Tag: research

Wrapping up our NEH-funded project to help text and data mining researchers navigate cross-border legal and ethical issues

In August 2022, the UC Berkeley Library and Internet Archive were awarded a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) to study legal and ethical issues in cross-border text and data mining (TDM).

The project, entitled Legal Literacies for Text Data Mining – Cross-Border (“LLTDM-X”), supported research and analysis to address law and policy issues faced by U.S. digital humanities practitioners whose text data mining research and practice intersects with foreign-held or -licensed content, or involves international research collaborations.

LLTDM-X is now complete, resulting in the publication of an instructive case study for researchers and white paper. Both resources are explained in greater detail below.

Project Origins

LLTDM-X built upon the previous NEH-sponsored institute, Building Legal Literacies for Text Data Mining. That institute provided training, guidance, and strategies to digital humanities TDM researchers on navigating legal literacies for text data mining (including copyright, contracts, privacy, and ethics) within a U.S. context.

A common challenge highlighted during the institute was the fact that TDM practitioners encounter expanding and increasingly complex cross-border legal problems. These include situations in which: (i) the materials they want to mine are housed in a foreign jurisdiction, or are otherwise subject to foreign database licensing or laws; (ii) the human subjects they are studying or who created the underlying content reside in another country; or, (iii) the colleagues with whom they are collaborating reside abroad, yielding uncertainty about which country’s laws, agreements, and policies apply.

Project design

We designed LLTDM-X to identify and better understand the cross-border issues that digital humanities TDM practitioners face, with the aim of using these issues to inform prospective research and education. Secondarily, we hoped that LLTDM-X would also suggest preliminary guidance to include in future educational materials. In early 2023, we hosted a series of three online round tables with U.S.-based cross-border TDM practitioners and law and ethics experts from six countries.

The round table conversations were structured to illustrate the empirical issues that researchers face, and also for the practitioners to benefit from preliminary advice on legal and ethical challenges. Upon the completion of the round tables, the LLTDM-X project team created a hypothetical case study that (i) reflects the observed cross-border LLTDM issues and (ii) contains preliminary analysis to facilitate the development of future instructional materials.

We also charged the experts with providing responsive and tailored written feedback to the practitioners about how they might address specific cross-border issues relevant to each of their projects.

Guidance & Analysis

Case Study

Extrapolating from the issues analyzed in the round tables, the practitioners’ statements, and the experts’ written analyses, the Project Team developed a hypothetical case study reflective of “typical” cross-border LLTDM issues that U.S.-based practitioners encounter. The case study provides basic guidance to support U.S. researchers in navigating cross-border TDM issues, while also highlighting questions that would benefit from further research.

The case study examines cross-border copyright, contracts, and privacy & ethics variables across two distinct paradigms: first, a situation where U.S.-based researchers perform all TDM acts in the U.S., and second, a situation where U.S.-based researchers engage with collaborators abroad, or otherwise perform TDM acts in both U.S. and abroad.

White Paper

The LLTDM-X white paper provides a comprehensive description of the project, including origins and goals, contributors, activities, and outcomes. Of particular note are several project takeaways and recommendations, which we hope will help inform future research and action to support cross-border text data mining. Our project takeaways touched on seven key themes:

- Uncertainty about cross-border LLTDM issues indeed hinders U.S. TDM researchers, confirming the need for education about cross-border legal issues;

- The expansion of education regarding U.S. LLTDM literacies remains essential, and should continue in parallel to cross-border education;

- Disparities in national copyright, contracts, and privacy laws may incentivize TDM researcher “forum shopping” and exacerbate research bias;

- License agreements (and the concept of “contractual override”) often dominate the overall analysis of cross-border TDM permissibility;

- Emerging lawsuits about generative artificial intelligence may impact future understanding of fair use and other research exceptions;

- Research is needed into issues of foreign jurisdiction, likelihood of lawsuits in foreign countries, and likelihood of enforcement of foreign judgments in the U.S. However, the overall “risk” of proceeding with cross-border TDM research may remain difficult to quantify; and

- Institutional review boards (IRBs) have an opportunity to explore a new role or build partnerships to support researchers engaged in cross-border TDM.

Gratitude & Next Steps

Thank you to the practitioners, experts, project team, and generous funding of the National Endowment for the Humanities for making this project a success.

We aim to broadly share our project outputs to continue helping U.S.-based TDM researchers navigate cross-border LLTDM hurdles. We will continue to speak publicly to educate researchers and the TDM community regarding project takeaways, and to advocate for legal and ethical experts to undertake the essential research questions and begin developing much-needed educational materials. And, we will continue to encourage the integration of LLTDM literacies into digital humanities curricula, to facilitate both domestic and cross-border TDM research.

[Note: this content is cross-posted on the LLTDM blog.]

Upcoming Workshop: Can I Mine That? Should I Mine That? A Clinic for Copyright, Ethics & More in TDM Research

Workshop Date/Time: Wednesday, March 8, 2023, 11:00am–12:30pm

Register to receive Zoom link

If you are working on a computational text analysis project and have wondered how to legally acquire, use, and publish text and data, this workshop is for you! We will teach you 5 legal literacies (copyright, contracts, privacy, ethics, and special use cases) that will empower you to make well-informed decisions about compiling, using, and sharing your corpus. By the end of this workshop, and with a useful checklist in hand, you will be able to confidently design lawful text analysis projects or be well positioned to help others design such projects. Consider taking alongside Copyright and Fair Use for Digital Projects.

Please sign up today and join us online on March 8.

Undergraduate Library fellows offering research assistance

Students: Need help with your research?

Starting this month, undergraduate Library fellows are offering in-person peer library research assistance. Fellows are available 1-3 p.m. Mondays and Wednesdays through Nov. 30.

A Library Research Journey (Pandemic Edition)

Even beyond those who believe that librarians sit around and read books all day (which would be delightful but is most definitely not our reality), many are surprised to learn that librarians double as active researchers. This is especially true in settings where librarians are members of the faculty, but even where that isn’t the case, such as at Berkeley, librarians are born investigators and it carries over into wanting to find out about and add to knowledge of our settings.

What does it look like to conduct library research? Glad you asked! In our case, it started with a conversation and an idea. Natalia Estrada (now Berkeley’s Political Science and Public Policy Librarian, then the Social Sciences Collection and Reference Assistant and in library school) and I were talking about how much we admired the work of Kaetrena Davis Kendrick. Kendrick wrote a foundational work in the study of librarian workplace morale, The Low Morale Experience of Academic Librarians: A Phenomenological Study, and it sparked many more studies on this topic. But, where were the studies of library staff experiences? We wanted to find out!

We were lucky to recruit two colleagues who added so much to the team: Bonita Dyess, Circulation/Reserves Supervisor at the Earth Sciences/Map Library, and Celia Emmelhainz, Berkeley’s Anthropology & Qualitative Research Librarian. First we applied for (and eventually got) funding for the research from LAUC (the Librarians Association of the University of California). This meant we could pay for transcribing our interviews, give the participants gift cards, and buy qualitative data analysis software. Then we applied for (and got) approval from the IRB (Institutional Review Board), making sure we were complying with processes for research with human subjects.

Here’s where the “pandemic edition” part comes in. All this planning and applying, starting in November 2019, took time; so, at the point we were actually ready to recruit participants, it was April 2020. We were sheltering in place, and not sure how this all would work (although it was probably better than having to go virtual in mid-stream)! Nevertheless, we hurled out information about and invitations to be part of the study to every list-serv, association, and friendly librarian we could think of, nationwide. We ended up doing 34 interviews with academic library staff from a range of locations and institution types (purposefully excluding the UC system), during a three-week period in May-June 2020. Due to COVID these were all online, either by phone or Google Meet (sort of like Zoom), and we asked a structured list of questions, with room for branching into other topics, or diving deeply. Celia trained a wonderful student to transcribe the interviews, and once we had those transcripts and stripped identifying information from them, we were off– coding away (using MAXQDA software), and drawing themes, quotes, recommendations, and other findings from the surprisingly rich information we’d collected.

Next—we had to start getting the information out into the world! Our eventual goal is to write a paper, or several, for publication. There are a number of library and information science journals out there that we are considering… but that takes time as well, and we wanted to start presenting our findings sooner. So, we did an “initial findings” presentation to the UC Berkeley Library Research Working Group, and then stepped into the big time with acceptance to present a poster at the 2021 Association of College and Research Libraries online conference (our poster got almost 600 views), and with a webinar we did for the Pennsylvania Library Association (both the poster and the webinar slides are available through the UC’s eScholarship portal). All our work to get to this point is hopefully now helping others.

And, a word about connecting with our participants. We were bowled over by their generosity with us and by all they had to say: much that we didn’t expect, and much that they were grateful someone was even asking about. It ended up that we had captured one of the last opportunities to get a snapshot of pre-COVID library staff life; people were still in limbo, and talked about their regular jobs before any lockdowns, for the most part. At that point most expected to be back in their libraries and all to be normal by the end of the summer 2020. We know now that that didn’t happen, and we know that library re-openings and staff roles in them have been challenging and sometimes contentious; we wish we’d known to ask for permission to re-interview our participants—even if only to check in with them. But how could we have known? We wonder how they are.

So now, we have papers to write, and thinking to do about how to take our questions into new avenues of research—because it’s a never-ending, and completely exciting process, and, we suspect, will be very different (easier? or not?) in the post-COVID landscape. Do you have ideas for us? We’d love to hear them! Or want to hear more about our morale study? Please get in touch with us at librarystaffmorale@berkeley.edu!

Law & ethics in research and archiving social media of Myanmar resistance

On March 9, 2021, the Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Institute of East Asian Studies, the Institute of South Asia Studies, and the Human Rights Center at UC Berkeley hosted the online symposium Scholar-Activism and the Myanmar Resistance. The event invited scholar-activists to analyze and strategize for resistance to Myanmar’s military coup. The Office of Scholarly Communication Services collaborated with Dr. Hilary Faxon, Ciriacy-Wantrup Postdoctoral Fellow at UC Berkeley, to organize an afternoon workshop to explore the law, ethics, methods, and goals of archiving social media coverage of the coup.

Faxon highlighted that in the months since the military seized power on February 1, the internet has become a key domain of struggle in Myanmar. The military has cut off internet access and (before being banned) used Facebook to disseminate misinformation. Meanwhile, democracy activists have used social media alongside traditional tactics of street protests and general strikes to resist the regime.

The workshop brought together a diverse group of participants from across and beyond campus with perspectives from human rights, research and journalism, including WITNESS and Berkeley’s Human Rights Investigation Lab. Stacy Reardon, Literatures and Digital Humanities Librarian, discussed services and workshops offered by Digital Humanities at Berkeley, as well as tools used to conduct DH research, such as the Wayback Machine, Conifer, 4k download, Adobe Bridge, and others.

The Office of Scholarly Communication Services provided an overview for how to navigate law and policy issues when researchers are scraping, archiving, or text mining third party content, like social media posts, website text or images, or articles from databases. We addressed common issues that arise in research and archiving, including copyright, license agreements and website terms of use, privacy questions, and ethical considerations.

Workshop discussions were centered around a commitment to a shared ethics of care approach to using, sharing, and archiving information social media content related to the coup. The ethics of care framework suggests that what we do as information collectors or analyzers will affect other people, particularly when people have less structural power, and according to the ethics of care, we should care about that. This becomes immediately apparent when deciding whether or how to collect, process, and share potentially sensitive social media posts, images, and videos from the Myanmar coup, especially when doing so could have dire consequences for activists who are the subjects of those posts.

During the workshop, we talked about how the Library has adopted a form of ethics of care in our approach to making decisions about what collection materials we’ll digitize and put online. Our version of ethics of care is framed as a balancing principle: that is, we look to whether the value to researchers, the public, or cultural communities in digitizing and sharing the content outweighs the potential for harm or exploitation of people, resources, or knowledge.

Several takeaways emerged by the end of the workshop discussion:

- Protecting and defending human rights: Archiving material from social media—including videos, photos, and live streams—might help ensure perpetrators of violence are held accountable, but the production and circulation of such materials can also be highly-incriminating for media creators and platform users.

- Collecting is collaborative: Usage of archives is bound up with the intentions of those creating material, and so archiving requires an ongoing, bi-directional conversation between those creating content and those doing the archiving.

- Circumstances change: Both ethical and organizational approaches should be discussed and decided in advance of archiving. But expect situations to change – what is safe and straightforward to keep today may be more risky tomorrow.

- Capturing versus sharing: These are different processes, and “archiving” does not necessarily have to entail both. The benefits and risks associated with collecting data are distinct from those associated with sharing data or making it publicly available, so these processes should be considered separately.

- Law and ethics: Regardless of what is allowed under U.S. copyright law, there may be other contracts and terms of service that restrict what you can do with materials. Moreover, collecting voluntarily-released data may not violate legal privacy rights, but may present ethical questions.

- Data security: Develop a Data Management Plan that addresses organization and protection both during archiving, and after the project is completed. Consider a special purpose account for collaborations and data sharing.

- Data hygiene: Don’t collect more than you need.

- Practical strategies: Tools may depend on the specific goals of a researcher and the scale of the project. It is important to ask what, precisely, you mean when you say “archiving,” and what the purpose of creating your archive might be.

- Seek out a community of practice to support and situate your efforts.

We hope the workshop helped researchers to better understand the legal and ethical considerations in collecting, processing, and sharing potentially sensitive social media content of events like the Myanmar resistance. The Library and a broad community of supporters are here to help scholars address these challenges and equip them to proceed with confidence, care, and sound practices.

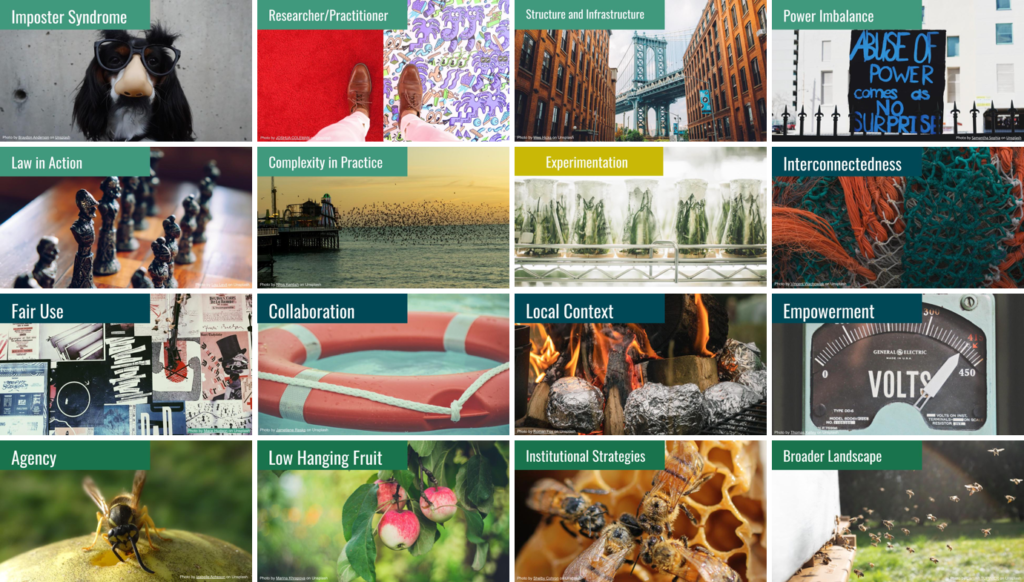

What happened at the Building LLTDM Institute

This update is cross-posted from the Building LLTDM blog.

On June 23-26, we welcomed 32 digital humanities (DH) researchers and professionals to the Building Legal Literacies for Text Data Mining (Building LLTDM) Institute. Our goal was to empower DH researchers, librarians, and professional staff to confidently navigate law, policy, ethics, and risk within digital humanities text data mining (TDM) projects—so they can more easily engage in this type of research and contribute to the further advancement of knowledge. We were joined by a stellar group of faculty to teach and mentor participants. Building LLTDM is supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Why was the Institute needed?

Until now, humanities researchers conducting text data mining in the U.S. have had to maneuver through a thicket of legal issues without much guidance or assistance. As an example, take a researcher scraping content about Egyptian artifacts from online sites or databases, or downloading videos about Egyptian tomb excavations, in order to conduct automated analysis about religion or philosophy. The researcher then shares these content-rich data sets with others to encourage research reproducibility or enable other researchers to query the data sets with new questions. This kind of work can raise issues of copyright, contract, and privacy law. It can also raise concerns around ethics, for example, if there are plausible risks of exploitation of people, natural or cultural resources, or indigenous knowledge.

Potential law and policy hurdles do not just deter text data mining research: They also bias it toward particular topics and sources of data. In response to confusion over copyright, website terms of use, and other perceived legal roadblocks, some digital humanities researchers have gravitated to low-friction research questions and texts to avoid making decisions about rights-protected data. When researchers limit their research to such sources, it is inevitably skewed, leaving important questions unanswered, and rendering resulting findings less broadly applicable.

Moving an interactive, design-thinking Institute online

After months of preparation, we had been looking forward to working and learning together at UC Berkeley, but the world had other plans for our Institute. Due to the global health crisis, we had to transform our planned in-person, intensive workshop into an interactive and relevant remote experience.

How did we do this? The pandemic meant we had to transition everything online, which of course presents challenges for a design-thinking framework. We are thrilled that our approach to interactive remote pedagogy was successful! (You can check out the schedule and framework in our Participant Packet.) The substantive content was pre-recorded and delivered in a flipped classroom model. Faculty created a series of short videos, and shared readings relevant to the legal literacies. We also provided the video transcripts and slides to participants to promote accessibility and accommodate multiple learning styles.

We used Zoom to meet synchronously for discussion in groups of various sizes. We used Slack for asynchronous communication, and interactive tools such as Mural for design thinking exercises like journey mapping so that everyone could live edit and collaborate. We capped each day with a “happy half hour” on Zoom as an informal way to get to know each other a little better, even from afar.

We also relied on an institute moderator and daily writing exercises to reinforce the design-thinking stages and learning outcomes. Each night, we reviewed the participants’ free-writes and began the next morning by reflecting back to the participants the themes from what they had shared.

Reflections on goals: social justice & effective empowerment

One of our priorities for the Institute was to invite a diverse pool of participants, including those involved in social justice research, in order to maximize the public value impact of Building LLTDM. We looked for demonstrated commitments to diversity and equity but could hardly have imagined the breadth and depth of experiences that applicants were willing to share. The selected participants research everything from understanding “place” data from community histories of historic African American settlements to the development of AIDS activist networks in communities of color; to portrayals of autism in literature; and more. Others demonstrated a commitment to bringing back the skills they learn to expand TDM opportunities for students and communities who have traditionally been marginalized or under-resourced. They also came from a variety of institution types, from research advising and support experience, professional roles, levels of experience with TDM, career stages, and disciplinary perspectives.

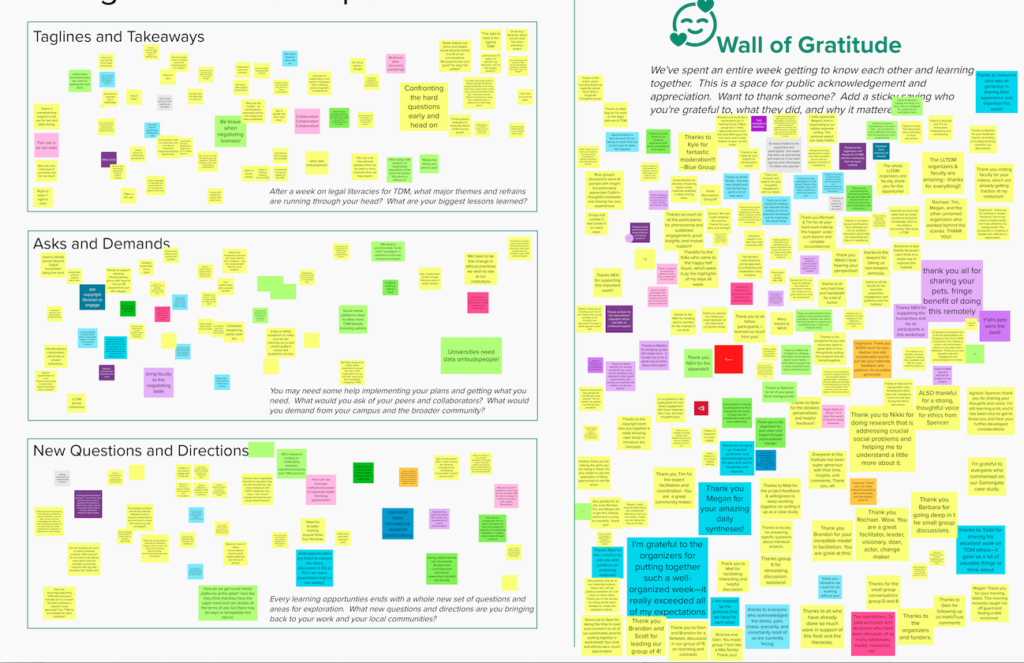

We are also moved by the participants’ own reflections on the experience. One of the last interactive exercises we hosted during the online Institute was a collective week-in-review discussion, and gratitude wall. We asked the participants to share what they were thankful for, highlighting other participants where possible. So many of the participants wrote about how valuable the learning experience was and how thoughtfully it was put together and delivered.

We can’t express the transformational impact of the week better than the participants, themselves. In Institute evaluation forms, they shared feelings like:

- “This is by far the best organized event that I have ever attended. The content was by far the most substantive. The faculty were by far the most engaged. A+ across the board.”

- “I am so grateful to have had the opportunity to engage with a diverse group of scholars (researchers and professionals)… The deliberately thought through breakdown and mix fostered incredibly valuable discussions and I would hope this kind of framework is used as a best practice for future DH institutes of all kinds going forward. Also, thank you for such an amazing virtual experience which I can only imagine took a tremendous amount of work to coordinate and plan with limited time to shift to an entirely different format–I was overjoyed to critically engage with complex subjects…”

- “This has been phenomenal. I don’t want to qualify it (by adding something like “…for having to be moved online”), because it’s been so, so good: well organized, thoughtful, and human throughout.”

- “There was clearly so much thought, care, and planning that went into the preparation of this institute, and it was an amazing opportunity to learn from a group of people — organizers, faculty, and participants — who all have such deep expertise. The video and readings lists alone are a huge resource, but to be able to process and reflect on that material together with a diverse group of people was really wonderful.”

Next steps, and our own gratitude

What’s next for Building LLTDM? The “Institute” is not over yet; only the 1-week training is complete. The cohort will be meeting again virtually in February 2021 to discuss how implementation of the literacies into our local communities and practices has gone. In the meantime, as the participants bring back the law and policy literacies they’ve learned to their home institutions, we are excited to see several cohort members already organizing their own post-Institute research subgroups, such as those whose TDM work relies heavily on social media content, and others who are exploring how to disseminate the Building LLTDM literacies within other instructional formats and frameworks.

As part of the grant, the project team will also be aggregating the resources from the Institute and developing supplementary material for an Open Educational Resource (OER). We know there is a large community of TDM researchers and professionals who may be interested in or who can benefit from these materials, and the OER will be made available for broad reuse in the public domain.

Thank you to all the participants for their insights and contributions, willingness to share, and flexibility in transitioning to a fully-remote Institute. Thank you to all the faculty for their unmatched legal and policy expertise, ongoing commitment to mentorship, and adaptability in content creation and delivery. And thank you again to the NEH for making such a meaningful experience possible.

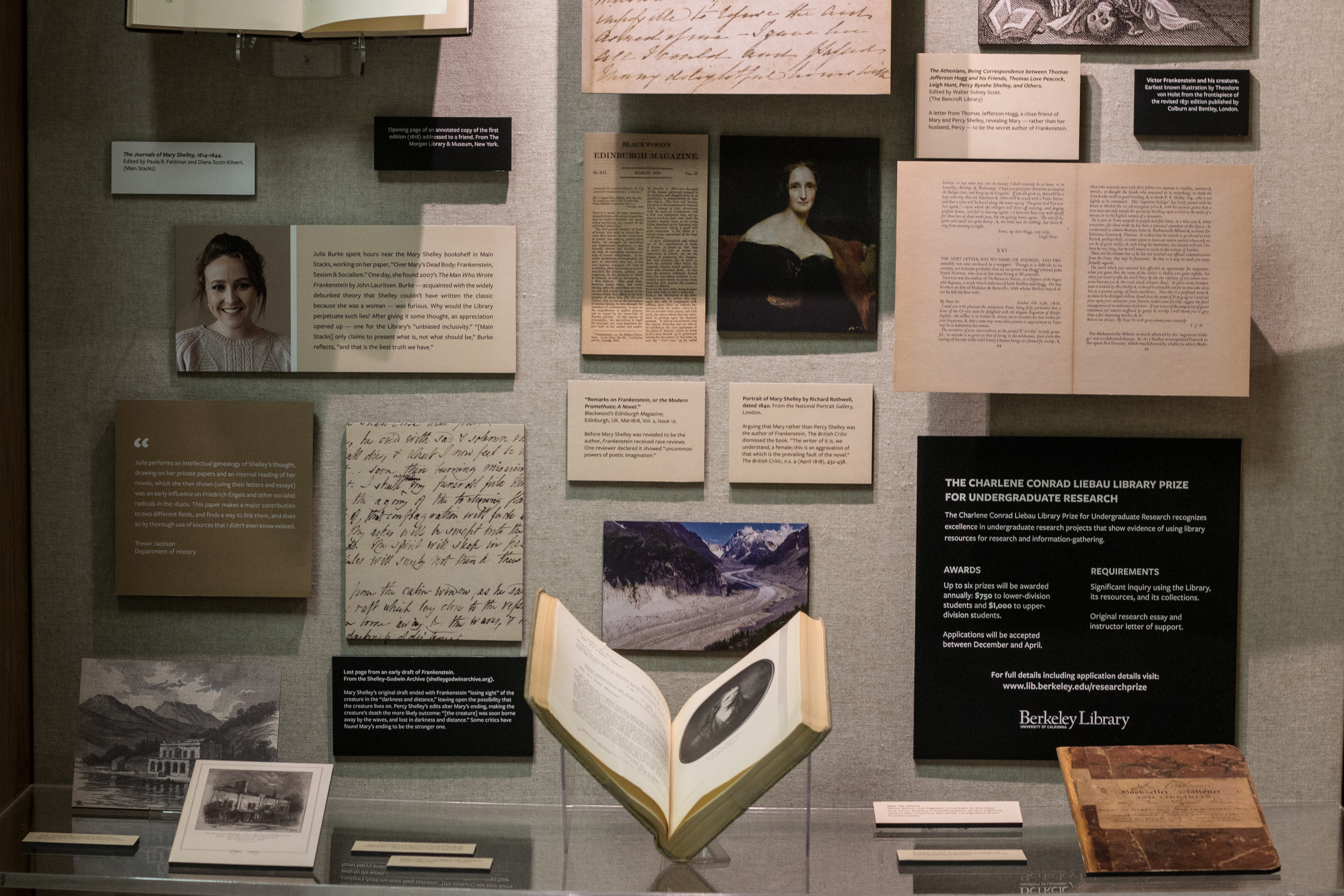

Library Prize Exhibit 2018 about Frankenstein Now on View

“A king is always a king –and a woman is always a woman: his authority and her sex ever stand between them and rational converse.” – Mary Wollstonecraft

Recent Berkeley graduate Julia Burke begins her essay, “Over Mary’s Dead Body: Frankenstein, Sexism & Socialism,” a historiography and cultural critique of Shelley’s Frankenstein, with the above epigraph from Mary Wollstonecraft, the great political philosopher and Mary Shelley’s mother. Burke’s research into the reception of Frankenstein and in its possible influence on socialist radicals of the 1840s earned her the prestigious 2018 Charlene Conrad Liebau Library Prize for Undergraduate Research, an annual prize awarded to students who have done exceptional research and made significant use of the Library’s resources.

Burke’s paper is the subject of this semester’s rotating Library Prize Exhibit, located on the second floor of Doe between the Heyns Reading Room and Reference Hall. Drawing on the Library and the Bancroft’s broad collections, the exhibit outlines Burke’s arguments in visual form with digitized replicas of the original 1818 edition of Frankenstein, an early copy of The Communist Manifesto, letters, contemporary reviews, and more. The exhibition of Burke’s project coincides with the bicentennial of Frankenstein’s publication. Originally published anonymously, Frankenstein’s true author was greatly contested, as Burke explores. Today it is one of the most important works of the literary canon and the most read novel in undergraduate courses nationwide. The exhibit was curated by Stacy Reardon, the Literature and Digital Humanities Librarian, and designed by Aisha Hamilton, the Exhibits and Environmental Graphics Coordinator. The exhibit will be up until April 2019.

edited by Paula R. Feldman and Diana Scott-Kilvert

Photo by J. Pierre Carrillo for the UC Berkeley Library

Mary Shelley

First Edition

Photo by J. Pierre Carrillo for the UC Berkeley Library

collected and edited by Frederick L. Jones

Photo by J. Pierre Carrillo for the UC Berkeley Library

The Charlene Conrad Liebau Library Prize for Undergraduate Research is awarded annually, and submissions are now open to all undergraduates until April 18, 2019. Any project from a credit course at U.C. Berkeley from Spring 2018 to Spring 2019 (lower division) or Summer 2018 to Spring 2019 (upper division) is eligible. The project can be in progress as of the due date of the application. In addition to a monetary award of $750 for lower-division winners and $1000 for upper-division winners, the recipients of the Library Prize publish their work in eScholarship, and two will be featured in an exhibit in the Library. Find out more information here.

You can see the rest of this year’s winners and honorable mentions here. Don’t forget to stop by the exhibit to see Burke’s work in person. More books related to Frankenstein in honor of the bicentennial can be found here.

From the Archives: Staff Picks

This month, we’re bringing you a special edition of our From the Archives department. Below are interviews, all available in the OHC archives, recommended by each of us. Enjoy digging through the crates!

Martin Meeker’s pick:

Andre Tchelistcheff: Grapes, Wine, and Technology. Some lives in our collection of interviews are just profoundly interesting, and well worth digging into. This might be because of difficulties surmounted, achievements recognized, or simply the quality of the telling. Our 1979 oral history with Andre Tchelistcheff reveals one such life that ticks all of those boxes. From his birth in Russia in 1901, through his harrowing escape during the Revolution, to his years in France studying viticulture, and his decades quite literally remaking California’s wine industry, Tchelistcheff lived a remarkably influential life while remaining rooted in his passions throughout.

Roger Eardley-Pryor’s pick:

J. Michael McCloskey (Mike McCloskey), “Sierra Club Executive Director and Chairman, 1980s-1990s: A Perspective on Transitions in the Club and the Environmental Movement,” conducted in 1998 and published in 1999, is the second oral history with Mike McCloskey as part of the Sierra Club Oral History Project. Mike, a longtime leader in one of the largest environmental organizations in the United States, discusses the Club’s growing pains associated with an upsurge in membership amid Ronald Reagan’s anti-environmental actions in the early 1980s. Today, in lieu of modern assaults against environmental protections, Mike’s oral history sheds light on ways environmentalists managed those challenges and even expanded their purview to international issues.

Amanda Tewes pick:

Paul Burnett’s pick:

I choose nurse educator and clinical nurse Angie Lewis, who worked at UC San Francisco during the early years of the AIDS crisis. In Lewis’ interview, we really hear what it was like to first learn of this then-unknown disease that was killing gay people in San Francisco in the early 1980s. But we also hear touching stories of the mobilization of community and medical support for those who were suffering from AIDS.

David Dunham’s pick:

David Blackwell: African American Faculty and Senior Staff Oral History Project. Named after an esteemed mathematician and the first African-American tenured professor at Cal, David Blackwell Hall opened this fall to honor Professor Blackwell. Read more about his pioneering life in his oral history, part of our African American and Senior Faculty Oral History Project.

Todd Holmes’ pick:

I’d recommend Francis Mary Albrier: Determined Advocate for Racial Equality. This oral history captures the extraordinary life of one of Berkeley’s most prominent citizens, from her leading role in fighting discriminatory hiring in the City’s schools and businesses to desegregating the famed Richmond Shipyards. Moreover, through her oral history, you get a clear view of the many unsung citizens that organized communities of color to collectively push for change.

Shanna Farrell’s pick:

When I was first learning how to conduct longform interviews, I drew inspiration from Willa Baum, former director of the Oral History Center. She was an amazing interviewer, and her oral history interview provided insight into who she was, what drove her, and how she built the reputation of our office.

Research Software Survey Results Published

“Research software” presents a significant challenge for efforts aimed at ensuring reproducibility of scholarship. In a collaboration between the UC Berkeley Library and the California Digital Library, John Borghi and I (Yasmin AlNoamany) conducted a survey study examining practices and perceptions related to research software. Based on 215 participants, representing a variety of research disciplines, we presented the findings of asking researchers questions related to using, sharing, and valuing software. We addressed three main research questions: What are researchers doing with code? How do researchers share their code? What do researchers value about their code? The survey instrument consisted of 56 questions.

We are pleased to announce the publication of paper describing the results of our survey “Towards computational reproducibility: researcher perspectives on the use and sharing of software” in PeerJ Computer Science. Here are some interesting findings from our research:

- Results showed that software-related practices are often misaligned with those broadly related to reproducibility. In particular, while scholars often save their software for long periods of time, many do not actively preserve or maintain it. This perspective is perhaps best encapsulated by one of our participants who, when completing our open response question about the definition of sharing and preserving software, wrote ” ‘Sharing’ means making it publicly available on Github. ‘Preserving’ means leaving it on GitHub”.

- Only 50.51% of our participants were aware of software-related community standards in their field or discipline.

- Participants from computer scientists reported that they provide information about dependencies and comments in their source code more than those from other disciplines.

- Regarding to sharing software, we found that the majority of participants who do not share their code, they indicated that had privacy issues and time limitation to prepare code for sharing.

- Regarding to preservation, only a 20% of our participants reported that they save their software for eight years or more, 40% indicated that they do not prepare their software for long term preservation. The majority of participants (76.2%) indicated that they use Github for preserving software.

- The majority of our participants indicated that view code or software as “first class” research products that should be assessed, valued, and shared in the same way as a journal article. However, our results also indicate that there remains a significant gap between this perception and actual practice. As a result we encourage the community to work together for creating programs to train researchers early on how to maintain their code in the active phase of their research.

- Some of researchers’ perspectives on the usage of code/software:

“Software is the main driver of my research and development program. I use it for everything from exploratory data analysis, to writing papers…- “I use code to document in a reproducible manner all steps of data analysis, from collecting data from where they are stored to preparing the final reports (i.e. a set of scripts can fully reproduce a report or manuscript given the raw data, with little human intervention).”

- Some of researchers’ perspectives on sharing and preservation:

- “I think of sharing code as making it publicly accessible, but not necessarily advertising it. I think of preserving code as depositing it somewhere remotely, where I can’t accidentally delete it. I realize that GitHub should not be the end goal of code preservation, but as of yet I have not taken steps to preserve my code anywhere more permanently than GitHub.”

- “…’Sharing’, to me, means that somebody else can discover and obtain the code, probably (but not necessarily) along with sufficient documentation to use it themselves. ‘Preserve’ has stronger connotations. It implies a higher degree of documentation, both about the software itself, but also its history, requirements, dependencies, etc., and also feels more “official”- so my university’s data repository feels more ‘preserve’-ish than my group’s Github page.”

For more details and in-depth discussion on the initial research, the paper is available and open access here: https://peerj.com/articles/cs-163/. All the other related files to this project can be found here: https://yasmina85.github.io/swcuration/

—

Yasmin AlNoamany

New Resources in Literature

by Taylor Follett

Fall semester is always a time of fresh beginnings — new classes, new faces, and most excitingly for those of us at the library, access to new resources. We hope that the following new databases, books, journals, and much more will be of value to those studying literature. Here are some highlights for undergraduates, graduate students, and professors alike.