Tag: undergraduate research

The Bancroft Library offers fellowships to support research in our special collections

We invite graduate students, undergraduates, and independent scholars to apply by Feb. 5, 2024

The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley is pleased to announce we are now accepting applications for our 2024-25 fellowships and awards, available to graduate students, undergraduates, and independent scholars conducting research in our special collections. The Bancroft Library is committed to fostering a diverse and inclusive research environment, and seeks to support students and scholars using the collections both for traditional archival and bibliographic research, as well as those wishing to use the collections for creative projects.

Applications are due February 5, 2024, at 5 p.m., with decisions to be made by early April 2024.

Research areas

Several fellowships offer funding for research that would benefit from the use of any source materials in The Bancroft Library. Other fellowships are focused around specific subject areas. Our fellowships and awards range in amounts.

Our 2024-25 fellowships and awards are in the following research areas:

- Research that would benefit from the use of any source materials in the Bancroft

- History of California

- Nineteenth century American West and related topics

- Jewish experience in California from 1848 to 1915

- Print culture in any part of the Western Hemisphere, or any investigation of the history of the book in the Americas

How to apply

Our Fellowships and Awards website has details about all the eligibility criteria for each fellowship or award, and the application process. Some opportunities are designated for Berkeley undergraduates, some for graduate students at any University of California campus, and some are open to students at any college or university or independent scholars —complete descriptions are on the website.

Please share this announcement with undergraduate and graduate students, and anyone else who may be interested in The Bancroft Library’s fellowship program.

About the Bancroft Library

The Bancroft Library is the primary special collections library at UC Berkeley, and one of the largest and most heavily used libraries of manuscripts, rare books, and unique materials in the United States. Bancroft supports major research and instructional activities and plays a leading role in the development of the university’s research collections.

Since Bancroft is a reference library, its collections are non-circulating, which means they are only available for your use in the Heller Reading Room. Fellowships and Awards facilitate this in-person research.

The Bancroft Library welcomes researchers from the UC Berkeley campus, nationally, and from around the world. Our holdings currently include: more than 600,000 volumes; 60 million manuscript items; 8 million photographs/pictorial materials; over 3 million digital files; 43,000 microforms; and 23,000 maps.

People worldwide can access Bancroft’s digital collections, which include digitized materials from the library’s extensive and ever-growing holdings, as well as born digital materials collected as part of our archival manuscript and pictorial collections.

Lucy Sprague Mitchell: Child Education Reformer and Berkeley’s First Dean of Women

By Deborah Qu

“It was naive, but it wasn’t as naive as it sounds.” — Lucy Sprague Mitchell on chasing her dream to expand career prospects for women

One hundred and fifty years ago in 1870, the UC Regents first declared that the university’s doors were open to women students, giving them the opportunity to pursue a higher education. Access to student facilities, housing, and resources were still far from equal for women. Thus began an era where thousands of young women pioneered for positive change, making their mark on the university, as well as transforming society at large. One of these women was Lucy Sprague Mitchell, the first dean of women from 1906–1912, and one of the first women instructors in UC Berkeley’s Department of English. Mitchell, an advocate for educational reform, had observed that “public opinion reacts very slowly. And there’s always been something that irritates me, and that is the voices against are so much louder than the voices for.” Yet her unrelenting optimism and her passion for education allowed her to introduce a more holistic framework for child learning and expand career prospects for women outside the limited field of teaching.

Born in 1878, Lucy Sprague Mitchell grew up in a traditional household where any sort of play was seen as “a waste of time.” In a 1962 interview with the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library, Mitchell recalls a multitude of happy childhood memories, but they were also mixed with conflicting feelings of unworthiness and loneliness caused by her family’s strict Puritan modes of discipline. It is possible that these childhood learning experiences were great influencers in her later experimental work in education. In her autobiography, Two Lives: The Story of Wesley Clair Mitchell and Myself, she explained how she believed that the entire learning process is not complete without the “intake” of experience transforming into an “outgo,” or some living, creative action caused from the development. Perhaps these mixed childhood memories had also inspired her to take positive action through childhood education reform.

After graduating from Radcliffe College, Lucy Sprague Mitchell was appointed as Berkeley’s first dean of women at only age 23. In her oral history, Mitchell recalled a conversation she had with the university President Benjamin Ide Wheeler. His instructions were “to find out what needs to be done and to do it.” While terrified and confused, this is exactly what Mitchell did. As dean of women, Mitchell did not succumb to the “motherly” role to students that was expected of her in the early 1900s. Instead her youthful perspective allowed her to expand beyond the traditional housing and counseling needs to truly connect with students at Cal. She initiated community trips, poetry readings, and sex education discussions. She organized Parthenia, which she fondly called greek for “women of the Parthenon,” a performative showcase about various historical women and imagined female characters.

In her oral history, Mitchell reflected on why she wanted to leave her role as dean of women; Mitchell explained that her interests truly were rooted in education, not administration. During her years working with women students, she had become, she says, “extremely concerned about the lack of professional training for women excepting in the field of teaching. She explained how “not everybody is equipped to be a teacher, nor wants to be a teacher.” At the time, Mitchell found it jarring that over 90 percent of the women students she surveyed had planned to become a teacher after graduation. While Cal was progressive for its time, teaching was the most socially acceptable profession and “the only thing that the University offered to women.” In retrospect, Lucy Sprague Mitchell believed that her real reason for requesting a leave from Berkeley “was to try to explore different fields of work that women could enter and for which the University could train them.”

This disaffection inspired innovation. Lucy Sprague Mitchell brought the issue of limited education for women to six social organizations in New York, completing statistical fieldwork from women working in nursing, to labor legislation about city tenements, to public schools. Her exposure to public school education had such a profound effect on Mitchell that she became an educator resource for teachers throughout 1922–1955. She began developing experimental methods about childhood education and classroom procedure that promoted creative expression and holistically fulfilled a child’s emotional, physical, and mental needs. Her emphasis on “relationship teaching” and “active learning” over memorization helped shape the way for “social studies,” a course widely studied in American classrooms today. Her focus on the learning environment was unorthodox at the time, and it led her to new paradigms of using childhood maturity instead of age to measure emotional intellectual development. She founded Bank Street College of Education in New York as a graduate student teacher training institution in 1916 based on this same philosophy.

From my perspective as an undergraduate student at Cal, Lucy Sprague Mitchell’s life story teaches me that to truly orchestrate change, we should not just be focusing on the various problems of the present, but rather dreaming about all the future potential. The oral history interview allowed Lucy Sprague Mitchell to recount the early dream she had formed working with Cal students in her late 20s: to provide opportunities for young women to pursue rich and nuanced fields of study. This dream certainly did not go to waste. As a young college woman with a wide selection of majors to choose from, I am grateful that she and many others helped pave the way. Reflecting on this vision for women, Lucy Sprague Mitchell said, “Now that sounds very naive. It was naive, but it wasn’t as naive as it sounds.”

Deborah Qu is a first year undergraduate student who intends to study psychology. As a part of the celebration of 150 years of women at Berkeley, Deborah is researching the Oral History Center’s vast archive to identify women in the collection with a relationship to UC Berkeley.

Find this and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

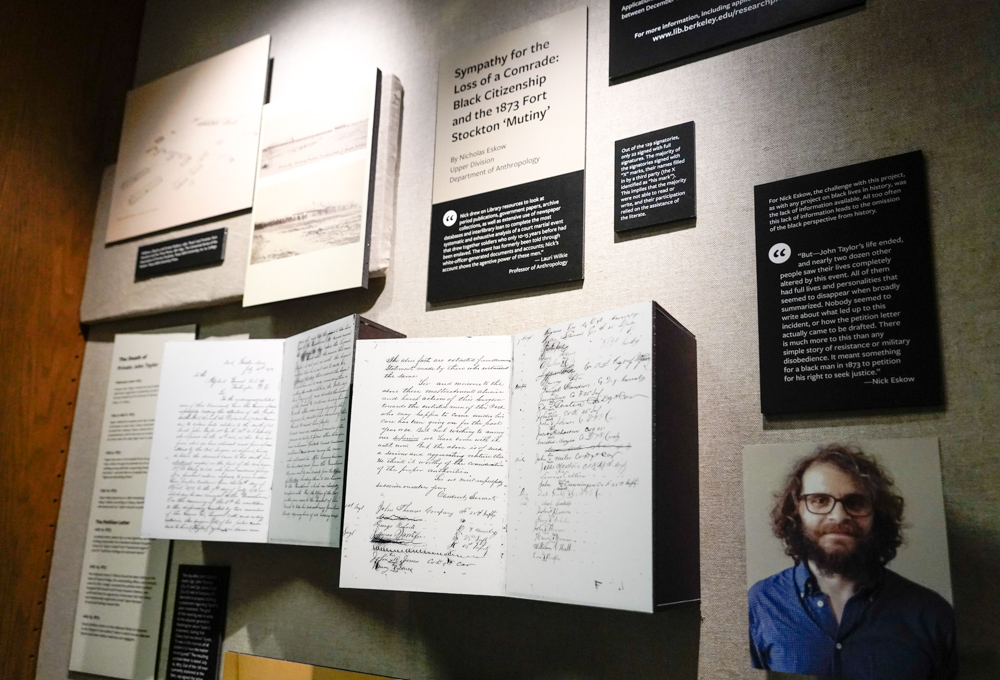

Library Prize Exhibit: Sympathy for the Loss of a Comrade

By Adam Clemons

In early July of 1873, a soldier named John Taylor reported to the hospital at Fort Stockton, Texas complaining of illness. The fort’s doctor, Peter J.A. Cleary, refused to treat him. Instead, he sent Taylor to the guard house as punishment. Three days later John Taylor was dead. Taylor’s fellow soldiers, incensed by what they believed to be racially motivated medical neglect by Cleary, drafted a statement detailing the patterns of abusive treatment of Taylor and calling for a formal investigation into his death. The officers at Fort Stockton responded by placing twenty-one of the soldiers who signed the letter, mostly non-commissioned officers, on trial for attempted mutiny. Though the charge was ultimately downgraded to a failure to follow proper procedure, twenty out of the twenty-one charged soldiers were dishonorably discharged and sent to prison in Huntsville, Texas.

Photos by Jami Smith for the UC Berkeley Library

In “Sympathy for the Loss of a Comrade: Black Citizenship and the 1873 Fort Stockton ‘Mutiny’,” Nick Eskow successfully reconstructed the events at Fort Stockton using library resources such as period publications, government documents, newspapers, and archival collections. Where others have relied on the accounts of the white officers to tell this story, Eskow sought out the perspective of the black soldiers through extensive research and analysis of the historical record. Eskow’s exceptional effort earned him the prestigious 2018 Charlene Conrad Liebau Library Prize for Undergraduate Research, an annual prize awarded to students who have done high-level, course-based research while demonstrating significant use of the Library’s resources.

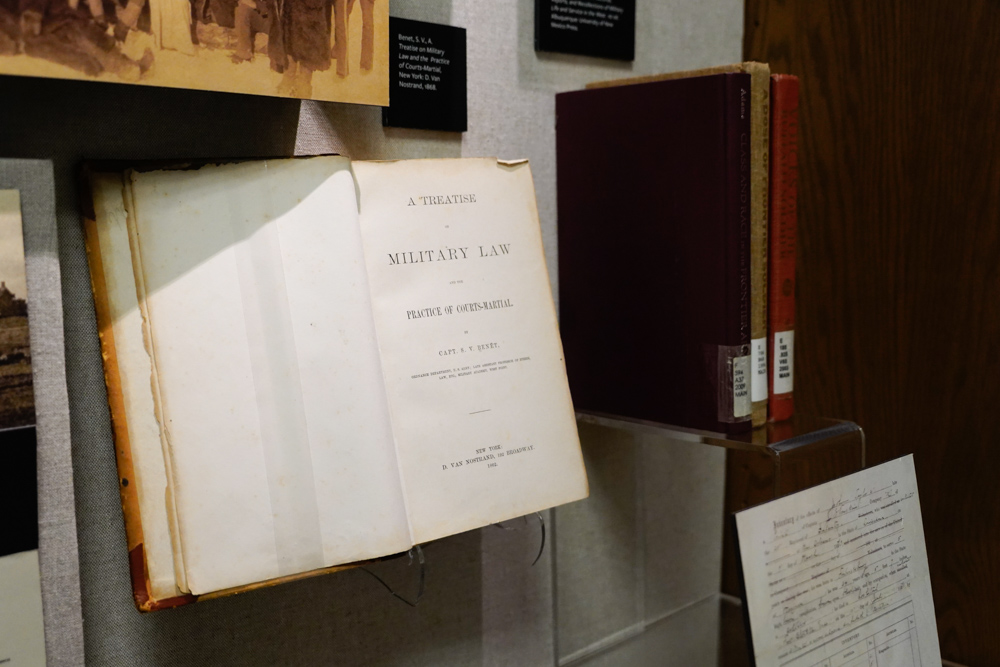

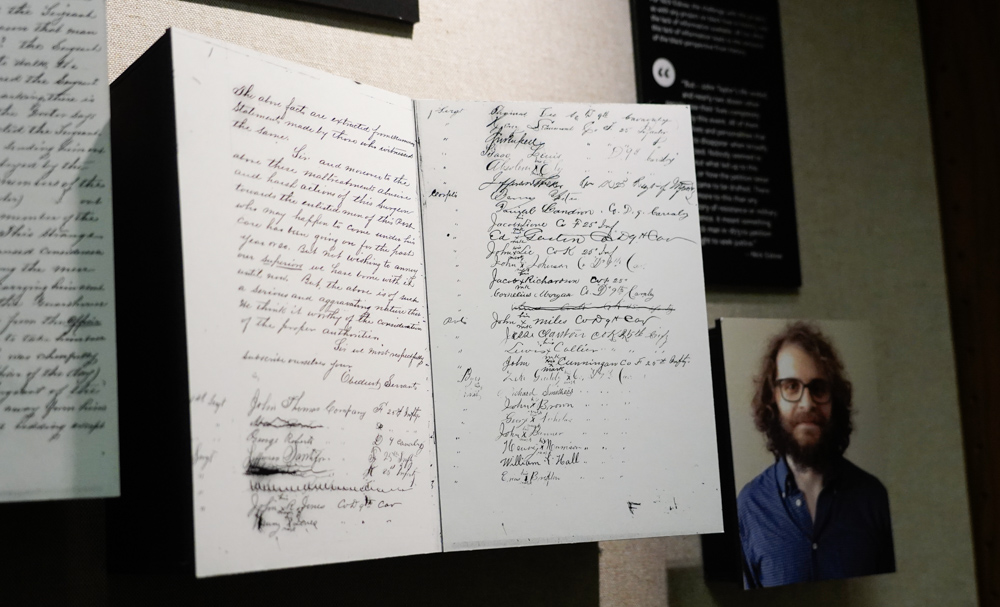

Eskow’s research is also the subject of the rotating Library Prize Exhibit, located on the second floor of Doe Library between Heyns Reading Room and Reference Hall. Drawing on collections held at UC Berkeley, Fort Stockton, Texas, and the National Archives in Washington, D.C., the exhibit displays some of the documents Eskow used to capture the voice of the black soldiers including a digital version of the original petition letter, which includes a few pages of soldiers’ signatures to show the “X” marks by many names. These marks, meant to stand for “his mark,” indicates that many of the soldiers, who were former slaves, could not sign their names and implies that they could neither read nor write. Other documents on display include an 1868 copy of S.V. Benet’s A Treatise on Military Law and Practice of Courts-Martial, which was repeatedly cited by the white officers at Fort Stockton to support their charge against the black soldiers as well as a detailed timeline of the events at Fort Stockton from the death of John Taylor to the sentencing of the twenty soldiers who signed the petition letter.

The Charlene Conrad Liebau Library Prize for Undergraduate Research is awarded annually to UC Berkeley undergraduates. Any course-based research projects completed at UC Berkeley during the award year are eligible. In addition to a monetary prize for winners – $750 for lower division and $1000 for upper division – award recipients as well as honorable mentions will publish their research in eScholarship, the University of California’s open access publishing platform. Two of the winners are also be featured in an exhibit in the Library.

The exhibit – which was curated by Adam Clemons, Librarian for African and African American Studies, and designed by Aisha Hamilton, Exhibits and Environmental Graphics Coordinator – will be up until November 2019.