Tag: “The Languages of Berkeley”

American Sign Language

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

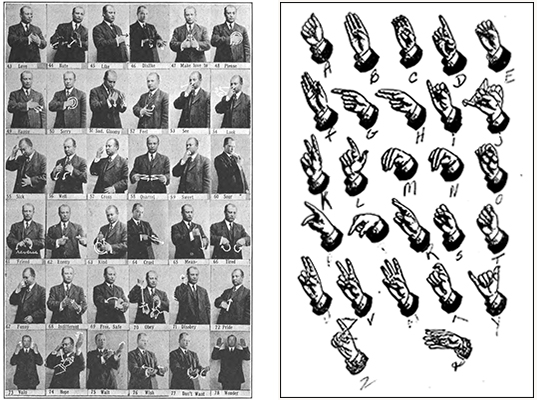

The significance of J. Schuyler Long’s The Sign Language; A Manual of Signs, Being A Descriptive Vocabulary of Signs Used by the Deaf of The United States and Canada cannot be separated from the status of Deaf education at the beginning of the 20th century. Beginning in 1880 at the Second International Congress of the Deaf, educators of the Deaf adopted the practice of oralism, which relied solely on speech to teach the Deaf and forcing them to learn skills such as lip reading. Many in the Deaf community viewed this as an attempt to eradicate sign language in an attempt to forcibly assimilate them into the hearing community.[1] As a result of this forced adoption, fewer Deaf instructors were proficient in American Sign Language (ASL), and fewer children were learning the language fluently.

In response, various Deaf educators took the initiative of documenting ASL, taking advantage of these new formats of photography and film to document and preserve the language. J. Schuyler Long, principal at the Iowa School for the Deaf and a graduate of Gallaudet University, developed in 1910 and reprinted in 1918 a handbook of signs used in ASL, incorporating detailed written descriptions of each sign with photographs illustrating each vocabulary term. For example, for the sign “fascinate”, Long describes the motions as such:

Fascinate — Bring the hand up before the face, with fingers extended except the thumb and forefinger which are brought together as if about to grasp something; bring them nearly together and then draw out slowly from the face (giving the idea of drawing the attention out), giving the face an intent or concentrated look.[2]

Long’s manual also firmly states that ASL is indeed a language, with established vocabulary and dialectical variation. This argument helped Deaf activists show that ASL is more than pantomime.

Today, American Sign Language is one of the languages taught at UC Berkeley. Though it was not established as a language course until 2012, students are now able to take ASL to fulfill the language requirement in their degree programs.[3] Even if students are not enrolled in the course, they can still find ways to learn the language, thanks to the evolution of image based media such as YouTube. Thanks to the efforts of educators and activists, students can understand ASL as not just a series of gestures, but as its own complex language.

Contribution by Natalia Estrada,

Reference and Collections Assistant, Social Sciences Division, The Library

Sources consulted:

- Jankowski, K. A. Deaf Empowerment: Emergence, Struggle, and Rhetoric. Washington, D.C: Gallaudet University Press, 1997.

- Long, J. S. The Sign Language; A Manual of Signs, Being A Descriptive Vocabulary of Signs Used by the Deaf of The United States and Canada (2nd ed. reprint). Washington: Gallaudet College, 1969 [©1952].

- Cockrell, Cathy. “ASL Language Courses a Sign of the Times at Berkeley,” Daily Californian (September 20, 2012).

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: The Sign Language; A Manual of Signs, Being A Descriptive Vocabulary of Signs Used by the Deaf of The United States and Canada

Author: Joseph Schuyler Long, 1869-1933.

Imprint: Washington, Gallaudet College, 1969 [©1952].

Edition: 2d ed., rev. and enl.

Language: American Sign Language

Language Family:

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Michigan)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001743786

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

German

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Although based on a legend transmitted through the popular literature and drama of German-speaking Europe from the late 16th century onward (and which found an English-speaking audience through translation of the texts and Christopher Marlowe’s dramatic adaptation), Goethe’s own version of Faust lives at the heart of the German literary canon. The play’s “pact with the Devil” narrative tells the story of Dr. Faust, who, seeking deeper knowledge than the academy can provide, strikes a bargain with Mephistopheles which requires him to serve Faust and to show him all of the truths in the world. However, should Faust ever become complacent, his life would be forfeit. A series of fantastic, and tragic, events follows, and in the end Faust finds that his life is at risk.

Goethe calls upon a variety of meters to tell his tale, which combines elements of contemporary European society with classical themes. He worked on the play intermittently over the course of nearly 50 years beginning in the 1770s (from which a copied manuscript survives), and after releasing his early efforts as Faust, ein Fragment in 1790, decided that the full play should be published as two parts: Part I, published in 1808, and Part II, published posthumously in 1832. Goethe’s Faust would become highly influential, inspiring music, theater, opera, film, and literature (including Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita) from the 19th century to the present. UC Berkeley Library owns numerous editions of the text, including the initial 1790 publication which was included in a multi-volume set of Goethe’s collected works and is housed in The Bancroft Library. A new project funded by the German Research Foundation called Faustedition has made Faust even more accessible by putting the full text online, and allowing line-by-line reading of variations across editions. Importantly, the project also includes an online archive of Goethe’s handwritten papers and letters, transcribed and searchable, which are related to the development of Faust.

The German language and its literature have been a fixture at Berkeley since the university’s founding. Today, the German Department offers courses at all levels and encompassing the breadth of the Middle Ages to the 21st century. In addition to Modern German, earlier forms of the language including Old Saxon, Old High German, Middle High German, and Early New High German are all taught. Goethe’s writings continue to be studied and read extensively.

Contribution by Jeremy Ott

Classics and Germanic Studies Librarian, Doe Library

Title: Faust

Title in English: Faust

Author: Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von, 1749-1832.

Imprint: Leipzig: Christian Friedrich Solbrig, 1790.

Edition: 1st [?]

Language: German

Language Family: Indo-European, Germanic

Source: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) | German Research Foundation

URL: http://faustedition.net

Other online editions:

- Faust. Eine Tragödie von Goethe. Zweyter Theil in fünf Acten. (Vollendet im Sommer 1831). Stuttgart und Tübingen, J.G. Cotta, 1833.

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Goethe’s Schriften. 8 vols. Leipzig, G. J. Göschen, 1787-90.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Filipino (Tagalog)

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

“Tagalog, or Filipino, is said to mean ‘river people’ from taga- ‘place of origin’ and ilog “river,'” writes the linguist and historian Andrew Dalby. Already a language of written culture in the region of Manila on the island of Luzon when the Spanish invaded in the late 16th century, Filipino spread across the Philippine archipelago over thousands of years and was declared the first official language in the 1940s when independence from the United States was in sight.”[1]

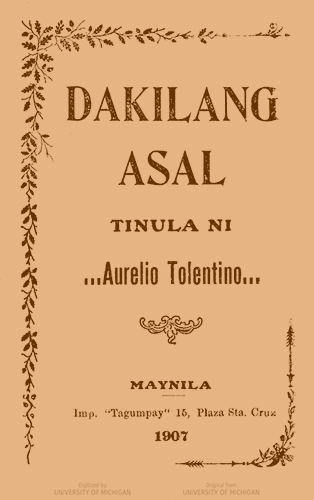

During the Spanish colonial period, publishing in Filipino and other indigenous languages was largely religious in inspiration while incorporating distinctive Tagalog poetic forms. One of Aurelio Tolentino’s most famous works of verse, Dakilang Asal (“Noble Behavior”) is a series of ten didactic poems conveying a code of upright moral conduct meant to instruct the lives of Filipino youth. Presented as the basis for a buhay ng lahat ng dunong (life of all wisdom), Tolentino emphasizes key ethical virtues that remain prominent in Filipino culture, i.e. parental reverence, utang na loob (debt of gratitude), cleanliness, modesty, and humility.

The Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies (SSEAS) at UC Berkeley offers both undergraduate and graduate instruction and research in the languages and civilizations of South and Southeast Asia from the most ancient period to the present. Instruction includes intensive training in several of the major languages of the area including Bengali, Burmese, Hindi, Khmer, Indonesian (Malay), Pali, Prakrit, Punjabi, Sanskrit (including Buddhist Sanskrit), Filipino (Tagalog), Tamil, Telugu, Thai, Tibetan, Urdu, and Vietnamese, and specialized training in the areas of literature, philosophy and religion, and general cross-disciplinary studies of the civilizations of South and Southeast Asia.[2] Outside of SSEAS where beginning through advanced level courses are offered in Filipino, related courses are taught and dissertations produced across campus in Asian American Studies, Comparative Literature, Ethnic Studies, Folklore, History, Linguistics, and Political Science (re)examining the rich history and culture of the Philippines.[3]

Contribution by Gabrielle Pascua,

Undergraduate, Department of History

Sources consulted:

- Dalby, Andrew. Dictionary of Languages: The Definitive Reference to More Than 400 Languages. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998.

- Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies, UC Berkeley (accessed 6/18/19)

- Filipino (FILIPN) – Berkeley Academic Guide (accessed 6/18/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Dakilang Asal

Title in English: Noble Behavior

Author: Tolentino, Aurelio, 1867-1915.

Imprint: Maynila : Imp. Tagumpay, 1907.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Filipino (Tagalog)

Language Family: Austronesian, Malayo-Polynesian

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Michigan)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/003560966

Other online editions:

- Project Gutenberg, http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/13687

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Portuguese (Brazil)

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

“A imaginação foi a companheira de toda a minha existência, viva, rápida, inquieta, alguma vez tímida e amiga de empacar, as mais delas capaz de engolir campanhas e campanhas, correndo.”

“Imagination has been the companion of my whole existence — lively, swift, restless, at times timid and balky, most often ready to devour plain upon plain in its course.” (trans. Helen Caldwell p. 41, Dom Casmurro)

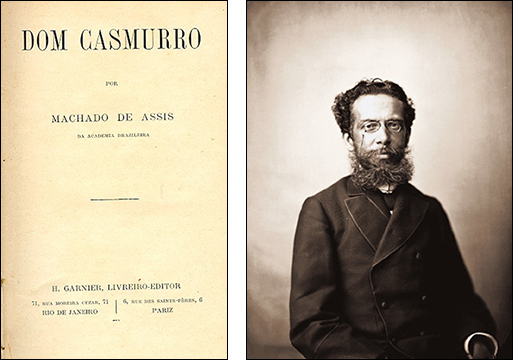

The novel Dom Casmurro is considered a masterpiece of literary realism and one of the most significant works of fiction in all of Latin American literature. The late Brazilian literary critic Afrânio Coutinho called it possibly one of the best works written in the Portuguese language, and it has been required reading in Brazilian schools for more than a century.[1] At UC Berkeley, generations of students in literature courses have been enjoying the rich complexity of this work of prose since the 1950s when the author began receiving recognition worldwide. Indelibly influenced by French social realists such as Honoré de Balzac, Gustave Flaubert and Émile Zola, Dom Casmurro is a sardonic social critique of Rio de Janeiro’s bourgeoisie. The satirical novel takes the reader on a terrifying journey into a mind haunted by jealousy via an unreliable first-person narrative told by Bento Santiago (Bentinho) who suspects his wife Capitú of adultery.

Dom Casmurro was written by multiracial and multilingual Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis (1864-1908) who was an essayist, literary critic, reporter, translator, government bureaucrat. He was most venerated for his short stories, plays, novellas, and novels which were all set in his milieu of Rio de Janeiro. The son of a freed slave who had become a housepainter and a Portuguese mother from the Azores, he grew up in an affluent household under a generous patroness where his parents were agregados (domestic servants).[2] A prodigy of sorts, he began writing at an early age, and quickly ascended the socio-cultural ladder in a country that did not abolish slavery until 1888 with the Lei Áurea (Golden Act).[3] At the center of a group of well-known poets and writers, Machado founded the Academia Brasileira de Letras (Brazilian Academy of Letters) in 1896, became its first president, and was perpetually reelected until his death in 1908.[4] “Even more remarkable than Machado’s absence from world literature,” wrote Susan Sontag, “is that he has been very little known and read in Latin America outside Brazil — as if it were still hard to digest the fact that the greatest author ever produced in Latin America wrote in the Portuguese, rather than the Spanish, language.”[5]

With a population of over 210 million, Brazil has eclipsed Portugal and its former colonies in Africa and Asia and now constitutes more than 80 percent of the world’s Portuguese speakers. Portuguese is the sixth most natively spoken language globally.[6] While European Portuguese (EP) is considered a less commonly taught language in American universities, this is not the case for Brazilian Portuguese (BP) where it has become increasingly popular. The Modern Language Association’s recently released study on languages taught in U.S. institutions, ranked Portuguese as the eleventh most taught language.[7] BP and EP are the same language but have been evolving independently, much like American and British English, since the 17th century. Today, the linguistic variations (phonetics, phonology, syntax, morphology, semantics, pragmatics) are so stark that a non-fluent observer might mistake the two for entirely different languages. In 1990, all Portuguese-language countries signed the Acordo Ortográfico da Língua Portuguesa — a treaty to standardize spelling rules across the Lusophone world — which went into effect in Brazil in 2009 and in Portugal in 2016.[8]

At Berkeley, Brazilian literature is offered for all periods and levels of study through the Department of Spanish and Portuguese’s Luso-Brazilian Program directed by Professor Candace Slater.[9] Her research centers on traditional narrative and cordel ballads, and she was awarded the Ordem de Rio Branco in 1996 — the highest honor the Brazilian government accords a foreigner — and in 2002, the Ordem de Merito Cultural. Other Brazilianists in the department include professors Natalia Brizuela and Nathaniel Wolfson. Graduate students with an interest in Brazil who are part of the Hispanic Language and Literatures (HLL), Romance Language and Literatures (RLL), and Latin American Studies programs delve into all aspects of the nation’s history, culture, and language.[10]

Contribution by Claude Potts

Librarian for Romance Language Collections, Doe Library

Sources consulted

- Coutinho Afrânio. Machado de Assis na literatura brasileira. Academia Brasileira de Letras, 1990.

- “More on Machado,” Brown University Library’s Brasiliana Collection. (accessed 7/19/19)

- Rodriguez, Junius P. Encyclopedia of Emancipation and Abolition in the Transatlantic World. Armonk, NY: Sharpe Reference, 2007.

- Preface to Dom Casmurro: A Novel by Machado de Assis. Translated by Helen Caldwell. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966, c1953.

- Sontag, Susan. “Afterlives: the Case of Machado de Assis,” New Yorker (April 29, 1990).

- CIA World Factbook (accessed 7/19/19)

- Modern Language Association of America. Enrollments in Languages Other Than English in United States Institutions of Higher Education, Summer 2016 and Fall 2016: Final Report (June 2019). (accessed 7/19/19)

- Vocabulário Ortográfico da língua portuguesa. 5a ed. São Paulo, SP : Global Editora ; Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil : Academia Brasileira de Letras, 2009; and Academia das Ciências de Lisboa. Vocabulário ortográfico atualizado da língua portuguesa. Lisboa : Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda, 2012.

- Portuguese (PORTUG) – Berkeley Academic Guide (accessed 7/26/19)

- Hispanic Languages & Literatures, Romance Languages and Literatures, Latin American Studies, UC Berkeley (accessed 7/25/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Dom Casmurro

Title in English: Dom Casmurro : novel

Author: Machado de Assis, Joaquim Maria, 1839-1908.

Imprint: Rio de Janeiro; Paris: Garnier, 1899.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Portuguese

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil

URL: http://acervo.bndigital.bn.br/sophia/index.asp?codigo_sophia=4883

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- O romance Dom Casmurro de Machado de Assis / Maximiano de Carvalho e Silva. Niterói : Editora da UFF, 2014. Includes the reproduction of the 1899 edition.

- Dom Casmurro. Ilustrações, Carlos Issa ; posfácio, Hélio Guimarães. São Paulo, SP : Carambaia, 2016.

- Dom Casmurro : A Novel. Translated from the Portuguese by John Gledson ; with a foreword by John Gledson and an afterword by João Adolfo Hansen. Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Dom Casmurro: A Novel by Machado de Assis. Translated by Helen Caldwell. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966, c1953.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Wolof

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Wolof is the most widely spoken African language in Senegal, predominantly in urban areas. It is also spoken in the West African nations of Mauritania and The Gambia. Within Senegal, approximately 40% of the total population (just over 15 million according to World Bank estimates) are native speakers while the majority of the rest speak it as a second language. In Mauritania, Wolof is spoken by approximately 7% of the total population (estimated at just over 4 million by the World Bank), though the majority of speakers reside in the southernmost part of the country nearest the border with Senegal. About 3% of the total population of The Gambia (estimated at just over 2 million according to the World Bank) speak Wolof but it tends to be disproportionately influential in the country because of its prevalence in Banjul, Gambia’s largest city. Wolof is part of the Senegambia branch of the of the Niger-Congo language family, of which there are some 1,500 other languages.

Démbi Senegaal: ci làmmeñu Wolof is an account of the history of Senegal from antiquity through the end of the 19th century. By retracing these historical events, Paate Sow’s intent is to inform Wolof readers about the unique histories — political, economic, social — of the kingdoms (Jolof, Kajor, Waalao, etc.) that makeup what is today known as Senegal. Though not as culturally significant in the same way as say, Mariama Bâ’s Une si longue lettre, Paate Sow’s Démbi Senegaal: ci làmmeñu Wolof is a rare example of a title published in Wolof and available electronically. Finding titles that met this criteria — published in Wolof while also electronically available — was exceedingly difficult for all African languages represented in this exhibit. Thanks to projects like Céytu, which aims to publish — both in print and electronic form — the major works of literature from the Francophone world in Wolof, finding electronic versions of important works in African languages should be easier.

Wolof was offered for nearly a quarter century to students who could take elementary to advanced-level Wolof under the direction of instructor Alassane Paap Sow. He taught Wolof at UCB for over 20 years, and also developed material in Wolof through the BLC’s Library of Foreign Language Film Clips (LFLFC), a tagged, structured collection of clips from films and searchable database. Additionally, the Center for African Studies pioneered distance learning in the UC system by offering courses in Wolof (as well as Swahili). Wolof has not been offered at UC Berkeley since 2015 due to lack of funding.

Contribution by Adam Clemons

Librarian for African and African American Studies, Doe Library

Title: Démbi Senegaal: ci làmmeñu Wolof

Title in English: n/a

Author: Paate Sow

Imprint: Dakar : Info-edit, 1998.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Wolof

Language Family: Niger-Congo

Source: ALMA Project (African Language Materials Archive Project) of WARC (West African Research Center)

URL: http://www.dlir.org/docs/alma_ebooks/wolof_009.pdf

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Sanskrit

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

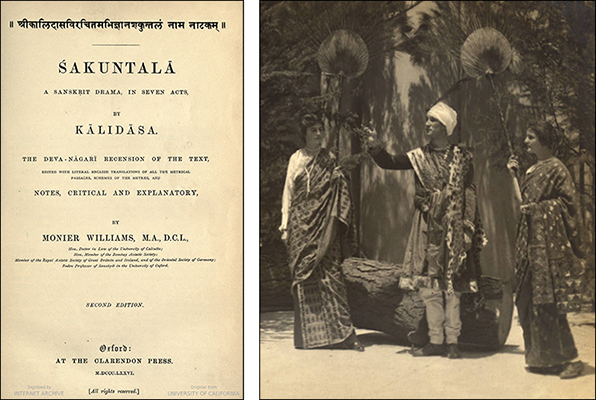

There is little doubt that Kālidāsa is one of the most celebrated poets not only in Sanskrit literature but in all of South Asian history. His works represent the acme of Sanskrit poetry and became the model for subsequent poets in Sanskrit as well as most of the major languages of the region. Despite his celebrity and the reverence for his works, very little is definitively known about Kālidāsa. Based on tradition and meagre references to his own life in his works, most scholars agree that he lived in early 5th century CE in the city of Ujjain, located roughly at the center of the Indian peninsula.

Abhijnanasakuntala (The Recognition of Shakuntala), is based on an episode taken from the great Indian epic, the Mahabharata. Kālidāsa retains the basic plot line of the episode but alters it in key ways to adapt it to the stage and make it more romantic. The story revolves around a beautiful maiden named Shakuntala who is the daughter of an ascetic sage and a heavenly nymph. Abandoned by her parents, she was raised in the hermitage of another sage who found her in the care of a flock of “shakunta” birds. Hence, he named her Shakuntala, i.e., protected by shakunta birds. One day, she falls in love with a visiting king named Dushyant who gives her a ring as the token of their love and promises to return to take her with him. In his absence Shakuntala gives birth to a son. Due to a curse, he forgets about her and only recalls her when he encounters the ring again after many years. Their son, Bharata, goes on to become the first emperor of India whose descendants are the protagonists of the Mahabharata.

Of all his works, Kālidāsa’s Abhijnanasakuntala became the most world-renowned after it was translated into English by Sir William Jones in Calcutta in 1789. Translations in German and French appeared subsequently. The play was to be translated into all these languages, and many more, numerous times by prominent linguists and indologists of the 19th and 20th centuries. Among these is the translation featured here by the famous indologist Sir Monier Monier-Williams.

Scholarly interest in Sanskrit in European and American academia is not only due to the language’s own rich literary tradition but also because it is the sacred language of the Hindu, Buddhist and Jain religious traditions. Even though the Buddhist and Jain traditions initially used other languages they eventually switched to Sanskrit, as it was the language of high culture, philosophy, and scholarly discourse in ancient India. The linguistic influence of Sanskrit on local South Asian languages is comparable to Latin and ancient Greek in Europe.

Vedic Sanskrit, an ancient form of Sanskrit in which the Vedas, the most ancient Hindu scriptures, are composed, is an important source for the study of the evolution of Indo-European languages. In fact, having been orally composed between 1500 and 1200 BCE, the Vedas are among the oldest literary creations in any Indo-European language.

The study and teaching of Sanskrit at UC Berkeley goes back to the 1890s and includes an impressive list of world renowned scholars and interest in Kālidāsa has also been keenly pursued here. Among others, Professor Arthur W. Ryder, Professor of Sanskrit, published a translation of a selection of Kālidāsa’s works in 1912 that included Abhijñānaśākuntala. This translation became the basis for a performance of the play in the Greek Theater in 1914. The play continues to be widely performed into the present day. Today, Professor Robert P. Goldman is UC Berkeley’s Magistretti Distinguished Professor of Sanskrit. He is also the director, general editor, and principal translator of the recently published multi-volume critical edition of a fully annotated English translation of Valmiki’s famous epic, Ramayana, and has received many awards and fellowships.

Contribution by Adnan Malik

Curator and Cataloger for the South Asia Collection

South/Southeast Asia Library

Special thanks to Sally Sutherland Goldman, Senior Lecturer in Sanskrit

Department of South and Southeast Asian Studies

Title: Śakuntalā, a Sanskrit drama, in seven acts. The Deva-Nāgari recension of the text, ed. with literal English translations of all the metrical passages, schemes of the metres and notes, critical and explanatory by Monier Williams.

Authors: Kālidāsa

Imprint: Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1876.

Edition: 2nd

Language: Sanskrit

Language Family: Indo-European, Indo-Aryan

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (UC Berkeley)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/002751897

Other online editions:

- Translations of Shakuntala and Other Works by Kālidāsa (Internet Archive)

- Monier-Williams translation and Sanskrit text (2nd ed.) (Internet Archive)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Śakuntalā, a Sanskrit drama, in seven acts. The Deva-Nāgari recension of the text, ed. Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1876.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Ancient Egyptian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

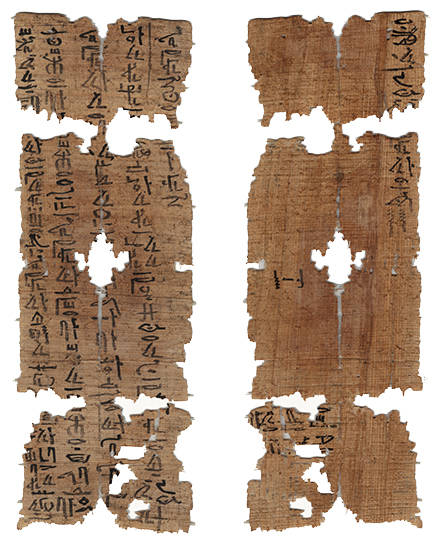

Ancient Egyptian is a language that was spoken in and around the Nile River valley from the 4th millennium BCE through the 11th century CE. The earliest form of this language was written in the Hieroglyphic script. Soon after the development of Hieroglyphs, the availability of papyrus as a light, portable writing material and the complexity of drawing complete Hieroglyphic signs led to the development of Hieratic. This cursive form of the ancient Egyptian script is what an individual named Heni used to write a letter to his deceased father, Meru, sometime between 2160 and 2025 BCE. Heni’s composition is one of a handful of texts known as “Letters to the Dead,” which have been found throughout Egypt written on materials as diverse as pottery, figurines, linen, and stone stelae. Although this genre of text is attested for a period of nearly two thousand years, only a handful of examples survive, all of which share the common goal of communicating a wish or desire from the living to the dead.

The letter of Heni, written in vertical columns, as was typical for Hieratic of this time period, opens with a greeting to Meru before imploring him to intercede on his son’s behalf and offer aid. Heni believes he is being falsely accused of harming someone, insisting the wrong was instigated by other parties. Unfortunately, the details of the event are lacking. These letters are frustratingly vague, as it was assumed that the intended audience — usually a close relative or acquaintance — knew the specifics of the situation. The letter was folded and addressed like letters sent among the living. That is to say, the address was written on the outside (the two short lines written horizontally towards the bottom of the verso of the papyrus): the nobleman (iry-pat), count (haty-a), overseer of priests, Meru. In order to ensure the message was delivered, Heni deposited the small papyrus in his father’s tomb. Whether or not his father (or the living judges) recognized his plea of innocence, we will never know.

Several millennia later, Heni’s papyrus was found during the archaeological excavations of George A. Reisner. Working under the patronage of Phoebe A. Hearst, Reisner excavated the site of Naga ed-Deir between 1901 and 1904. The letter was found in the tomb of Meru (N.3737), which was decorated with images of him enjoying everyday life. The papyrus was shipped by Reisner to Germany for conservation, where it remained until after World War II. When financial difficulties compelled Phoebe Hearst to withdraw funding for the Berkeley Egyptian Excavations in 1905, George A. Reisner was appointed to the faculty at Harvard University and to the curatorial board at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston. A young, enterprising curator at the MFA, William Kelly Simpson, knew of papyri excavated by Reisner and later sought them out in Germany. With Simpson’s help, the papyrus — along with several others — traveled from West Berlin to the MFA. After securing them in Boston, Simpson published the first translation of this text. Despite earlier inquiries from faculty at UC Berkeley, it was not until the 2000s that Professor Donald Mastronarde of the Berkeley Department of Classics ascertained the whereabouts of these papyri and engineered their return to Berkeley. The Letter to the Dead, along with numerous other ancient Egyptian papyri, are now housed in the Center for the Tebtunis Papyri at The Bancroft Library, as part of the Egyptian collections acquired by Phoebe A. Hearst between 1899 and 1905.

Courses in Ancient Egyptian are taught at UC Berkeley in the Department of Near Eastern Studies as part of a program in Egyptology. Students can take classes in several phases of the language, including Old, Middle, and Late Egyptian, and Demotic.

Emily Cole, Postdoctoral Scholar

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, The Bancroft Library

Source consulted:

Simpson, William Kelly. “The Letter to the Dead from the Tomb of Meru (N 3737) at Nag’ Ed-Deir.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, vol. 52, 1966, pp. 39–52. JSTOR.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Letter to the Dead

Author: Heni

Registration Number: Papyrus Hearst 1282

Imprint: 9th or 10th Egyptian Dynasty. First Intermediate Period (Between 2160 and 2025 BCE)

Language: Ancient Egyptian

Language Family: Afro-Asiatic, Semitic

Source: The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, The Bancroft Library (UC Berkeley)

URL: http://dpg.lib.berkeley.edu/webdb/apis/apis2?invno=P%2eHearst%2e1282&sort=Author_Title&item=1

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Latin

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

The “golden age” of Latin comprises works produced between the first century BCE and the first century CE. The canon of Latin literature includes the works of such authors as Caesar, Cicero, Vergil, Horace, Livy, and Ovid, which frequently make up the core curriculum of any Classics department today.[1] Linguistically speaking, the Latin language became a predominantly literary and administrative language, learned by elite members of society who had an educational or professional need for it.[2] This does not mean that Latin was not spoken anymore, it just means that it ceased being anyone’s first language, and that, eventually, educated inhabitants of the broader Roman empire were bilingual, fluent in both Latin and in their own dialects (which became the Romance languages). The adoption of Latin as the unifying administrative language of the Roman empire — and later as the unifying administrative and liturgical language of the Roman Catholic Church — ensured Latin’s place as a global language through the 18th century.

The most influential ancient Roman author was Marcus Tullius Cicero. When students read Cicero today, they are likely to be assigned his famous speeches, such as the Catiline Orations or the Pro Caelio; one of his philosophical treatises, such as De re publica; or even his letters. What students may not know is that it was one of Cicero’s so-called juvenile works, written before he was 21 years old, that had the most outsized impact on the history of education in the West. Cicero wrote De inventione when he was studying rhetoric as a young man. The title topic “invention” (meaning “discovery”) refers to the first, and most important, task of the orator, which is to develop effective arguments that will persuade a judge. Because De inventione was written as a series of notes, it was easily adaptable to the classroom as a handbook for teaching rhetoric. De Inventione became such a foundational text in the medieval and Renaissance classroom that 322 complete manuscripts survive today.[3] As a result, Ciceronian rhetoric thoroughly permeated medieval and Renaissance intellectual culture and greatly influenced the literature, historiography and political theory of those periods, the fruits of which students continue to learn in humanities courses today.[4]

That Renaissance artists and architects looked to ancient sculptures, paintings, and architecture to inform their designs is well known. Renaissance Latin authors similarly looked to Classical authors as models for writing the “best Latin.” These humanists, as they are called, were reacting against what they saw as idiosyncratic Latin that evolved from the 11th to the 13th centuries to accommodate the highly technical and abstract concepts of theology and philosophy, and they desired a return to what they deemed the best models from antiquity: Cicero for prose and Vergil for poetry.[5] The Italian humanists Pietro Bembo and Jacopo Sadoleto of Italy, and the Belgian humanist Christophe de Longueil, went so far as to declare Cicero the only model for good Latin. The eclectic thinker and scholar Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466-1536) found this idea so ridiculous — because slavish imitation of a single model does not account for individual ability or changing times — that he penned a satirical dialogue titled Ciceronianus that mocked this idea of a single model. In his satire, the character Nosoponus is paralyzed by writer’s block, afraid to write a single word that is not found in Cicero; while Bulephorus endeavors to convince Nosoponus to seek out a greater array of authors as models and to internalize what he learns in order to develop his own style.[6] These arguments for some stylistic flexibility aside, the Renaissance marked the period during which the Latin language became well and truly fixed; by this time, the national vernacular languages had come into their own and Latin had become the domain of an elite educational curriculum.[7] The advantage to us of this fixing is that Latinists today are able to read, with relative ease, a wealth of texts that span more than a millennium.

The study of Latin has many applications and is an important tool for research and study in a variety of fields. Besides Classics, Berkeley students use Latin in courses within the department of Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology,[8] as well as PhD programs in Medieval Studies,[9] Romance Languages and Literatures,[10] and Renaissance and Early Modern Studies.[11]

Contribution by Jennifer Nelson

Reference Librarian, The Robbins Collection, UC Berkeley School of Law

Notes:

- Department of Classics, UC Berkeley

- Leonhardt 2013: 56-74.

- Two examples of manuscripts of De inventione are in the British Library (Arundel MS 348) and in the Kongelige Bibliotek in Denmark (GKS 1998 4°)

- Ward 2013: 167. (accessed 6/24/19)

- The notion that medieval Latin was fundamentally different from Classical Latin was a humanist construct. While, in some cases, there did exist identifiable regional flavors, evidence of certain non-“standard” constructions, or writing conventions developed for specific genres (frequently in the technocratic, bureaucratic, or legal realms), in general Latin did not change in any fundamental way in the period known as the Middle Ages.

- Nosoponus means “suffering from illness”; Bulephorus means “one who gives counsel.”

- Leonhardt 2013: 184-219.

- Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology (AHMA), UC Berkeley

- Program in Medieval Studies Program, UC Berkeley

- Romance Languages and Literatures, UC Berkeley

- Designated Emphasis in Renaissance and Early Modern Studies (REMS), UC Berkeley

Sources consulted:

- Erasmus, Desiderius. Dialogus cui titulus Ciceronianus, sive De optimo genere dicendi (Ciceronianus, or, A Dialogue on the Best Style of Speaking). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1976.

- Hubbell, H. M. Introduction to Cicero’s De inventione (On Invention), with an English translation by H. M. Hubbell. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1968, xi-xviii.

- Leonhardt, Jürgen (trans. Kenneth Kronenberg). Latin: Story of a World Language. Cambridge, Massachusetts : The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013.

- Ward, John O. “Ciceronian Rhetoric and Oratory from St. Augustine to Guarino da Verona.” In van Deusen, Nancy, Cicero Refused to Die: Ciceronian Influence Through the Centuries. Leiden: Brill, 2013, 163-196.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: De inventione ; De optimo genere oratorum ; Topica, with an English translation by H. M. Hubbell

Title in English: On Invention (and other works)

Author: Marcus Tullius Cicero

Imprint: Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1949.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Latin

Language Family: Indo-European, Italic

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Michigan)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/api/volumes/oclc/685652.html

Other online editions:

- Erasmus, Desiderius. Dialogus cui titulus Ciceronianus, sive De optimo genere dicendi (Ciceronianus, or, A Dialogue on the Best Style of Speaking). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1949.

Loeb Classical Library (UCB only), DOI: 10.4159/DLCL.marcus_tullius_cicero-de_inventione.1949

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Mongolian Cyrillic (Khalkha)

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

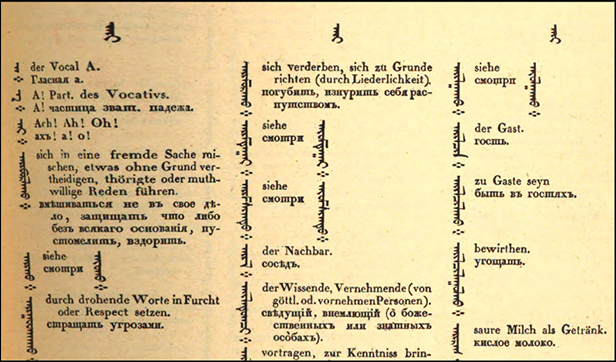

The expansion of the Russian Empire’s frontiers toward Manchu China meant interactions with several different Mongolic language groups that inhabit Siberia and the Far East, including Buryat and Oirat variants. The official Khalka dialect is prominent in the Republic of Mongolia. The 19th-century digitized book presented here is one of the earliest dictionaries of Mongolian language that was published by the Imperial Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg. We are highlighting this specific dictionary in consultation with the faculty members that teach and conduct their research in Mongolian. The scripts of the Mongolian language have evolved over the long history of the Mongols. Due to the Sovietization of Outer Mongolia, the alphabet was changed to Cyrillic characters (Khalkha) while the Inner Mongolia of the People’s Republic of China continued to use a variant of the traditional script which is called Uyghur-Mongolian.

Several UCB faculty members focus their research on Mongolia. Among them is Professor Emerita Patricia Berger, an art historian, and Professor Jacob Dalton, who is a world known specialist on Tibetan Buddhism. Tibetan Buddhism’s history and practice are syncretic to both past and present practice to the Buddhism of Mongolia. Brian Baumann is a lecturer of Mongolian language in East Asian Languages and Cultures and is instrumental in teaching language courses. Professor Sanjyot Mehendale, who teaches courses on Central Asia and the Silk Roads in the Department of Near Eastern Studies, is an archaeologist specializing in Eurasian trade and cultural exchange of the early Common Era. She has worked on several archaeology sites and projects in Central Asia, including Samarkand and Afghanistan.

The Mongolia collection has been developed to reconnect students with the history of Mongolia and the surrounding region. Besides students, the collection development revolves around the needs of faculty members and other scholars at UC Berkeley. Mongolia’s ethnic composition represents a unique tapestry of the Central Asian nationalities living within the geographic boundaries of the region along with the Mongols. The Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures offers courses related to Mongolia which vary from elementary Mongolian to Mongolian Buddhist Ritual (Buddhist Studies 190).[1] While the collection of Mongolian language books from the Republic of Mongolia printed in Cyrillic is approximately 1800 titles, Doe Library acquired nearly 800 new titles from 2009 through 2019. Besides, Mongolian language materials, we also have an extensive collection of books in Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Tajik, Turkmen and Uzbek languages.

As a librarian for East European and Central Asian Studies, I focused initially on collecting materials related to Buryat Mongols of Siberia. With a generous gift from the government of Mongolia, UC Berkeley and the Institute of East Asian Studies were delighted to announce the establishment of the Mongolia Initiative. This initiative led to the beginning of the teaching of Mongolian on campus for the first time in many years. Thus, the need for the collections of materials in Mongolian from the Republic of Mongolia became an ever-pressing reality. Since 2015, UC Berkeley has also received funding from the U.S. Department of Education to begin teaching elementary Mongolian. This National Resource Center grant recognizes UC Berkeley as a national leader for teaching and research on East Asia, including Mongolia.[2] It funds the education of lesser-taught world languages, in particular Mongolian, which is one of the critical languages for the national security of the United States government.[3]

Contribution by Liladhar Pendse

Librarian for the Mongolian Collections, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Mongolian (MONGLN) Berkeley Academic Guide – UCB (accessed 6/24/19)

- About the Mongolia Initiative, UC Berkeley (accessed 6/24/19)

- Languages of Interest, Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) (accessed 6/24/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Mongolisch-deutsch-russisches Wörterbuch : Nebst Einem Deutschen Und Einem Russischen Wortregister =: Mongolʹsko-ni︠e︡met︠s︡ko-rossīĭskīĭ Slovar : S Prisovokuplenīem Ni︠e︡met︠s︡kago I Russkago Alfavitnykh Spiskov.

Title in English: Mongolian-German-Russian Dictionary: In addition to a German and a Russian word index.

Author: Schmidt, Isaak Jakob, 1779-1847.

Imprint: Sanktpeterburg: Kaiserliche Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1835.

Edition: 1st.

Language: Mongolian Cyrillic (Khalkha)

Language Family: Mongolic

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (UCLA)

URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.d0006851489

Other online editions:

- Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (BSB)

http://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10691089-1

Print editions at Berkeley:

- Schmidt, Isaak J. Mongolisch-deutsch-russisches Wörterbuch: Nebst Einem Deutschen Und Einem Rusischen Wortregister. St. Petersburg: Bei den commissionairen der Kaiserlichen akademie der wissenschaften, W. Graeff und Glasunow, 1835.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Mongolian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

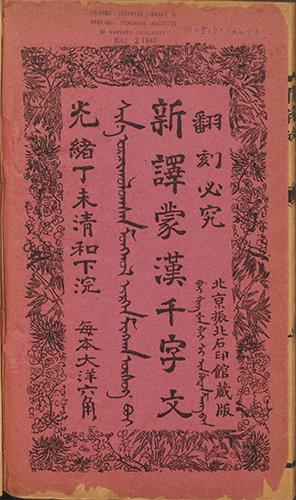

The Thousand Character Classic (Chinese: 千字文), also known as the Thousand Character Text, is one of the earliest and most widespread basic literacy texts for the study of classical Chinese. The rhyming text was composed by learned and talented scholar Zhou Xingsi of the Southern Liang dynasty (502-557) and has been used ever since as a primer for teaching Chinese characters to children. It contains exactly one thousand non-redundant characters arranged into 250 four-character couplets. Not only is the form succinct and poetic, but the text also imparts traditional Chinese knowledge and wisdom. It was widely circulated in ancient Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. It has also been translated into several western languages, including English, Latin, German, Italian, and French. The New Mongolian Translation of the Thousand Character Classic contains traditional Uyghur-Mongolian and Chinese text, as well as Manchu phonetic transcription. It is valuable for the study of Mongolian and Manchu phonology. The C.V. Starr East Asian Library owns a facsimile of the 1907 stone print edition. The original edition is held by the Harvard-Yenching Library and was recently digitized.

The course description for Mongolian 1A follows: “Mongolian is the language of a people who politically have emerged on the world stage after verily hundreds of years of imposed isolation, who geographically live on the vast open steppe that ranges from the Gobi to Siberia, who economically juggle an ancient tradition of pastoral nomadism with the development of national and private industry, who culturally know an eclectic, vibrant cosmopolitanism belied by their rugged open spaces, and who long ago established the largest contiguous empire the world has ever known.”[1] UC Berkeley has a long tradition of Mongolian Studies reaching back to the early 20th century. In 1935, Ferdinand Lessing, a German scholar of Central Asia, was named the fourth Agassiz Professor of East Asian Studies and established this country’s first course in the Mongolian language, as well as courses on Mongolia’s Buddhist tradition. He also published the first scholarly Mongolian-English dictionary in 1960.[2] Mongolian studies continued to advance under the direction of Professor James Bosson, who taught at Berkeley from 1964 through 1996. He was also a renowned scholar for the Manchu and Tibetan languages. Students at Berkeley begin with Khalkha Mongolian, the standard language of Mongolia, in its context as a dialect of Mongolian language proper using Cyrillic script and introducing traditional script. They then advance to Literary Mongolian, its phonetics, grammar, vertical writing system and its relation to living spoken language.

With a generous gift from the government of Mongolia, UC Berkeley and the Institute of East Asian Studies launched the Mongolia Initiative in 2016. Mongolian is now being taught on campus for the first time in many years by Professor Brian Baumann who concentrates on Mongolian texts on Buddhism, history and culture. Funding from the U.S. Department of Education has also supported the language program and other research activities on Mongoliat as well as for enrichment of the Mongolian collection in the Library.

Contribution by Jianye He

Librarian for the Chinese Collections, C.V. Starr East Asian Library

Sources consulted

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: 新譯蒙漢千字文 = Sin-e orčiγuluγsan mongγol irgen mingγan üsüg bui

Title in English: The New Mongolian Translation of the Thousand Character Classic

Author: Zhou, Xingsi, d. 521.

Imprint: Beijing : Zhen bei shi yin guan, Guangxu ding wei, 1907.

Edition: n/a

Language: Mongolian

Language Family: Mongolic

Source: Harvard College Library Harvard-Yenching Library

URL: http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:FHCL:10443432

Print editions at Berkeley:

- Facsimile reprint has been published in volume one of 清代蒙古文啓蒙讀物薈萃 = Qing dai Menggu wen qi meng du wu hui cui. Huhehaote Shi : Yuan fang chu ban she, 2016.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)