Tag: BL Afro-Asiatic Semitic

Modern Hebrew

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

ורבים מצאו שראוי לתמוך בה ואין פוצה פה כנגד המצוה הזאת. אפס לכלל מעשה לא באו, חס ושלום שאנשי בוצץ מתרפים מדבר מצוה להתעסק בה, אבל כלל זה מסור בידם כל שאפשר לעשותו מחר אפשר לדחותו גם למחרתיים ויש מחרתיים לאחר זמן. וכשבאו ואמרו לפרנס החודש קריינדל טשרני גוועת ברעב ענה ואמר באמת באמת קריינדל טשרני גוועת ברעב.

And many saw fit to support her and none objected to this mitzvah. But they failed to act. Heaven forbid that the people of Buczacz would neglect performing a mitzvah, but this was their fixed rule: whatever can be done tomorrow can be put off to the day after tomorrow, and there is another tomorrow after that. And when they came and said to the month’s community head, “Kreindel Tcharny is dying of hunger,” he responded, “Really, really, Kreindel Tcharny is dying of hunger.” (trans. Robert Alter)

The novella And the Crooked Shall be Straight, which appeared in 1912, a year before the 24-year-old Agnon left Palestine for what would prove a decade-long stay in Germany, established his reputation as a major new voice in Hebrew literature. In it, he perfected his signature style, a supple and resonant synthesis of early rabbinic Hebrew, the Hebrew of the medieval commentaries, and the language of Early Modern pious literature. The power of the story came across in translation as well: Walter Benjamin, destined to become one of the most original critics of his age, read it in the 1919 German version together with other stories and deemed Agnon a great writer.

The plot is one that had some currency among European writers—one thinks of Balzac’s Colonel Chabert, the story of an officer in Napoleon’s army presumed dead in battle who after some years returns home to find his wife married to another man, like the protagonist of Agnon’s novella. The abundant deployment of traditional Hebrew sources here is shrewdly ironic. The title itself, a quotation from Isaiah 40:4, is turned back on itself because in the story nothing tragically bent will be made straight. The citation of a well-known talmudic dictum, “A poor man is as good as dead,” acquires a new, macabre meaning. The original sense is that a poor man is so miserable and so ill-regarded that he might as well be dead. But Agnon’s Menashe Haim—his name means “life-forgetter”—becomes a living dead man. After he sells his mendicant’s rabbinic letter of recommendation, the buyer is found dead with the seller’s name on the letter; his grave is marked with a tombstone bearing Menashe Haim’s name; his wife, who had been childless, has a baby with her new husband; and Menashe Haim, discovering this, retreats to olam hatohu, a borderline realm between life and death, in the end living in a cemetery. All this is a naturalistic adaptation of Gothic fiction, to which Agnon was drawn, populated by wandering souls, revenants, and ghosts. Perhaps the one unironic allusion to a traditional text is to Qohelet (Ecclesiastes), recurring in the story. At one point, the narrator says, “As the rhapsode (hameilitz) Schiller has said, “A generation comes and a generation goes but hope endures forever.” Whether Schiller actually said this, a one-word substitution has been made in the quotation of Qohelet 1:4, which reads, “A generation comes and a generation goes but the world endures forever.” In Menashe Haim’s story, hope is a mockery. One may recall Kafka’s somber remark, “There is hope but not for us.”

Contribution by Robert Alter

Emeritus Professor of Hebrew and Comparative Literature,

Department of Near Eastern Studies

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: והיה העקוב למישור [Ṿe-hayah he-ʻaḳov le-mishor]

Title in English: And the Crooked Shall be Straight

Author: Agnon, Shmuel Yosef, 1887-1970; Illustrated by Joseph Budko.

Imprint: Berlin, Jüdischer Verlag, 1919.

Edition: n/a

Language: Modern Hebrew

Language Family: Afro-Asiatic, Northwest Semitic

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Maryland, College Park)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011626839

Other online editions:

- Und das Krumme wird gerade: Geschichte eines Menschen mit Namen Menaschen Chajim … / das hat verfasst und hat es aufgeschrieben G.S. Agnon; [aus dem Hebräischen von Max Strauss]. Berlin: Jüdische Verlag, 1920.

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Ṿe-hayah he-ʻaḳov le-mishor / be-tseruf heʻarot, beʼurim u-marʼe meḳomot me-et Naftali Ginaton. Yerushalayim: Shoḳen, 1965.

- Sipurim: Ṿe-hayah he-ʻaḳov la-mishor; Tehilah. Yerushalayim: Shoḳen, 723, 1963.

Explore Modern Hebrew language and literature at UC Berkeley:

- Learn Hebrew with Rutie Adler

- Study Modern Hebrew literature with Chana Kronfeld

- Choose the undergraduate Minor in Hebrew

- Pursue advanced study in UCB’s Near Eastern Studies and Comparative Literature graduate programs in Hebrew and Hebrew literature

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Amharic

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

With over 2,000 vernacular languages, sub-Saharan Africa includes approximately one-third of the world’s languages.[1] Many of these will likely disappear in the next hundred years, displaced by dominant regional languages like Amharic.

Amharic, alternately known as Abyssinian, Amarigna, Amarinya, Amhara, or, simply, Ethiopian, is a Semitic language spoken by over 25 million people. It is part of the Semitic branch of the Afroasiatic language group, which spans, as the name suggests, two continents, primarily West Asia as well as North Africa and the Horn of Africa. In the 13th century, it evolved as a spoken language and replaced Ge’ez as the common means of communication in the imperial court where it was referred to as the language of the king.[2] Today, Amharic is spoken as the first language (L1) by the Amhara of the northwest Highlands of Ethiopia. As the official language of Ethiopia, it has become the lingua franca of the country.[3]

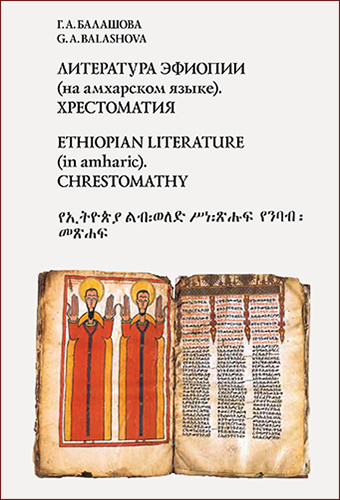

Beyond Amharic’s inherent importance in the realm of politics, education, and business as a result of its privileged status as the official language of Ethiopia, it is also a major literary language in the country. Early (pre-20th century) Ethiopian literature often took on religious themes and was published in the ancient Semitic language of Ge‘ez. However, by the turn of the 20th century, literary publications in Amharic became more common, signaling the language’s ascent. The featured text here, Ethiopian Literature (in Amharic): Chrestomathy, a collection of seventeen samples of Ethiopian literature by various authors, captures the expansion of Amharic influence in literary publications. The collection covers one-hundred years of Ethiopian literary prose beginning with “Story Born at Heart” by Afewerk Ghebre Jesus, originally published in 1908, up to the early 2000s with a piece by one of the great modern Ethiopian writers, Adam Reta. The collection, generously adorned with illustrations throughout, was designed for students of Amharic philology.

At UC Berkeley, based on research interest and student demand, especially from heritage students, with Title VI funding through the Center for African Studies, Amharic language study (at the elementary and intermediate levels) has been offered since the fall of 2019. Students enrolled in Amharic are among the few in the whole of the United States formally studying the language and are at the vanguard in recognizing Africa’s increasing importance demographically, socially, and culturally.[4]

Contribution by Adam Clemons

Librarian for African and African American Studies, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Moseley, Christopher, and Alexandre Nicolas. Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. Paris: UNESCO, 2010.

- Meyer, Ronny. “Amharic as Lingua Franca in Ethiopia.” Lissan: Journal of African Languages and Linguistics. 20 1/2 (2006).

- Ethnologue: Languages of the World (accessed 5/16/20)

- Saavedra, Martha and Leonardo Arriola. “UC Berkeley Needs to Support African Language Programs” Daily Californian (February 22, 2019) (accessed 5/16/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Ethiopian Literature (in Amharic): Chrestomathy

Author: Galina (Galina Aleksandrovna) Balashova, compiler.

Imprint: Lac-Beaport, Quebec : MEABOOKS Inc., 2016. (Baltimore, Md. : Project MUSE, 2015.)

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Amharic

Language Family: Afro-Asiatic, South Semitic

Source: Project Muse

URL: https://muse-jhu-edu.libproxy.berkeley.edu/book/48900 (UCB access only)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Ethiopian literature (in Amharic): Chrestomathy / G.A. Balashova, comp. Lac-Beauport, Quebec: MeaBooks Inc, 2016.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Ancient Egyptian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

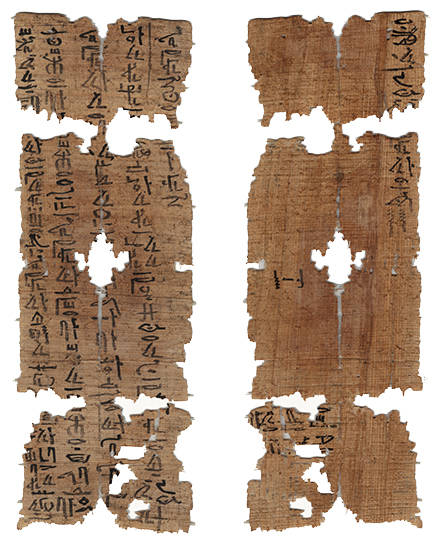

Ancient Egyptian is a language that was spoken in and around the Nile River valley from the 4th millennium BCE through the 11th century CE. The earliest form of this language was written in the Hieroglyphic script. Soon after the development of Hieroglyphs, the availability of papyrus as a light, portable writing material and the complexity of drawing complete Hieroglyphic signs led to the development of Hieratic. This cursive form of the ancient Egyptian script is what an individual named Heni used to write a letter to his deceased father, Meru, sometime between 2160 and 2025 BCE. Heni’s composition is one of a handful of texts known as “Letters to the Dead,” which have been found throughout Egypt written on materials as diverse as pottery, figurines, linen, and stone stelae. Although this genre of text is attested for a period of nearly two thousand years, only a handful of examples survive, all of which share the common goal of communicating a wish or desire from the living to the dead.

The letter of Heni, written in vertical columns, as was typical for Hieratic of this time period, opens with a greeting to Meru before imploring him to intercede on his son’s behalf and offer aid. Heni believes he is being falsely accused of harming someone, insisting the wrong was instigated by other parties. Unfortunately, the details of the event are lacking. These letters are frustratingly vague, as it was assumed that the intended audience — usually a close relative or acquaintance — knew the specifics of the situation. The letter was folded and addressed like letters sent among the living. That is to say, the address was written on the outside (the two short lines written horizontally towards the bottom of the verso of the papyrus): the nobleman (iry-pat), count (haty-a), overseer of priests, Meru. In order to ensure the message was delivered, Heni deposited the small papyrus in his father’s tomb. Whether or not his father (or the living judges) recognized his plea of innocence, we will never know.

Several millennia later, Heni’s papyrus was found during the archaeological excavations of George A. Reisner. Working under the patronage of Phoebe A. Hearst, Reisner excavated the site of Naga ed-Deir between 1901 and 1904. The letter was found in the tomb of Meru (N.3737), which was decorated with images of him enjoying everyday life. The papyrus was shipped by Reisner to Germany for conservation, where it remained until after World War II. When financial difficulties compelled Phoebe Hearst to withdraw funding for the Berkeley Egyptian Excavations in 1905, George A. Reisner was appointed to the faculty at Harvard University and to the curatorial board at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston. A young, enterprising curator at the MFA, William Kelly Simpson, knew of papyri excavated by Reisner and later sought them out in Germany. With Simpson’s help, the papyrus — along with several others — traveled from West Berlin to the MFA. After securing them in Boston, Simpson published the first translation of this text. Despite earlier inquiries from faculty at UC Berkeley, it was not until the 2000s that Professor Donald Mastronarde of the Berkeley Department of Classics ascertained the whereabouts of these papyri and engineered their return to Berkeley. The Letter to the Dead, along with numerous other ancient Egyptian papyri, are now housed in the Center for the Tebtunis Papyri at The Bancroft Library, as part of the Egyptian collections acquired by Phoebe A. Hearst between 1899 and 1905.

Courses in Ancient Egyptian are taught at UC Berkeley in the Department of Near Eastern Studies as part of a program in Egyptology. Students can take classes in several phases of the language, including Old, Middle, and Late Egyptian, and Demotic.

Emily Cole, Postdoctoral Scholar

The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, The Bancroft Library

Source consulted:

Simpson, William Kelly. “The Letter to the Dead from the Tomb of Meru (N 3737) at Nag’ Ed-Deir.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, vol. 52, 1966, pp. 39–52. JSTOR.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Letter to the Dead

Author: Heni

Registration Number: Papyrus Hearst 1282

Imprint: 9th or 10th Egyptian Dynasty. First Intermediate Period (Between 2160 and 2025 BCE)

Language: Ancient Egyptian

Language Family: Afro-Asiatic, Semitic

Source: The Center for the Tebtunis Papyri, The Bancroft Library (UC Berkeley)

URL: http://dpg.lib.berkeley.edu/webdb/apis/apis2?invno=P%2eHearst%2e1282&sort=Author_Title&item=1

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)