University Archives

Oral History Center Presents Work at NCPH in Utah and Explores “Belonging” in Japanese American History

In April 2024, Oral History Center (OHC) interviewers Amanda Tewes, Shanna Farrell, and Roger Eardley-Pryor traveled to Salt Lake City, Utah, where we presented our work on the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project at the annual meeting of the National Council on Public History (NCPH). We also joined a pilgrimage to the central desert of Utah along with other public historians and several members of the Wakasa Memorial Committee, including survivors and descendants of the Topaz prison camp in Utah, one of the ten US government mass incarceration sites where Japanese Americans were unjustly imprisoned during World War II. Our experiences in Utah at NCPH and at Topaz reiterated how history remains a powerful and living force, and how oral history can help promote that power. Difficult questions about “belonging” appear throughout many of the oral histories in OHC’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives project, and those same questions punctuated much of our time in Utah this past April.

“Historical Urgency” was the conference theme for this year’s meeting of the National Council on Public History (NCPH) in Salt Lake City, where some 740 attendees presented, networked, and learned together. Presentation topics included community engagement, particularly with communities whose histories face urgent existential threats; communicating the critical importance of history and historical thinking; discourse and dialogue in a time of extreme social polarization; exploration of oral history, especially the collection of oral histories from older generations; and repatriation of human remains and cultural objects. As noted by NCPH president Kristine Navarro-McElhaney, conference discussions highlighted how historians’ work for public audiences remains essential to the fabric of our society, especially during this time of political and cultural polarization—and yet historical perspectives, tools, and history workers themselves have increasingly come under threat. While urgency may seem in opposition to the often slow and deliberate work that oral historians and other public historians do to build trust and lasting relationships with the communities we serve, many of us cannot help but feel a strong sense of urgency and importance in our efforts to collaboratively excavate the past and elevate community stories in ways that help make meaning in the present.

We felt especially honored to share at this NCPH our work on the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project. Our roundtable presentation recounted the project’s origins, the trauma-informed interviewing approach we used with these oral histories, and some of emergent themes from the project’s interviews, like “belonging,” “art and expression,” “healing,” and “memorialization.” The roundtable’s discussion was moderated by Hanako Wakatsuki-Chong, the Executive Director of the Japanese American Museum of Oregon and a former National Park Service Ranger who recorded her own oral history as part of the project. Nancy Ukai and Masako Takahashi, both of whom also recorded oral histories as part of the project, attended and also presented at the NCPH conference in Utah, where they heard portions their own oral history interviews during our presentation. Our presentation included audio clips from season 8 of The Berkeley Remix podcast, “From Generation to Generation”: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration,” as well as graphic narrative artwork by Emily Ehlen, all based on oral histories recorded for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project.

Relatedly, during the NCPH conference, I (Roger Eardley-Pryor) joined other public historians for a tour of the Utah Museum of Fine Arts on the University of Utah campus to see a new exhibit titled Pictures of Belonging: Miki Hayakawa, Hisako Hibi, and Miné Okubo. The exhibition was curated by Professor ShiPu Wang of UC Merced and features over 100 paintings and works on paper by these three Japanese American women artists, all critically acclaimed with long and productive careers. Yet during World War II, both Hibi and Okubo were unjustly incarcerated in Utah at Topaz, along with Hayakawa’s parents. Pictures of Belonging follows the three artists’ prewar, wartime, and postwar art practices, sharing an expanded view of the American experience by women who used artmaking to take up space, make their presence and existence visible, and assert their own belonging. Many of the exhibit’s artworks are on view to the public for the first time. The exhibit’s titular theme of “belonging” resonated nicely with the Oral History Center’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project at UC Berkeley, and Okubo even earned her Master in Fine Arts degree in 1938 from UC Berkeley. Our tour of the art exhibit was co-led by Sarah Palmer, Head Exhibition Designer at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, and by Dr. Kristen Hayashi, Director of Collections Management & Access and Curator at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles. I am especially grateful I could tour Pictures of Belonging with Masako Takashashi, who herself is an outstanding multi-media artist, was born behind barbed wire at the Topaz prison camp in Utah, and who I worked with to record her forthcoming oral history interview for the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project.

Our visit to the Utah Museum of Fine Arts also included another new exhibit titled Chiura Obata: Layer by Layer, which presents an in-depth look at the creation and conservation of Obata’s beautiful “Horses” silk screen painting from 1932. Chiura Obata was an esteemed artist and professor at UC Berkeley who was also incarcerated during World War II at Topaz in Utah, where he and Miné Okubo taught art classes for their fellow Japanese American incarcerees. Kimi Kodani Hill, the granddaughter of Chiura Obata, recently presented at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts on her grandfather’s life and work, and I’m grateful that during our recent meeting in Berkeley, prior to my own Utah trip, she shared stories with me about Obata’s silk screen exhibit. During the screen’s 2022 conservation treatment, conservators at Nishio Conservation Studio discovered that the four-paneled screen contained hidden full-scale preparatory charcoal drawings of the horses. In addition, they found that the screen’s internal layers were made of practice drawings by Professor Obata and his summer 1932 students. The recently conserved screen, the full-scale under-drawings, and a selection of the practice drawings were all on display at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, along with a short film on the conservation process, which itself is an artform. After we returned to the Bay Area, Kimi Kodani Hill provided a guided tour of another exhibition with forty of Chiura Obata’s watercolors, woodblock prints, and ink paintings from several decades of his life that are currently displayed through mid-July at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

On April 11, 2024, in Salt Lake City at the NCPH conference, Masako Takahashi and Nancy Ukai joined other members of the Wakasa Memorial Committee to present their own panel titled “Who Writes Our History?” This panel explored the life and tragic death of James Hatsuaki Wakasa, who was shot and killed while confined in Topaz eighty-one years earlier on April 11, 1943. Their panel also addressed urgent and ongoing challenges over descendant and survivor community consent and collaboration with the Topaz Museum following the recent discovery and excavation of the Wakasa Memorial Stone from the Topaz incarceration site in 2021. That massive, 1,000-pound stone memorial was erected in 1943 by Japanese American incarcerees at Topaz just after James Wakasa’s murder there. But US government authorities quickly demanded the memorial’s destruction in their effort to bury acknowledgement of Wakasa’s death from a bullet fired by a white, nineteen-year-old US soldier who was quickly acquitted of any crime. The Wakasa Memorial Committee’s NCPH presentation, which was standing-room only, featured short films and personal reflections on the life, death, memory, and now-contested stone memorial of James Wakasa.

Two days later, still in Utah, Oral History Center interviewers and several other public historians joined Ukai, Takahashi, and other members of the Wakasa Memorial Committee on a pilgrimage to the dust-strewn ruins of the Topaz site on the edge of the Great Basin in Utah’s central desert. The bus ride out to the remote site included watching historical films and sharing personal backgrounds and reflections amongst this group that had assembled from eight different states. Hours later, we arrived at a sparse, sun-bleached landscape encircled by distant snow-capped mountains. Much of the original barbed wire fence around Topaz remains today where some 8,000 Americans were unjustly imprisoned for years during World War II. Crumbled concrete foundations mark sites of now-gone guard towers where US soldiers aimed their guns down at the Japanese American prisoners, and from where they occasionally fired shots, like the one that pierced James Wakasa’s heart in 1943. At the Topaz site, we joined members of the Topaz Museum Board, including board president Patricia Wakida; Scott Bassett, board secretary and education director at the Topaz Museum; and Topaz descendant and board member Dianne Fukami. Together, we all participated in a ceremony organized by the Wakasa Memorial Committee to commemorate Wakasa’s death, as well as the 140 people who died behind barbed wire at Topaz, and the sixteen Japanese American soldiers drafted from Topaz who died during their World War II military service.

The Wakasa 81st Memorial Ceremony at Topaz began at block 36-7-D, where James Wakasa’s tar-paper barracks once stood. From there, we re-traced Wakasa’s steps across the dusty and now-hauntingly empty landscape to the western perimeter site of his murder, near where the Wakasa Memorial Stone once stood before incarcerated Japanese Americans, under government orders to destroy the memorial, buried it in 1943. An artist’s large recreation of the stone, this one blazing white and made of paper mache and wood, stood near the former burial site of the stone memorial before its removal in 2021. After a land blessing and words of remembrance from survivors born at Topaz, we encircled the artist’s stand-in memorial with name tags bearing the names of our own ancestors. Joshua Shimizu then sang in both Japanese and English the hymn “Rock of Ages,” which was also sung at Wakasa’s funeral in April 1943, and which offered deeper meaning for the missing original Wakasa Memorial Stone.

During the “Rock of Ages” hymn, ceremonial participants attached to the base of the art installation many colorful paper flowers that carried tags naming other Japanese Americans who died in Topaz. The paper flowers we carried to the ceremony were made by Topaz survivors and descendants in honor of the paper floral blossoms folded by imprisoned Japanese Americans at Topaz in lieu of actual flowers for James Wakasa’s 1943 funeral. Miné Okubo, the artist whose work we saw earlier at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, drew several illustrations of Wakasa’s funeral while she was incarcerated at Topaz, including drawings of imprisoned women folding paper flowers to adorn wreaths and crosses. On the desert floor in April 2024, white paper flowers also surrounded the excavation site where the Topaz Museum Board excavated Wakasa’s Memorial Stone in 2021. The Wakasa 81st Memorial Ceremony at Topaz simultaneously evoked absence and living memory. It was especially meaningful to me (Roger) to join Nancy Ukai and Masako Takahashi at the ceremony after having worked together to record their oral histories, in which they shared intergenerational memories about James Wakasa and more recent memories about the Wakasa Memorial Stone’s recent rediscovery and removal from that site.

After the ceremony at Topaz, the pilgrimage group boarded the bus and traveled sixteen miles to the handsome Topaz Museum, which opened in 2017 after decades of fundraising and planning in the small town of Delta, Utah. Once there, the pilgrimage group found their way to the back of the museum where we gathered to witness the actual Wakasa Memorial Stone, a one-thousand-pound rock now confined in a small enclosure. After paying our respects to the stone, we toured the Topaz Museum’s exhibits and collections, which include hundreds of artifacts, photographs, and oral histories, as well as 150 pieces of original artwork. The Topaz Museum’s core exhibit explores the complex story of the World War II Japanese American incarceration experience, especially as it transpired at Topaz. The exhibit begins with the racist laws that marginalized early Japanese immigrants, which lead eventually to the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. The exhibit extends into the traumatic impacts of their exile, with an obvious focus on the Topaz experience, and it concludes with an examination of the Constitutional violations that the incarcerees were forced to endure. I found the Topaz Museum exhibits to be impressive, interactive, and informative. The pilgrimage group then gathered a final time out back by the Wakasa Memorial Stone before boarding the bus and returning to Salt Lake City.

The emotional experiences throughout our time in Utah reminded me of William Faulkner’s line in Requiem for a Nun: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” The public history presentations on “historical urgency” at NCPH, the outstanding exhibits on Japanese American artists, the powerful pilgrimage to Topaz and the commemorative ceremony at the site of James Wakasa’s murder, which we shared with survivors and descendants of the prison camp eighty-one years from the date of Wakasa’s death, as well as our trip to the Topaz Museum to see its exhibits and the excavated Wakasa Memorial Stone all reminded us that history is still very much alive and shapes our present experiences. At both the Topaz incarceration site and at the Topaz Museum in Delta, we witnessed some of the still-simmering tensions between Topaz Museum Board members and members of the Wakasa Memorial Committee over what has happened and what will happen to the now-unearthed Wakasa Memorial Stone. Throughout all of those experiences in Utah, I kept thinking on the recurrent theme of “belonging,” including in the oral histories we continue to conduct in the Oral History Center’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project. “Belonging” carries multiple meanings and invites complex questions. Within what communities, or within which factions of communities, do we find and feel belonging? Throughout history, and up through the present, where have Japanese Americans found belonging? What about the physical artifacts of Japanese American history, like artwork created during World War II-era incarceration, or like the recently re-discovered Wakasa Memorial Stone? To whom do those objects belong? And importantly, who has the right to tell the history of artifacts, artwork, memorials, or lived experiences? To whom does this history belong?

Answers to questions of belonging are elusive because they’re always evolving. I do know, however, how grateful I feel to continue working with individuals and communities to record oral histories that empower narrators to share their own living memories and reflections on the past, and how the personal histories these interviews record will continue to shape our shared present moments. These experiences in Utah helped further inspire our ongoing work on the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project. We hope that you, too, can find inspiration and meaning in these stories, and that they might inform your own sense of belonging.

— Roger Eardley-Pryor, Oral History Center historian and interviewer

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center if you’d like to see more work like this conducted and made freely available online. While we receive modest institutional support, we are a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. We must raise the funds to cover the cost of all the work we do, including each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

Bancroft Quarterly Processing News

The archivists of The Bancroft Library are pleased to announce that in the past quarter (July-September 2023) we opened the following Bancroft archival collections to researchers.

General and UARC Collections:

Michael Paul Rogin papers (processed by Marjorie Bryer)

Acción Latina records and El Tecolote newspaper archive (processed by Marjorie Bryer)

Pam Levinson papers (processed by Presley Hubschmitt)

William Moore journals and other papers (processed by Lara Michels)

Renee Gregorio papers (processed by Simi Best)

Howard A. Brett collection of Panama Canal materials (processed by Lara Michels)

C. (Walter Clay) Lowdermilk papers (processed by Presley Hubschmitt)

Mosaic Law Congregation records (processed by Presley Hubschmitt)

Daniel Holmes collection of Sierra Club burro trips and Yosemite National Park backcountry research (processed by Jaime Henderson)

Triangle Gallery records (processed by Dean Smith)

Western Jewish History Center records (processed by Presley Hubschmitt)

Bransten and Rothmann family papers (processed by Presley Hubschmitt)

Friends of the River collection (transfer from UC Riverside; additional processing work by Lara Michels and Jaime Henderson)

George W. Barlow papers (processed by Jessica Tai)

Streetfare Journal records (processed by Lara Michels and student processing assistant Malayna Chang)

Roger Parodi collection of art museum and gallery announcements (processed by Lara Michels and student processing assistant David Eick)

Israel Louis Greenblat papers (processed by Presley Hubschmitt)

American Cultures Center records (processed by Jessica Tai)

Larry Orman archive of The Friends of the Stanislaus River materials (processed by Jaime Henderson)

Hamilton Boswell papers (digital materials processed by Christina Velazquez Fidler)

Pictorial Collections:

130 small collections and single items (approximately 6,650 items, total)

William F. Knowland’s gubernatorial campaign of 1958 photographs (and miscellaneous subjects added in Series 4 of the Lonnie Wilson archive)

3,155 new scans from Thérèse Bonney’s WWII era photographs from Finland, 1939, and France, Portugal, Belgium 1940

Collections Currently in Process:

Elizabeth A. Rauscher papers (Jessica Tai)

Associated Students of the University of California, Berkeley, records (Jessica Tai)

California Faience archive (Jaime Henderson)

Jan Kerouac papers (Marjorie Bryer)

Sister Makinya Sibeko-Kouate papers (Marjorie Bryer)

Nathan and Julia Hare papers (Marjorie Bryer)

Morris M. Goldstein papers (Presley Hubschmitt)

Hertzmann and Koshland family papers (Presley Hubschmitt)

Bush Street Synagogue Cultural Center records (Presley Hubschmitt and student processing assistant Malayna Chang)

Charles Muscatine papers–digital component (Christina Velazquez Fidler)

ruth weiss papers (Simi Best)

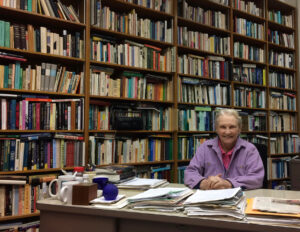

“Carolyn Merchant: My Life Exploring Science, Environment, and Ethics,” oral history release

New oral history: “Carolyn Merchant: My Life Exploring Science, Environment, and Ethics”

Video clip from Carolyn Merchant’s oral history on the 1970s social contexts for her book The Death of Nature

Carolyn Merchant is a Distinguished Professor Emerita of Environmental History, Philosophy, and Ethics at UC Berkeley. Her extensive research and teaching at Cal explored historical relationships between humanity, nature, and science with an ecofeminist focus on Western culture’s domination of nature and women. Throughout her academic career, Merchant published numerous peer-reviewed articles and wrote eleven books, as well as four edited volumes. Her genre-shaping publications—including The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution (1980); Ecological Revolutions: Nature, Gender, and Science in New England (1989); Radical Ecology: The Search for a Livable World (1992), among others—influenced various academic fields from Women’s Studies to the History of Science, and from Ethics to Environmental History.

Merchant and I video-recorded seven hours of her oral history over four interview sessions in the spring of 2022. Those recordings resulted in a 132-page transcript that includes an appendix with photographs. Merchant’s full-life oral history not only explored her intellectual and academic career, but also recorded lesser known details from her female-centered childhood, her educational mentors, her personal relationships, and her social activism, all of which shaped her academic research and teaching at UC Berkeley.

Merchant was born in 1936, in Rochester, New York, where she and her younger sister were raised by their mother, grandmother, and aunt. Merchant recalled how sharing a home with five strong women taught her that “women could do anything. …That gave me a role model unconsciously to know that I could do anything I wanted to.” As a high school senior in 1954, Merchant became a national top ten finalist in the Westinghouse Science Talent Search. She earned her AB in Chemistry from Vassar College in 1958, studied physics for a year at the University of Pennsylvania, and then, at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, she earned her MA in 1962 and her PhD in 1967 in the History of Science. Her graduate research explored the Vis Visa controversy in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries over a “living force” in nature, from Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz to Jean-Baptiste le Rond D’Alembert.

Video clip from Carolyn Merchant’s oral history on learning and teaching the history of science, 1960s and 1970s

During graduate school in Wisconsin, Merchant met and married botanist Hugh Iltis, with whom she had two sons, both of whom later graduated from UC Berkeley. Merchant also began her environmental activism during graduate school, which included lighting Wisconsin prairies on fire as a means to restore native plants and animal habitat. At that time, Merchant first read Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique and Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, which affected both her life and academic trajectories. In the late 1960s, upon completing her PhD thesis and her divorce from Iltis, Merchant and her sons moved from Wisconsin to Berkeley, California.

Merchant’s life on the west coast provided new opportunities and realizations. While teaching the History of Science as a Visiting Lecturer at Oregon State University, Merchant lived on a Corvallis farm where the runner-up Dairy Queen of the state of Oregon taught her how to milk goats and cows. Merchant’s back-to-the-land experiences would shape her later analysis on utopias and what she described as the “organic society,” from John Salisbury’s organic concept of the state in 1159, to Francis Bacon’s The New Atlantis in 1627. To support herself and her family back in Berkeley, Merchant worked as an adjunct instructor, which she eventually parlayed into a fulltime position. She taught as a Lecturer at the University of San Francisco, where by 1976 she became an Assistant Professor, and she also taught in the innovative, interdisciplinary, yet short-lived Strawberry Creek College program at UC Berkeley.

Throughout the 1970s in the Bay Area, Merchant engaged in feminist, environmental, anti-war, and anti-capitalist politics, which is how she first met UC Berkeley historian Charles Sellers, whom she later married. Over many decades together, Merchant and Sellers advocated for social justice and shared adventures traversing the United States in a camper van while searching for rare birds and visiting far flung archival collections. On the road, Merchant used some of the first laptop computers to draft her eventual publications. Back in the Bay Area, Merchant connected with intellectuals like Theodore Roszak and became a visiting scholar at Stanford’s Center for Advanced Study in Behavioral Sciences. Around that time, Merchant learned from a USF colleague that UC Berkeley planned to hire a professor to work in the then-nascent field of environmental history. “I can do that,” she said to herself, and walked up the hill from her house to campus to submit her application. As she recalled, “when I was interviewed, I was from Stanford, and I was not a local yokel four blocks away in Berkeley where my house actually was.”

Video clip from Carolyn Merchant’s oral history on her hiring at UC Berkeley’s College of Natural Resources, 1980

Women played a central role in Merchant’s research, as well as with her hiring at UC Berkeley in 1979. Merchant applied to the College of Natural Resources for a position in a new department then called Conservation and Resource Studies, which later became the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management. On the hiring committee were five male faculty members and five female undergraduates. Many women took courses in the college, yet the faculty of the College of Natural Resources were still mostly men. After her on-campus interview, Merchant recalled “the students wanted a woman, and they lobbied. …They wanted to understand what role women had played in the environment, and how they used the environment, and how they developed as scientists and environmental scientists. And they liked me because I was interested in pursuing those topics and finding out by digging into the archives who the women were and what they had done.” The first three hires for the new department were all women. In 1980, one year after Merchant joined the faculty at UC Berkeley, she published The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution, which remains in print today and has been translated into numerous languages. As Merchant recalled, when the book appeared, “there was a column in Newsweek, and then it was brought up at a congressional hearing. It [my book] was a criticism of what mechanistic science alone would do to the environment if it wasn’t associated with an ethic and some restraints and understanding of what the consequences were. So it was very gratifying to see that reception.”

The majority of Carolyn Merchant’s oral history explores her career as a Professor of Environmental History, Philosophy, and Ethics at UC Berkeley. The topics we discussed ranged from the evolution of Merchant’s research and teaching to her reflections on how the College of Natural Resources has changed over time. Generally, Merchant’s research and teaching examined the history and ethics of science and the environment through the lens of gender. As she noted during her oral history, “gender is so important and so central. Because most of human history, and most of even environmental history and the history of science, has been concerned with the roles that men play. And I want to make the roles that women play and the importance of gender as an equal thing, so that the roles of women are not obscured—and that women and men are equal partners not only in an existing political economy and a social economy, but they are equal partners in every aspect of trying to work together as partners to make the whole planet continue to live on.”

Video clip from Carolyn Merchant’s oral history on gendered reproduction

In her oral history, Merchant also addressed some of the specific, interrelated research themes that she developed throughout her career. One of those themes focused on science and domination, especially Merchant’s attention to impacts on nature as both a mental construct and a physical reality when institutions of science emerged within a patriarchal society. She also spoke about women and nature through the lens of ecofeminism. “Ecofeminism comes from a woman named Françoise d’Eaubonne in France,” Merchant explained. “Ecofeminism asserts the power of women and also their interrelationships with nature, and how women can save nature, and how women themselves can become important forces in the whole role of the conservation of resources.” Merchant discussed her partnership ethic, a contribution she made to environmental ethics in which humans of all genders, along with nonhuman nature, would be valued as equal partners inhabiting a flourishing earth. “Partnership makes nature and humans equal, and interactive, and sharing and giving,” Merchant declared, “and we have to conserve nature if we are going to go ahead and live in the future with an active nature and an active humanity.” In light of her own politics to protect and conserve nature, Merchant also reflected on about the importance of gendered reproduction, and how control of women’s bodies and the unpaid labor of those bodies are essential to the material, social, and cultural maintenance of a capitalist and patriarchal society. In contrast to the modern world’s focus on production, Merchant emphasized the need for reproduction: “allowing the reproduction of nature and its systems to continue is what is going to allow humanity to reproduce itself and to continue. …Because if we don’t allow the natural resources of the world to keep reproducing themselves, if we don’t set aside land or pass laws that prevent us from using everything up, we won’t be able to continue reproduction.”

Carolyn Merchant’s oral history is now available to read online, even as the ever-worsening impacts of climate change create an interrelated set of crises for the Earth and all living organisms on it, including humanity. After her long career teaching and researching environmental topics at UC Berkeley, Merchant admitted, “of course, I’m distressed that we have all the environmental problems that we have now.” Yet, in the face of these crises, she also shared her optimism. “There’s also hope in the sense that there are laws being passed, there are people who are working continuously, and there are new societies and new organizations being formed. So we’re at a tipping point. And hopefully, we’ll go in the direction of conservation, and environmental justice, and environmental reform, and saving the Earth.”

Carolyn Merchant’s oral history is now available to read online, even as the ever-worsening impacts of climate change create an interrelated set of crises for the Earth and all living organisms on it, including humanity. After her long career teaching and researching environmental topics at UC Berkeley, Merchant admitted, “of course, I’m distressed that we have all the environmental problems that we have now.” Yet, in the face of these crises, she also shared her optimism. “There’s also hope in the sense that there are laws being passed, there are people who are working continuously, and there are new societies and new organizations being formed. So we’re at a tipping point. And hopefully, we’ll go in the direction of conservation, and environmental justice, and environmental reform, and saving the Earth.”

Video clip from Carolyn Merchant’s oral history on her partnership ethic for humanity and nature

Video clip from Carolyn Merchant’s oral history on becoming a national finalist in the Westinghouse Science Talent Search, 1954

ABOUT THE ORAL HISTORY CENTER

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library preserves voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public. You can find our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

If you’d like to see more interviews like this conducted and made freely available online, please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Oral History Center. While we receive modest institutional support, we are a predominantly self-funded research unit of The Bancroft Library. We must raise the funds to cover the cost of each oral history. You can give online, or contact us at ohc@berkeley.edu for more information about our funding needs for present and future projects.

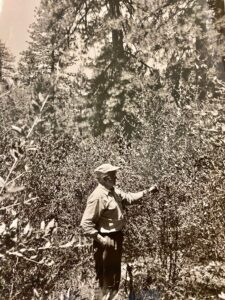

Changing the Course of Wildfire Management in California: Highlights from the Harold Biswell Papers

The Harold H. Biswell papers are now open to researchers at the Bancroft Library. Harold H. Biswell (1905-1992) served as a faculty member in the School of Forestry from 1947 to 1973. Biswell was a researcher, teacher, and advocate of the use of prescribed burning for fire management. Prescribed burns are intentionally-set fires for purposes of forest management, fire suppression, farming, prairie restoration or greenhouse gas abatement. The Biswell papers include photographs and slides of controlled burns and survey images of California forests, chaparral, and ranches. The collection also contains articles by Biswell and others, reports, booklets, survey and research material, School of Forestry theses, and other material related to controlled burning and forest ecology.

Indigenous peoples were the first to use cultural burning for managing vegetation and wildlife habitats. “Cultural burning” refers to the Indigenous practice of intentionally setting fires in alignment with traditional belief and knowledge systems to revitalize habitats or provide a desired cultural service, such as promoting the health of vegetation and animals that provide food, clothing, ceremonial items and more. These practices were disrupted by European colonization and forced relocation of Indigenous communities from the lands they had been maintaining for centuries. In 1850, California passed the Act for the Government and Protection of Indians, which outlawed intentional burning. These bans, guided by a strategy of fire suppression, led the way for a rapid increase in destructive wildfires, as well as the inability for Indigenous people to practice traditional cultural burning practices.

Despite opposition and direct criticism, Biswell continually advocated for developing new policies for prescribed burning. Biswell staked his academic reputation on demonstrating that prescribed burns improved ecosystem health and reduced wildfire threats. The Forest Service began to examine its fire exclusion policy in the early 1970’s, and in 1978 the national policy was changed to encompass total fire management including prevention, suppression, and use. Prescribed burns are now recognized as a critical tool to reduce the severity of wildfires.