Tag: Philanthropy

Helping Hands: A Guide to the Oral History Center’s Advocacy and Philanthropy Individual Interviews

By Lauren Sheehan-Clark

The Oral History Center’s Advocacy and Philanthropy project tells the history of our world from the perspective of those who went above and beyond to help shape it. From local Bay Area volunteers to international activists, these interviews serve as a guide through history, highlighting some of the prominent social concerns and reform movements of the last century.

For a look into the Progressive Era of the early twentieth century, you can read interviews from UC Berkeley alumni Adeline Toye Cox and Emma McCaughlin, who focused their volunteer efforts on fledgling organizations such as Planned Parenthood and the League of Women Voters. Or, if you’re interested in the 1940s and 1950s, several of the interviewees in this project discuss their involvement with postwar activism, including Edith Simon Coliver, who served as an interpreter during the Nuremberg trials, and Florette Pomeroy, who worked with the United Nations to repatriate lost children.

The project only continues to grow from there, with countless interviews on the social concerns of the latter half of the twentieth century. Carol Rhodes Sibly, a Berkeley community leader, touches on the movement to integrate schools in the East Bay, while Sally Lilienthal recounts her long-term commitment to preventing the proliferation of nuclear weapons through her organization, the Ploughshares Fund.

If that’s not enough, take a look at some of the highlights from this rich collection of interviews.

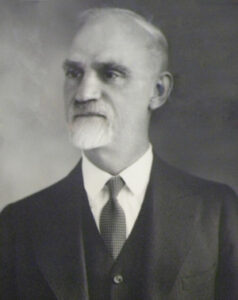

Newel Perry: The California Council for the Blind

Newel Perry was a leading figure in disability activism in the early twentieth century, establishing the influential California Council of the Blind in 1934. Blind himself from the age of eight, Dr. Perry advocated for the self-sufficiency of individuals who were blind and visually impaired, and sought to increase their economic opportunities, particularly for students who wished to attend university. Throughout the mid-twentieth century, the Council was credited for a wealth of progressive legislation for Californians with disabilities, in addition to inspiring the larger National Federation of the Blind, established in 1940.

Elinor Heller: A Volunteer in Politics, in Higher Education, and on Governing Boards

Hailing from San Francisco, Elinor Heller was a former committeewoman for California in the Democratic National Committee (1948–1952) and chairwoman of the University of California Board of Regents. In her work with the Committee, she witnessed the appointment of Harry Truman as vice president and his eventual rise to the presidency, while her time with the Regents overlapped with the influential free speech movement led by Berkeley students. In addition to her volunteer work with the League of Women Voters and other organizations, this interview covers Heller’s thoughts on major political campaigns of the mid-century and university-student relationships.

Isabel Wong-Vargas: Commerce, Industry, and Labor, Family & Personal Philanthropy in Peru, China and the United States

A jack of all trades, Isabel Wong-Vargas was an entrepreneur, restaurant developer, and philanthropist who founded the highly successful restaurant, La Caleta, in Peru. Wong-Vargas spent much of her life in China and Peru before settling in the Bay Area in 1966, where she was named San Francisco’s honorary consul for Peru. In this expansive interview, Wong-Vargas discusses her memories of World War II and the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, gender roles and divorce in pre-revolution China, Peruvian business practices, and her later years in the Bay Area.

Midge Wilson: An Oral History

Midge Wilson was an activist and community leader who founded the Bay Area Women’s and Children’s Center in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco in the 1980s. A longtime resident of the Tenderloin, Wilson’s dedication to the community was extensive: She helped to establish clothing drives, youth programs, and recreation centers, as well as the neighborhood’s first public school, the Tenderloin Community School. In this interview, Wilson discusses her extensive work with the Bay Area Women’s and Children’s Center, fundraising strategies, youth programs and education, and changes to the Tenderloin community in the 1980s and beyond.

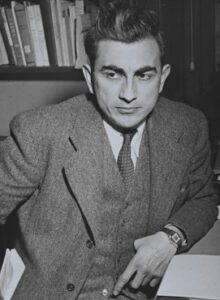

Ernesto Galarza: The Burning Light

Another household name, Ernesto Galarza was an influential labor organizer whose activism in the late 1940s laid the groundwork for the Chicano movement of the 1960s. Born in Jalcocotán, Mexico and immigrating to the United States at a young age, he began organizing strikes against the DiGiorgio Corporation in 1948 and worked closely with the American Federation of Labor’s National Agricultural Workers Union. In this collection of speeches and discussions, Galarza discusses data-driven methods of community activism, as well as his years as a professor and the challenges of bilingual education.

Find these and all the Oral History Center’s interviews from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Find projects, including the Advocacy and Philanthropy —Individual Interviews project, through the Projects tab on our home page.

All in all, the narrators in our Advocacy and Philanthropy project had a profound impact on the communities around them, whether big or small, local or global. So if you’re looking for a bit of advice or mentorship from celebrated leaders, look no further: Get reading, and get inspired.

Lauren Sheehan-Clark, a recent graduate of UC Berkeley, studied history and English, and was an editorial assistant at the Oral History Center.

Further Reading and Resources from The Bancroft Library

Blind Educator: The Story of Newel Lewis Perry, by Thomas Buckingham. BANC; xF860.P42.B8

Farm Workers and Agri-business in California, by Ernesto Galarza. Bancroft ; F862.2G14

Interviews on the University of California loyalty oath controversy. Bancroft ; Phonotape 3799 C:1-9. Interviews conducted for David P. Gardner’s thesis, The University of California loyalty oath controversy.

See also “I take this obligation freely:” Recalling UC Berkeley’s loyalty oath controversy, by Shannon White with research by Adam Hagen.

Newel Perry papers. BANC MSS 67/33 c. Presidential campaign, 1940. Democratic Party. Bancroft Folio ; f JK2256 1940d. Party platform, printed copies of speeches, pamphlets, broadsides, clippings and dodgers used in the 1940 presidential campaign of the Democratic Party.

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

New Project Release: Marion and Herb Sandler Oral History Project

New Project Release: Marion and Herb Sandler Oral History Project

Herb Sandler and Marion Osher Sandler formed one of the most remarkable partnerships in the histories of American business and philanthropy—and, if their friends and associates would have a say in things, in the living memory of marriage writ large. This oral history project documents the lives of Herb and Marion Sandler through their shared pursuits in raising a family, serving as co-CEOs for the savings and loan Golden West Financial, and establishing a remarkably influential philanthropy in the Sandler Foundation. This project consists of eighteen unique oral history interviews, at the center of which is a 24-hour life history interview with Herb Sandler.

Marion Osher Sandler was born October 17, 1930, in Biddeford, Maine, to Samuel and Leah Osher. She was the youngest of five children; all of her siblings were brothers and all went on to distinguished careers in medicine and business. She attended Wellesley as an undergraduate where she was elected into Phi Beta Kappa. Her first postgraduate job was as an assistant buyer with Bloomingdale’s in Manhattan, but she left in pursuit of more lofty goals. She took a job on Wall Street, in the process becoming only the second woman on Wall Street to hold a non-clerical position. She started with Dominick & Dominick in its executive training program and then moved to Oppenheimer and Company where she worked as a highly respected analyst. While building an impressive career on Wall Street, she earned her MBA at New York University.

Herb Sandler was born on November 16, 1931 in New York City. He was the second of two children and remained very close to his brother, Leonard, throughout his life. He grew up in subsidized housing in Manhattan’s Lower East Side neighborhood of Two Bridges. Both his father and brother were attorneys (and both were judges too), so after graduating from City College, he went for his law degree at Columbia. He practiced law both in private practice and for the Waterfront Commission of New York Harbor where he worked on organized crime cases. While still living with his parents at Knickerbocker Village, he engaged in community development work with the local settlement house network, Two Bridges Neighborhood Council. At Two Bridges he was exposed to the work of Episcopal Bishop Bill Wendt, who inspired his burgeoning commitment to social justice.

Given their long and successful careers in business, philanthropy, and marriage, Herb and Marion’s story of how they met has taken on somewhat mythic proportions. Many people interviewed for this project tell the story. Even if the facts don’t all align in these stories, one central feature is shared by all: Marion was a force of nature, self-confident, smart, and, in Herb’s words, “sweet, without pretentions.” Herb, however, always thought of himself as unremarkable, just one of the guys. So when he first met Marion, he wasn’t prepared for this special woman to be actually interested in dating him. The courtship happened reasonably quickly despite some personal issues that needed to be addressed (which Herb discusses in his interview) and introducing one another to their respective families (but, as Herb notes, not to seek approval!).

Within a few years of marriage, Marion was bumping up against the glass ceiling on Wall Street, recognizing that she would not be making partner status any time soon. While working as an analyst, however, she learned that great opportunity for profit existed in the savings and loan sector, which was filled with bloat and inefficiency as well as lack of financial sophistication and incompetence among the executives. They decided to find an investment opportunity in California and, with the help of Marion’s brothers (especially Barney Osher), purchased a tiny two-branch thrift in Oakland, California: Golden West Savings and Loan.

Golden West—which later operated under the retail brand of World Savings—grew by leaps and bounds, in part through acquisition of many regional thrifts and in part through astute research leading to organic expansion into new geographic areas. The remarkable history of Golden West is revealed in great detail in many of the interviews in this project, but most particularly in the interviews with Herb Sandler, Steve Daetz, Russ Kettell, and Mike Roster, all of whom worked at the institution. The savings and loan was marked by key attributes during the forty-three years in which it was run by the Sandlers. Perhaps most important among these is the fact that over that period of time the company was profitable all but two years. This is even more remarkable when considering just how volatile banking was in that era, for there were liquidity crises, deregulation schemes, skyrocketing interest rates, financial recessions, housing recessions, and the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s, in which the entire sector was nearly obliterated through risky or foolish decisions made by Congress, regulators, and managements. Through all of this, however, Golden West delivered consistent returns to their investors. Indeed, the average annual growth in earnings per share over 40 years was 19 percent, a figure that made Golden West second only to Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, and the second best record in American corporate history.

Golden West is also remembered for making loans to communities that had been subject to racially and economically restrictive redlining practices. Thus, the Sandlers played a role in opening up the dream of home ownership to more Americans. In the offices too, Herb and Marion made a point of opening positions to women, such as branch manager and loan officer, previously held only by men. And, by the mid-1990s, Golden West began appointing more women and people of color to its board of directors, which already was presided over by Marion Sandler, one of the longest-serving female CEOs of a major company in American history. The Sandlers sold Golden West to Wachovia in 2006. The interviews tell the story of the sale, but at least one major reason for the decision was the fact that the Sandlers were spending a greater percentage of their time in philanthropic work.

One of the first real forays by the Sandlers into philanthropic work came in the wake of the passing of Herb’s brother Leonard in 1988. Herb recalls his brother with great respect and fondness and the historical record shows him to be a just and principled attorney and jurist. Leonard was dedicated to human rights, so after his passing, the Sandlers created a fellowship in his honor at Human Rights Watch. After this, the Sandlers giving grew rapidly in their areas of greatest interest: human rights, civil rights, and medical research. They stepped up to become major donors to Human Rights Watch and, after the arrival of Anthony Romero in 2001, to the American Civil Liberties Union.

The Sandlers’ sponsorship of medical research demonstrates their unique, creative, entrepreneurial, and sometimes controversial approach to philanthropic work. With the American Asthma Foundation, which they founded, the goal was to disrupt existing research patterns and to interest scientists beyond the narrow confines of pulmonology to investigate the disease and to produce new basic research about it. Check out the interview with Bill Seaman for more on this initiative. The Program for Breakthrough Biomedical Research at the University of California, San Francisco likewise seeks out highly-qualified researchers who are willing to engage in high-risk research projects. The interview with program director Keith Yamamoto highlights the impacts and the future promise of the research supported by the Sandlers. The Sandler Fellows program at UCSF selects recent graduate school graduates of unusual promise and provides them with a great deal of independence to pursue their own research agenda, rather than serve as assistants in established labs. Joe DeRisi was one of the first Sandler Fellows and, in his interview, he describes the remarkable work he has accomplished while at UCSF as a fellow and, now, as faculty member who heads his own esteemed lab.

The list of projects, programs, and agencies either supported or started by the Sandlers runs too long to list here, but at least two are worth mentioning for these endeavors have produced impacts wide and far: the Center for American Progress and ProPublica. The Center for American Progress had its origins in Herb Sandler’s recognition that there was a need for a liberal policy think tank that could compete in the marketplace of ideas with groups such as the conservative Heritage Foundation and the American Enterprise Institute. The Sandlers researched existing groups and met with many well-connected and highly capable individuals until they forged a partnership with John Podesta, who had served as chief of staff under President Bill Clinton. The Center for American Progress has since grown by leaps and bounds and is now recognized for being just what it set out to be.

The same is also true with ProPublica. The Sandlers had noticed the decline of traditional print journalism in the wake of the internet and lamented what this meant for the state of investigative journalism, which typically requires a meaningful investment of time and money. After spending much time doing due diligence—another Sandler hallmark—and meeting with key players, including Paul Steiger of the Wall Street Journal, they took the leap and established a not-for-profit investigative journalism outfit, which they named ProPublica. ProPublica not only has won several Pulitzer Prizes, it has played a critical role in supporting our democratic institutions by holding leaders accountable to the public. Moreover, the Sandler Foundation is now a minority sponsor of the work of ProPublica, meaning that others have recognized the value of this organization and stepped forward to ensure its continued success. Herb Sandler’s interview as well as several other interviews describe many of the other initiatives created and/or supported by the foundation, including: the Center for Responsible Lending, Oceana, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Learning Policy Institute, and more.

Herb and Marion Sandler also played key roles in the formation and funding of two important research centers here on the UC Berkeley campus which have a global reach: the Berkeley Center for Equitable Growth (CEG) and the Human Rights Center. The CEG is directed by economist Emmanual Saez and has supported the influential work of Thomas Piketty which looks at methods for reducing wealth and income disparities around the globe. The Human Rights Center has for the past 25 years investigated and shed light upon human rights abuses around the globe.

A few interviewees shared the idea that when it comes to Herb and Marion Sandler there are actually three people involved: Marion Sandler, Herb Sandler, and “Herb and Marion.” The later creation is a kind of mind-meld between the two which was capable of expressing opinions, making decisions, and forging a united front in the ambitious projects that they accomplished. I think this makes great sense because I find it difficult to fathom that two individuals alone could do what they did. Because Marion Sandler passed away in 2012, I was not able to interview her, but I am confident in my belief that a very large part of her survives in Herb’s love of “Herb and Marion,” which he summons when it is time to make important decisions. And let us not forget that in the midst of all of this work they raised two accomplished children, each of whom make important contributions to the foundation and beyond. Moreover, the Sandlers have developed many meaningful friendships (see the interviews with Tom Laqueur and Ronnie Caplane), some of which have spanned the decades.

The eighteen interviews of the Herb and Marion Sandler oral history project, then, are several projects in one. It is a personal, life history of a remarkable woman and her mate and life partner; it is a substantive history of banking and of the fate of the savings and loan institution in the United States; and it is an examination of the current world of high-stakes philanthropy in our country at a time when the desire to do good has never been more needed and the importance of doing that job skillfully never more necessary.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director, Oral History Center, UC Berkeley

List of Interviews of the Marion and Herbert Sandler Oral History Project

Ronnie Caplane, “Ronnie Caplane: On Friendship with Marion and Herb.”

Joseph DeRisi, “Joe DeRisi: From Sandler Fellow to UCSF Professor of Biochemistry.”

Stephen Hauser, “Stephen Hauser: Establishing the Sandler Neurosciences Center at UCSF.”

Russell Kettell, “Russ Kettell: A Career with Golden West Financial.”

Thomas Laqueur, “Tom Laqueur: On the Meaning of Friendship.”

Bernard Osher, “Barney Osher: On Marion Osher Sandler.”

Michael Roster, “Michael Roster: Attorney and Golden West Financial General Counsel.”

Kenneth Roth, “Kenneth Roth: Human Rights Watch and Achieving Global Impact.”

Herbert Sandler, “Herbert Sandler: A Life with Marion Osher Sandler in Business and Philanthropy.”

James Sandler, “Jim Sandler: Commitment to the Environment in the Sandler Foundation.”

Susan Sandler, “Susan Sandler: The Sandler Family and Philanthropy.”

William Seaman, “Bill Seaman: The American Asthma Foundation.”

Paul Steiger, “Paul Steiger: Business Reporting and the Creation of ProPublica.”

Richard Tofel, “Richard Tofel: The Creation and Expansion of ProPublica.”

OHC Director’s Column – January 2019

From the Oral History Center Director:

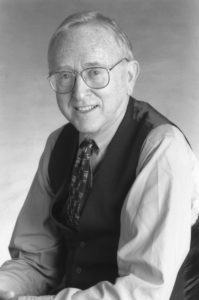

Paul “Pete” Bancroft, III, a 1951 graduate of Yale, a pioneer in venture capital, and the eldest great-grandson of Bancroft Library founder Hubert Howe Bancroft, died peacefully in his sleep on January 3, 2019, at the age of 88.

We at The Bancroft Library’s Oral History Center are extremely grateful for his support of over the years. The word “support,” however, is wholly inadequate to capture what he did for oral history at Berkeley. Pete Bancroft was, in fact, its greatest single benefactor in the 65-year history of our office.

Pete’s first major engagement with the Oral History Center (or, as we were known at the time, the Regional Oral History Office) began around 2007 with discussions about a possible oral history project documenting the history of venture capital in the Bay Area. Not only did Pete step forward to sponsor the project, he played a critical role in helping to articulate the major themes and issues to be covered in the interviews. He also created an advisory committee of scholars and leaders in the field that gave the project instant credibility and served on that committee; and he reached out personally to many of the key players whom we wished to interview, setting forth the goals of the project and convincing those who might have been reluctant to participate. Sally Hughes, who was the project director and interviewer for these oral histories, wrote to me upon learning of Pete’s death: “As the interviewer for the Center’s venture capital project, I could not have asked for a better sponsor in organizing, completely funding, and advising the project every step of the way. In his warm and supportive manner, he made it clear that we were a partnership in trying to create the best possible series of interviews on the foundational era of venture capital. It was a subject dear to his heart as one of its early participants.” When completed, the project resulted in 19 lengthy oral history interviews with the pioneers of venture capital, including Franklin “Pitch” Johnson, Art Rock, Reid Dennis, Tom Perkins, Don Lucas, Don Valentine, Bill Draper, Bill Bowes, and Pete himself. In addition, Pete facilitated the donation of another group of interviews already conducted by the National Venture Capital Association. Pete Bancroft played a crucial role in creating this “must read” resource for anyone interested in the history of venture capital.

The years around the financial crisis of 2008 were difficult ones for this office. In addition to waning donations and external support, several retirements left us greatly understaffed. For the few of us remaining, myself included, there was a nervously voiced worry that the fifty-plus year tradition of oral history at Berkeley might be reaching an end. In the wake of these worries, Pete was conspiring behind the scenes to make certain that oral history would continue at Berkeley. He was a good friend of long-time Bancroft Library director Charles Faulhaber. When Faulhaber retired in 2011, Pete paid tribute to his friend’s leadership of Bancroft by creating the Charles B. Faulhaber Endowment, whose income was to be dedicated to the oral history program. Pete had only one request: that the name of the office be changed. Happily, the staff of the center recognized that we had long ago outgrown the “regional” in our former name and readily embraced the new moniker of the “Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library.”

Other than the name change, Pete asked for nothing in return for creating the Faulhaber endowment, which was built with his donations and those of many of his friends and venture capital colleagues. This endowment has been critical to the recent success of this office. Because only one of eight full-time staff positions, and none of the related costs of conducting interviews (equipment, transcription, travel), is paid for by the university, all of our projects require external funding. However, project funds can only support project-related activities and there is a lot more that we do — and want to do — than just conducting interviews, transcribing them, and editing them. Pete Bancroft’s “Charles Faulhaber Endowment” allows the Oral History Center to do so much more: we can host formal and informal training for those who want to learn oral history methodology from our highly-skilled team of historians; we can now create interpretative materials based on the interviews that we conduct, including, now, three seasons of our in-depth podcast series, “The Berkeley Remix”; and, perhaps most importantly, the Faulhaber endowment allows us to conduct research and development in support of new projects. We are fortunate to have a smart, ambitious, and creative group of oral historians who come up with potentially important project ideas; this endowment gives us the ability to pursue those ideas by doing background research, conducting pilot interviews, and seeking funding to make these ideas a reality. Thus, Pete Bancroft continued his career in venture capital with the Oral History Center: by providing perpetual seed funding, he has established a lasting legacy of innovation, experimentation, and entrepreneurship among the publicly-engaged scholars at the center!

In his final months of life, Pete Bancroft continued to think about and look after his friends, including the Oral History Center. Charles Faulhaber, returning the honor given to him by Pete, created the “Pete Bancroft Endowment for the Oral History Center,” with an initial gift from Pitch Johnson and additional gifts from many of the same philanthropists who supported the earlier one as well as his ‘Hill Billies’ campmates at the Bohemian Club. And like the Faulhaber endowment, this one will support the ongoing work on the Oral History Center. In a touching note just after Pete’s passing, Faulhaber let me know that Pete was thinking of us until the end, making a major donation to the endowment in the final weeks of his life. With this news, we sadly bid farewell to an esteemed and gracious benefactor — our angel investor.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director of the Oral History Center

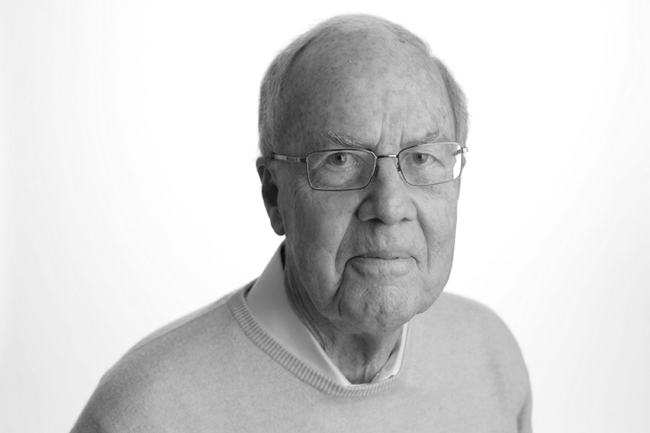

In Memory of William K. Bowes, Jr.

William K. Bowes, Jr. died peacefully at home on December 28, 2016 after a long illness. A leading member of the first generation of venture capitalists, he was a private investor in many of the earliest startups in what became known as Silicon Valley. In 1981, he founded U.S. Venture Partners where his conviction that venture capitalists should actively guide companies rather than simply invest in them was a basic principle. His focus was the biomedical industry, an interest he inherited from his physician father. The investment of which he was most proud was in Amgen, a pioneering biotechnology company of which he was founding shareholder and the startup’s first chairman and treasurer. Not a man of many words, he was known for his brief, to-the- point interjections in business negotiations. In later years, Bowes’s interest turned to philanthropy in the fields of science, the arts, education, and the environment. Among his many generous bequests was a recent pledge of $50 million to the University of California, San Francisco to support young investigators. A far cry from the hard-driving venture capitalist, Bowes was known for his self-effacing manner and personal warmth. For details of his life and contributions, read his oral history transcript.