Tag: BL North America

Yiddish

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

דער גרויסער וועלט-פּראָגרעס האָט זיך אַהין אַרייַנגעכאַפט און האָט איבערגעדרייט די שטאָט מיטן קאַָפּ אַראָפּ, מיט די פֿיס אַרויף.

The great progress of the world has reached Kasrilevke and turned it topsy-turvy.

– From narrator’s foreword to the Kasrilevke stories (1919)

אַיין אַיינשרומפּעניש! ווען האָט געקאָנט ארויס דער צאַפּען, אַיינגעזונקען זאָל ער ווערען? … אַ, ברענען זאָלסט דו, שלים־מזל, אויפ’ן פייער!

און גרונם … דערלאַנגט דעם אַ רוק מיט’ן בייטש־שטעקעל אין זייט אַריין. דאָס פערדעל טהוט אַ פּינטעל מיט די אויגען, לאָזט־אַראָפּ די מאָרדע, קוקט אָן אַ זייט און טראַכט זיךְ׃ פאַר וואָס קומט מיר, אַשטייגער, אָט דער זעץ? גלאַט גענומען און געבוכעט זיךְ! ס’איז ניט קיין קונץ נעמען אַ פערד, אַ שטומע צונג, און שלאָגען איהם אומזיסט און אומנישט!

The driver of the wagon with the water barrel was beside himself! “An empty barrel! … May my helper shrivel up! How could that plug, may it sink into the earth, have come out? May you burn up, wretch that you are!” The last remark was addressed to the little horse, as he struck it with the whip handle. The horse blinked, lowered its chin, and looked aside, thinking, “What have I done to deserve this whack? It’s no trick, you know, to hit a dumb animal for no reason whatsoever.”

– From the story “Fires”

Yiddish is the thousand-year-old language of European (Ashkenazic) Jews. Written from right to left in Hebrew characters, it is derived from German and includes many Hebraic and Slavic elements. It is used for everyday purposes as well as for a rich variety of religious and secular literature, ranging from medieval times to the 21st century. Most Yiddish users were annihilated during the Holocaust of World War II, yet the language continues to thrive in the United States, Israel, and Europe.

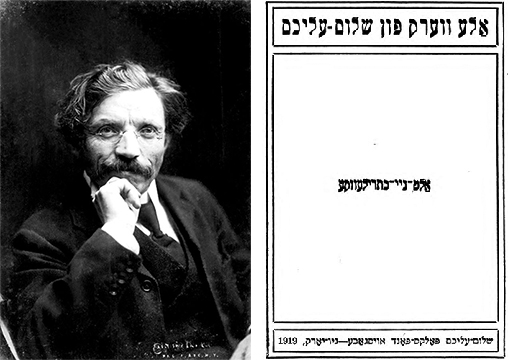

Arguably the best-known Yiddish writer, Sholem Aleichem (Sholem Rabinovich, Ukraine 1859 – United States 1916) was a founding father of modern Yiddish literature. A supreme humorist, he created the literary persona of “Sholem Aleichem” and tapped into the energies of the Eastern European spoken Yiddish idiom. In a variety of genres, he invented modern Jewish archetypes, myths, and fables of unique imaginative power and universal appeal. Sholem Aleichem’s “Tevye” stories provided the basis of the popular mid-20th century musical Fiddler on the Roof. He founded the Folks-bibliotek publishing house (Kiev, 1888) to encourage writers he admired, and identify new talent. In his satirical, yet warm Kasrilevke stories of the 1900s, he created the quintessential fictional shtetl. Its poverty-stricken residents aspired to modernity. Though plagued by backwardness, they continued to dream of redemption.

Following the death in 1916 of the beloved Sholem Aleichem, multi-volume editions of his collected works were published widely. This 1919 edition is printed in the Yiddish spelling prevalent at the time, with transliterations of Germanic linguistic elements; this was meant to help “legitimize” Yiddish (then considered a “jargon”). These transliterations are not used in modern standardized Yiddish orthography. The story “Fires,” from which this selection is taken, underlines the actual lack of progress in the fictional town of Kasrilevke, which prides itself on striving for modernity. The aside, giving voice to the abused horse in the midst of this municipal crisis, is typical of the creative yet plainspoken genius which made Sholem Aleichem so popular.

While the number of native speakers of Yiddish continues to dwindle, Yiddish at Berkeley is thriving. In addition to the esteemed annual conference on Yiddish Culture, we have a wide range of courses dealing with the life and culture of Ashkenazic Jewry, a diverse faculty committed to the preservation and scholarly investigation of Yiddish, and an ever-growing number of students who are pursuing academic futures exploring Jewish culture in the traditional languages of the Jewish people. Students interested in Yiddish at Cal can pursue their interests in the departments of German, Comparative Literature, History, or through the program in Jewish Studies.

Contribution by Yael Chaver

Lecturer in Yiddish, Department of German

Title: Alṭ-nay-Kas̀rileṿḳe

Title in English: Old-New Kasrilevke

Author: Sholem Aleichem, 1859-1916

Imprint: Nyu-Yorḳ : Shalom-ʻAlekhem folḳs-fond, 1919.

Edition: in Ale Verk, Sholom Aleichem

Language: Yiddish

Language Family: Indo-European, Germanic

Source: The Internet Archive (Yiddish Book Center)

URL: https://archive.org/stream/nybc200084

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Sholem, Aleichem. Alṭ-nay-kas̀rileṿḳe. Nyu-Yorḳ: Shalom-ʻAlekhem folḳs-fond, 1919.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Spanish (Europe)

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

If you walk down the street in many parts of the world and ask a stranger who fought the windmills, they would most probably answer Don Quixote. But they would not necessarily know the name of its author, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1547-1616). This not-so-prolific dramaturge, poet and novelist has nonetheless had a major impact on the development of Western literature, influencing his English contemporary William Shakespeare, 19th-century French author Gustave Flaubert, and 20th-century Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges, just to name a few.

Cervantes did not come to prominence until much later in his life. His experiences as a soldier, a captive and a witness to the struggles of the Spanish empire shaped his distinctive oeuvre: a literary world of experimentation, as can be seen in his Exemplary Novels (1613), a world in which possibilities of reconciliation between conflictive individuals, ideals and desires remained hollow, inconclusive and, in many cases, without avail. Among other factors, what distinguishes Cervantes’ literary production is its unclassifiable nature, making it hard to try and fit the works in their presumed corresponding genre. One good example is his posthumous work The Travails of Persiles and Sigismunda (1616), where the Byzantine novel is mutilated to such an extent that, at points, it becomes almost unrecognizable.

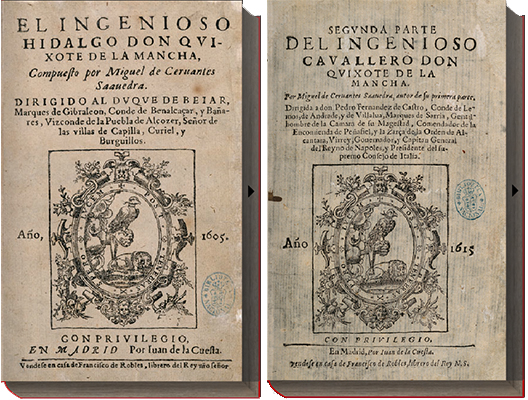

Yet this unfittedness is most evident in Don Quixote (Part I published in 1605; Part II in 1615). The confusion between reality and fiction, the untrustworthiness of the multiple narrators, the intentional errors and misnomers, the three-dimensionalism of Don Quixote’s squire, Sancho, who has a love-hate relationship with his master, the utter destruction of the chivalric world, and the encounter with oppressed minorities are but some of the factors that have undoubtedly contributed to the sustained appeal of Don Quixote. The protagonist, an old man who “loses his mind” reading novels of chivalry, was, in Western literature, a pioneering self-proclaimed “hero.” He offers and imposes his help unto people who rarely take him seriously. Moreover, he only becomes popular, within his diegetic world, when in Part II he is defined by others as a caricature. This caricature remains dominant in the collective imaginary of readers, as can be seen, for example, in Picasso’s well-known depiction of the character.

Although most masterpieces ultimately attempt to challenge a comfortable experience of reading where we readily identify with fictitious characters; Don Quixote still manages to attract the empathy of its readers who may or may not closely identify with the knight-errant. Don Quixote is beaten up, both physically and metaphorically, yet his innocent, albeit selfish at times, intentions have ultimately won the hearts of a diverse audience over the centuries.

Today, the Spanish language, or Castilian as it is referred to in Europe, has grown from around 14 million speakers at the time of Cervantes to 477 million native speakers worldwide. It is now the second most used language for international communication and the most studied languages on the planet.[1] At Berkeley, Spanish is one of the most widely used languages for scholarship after English, particularly in departments such as Anthropology, Comparative Literature, Ethnic Studies, Film & Media, Gender & Women’s Studies, History, Linguistics, Political Science, and Rhetoric. Interdisciplinary graduate programs in Latin American Studies, Medieval Studies, Romance Languages and Literature, and Medieval and Early Modern Studies also require reading of original texts in Spanish.

Nasser Meerkhan, Assistant Professor

Department of Near Eastern Studies & Department of Spanish & Portuguese

Source consulted:

- Elias, D. José Antonio. Atlas historico, geográfico y estadístico de España y sus posesiones de ultramar. Barcelona : Imprenta Hispana, 1848; Hernández Sánchez Barbara, Mario. “La población hispanoamericana y su distribución social en el siglo XVIII,” Revista de estudios políticos, no.78 (1954); López, Morales H, and El español: una lengua viva. Informe 2017. Madrid : Arco Libros, S.L. : El Instituto, 2017.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha

Author: Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de, 1547-1616.

Imprint: En Madrid : por Iuan de la Cuesta, 1605, 1615.

Edition: 1st

Language: Spanish (Europe)

Language Family: Indo-European

Source: Biblioteca Nacional de España

URL: http://quijote.bne.es/libro.html (requires Flash)

Other online editions:

- El ingenioso hidalgo don Quixote de la Mancha / compuesto por Miguel de Ceruantes Saauedra. En Madrid : por Iuan de la Cuesta, 1605.

- Segunda parte del ingenioso cauallero don Quixote de la Mancha / por Miguel de Ceruantes Saauedra, autor de su primera parte. En Madrid : por Iuan de la Cuesta, 1615.

- The History of Don Quixote. Translated into English by J.W. Clark. Illustrated by Gustave Doré. New York, P.F. Collier, 1871 .

Select print editions at Berkeley:

Considered to be the most translated work every written, the Library has editions in French, German, Hebrew, Armenian, Quechua, and more. The earliest and best illustrated editions reside in The Bancroft Library.

- El ingenioso hidalgo don Quixote de la Mancha. Burgaillos. Published Impresso con licencia, en Valencia : En casa de Pedro Patricio Mey : A costa de Iusepe Ferrer mercader de libros, delante la Diputacion, 1605.

- Segunda parte del ingenioso cauallero don Quixote de la Mancha. En Valencia : En casa de Pedro Patricio Mey, junto a San Martin : A costa de Roque Sonzonio mercader de libros, 1616.

- Vida y hechos del ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha. Nueva edicion, corregida y ilustrada con 32 differentes estampas muy donosas, y apropriadas à la materia. Amberes, Por Henrico y Cornelio Verdussen, 1719.

- El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha / por Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra ; obra adornada de 125 estampas litográficas y publicada por Masse y Decaen, impresore litógrafos y editores, callejon de Santa Clara no 8. México : Impreso por Ignacio Cumplido, calle de los Rebeldes num. 2, 1842.

- Don Quixote / Miguel de Cervantes ; a new translation by Edith Grossman ; introduction by Harold Bloom. New York : Ecco, c2003.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Nahuatl

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

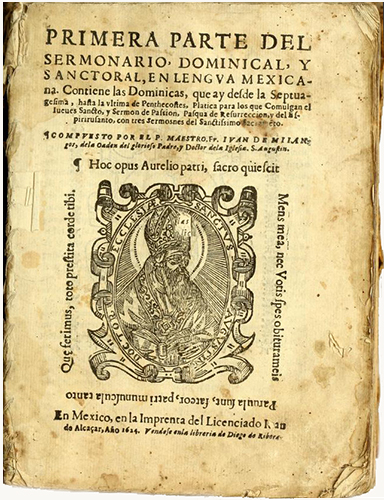

Written in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, the Primera parte del sermonario, dominical, y sanctoral, en lengua mexicana was published in Mexico City in 1624 at Juan de Alcázar’s printing press. The title of this collection of sermons is representative of the early colonial printing in Mexico City as well as the Augustinian order’s testament to the proselytizing efforts of the Catholic Church in Mexico. Only the first part of this Nahuatl text was ever published. Its author, Fr. Juan de Mijangos, is also well known for his Espejo Divino (1607).

As noted by Hortensia Calvo, director of the Latin American Library at Tulane University, Spain’s ideological, political and administrative control was possible with the early colonial press: “The first presses were brought to Mexico City and Lima for the explicit purpose of aiding missionaries in the Christianization of the native population.”[1] However, in the 17th century, following the Conquest, the Spanish occupiers dealt with many different populations of the region, hence many books were printed in the indigenous languages and, most importantly, not all texts were created for colonial or religious purposes. James Lockhart shows that, as early as 1545, the Nahuas of central Mexico adopted the Latin alphabet for their own purposes, beyond the interests of the colonial authorities and missionaries.[2] Indeed, former Berkeley professor José Rabasa argues that the “Alphabetical writing does not belong to rulers; it also circulates in the mode of a savage literacy. Bearing no trace of Spanish intervention in its production, the Historia de Tlatelolco exemplifies a form of grassroots literacy in which indigenous writers operated outside the circuits controlled by missionaries, encomenderos, Indian judges and governors, or lay officers of the crown.”[3] Several such texts have been digitized by the French National Library, including the Diario de Don Domingo de San Anton Muñón Chimalpáhin Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin (1579-1660).

Nevertheless, Marina Garone Gravier notes “there was a lack of in-depth knowledge of Nahuatl by some who composed these early sermons related books.”[4] Since the foundation of the Aztec Empire in 1325, Nahuatl played an essential role in daily workings. Published 103 years after the fall of the Aztec in 1521, the sermon book featured here evinces the continuation of Nahuatl during the early days of the Spanish Empire. Frances Kartunnen points out: “At the time of Spanish Conquest of Mexico [Nahuatl] was the dominant language of Mesoamerica, and Spanish friars immediately set about learning it. Some of them made heroic efforts to preach in Nahuatl and to hear confession in the language. To aid in these endeavors, they devised an orthography based on Spanish conventions and composed Nahuatl language breviaries, confessional guides, and collection of sermons, which were among the first books printed in the New World. Nahuatl speakers were taught to read and write their language, and under Friars’ direction the surviving guardians of an oral tradition set down in writing particulars of their shattered culture in the Florentine Codex and other ethnographic collections of Fray Bernardino de Sahagún and his contemporaries.”[5]

Today there are over one million Nahuatl speakers in Mexico and in the diasporic communities in the United States.[6] Yet, there are several dozens of Nahuatl dialects and, since this non-Romance language adopted the Latin Alphabet, it is difficult to apply standard orthographic principles to all of them.[7] Nonetheless, the following are essential textbooks for the teaching and learning of standardized Nahuatl: Richard Andrew’s Introduction to Classical Nahuatl, James Lockhart’s Nahuatl as Written, Michel Launey’s An Introduction to Classical Nahuatl and, for more advanced students, James Lockhart’s edition of Horacio Carochi’s Grammar of the Mexican Language.[8] Many other resources are available in print and digital format; for example, the University of Oregon’s online Nahuatl Dictionary, Molina’s bilingual dictionary Vocabulario en lengua castellana y mexicana (1571), UNAM’s online Gran Diccionario Náhuatl, and the app Vamos a aprender náhuatl.

Nahuatl language courses are available through UCLA’s distance learning program[9] and University of Utah’s Intensive Nahuatl Language and Culture Summer Program in Salt Lake City. The latter program, previously sponsored at Yale, has prepared many contemporary US-based Nahuatl scholars.[10] At UC Berkeley, the Joseph A. Myers Center for Research on Native American Issues has offered annual Nahuatl workshops,[11] and The Bancroft Library holds over 460 items, including the Primera parte del sermonario, dominical, y sanctoral, en lengua mexicana, concerning the Nahuatl language in its renowned Latin Americana Collection.[12]

The librarian for the Caribbean and Latin American Studies has requested this post to be published on September 16, 2019, which is is celebrated as the day of Independence in Mexico.

Contribution by Lilahdar Pendse

Librarian for Latin American Studies, Doe Library

Carlos Macías Prieto

PhD student, Department of Spanish & Portuguese

Sources consulted:

- Calvo, Hortensia. “The Politics of Print: The Historiography of the Book in Early Spanish America.” Book History, vol. 6, 2003, pp. 277–305. JSTOR.

- Lockhart, James. The Nahuas After the Conquest: A Social and Cultural History of the Indians of Central Mexico, Sixteenth Through Eighteenth Centuries. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996.

- Rabasa, José. Writing Violence on the Northern Frontier: The Historiography of Sixteenth-Century New Mexico and the Legacy of Conquest. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2000.

- Gravier, Marina Garone. “La tipografía y las lenguas indígenas: estrategias editoriales en la Nueva España.” La Bibliofilía, vol. 113, no. 3, 2011, pp. 355–374. JSTOR.

- Karttunen, Frances. An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl. Norman: Univ. of Oklahoma Press, 1992.

- Janick, Jules, and Arthur O. Tucker. Unraveling the Voynich Codex. Cham Springer , 2018.

- Andrews, J R. Introduction to Classical Nahuatl. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2003.

- Introduction to Nahuatl, Center for Latin American Studies, Stanford (accessed 9/12/19)

- Distance Learning Language Classes, UCLA (accessed 9/12/19)

- Beginners and Advanced Nahuatl Language and Culture Workshops, UCB (accessed 9/12/19)

- Utah Nahuatl Language and Culture Program (accessed 6/18/19)

- Latin Americana: Mexico and Central America, The Bancroft Library, UCB (accessed 9/12/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Primera parte del sermonario, dominical, y sanctoral, en lengua mexicana : contiene las Dominicas, que ay desde la Septuagesima, hasta la vltima de Penthecostes, platica para los que comulgan el iueues sancto, y Sermon de Passion, pasqua de Resurreccion, y del Espiritusanto, con tres sermosnes [sic] del sanctissimo sacrame[n]to / compuesto por el P. maestro Fr. Iuan de Miiangos, de la Oaden [sic] del glorioso Padre, y Doctor dela Iglesia. S. Augustin. (1624).

Author: Mijangos, Juan de, d. ca. 1625

Imprint: En Mexico : En la imprenta del licenciado Iuan de Alcaçar : Vendese en la libreria de Diego de Ribera : año 1624.

Edition: 1st

Language: Nahuatl

Language Family: Uto-Aztecan

Source: The Internet Archive (John Carter Brown Library)

URL: https://archive.org/details/primerapartedels00mija

Other Nahuatl texts online:

- Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin (1579-1660). Diario de Don Domingo de San Anton Muñón Chimalpáhin, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- Fray Bernardino de Sahagún (1499–1590). Historia general de las cosas de nueva España (The Florentine Codex). World Digital Library (Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana).

- Gran Diccionario Náhuatl [online]. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México [Ciudad Universitaria, México D.F.]: 2012.

- Molina, Alonso de, d. 1585. Vocabulario en lengua Castellana y Mexicana. En Mexico : en casa de Antonio de Spinosa, 1571.

- Online Nahuatl Dictionary (University of Oregon)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- The Bancroft Library has in its collection one of eight surviving copies of Primera parte del sermonario, dominical, y sanctoral, en lengua mexicana (1624) held in U.S. libraries.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

American Sign Language

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

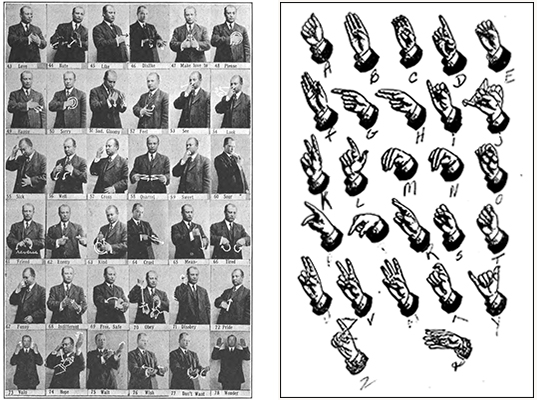

The significance of J. Schuyler Long’s The Sign Language; A Manual of Signs, Being A Descriptive Vocabulary of Signs Used by the Deaf of The United States and Canada cannot be separated from the status of Deaf education at the beginning of the 20th century. Beginning in 1880 at the Second International Congress of the Deaf, educators of the Deaf adopted the practice of oralism, which relied solely on speech to teach the Deaf and forcing them to learn skills such as lip reading. Many in the Deaf community viewed this as an attempt to eradicate sign language in an attempt to forcibly assimilate them into the hearing community.[1] As a result of this forced adoption, fewer Deaf instructors were proficient in American Sign Language (ASL), and fewer children were learning the language fluently.

In response, various Deaf educators took the initiative of documenting ASL, taking advantage of these new formats of photography and film to document and preserve the language. J. Schuyler Long, principal at the Iowa School for the Deaf and a graduate of Gallaudet University, developed in 1910 and reprinted in 1918 a handbook of signs used in ASL, incorporating detailed written descriptions of each sign with photographs illustrating each vocabulary term. For example, for the sign “fascinate”, Long describes the motions as such:

Fascinate — Bring the hand up before the face, with fingers extended except the thumb and forefinger which are brought together as if about to grasp something; bring them nearly together and then draw out slowly from the face (giving the idea of drawing the attention out), giving the face an intent or concentrated look.[2]

Long’s manual also firmly states that ASL is indeed a language, with established vocabulary and dialectical variation. This argument helped Deaf activists show that ASL is more than pantomime.

Today, American Sign Language is one of the languages taught at UC Berkeley. Though it was not established as a language course until 2012, students are now able to take ASL to fulfill the language requirement in their degree programs.[3] Even if students are not enrolled in the course, they can still find ways to learn the language, thanks to the evolution of image based media such as YouTube. Thanks to the efforts of educators and activists, students can understand ASL as not just a series of gestures, but as its own complex language.

Contribution by Natalia Estrada,

Reference and Collections Assistant, Social Sciences Division, The Library

Sources consulted:

- Jankowski, K. A. Deaf Empowerment: Emergence, Struggle, and Rhetoric. Washington, D.C: Gallaudet University Press, 1997.

- Long, J. S. The Sign Language; A Manual of Signs, Being A Descriptive Vocabulary of Signs Used by the Deaf of The United States and Canada (2nd ed. reprint). Washington: Gallaudet College, 1969 [©1952].

- Cockrell, Cathy. “ASL Language Courses a Sign of the Times at Berkeley,” Daily Californian (September 20, 2012).

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: The Sign Language; A Manual of Signs, Being A Descriptive Vocabulary of Signs Used by the Deaf of The United States and Canada

Author: Joseph Schuyler Long, 1869-1933.

Imprint: Washington, Gallaudet College, 1969 [©1952].

Edition: 2d ed., rev. and enl.

Language: American Sign Language

Language Family:

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Michigan)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001743786

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Spanish (Latin America)

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

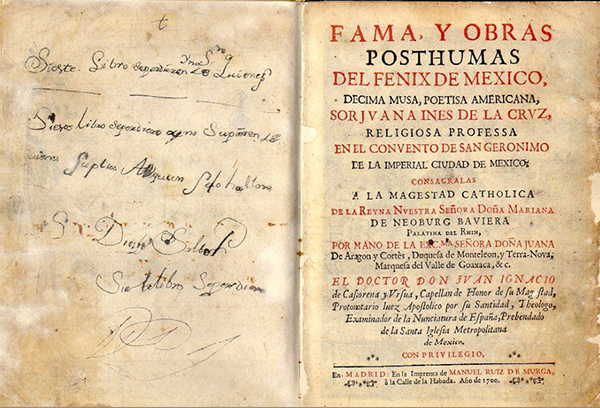

Nun, rebel, genius, poet, persecuted intellectual, and proto-feminist, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (Nepantla 1648-Mexico City 1695) was the most distinguished intellectual in the pre-Independence American colonies of Spain. She was called “Tenth Muse” in her own time and continues to inspire the popular and scholarly imagination. Generations of Mexican schoolchildren have memorized her satirical ballad “Hombres necios que acusáis / a la mujer sin razón… “ (You foolish men who cast all blame on women), and her portrait appears on the 200-peso note. Despite her status as an icon of Mexican culture, an annotated edition of her complete works was not published until the tercentenary of her birth in the mid-1950s, and the complexity of her poetry, prose, and theater was known only by reputation until the second wave of feminism brought scholarly attention to her work in the 1970s. Octavio Paz’s monumental study, Sor Juana, o, Las trampas de la fe (Sor Juana, or The Traps of Faith) appeared in 1982.

An intellectual prodigy brought to the viceregal court of New Spain in her teens, Sor Juana was largely self-taught. In 1669, she entered the convent of San Jerónimo in order to continue her studies. Although women were excluded from the study of theology and rhetoric, she wrote a brilliant critique of a renowned Portuguese cleric’s sermon, and was reprimanded by the Bishop of Puebla, who wrote under a female pseudonym. Sor Juana’s “Respuesta a sor Filotea” (1691, “Reply to Sister Philothea”) displayed her erudition in defense of her intellectual passion, arguing that St. Paul’s often-quoted admonition that women should keep silent in church (mulieres in ecclesia taceant), should not prohibit women’s pursuit of knowledge and instruction of young girls. Other significant works include secular and religious theater; philosophical poetry; passionate poems to the noblewomen who were her patrons; and villancicos, sets of songs she was commissioned to write for religious celebrations.

Sor Juana’s long epistemological poem, Primero sueño (First Dream) epitomizes the Creole appropriation of the Baroque and yet she weaves into her poetry and theater a recognition of the humanity of indigenous peoples. While her literary models were European and her poetry was first published in Spain, her works evince an American consciousness in the representation of the violence of the conquest in the loa to El divino Narciso (Divine Narcissus) and her use of Nahuatl in the villancicos.

Contribution by Emilie Bergmann

Professor, Department of Spanish & Portuguese

Title: Fama, y obras póstumas

Title in English: Homage and posthumous works

Author: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1648-1695)

Imprint: Madrid: Manuel Ruiz de Murga, 1700.

Edition: 1st

Language: Spanish (Latin America)

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Universitätsbibliothek, Universität Bielefeld

URL: http://ds.ub.uni-bielefeld.de/viewer/image/1592397/1

Other online editions:

- Inundación castálida, de la única poetisa, musa décima, soror Juana Inés de la Cruz … (Madrid: Juan García Infanzón, 1689) and the first edition of Segundo volumen de las obras de soror Juana Inés de la Cruz (Sevilla: Tomás López de Haro, 1692).

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Critical and annotated editions of the first two volumes of Sor Juana’s work, Inundación Castálida (1689) and Segundo tomo (1693), as well as Fama, y obras póstumas and editions of complete and selected works are available in printed form in The Bancroft Library and the Main Stacks.

- Sor Juana’s complete works were published in four volumes: Obras completas, Alfonso Méndez Plancarte and Alberto G. Salcedo. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1951-57. Many English translations of selected works of Sor Juana’s works are also in OskiCat including those of Alan S. Trueblood, Margaret Sayers Peden, Amanda Powell, and Edith Grossman.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)