Author: pburnett

Berkeley Bustle, Fall ’23

UC Berkeley’s campanile sounding out the fall semester

Fall brings the bustle back to campus: the doubled traffic, the logistics planners, the events and grounds crews, the battalions of excited and brilliant first-year students. The bustle never left the OHC. We continue to push forward on a number of fronts, publishing oral histories, podcasts, and documentaries, giving presentations at conferences, and leading educational and public history work. But first, our fourth podcast season, Berkeley at 150: Let there Be Light, explores three different aspects of life at Berkeley: home, food, and studying hard. First-years to alums, feel free to enjoy in no particular order.

In August, we hosted our 21st Oral History Advanced Institute. With around fifty remote attendees from across the United States and around the world, we explored the A-Z of oral history, from theory and methodology to interviewing practices and options for archiving and interpreting interviews once they are completed. Most valuable of all, for us and for the attendees, was the workshopping of individual projects. Everyone came away with a richer experience of what it means to do this work! Watch our web space and our social media in early 2024 for next August’s institute.

Recently, we launched the UC Berkeley School of Public Health Oral History Project, which documents the changes and innovations the school has undertaken over the past twenty years. We’ve recently had the great fortune of interviewing some titans in the humanities and social sciences, exploring the relationship between a thinker’s lived experience and their ideas. Roger Eardley-Pryor interviewed famed environmental historian Carolyn Merchant, who is one of the key contributors to the domains of ecofeminism and feminist science studies. But more than that, it is nearly impossible to be an educated general historian without encountering her work in your formation and scholarship. Merchant and James Scott are two intellectuals who seem to transcend the notion of fields, whether traditional or new. It is rare to visit a scholar’s office or home, no matter what their discipline, and not see a copy of Scott’s Seeing Like A State on the shelf. Not only did Todd Holmes interview Scott and other scholars at the Agrarian Studies program that Scott founded at Yale, but he also produced a film about Scott, which is part of our ongoing work to make our interviews accessible and useful to educators, students, and the general public.

We’re putting the finishing touches on our first-ever exhibit in collaboration with The Bancroft Library, entitled “Voices for the Environment: A Century of Bay Area Activism.” Right across from our offices in The Bancroft Library, the museum space will feature audio from our interviews set to video of photos, maps, and more, while original paintings, murals, photos, posters, and pamphlets are displayed throughout the gallery space. There are also podcasts with more interview content for each section of the exhibit, all of which will be placed online as a permanent digital exhibition for the public to explore.

At the Oral History Association annual meeting in Baltimore, Roger Eardley-Pryor will present on a panel on the integration of audio and objects into public history and education work on October 19th. Amanda Tewes will be moderating that panel, as well as “Place-Based Oral Histories” on October 20th. Amanda also served on the OHA’s 2023 Program Committee. Shanna Farrell, who is on the Oral History Association Council, will be moderating the “Interviewing Dilemmas” panel on October 20th.

With the interviews for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project near completion, the interviewers recently collaborated with graphic artist Emily Ehlen and producer Rose Khor to build graphic-art pieces and a podcast derived from the interviews. We’re looking forward to their release.

Communications Director Jill Schlessinger asked student editors to reflect on the nature and meaning of oral history based on their experiences working with transcripts and conducting research at the center. Editor Adam Hagen also wrote a piece about Ernesto Galarza based on our interviews with the Mexican American educator and activist.

We’re continuing a lot of projects: on Japanese American intergenerational narratives, the East Bay Regional Park District, the Getty Trust, the San Francisco Opera, and the California State Archives. A host of new projects are coming this school year, from the California Supreme Court to cannabis genetics to the California Coastal Commission to more voices from UC Berkeley and the Bay Area science community. Stay tuned.

We wish everyone on campus and beyond a fantastic year!

Science in Context: The UC Berkeley School of Public Health Oral History Project

As we know from our daily experience of the COVID-19 pandemic, public health is a political and cultural flashpoint in American society, as it has been since its emergence as a field of study and area of state authority in the 19th century. Whereas conventional biomedicine situates illness squarely inside the human body — a matter of damage to or malfunction of organ systems — public health looks outward, to the communication of diseases among populations and to the social factors that contribute to health or illness. Public health practitioners look at everything from the aggregate of individual human choices, such as smoking, to larger, deeper historical structures in society, such as the impact of systemic racism on health outcomes. Is it the government telling you how you or your children should behave, or is it science-based advice to help reduce rates of illness, harm, or death in society? Public health is science in political context like few other fields of research.

Well over a decade ago, the School of Public Health at UC Berkeley began to take stock of this positioning and reflect on how a teaching and research institution could better respond to the challenges of science in context. This set of interviews emerged from an effort to document the recent history and institutional evolution of the school. Steve Shortell, who was dean of the school from 2002 until 2013, wanted to chronicle the foundation and growth of the On-campus/Online Professional MPH (master’s of public health) Program; the reinstitution of the undergraduate major in public health; the development of an office of diversity; a graduate program in public health practice and leadership; and a center for health leadership, formerly known as the Center for Public Health Practice and Leadership and currently known as RISE. Dean Shortell also wanted to feature some key leaders associated with these developments.

There are three interviews with Dean Shortell that provide the context for the institutional changes during this period, as well as explorations of his career in health management research. Executive Associate Dean Thomas Rundall was also interviewed about multiple initiatives, including his leadership of the graduate programs in health management and co-directorship of the Center for Lean Engagement and Research in Healthcare (CLEAR). Jeffrey Oxendine was interviewed about his role as co-founder and associate dean of the Center for Public Health Practice and Leadership, which began in 2008. Another feature of this oral history project was to explore the reinstitution of the undergraduate major in public health in 2003. Dr. Lisa Barcellos was interviewed in part about her leadership of that program and her research on the genetic and environmental factors involved in autoimmune disease.

There is also a set of interviews surrounding the establishment and growth of the online MPH program. Dr. Nap Hosang was the first director of the hybrid master’s of public health program, and he discusses the unique features of the program’s design, particularly with respect to accessing a diverse and unique pool of student talent, which contributed to the program’s success in subsequent years. Dr. Deborah Barnett was interviewed partly about her capacity as the successor and current leader of the program and as chief of curriculum and instruction. Alberta (Abby) Rincón recounted the history of her time as director of diversity and the foundation of the DREAM (Diversity, Respect, Equity, Action, Multiculturalism) office in the school. In her interview, chair of the Division of Community Health Sciences Dr. Denise Herd discusses the history of research in health disparities and the social determinants of health — a subject that is raised in many of the interviews — and her participation in the campus-wide Othering & Belonging Institute. Finally, Dr. Art Reingold was interviewed about his several decades as director of the Division of Epidemiology, the online MPH program, and teaching in the time of COVID.

If the field of public health is broadly defined as the study of health at the population level, this set of interviews reveals the broadest themes of health in context: the environment that shapes the expression of genes, the factors that lead to the nourishment or deprivation of bodies and minds, the factors that determine who gets to study or teach public health, the factors that shape the delivery of health care, and the contexts that shape the interactions between human bodies and other organisms and pathogens. The overarching story is about how these individuals studied, improved, and optimized institutional attention to these larger contexts, contributing to one of the most extraordinary public health programs in the country.

Read more from the individual interviews below:

Stanton Glantz: Putting Cardiovascular, Epidemiological, Economic, Political, and Policy Research into Action at UC San Francisco and Beyond

Today we announce the publication of the Oral History Center’s interviews with Dr. Stan Glantz. Dr. Glantz received his doctorate in applied mechanics from Stanford University before embarking on a multi-decade career at UC San Francisco. He contributed engineering concepts to cardiovascular research, biostatistics to epidemiology, and economics to the study of second-hand smoke and policymaking to regulate second-hand smoke, among many other research projects. The oral history explores his political and policy activism, the history of the clean indoor air movement, and his commitments to science and public health, in particular his long struggles with the tobacco industry and efforts to make UC San Francisco a world center for research into second-hand smoke, nicotine addiction, and the broader social determinants of health. His service to UC San Francisco and the University of California is also explored, in particular, his research and advocacy for policy changes on issues ranging from the rights of adjunct faculty to state funding of the UC system. These interviews showcase Glantz’s applied epistemology, his continual reflection on how knowledge is produced and shaped through formal and informal practices for arriving at scientific truth.

“Why Should We Share Anything with Them?!” – Oral History, Truth, and Ethics in Post-Totalitarian Societies

“It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable.” This quotation is part of a description of what we at the Oral History Center do. It sits at the beginning of every oral history we publish. It was written by Willa Baum, the longtime director of the Regional Oral History Office (the former name of the OHC until 2015). It highlights quite beautifully the conceptual foundation of modern oral history: the deliberate exploration of the unique, subjective historical truths of individuals. While oral history was once considered a poor evidentiary cousin to official records stored in archives, academic oral historians from the 1960s on proclaimed proudly the value of subjective evidence. It was the subjectivity itself that was to be recorded and studied. At the same time, oral historians promised to expand the archive by interviewing people whose views had not been recorded in archives or studied by historians. So, there are two related ideas: oral history as a practice of inclusion that diversifies and enriches the archive, and a belief that the historical record can be made more accurate, more true, by conceiving of it as a living, evolving, contentious space in which there is little in the way of a settled, single consensus about what actually happened. “What actually happened” is a translation of a phrase coined by German historian Leopold Von Ranke, who regarded government documents as the apex of authoritative sources because he saw the 19th-century nation state as the prime mover of history. When I took historical methods courses ages ago, this phrase was trotted out by professors as a particularly primitive, dated, and possibly morally bankrupt form of reasoning. History is about power, the professors would argue, written by the winners, erasing the views and the experiences of the excluded. What mattered in modern historiography was making sure that different experiences and viewpoints were represented in the historical record, and in the interpretations of the historical record.

Recognizing that history is about power, oral historians evolved practices for sharing authority with interviewees, whom we in the field refer to as “narrators” to highlight their authority as originators of a narrative, as opposed to passive sources for an interview. Sharing authority might involve planning an interview far in advance with the narrator, apportioning time to topics, putting up guardrails, and sharing the text of the transcript after the interview to permit them to reflect on their own words and correct them if necessary, or to protect themselves or others from anticipated harm. I call this process the construction of the “deliberate self.” With all the pressure and stimulation of undergoing a recorded interview in real time, even the most seasoned and trained speakers can, in a moment, misrepresent themselves, speak in a disorganized fashion, and mischaracterize what they remember. This is the spontaneous self. To be ethical, and above all trustworthy, interviewers should give narrators the opportunity to see themselves in their own words and refashion them to better represent themselves and the past for posterity. This works well if oral historians are already aligned more or less with their narrators with respect to what is known and how what is known is understood. This “shared authority,” to use oral historian Michael Frisch’s term, is part of what practitioners call the co-construction of oral history.

But what happens when a single, official narrative of state history is washed away by a revolution, and what remains is the collective trauma of decades of misinformation, surveillance, and punishment? How does one conduct interviews in this space? More importantly, how does one interpret what is said?

Over the past four years, I have conducted interviews with a group of Czech physicists. This project evolved into an exploration of how a scientific community functioned under a totalitarian order. The Czechoslovak Academy of Science and courageous scientists emerged as important spaces and agents that supported intellectual diversity and underground political activism. Scientific orientations and a certain form of asceticism underpinned political activism against dogma, propaganda, and the repression of fellow scientists and citizens. These interviews highlighted the contributions of scientists to the underground political movements established before the Velvet Revolution and to the democratic political order that followed.

Why was I doing this research? I study “scientists in trouble.” I am interested in the ways in which a scientist’s commitment to objective truth – a truth completely separate from the background, ideology, beliefs, and values of people – plays out in the messy political world in which scientists must live and operate. What happens when an individual scientist’s commitment to scientific truth clashes with powerful political forces? It could be the Iowa dairy industry during World War II or the Communist Party in Czechoslovakia. In the latter case, what is the relationship between a scientist’s commitment to objective truth and the demands in a totalitarian society of an absolute commitment to dogma? In my conversations with these narrators, and with scholars and students in the Czech Republic, I was confronted by a different understanding of the value of oral history from what we have constructed in the United States and a few other countries.

Last fall, I conducted two workshops on oral history methods, for faculty and oral historians at the Czech Academy of Sciences in Prague and for graduate students at Masaryk University in Brno. My primary motivation for doing this work was to use oral history to meet the challenges of a difficult past and of an increasingly difficult present, one in which state-sponsored versions of the truth pose grave threats to democracies in Central and Eastern Europe. I was also considering the value of oral testimony in the historical shadow of a police state, where many official records from the totalitarian period have now been destroyed. Finally, I wanted to share ideas about the role of trauma in these stories – the difficulty of telling stories that, to this day, are not supposed to be told in Czechia.

But it was when I came to lead the training in Brno for graduate students in a history department that I learned about the implications of a particular form of collective trauma for the practice of oral history with populations who lived under or in the shadow of totalitarianism. After I explained the involved process of co-construction of an oral history from beginning to end, the importance of sharing transcripts with narrators, for example, a hand went up. “My adviser told me not to share the transcripts with the narrators.” Why? Part of the project this student was undertaking was to interview former members of the Czechoslovakian secret police. I said to the class that transcripts should be shared with narrators if possible. The student replied, “Why should we share anything with them? We give them more consideration than they ever gave us!” I trotted out my explanation of the “deliberate self.” Another student spoke, “If you say something in court, it’s in the record forever. You can’t erase it.” Still another said, “If you give them the opportunity to see how they really look, they will cut everything of any historical value out, and we will have nothing!”

I took my time to respond. “This type of interviewing will work, exactly once. But when you break trust with narrators, the reputation of your process, and those of anyone else claiming to do oral history, for that matter, will be tarnished in direct proportion to the notoriety of the exposure of the narrators’ hidden stories.” (Full disclosure, I said this at the time much more awkwardly than what I wrote here, but I am asserting my prerogative to reconstruct my narrative.)

The discipline of oral history relies on multiple narratives to tell a composite, textured story of perspectives about how complex phenomena can be understood, and framed. It was oral historians from Italy, a nation with a comparably complex political history as Czechoslovakia’s, who helped shape the field of modern oral history. For Alessandro Portelli and Luisa Passerini, oral history was the analysis and interpretation of the complex interplay between memory and recorded history. Portelli studied collective memory and press reports about labor protests in Italy. He wrote about how narrators transposed the death of a protestor at the hands of the police to a different protest about a different cause that actually happened four years later. Passerini wrote about the deafening silence in the life histories of those who described a “before” and an “after” of the Italian fascist period.

With these kinds of approaches in mind, I offered some suggestions to the Czech students. If you are disturbed by what you perceive as false narratives, lies to whitewash the narrator’s complicity in an evil political order, you can do at least two things. You can interview those who suffered at the hands of the police, explore the consequences of surveillance and interrogation on families of the suspected and accused, and/or you could also serve as a trustworthy partner of narrators whose deeds and perspectives you find abhorrent, but in the process potentially produce a more candid text than might otherwise be obtained through spontaneous revelations in some kind of interview trap. Then, you could interpret the alignment and differences among those perspectives. Allowing these perspectives to talk to one another through your historical interpretation is one way to understand oral history work.

So, were these graduate students chastened and enlightened, having been brought up to date on the latest best practices in oral history from the United States via postwar Italy?

Not necessarily.

The modern oral history method, this careful co-construction of the story between interviewer and narrator, is in my opinion the best way to interview the survivors of trauma and to collect and archive their stories. It gives the narrators control, the absence of which is at the center of trauma, which offers the potential to be a salve for the wounds of the past.

I wonder, however, if there isn’t some kind of American exceptionalism, or Italian exceptionalism, to this version of oral history practice. The evolution of the discipline or practice of oral history is towards diversity and inclusion, both in terms of sources of narratives and the ways in which narratives may be cultivated, framed, archived, or disseminated. Truth is plural, and the plural truths stand in contrast to one another. It’s a model of history as mosaic, not a king’s chronicle. In fact, the value of oral truth is that it comes from a narrator, filtered by the narrator’s history, memory, background, and position in the world.

When I did my initial interviews for the Czech physics project, one thing that struck me was that, of all the books smuggled into Czechoslovakia, the most important to this group was the works of Karl Popper. Karl Popper is a philosopher, known in some sectors of the academy for his rigid definitions of the mechanisms of science and the nature of scientific truth. More recently, some historians have pointed to Popper’s right-of-center political commitments as evidence that a belief in positive knowledge independent of the knower – that is, a truth that is not a matter of perspective, of background, or of prior knowledge – is a tool and a smokescreen for right-wing hegemony.

And yet, the people’s struggle, in Czechoslovakia, the poet’s revolution of Vaclav Havel, was fought by people who took this definition of truth as their north star. It is not hard to understand why.

It is not just the narrator who is traumatized in the Czech Republic, and so many other places; it is an entire society. The source of the trauma is more than the narrator’s experience of a lack of control in their past; it is the fundamental interdiction of independent meaning-making that is the lifeblood of a totalitarian state. It was the insistence on a daily truth that brooked no examination, discussion, or independent verification that so scarred those who are trying to tell their stories in Czechia now. One of the critiques of social science and humanities research is that the instrument of knowing cannot really know itself. How can humans really know humans the way we measure the chemical composition of matter? But that kind of objective clarity is in a way what these young historians in Czechia want. The heat of this discussion came in part from the problem of interviewers interviewing other interviewers about their interviewing practices. Oral history practice evolved partly in response to the historic menace of the interview: the confession, the interrogation, the Inquisition, self-incrimination through recorded, and always in some way compelled, speech. The tables turned, the student viewed the formerly powerful as liars, now minimizing, erasing, or justifying their practices as police interrogators. Is historical truth here a salve or a weapon? Can it be both?

It is often said that testimony about trauma has been a path to healing. Witness the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa in the 1990s (though the results of that process are still being evaluated). But what if a society is still very much stuck on the truth part? One of the students came up to me after the workshop and apologized. “I don’t think we as a society are ready yet for your high ethical standards.” There was not a hint of sarcasm in his statement, though maybe there should have been.

This encounter with post-Velvet Revolution graduate students in Czechia did not change my mind about current oral history best practice as I understand it. Making the narrator feel safe and in control is the best guarantor of their representation of themselves and what they experienced. But in our search for plural truths, we need to respect the fact that one person’s truth is often a claim to “capital T” truth, not a perspective or opinion, and that their participation in an oral history project can be part of their battle against obfuscation, propaganda, erasure, and lies. That goes for both the narrator and the interviewer. So we need to be careful when we consider the epistemology of oral history, and reflect on what objective truth means to many individuals and communities, as a matter of cultural and actual life and death. And we might further consider the extent to which our commitment to co-construction shapes both the archive and a historian’s interpretive freedom. If trust-as-alignment is paramount, how much room is there for skepticism, comparison, or independent evaluation? Fortunately, oral history is an evolving field, and it is through these encounters with meaning-making in different contexts that we stumble towards our provisional truth of what we think we know about ourselves and what we do, much as Karl Popper once claimed was the ideal practice of science.

Celebrating the 100th Anniversary of San Francisco Opera

It is with great pride and pleasure that we announce the launch of four new oral histories with San Francisco Opera, continuing a collaboration with the Oral History Center that reaches back decades. In 1973, interviewer Suzanne Riess sat down for interviews with Julian Bagley, who met H.G. Wells and Marian Anderson during his forty years working at the War Memorial Opera House from its opening in 1932! In 1999, Oral History Center interviewer Caroline Crawford conducted an oral history with tenor, voice teacher, and impresario James Schwabacher, whose relationship with San Francisco Opera went back to the 1940s. The San Francisco Opera has benefited from very stable leadership over the past century, with only two general directors during the first sixty years of its existence. This oral history project gained momentum in the 1980s with a three-volume oral history with Kurt Herbert Adler, who was general director of the Opera from 1953 until 1981, and those who knew and worked with him.

In the 2000s, Crawford conducted a number of interviews documenting the conception, creation, planning, management, rehearsal, and performance of an opera commissioned by the Company, John Adams’ Dr. Atomic. For the oral history project Doctor Atomic: The Making of an American Opera, Crawford interviewed composer John Adams, general director of the San Francisco Opera Pamela Rosenberg, music director Sir Donald Runnicles, who conducted the world premiere, music administrator Clifford “Kip” Cranna, and chorus director Ian Robertson. In 2011, Crawford created and oral history with star mezzo-soprano Frederica “Flicka” von Stade, exploring in depth a career in opera performance.

In 2018, we undertook dramaturg emeritus Kip Cranna’s oral history, this time to capture his long career with the opera as a music scholar/ administrator and dramaturg, including his familiarity with the tenures of general directors Kurt Herbert Adler, Terence McEwen, Lotfi Mansouri, Pamela Rosenberg, and David Gockley.

The oral history with general director David Gockley (2006-16) showcased his transformative promotion of “American music theater” that he had pioneered at the Houston Grand Opera. In his time at San Francisco, Gockley focused on dissolving the boundary between opera as high culture and a more democratic and inclusive notion of music theater. He was also an important impresario of new, original compositions by American composers, often in American historical settings.

The oral history with general director Pamela Rosenberg (2001-2006), Gockley’s predecessor, revealed a different approach to opera administration. Although raised and educated in Venezuela and California, Rosenberg spent her entire career in opera administration in Europe, and brought a European sensibility and enthusiasm for adventurous productions to San Francisco. As she began her term in 2001, Rosenberg faced the impact of 9/11 and the dot.com recession. Despite these challenges, she pressed forward with high-risk, high-reward premieres and productions.

The Oral History Center also explored the intersection of San Francisco Opera with the broader community in an interview with Opera Board member Sylvia Lindsey. She was asked to join the Opera Board in 1987, and since then has held a number of positions on committees, in particular to do with education and outreach. She has been a vital force in bringing young people to the opera, but she also fostered inclusion and belonging among the staff and visiting musicians and performers, long before these terms came to stand for common institutional practices. The interview touches on her multiple roles with several arts organizations, highlighting a key facet of her importance as a connector, bringing different people together towards a common purpose.

The pursuit of an art form that is hundreds of years old in the world center of up-to-the-minute technological trends and innovation may seem to be paradoxical, and even a bit quixotic. But the San Francisco Opera is an American story of modernity, resilience, and adaptation. It is about the transplantation of cultural forms from Europe, nurtured early on by many Italian immigrants to the city. It is also about would-be performers growing up in smalltown USA, seeing Beverly Sills on late-night talk shows, and wondering if they too might one day undertake something so grand and beautiful as a calling. But it is also about the ways in which art forms and their institutions can signal and in some ways exemplify elitism, and the efforts of the Opera to move beyond this unintentional cultural positioning through outreach, education, and initiatives of inclusion and diversity. Ultimately, these stories are about broadening the idea of what opera can be, for the performers, for the audiences, and for young people who talk to a singer who visits their schools, attend a performance, see themselves represented on stage, and perhaps dream one day to perform.

This most recent set of interviews is an in-depth exploration of what it means to do art. Creativity is of course the lifeblood of composition, performance, production, and, dare I say, administration. But this project is very much about the drama of the work of performance in all its dimensions. The audience experience of opera performance is certainly visceral. Those soundwaves hit you in your chest. You are, after all, sitting inside the giant horn that is the War Memorial Opera House. The melodies and harmonies open your heart, and the dramatic performance threatens to break it. But what emerges after talking for hours with people who make each of those performances work flawlessly every night is that this art is constructed and expressed on a knife’s edge. The stage manager’s calls sound like an air-traffic controller calmly landing dozens of jets at once. A prima donna falls sick the day of, and a cover, or understudy, steps in to sing a four-hour opera. Many, many things can go wrong at any moment, but the audience experience is only a musical and dramatic catharsis. Radiate out from the excitement behind the scenes of every performance, and you can see the larger drama in which the Opera finds itself: the ups and downs of the market and the tragedies of war and disease that impact the Company, its audience, and the wider community. In short, these interviews are very much about what art means, now and for the ages. For the past one hundred years the San Francisco Opera has been making meaning and beauty for its evolving communities. May it continue to do so long into the future.

The Occupational Hazard

When people talk about becoming fast friends with someone, they often describe the experience as an easy ability to discuss anything, even the proverbial meaning of life. It’s a sign of a strong bond that you can feel vulnerable enough to share what you really think of life and how it has been lived.

What happens when it is your job to talk about the meaning of life with someone, to walk with them through the years as they take stock, evaluate failures and triumphs, and provide the odd piece of advice along the way? I would say that that is a pretty amazing job, and it is. But you also realize that one reason you are interviewing many of these folks is because they are nearing the end of their journeys. You become fast friends — one could say lifelong friends — and then, one day, they go away.

Interviewers have loss as their occupational hazard. Many of the narrators I speak with are in the late 80s, early 90s when I first sit down with them. Then it might be another twelve-to-eighteen months of interview sessions, breaks for illness and life events, reviews of transcripts, assembly of materials, publication, and even follow-up projects such as podcasts or additional interviews with others. Then – not always, but often – there are check-ins, updates, exchanges over a few years, often about more of the same: what things mean, what is important, the imperative of what we ought to do and the burden of what we often do instead. Of course, it’s important to realize that the temporary nature of our residence here is what gives life its eternal meaning. I watch people enact this understanding as they outline who they have been, who and what they have cared about, what they have witnessed, and what all this might mean for the future. But the fact is that the people I talk to become a part of me, and their departure takes my breath away, every time.

The consolation is that, if one has lived to the ninth decade, it is a kind of triumph to be celebrated and contemplated. I’m 52 years old. Although time is marching along, I am still usually at least a generation younger than the narrators I interview. Without getting analytical about it, there is just something elemental about an older and a younger person talking together. If, in general, our society suffers from too much talking and too little listening, it is especially true that we do not listen to older people often and carefully enough. An older person’s perspective is not just any perspective; it is the wisdom of a survivor. They have a visceral experience with life’s cycles and events of all kinds. Plugging into that way of knowing in these interviews is a gift. And while there is contemplation of the inevitable tragedies of life in these oral histories, and the eventual passing of these storytellers is sad, it is not usually tragic. So, accompanying a feeling of loss is a sense of gratitude and happiness that they lived a meaningful life with purpose and dignity.

I have been interviewing in earnest for about ten years, and my personal in memoriam list has increased with almost actuarial precision in 2020, 2021, and now this year.

In April, there was a memorial for economist George S. Tolley, with whom I spent a few weeks in Chicago in 2018, where I had a balcony view onto how sub-disciplines in economics developed around social and political problems: urban sprawl and housing costs, the pricing of environmental policies, economic development initiatives, and new ways of valuing health. He was 95.

In July, oral history impresario Tony Placzek passed away after spending the last four years of his life building two oral history projects, one about his dramatic family history and the other about underground political activism among physicists in Czechoslovakia. He was an inveterate optimist and a good friend. He was 83.

I first met Lester Telser at an event at which Nobel-Prize-winning economists fawned over his mathematical prowess in the jovial “taught me everything I know” manner of close mentees. He had little patience for dogma of any kind and was remarkably kind and generous of spirit. Talking with Lester was a master class in the importance of appropriate expertise and good judgment in the face of enormously complicated societal problems. As late as this summer, Lester and I were swapping tips on good papers and the hidden heroes of baroque chamber music. He died in September. He was 91.

I only met Thaddeus “Ted” Massalski briefly at a conference at Disneyworld, of all places. He talked about his incredible career as a professor of metallurgy and materials science, his key scientific discoveries and his experiences as both a refugee and a soldier during World War II. Here Professor Massalski tells the story of a narrow escape from the Nazis during World War II. He was 96.

Although I did not interview the following personally, we have lost some important friends to the Oral History Center this year: narrators and supporters Richard “Dick” Blum and Howard Friesen. Mr. Blum was a financier, former Regent of the University of California, and supporter of many causes. The Carmel and Howard Friesen Prize in Oral History Research is awarded to an undergraduate whose outstanding paper utilizes the OHC collection. From our Regional Oral History Office community (renamed the OHC in 2015), we also lost interviewer, US political historian, and composer Julie Shearer.

For many people, the holidays can be hard for a number of reasons. One reason may be that they are a time of reflection and meaning-making, maybe a little bit like undertaking an oral history. Fortunately for me, mine involve bittersweet emotions this year. I feel lucky to have known the people who passed this year and sorry to have missed knowing the others. So, this season, I wish you peace with the difficult memories and joy with the creation of new ones with family, friends, and even the fast friends and acquaintances you have just met.

The Power of Stories

February 24th, 2022 was a date I was looking forward to, from a bureaucratic perspective. It would mark the transition to a new role here at the Oral History Center as the Interim Director. Of course, it was impossible to ignore the anxiety building about Ukraine. Even though predictions were made by many sources well in advance, the arrival of the world’s most recent invasion was no less shocking.

The invasion of Ukraine on that day was shocking. Its scale and horror were surprising to many of us. But it was not an unfamiliar story. The experience of invasion is a story often told, and it is stories, first-hand accounts, that are galvanizing tremendous worldwide support for Ukraine in this war. The power of these stories is also evidenced by their absence from the official state organs of Russia’s media, by the slippage of individual moments of protest past the censors, scrawled posters behind the measured tones of the polished presenter, by emails and texts to individual Russians from around the world, fragments of stories, coming one at a time.

Oral history in its modern form coalesced in the 1960s as a movement and an association to document the lives, experiences, and views of ordinary people, with a democratic ethos at its heart. The basic idea was that if you collected, archived, and published multiple stories from individuals and representatives of communities, they could stand in contrast to the single narrative of any social system — an institution, a government, those authorized to speak on behalf of others — which represents a tempered, aggregate, vetted version of the truth, one that may obscure or distort more than it reveals. The truth of one person’s experience is always partial to that exact extent. The collection, archiving, and sharing of multiple perspectives, it is hoped, is an incomplete antidote to conventional wisdom, dogma, propaganda, euphemism, and erasure. To the extent that these stories can be preserved, they promise to outlast the dominant truth of any particular group or era.

The theme of this year’s annual meeting of the Oral History Association is “Walking Through the Fire: Human Perseverance in Times of Turmoil.” I wish I could say the theme was prescient, but these days it is just a good title for where we are at this moment in history.

This theme and this war spark memories of interviews I’ve done over the years. Materials scientist Ted Massalski recounted his narrow escape as a boy in Poland in World War II, sandwiched between the occupying Nazis and the advancing Soviet Army. In another oral history, engineering scientist George Leitmann told me what it was like to see the Nazis roll in to Vienna in 1938. There are many other stories of the survival of invasions and evacuations in our collection, including from Russian emigres who fled the Soviet Union, from former UC Berkeley Chancellor Chang-Lin Tien or restaurateur Ceclia Chiang, who escaped war-torn China, or economist John Harsanyi, who escaped from Soviet-occupied Hungary after World War II.

Before the pandemic, I completed a project on physicists who lived through the communist period in Czechoslovakia. Speaking from the land of Franz Kafka, they described the risks of running afoul of the state while running an “underground university,” which hosted secret political discussions of smuggled forbidden texts in the 1970s and 80s, and which paved the way for the turn toward democracy in the early 1990s.

Some of these Czech narrators believe that the threat of totalitarian control never really went away in that region, and for that reason remained vigilant. I was heartened and humbled by their swift action in the face of the invasion, their efforts to influence the Russian government to reverse course, and to help incoming refugees from Ukraine. Their stories will hopefully inspire the current generation of Czechs to defend their hard-won freedom.

What makes suffering so unbearable is when it is by design. In the strategy of total war, only most recently manifested in Ukraine, the burden of injury, death, destruction, division, and separation of loved ones is planned to produce a desired outcome: the conquest of territory in the most brutal terms, but also the achievement of enforced conformity, complicity, resignation, and humiliation of the recipients of this terror, in short, dehumanization.

What can make suffering more bearable, at least from my experience interviewing people who have passed through terrible events, is when the subjects of such terror bear witness to what they endured, name it, and pass the stories of loss and survival to others as a testament to their resilience and humanity. Storytelling, in the face of dehumanization, can promise a rehumanization, of those who survived to tell the story, those who did not, those who hear the story, those who keep it, and those who pass it along.

Of course, this most acute crisis, this war, requires direct and immediate action. Part of this action is a commitment to the expression and dissemination of narratives of multiple, diverse experiences, in Ukraine, in Russia, and everywhere a single voice threatens to silence all others. As gutted as I am by the horror of this war, I do find hope in the assistance provided to many millions of those who are suffering. The stories circulating about the plight of Ukrainians are aimed most urgently at stopping the war; but they are also, I think, about spreading the load of grief and loss to any and all who will listen. They indicate what is most powerful about oral history. Stalin is reported to have said, apropos of the deliberate starvation of millions of Ukrainians at the beginning of the 1930s: “If only one man dies of hunger, that is a tragedy. If millions die, that is only a statistic.” Apocryphal or not, the statement expressed well the numbing effect of brutality at scale. But a story is not a list of numbers; it is the meaning of an experience to an individual. Oral testimony counters the enormity of Stalinist terror with an individual experience and perspective, amplified by the number of listeners, readers, and repeaters, each connected to one person’s visceral truth.

From the OHC Director: The Gift of Being an Interviewer

The Gift of Being an Interviewer

From years of listening, I’ve learned that we all want to tell our stories and that we want, we need, to be heard.

After close to nineteen years with the Oral History Center — ten of those years serving in a leadership role — I have decided to hang up my microphone and leave my job at Cal. As with any major life transition, reflections naturally pour forth at times like these. I’ve been keeping track of these thoughts in hopes that they might prove interesting to others who have spent so many hours interviewing people about their lives or those who are interested in oral history writ large.

For me, learning and practicing oral history interviewing has been a gift. It has made my life richer, allowed me to access insights about human nature that otherwise might have been hidden from me, and offered me the opportunity to see people as the individuals that they are, freed from the stifling confines of presumed identities and expected opinions.

At OHC, interviewers typically work on a wide variety of projects. We often interview about topics in which we do not already have expertise and thus must develop some fluency with something new to us. Because we contribute to an archive that is to serve the needs of an unforeseeable set of current and future researchers, we naturally interview people who have made their mark in very different fields. This means that we interview people, sometimes at tremendous length, who are not like us and whose life stories and ways of thinking might be very different from our own. There is a well-documented tendency among oral historians to interview our heroes, people whose political ideals jibe with our own, people who can serve protagonists in our histories, people whose voices we want to amplify. At the Oral History Center, this bias is not paramount — rather, we strive to interview people across a broad spectrum of every imaginable category. And while we almost always end up very much liking our interviewees, they need not be our personal heroes and are not required to share our opinions; they only need to be an expert in one thing: their own lives and experiences.

This way in which we do our work has sent me wide and far and exposed me to a profound diversity of ways of looking at the world. And this multiplicity of perspectives has informed, challenged, engaged, astounded, and, frankly, remade me again and again over the past two decades. It is this essential facet of my work that I consider a gift to my own life.

After having conducted approximately 200 oral histories, ranging in length from ninety minutes to over sixty hours each, I find it a tad difficult at this point to highlight some interviews and not others. Whenever I get asked (as I often do): what was your favorite interview? I used to wrack my brain, endlessly scrolling through all of those experiences, but now I usually just say, “my most recent oral history.” I offer that up because the latest one typically remains most fresh in my own (not always so robust) memory — it is the interview that still retains much of the nuance, content, and feeling for me and that’s why it is “the best.” Still, I want to offer up a few examples from some of my oral histories to show how interviewing has influenced the way I live in the world.

Moving beyond my comfort zone

I arrived at OHC in July 2003, first spending a year on a fellowship in which I was given the opportunity to finish my book manuscript, Contacts Desired (2006), and then in July 2004 I started as a staff interviewer. My areas of expertise were social history, the history of sexuality and gender, and the history of communications. My first major oral history assignment? A multiyear project on the history of the major integrated healthcare system, Kaiser Permanente. Not only was this topic well outside my area of expertise, it also was not intrinsically interesting to me. But this was a new job and a big opportunity, so with an imposing hill in front of me, I decided to climb it. The project went on for five years and during that time I conducted most of the four dozen interviews. The topics ranged from public policy and government regulation to epidemiological research and new approaches to care delivery. I was sensitive to my inexperience with the subject matter so I hit the books and consulted earlier oral histories. I worked hard to get up to speed.

Just a few interviews into the project I had what might be considered an epiphany. After years of studying historical topics that were familiar to me, even deeply personal, I was pleased to discover something new about myself: I loved the study of history and the process of learning something new. Period. With this newly understood drive, I pushed myself deeper into the project and, I hope, was able to be the kind of interviewer that allowed my interviewees to tell the stories that most needed to be told. As it happens, along the way, I learned a great deal about a topic — the US healthcare system — that is exceedingly important, extraordinarily complex, yet necessary to understand. When the push for healthcare reform burst through in 2009 and 2010, I felt informed enough to follow the story and to understand the possibilities and pitfalls endemic to such an effort. In short, if one is open to the challenge, oral history can significantly broaden one’s horizons, educating one in critical areas of knowledge (from the mouths of experts!), and it might even make one into a more informed citizen.

Questioning what I thought I already knew

The Freedom to Marry oral history project was in many ways the opposite of the Kaiser Permanente project. First off, I could rightfully consider myself an expert in the history of the fight to win the right to marry for same-sex couples and the broader issues surrounding it. After all, I had written a book on gay and lesbian history and had personal experience with the movement when I married my partner in February 2004. Moreover, in graduate school and in preparation for writing my book, I had closely studied the history of activism and social movements. I had gone into this project, then, thinking I had a pretty good idea of what the story would be and what the narrators might say on the topic: this would be another chapter in the decades-long fight for civil rights in which activists engaged in protest and direction action, spoke truth to power, and forced the recalcitrant and prejudiced to change their minds.

From fall 2015 through spring 2016, I conducted twenty-three interviews with movement leaders and big-name attorneys, but also with young organizers and social media pros; I interviewed people in San Francisco and New York, but also in Maine, Oklahoma, Minnesota, and Oregon. What I learned in these interviews not only made me greatly expand my understanding of the campaign for marriage equality, these interviews also forced me to revise my beliefs about social movements and how meaningful and lasting social change can happen (I write about this more here). As a result of this project, I came to believe that some forms of protest, especially violent direct action, are almost always counterproductive to the purported aims; that castigating people with different ideas and perceived values is wrong and likely to produce a long-term backlash; and that in spite of our differences of opinion on contemporary hot button social issues, the majority of people cherish similar core values — values that bind rather than separate. The interviews demonstrated that by focusing on the shared values, rather than hurling epithets like “homophobe!” or “racist!” at your opponents, the ground is better readied for future understanding to grow. The history I documented surely is more complex than this, but these observations are true to what I found and are a necessary part of the reason this particular movement succeeded as well as it did. Through the Freedom to Marry oral history project, I learned to question the accepted public narrative and even what historians think that they knew on a topic. I recognized that openness to new ideas is a prerequisite of good scholarship. I recognized that most of all I needed to listen to what the oral history interviewees said and to compare that to what I thought I already knew. As a result, I learned to not let what I thought I already knew determine what I could still learn.

Telling a good story

The oral history interview is a peculiar thing. As ubiquitous as interviewing seems today, from StoryCorps on NPR to countless podcasts featuring interviews around the world to articles in the biggest magazines, the classic oral history method as we practice it at OHC is still quite rare. For our interviews, both interviewer and interviewee put in a great deal of effort in terms of background research, drafting interview outlines, on-the-record interviewing (often in excess of 20 hours with one person), and review and editing of the interview transcript. As a result, our interviews are almost always excellent source material for historians, journalists, and researchers and students of all stripes. But what moves an oral history from “good documentation” to something more is often the quality of the storytelling. Certainly some people, as a result of special experiences, have more fascinating stories to tell than others, but everyone I’ve ever interviewed has many worthwhile stories to tell: from formative family dynamics while young to the universal process of aging.

The difference between a competently told story and an engrossing one isn’t necessarily the elements of the story but the skill and verve of the storyteller. To hear Richard Mooradian, for example, speak about his life as a tow truck driver on the Bay Bridge and tell what it’s like to tow a big rig on the bridge amidst a driving rain storm is, yes, to learn something new but, more, it is to gain insight into a personality and the passion that drives that person to do what he does. I eventually learned (maybe I’m still learning) that when someone begins a story — and I know now the difference between a question being answered and a story being told — it is time for me to shut up, actively listen, and be open to the interviewee to reveal something meaningful about themselves. After years of helping, I hope, others give the best telling of their own stories, I started to think about my own stories, both the stories themselves but also how they have been told. I’ve come to think that these stories are nothing less than life itself: they are the emotional diaries that we keep with us always and, if we’re good, are prepared to present them to friends and strangers alike. From years of listening, I’ve learned that most of us want to tell our stories and that we want, we need, to be heard. This is a deeply humane impulse and I like to think that nurturing this impulse is at the core of what I’ve learned to be of true value over the past two decades.

These three lessons — openness to moving beyond your comfort zone, questioning what you think you already know, and telling a good story — are not necessarily profound or new. For me, however, they are real and as I return to them regularly in my work and personal life, they have been transformative. They have been a gift. The world of knowledge is massive. Learning something new is a key part of this gift. I’ve long recognized that we live in a world of Weberian “iron cages,” siloed into separate tribes. Listening to my interviewees challenge accepted wisdom inspired me to buck trends, forget the metanarratives, and break free from those cages confining our intellect and spirit. Stories are the most precious things we can possess. Create many of your own and share them widely – and wildly. After close to nineteen years at the Oral History Center, I am departing to do just that: to focus on living new stories and ever striving to tell them better.

Martin Meeker

Oral History Center

Director (2016-2021)

Acting Associate Director (2012-2016)

Interviewer/Historian (2004-2012)

Postdoc (2003-2004)

OHC’s November 2021 Director’s Guest Column: “Power, Empathy, and Respect in Oral History” by Paul Burnett

“So oral history is interviewing.” I get this a lot from people who are trying to understand what I do for a living. Yes, the interview is the primary way in which we gather our historical data, our stories. When people think of interviews in general, however, they might think of the police interrogation, the oral examination in schools, the journalist’s scoop, even an anthropologist’s study of a community, amongst other examples. Near the end of his life, philosopher Michel Foucault was hoping to do a large research project on the interview and the examination as sites of power relations. He could not have been more astute. In each of the examples above, control rests almost completely with the interviewer. The interviewers extract information from the narrator for their own purposes, often without consideration of the interests of the narrator, and sometimes directly against their interests. Sometimes narrators are allowed to see the resulting work; often they are not consulted.

By contrast, oral history as a disciplinary academic practice and as a social movement begins and ends with the problem of power. It’s not that we can get rid of power; power is interwoven through our relationships. Oral history methods acknowledge power relations as a problem to be managed, helping to ensure that the narrators tell the stories they want to tell. We begin with a process of informed consent, so that narrators know what to expect from beginning to end, and that they have the power to withdraw from the work at any moment, even after the project is finished. We then engage in a period of planning and research. Although a spontaneous, cold interview might seem more authentic, what happens in those cases is that the narrator is often at sea in their memories, their real-time decision-making about how to present themselves, and their anxiety about which stories to tell, in how much detail, and with what words. And then we are right back to the problem of the interviewer controlling the scene. By collaboratively planning in advance, the narrator and interviewer build a bond of trust and a plan around the nature of the storytelling.

And when the interview happens, we can both relax, and that’s where it becomes spontaneous. I call it “planned spontaneity,” with a heavy debt to Miles Davis’ approach to “controlled freedom” in jazz performance. Telling a story is like singing; it is singing. It can be an emotional performance of your deepest truths. I’d be tempted to say that the interviewer is the impresario in this metaphor, arranging things so that the narrator’s story shines. But my ideal role would be to serve as both the room and the audience, to let the narrator hear their own voice reflected from the back of the hall, and to see and sense the audience’s engagement with the performance. Ask any singer, and that’s what they need for a good performance; they need feedback from the audience and to hear their own voices.

That’s why, during the interview, I “read back” what I’m hearing periodically to give real-time feedback. But we also transcribe the interview so that the narrator can review what they have said and decide if that is the final form of the story, making changes as needed. Then we ask them to sign off on the finished product, with some guarantee of access to the narrator and their communities. All of these practices together form a set of protections that maximize the narrator’s power in forming, telling, and preserving stories for the future.

The problem of power might be mitigated by this set of practices, but power is always unfinished business. There is the history of the interview itself, whose reputation for extraction, exploitation, and manipulation is not lost on many communities. There is the university, a site of state, political, and economic power, and the authority to include or exclude that hangs over the interview. Anthropologist Michel Rolph-Trouillot wrote about the ways in which the decision about what gets included in archives is the first and perhaps most important violence done to history. Narrators and interviewers come to the interview within multiple, overlapping sets of power relations, exclusions, and hierarchies that threaten to distort and even block trustful communication.

For the interviewer’s part, there are two basic orientations that help with – but do not solve – these problems. The first is empathy. I have interviewed a lot of powerful people, people who might seem from a distance invulnerable, privileged, at ease. I hate to sound obvious, but everyone has experienced exclusion, denigration, and trauma of some kind in their lives, often of many kinds. Sometimes exclusion is a source of pride; but it is most often a source of pain. I have a lot of power and privilege, but I can tap into experiences of the exercise of arbitrary authority, exclusions, bullying, violence and trauma in order to attempt to connect to those who have experienced far greater violence, who have lived lifetimes inside social structures of exclusion and trauma. But if we amplify voices of the excluded, we have to understand that connecting and collecting can too easily end up as claiming and taking.

Empathy is only one part of it. That assumption of some kind of access to another’s experience is another problem of power and privilege. Interviewers also have to begin with the assumption that vast oceans of human experience elude them. Research can help, but a fundamental orientation of humility and respect is required to establish a bond of trust with a narrator. Is there some core of human experience that we all share? Of course. But history shunts us all into patterns of human experience that are both radically different and arranged in a long list of intersectional hierarchies of arbitrary value – race, class, gender identity and orientation, citizenship, disability, body politics, and surely more structures which we as a society have yet to recognize, never mind address. All of that comes into play in the interview encounter, and it may determine whether the interview happens at all. A humility before this pageant of exclusion is the necessary companion to empathy.

What I’m presenting here isn’t new. The oral history community has been wrestling with these questions for a long time, especially with its frequently expressed commitment to using oral history to explore those hierarchies of value, to shine a light on and validate the experiences of the excluded and the othered. Although I’m an oral historian, I’m also a historian of science. One of the things I’m interested in is how disciplines define themselves. One of the patterns about knowers in a discipline is that they are sometimes poor interpreters of their own origins and practices. Researchers often have the hardest time seeing the very spot from which they observe. It may be precisely because of their commitment to reflexivity that oral historians may not be able to see, or perhaps hear, these challenges. We check our audio equipment, but sometimes we don’t check how we are listening, or whether we’re able to hear something at all. Our most important listening equipment is between our ears, or maybe inside our chests, and limited by our lived experience and frames of reference. What we need to continually re-examine and affirm is our commitment to empathy, humility, and trust in our work.

A Good Talk with Shanna Farrell

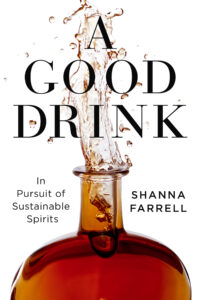

A couple of weeks ago, I had the opportunity to “sit down” remotely with my colleague Shanna Farrell to talk about her new book A Good Drink: In Pursuit of Sustainable Spirits, out last month with Island Press. I wanted to ask her about her book in light of her experience and perspectives as an oral historian.

A couple of weeks ago, I had the opportunity to “sit down” remotely with my colleague Shanna Farrell to talk about her new book A Good Drink: In Pursuit of Sustainable Spirits, out last month with Island Press. I wanted to ask her about her book in light of her experience and perspectives as an oral historian.

Burnett: Throughout the book, you are careful to situate yourself in terms of race, gender, and nationality, and you identify and explore the racially exploitative history of spirits production. How did you approach race and inclusion as criteria in your interviewing?

Farrell: Race and inequality is a very important aspect of the beverage industry and a topic that isn’t always highlighted in a story. I felt that it was necessary to acknowledge the exploitative history of a few spirits in the book, especially when it comes to the link of slavery and colonialism. The book tells the story of the people who make, or made, each spirit, and this includes enslaved people. The spirits industry wouldn’t exist without them and it is crucial that their contributions be recognized, as well as the systems of power, such as colonialism, that impact their place on the global stage. I also wanted to acknowledge that I’m not always the best person to tell specific aspects of these stories, like the chapter on agave. As an oral historian, I ask people to narrate and make meaning of their own lives, and wanted someone from Mexico to tell the story of mezcal. I’m grateful to those who were willing to share their stories.

Burnett: Could you tell us about influences on this book project, and how you thought about distinguishing your own voice as a writer?

Farrell: Though I write non-fiction, I read a lot of fiction. Narrative, structure, and imagery are all big parts of how I think about literature, my work as an oral historian, and as a writer. Topics related to sustainability can sometimes feel heady or overly scientific, so I wanted to make the book approachable for readers so they could connect to environmental issues. I channeled my favorite fiction and poetry prose when I was writing with the hope that the audience would find it engaging.

Burnett: Trust is such an important factor in oral history work. Tell us about how you built trust among the various communities you worked with for this book. What were some of the challenges to be overcome?

Farrell: Trust is crucial. Like in oral history, my work with the narrators in A Good Drink were built on relationships. I’d been bartending for over a decade when I was making these connections and I relied on the cocktail community to introduce me to narrators. I used a lot of oral history methods when I was getting to know these folks, like being transparent about what I was doing (writing a book), asking for consent to record them, and allowing them to review the section of drafts that they were in. These methods were paramount in gaining trust and I’m still in touch with many of the people in the book.

Burnett: In oral history, we’re used to helping narrators make meaning out of their stories. Can you tell us about how you balanced that approach with your role as sole author?

Farrell: I was interviewing people about their approach to sustainability when making spirits or mixing drinks and we’d often discuss the implications of their various models on the environmental, like carbon footprints and climate change. While my interviews for this book were not so much life histories–wherein narrators are asked to reflect back on their lives and make meaning of them more explicitly–the people featured in my book had the opportunity to see where their work fit into the big picture. From there, I shaped the narrative to illustrate a spectrum of ways that eco-consciousness extends from the farm to the distillery, instead of a “one size fits all” approach.

Burnett: Did your interviewing process change as you moved through the project? Did the interviews become more focused, for example?

Farrell: I used oral history interviewing techniques with most of the interviews I did for the book. In many cases, we started at the beginning of someone’s life or work to understand how they became interested in the environment and when they realized it was possible to incorporate sustainable practice into making spirits. Some of the interviews, especially the ones that I did during the COVID-19 pandemic, were remote, so we took more of a topical approach because of the interview format. I asked both specific and broad questions in each of the interviews, and many follow-up questions. I also did quite a bit of field work, which included distillery and farm visits, so these experiences were blended into the interview process.

Burnett: When you began your project, you had a pretty clear idea of the themes you wanted to explore, such as sustainability. What were some themes that emerged from the interviews themselves, and how did you incorporate them? Did some topics or themes emerge that didn’t quite fit this project that you might want to work on in the future?

Farrell: Sustainability was the organizing theme from the very start of this project. But each category of spirit has a different set of circumstances because the source material–the raw ingredients, like corn, agave, sugarcane, and pears–all grow differently. It’s possible to practice crop rotation for some of these crops (like corn) but not for others (pears), so I learned that there are complex challenges for each corner of the market. We can’t judge all spirits the same way, especially when it comes to sustainability.

Burnett: You write that the project began with your realization that there was an unsung world of distillers who thought about spirits as slow food. What’s great about your interviewing is that you really get inside what slow food, organic, community farming, and farm-to-table practices mean to people who do this work. My impression is that storytelling seems to be inseparable from the products your narrators produce: “Know what you are drinking;” “We’re talking about how a bottle tells a story.” Put another way, part of the value of the product is the story of making it, the cultures that surround it. To the extent that that’s true, did you adapt your interviewing style and your own storytelling to this context?

Farrell: You’re right–the story of how these spirits are made is an integral part of their identity and what gives a distiller a unique voice in a crowded market. I was aware of this going into the interviews, so I didn’t change my style of interviewing very much. Instead, I spent a lot of time talking to people about farming practices and how to capture the essence of the ingredients in a bottle, which isn’t something you hear much about when people talk about spirits. I was less interested in how spirits are aged or what type of wood they rested in–aspects that dominate most of these conversations–and focused on the origin story of each of the products. I found that the people who were really thinking about how their spirits are agricultural products and how they fit into the food system had a lot of say about this, so I knew I was hitting on an important topic.

Burnett: On the producer side, this is a story of small, innovative entrepreneurs lifting up local work and community and environmental values. But on the consumer side, these often involve quite expensive products and practices. Given your last chapter on the prospect of scaling up these small, artisanal practices, are you optimistic about greater accessibility down the road on the consumer side?

Farrell: I’m very optimistic that these products will be more accessible down the line, not just in terms of price but in where they are available. In the book, I focused on one of the spirits in their line, but many of the narrators have many more products that sell for various prices. It’s not cheap to make high quality products so I don’t think a bottle of Jimmy Red will ever cost $15–and it shouldn’t–but they have other products that aren’t as pricey. And while many of these producers are distributed nationally, some aren’t; I’m hopeful that someday soon they’ll be more widely available so we can all try just how delicious a sustainable spirit can be.

A Good Drink is available at your local independent bookstore.