Tag: BL South Asia

Telugu

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Telugu is a Dravidian language that is spoken in southern Indian, and is the official language of the Indian states of Andhrapradesh and Telangana. With more than 75 million native speakers, it has an epigraphical presence going back to the 6th century CE and a literary tradition that began in the 11th century.

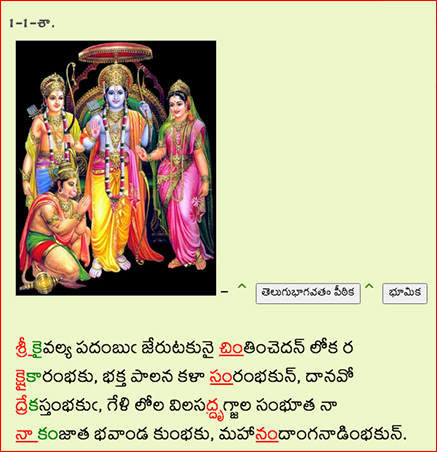

Telugu’s literary tradition began with the translation of Sanskrit sacred and literary texts. Over the centuries, however, the language developed its own literary forms and canon. One text that was a translation from Sanskrit but went on to have a profound impact on Telugu’s literary heritage was Pōtana’s (also spelled, Pōthana) translation of the Bhāgavatapurāṇa called Śrīmahābhāgavatamu. The Bhāgavatapurāṇa is a major scripture of the Vaishnava tradition of Hinduism that describes the incarnations of the god Vishnu, especially as Krishna, and also explains the tradition’s cosmological, theological, and soteriological beliefs. Needless to say, the Bhāgavatapurāṇa is the focus of intense study and devotion among Vaishnavas, and Pōtana’s translation continues to be so for Telugu speakers.

Pōtana lived in the latter half of the 15th century. He is traditionally believed to have been born to a Niyogi Brahamin family living in a village called Bammera in the Jangaon district of present day Telangana. He was a naturally gifted poet, and earned his living as a farmer. A devout and religious man, he was inspired to translate the Bhāgavatapurāṇa after a religious experience.

Pōtana’s poetic style with its rhythmic use of alliteration and his devotion-steeped emotions have ensured a lasting fame for his Śrīmahābhāgavatamu. Pōtana’s literary devotional offering continues to inspire reverence among Telugu-speaking devotees of Lord Krishna. In addition, experts on Telugu literature continue to appreciate the linguistic and literary merits of his work while even illiterate people are familiar enough with it to quote its verses when discussing spiritual and ethical matters.

Telugu has been taught at Berkeley for several decades, currently Ms. Bharathy Sankara Rajulu holds a joint appointment as Lecturer in Tamil and Telugu in the Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies.

Contribution by Adnan Malik

Curator and Cataloger for the South Asia Collection

South/Southeast Asia Library

Title: Bhāgavatapurāṇa

Title in English: Bhagavatapurana

Author: Pōtana, active 15th century.

Imprint: latter half of 15th century

Language: Telugu

Language Family: Dravidian

Source: www.telugubhagavatam.org

URL: http://telugubhagavatam.org/?tebha&Skanda=1&Ghatta=1

Other online editions:

- Dasama Skandha of Pōtana’s Bhāgavata Purāna: A Literal Translation into English (Part I) by T. S. B. Narasaraju (accessed 8/11/20)

- Dasama Skandha of Pōtana’s Bhāgavata Purāna: A Literal Translation into English (Part II) by T. S. B. Narasaraju (accessed 8/11/20)

- Excerpts From Potanas Bhagavatam by A.V.S. Sarma. Tirupati: Tirumala-Tirupati Devasthanams, 1957. Internet Archive (Digital Library of India)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Mahākavi Bammera Pōtanāmātya praṇīta Śrī Mahābhāgavatamu. Haidarābād: Pōṭṭi Śrīrāmulu Telugu Viśvavidyālayaṃ, 2006.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Panjabi

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Panjabi (also written Punjabi) is an Indo-Aryan language with about 125 million speakers in South Asia and beyond. With most Panjabi speakers living in the Pakistani province of Panjab and the neighboring Indian state of the same name, it also has a large diaspora of speakers all over South Asia and beyond, especially in Great Britain and Canada. Panjabi is written in the Arabic script in Pakistan and in the Gurmukhi script in India.

With beginnings in the 13th century, one striking feature of Panjabi literature is the large number of ballads of unrequited love. Of these, few have been as popular as the love story of Hir and Ranjha, often just referred to as Hir (pronounced as Heer), whose tragic love story was given poetic form by a number of poets through the centuries.

Dhaidu Ranjha was the youngest and handsomest of eight brothers and two sisters. He was the spoilt darling of his parents which made his older brothers jealous. On the death of the parents the brothers divided up the farmland among themselves giving Ranjha the worst fields. Matters were made worse by the hostility of Ranjha’s sisters-in-law, who were fed up with the young women of the village swooning over their good-for-nothing brother-in-law. During an argument over food one day they insulted and taunted him and dared him to marry Hir, the beautiful daughter of the powerful Sial clan, if he had such a high opinion of himself.

Ranjha left his house in a huff vowing never to return and traveled all day until he was dead tired. He came across a throne in a beautiful garden and stretched himself on it and went to sleep. He was soon awakened by an indignant but radiantly beautiful young woman and her pretty companions. This was none other than Hir who angrily wanted to know why this stranger was sleeping on her throne in her private garden. However, when a few words were exchanged it was love at first sight for both of them. Ranjha decided to become a herdsman of Hir’s family’s water buffaloes in order to stay near her.

Hir’s family soon found out about their secret meetings and decided to marry her off into the Khera family that belonged to another powerful clan of the region. Hir and Ranjha were devastated and Ranjha, having decided to renounce the world, went to the monastery of Bal Nath, a master of the Nath sect of yogis and became a disciple. He began wandering as a mendicant only one day to knock on the door of Hir’s in-laws. The lovers resumed their secret trysts only to be found out again. This time the scandal was even bigger and more dangerous as the honor of two powerful clans was involved. Nevertheless, Hir’s family reluctantly agreed to allow Hir and Ranjha to marry. However Kaido, Hir’s maternal uncle could not bear the dishonor brought to the family, and on the day of the wedding killed Hir by making her eat a poisoned confection. When Ranjha came to the house and saw what had happened he immediately ate the rest of the poisoned confection at last uniting with his beloved in death if not in life.

The earliest extant version of Hir was composed by the poet Damodar (1486-1568) in the early 16th century. Other versions were produced by various poets over the centuries yet few reached the fame and popularity of Waris Shah’s version which continues to be sung and enjoyed to this day.

Born in 1722 in the town of Jandiala Sher Khan in present-day Pakistan, Waris Shah (also spelled Vāris̲ Shāh and Warisa Shaha) became the disciple of Hafiz Ghulam Murtaza, a Qadiri-Chisti Sufi master from the city of Qasur. After completing his education, Waris Shah settled in the village of Malka Hans, where according to tradition in 1766 Waris Shah wrote his version of Hir after his own experience of unrequited love. The beautiful language and refined sentiments of Waris Shah’s Hir made it an instant success, especially among Sufi and other religious circles who saw it as an allegory of the mystical path of spiritual realization and the soul’s yearning for union with the divine. One interesting feature of Waris Shah’s Hir is a detailed and appreciative description of the spiritual traditions of the Nath yogis highlighting the ecumenical vision of Waris Shah and his belief in the universality of love and its spiritual grace. It was for this reason that during the Partition riots of 1947 when the famous contemporary poet Amrita Preetam left her hometown of Lahore on a train heading to Delhi, she composed a poem of lament addressed to Waris Shah asking him to look at his strife-torn Panjab and open another page of the book of love.

As for Hir and Ranjha, while historians may doubt their existence the tomb in which both are reputedly buried continues to be a destination for star-crossed lovers, Sufi and other spiritual aspirants, and all those drawn to the grace of love.

UC Berkeley has offered instruction in Panjabi since the 1980s where introductory and intermediate Panjabi is taught in the Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies. The current Panjabi instructor is Ms. Upkar Ubhi who has been teaching Panjabi on campus since 1998.

Contribution by Adnan Malik

Curator and Cataloger for the South Asia Collection

South/Southeast Asia Library

Title: Hir Ranjha

Title in English: The Adventures of Hir and Ranjha

Author: Vāris̲ Shāh, 1722–1798.

Imprint: n/a

Edition: n/a

Language: Panjabi

Language Family: Indo-European, Indo-Aryan

Source: Punjabi Kavita

URL: https://www.punjabi-kavita.com/Waris-Shah.php

Other online editions:

- The Adventures of Hir and Ranjha translated in to English by Charles Frederick Usborne, 1874 – 1919. (University of Heidelberg)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Hīra / Wārasashāha. Ammritasara: Bhāī Catara Siṅgha Jīwana Siṅgha, [19–]. In Panjabi (Gurmukhi script).

- Hīr Vāris̲ Shāh / Faqīr Muḥammad Faqīr; mushkil lafẓāṉ da tarjamah, Sult̤ān Khārvī. Lāhaur: Taḵẖlīqāt, 2012. In Panjabi (Arabic script).

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Bengali

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

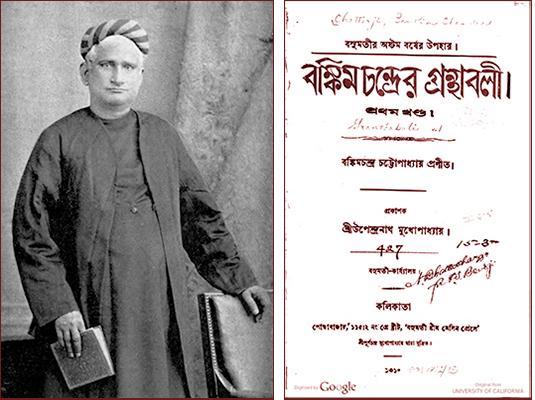

Bankimacandra Cattopadhyaya (1838-1894) was not only the very first novelist of the Bengali language but is also considered one of its greatest. He wrote the first novel in Bengali as well as the first novel in English by an Indian. His works are still avidly read and a poem in his historical novel Anandamatha titled “Vande Matram” (“Hail Mother”) so inspired Indian freedom fighters it was officially adopted as India’s national song (not the same as the national anthem which is a poem by Tagore).

Bankim was born in a Brahim family, and grew up in the town of Midnapur where his father worked for the colonial government. After his education Bankim followed his father into civil service while at the same time pursuing a successful literary career. Starting with poetry he turned towards writing novels. His first published novel, Rajmohan’s Wife, was composed in English. However, he soon turned to Bengali and in 1865 published the very first novel in the language called, Durgesanandini (“Daughter of the Lord of the Fort”). He continued to write novels as well as satirical and humorous sketches. A commentary he wrote on the Gita was published posthumously.

Outside Bengal, his historical novel Anandamatha (“The Monastery of Bliss”), published in 1882, became the most famous and somewhat controversial for its attitude towards Muslims. It is set during the Fakir Rebellion of the late 18th century when Bengalis rose up against the oppressive rule of the East India Company during a famine. As mentioned above, it contains an ode to the motherland conceived as a goddess titled “Vande Matram” that became very popular with Indian freedom fighters during the struggle for independence. Bankim’s political stances got him in trouble with British authorities in his own lifetime, but in 1894—the same year he died—Queen Victoria made him a Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire.

Bankim belonged to a generation of Bengalis who had grown up under British rule and were able to reflect on the massive changes that rule had brought. The generation immediately before his had been the first to be exposed to western and modern ideas, and many of them accepted them with enthusiasm while others did so reluctantly. While Bankim did not question the adoption of western and modern ideas and technologies, he and members of his generation were more familiar with them and were in a position to critically judge the promises the British had made to Indians about the benefits of European rule and civilization. At the same time they had gained the confidence to appreciate aspects of their Indian and Hindu heritage which they wanted to hold onto as they modernized. Apart from their literary merits, these are some of the themes that make Bankim’s works relevant to this day.

Bengali, or Bangla to its nearly 230 million speakers, is an Indo-Aryan language belonging to the Indo-European family of languages. It is the official and predominant language of Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal, and also has many speakers in the neighboring Indian states of Tripura and Assam. With a rich and centuries old literary tradition it continues to be a major language of modern South Asia. At UC Berkeley, introductory and intermediate Bengali is taught through the Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies.

Contribution by Adnan Malik

Curator and Cataloger for the South Asia Collection

South/Southeast Asia Library

Title: Granthabali

Title in English: Collected Works

Authors: Caṭṭopādhyāẏa, Baṅkimacandra, 1838-1894.

Imprint: Kalikata : Upendra Nath Mukhopadhyaya, Basu Mati Office, 1310-11 [1892/93-93/94].

Edition: 1st

Language: Bengali

Language Family: Indo-European, Indo-Aryan

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (UC Berkeley)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100787603

Other online editions:

- Bankim Rachanabali (volume 1 of complete works in Bengali), Internet Archive (Digital Library of India)

- The Abbey Of Bliss (English translation of Anandamath), Internet Archive (British Library)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Granthabali. Kalikata : Upendra Nath Mukhopadhyaya, Basu Mati Office, 1310-11 [1892/93-93/94].

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

ucblib.link/languages

Hindi

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

The two great Indian epics, the Mahābhārata and the Ramayana, dominate South Asian cultures in ways that few other literary productions do. Both epics have to do with the heroic exploits of the human incarnation of the Hindu deity Vishnu, one of the most widely worshipped gods of the Hindu pantheon. The Ramayana deals with the story of King Ramachandra, the seventh incarnation of Vishnu, who came down to Earth to establish just rule and a harmonious society.

King Rama is not only the ideal monarch and warrior but also embodies the virtues of justice, wisdom, patience, and perseverance. He is an obedient son, a generous brother, and a caring husband. His rule became synonymous with justice and good governance so that throughout the centuries the expression rama rajya (Rama’s rule) has been used to describe the ideal government.

The most famous version of the Ramayana is the Sanskrit composition of Valmiki known as Valmiki’s Ramayana. It has the status of a sacred text and is highly revered. It is also a masterpiece of Sanskrit literature. There were many versions of the Ramayana composed subsequently, both in Sanskrit and other languages. Some became more popular than others, but one is justified to say that after Valmiki’s Ramayana, the version that is most famous is the Ramacaritamanasa created in the Awadhi dialect of Hindi by Tulasidasa in the 16th century. In fact, Tulasidasa’s Ramayana quickly garnered wide popularity and its recitation became part of the worship service of many sects and religious traditions of Vaishnava Hinduism, especially after the introduction of the printing press in the early 19th century. Its communal recital, often set to a distinctive tune, continues to this day. Tulasidasa was himself an ardent devotee of Lord Rama and in expressing his love and reverence for the divine incarnation in beautiful poetry he managed to create one of the greatest poetic works of Hindi literature.

Tulasidasa was born in the region of Avadh in what is now eastern Uttar Pradesh in modern India. There is disagreement about his date of birth, but scholars generally consider it to be around 1532 CE. Traditional accounts state that he was a Brahmin by caste and was initiated into a mystic and ascetic lineage devoted to the loving worship of God through the incarnation of Rama. He is supposed to have spent time as a student with various sages and teachers in Banaras where he learnt the classical Sanskrit texts as well as Vaishnava scriptures. He decided to compose a Ramayana in Awadhi for the edification of the general population, and thus, composed the Ramacaritamanasa, The Lake of the Deeds of Rama. He composed a number of other works as well but the Ramacaritamanasa remained his magnum opus. He died in 1623 in Banaras.

When he set about composing the Ramacaritamanasa, Tulasidasa had a long tradition of composing Ramayanas to look up to going all the way back to Valmiki. At the same time, he was well aware of the literary styles and compositions of his own time when the beginnings of Hindi literature had already been made and a corpus and canon were slowly but steadily evolving. Tulasidasa was to leave his mark on this evolution.

Tulasidasa followed the conventions of chanda prosody that had been the hallmark of Sanskrit poetry and was also followed in other languages, especially for works in Aparbhramsa, the medium of literary production before the rise of Hindi. He also might have been inspired by the metrical structure of the premakhya, a genre of love ballads popular in his days, in creating the basic form for the Ramacaritamanasa. The work is composed in regular arrangements of caupais (quatrains) and dohas (couplets) and he used a different meter for every section of the work.

Tulasidasa used his considerable literary skills to retell the story of the struggles and ordeals of Lord Rama, his brother Lakshmana, his wife Sita, and his devoted disciple, the monkey god, Hanumana, as they faced family feuds, exile, and an epic war against the demon king, Ravana, who had kidnapped Sita, until they returned victorious and vindicated to their capital, Ayodhya, to establish a just and prosperous kingdom.

Ramacaritamanasa is not just a skilled literary retelling of the ancient epic in the charming Awadhi dialect but is redolent with Tulasidasa’s own loving devotion to Lord Rama which seeps through its every line. Perhaps that is why millions of devotees of Lord Rama continue to use it to express their own love and devotion in prayer.

Hindi has been taught UC Berkeley since the late 1960s. Currently, there are two Hindi lecturers. Usha Jain has authored books on Hindi language instruction, including Introductin to Hindi Grammar (1995), Intermediate Hindi Reader (1999), and, Advanced Hindi Grammar (2007). The other instructor is Dr. Nora Melnikova whose interests include second language teaching, modern Theravada Buddhism, and the Early Modern languages and literature of North India. She has also translated Mirabai’s medieval Hindi poems and Erich Frauwallner’s History of Indian Philosophy into Czech.

Contribution by Adnan Malik

Curator and Cataloger for the South Asia Collection

South/Southeast Asia Library

Title: Rāmacaritamānasa

Title in English: The Rámáyana of Tulsi Dás

Authors: Tulasīdāsa, 1532-1623.

Imprint: Allahabad : North-western Provinces Government Press, 1877.

Edition: Indo-European, Indo-Aryan

Language: Hindi

Language Family: Indo-European, Indo-Iranian

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (UC Berkeley)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006125797

Other online editions:

- Recitation of text on YouTube (accessed 11/19/19)

- The Rámáyana of Tulsi Dás. Rev. and illustrated. Allahabad : North-western Provinces Government Press, 1883. (Internet Archive)

- The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki : An Epic of Ancient India / introduction and English translation by Robert P. Goldman ; annotation by Robert Goldman and Sally J. Sutherland. Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, ©1984- ©2017. (Project Muse – UCB only)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- The Rámáyana of Tulsi Dás. Allahabad : North-western Provinces Government Press, 1877.

- The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki : An Epic of Ancient India / introduction and English translation by Robert P. Goldman ; annotation by Robert Goldman and Sally J. Sutherland. Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, ©1984- ©2017.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Urdu

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

The dastan is a genre of oral and prose narrative that initially developed in Persian but then spread to other languages influenced by the Persian literary tradition. To be sure, oral tale-telling is hardly unique to Persian or Persian-influenced languages, but the dastan has some unique literary features that make it stand out. Dastans often have very long story lines that can be embellished and stretched even further through detailed descriptions of characters, events, and locations. With their dramatic narratives, dastans are primarily meant for oral performances and enjoying the richness of language and literary traditions.

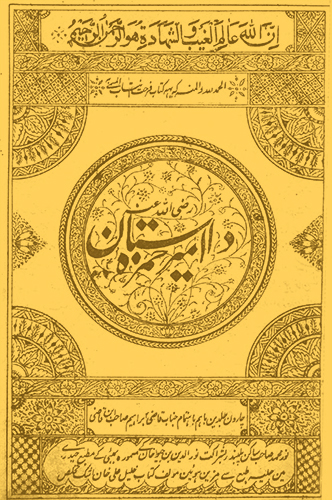

One of the most popular dastans in South Asia was Dastan-i Amir Hamzah (the Dastan of Amir Hamzah). It had its origins in 11th century Iran, but eventually made its way to India where it developed many versions in Persian. Dastan-i Amir Hamzah was popular at the Mughal court where Emperor Akbar was an avid fan.

The hero of the dastan is Hamzah, an uncle of the Prophet Muhammad, who is depicted as a great warrior and supporter of his nephew in early Islamic sources. The adventures of the Hamzah of the dastan, however, are based on fantasy. In the dastan, Amir Hamzah is begged by the wise vizier of Naushirvan, the king of Persia, to help the latter fight his enemies. The gallant Hamzah agrees and fights many battles. He also falls in love with Naushirvan’s daughter, Mahnigar, and seeks her hand in marriage, which requires him to fight more battles and vanquish more enemies. He is accompanied in his travails by his trusted companions, the laconic and serious Muqbil, skilled in archery, and the dishonest but loyal ‘Amr the ‘Ayyar. ‘Ayyars were skilled in espionage and disguises and were notorious for their trickery and special equipment (much like the ninjas). ‘Amr is not only an exceptionally talented ‘ayyar but is extremely greedy even by the low standards of his profession.

As luck would have it, before he could wed Mahnigar, Amir Hamzah is wounded in a battle and is rescued by Shahpal, the king of paris (fairies) who requests that Hamzah help him regain his kingdom in the magical world of Qaf that had been overtaken by demons. Consequently, Amir Hamzah spends eighteen years in the supernatural world of Qaf fighting sorcerers and demons, who can cast such potent spells they can create entire worlds of illusion called tilism. Amir Hamzah and his companions can never be sure whether they are operating in a tilism or in the world of Qaf (which itself is magical) and had to resort to all sorts of ways to break the spells, often with help from saintly figures. Incidentally, an alternative title for the dastan, especially its version based on selections from earlier ones is, Tilism-i Hosh Ruba, The Sense-stealing Tilism.

After eighteen years of adventures, Amir Hamza is finally able to pay his debt to Shahpal. He returns to marry Mahnigar. They have a son named Qubad, but Amir Hamza’s adventures do not end there. He is compelled to fight other enemies and demons until he is called back to Arabia by his nephew, the Prophet Muhammad, to help him fight the enemies of Islam.

When, starting in the 16th century, Urdu became a medium of literary production, dastans began to be composed in it as well. This included versions of Dastan-i Amir Hamzah that were popular enough to have professional story-tellers, called dastan-go or qissah-khvan. Owing to its popularity and the richness of its language, John Gilchrist, head of the Hindustani Department at Fort William College, Calcutta, commissioned a teacher at the department, Khalil Ali Khan Ashk who was also a dastan-go, to publish a printed version of the dastan. Ashk produced the first printed edition of Dastan-i Amir Hamzah in 1801. This makes it not only the earliest printed edition of the dastan but also one of the earliest printed books in Urdu. Ashk’s version consisted of about 500 pages spread over four volumes. It was published many times in the subsequent decades in Delhi, Lucknow, and Bombay. Many of these editions were published by the famous Munshi Nawal Kishore of Lucknow, who published another version by Abdullah Bilgrami in 1871. By the 1920s, the rise of the novel and changing tastes eclipsed the fortunes of dastans and they fell out of favor.

The edition included here is the 1863 edition of Askh’s version that was published from Bombay.

Urdu has been part of language instruction at UC Berkeley since the late 1950s. UC Berkeley also runs the Berkeley Urdu Language Program in Pakistan (BULPIP) in collaboration with the American Institute of Pakistan Studies. In addition, the Institute for South Asia Studies launched the Berkeley Urdu Initiative in 2011 to further promote the study of Urdu at Cal. The leading light for many of the Urdu-related events and activities is Dr. Gregory Maxwell Bruce, the Urdu language instructor, who joined the Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies in the Fall of 2016.

Contribution by Adnan Malik

Curator and Cataloger for the South Asia Collection

South/Southeast Asia Library

Title: Dāstān-i Amīr Ḥamzah razī Allāh ʻanh

Authors: unknown

Imprint: Bambaʼī : Maṭbaʻ Ḥaydarī, 1280 [1863].

Edition: n/a

Language: Urdu

Language Family:

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (UC Berkeley)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100188630

Other online editions:

- The Romance Tradition in Urdu : Adventures from the Dastan of Amir Hamzah / translated, edited, and with an introduction by Frances W. Pritchett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991. Introductory material from the printed edition (modified and corrected wherever appropriate) and the longer translation of the Bilgrami edition.

- Text of Bigrami/Naval Kishore edition (Rekhta: The Largest Website of Urdu Poetry)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Dāstān-i Amīr Ḥamzah razī Allāh ʻanh. Bambaʼī : Maṭbaʻ Ḥaydarī, 1280 [1863].

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Sanskrit

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

There is little doubt that Kālidāsa is one of the most celebrated poets not only in Sanskrit literature but in all of South Asian history. His works represent the acme of Sanskrit poetry and became the model for subsequent poets in Sanskrit as well as most of the major languages of the region. Despite his celebrity and the reverence for his works, very little is definitively known about Kālidāsa. Based on tradition and meagre references to his own life in his works, most scholars agree that he lived in early 5th century CE in the city of Ujjain, located roughly at the center of the Indian peninsula.

Abhijnanasakuntala (The Recognition of Shakuntala), is based on an episode taken from the great Indian epic, the Mahabharata. Kālidāsa retains the basic plot line of the episode but alters it in key ways to adapt it to the stage and make it more romantic. The story revolves around a beautiful maiden named Shakuntala who is the daughter of an ascetic sage and a heavenly nymph. Abandoned by her parents, she was raised in the hermitage of another sage who found her in the care of a flock of “shakunta” birds. Hence, he named her Shakuntala, i.e., protected by shakunta birds. One day, she falls in love with a visiting king named Dushyant who gives her a ring as the token of their love and promises to return to take her with him. In his absence Shakuntala gives birth to a son. Due to a curse, he forgets about her and only recalls her when he encounters the ring again after many years. Their son, Bharata, goes on to become the first emperor of India whose descendants are the protagonists of the Mahabharata.

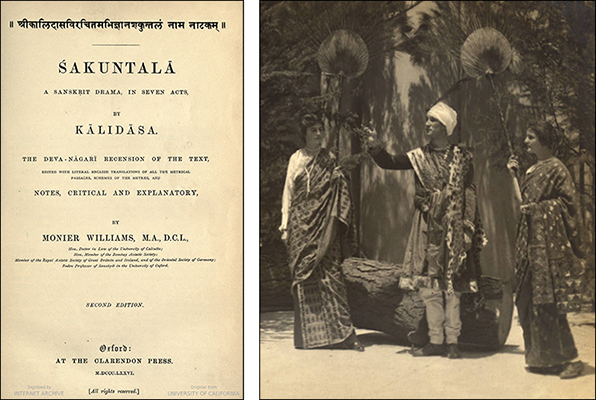

Of all his works, Kālidāsa’s Abhijnanasakuntala became the most world-renowned after it was translated into English by Sir William Jones in Calcutta in 1789. Translations in German and French appeared subsequently. The play was to be translated into all these languages, and many more, numerous times by prominent linguists and indologists of the 19th and 20th centuries. Among these is the translation featured here by the famous indologist Sir Monier Monier-Williams.

Scholarly interest in Sanskrit in European and American academia is not only due to the language’s own rich literary tradition but also because it is the sacred language of the Hindu, Buddhist and Jain religious traditions. Even though the Buddhist and Jain traditions initially used other languages they eventually switched to Sanskrit, as it was the language of high culture, philosophy, and scholarly discourse in ancient India. The linguistic influence of Sanskrit on local South Asian languages is comparable to Latin and ancient Greek in Europe.

Vedic Sanskrit, an ancient form of Sanskrit in which the Vedas, the most ancient Hindu scriptures, are composed, is an important source for the study of the evolution of Indo-European languages. In fact, having been orally composed between 1500 and 1200 BCE, the Vedas are among the oldest literary creations in any Indo-European language.

The study and teaching of Sanskrit at UC Berkeley goes back to the 1890s and includes an impressive list of world renowned scholars and interest in Kālidāsa has also been keenly pursued here. Among others, Professor Arthur W. Ryder, Professor of Sanskrit, published a translation of a selection of Kālidāsa’s works in 1912 that included Abhijñānaśākuntala. This translation became the basis for a performance of the play in the Greek Theater in 1914. The play continues to be widely performed into the present day. Today, Professor Robert P. Goldman is UC Berkeley’s Magistretti Distinguished Professor of Sanskrit. He is also the director, general editor, and principal translator of the recently published multi-volume critical edition of a fully annotated English translation of Valmiki’s famous epic, Ramayana, and has received many awards and fellowships.

Contribution by Adnan Malik

Curator and Cataloger for the South Asia Collection

South/Southeast Asia Library

Special thanks to Sally Sutherland Goldman, Senior Lecturer in Sanskrit

Department of South and Southeast Asian Studies

Title: Śakuntalā, a Sanskrit drama, in seven acts. The Deva-Nāgari recension of the text, ed. with literal English translations of all the metrical passages, schemes of the metres and notes, critical and explanatory by Monier Williams.

Authors: Kālidāsa

Imprint: Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1876.

Edition: 2nd

Language: Sanskrit

Language Family: Indo-European, Indo-Aryan

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (UC Berkeley)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/002751897

Other online editions:

- Translations of Shakuntala and Other Works by Kālidāsa (Internet Archive)

- Monier-Williams translation and Sanskrit text (2nd ed.) (Internet Archive)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Śakuntalā, a Sanskrit drama, in seven acts. The Deva-Nāgari recension of the text, ed. Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1876.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Tibetan

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Rgyal rabs gsal ba’i me long is a famous historical work by Sakyapa Sonam Gyaltsen (1312-1375). The text presents Tibetan history such as the origins of the Tibetans, how dharma arrived in Tibet, when Lhasa became the main capital and the Jokhang and Ramoche temples were built. Sakyapa Sonam Gyaltsen was a ruler of Sakya which had a preeminent position in Tibet under the Yuan dynasty. He is considered the greatest Sakya scholar of the 14th century and served as ruler for a short term from 1344 to 1347.

According to McComas Taylor who authored the English translation, “It ranks among the great works of early Tibetan historiographical writing, but outshines all others in both the depth and breadth of its coverage. . . The text is a rich blend of history, legend, poetry, adventure and romance. It may properly be regarded as a literary work, albeit a morally and spiritually uplifting one.” He writes further: “This text has been known by several names. The original Tibetan title, and the one that is most widely recognized, is Clear Mirror on Royal Genealogy, although in the final paragraph the author himself calls the work Clear Mirror on the History of the Dharma. The first wood-block edition was printed at the Tsuglagkhang in 1478 and is therefore known as the Lhasa redaction.”

Ever since China annexed Tibet as a province in 1951, the Tibetan language has been proscribed in schools in favor of Mandarin.[1] Tibetan Buddhism and its literature are thus at present maintained by a worldwide diaspora, drawing some strength from Tibetan communities of the southern Himalaya beyond the Chinese border.[2] There are numerous (and mutually unintelligible dialects) of modern spoken Tibetan, and the study of these dialects — essential for the study of cultural practices such as pilgrimage — is becoming an area of research at several institutions, including UC Berkeley.[3] This historical text has been translated into Mongolian, German, and Chinese, and various sections have appeared in Italian and Russian.

Contribution by Susan Xue

Head, Information and Public Services &

Electronic Resources Librarian, C.V. Starr East Asian Library

Sources consulted:

- Garry, Jane, and Carl R. G. Rubino. Facts About the World’s Languages: An Encyclopedia of the World’s Major Languages, Past and Present. New York: H.W. Wilson, 2001.

- May, Stephen. Language and Minority Rights: Ethnicity, Nationalism and the Politics of Language. New York: Routledge, 2012.

- Institute for South Asia Studies, UC Berkeley

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Rgyal rabs gsal ba’i me long

Title in English: Clear Mirror on Royal Genealogy

Author: Bsod-nams-rgyal-mtshan, Sakyapa Sonan Gyaltsen, 1312-1375.

Imprint: Pe cin: mi rigs dpe skrun khang, 2002.

Edition: Par gzhi 1

Language: Tibetan

Language Family: Sino-Tibetan

Source: Buddhist Digital Resource Center

URL: https://www.tbrc.org/#!rid=W00KG09730

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Bsod-nams-rgyal-mtshan, Sakyapa Sonan Gyaltsen, and B I. Kuznet︠s︡ov, ed. Rgyal Rabs Gsal Baʼi Me Long: The Clear Mirror of Royal Genealogies ; Tibetan Text in Transliteration with an Introduction in English. Leiden: Brill, 1966.

- Bsod-nams-rgyal-mtshan, Sakyapa Sonan Gyaltsen. Translated into English by McComas Taylor, and Yuthok Choedak. The Clear Mirror: A Traditional Account of Tibet’s Golden Age. Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion Publications, 1996. Preview in Google Books.

- Bsod-nams-rgyal-mtshan, Sakyapa Sonan Gyaltsen. Translated into Chinese by Liqian Liu. Xizang Wang Tong Ji. Beijing Shi: Min zu chu ban she, 2000.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)