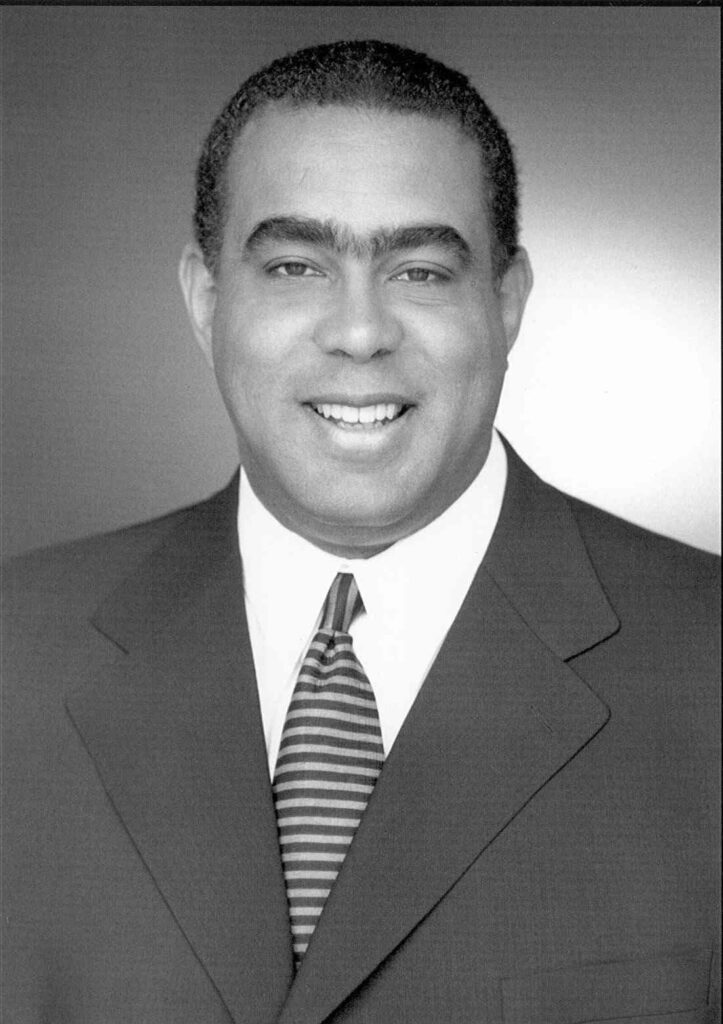

Hon. Kevin Murray: California State Assembly (1994-1998) and California State Senate (1998-2006), oral history release

New oral history: Hon. Kevin Murray

Video clip from Kevin Murray’s oral history about his political role models and becoming more a legislator than a politician:

Kevin Murray represented regions of Los Angeles as a member of the Democratic party in the California State Assembly (1994-1998) and in the California State Senate (1998-2006), until he retired due to term limits. Murray and I recorded over five hours of interviews about his life and career in May 2021 as part of the Oral History Center‘s contributions to the California State Government Oral History Program. Murray’s oral history reveals ways he capitalized on opportunities as they arose throughout his life. In the process, he became an influential leader in the California Legislature, including as chair of the state’s Democratic Caucus and the California Legislative Black Caucus.

Many of Kevin Murray’s life stories reflect a kind of American dream narrative for Black middle-class families in Los Angeles. Murray was born in the spring of 1960 in the westside community of View Park, where he still lives and now raises his own family. Both of Murray’s parents graduated from college, and around the time of his birth, Murray’s father transitioned from work as an aerospace engineer to working in Los Angeles city politics and eventually in state politics. Around that time, their View Park neighborhood experienced white flight, which according to Murray resulted with an influx of middle and upper-middle class Black families of doctors, lawyers, dentists, and political figures who became his role models. At his parents’ insistence, Murray attended elite Los Angeles middle and high schools. During college, while earning a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration from California State University, Northridge, Murray began booking music and entertainment acts on campus. After graduating in 1981, Murray’s college entertainment experiences led to him start work in the infamous mail room at the William Morris Agency in Beverly Hills. While working at William Morris, Murray earned a Master’s in Business Administration from Loyola Marymount University in 1983, and in 1987, he earned a Juris Doctor from Loyola Law School. Prior to his political career, Murray provided consulting and management services to artists in the entertainment industry while also practicing law in the areas of entertainment, real estate, insurance, and dependency.

Due to his father’s work in L.A. politics, Murray recalled as a child attending barbecues and breakfasts at the homes of legends in California politics like Big Daddy Jesse Unruh and Black political leaders like Mervyn Dymally, Julian Dixon, and Tom Bradley. From his young exposure to powerful politicians, Murray learned they were simply people, not intimidating icons. Eventually, Murray came to believe, rightfully, that he, too, could become a political leader. When an opportunity to run for the California Assembly arose in the early 1990s, Murray seized that chance and won his first election to the California Assembly in 1994. His father was, by then, also serving in the Assembly, which made them the first-ever California Assemblymembers to serve as father and son.

Video clip from Kevin Murray’s oral history about California’s North-South power politics:

Murray described himself as more of a legislator than a politician. In the Assembly, Murray worked with Speaker Willie Brown and quickly became a leader who, over the next twelve years, served in both the California Assembly and Senate. Murray was elected as a Democratic member of the California State Assembly from the 47th District in Los Angeles from 1994-1998, where served as Chair of the Transportation Committee. In the California State Senate from 1998 to 2006, Murray represented the 26th District based in Culver City, California, and served as chair of the influential Appropriations Committee, the Transportation Committee, the Democratic Caucus, and the California Legislative Black Caucus. Murray also served on the California Film Commission.

Most of Murray’s oral history explored his years of political work in Sacramento where he passed numerous bills, including one of the nation’s first laws on identity theft (AB 157, the Consumer Protection: Identity Theft Act); bills on “Driving while Black”; education bills to address the digital divide and ensure California students had access to the internet (then called “the information superhighway”); bills protecting victims of domestic violence; a bill protecting houses of worship from hate crimes; and many others, including a bill eventually vetoed by Governor Pete Wilson that would have enabled Californians to register to vote online, to sign a petition online, and to vote via the internet as early as 1997.

While Murray’s oral history details his legislative efforts, he also reflected broadly on a variety of topics, including key differences between the California Assembly and Senate; on influential committee assignments; on intra-caucus relationships between the Black Caucus, Latino Caucus, API Caucus, and the Women’s Caucus; on North-South power politics in California; on his distaste for term limits and the importance of legislative staff; and on his political role models. Murray concluded his oral history with brief a discussion of his post-legislative life in Los Angeles with his wife and their two children, including reflections on the 2008 election of Barack Obama and the Black Lives Matter marches of 2020.

Video clip from Kevin Murray’s oral history about intra-caucus relationships in the California Legislature:

About the California State Government Oral History Program

Kevin Murray’s oral history was conducted in collaboration with of the California State Government Oral History Program, which was created in 1985 with the passage of AB 2105. Charged with preserving the state’s executive and legislative history, this state Program conducts oral history interviews with individuals who played significant roles in California state government, including members of the legislature and constitutional officers, agency and department heads, and others involved in shaping public policy. The State Archives oversees and directs the Program’s operation, with interviewees selected by an advisory council and the interviews conducted by university-based oral history programs. Over the decades, this collective effort has resulted in hundreds of oral history interviews that document the history of the state’s executive and legislative branches, and enhance our understanding of public policy in California. The recordings and finished transcripts of these interviews are housed at the State Archives. Additionally, Kevin Murray’s oral history is available online in the Berkeley Library Digital Collections.

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Video clip from Kevin Murray’s oral history about California Senate and Assembly differences and good committees:

Video clip from Kevin Murray’s oral history about term limits for California legislators and the role of legislative staff:

SIGLA: States and Institutions of Governance in Latin America Database

SIGLA (States and Institutions of Governance in Latin America, www.sigladata.org) is a multilingual digital database that freely provides information on legal and political institutions in Latin America. The beta version of SIGLA offers data on national-level institutions in Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico, as well as on international institutions. Ultimately, SIGLA will provide cross-nationally comparable, current and historical, qualitative and quantitative data on over 50 legal and political institutions in 20 Latin American countries in English, Spanish, and Portuguese.

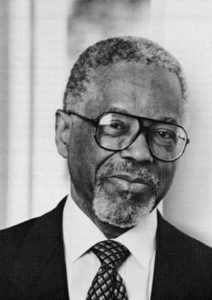

Hon. Loni Hancock: Member of the California State Senate, December 2008-November 2016

In spring 2021, I had the pleasure of interviewing the Hon. Loni Hancock for the California State Archives State Government Oral History Program. As an interviewer, one of my major areas of interest is the history of women’s political work, and Loni Hancock’s name appears over and over in the course of this study. Indeed, her life and work are integral to understanding California’s recent political history and the greater inclusion of women in elected office.

Loni Hancock is a former California State Senator (2008-2016), California State Assemblymember (2002-2008), Mayor of Berkeley (1986-1994), and Berkeley City Councilmember (1971-1979). Hancock was born in 1940 in Chicago, Illinois, and grew up in New York City. She attended Antioch College, Cornell College, and graduated with a BA from Ithaca College in 1963. Hancock later earned a MA from the Wright Institute in 1978. In addition to serving in elected office as a Democrat, Hancock also previously worked as the regional director for ACTION in the Carter administration, the director of the Shalan Foundation, and headed the Western Regional Office of the Department of Education in the Clinton administration. She currently partners with East Bay Supportive Housing Collaborative to advocate for supportive housing for people with serious mental illnesses, and is working to preserve Berkeley’s architectural heritage.

Hancock moved to Berkeley, California, in 1964 amidst the community’s reckoning with school desegregation and the Free Speech Movement. This zeitgeist in 1960s Berkeley inspired Hancock to follow her own interests in political activism. Indeed, it was her involvement in the local peace movement that propelled her into electoral politics. In her interview, Hancock explained, “Berkeley is a place where things begin. And whatever is in the air here has, I think, encouraged us to be standing up for what we believe is right, and arguing it out among ourselves.”

After an unsuccessful first campaign in 1969, Hancock won election to Berkeley City Council in 1971. For a time, she was the only woman on this governing body. Hear Hancock reflect on gendered expectations for Berkeley City Councilmembers in the 1970s:

After her time as Mayor of Berkeley, as well as work in several Democratic administrations and nonprofits, Hancock felt she could continue to contribute to her community by running for legislative office—first as a California State Assemblymember and then as a California State Senator. During her time in the California Legislature (2002-2008, 2008-2016), Hancock worked on many important issues. Notably, she was a major proponent of environmental legislation. Hancock introduced SCA-5 (later approved by voters as Proposition 25), which proposed passage of state budgets with a simple majority vote rule. She also advocated for criminal justice reform, including funding for prison education programs. Of this work, Hancock explained,

“One of the things we did was get a lot of prison education funded and implemented and get more money for rehabilitation programs. And actually, one of my best bills that was a my-idea bill was we gave full reimbursement for community colleges in California to run transfer-level courses in our state prisons. The idea being that you would get your basic first two years of college done, and then you could transfer to a UC or CSU on release…The recidivism rate goes down to virtually zero when that happens, so anyway, it makes safer communities, is what it does.”

Hancock’s legislative contributions have certainly helped shape recent California politics. But as the California State Legislature still struggles with gender parity of elected officials, her presence and perspectives as a woman in both bodies have also been key. In thinking about the strides toward greater representation of women in California politics, Hancock reflected,

“Well, we had our first woman speaker [in the Assembly], Karen Bass. We had our second woman speaker, Toni Atkins, who’s now the [Senate] pro tem. Those were milestones, really important milestones. You know, also, Karen was the first woman of color, and I’m guessing that Toni might be the first LGBTQ woman as a head [in California State government]…so you have women in leadership, which I think makes an interesting difference, and more women…So you know, there’s definitely progress, definitely.”

And Hancock’s tenure in California politics has certainly been a part of this progress. Read Loni Hancock’s oral history interview to learn more about her life and work in California politics!

Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, keyword, and several other criteria.

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library has interviews on just about every topic imaginable. You can find the interviews mentioned here and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. We preserve voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public.

Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

JoAnn Fowler: Building the Foundations of SLATE

The Oral History Center has been conducting a series of interviews about SLATE, a student political party at UC Berkeley from 1958 to 1966 – which means SLATE pre-dates even the Free Speech Movement. The newest addition to this project is an oral history with JoAnn Fowler, who was a founding member of the organization in the late 1950s.

JoAnn Fowler is a retired Spanish language educator and was a founding member of the University of California, Berkeley student political organization SLATE in the late 1950s. Fowler grew up in Los Angeles, California. She attended UC Berkeley from 1955 to 1959, where she became active in SLATE and served in student government through Associated Students of the University of California (ASUC). After completing a master’s degree at Columbia University, she worked as a teacher, mostly in Davis, California. Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

I have previously written about the contributions of women members of SLATE and their sometimes complicated feelings about gender roles in this student political group. Fowler, however, did not feel that being a woman was not an obstacle for her in SLATE, and her interview includes memories of her own role in shaping the organization.

Fowler recalls being an outspoken SLATE member from the start. At her first meeting with the group in the fall of 1957, she recalled being overwhelmed by the advanced political theory many of the group discussed, and by one faction that she perceived “wanted to sit around and talk these things to death and not try to take any kind of action.” She felt that in order to be politically effective, the group had to take another approach:

I’m very verbal, I’m not shy at all, I speak right up, I don’t care, I have nothing to lose here. I say that, “You have to do something within the campus, you have to work within the campus. If you want to get all these things done, you have to get elected and do things on campus.”…So that’s the position I take, and that’s the position that Pat Hallinan takes, and so we win over the majority of these people…

Perhaps Fowler’s greatest contribution to the group was that in the spring of 1958 she ran for and won a position with ASUC on the SLATE ticket. This made Fowler and Mike Gucovsky the first SLATE members to have a voice in student government at UC Berkeley, and being able to affect progressive political change from positions of campus leadership was a key goal of the group. In speaking of her campaign platform, Fowler remembered:

If you were to name anything, we ran on all of it, but not all of that could be addressed during the campaign. Basically, it was: freedom of speech was addressed through [being] against the [House] Un-American Activities Committee and also by the relationship between professors and the students that should be confidential and the anti-Loyalty Oath. Then there was civil liberties in the South; in Berkeley with that housing ordinance that came up for vote; and on the campus that no fraternity or sorority should discriminate.

She continued discussion of that ASUC campaign, saying:

This was encouraged by Mike Miller. I didn’t mind running—that was going to be great—but I did mind speaking to big groups. I hadn’t had a lot of experience doing that, so he encouraged me to do that. I went around only two nights that I remember, and it was only to men—I never spoke to women—and only at the co-ops. That was my background; I’d come out of co-ops. I’d go in at dinnertime and I would speak for two minutes, maybe somebody introduced me and maybe somebody didn’t. I’d speak for two minutes to those very immediate concerns that I thought would be very appealing, and I would have this overwhelming applause. But I felt that anybody, any woman could have stood up there and gotten this overwhelming applause, because that’s the kind of applause I felt it was. I don’t know, maybe that’s just me. I don’t know who else spoke there. I don’t know if men spoke there, if other independents have reached out, I have no idea.

Even after she graduated from UC Berkeley in 1959, the lessons she learned from SLATE stayed with her. While living in Davis, she worked at a Hunt’s tomato factory, where she attempted to organize the office workers. Later, she headed the Davis Teachers Association, supporting a raise in teachers’ salaries. These organizing efforts didn’t always succeed, but Fowler saw them as part of a larger political project she’d been passionate about since her time in college. She explained, “But I did my bit, and so without SLATE, I wouldn’t have…tried, no, I wouldn’t have tried.”

Reflecting on how her involvement with SLATE impacted her life, Fowler observed:

I think it was one of the greatest experiences of my life. I never would have been as politically aware. I didn’t have that background, I didn’t take political science, I didn’t take sociology; I took economics, I took psychology. I never would have been as aware or as active as I was, I wouldn’t have had a group. When I lived in an apartment, I didn’t have a social group or I didn’t have—you were going to come on campus and leave campus because you certainly didn’t meet too many people coming out of that lecture hall of 500 people. I’m glad I have that experience, very much so. It was a good time in my life.

To learn more about JoAnn Fowler’s life and political work, check out her oral history! Find this interview and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

Oral History and Political Organizing

By Eleanor Naiman

In 2020 Eleanor Naiman was a Biden-Harris campaign field organizer for the Nebraska Second Congressional District, working remotely to gain an electoral vote for Democrats. She is a recent graduate of Swarthmore College and completed an internship for the Bay Area Women in Politics Project with the Oral History Center in summer 2019.

Each of the 4,150 phone calls I made as a field organizer with the Biden-Harris campaign had a clear and stated purpose: to establish a voter’s support of Democratic candidates and to convince them to volunteer at a virtual phone bank. A detailed script drafted by the Biden HQ provided the framework for each conversation. Designed to maximize efficiency and recruitment shifts, the script encouraged organizers to get to a “hard ask” as quickly as possible: “We have phone banks at 4:30pm Central every day this week,” I’d explain. “Can I put you down for Monday and Wednesday?”

The direct nature of our recruitment script initially threw me off. My summer as an intern for the Oral History Center’s Bay Area Women in Politics Project taught me to take a subtler approach to questioning. I learned to ask open-ended questions that allowed narrators to tell their stories with authenticity and autonomy. I knew to prioritize the needs of my narrator over my own research objectives, working collaboratively to construct a life story that felt true to both history and memory.

In those early days of campaign work, I longed for the opportunity to sit down with each voter, as I had at the OHC, equipped with pages of notes of background research and confident in the strength of the relationship we’d built over pre-interviews and email correspondence. I missed the warmth and familiarity of in-person conversation; due to the nature of field organizing in a pandemic, the entirety of my conversations with voters took place over the phone or on Zoom. My conversations with voters seemed unpredictable and somewhat chaotic. Parents answered as they shuttled their kids to school, retirees picked up with the afternoon news blaring on a nearby TV, wives declined on behalf of husbands on the farm and in the field. I never knew where a conversation with a voter would take me. Would they hang up abruptly, perhaps after a quick jab at my candidates or an angry request that I take them off the list? Or would they linger on the phone, desperate for some form of human connection after months of pandemic-imposed isolation?

The conversations that fell somewhere between those two poles posed the greatest challenge. Somehow, in the five minutes allotted for each conversation, I needed to transform a weary voter into an eager volunteer. I found myself increasingly relying on oral history methodology to quell my anxiety about cold calls and hard asks. After all, I reminded myself, despite their obvious differences in form and purpose, an oral history interview and a voter outreach call posed the same basic problem: how to build trust through dialogue. I found myself listening as diligently as I had at the Oral History Center, noting and adopting the tone and lilt of a voter’s voice, sometimes even subconsciously, in an attempt to build rapport before my voter’s interest waned and I lost a potential volunteer. This meant performing in a matter of seconds the careful assessment of intersubjectivity I’d studied as an OHC intern. How did the voter perceive me? How did I see them? I knew that each conversation would require a balance of give and take, leaving both of us changed by its end. To a grandmother, alone in an assisted living facility, I became a granddaughter, or perhaps a memory of the political organizing and idealism of her youth. To a young voter, I became a friend and peer, commiserating about classwork and college stress. I reminded myself to that even on this small scale, the quality of my listening mattered just as much as the efficiency of my hard ask. Returning over and over to the tools and practices of oral history, I built relationships with voters whose dedication to change and hope for the future fueled my long nights and countless hours on Zoom. Together, we formed a community that ultimately flipped Nebraska’s second congressional district.

I came to appreciate the constant thrill of this sort of speed-interview. By November, I had learned to love catching a voter in motion, getting a peek into homes far from my own, and hearing anecdotes of daily struggle, loss, and hope that consistently reinforced the importance of this work. As I sat at my desk in my pandemic office, cut off from the world yet never closer to it, I felt an immense gratitude for the thousands of people who had let me into their lives. It was the same sense of awe and of appreciation that made me fall in love with oral history in the first place.

Panel with Bay Area Women Political Leaders on Zoom July 29

Come celebrate the launch of the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project by joining us for a conversation about the history and future of Bay Area women in politics with former San Francisco Supervisor Louise Renne, Pittsburg Councilmember Shanelle Scales-Preston, and Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf!

The panel discussion will take place over Zoom on Wednesday, July 29, from Noon—1 p.m. Pacific Time. Click here to RSVP. We will be moderating Q&A. If you would like to submit a question to the panelists, please email it beforehand to Amanda Tewes at atewes@berkeley.edu.

August 2020 marks the hundredth anniversary of women’s suffrage, and the anticipated nomination of a woman Democratic vice presidential candidate — both milestones of the national political roles for women. Here in the Bay Area, women have been driving political campaigns and activism for generations. Through first-person oral history interviews, the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project from UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center will document and celebrate the lives and work of these political women, some of whom have been unsung.

To kick off this oral history project and to celebrate these milestones, join us for a panel conversation with three talented Bay Area women public officials: Louise Renne, Shanelle Scales-Preston, and Libby Schaaf! This panel will include discussion about the historical and current roles of Bay Area political women, lessons from across generations, as well as the challenges and opportunities facing women in politics.

Louise Renne is a lawyer with the Renne Public Law Group, former San Francisco Supervisor (1978–1986), and former City Attorney for the City and County of San Francisco (1986–2001). She previously served as the General Counsel for the San Francisco Unified School District and as the City Attorney for the City of Richmond.

Shanelle Scales-Preston is a first-term member of the Pittsburg City Council, and District Director for Congressman Mark DeSaulnier. She previously worked for Congressman George Miller, and has been working in public service for nearly twenty years.

Libby Schaaf has been the Mayor of Oakland since 2015, and served on the Oakland City Council from 2011–2015. She was previously the Public Affairs Director for the Port of Oakland, and has a background in law.

The UC Berkeley Oral History Center is committed to putting voices in the historical record that might otherwise be lost, and providing the oral histories to the public at no cost. We are currently raising funds and need your help to undertake the expansion of this ambitious oral history collection. You can support this project by giving to the Oral History Center. Please note under special instructions: “For the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project.” To learn more about this project, please contact Amanda Tewes at atewes@berkeley.edu.

“They Got Woken Up”: SLATE and Women’s Activism at UC Berkeley

For students across the country, college is a time of political awakening. And perhaps no other university has earned its reputation for radical student politics quite like UC Berkeley. Indeed, mid-century political activism around civil rights, the Vietnam War, and the Free Speech Movement has shaped how students, faculty, and administrators experience life at Berkeley today.

However, one important part of Berkeley’s political history that often gets left out of the conversation is the New Left student political party SLATE. SLATE — so named because the group backed a slate of candidates who ran on a common platform for ASUC (Associated Students of the University of California) elections — operated between 1958 and 1966, and ignited a passion for politics in the face of looming McCarthyism and what many perceived as the University of California’s encroachment on student rights to free speech. These students translated political theory they learned in the classroom to action, even when it went against University policies. Perhaps SLATE’s most important ideological contribution to Berkeley’s campus and to other social movements is the “lowest significant common denominator.” This concept allowed the group to form a big tent coalition between Marxists, liberal Democrats, and others by only choosing political positions and actions that the whole group could agree on. As a result, the group became involved with civil rights, labor organizing, and anti-war protests on campus and across California. Most notably, in May of 1960, SLATE and other student activists protested the HUAC (House Un-American Activities Committee) hearings at the San Francisco City Hall. In response to the peaceful sit-in, police blasted students with fire hoses and dragged them down stairs before placing them under arrest. This event was emblematic of SLATE’s commitment to activism, even when it came at personal risk.

In recent years, the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library has conducted a series of interviews with members of SLATE to keep alive memories of the group’s influence on ideology and political infrastructure at UC Berkeley.

An essential part of SLATE’s story is the contributions of its women members. SLATE operated at a time before the women’s movement, but its work became an important introduction to political organizing for a generation of women students at Berkeley. These women were dedicated members of the group, but often felt sidelined in SLATE leadership. And yet, their work helped to change political culture and campus life at Berkeley. Three of these groundbreaking Berkeley women are Cindy Lembcke Kamler, Susan Griffin, and Julianne Morris.

Cindy Lembcke Kamler was just a freshman when she connected with SLATE in the spring of 1958, drawn in by the political ideals of the group dominated by male upperclassmen and graduate students. Susan Griffin and Julianne Morris were among the second generation of SLATE activists and joined the group around the same time in 1960 — after the famous HUAC protest.

All of these women came from politically left families who feared encroaching McCarthyism. Griffin and Morris also had connections to Judaism. These backgrounds helped ignite a political consciousness in these women that led them to SLATE.

Certainly Kamler, Griffin, and Morris’s oral histories contribute to the larger archive of SLATE history, but they also speak specifically to their experiences as women in this group. For instance, Griffin and Morris recalled instances of feeling marginalized and of being left to do what Morris called the “scut work,” like mimeographing fliers and cooking for hungry activists. This work, while essential to maintaining operations, felt to them like gendered tasks. For her part, Kamler doesn’t remember gender discrimination in SLATE. She insisted, “Oh, no, I never made coffee or any of that stuff.” And yet, Griffin recalled that several years later at a meeting of SLATE women in the 1970s,

“We were recounting how there was this prejudice against us and we were never allowed to have leadership positions. And husbands and boyfriends and guys from SLATE showed up at this meeting and started making fun of us and broke the meeting up. They thought that was the end of the story. Little did they know, [laughs] that was just the beginning of the story.”

These tensions came to a head at a 1984 SLATE reunion in which women newly empowered by feminism expressed displeasure with the way they had been treated while working for the campus political group. Many of the men denied there had been discrimination, but others took it to heart and sincerely apologized. Morris explained, “There were a lot of women who were really angry about how it had been. I don’t know that I was angry, in the sense that I really felt it was a different time and one can’t judge one time by another. But there was no question that that’s the way it was, and that’s what kind of was accepted.” Watching these events unfold, Kamler recalled, “I was just sitting there stunned. I didn’t do any of that stuff. I ran for office, I got elected, I was chairperson.”

Indeed, while there may have been invisible barriers for many of the women involved in SLATE, there were still opportunities to grow as individuals and leaders. Kamler ran for second vice president in the spring of 1958 and lost, but ran again for representative-at-large in spring of 1959 and won. She also served as the chair of SLATE for some time, helping to shape the group’s platform and activist agenda. Even Griffin and Morris were encouraged to run for ASUC office in the early 1960s, and had to learn how to campaign and feel confident in public speaking. Morris especially found running for office to be a formative experience. She remembered,

“And that was, for me, a big experience, because as I said, I was shy in terms of speaking out and I didn’t think that I could do it. And Mike Miller kept urging me to do it and saying, ‘You can do this. I’ll help you if you want, but you can do this! You’re going to be able to go to all of these fraternities and talk to them about ROTC. I just know you can do it.’ So I did it, and I really was very frightened about doing it, and I actually did fine. So that was, for me, kind of a breakthrough, that I was able to do something like that, because it wasn’t easy for me at the time.”

But as their lives became less centered around the UC Berkeley campus, these women drifted away from SLATE. Kamler married and left the group after the spring of 1960. Griffin and Morris had decreased their participation in SLATE or left campus entirely by 1964. And yet, as their oral histories reveal, the experiences these women had as Berkeley undergraduates in this student political party shaped their perspectives about politics and activism for years to come. For both Griffin and Morris, this activism took shape as involvement in the women’s movement. Griffin explained, “The guys may not have known it, but they were training feminist activists in all that period.”

Thinking about the longer arc of SLATE’s impact on the lives of its dedicated members, Morris recalled of a reunion in the 1990s:

“One of the things that we did was that we went around as a group and talked about what our lives were like now. And no one in that whole group went into business. Everybody was an organizer, a teacher, a social worker, a psychologist. It was so interesting that this group of people kind of, in some ways, stayed true to what we all went through in college. It really formed our lives.”

But most importantly, what these women learned from their time with SLATE was the importance of building and sustaining community in activist groups. For Morris, joining SLATE helped her find a place where she belonged. Griffin pointed to organizations of politically like-minded individuals as ways to create belonging and “joy” through an almost spiritual experience of protest.

And yet, the political work of Cindy Lembcke Kamler, Susan Griffin, and Julianne Morris wasn’t just personally fulfilling. For these individuals and generations of other women students, their political activism at UC Berkeley left an indelible mark on the campus. In thinking of this legacy, Morris reflected, “…it was one of the first…of the Left student movements. And I think it influenced a lot of people in that regard…I’m not at all sure that the Free Speech Movement would have happened without SLATE.” She concluded, “I think we were very successful in those years. We got a lot of people elected to the campus political organization, and I think people started thinking, at Cal, a little differently. They got woken up in a way that perhaps they would not have been.”

To learn more about these activist women at Berkeley and the history of this early student political party, check out the Oral History Center’s SLATE Oral History Project.

Exhibit: Institute of Governmental Studies Centennial

The Institute of Governmental Studies is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year! A hundred years ago, as efforts to reform government corruption were taking root across the country, IGS was founded by political scientists who saw an opportunity to build public administration into an academic discipline to educate new generations of civic leaders. The library has been the heart of IGS since its founding, and holds more than 400,000 items, many of them unique reports, pamphlets, bibliographies, and other ephemera.

The Institute of Governmental Studies is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year! A hundred years ago, as efforts to reform government corruption were taking root across the country, IGS was founded by political scientists who saw an opportunity to build public administration into an academic discipline to educate new generations of civic leaders. The library has been the heart of IGS since its founding, and holds more than 400,000 items, many of them unique reports, pamphlets, bibliographies, and other ephemera.

An exhibit now on display in the IGS Library highlights the people and projects that built IGS over the last century. The Institute will be celebrating its centennial with events and programs throughout the year, so please check igs.berkeley.edu for updates.

The IGS Library is open to the general public and the campus community from 10am-5pm, Monday through Friday. Email igsl@berkeley.edu or call us at 510-642-1472 with any questions.

OHC Director’s Column – February 2020

From the OHC Director…

Berkeley students and researchers from around the country reach out to us, especially during Black History Month, interested in our oral histories with African Americans. We always point people in the direction of our African American Faculty and Senior Staff oral history project, otherwise known as The Originals. And there is a good reason we do that: this project features seventeen lengthy and substantive oral histories with leading and pioneering UC Berkeley scholars and administrators (more on this below). But limiting our reference to this single project does service neither to OHC’s full collection nor to the amazing and accomplished individuals interviewed for other projects or simply based on their own merits. In preparation for this month’s column, I spent a day digging into our collection in an effort to uncover a host of hidden gems — in this case, interviews with African Americans whose living memories date to the early 20th century (at least) and offer first-person insights into the life of a Tuskegee airman, the contours of the West Coast jazz scene, the role of women in the Black Panthers, and much more.

The migration of African Americans from the American South to the industrial centers of Northern California in World War II changed those who moved, along with the places they moved to. Drawn to jobs in places like the Kaiser Shipyards in Richmond, California, these migrants set down their roots in the Bay Area. In some interviews from the Rosie the Riveter / World War Two Home Front oral history project, Black “Rosies” tell about their lives in Jim Crow South, about the migration north and the hope for a better life, and about their experiences working in wartime industries and experiencing both greater opportunity but still discrimination based on race. Of the 197 Rosie project oral history, about a quarter are with African American women and men. It is likely folly to pull out one interview from this group, but I’m certain people will be interested in the story of Betty Reid Soskin, who not only worked in Richmond during the war but decades later became a ranger with the National Park Service at the Rosie the Riveter National Historic Site. Reid Soskin continues to work at the park today — at the ripe young age of 98!

One chapter in the Second World War that tragically demonstrated the enduring power of racism was the Port Chicago Disaster of 1944. The majority of the 320 killed and 340 injured in this accidental munitions explosion were African American. The eight oral histories of the Port Chicago project were recorded in the late 1970s and early 1980s by UC Berkeley scholar Robert Allen (whose life history interview we will be released this spring).

Our documentation of the African American experience in the Bay Area continues well past World War II. In a few major projects, Black East Bay residents — and their neighbors — offer accounts of not only the transformation during war but the important decades that followed. The On the Waterfront project follows several narrators through these decades. In the Oakland Army Base project, we hear from several African Americans (Charles Snipes, Cleophas Williams, Davetta Thibeaux, Ellen Wyrick-Parkinson, Elois Thornton, George Bolton, George Cobbs, Gordon Coleman, Grant Davis, Leo Robinson, Louis Harris, Margaret Gordon, Michael Thomas, Monsa Nitoto, Queen Thurston, and Robert Taylor) about their interactions with base, whether as a member of the military service, an employee of the Department of Defense, or as a resident of the nearby community of West Oakland.

The Civil Rights Movement is documented in our collection (though, admittedly, many more oral histories can be found elsewhere, such as at the Library of Congress), particularly as it

manifest in the San Francisco Bay Area in organizations that likely deserve more attention from researchers. Frances Mary Albrier was elected in the 1930s to the local Democratic Party Central Committee (and was welder during the war) and Terea Pittman became a leader of the NAACP (and many other organizations) in the earliest years of the Civil Rights Movement. The Council for Civic Unity, in addition, was established in the 1940s and was an important precursor to the California Fair Employment Practices Commission; Charles Patterson, in his interview, tells about the organization for which he was an intern before becoming a major figure in the foundation world (along with Ira DeVoyd Hall, who was a leader of the San Francisco Foundation). Orville Luster, who was interviewed in 1975, recalled his leadership of the unique Youth for Service organization which taught disadvantaged youth the skills necessary to be successful at work. And there is always a good deal of interest in the interview we hold with Ericka Huggins of the Black Panthers, which was donated to us by Fiona Thompson.

African Americans, not surprisingly, have played key roles in social justice work beyond the 1960s Civil Rights Movement. Henry Clark and Ahmadia Thomas and Carl Anthony were interviewed for their groundbreaking work in the area of environmental justice, while Michael Crawford and John Newsome were interviewed for our large project on Freedom to Marry, or the fight to win marriage equality. For our major project documenting the history of the Disability Rights and Independent Living Movements, we interviewed Chester Finn, Victor Robinson, and others.

Movement politics and protest is one way to force change, building institutions and running for elected office are other avenues pursued by African Americans we’ve interviewed over the years. I encourage you to read through two very interesting oral histories with three influential elected officials, Oakland Mayor Lionel Wilson and California State Assemblymen William Byron Rumford and Willie Brown (the second part of Brown’s oral history, covering his terms as San Francisco Mayor, will be released this spring). African Americans have made signal contributions to the law, as well: Cecil Poole, the first African American appointed as a United States Attorney in 1961, later became a distinguished federal judge; Allen Broussard rose up through the ranks of city and county courts, eventually joining the California State Supreme Court in 1981 as an associate justice; and to this day, US District Court Judge Thelton Henderson plays an outsized role in the area of law and civil rights.

Law and politics are only two venues in which an individual can make an impact as the ethos of public service runs through many other institutional domains. Born just over 120 years ago, C.L. Dellums led a life of public service through many offices, perhaps most notably as through his decades as Vice President and then President of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. After he had already done important work integrating the department, Robert Demmons was appointed the first African American Chief of the San Francisco Fire Department by Willie Brown in 1996. Everett Brandon might be little remembered today, but as a young man, he was a leader in San Francisco’s War on Poverty programs which brought services and employment to thousands of in the city. In recent decades, Joseph Marshall has continued the work of Brandon and others through his Omega Boys Club / Alive and Free service organization in San Francisco. The spirit of public service thrives in the private sector too. Our interviews with Ron Knox and Amanda Brown reveal how one of the largest private health care providers in the country have fought to improve health outcomes for African Americans.

The Oral History Center has long been committed to documenting our culture well beyond politics, law, and public service — we are deeply interested in the arts and the people who create them. Longtime OHC historian Caroline Crawford held an ongoing interest in documenting African American contributions to the arts, particularly music. Her interviews with Allen Smith (jazz trumpeter), Earl Watkins (jazz drummer), Gildo Mahones (jazz composer and pianist), John Handy (saxophonist, composer, and bandleader), and Jimmy McCracklin (blues singer and pianist).

Finally, I want to bring this back around to education, as this is the root of all good things (dare I say) and I think it is essential for a university to document its role in improving society and creating new possibilities. I very much encourage you to take a deep dive into the African American Faculty and Senior Staff project, perhaps beginning with a 20 minute video we produced a few years back. This project, however, was years in the making and while we refer to this group of early faculty and staff as “the Originals,” the truth is that they weren’t the first. Our interview with Archie Williams is a true hidden gem of the collection. Williams attended Berkeley between 1935 and 1939, which was punctuated by an appearance at the infamous 1936 Olympics in Berlin at which he won a gold medal. Although too old to serve in a combat role in World War II, as a certified pilot he trained the Tuskegee airmen! He went on to a career as a respected educator. Marvin Poston was a student at Berkeley at the same time as Williams and eventually became a widely respected optometrist. In 1958, Robert Gibson was the first African American to earn a doctorate in pharmacy at UCSF, where he became a distinguished member of the faculty. Born in 1920, Emmett Rice earned his doctorate in economics at Berkeley in 1954, before being named to the Federal Reserve Board of Governors in 1979; it is worth noting that Rice’s daughter is Susan Rice, who served as UN Ambassador and National Security Advisor in the Obama Administration. A graduate of UC Berkeley and San Diego State, Del Anderson Handy had a distinguished career in education, culminating with a term as chancellor of San Francisco City College.

These oral histories represent a meaningful slice of OHC’s interviews with African Americans, but surely not the entirety of the collection. The Oral History Center encourages you to not only explore the interviews listed above, but dig even deeper into our collection, honoring the voices of those African Americans we interviewed by reading their words and absorbing their ideas and experiences.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director

Find these interviews and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. You can also find the projects mentioned here on our projects page.