Tag: archives

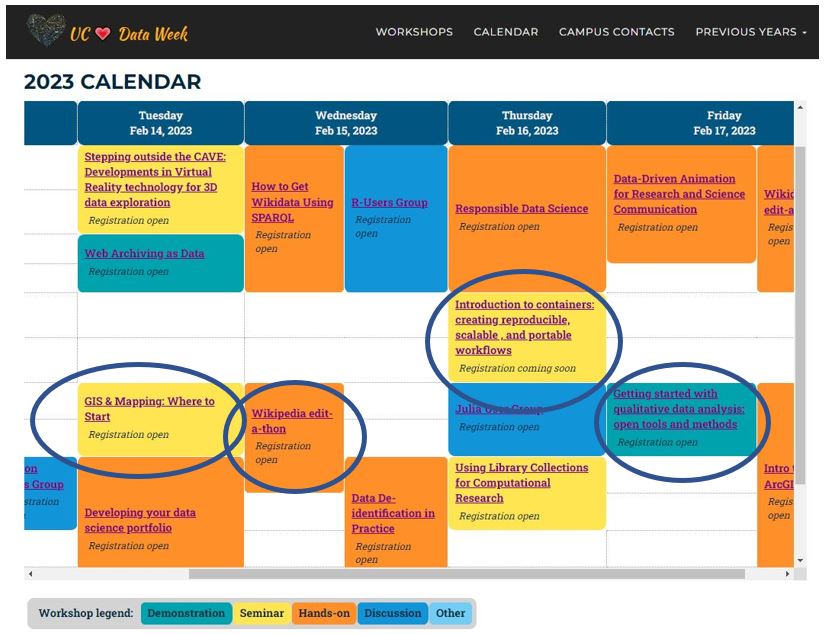

Coming Soon: Love Your Data, from Editathons to Containers!

UC Berkeley has been loving its data for a long time, and has been part of the international movement which is Love Data Week (LDW) since at least 2016, even during the pandemic! This year is no exception—the UC Berkeley Libraries and our campus partners are offering some fantastic workshops (four of which are led by our very own librarians) as part of the University of California-wide observance.

Love Data Week 2023 is happening next month, February 13-17 (it’s always during the week of Valentine’s Day)!

UC Berkeley Love Data Week offerings for 2023 include:

Wikipedia Edit-a-thon (you can also dip into Wikidata at other LDW events)

Textual Analysis with Archival Materials

Getting Started with Qualitative Data Analysis

All members of the UC community are welcome—we hope you will join us! Registration links for our offerings are above, and the full UC-wide calendar is here. If you are interested in learning more about what the library is doing with data, check out our new Data + Digital Scholarship Services page. And, feel free to email us at librarydataservices@berkeley.edu. Looking forward to data bonding next month!

Enhancing Searchability While Working From Home

As staff eagerly anticipate a return to more regular on-campus work, we have a guest posting by pictorial processing archivist Lori Hines. She provides a peek at one facet of work that we have been doing remotely in 2020-2021. -JAE

A posting by Lori Hines

Working from home during the COVID-19 closure has allowed Bancroft Library pictorial unit staff to enhance descriptions of digitized items, improving online searching.

One of my recent projects was to improve the description of items from the James D. Phelan Photograph Albums, BANC PIC 1932.001–ALB , which were scanned many years ago with only brief caption transcriptions. This photograph in album 85 is identified only as “Geneveve” [sic].

Having previously worked on collections related to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, I had an idea that Geneveve, or Genevieve, could be posed at a similar event. Currently the photo is essentially unidentified and lost in the sea of images.

A photo a few places earlier in the album was identified as “Crossing Columbia River,” so that gave a clue to a possible region. A photo a few spaces later had a date of 1909, so that gave a probable date.

Doing a quick Google check, I typed in “Exposition US 1909”, and voila, I easily confirmed that Geneveve must be at the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition held in Seattle. I then added “entrance” to the search, because there appear to be turnstiles behind the arches. Google image search gave me some pretty good matches. There was one image from the Seattle Municipal Archives that showed the turnstiles with part of the arch. A couple of other pictures had better views of the arch.

Now we have a useful identification for BANC PIC 1932.001 Vol. 85:296—ALB:

Once the improved finding aid data has been uploaded, the topic will be retrievable by keyword searching at both the Digital Collections website and the Online Archive of California.

Not all of the items get this depth of attention, but this is one example that is worth the extra time. It’s been difficult being away from collections and researchers for over a year, but there is no shortage of online content with minimal identification, so there’s gratification in taking this time to make improvements.

From the OHC Archives: Zona Roberts and Learning to Walk Backwards

by Annabelle Long

Annabelle Long is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center. She worked with Shanna Farrell during the Spring ’21 semester. Annabelle is a third-year History and Creative Writing student from Sacramento. She works as a conduct caseworker in the Student Advocate’s Office and enjoys going on long walks in Berkeley. You can find her on Twitter @annabelllekl.

The pocket of Berkeley bounded by Telegraph and Shattuck avenues is generally considered to be quiet and uneventful. Colorful Victorian houses line the blocks, gray apartment complexes full of Cal students loom over sidewalks, and telephone lines crisscross over each other, dividing the sky into irregularly sized rectangles and diamonds. I spend a lot of time in this part of Berkeley. I have my favorite houses, my favorite trees, my favorite views in every direction. I have my favorite alleys and blocks and moments in its history. I can’t pick a single favorite former resident, but Zona Roberts is high on the list.

Zona existed in Berkeley as a mother before she existed here as a student. She lived with her sons Ed, Ron, Mark, and Randy in a pale green house she rented on Ward Street, a few blocks west of the hustle and bustle of Telegraph Avenue and a few blocks east of Shattuck. I often walk by her old house. It’s blue now, with red front steps, and it sits unassumingly behind a fence overgrown with flowers in the springtime. When Zona moved in, she had a ramp installed in the back to allow Ed to get inside. Ed Roberts, Zona’s eldest son and a political science major at UC Berkeley, was the first wheelchair user ever admitted to the school, and virtually nothing in the city was wheelchair accessible when he arrived on campus in 1962, including his mother’s home.

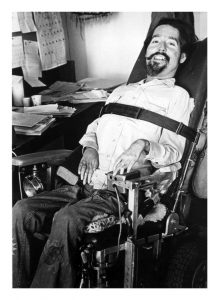

Ed Roberts

The green house, as it came to be known, acted as a sort of safe haven for the Roberts family and their friends. It was a family home for the community, not just Zona and her sons.

“It was a neighborhood of older families who’d lived there, a neighborhood of single-family homes, mostly, or two flats,” Zona said of the area, “The neighborhood was just changing as some of the older folks were dying off and some were moving away. A few younger people were moving in, but it was more or less an established neighborhood. But because of the racial composition and students in Berkeley, no one cared who went in and out of my house. The kids who came in or the Black students who visited and some lived, for a while, with me. There was no threat to their lives. There were none of those issues. It was just like a breath of fresh air to me. It was so nice not to have to worry about what might happen. I remember that vividly.”

Roberts Family

Zona, by all accounts, was an unflappable person. When she and her sons came to Berkeley, she was a recent widow, and had been Ed’s primary caretaker since he contracted polio and became a quadriplegic in 1953. She was a fierce advocate for all her sons and their needs and disliked being told what to do—she, as a learned expert in their likes and needs, felt that she knew best.

UC Berkeley promised a new world of opportunity for both her and Ed, when previously, his disability had meant neither of them was optimistic about what the future would hold, and her role as mother and caretaker left little room for imagining a life outside their home. But Berkeley was different; here, Ed was a student and leader, and eventually, so was she. In her oral history, when the conversation veered away from her time in Berkeley, she’d direct it back with references to the green house. The landscape of her college experience seemed to define it. She became acquainted with Berkeley alongside and behind Ed.

“One of the first days when I had taken Ed across and through campus, he was in a pushchair those days. He was quite tall and quite thin. We were going down into Faculty Glade and I had a hold of the back of his chair. It began to slip a little bit and I ran into a tree sort of deliberately to stop the chair, just the side of it, into this tree because I felt I was going to lose it. I don’t know whether my hands were sweaty, or the place was wet or what was happening. I think I finally learned how to do it backwards, where I’d walk down the hill backwards. I had better control.”

This anecdote, in my mind, speaks to the essence of Zona Roberts: ever present and adaptable to the needs of her son, caring and thoughtful, in the heart of Berkeley.

“In my senior year, I’d visit Ed up at Cowell. I remember one of the first times I walked through campus carrying my books, walked by Strawberry Creek, walking up to Cowell instead of coming in the station wagon from home or coming over to visit them. Here I was walking across campus on my way between classes and going up to visit and smiling a broad smile that I was now a student at Berkeley, also, and very proud of myself, and loving the campus and Strawberry Creek coming down through the middle of it. There’s some beauty in that Berkeley campus,” she said.

This feeling of reverence for Berkeley—for the atmosphere of casual intellectualism, for the exciting possibilities of being a student, for the sometimes-unbelievable natural beauty of the campus—is one I am intimately familiar with. I can only imagine how those feelings would be magnified for Zona, who, as a middle-aged widow and mother of four, never thought she’d live in Berkeley or become a student.

Zona was immensely proud to be a Berkeley student and to be Ed’s mother. She encouraged his involvement in activism and saw herself as an important backer of the disability rights movement; she saw herself as, first and foremost, an important backer of Ed.

“I saw my role at the office [UC Berkeley’s Center for Independent Living] as it became known as I did in Ed’s life, pushing Ed in front and being behind him,” she said of her involvement, “This was a place for people with visible disabilities to be visible, to be out in front. I found myself being in a supporting role, seeing that the office functions were going as smoothly as possible, seeing that there was food and heat and counseling and open doors and open access to information from us to the university and from the university to us. But somehow, we were in this together and it was a part of a wonderful movement. The time had come, and we were in the forefront of the movement and we were told this from all over the world. That was a glorious feeling. Hard work and glorious feeling.”

Zona Roberts

Zona Roberts worked hard to be the best mother she could be. Eventually, that meant becoming an integral part of a movement that was so much larger than any of them individually. If Ed Roberts was the father of the disability rights movement, Zona was the grandmother. She worked in the Center for Independent Living for years after its founding, and remains active in disability rights activism today, years after Ed’s death and well into her one hundred and first year of life.

I imagine the learning process of her activism was similar to learning to walk down the hill next to the Faculty Glade backwards, or modifying the old green house on Ward Street to make it accessible: sometimes slow-going, and certainly not without error, but always more than worth the trouble.

Crip Camp and Judy Heumann: Studies in Movement Snapshots

by Annabelle Long

Annabelle Long is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center. She worked with Shanna Farrell during the Spring ’21 semester. Annabelle is a third-year History and Creative Writing student from Sacramento. She works as a conduct caseworker in the Student Advocate’s Office and enjoys going on long walks in Berkeley. You can find her on Twitter @annabelllekl.

I watched the 2020 documentary Crip Camp to get a sense of Judy Heumann, the disability rights icon and architect of a movement that created a more accessible world. I had only recently read her oral history, conducted by UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center, and I was eager to learn more about the woman behind the words on the page. When she is first shown in the film, she is doing what I’ve learned that she does best: leading a group. She has a big voice and a bigger grin, and talks campers through their options for dinner later in the week. She’s already thought it through—she considered veal parmesan, but found the veal to be too expensive, so next on her list is lasagna, the suggestion of which elicits both cheers and groans from the crowd. She offers everyone a chance to make their case, and then takes a vote. Lasagna wins—barely. This vote, in its consequences, probably meant very little to Judy and very little to everyone else. But in my mind, it makes one thing clear: Judy didn’t make any decisions without considering and consulting the group. She cared what people had to say, and she listened. And so campers had lasagna, and eventually, thanks to her activism, disabled Americans had laws to protect them.

Crimp Camp provides a snapshot of the disability rights movement through the lens of Camp Jened, a summer camp for disabled children and teenagers that opened in upstate New York in 1951. Each summer, about 120 campers moved in for four to eight weeks. The camp, despite often being credited with changing the lives of its campers, had immense financial struggles and closed its doors in 1977, leaving its legacy in the hands of the many campers who passed through. Judy contracted polio and became paralyzed at 18 months old, and for every summer from ages 9 to 18, she was one of those campers. She credited her time at Jened with shaping her approach to activism and life generally.

Jened resembles the woodsy summer camps of my childhood, but it had more of a Summer of Love aura about it—the rec room was boisterous and the softball games were passionately played, but at Jened, counselors were hippies, campers fell in love, and the bunkrooms and mess halls overflowed with eager conversations about the state of disability rights and the world. It was in those conversations, Judy would go on to say, that she learned to listen to a group, lead a group, and speak as a part of a group. To Judy and the other campers, Jened was more than a camp: it was a place to be fully and truly oneself, a place to try out new politics, and often, a place to meet close friends and lovers (Judy even said she never dated outside of camp). It almost seemed sacred.

Jened is both a moment and an enduring feature in the history of the disability rights movement, and Crip Camp seeks to understand it as both: as a physical place, where people gathered and grew, and as a concept, a memory and idea that endured well beyond the summers it operated. Oral history, as a practice, seeks to accomplish something similar. It draws on memories of particular moments, the feelings that make something worth remembering, and unites those memories with broader historical narratives to give a complete picture of a life and a time. But I can’t help but wonder—what does it mean when a story continues after the taping is done? When the end of the recorded narrative turns out to be the midpoint of a real and full life?

Judy Heumann’s oral history focuses on her time UC Berkeley, where she received her master’s in Public Health, and the 504 sit-in of 1977, which she was critical in organizing. For 25 days, Judy and well over 100 disabled people occupied the San Francisco office of the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare and demanded enforcement of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which stated that no institution receiving federal funding could exclude people on the basis of their disability. Judy’s activism in 1972 was critical to getting Section 504 written in the first place, and she and other disabled people were tired of it being completely unenforced—schools, cities, and buildings were still inaccessible despite the law’s promise. Schools lacked elevators to allow disabled students to get to their classrooms; sidewalks lacked defined dips in the corners and thus often forced wheelchair users to take inconvenient, circuitous routes to their destinations or left them stranded. In response, disabled people occupied government buildings across the country in protest. The San Francisco demonstration was the longest lasting and arguably the most successful, largely thanks to the motivating force that was Judy Heumann.

Judy Heumann

In Crip Camp, Corbett O’Toole, a disabled activist and one of Judy’s contemporaries at the Center for Independent Living at UC Berkeley, said that “we were more scared of disappointing Judy Heumann than we ever were of the FBI or police department arresting us.” This was because Judy served as the central organizing force of the occupation—she held down the fort, ensured people’s needs were met (no easy task when many occupiers required around-the-clock physical assistance), and negotiated with government figures to advance the cause. I’d be scared to disappoint her, too.

There’s no debate about her status as an organizing powerhouse. In the early days of the disability rights movement, everyone in her orbit seemed to recognize that she had a knack for getting people together, getting people to listen, and perhaps most crucially, getting people to act. Mary Lester, a staff member at the Center for Independent Living spoke about Judy in her own oral history and credited her with the movement’s expansion.

“Judy was the one who brought in deaf services and was the one who always wanted to expand the population we were serving. She was pushing us in those directions to broaden the coalition. She was a networker supreme,” she said, “Judy wanted to push CIL as far as it could go in terms of being a model and being a pioneer and bringing all of the different disability factions, if you will, together.”

Judy was meticulous and thoughtful in her activism; no stone went unturned, no idea went unexplored, and no voice went unheard.

“We had the civil rights aura, but we had the facts,” she said of the Independent Living Movement, which she helped develop in Berkeley, “I mean, I think the civil rights aura without the facts actually doesn’t get you where you need to be. But the facts without the civil rights perspective doesn’t necessarily get you there either.”

Berkeley, as a city and community center, played a critical role in shaping the 504 sit-ins and the disability rights movement more broadly.

“Well, you know Berkeley is a small community, period. And many of the people certainly at that time were activists. And you lived on the same block with somebody, or a couple of blocks away,” she said, starting to laugh, “And that’s just the way it is. It’s a town.”

UC Berkeley was to Judy and her friends what Jened had been to them in their youth. Crip Camp gets at this: many of Judy’s friends from her camp days eventually made the same westward journey that she did, and ended up in and around the UC Berkeley community. There, they took the community they’d built in upstate New York and turned to activism. Jened taught them the importance of their community; Berkeley taught them how to fight for it.

Judy Heumann recorded her oral history with UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center in 2007, decades after her time at Camp Jened and some of her most well-known organizing efforts. Since then, she’s lived nearly another decade and a half—enough time to feature in an Oscar-nominated documentary, host a podcast, produce a research paper on improving media representation of disabled people, publish a memoir, and work on advancing disability rights internationally as a special advisor to President Obama in the State Department.

She spoke about her international ambitions and hopes for the disability rights movement in her oral history, before Barack Obama was even the Democratic nominee for president; before there was even an inkling that her role as his special advisor on international disability rights would ever exist. In this way, oral history provides us with a window into her mind, a snapshot of a moment in the unfinished history of the disability rights movement. This, perhaps, is part of the value of an oral history conducted before the end of someone’s life—it reveals the in the moment motivations and thoughts behind future actions, and is definitionally more than just temporally distanced reflection or speculation about how and why something occurred.

Judy Heumann at the 2021 Academy Awards

In the same way that Crip Camp sought to capture multiple dimensions of Camp Jened and its legacy, looking at Judy Heumann’s oral history in light of the more recent years of her life allows for a complex and interesting portrait of her and her accomplishments. As a history major, the people I study often never lived to see the worlds that they created, so it is especially wonderful to know that Judy Heumann saw the disability rights movement from its inception to a piece of storied history behind the world as we know it now.

“But you know, you walk up Telegraph Avenue, you go to Rasputin’s, and you see this history of the disability movement, and the owner of the store proudly displaying history of the disability rights movement on a building,” she said in her oral history, “You see, I go into a restaurant yesterday and there are two young disabled people coming in from Berkeley sitting down and having lunch together. The waiter’s moving the chairs out, and I’m like, oh, I guess two people in chairs are coming. And these things are natural now, because there is such a large number of people here that the community itself has become more accepting. It’s normal.”

I am a student at UC Berkeley and I live a block from Telegraph Avenue; between me and Judy’s tangible legacy sits a sidewalk that slopes down at the corners for wheelchair access. The world is not perfectly accessible, and there is still much to be done to ensure that disabled people’s rights are protected, but I like to think about how my normal is the product of Judy’s life’s work.

From the OHC Archives: Linda Perotti, Apolitical Advocate

By Annabelle Long

Annabelle Long is an Undergraduate Research Apprentice at the Oral History Center. She worked with Shanna Farrell during the Spring ’21 semester. Annabelle is a third-year History and Creative Writing student from Sacramento. She works as a conduct caseworker in the Student Advocate’s Office and enjoys going on long walks in Berkeley. You can find her on Twitter @annabelllekl.

Linda Perotti didn’t mean to join a movement. She arrived in Berkeley a year after the Free Speech Movement got its raucous start on the steps of Sproul Hall, the university’s now-famous administrative building on the southern edge of campus, and she was more concerned with keeping up with her coursework than with any of the growing number of antiwar and civil rights movements that would come to characterize Berkeley in the late 60s.

“[T]he thing I remember most is the Sproul steps, just sitting there and watching people go by,” she said of her freshman year. She regarded herself as an observer, never a participant. But as these things tend to happen, a movement found Linda anyway.

As a freshman at Cal, Linda was surrounded by the energy of the movements unfolding across campus. Sproul Plaza seemed perpetually occupied by someone giving an impassioned speech about any number of political issues to a crowd of eager students, her male friends constantly fretted about being drafted, and sometimes, police vans and teargas would descend on campus, their motivations largely unbeknownst to her. On any given day, her Sproul people-watching might have included a lecture on the value of political speech on college campuses, a demonstration against the Vietnam War, or a march down Telegraph Avenue, which led from campus into the city. UC Berkeley, to her, was a thrilling, semi-utopic reprieve from a culturally homogenous childhood spent in Michigan and the San Fernando Valley; a place where everyone and everything could be reached on foot; a place where she could be an individual; a place where everyone was intellectually serious, but no one took themselves too seriously.

Sproul Plaza during the Free Speech Movement

Linda remained uninvolved in campus politics for her first two years at Cal, but that doesn’t mean she wasn’t paying attention to things happening around her.

“I remember one of the eeriest sights, when I really became aware of what a political hotbed Berkeley was,” she said of witnessing a stand-off outside her freshman dorm, just south of campus, “What turned out to be a SWAT team. They were all cops, just gathering, with shields and helmets and batons. I had never seen anything like that. It was extremely scary. Now if you saw that, you might just shrug and say, ‘Oh, something’s going on.’ But in 1965, it was a real phenomenon.” She didn’t have to be involved in a movement to understand that they were everywhere in Berkeley.

She moved to a new apartment on Ward Street at the beginning of the summer of ‘68—the summer of Robert Kennedy’s assassination, the Poor People’s Campaign, and Nixon’s nomination—and soon found herself spending a lot of time with the Roberts family, whose comings and goings via van and motorcycle she’d observed for weeks before discovering that one of the motorcyclists was her acquaintance, Mark Roberts. The small, green Roberts house was a peculiar one for a college town, and Linda was drawn to the fact that the Roberts family actually acted as a family unit. Linda had many friends, but they were just as independent as she; she didn’t yet have a family in Berkeley.

Zona Roberts and her sons were different. Zona zipped off to class on her motorcycle each morning, and there seemed to be a constant rotation of young people cycling in and out of the house.

“The whole family—they’re a very friendly family. Very, very friendly people. And just very unassuming. At the time, Zona was a student at Berkeley herself. Her husband had died a few years earlier. I don’t know how she did it financially. She was always on the edge, but somehow she managed,” Linda recalled.

She was attracted to the hum of energy radiating from the house and soon befriended Mark’s older brother Ed Roberts, the first wheelchair user admitted to UC Berkeley and the eventual father of the Disability Rights and Independent Living Movement. He suggested that she stop by Cowell Hospital and lend a hand. Cowell, while a fully functioning campus infirmary, also functioned as a dormitory of sorts for physically disabled students. It was unlike any program that existed anywhere else, and while Linda’s recollection of her early days there was hazy, she spent her summer on the northwest side of campus, doing odd jobs at Cowell.

Cowell Hospital

As a woman, the help she could offer was limited—only men lived in Cowell at that point, and she recalled that “the men only had other young men working for them,” so she found herself doing laundry, typing up various documents, pushing wheelchair users around campus, and hauling enormous pots of chili and spaghetti across campus for Friday night dinners. Gender continued to define Linda’s relationship to Cowell and the budding Disability Rights Movement writ large; to her, the politics of the movement were for the boys.

“I never was interested in the political aspects of it,” she said, “It was just a byproduct as far as I was concerned. I even used to laugh at the guys. See, ‘the guys.’ It just happened to be that way.”

This disinterest was not from lack of care, but rather what Linda described as a naturally apolitical disposition. It wasn’t as if she wasn’t also interested in the pro-disability rights causes “the guys” were organizing for; of course she was. She spent her days working at Cowell and with the leaders of the Disability Rights Movement, albeit never in the context of their activism.

“This was really good for me,” she said of her proximity to their activism, “because it suited my level of political interest or awareness.” To Linda, her work was most significant when it was on the ground and person-to-person. Someone else could handle writing to the Chancellor.

“I had gone through the Cowell Hospital movement where people got organized and found their own strength and actually made their demands in such a way that the university responded to them and actually established a program just to serve the physically disabled,” she recalled, “That was very interesting.”

In the fall of 1968, the Cowell Program admitted its first female resident, and just as he had earlier in the summer, Ed Roberts encouraged Linda to go on up and introduce herself. Perhaps, Ed thought, Linda could serve as this new resident’s attendant, and help her with day-to-day tasks like bathing and getting dressed for class. Cathy Caulfield, Cowell’s first female resident, arrived in time for the fall semester, and sure enough, Linda became one of her attendants. At the same time, Linda recalled, the conversations that would serve as the foundation of the disability rights movement started picking up on the third floor of Cowell, where the program residents lived. Something was in the air.

But Linda was focused on her work. She had never been an attendant before, and the job was demanding. She deeply cared about being a good attendant for Cathy, and even beyond that, she cared about being a friend to her. So Cathy taught her how to change a urinary catheter, and how to dress and bathe her, and in turn, Linda learned how to be caring and gentle and composed. Her experience was typical; none of the attendants had formal training beyond what the people they worked for taught them. Cathy soon became deeply involved in the political organizing happening on the third floor, and she and Linda became good friends.

“I didn’t see myself as part of an attendant group because the rest were guys, and they worked for the guys, and my two friends and I worked for Cathy, ‘the woman,’” Linda said, referring to her two close friends who also worked as attendants. Her focus was Cathy, not finding community with other attendants or Cowell residents, and to her, that was just as well.

The next few years of Linda’s life track nicely alongside the development of the Disabled Students’ Program (DSP) and the Center for Independent Living (CIL)—she stopped taking classes during what would have been her senior year, and spent a lot of time with the organizers behind DSP and CIL as the programs swelled in size and scope. Still, though, movement politics were uninteresting to her. She cared about streamlining attendant referral services—everything was still word of mouth—and developing peer counseling services for disabled students, and helping the organizers accomplish other goals that they had, but she understood her role to be primarily administrative.

Linda Perotti never thought of herself as an activist. Her work was work, even if that work was also groundbreaking and life-changing and empowering for more people than she ever probably knew she could reach. The Sproul steps that she remembered so fondly have since witnessed many more movements, and many more generations of students who have benefitted from the activism—and semi-passive support—of Berkeley students that came before them. Linda may not have meant to join a movement, and maybe she would contend that she never actually did, but she certainly made a difference—for Cathy and the other Cowell residents, for herself, and for the generations of Berkeley students that followed her.

New Project Release: Marion and Herb Sandler Oral History Project

New Project Release: Marion and Herb Sandler Oral History Project

Herb Sandler and Marion Osher Sandler formed one of the most remarkable partnerships in the histories of American business and philanthropy—and, if their friends and associates would have a say in things, in the living memory of marriage writ large. This oral history project documents the lives of Herb and Marion Sandler through their shared pursuits in raising a family, serving as co-CEOs for the savings and loan Golden West Financial, and establishing a remarkably influential philanthropy in the Sandler Foundation. This project consists of eighteen unique oral history interviews, at the center of which is a 24-hour life history interview with Herb Sandler.

Marion Osher Sandler was born October 17, 1930, in Biddeford, Maine, to Samuel and Leah Osher. She was the youngest of five children; all of her siblings were brothers and all went on to distinguished careers in medicine and business. She attended Wellesley as an undergraduate where she was elected into Phi Beta Kappa. Her first postgraduate job was as an assistant buyer with Bloomingdale’s in Manhattan, but she left in pursuit of more lofty goals. She took a job on Wall Street, in the process becoming only the second woman on Wall Street to hold a non-clerical position. She started with Dominick & Dominick in its executive training program and then moved to Oppenheimer and Company where she worked as a highly respected analyst. While building an impressive career on Wall Street, she earned her MBA at New York University.

Herb Sandler was born on November 16, 1931 in New York City. He was the second of two children and remained very close to his brother, Leonard, throughout his life. He grew up in subsidized housing in Manhattan’s Lower East Side neighborhood of Two Bridges. Both his father and brother were attorneys (and both were judges too), so after graduating from City College, he went for his law degree at Columbia. He practiced law both in private practice and for the Waterfront Commission of New York Harbor where he worked on organized crime cases. While still living with his parents at Knickerbocker Village, he engaged in community development work with the local settlement house network, Two Bridges Neighborhood Council. At Two Bridges he was exposed to the work of Episcopal Bishop Bill Wendt, who inspired his burgeoning commitment to social justice.

Given their long and successful careers in business, philanthropy, and marriage, Herb and Marion’s story of how they met has taken on somewhat mythic proportions. Many people interviewed for this project tell the story. Even if the facts don’t all align in these stories, one central feature is shared by all: Marion was a force of nature, self-confident, smart, and, in Herb’s words, “sweet, without pretentions.” Herb, however, always thought of himself as unremarkable, just one of the guys. So when he first met Marion, he wasn’t prepared for this special woman to be actually interested in dating him. The courtship happened reasonably quickly despite some personal issues that needed to be addressed (which Herb discusses in his interview) and introducing one another to their respective families (but, as Herb notes, not to seek approval!).

Within a few years of marriage, Marion was bumping up against the glass ceiling on Wall Street, recognizing that she would not be making partner status any time soon. While working as an analyst, however, she learned that great opportunity for profit existed in the savings and loan sector, which was filled with bloat and inefficiency as well as lack of financial sophistication and incompetence among the executives. They decided to find an investment opportunity in California and, with the help of Marion’s brothers (especially Barney Osher), purchased a tiny two-branch thrift in Oakland, California: Golden West Savings and Loan.

Golden West—which later operated under the retail brand of World Savings—grew by leaps and bounds, in part through acquisition of many regional thrifts and in part through astute research leading to organic expansion into new geographic areas. The remarkable history of Golden West is revealed in great detail in many of the interviews in this project, but most particularly in the interviews with Herb Sandler, Steve Daetz, Russ Kettell, and Mike Roster, all of whom worked at the institution. The savings and loan was marked by key attributes during the forty-three years in which it was run by the Sandlers. Perhaps most important among these is the fact that over that period of time the company was profitable all but two years. This is even more remarkable when considering just how volatile banking was in that era, for there were liquidity crises, deregulation schemes, skyrocketing interest rates, financial recessions, housing recessions, and the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s, in which the entire sector was nearly obliterated through risky or foolish decisions made by Congress, regulators, and managements. Through all of this, however, Golden West delivered consistent returns to their investors. Indeed, the average annual growth in earnings per share over 40 years was 19 percent, a figure that made Golden West second only to Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, and the second best record in American corporate history.

Golden West is also remembered for making loans to communities that had been subject to racially and economically restrictive redlining practices. Thus, the Sandlers played a role in opening up the dream of home ownership to more Americans. In the offices too, Herb and Marion made a point of opening positions to women, such as branch manager and loan officer, previously held only by men. And, by the mid-1990s, Golden West began appointing more women and people of color to its board of directors, which already was presided over by Marion Sandler, one of the longest-serving female CEOs of a major company in American history. The Sandlers sold Golden West to Wachovia in 2006. The interviews tell the story of the sale, but at least one major reason for the decision was the fact that the Sandlers were spending a greater percentage of their time in philanthropic work.

One of the first real forays by the Sandlers into philanthropic work came in the wake of the passing of Herb’s brother Leonard in 1988. Herb recalls his brother with great respect and fondness and the historical record shows him to be a just and principled attorney and jurist. Leonard was dedicated to human rights, so after his passing, the Sandlers created a fellowship in his honor at Human Rights Watch. After this, the Sandlers giving grew rapidly in their areas of greatest interest: human rights, civil rights, and medical research. They stepped up to become major donors to Human Rights Watch and, after the arrival of Anthony Romero in 2001, to the American Civil Liberties Union.

The Sandlers’ sponsorship of medical research demonstrates their unique, creative, entrepreneurial, and sometimes controversial approach to philanthropic work. With the American Asthma Foundation, which they founded, the goal was to disrupt existing research patterns and to interest scientists beyond the narrow confines of pulmonology to investigate the disease and to produce new basic research about it. Check out the interview with Bill Seaman for more on this initiative. The Program for Breakthrough Biomedical Research at the University of California, San Francisco likewise seeks out highly-qualified researchers who are willing to engage in high-risk research projects. The interview with program director Keith Yamamoto highlights the impacts and the future promise of the research supported by the Sandlers. The Sandler Fellows program at UCSF selects recent graduate school graduates of unusual promise and provides them with a great deal of independence to pursue their own research agenda, rather than serve as assistants in established labs. Joe DeRisi was one of the first Sandler Fellows and, in his interview, he describes the remarkable work he has accomplished while at UCSF as a fellow and, now, as faculty member who heads his own esteemed lab.

The list of projects, programs, and agencies either supported or started by the Sandlers runs too long to list here, but at least two are worth mentioning for these endeavors have produced impacts wide and far: the Center for American Progress and ProPublica. The Center for American Progress had its origins in Herb Sandler’s recognition that there was a need for a liberal policy think tank that could compete in the marketplace of ideas with groups such as the conservative Heritage Foundation and the American Enterprise Institute. The Sandlers researched existing groups and met with many well-connected and highly capable individuals until they forged a partnership with John Podesta, who had served as chief of staff under President Bill Clinton. The Center for American Progress has since grown by leaps and bounds and is now recognized for being just what it set out to be.

The same is also true with ProPublica. The Sandlers had noticed the decline of traditional print journalism in the wake of the internet and lamented what this meant for the state of investigative journalism, which typically requires a meaningful investment of time and money. After spending much time doing due diligence—another Sandler hallmark—and meeting with key players, including Paul Steiger of the Wall Street Journal, they took the leap and established a not-for-profit investigative journalism outfit, which they named ProPublica. ProPublica not only has won several Pulitzer Prizes, it has played a critical role in supporting our democratic institutions by holding leaders accountable to the public. Moreover, the Sandler Foundation is now a minority sponsor of the work of ProPublica, meaning that others have recognized the value of this organization and stepped forward to ensure its continued success. Herb Sandler’s interview as well as several other interviews describe many of the other initiatives created and/or supported by the foundation, including: the Center for Responsible Lending, Oceana, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Learning Policy Institute, and more.

Herb and Marion Sandler also played key roles in the formation and funding of two important research centers here on the UC Berkeley campus which have a global reach: the Berkeley Center for Equitable Growth (CEG) and the Human Rights Center. The CEG is directed by economist Emmanual Saez and has supported the influential work of Thomas Piketty which looks at methods for reducing wealth and income disparities around the globe. The Human Rights Center has for the past 25 years investigated and shed light upon human rights abuses around the globe.

A few interviewees shared the idea that when it comes to Herb and Marion Sandler there are actually three people involved: Marion Sandler, Herb Sandler, and “Herb and Marion.” The later creation is a kind of mind-meld between the two which was capable of expressing opinions, making decisions, and forging a united front in the ambitious projects that they accomplished. I think this makes great sense because I find it difficult to fathom that two individuals alone could do what they did. Because Marion Sandler passed away in 2012, I was not able to interview her, but I am confident in my belief that a very large part of her survives in Herb’s love of “Herb and Marion,” which he summons when it is time to make important decisions. And let us not forget that in the midst of all of this work they raised two accomplished children, each of whom make important contributions to the foundation and beyond. Moreover, the Sandlers have developed many meaningful friendships (see the interviews with Tom Laqueur and Ronnie Caplane), some of which have spanned the decades.

The eighteen interviews of the Herb and Marion Sandler oral history project, then, are several projects in one. It is a personal, life history of a remarkable woman and her mate and life partner; it is a substantive history of banking and of the fate of the savings and loan institution in the United States; and it is an examination of the current world of high-stakes philanthropy in our country at a time when the desire to do good has never been more needed and the importance of doing that job skillfully never more necessary.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director, Oral History Center, UC Berkeley

List of Interviews of the Marion and Herbert Sandler Oral History Project

Ronnie Caplane, “Ronnie Caplane: On Friendship with Marion and Herb.”

Joseph DeRisi, “Joe DeRisi: From Sandler Fellow to UCSF Professor of Biochemistry.”

Stephen Hauser, “Stephen Hauser: Establishing the Sandler Neurosciences Center at UCSF.”

Russell Kettell, “Russ Kettell: A Career with Golden West Financial.”

Thomas Laqueur, “Tom Laqueur: On the Meaning of Friendship.”

Bernard Osher, “Barney Osher: On Marion Osher Sandler.”

Michael Roster, “Michael Roster: Attorney and Golden West Financial General Counsel.”

Kenneth Roth, “Kenneth Roth: Human Rights Watch and Achieving Global Impact.”

Herbert Sandler, “Herbert Sandler: A Life with Marion Osher Sandler in Business and Philanthropy.”

James Sandler, “Jim Sandler: Commitment to the Environment in the Sandler Foundation.”

Susan Sandler, “Susan Sandler: The Sandler Family and Philanthropy.”

William Seaman, “Bill Seaman: The American Asthma Foundation.”

Paul Steiger, “Paul Steiger: Business Reporting and the Creation of ProPublica.”

Richard Tofel, “Richard Tofel: The Creation and Expansion of ProPublica.”

Thérèse Bonney: Art Collector, Photojournalist, Francophile, Cheese Lover

Thérèse Bonney aboard the S.S. Siboney, en route to Portugal, 1941. BANC PIC 1982.111 series 3, NNEG box 49, item 19

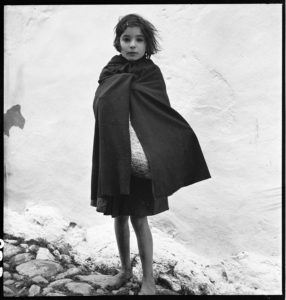

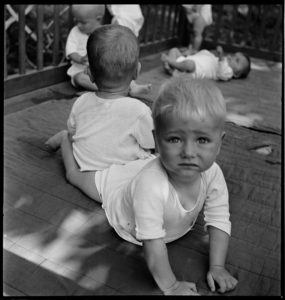

Pioneering war correspondent and Cal grad Mabel Thérèse Bonney (1894-1978) was decorated with the Croix de Guerre and the Legion d’Honneur by the French government, and the Order of the White Rose of Finland for her work during World War II. Her photographs were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, the Library of Congress, and Carnegie Hall during her lifetime. Her work on children displaced by war spurred the United Nations to create their international children’s emergency fund, UNICEF, in 1946, and inspired the Academy Award-winning film The Search in 1948. Yet in the canon of female war photographers that includes contemporaries such as Lee Miller, Margaret Bourke-White, and Toni Frissell, Bonney rarely receives mention. Bonney was a renaissance woman whose life deserves further study, and her collections at the Bancroft Library are ripe for discovery. Manuscript Archivist Marjorie Bryer has processed The Thérèse Bonney papers, and Pictorial Archivist Sara Ferguson has digitized over 2,500 previously inaccessible nitrate negatives from the Thérèse Bonney Photograph Collection.

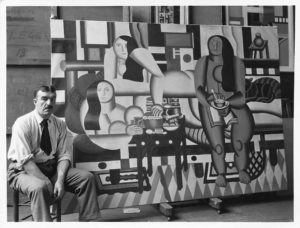

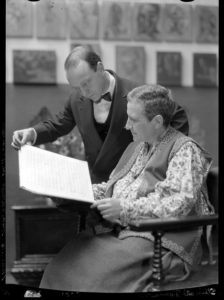

ART CONNOISSEUR

While living in Paris in the 1920s and 1930s, Bonney modeled for fashion designers like Sonia Delaunay and Madeleine Vionnet, and became friends with many of the most famous artists and writers of her day, including Raoul Dufy, Gertrude Stein, and George Bernard Shaw. In 1924 Bonney founded an international photo service that licensed images acquired in France for publication in the U.S. She was often dissatisfied with the images she distributed, and this inspired her to take up photography herself. Bonney wrote about, and took photographs of, many of the artists and writers in her life throughout the twenties, thirties, and forties.

PHOTOJOURNALISM AND WAR RELIEF EFFORTS

Bonney photographed throughout Europe during World War II, focusing on the effects of war on the civilian population. Her photographs of children were particularly moving and resulted in her most famous work, the exhibit and book, Europe’s Children. Bonney was actively involved with relief efforts after the war, particularly in the Alsace region of France. She also founded a number of organizations dedicated to promoting friendship between citizens of France and the United States, and improving Franco-American political relations. One effort, the Chain d’Amite, encouraged French families to open their homes to American G.I.s; another, Project Patriotism, inspired airmen who were shot down in France to help the families that had rescued them. Project Patriotism eventually spread to other European countries, including the Netherlands. Marjorie’s father-in-law, Peter, was a teenager when Germany invaded the Netherlands during the war. He was sent to live with relatives in the Dutch countryside so he wouldn’t be conscripted. One of Peter’s most moving stories was about the American pilot his family hid when his plane crashed on the family farm. Bonney’s papers include many poignant letters from U.S. soldiers and, while processing the collection, Marjorie wondered what this airman from Brooklyn might have written about his experiences with his Dutch “family.”

LOVER OF CHEESE

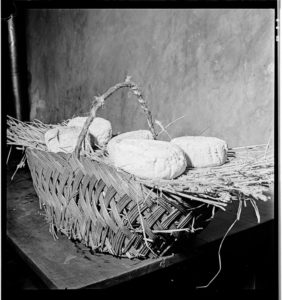

Bonney’s many interests included food and cooking. She and her sister, Louise, wrote a guide to Paris restaurants and a cookbook, French cooking for American kitchens. Her papers include her research on cheese, which she referred to as “Project Fromage.” Series 7 of Bonney’s papers include meticulous notes on various cheeses from France and the Netherlands, “technical” correspondence about cheese, and materials related to tyrosemiophilia — the hobby of collecting cheese labels.

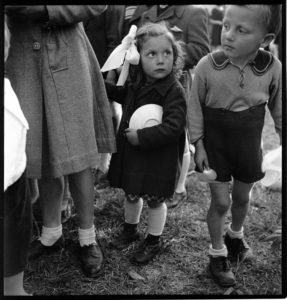

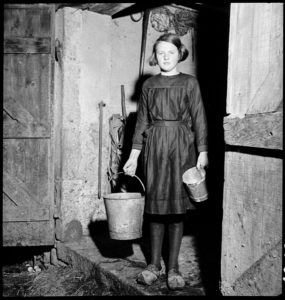

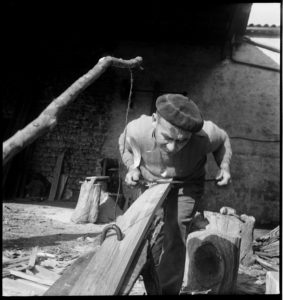

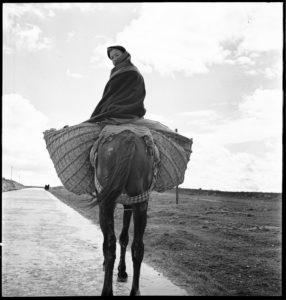

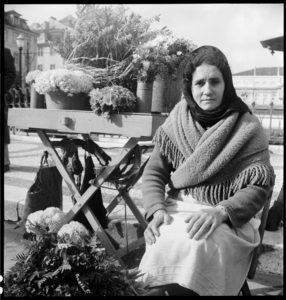

EVERYDAY PEOPLE AND LIFE DURING WARTIME

Bonney documented daily life during wartime across Europe. She recorded entire communities — their families, customs, and industries, their artists and politicians, their schools, and their churches. Her papers and photographs show not only the horrors of war but the hope and perseverance of those who lived through it.

NOW AVAILABLE AT THE BANCROFT LIBRARY!

Newly digitized portions of the pictorial collection include Series 6: France, Germany 1944-1946. This series includes photographs of concentration camps Vaihingen, Buchenwald, and Dachau; Displaced Person camps; Neuschwanstein Castle; and Hermann Göring’s Collection of art looted by the Nazi’s. It also includes many images of the heavily bombarded town of Ammerschwihr in Alsace, France and war relief efforts there. Future digitization efforts will focus on Series 3, Carnegie Corporation Trip: Portugal, Spain, France 1941-1942. This series consists of images taken while on a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York to document the effects of war on civilian populations. It includes images of military personnel, civilian industries, and Red Cross operations. Famous personalities pictured in this series include Pierre Bonnard, Henri Matisse, Georges Roualt, Gertrude Stein, Philippe Petain, Raoul Dufy, and Aristide Maillol.

Bonney’s papers help contextualize her photographs. They include correspondence; personal materials; her writings (autobiographical and articles about others); and her files on World War II, Franco-American relations, art, fashion, photography, and cheese.

Both collections are open for research:

Finding Aid to the Thérèse Bonney Photograph Collection, circa 1850-circa 1955 (bulk 1930-1945)

Finding Aid to the Thérèse Bonney Papers

— Marjorie Bryer and Sara Ferguson

From the Archives: Staff Picks

This month, we’re bringing you a special edition of our From the Archives department. Below are interviews, all available in the OHC archives, recommended by each of us. Enjoy digging through the crates!

Martin Meeker’s pick:

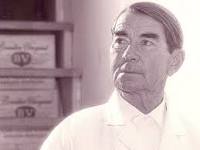

Andre Tchelistcheff: Grapes, Wine, and Technology. Some lives in our collection of interviews are just profoundly interesting, and well worth digging into. This might be because of difficulties surmounted, achievements recognized, or simply the quality of the telling. Our 1979 oral history with Andre Tchelistcheff reveals one such life that ticks all of those boxes. From his birth in Russia in 1901, through his harrowing escape during the Revolution, to his years in France studying viticulture, and his decades quite literally remaking California’s wine industry, Tchelistcheff lived a remarkably influential life while remaining rooted in his passions throughout.

Roger Eardley-Pryor’s pick:

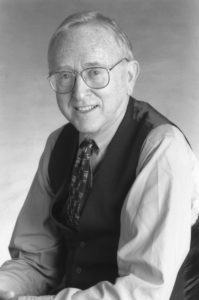

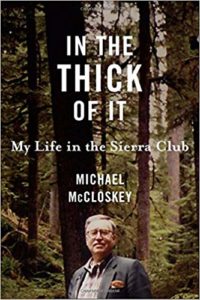

J. Michael McCloskey (Mike McCloskey), “Sierra Club Executive Director and Chairman, 1980s-1990s: A Perspective on Transitions in the Club and the Environmental Movement,” conducted in 1998 and published in 1999, is the second oral history with Mike McCloskey as part of the Sierra Club Oral History Project. Mike, a longtime leader in one of the largest environmental organizations in the United States, discusses the Club’s growing pains associated with an upsurge in membership amid Ronald Reagan’s anti-environmental actions in the early 1980s. Today, in lieu of modern assaults against environmental protections, Mike’s oral history sheds light on ways environmentalists managed those challenges and even expanded their purview to international issues.

Amanda Tewes pick:

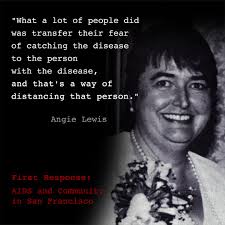

Paul Burnett’s pick:

I choose nurse educator and clinical nurse Angie Lewis, who worked at UC San Francisco during the early years of the AIDS crisis. In Lewis’ interview, we really hear what it was like to first learn of this then-unknown disease that was killing gay people in San Francisco in the early 1980s. But we also hear touching stories of the mobilization of community and medical support for those who were suffering from AIDS.

David Dunham’s pick:

David Blackwell: African American Faculty and Senior Staff Oral History Project. Named after an esteemed mathematician and the first African-American tenured professor at Cal, David Blackwell Hall opened this fall to honor Professor Blackwell. Read more about his pioneering life in his oral history, part of our African American and Senior Faculty Oral History Project.

Todd Holmes’ pick:

I’d recommend Francis Mary Albrier: Determined Advocate for Racial Equality. This oral history captures the extraordinary life of one of Berkeley’s most prominent citizens, from her leading role in fighting discriminatory hiring in the City’s schools and businesses to desegregating the famed Richmond Shipyards. Moreover, through her oral history, you get a clear view of the many unsung citizens that organized communities of color to collectively push for change.

Shanna Farrell’s pick:

When I was first learning how to conduct longform interviews, I drew inspiration from Willa Baum, former director of the Oral History Center. She was an amazing interviewer, and her oral history interview provided insight into who she was, what drove her, and how she built the reputation of our office.

NHPRC Supports Processing Environmental Collections at The Bancroft Library

The Bancroft Library is currently engaged in a two-year project funded by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission to process a range of archival collections relating to environmental movements in the West. A leading repository in documenting U.S. environmental movements, The Bancroft Library is home to the records of many significant environmental organizations and the papers of a range of environmental activists.

Among the library’s environmental holdings are the records of the Sierra Club, including correspondence of naturalist and Club founder John Muir, the records of the Save-the-Redwoods League, and the records of Save the Bay. Among the collections already made available to researchers in this current NHPRC-funded project are the records of the Coalition for Alternatives to Pesticides, the records of the Small Wilderness Area Preservation group, the papers of environmental lawyer Thomas J. Graff, and the records of California-based Trustees for Conservation. Collections scheduled to be processed in the next eighteen months include the records of such major environmental organizations as Friends of the River, Friends of the Earth, the Rainforest Action Network, and the Earth Island Institute.

What’s In a Name? How One Bancroft Library Archivist Shed Light on a Gold Rush Era Gem

Background: Each year the Bancroft Library acquires a sizeable amount of new manuscript material. The sheer quantity of this material necessitates that the archivists who handle, process, and catalog these materials, exercise considerable judgment in balancing thorough and accurate descriptions that facilitate access with the need to make the materials available as quickly as possible. Archivists are trained to determine just the right level of description to allow for sufficient discovery. In the case of very large collections, an archivist rarely describes materials at the item-level.

But sometimes a single item merits closer examination and considerable research to render it truly accessible to the library’s researchers. One such item recently caught my attention–

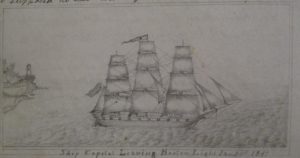

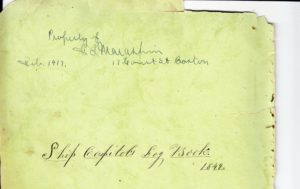

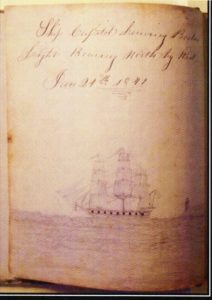

The “Ship Capitol’s Log Book” is the account of a passenger aboard one of the first ships to head to California during the gold rush, arriving in San Francisco in July 1849.

At first glance, it looked like a typical gold rush era journal, with daily entries describing conditions and life aboard the ship as it made its way from Boston to San Francisco around Cape Horn. But this one stood out because it included several finely rendered pencil drawings throughout including ships, shorelines, and even an albatross at rest.

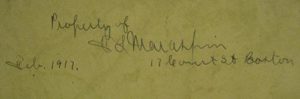

Unlike similar journals that have crossed my desk, this one came with a contemporary inscription inside the front cover identifying the ship and giving the date (and, incidentally, providing a neat title for the catalog record). The accompanying description provided by the vendor was also intriguing, noting that there was an additional inscription in a different hand: “Above this [title] is the inscription of Paul Maraspin, another passenger on the ship and the ancestor of the log’s most recent owner…. It is not clear who authored the journal.” However, upon closer examination, I determined that this might not be the case. It was clearly two initials followed by “Maraspin” but it didn’t look like either a “P” or “Paul.” I could not clearly make out the first initial, but the second one looked like an “L,” and below that a street address of “17 Court Street, Boston” and the date “Feb. 1917.”

The vendor also noted that the lettering of the captions of the drawings was in a third hand, suggesting that someone other than the author of the journal might be the source of those. Also noted was the composer of several songs recorded in the journal, B.F. Whittemore.

The clues from the vendor and my own initial assessment of the journal suggested that a bit more research might make the journal infinitely more discoverable and useful. I became intrigued by the name of the owner of the journal, and the information suggested by the vendor just didn’t seem to fit with the facts the artifact was presenting to me.

Archivists have at their disposal the same research tools many other people do…the internet and access to genealogical sites that hold various records. There is a tremendous amount of information out there that makes this kind of research much more efficient than it used to be. Of course, too much information can also be problematic and it is the skillful researcher who can quickly sort through large amounts information and surmise whether more research will yield tangible results or, lacking that, have to call the effort “good enough.”

In this particular case, I discovered information about the owner’s signature that led to the solution of numerous puzzles presented by the journal itself, including how he came into possession of it, its likely author, the identity of the illustrator, the history of the lyricist of several songs, the author of the final song in the journal, and the history of the ship and its captain, Thorndike Procter.

Because Maraspin struck me as an unusual name, my first step was a Google search on the name. This resulted in the discovery of a Maraspin Creek in Barnstable, Massachusetts. Assuming the creek was named after a prominent family in the area, the information gave me hope that I could find out more about them and explore those connections.

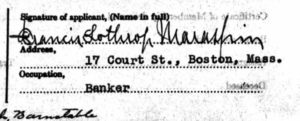

I switched over to Ancestry.com to do a direct search on Paul Maraspin from Barnstable, Massachusetts around the time period of 1849. Numerous records surfaced that indicated a Paul Maraspin from Barnstable had been married and had several daughters, but none of whose initials matched the inscription in the journal. But then I found an application to the Sons of the American Revolution from 1937 for Paul Maraspin that listed his wife, Mary Eliza Davis, and one child, a son, Francis Lothrop Maraspin. Paul Maraspin had this son rather late in life, at the age of 52, and some 16 years after he had sailed to California. Looking back at the inscription, I could see now that the autograph was, in fact, “F.L. Maraspin.”

I then turned to confirming that this was, indeed, the Francis Lothrop Maraspin in the application form. Back to Google, I found an article from the Cape Cod Times lauding a Francis Maraspin’s 100th birthday in 1966. Back to Ancestry.com I found another Sons of the American Revolution application from 1935, this time for a Francis Lothrop Maraspin. I could see print coming through from the backside of the page and paged forward to see it. Right at the top was the statement identifying Paul Maraspin as his father. But the real clincher was at the bottom.The application was signed by Francis Lothrop Maraspin himself with his typed address, 17 Court Street, Boston.

And from the journal again:

As you can see, the signature and address matched the inscription on the journal cover perfectly and we now knew we had our owner and could assume, with reasonable certainty, that the likely author of the journal was Francis Lothrop’s father, Paul Maraspin.

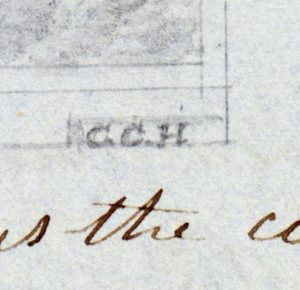

I shared these initial findings with my supervisor, Randal Brandt, who directed me to a publication that would be key to figuring out the rest of the puzzles. The Argonauts of California, published by C.W. Haskins in 1890, is an invaluable source of information about the gold seekers who came to California. The passenger lists it contains were crucial in figuring out the names of people associated with the journal. We now knew who had written the journal but who had done the drawings? And what about the composer of those numerous songs recorded in the journal? A closer examination of the drawings proved fruitful. Of the nine drawings, two of them had the initials “CCH” in the lower right hand corner.

A quick perusal of the Capitol’s passenger list turned up only one possible match, a C.C. Hosmer. Now we knew the name of the illustrator. Back to Ancestry.com again, I went hunting for more information about him and found out his full name, Chester Cooley Hosmer (1823-1879). Because Chester Cooley Hosmer is also an unusual name, on a whim I Googled it along with the word “Capitol.” The very first result was a library catalog listing in the Special Collections of the Jones Library in Amherst, Massachusetts for Chester Cooley Hosmer’s journal documenting the same trip aboard the Capitol. Describing it as a journal “illustrated throughout with his drawings,” the catalog listing included scans of two pages with drawings. Here is one of them.

One can readily see the style of these drawings match those in the Maraspin journal. Not only did we now know our illustrator but also the location of his journal from the very same voyage.

Turning to the name listed as the songwriter, B.F. Whittemore (sometimes spelled incorrectly as “Whitmore” in passenger lists), a search turned up another interesting character. The Wikipedia entry for Benjamin Franklin Whittemore states that he went on to become a minister in the Union Army and then elected to the state legislature of South Carolina and eventually the House of Representatives.

Others identified in this process included the composer of the final song lyrics in the journal titled, “A Song Dedicated to the Officers of the Ship Capitol,” and signed “W.T. old friend.” Again, the passenger lists were the key as only one person had those initials, W.T. Hubbard.

More research on the ship and lists revealed the full name of the captain, Thorndike Procter of Salem, Massachusetts.

As might be true with any group of persons traveling so far from home for so long, there is inevitable tragedy as well as triumph. Captain Thorndike Procter committed suicide in San Francisco Bay on October 17, 1849. It was reported in the papers that the captain “had been lately subject to occasional fits of derangement, during the last of which he jumped overboard, and was drowned….” Nine weeks later, Paul Maraspin’s young “old friend,” William.T. Hubbard, just 23 years of age, also died by drowning in San Francisco Bay on Christmas Eve.

The work of improving access and discoverability to our collections is at the heart of what we do as library professionals. Unknown people become known, their stories and lives become real to us, and as you read this journal now you can see the intertwining of their lives. One hundred and sixty-eight years later, two journals from the same trip are virtually reunited because of the work of archivists and catalogers separated by time and a continent. In this way, library professionals contribute to a very large cultural jigsaw puzzle that, slowly but surely, becomes ever more complete.

To see the completed catalog record for this item please use this link:

http://oskicat.berkeley.edu/record=b23750637~S1