Tag: “The Languages of Berkeley”

Yiddish

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

דער גרויסער וועלט-פּראָגרעס האָט זיך אַהין אַרייַנגעכאַפט און האָט איבערגעדרייט די שטאָט מיטן קאַָפּ אַראָפּ, מיט די פֿיס אַרויף.

The great progress of the world has reached Kasrilevke and turned it topsy-turvy.

– From narrator’s foreword to the Kasrilevke stories (1919)

אַיין אַיינשרומפּעניש! ווען האָט געקאָנט ארויס דער צאַפּען, אַיינגעזונקען זאָל ער ווערען? … אַ, ברענען זאָלסט דו, שלים־מזל, אויפ’ן פייער!

און גרונם … דערלאַנגט דעם אַ רוק מיט’ן בייטש־שטעקעל אין זייט אַריין. דאָס פערדעל טהוט אַ פּינטעל מיט די אויגען, לאָזט־אַראָפּ די מאָרדע, קוקט אָן אַ זייט און טראַכט זיךְ׃ פאַר וואָס קומט מיר, אַשטייגער, אָט דער זעץ? גלאַט גענומען און געבוכעט זיךְ! ס’איז ניט קיין קונץ נעמען אַ פערד, אַ שטומע צונג, און שלאָגען איהם אומזיסט און אומנישט!

The driver of the wagon with the water barrel was beside himself! “An empty barrel! … May my helper shrivel up! How could that plug, may it sink into the earth, have come out? May you burn up, wretch that you are!” The last remark was addressed to the little horse, as he struck it with the whip handle. The horse blinked, lowered its chin, and looked aside, thinking, “What have I done to deserve this whack? It’s no trick, you know, to hit a dumb animal for no reason whatsoever.”

– From the story “Fires”

Yiddish is the thousand-year-old language of European (Ashkenazic) Jews. Written from right to left in Hebrew characters, it is derived from German and includes many Hebraic and Slavic elements. It is used for everyday purposes as well as for a rich variety of religious and secular literature, ranging from medieval times to the 21st century. Most Yiddish users were annihilated during the Holocaust of World War II, yet the language continues to thrive in the United States, Israel, and Europe.

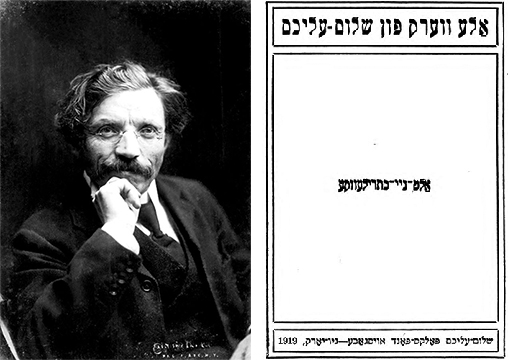

Arguably the best-known Yiddish writer, Sholem Aleichem (Sholem Rabinovich, Ukraine 1859 – United States 1916) was a founding father of modern Yiddish literature. A supreme humorist, he created the literary persona of “Sholem Aleichem” and tapped into the energies of the Eastern European spoken Yiddish idiom. In a variety of genres, he invented modern Jewish archetypes, myths, and fables of unique imaginative power and universal appeal. Sholem Aleichem’s “Tevye” stories provided the basis of the popular mid-20th century musical Fiddler on the Roof. He founded the Folks-bibliotek publishing house (Kiev, 1888) to encourage writers he admired, and identify new talent. In his satirical, yet warm Kasrilevke stories of the 1900s, he created the quintessential fictional shtetl. Its poverty-stricken residents aspired to modernity. Though plagued by backwardness, they continued to dream of redemption.

Following the death in 1916 of the beloved Sholem Aleichem, multi-volume editions of his collected works were published widely. This 1919 edition is printed in the Yiddish spelling prevalent at the time, with transliterations of Germanic linguistic elements; this was meant to help “legitimize” Yiddish (then considered a “jargon”). These transliterations are not used in modern standardized Yiddish orthography. The story “Fires,” from which this selection is taken, underlines the actual lack of progress in the fictional town of Kasrilevke, which prides itself on striving for modernity. The aside, giving voice to the abused horse in the midst of this municipal crisis, is typical of the creative yet plainspoken genius which made Sholem Aleichem so popular.

While the number of native speakers of Yiddish continues to dwindle, Yiddish at Berkeley is thriving. In addition to the esteemed annual conference on Yiddish Culture, we have a wide range of courses dealing with the life and culture of Ashkenazic Jewry, a diverse faculty committed to the preservation and scholarly investigation of Yiddish, and an ever-growing number of students who are pursuing academic futures exploring Jewish culture in the traditional languages of the Jewish people. Students interested in Yiddish at Cal can pursue their interests in the departments of German, Comparative Literature, History, or through the program in Jewish Studies.

Contribution by Yael Chaver

Lecturer in Yiddish, Department of German

Title: Alṭ-nay-Kas̀rileṿḳe

Title in English: Old-New Kasrilevke

Author: Sholem Aleichem, 1859-1916

Imprint: Nyu-Yorḳ : Shalom-ʻAlekhem folḳs-fond, 1919.

Edition: in Ale Verk, Sholom Aleichem

Language: Yiddish

Language Family: Indo-European, Germanic

Source: The Internet Archive (Yiddish Book Center)

URL: https://archive.org/stream/nybc200084

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Sholem, Aleichem. Alṭ-nay-kas̀rileṿḳe. Nyu-Yorḳ: Shalom-ʻAlekhem folḳs-fond, 1919.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Irish

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

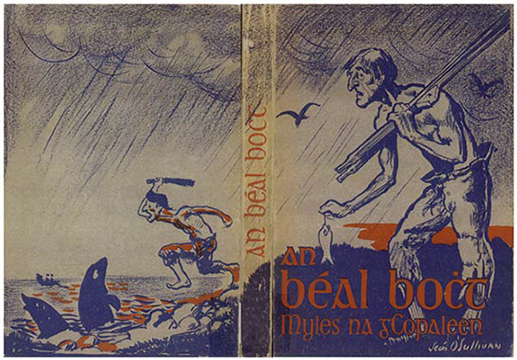

An Béal Bocht (1941), or The Poor Mouth, written by Brian O’Nolan (Ó Nualláin) under the pseudonym Myles na gCopaleen, is one of the most famous Irish language novels of the 20th century. O’Nolan, who most famously published works such as At-Swim-Two-Birds and The Third Policeman under the name Flann O’Brien, wrote in both English and Irish as a journalist and author.

O’Brien takes up the subject of the Irish Literary Revival, a movement in the early 20th century spearheaded by such figures as Lady Gregory and W.B. Yeats who tried to repopularize the Irish folklore and raise the ‘language question’ of Ireland. He simultaneously parodies the genre of Gaeltacht autobiography, autobiographies written in Gaelic that emphasize rural life in Ireland, such as An t-Oileánach (The Islandman) by Tomás Ó Criomhthain and Peig by Peig Sayers, and critiques aspects of the revival.

An Béal Bocht begins with the birth of the narrator, Bónapárt Ó Cúnasa, and follows his life in Corca Dorcha, an impoverished town in the west of Ireland. The town’s rurality attracts the elite from Dublin in search of ‘authentic’ Irishness. Corca Dorcha certainly fits the description — it never stops raining, it’s extremely remote, and crucially, everybody speaks only Irish. The large numbers of visitors from Dublin insist that they love the Irish language, and that one should always speak Irish, about Irish, but ultimately they find Corca Dorcha to be too poor, too rainy, and ironically, too Irish. The very authenticity they sought drives them away to bring their search for authenticity elsewhere.

An Béal Bocht is regarded as a masterful satire, deftly critiquing the genre, the Dublin elite who supposedly supported Irish language revival but avoided rural realities, and the state’s failure to maintain authentic Gaeltacht cultures. The title comes from the Irish expression — ‘putting on the poor mouth’ — which means to exaggerate the direness of one’s situation in order to gain time or favour from creditors. In the novel, there is also the repeated phrase, “for our likes will not be (seen) again,” taken directly from An t-Oileánach.

For more than a century, UC Berkeley has been a locus for the study of Irish culture, language, and literature. Faculty from the departments of English, Rhetoric, Linguistics, and History participate teach courses in Irish and Welsh language and literature (in all their historical phases), and in the history, mythology, and cultures of the Celtic world.[1] The Celtic Studies Program offers the only undergraduate degree in Celtic Studies in North America. Following a visit by President Michael Higgins in 2016 to foster relationships between Irish universities and UC Berkeley, the campus’s Institute of European Studies launched the Irish Studies Program.[2] Flann O’Brien’s works are taught in UC Berkeley classes such as Modern Irish Literature and the English Research Seminar: Flann O’Brien and Irish Literature.

Contribution by Taylor Follett

Literatures and Digital Humanities Assistant, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Celtic Studies Program, UC Berkeley (accessed 10/1/19)

- Irish Studies Program, Institute of European Studies, UC Berkeley (accessed 10/1/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: An Béal Bocht

Title in English: The Poor Mouth

Author: Myles, na gCopaleen (O’Brien, Flann, 1911-1966)

Imprint: Baile Áṫa Cliaṫ : An Press Náisiúnta, 1941.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Irish

Language Family: Indo-European, Celtic

Source: The Internet Archive (Mercier Press)

URL: https://archive.org/details/FlannOBrienAnBalBochtCs

Other online resources:

- Research guide to Flann O’Brien (UC Berkeley Library)

- Corpus of Electronic Texts (CELT)

- “Cruiskeen Lawn,” Myles na gCopaleen’s newspaper column in Irish Times (1859-2011) and Weekly Irish Times (1876-1958) via Proquest Historical Newspapers (UCB Only)

- Irish poet Louis de Paor speaking (in Irish) discusses An Béal Bocht,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vyIQI_huU9g.(accessed 6/18/19)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- O’Brien, Flann. An béal boċt: Nó, an milleánach : Droċ-sgéal ar an droċṡaoġal curta i n-eagar le. Dublin: Eagrán Dolmen, 1964.

- O’Brien, Flann. Translated into English by Patrick C. Power; illustrated by Ralph Steadman. The Poor Mouth: A Bad Story About the Hard Life. New York: Viking Press, 1974.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Vietnamese

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

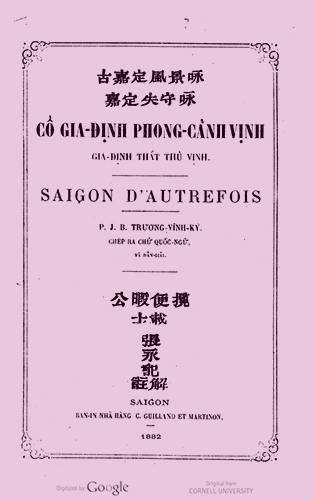

In the 17th century, French Catholic missionaries employed the Roman alphabet to devise a unique orthography for the Vietnamese language. This was the first time in world history that an alphabet represented distinctions in tone.[1] This specially developed Latin script or quốc ngữ, with its double diacritics, coexisted with hán nôm — the Vietnamese adaptation of Chinese script — for three centuries before triumphing under Colonial rule.[2] Scholar Trương Vĩnh Ký (Pétrus Ky) rewrote and annotated this rare work of poetry in romanized Vietnamese toward the end of the 19th century featured here in its original version of the “rhyme-prose” in hán nôm script. It describes many interesting landscapes and social life customs in Gia Dinh (Hồ Chí Minh City) today.

The Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies (SSEAS) at UC Berkeley offers both undergraduate and graduate instruction and research in the languages and civilizations of South and Southeast Asia from the most ancient period to the present. Instruction includes intensive training in several of the major languages of the area including Bengali, Burmese, Hindi, Khmer, Indonesian (Malay), Pali, Prakrit, Punjabi, Sanskrit (including Buddhist Sanskrit), Filipino (Tagalog), Tamil, Telugu, Thai, Tibetan, Urdu, and Vietnamese, and specialized training in the areas of literature, philosophy and religion, and general cross-disciplinary studies of the civilizations of South and Southeast Asia.[3] Outside of SSEAS beginning through advanced level courses are offered in Vietnamese, related courses are taught and dissertations produced across campus in Asian American Studies, Comparative Literature, Ethnic Studies, Folklore, French, History, Linguistics, and Political Science (re)examining the rich history and culture of Vietnam.[4] UC Berkeley’s Center for Southeast Asia Studies is also the editorial home of the Journal of Vietnamese Studies, published by the University of California Press.[5]

Contribution by Hanh Tran

Lecturer, Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies

Virginia Shih

Curator for the Southeast Asia Collection, South/Southeast Asia Library

Sources consulted:

- Garry, Jane, and Carl R. G. Rubino. Facts About the World’s Languages: An Encyclopedia of the World’s Major Languages, Past and Present. New York: H.W. Wilson, 2001.

- Dalby, Andrew. Dictionary of Languages: The Definitive Reference to More Than 400 Languages. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998.

- Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies, UC Berkeley (accessed 10/1/19)

- Vietnamese (VIETNMS) – Berkeley Academic Guide (accessed 10/1/19)

- Journal of Vietnamese Studies. Berkeley, CA. University of California Press, 2006-.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: C̉ô Gia-định phong-cảnh vịnh. Gia-định th́ât thủ vịnh. Saigon d’autrefois.

Title in English: [Saigon Bay Scene. Saigon of Old]

Author: Trương, P. J. B. Vĩnh Ký (Pétrus Jean-Baptiste Vĩnh Ký), 1837-1898.

Imprint: Saigon, C. Guilland et Martinon, 1882.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Vietnamese

Language Family: Austroasiatic, Mon-Khmer

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (Cornell University)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100620763

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Chichewa

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

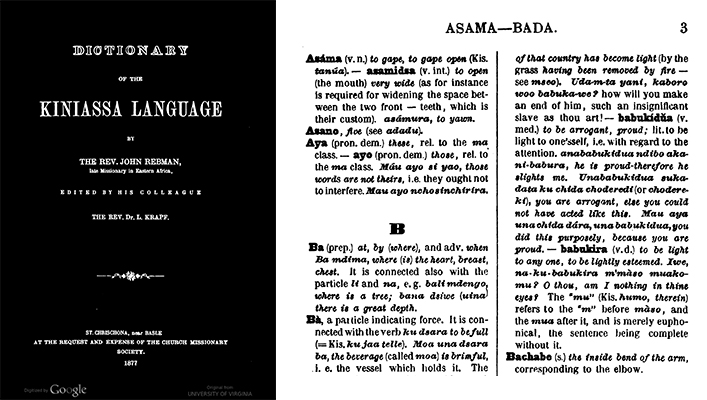

“My study of the Kiniassa was to me such a continual intellectual feast, that days and weeks fled so quickly as I never remembered they had done before, and it was with great reluctance that I tore myself from it when we had to get ready for our voyage to Aden.”

— Reverend John Rebman

With over 2,000 vernacular languages, sub-Saharan Africa includes approximately one-third of the world’s languages.[1] Many of these will likely disappear in the next hundred years, displaced by dominant regional languages like Chichewa. Also known as Chinyanja or Kiniassa, Chichewa is spoken in west-central and southwest Africa. In total, the language claims nearly 10 million speakers across the region. It is an official language — along with English — in Malawi and is officially recognized in Zambia and Mozambique where it is known as Nyanja. Chichewa is part of the Bantu branch of the larger Niger-Congo phylum. Linguistics and archaeologists suggest that these languages began in the grasslands of northwestern Cameroon and north-eastern Nigeria over two thousand years ago and spread across central and southern Africa through a combination of migration and conquest.[2]

The Dictionary of the Kiniassa Language, compiled by the reverend Johannes Rebmann brom 1853-54 and posthumously published in 1877, was the first extensive written record of the Chichewa language. It is representative of the fairly prolific publishing output of European missionaries — principally religious (bible translations, hymn books, etc.) or grammar and vocabulary texts — during the early colonial period.

These types of texts — especially the grammar and vocabulary texts — can offer a unique vantage point from which to view the imaginative nature of work that is otherwise often viewed as static. For example, in works of comparative religion, scholars can use these creative texts to gain insight into how missionaries grappled with words to accurately define religious concepts such as “sin” to serve their proselytizing purposes. Ultimately, old words were re-defined or altogether new words were crafted to meet the present need.

Contribution by Adam Clemons

Librarian for African and African American Studies, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Moseley, Christopher, and Alexandre Nicolas. Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. Paris: UNESCO, 2010.

- Dalby, Andrew. Dictionary of Languages: The Definitive Reference to More Than 400 Languages. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Dictionary of the Kiniassa Language

Author: Rebman, John, 1820-1876.

Imprint: St. Chrischona: Church Missionary Society, 1877.

Edition: 1st

Language: Chichewa

Language Family: Niger-Congo

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Virginia)

URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uva.x000079094

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Dictionary of the Kiniassa language, by the Rev. John Rebman, edited by his colleague, the Rev. Dr. L. Krapf. St. Chrischona, near Basle, Switzerland, The Church missionary society, 1877.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

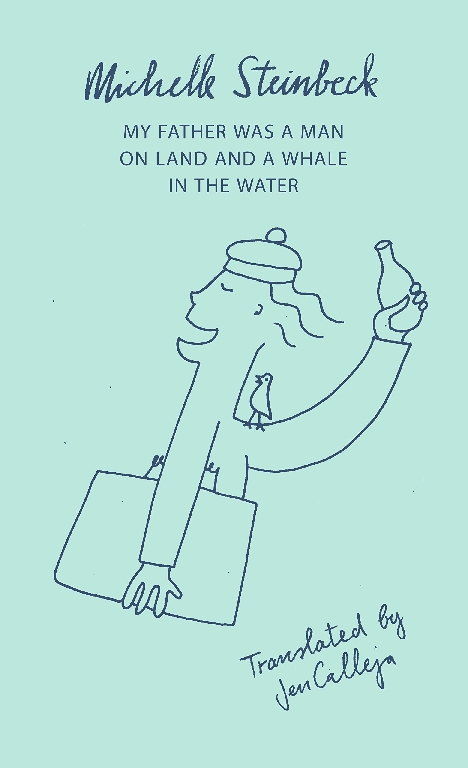

Book Talk with Michelle Steinbeck: My Father was a Man on Land and a Whale in the Water

Lecture | October 15 | 12-1 p.m. | 303 Doe Library

Michelle Steinbeck is a Swiss author, curator, and editor whose 2016 debut novel My Father was a Man on Land and a Whale in the Water (Mein Vater war ein Mann an Land und im Wasser ein Walfisch), published by Lenos Verlag, was nominated for both the Swiss and the German Book Prize. It has been described by one reviewer as “. . . one of the most audacious, exuberant and thrilling novels I’ve read for a long time, even if it is disturbing and bizarre. It is a modernist, magical mash-up about families, home, identity and, ultimately, happiness.”

Michelle will present this work, which has been translated into an English edition (2018, Darf Publishers), and also speak about her writing more broadly.

All Audiences

All Audiences

Arabic

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

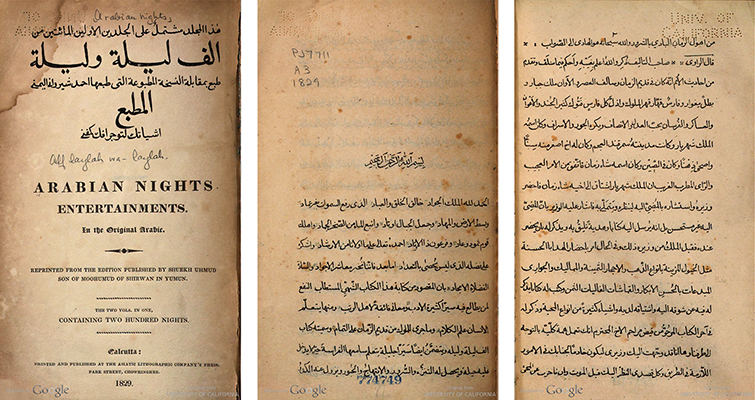

Arabian Nights or One Thousand and One Nights (Arabic: ألف ليلة وليلة, Alf Laylah wa-Laylah) is a multicultural collection of stories. According to The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia, “No other work of fiction of non-Western origin has had a greater impact on Western culture than the Arabian Nights.”[1] “[P]reserved in its Arabic compilation, the collection is rooted in a Persian prototype that existed before the ninth century CE, and some of its stories may date back even further to the Mesopotamian, ancient Indian, or ancient Egyptian cultures.”[2] This classic, like numerous other Arabic works, reveals the great influence of the Arabic legacy on other cultures.

The first Arabic manuscript of Arabian Nights dates back to the 15th century, which was first translated into French in 1704 by the French orientalist François Galland, followed by the English edition in 1706. Since then, Arabian Nights has been translated and reproduced in numerous languages and formats. Stories from Arabian Nights have also been represented in other art forms, such as drama and films to mention a few. Aladdin, The Thief of Bagdad, and Adventures of Sinbad are three examples of famous films.

Arabic became an essential language for human knowledge in the medieval centuries during the bright period of the Islamic civilization, when Muslim scholars vastly contributed to knowledge and science in many fields: algebra, geography, medicine, social sciences, astronomy and many more.[3] The impact of the Arabic language and Muslim scholars’ contribution is seen until today in different disciplines and, most definitely, in languages worldwide. In English, for instance, algebra, chemistry, and algorithm are originally Arabic words.

As the native language in more than 20 Arab nations and one of the official languages in many other countries, Arabic is one of the most spoken languages in the world after Chinese, Spanish, and English; hence, it is one of the six languages recognized by the United Nations. Arabic is one of the Semitic languages which, like Hebrew, are written from right to left. Most importantly, Arabic is the language of the Quran, the holy book of Islam. Therefore, it is the language of daily prayers around the world regardless of the Muslims’ native languages.

According to the Modern Language Association’s enrollment data for 2016, Arabic is among the top 10 languages taught in the US with 31,554 enrollments in 2016 compared to 24,010 enrollments in 2006.[4] This number includes students enrolled in classes for standard Arabic, as well as the Arabic language classes focusing on various dialects such as Egyptian colloquial Arabic, Shami (Syrian, Lebanese, and Palestinian/Jordanian) colloquial Arabic, Moroccan and North African colloquial Arabic, and Khaliji Arabic in the Persian Gulf Region.

At UC Berkeley, Arabic is one of the languages of emphasis for the major in Near Eastern Languages and Literature offered by the Department of Near Eastern Studies (NES). Students who major and minor in Arabic learn about the peoples, cultures, and histories of the Arabic speaking world besides the language. NES offers all levels of Arabic language courses: 1A and 1B (elementary), 20A, 20B and 30 (intermediate), and 100A and 100B (advanced), and an intensive summer program. Upper division courses range from the study of colloquial Arabic, to classical prose and poetry, to historical, religious and philosophical texts, to survey of and seminars in both classical and modern Arabic literature.[5]

Contribution by Mohamed Hamed

Middle Eastern & Near Eastern Studies Librarian, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Leeuwen, R. van, Marzolph, U., & Wassouf, H. (2004). Introduction. In The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia (p. xxiii). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

- Ibid.

- Ignacio Ferrando. ‘History of Arabic’ in Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Ed. Lutz Edzard et al. Brill Reference Online, 2019. (accessed 9/27/19)

- Modern Language Association of America. Enrollments in Languages Other Than English in United States Institutions of Higher Education, Summer 2016 and Fall 2016: Final Report (June 2019). (accessed 9/27/19)

- Arabic (ARABIC) – Berkeley Academic Guide (accessed 9/27/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Alf laylah wa-laylah

Title in English: Arabian Nights

Author: unknown

Imprint: Calcutta : The Asiatic Lithographic Company, 1829.

Edition: n/a

Language: Arabic

Language Family: Central Semitic

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (UC Berkeley)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100639014

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Spanish (Europe)

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

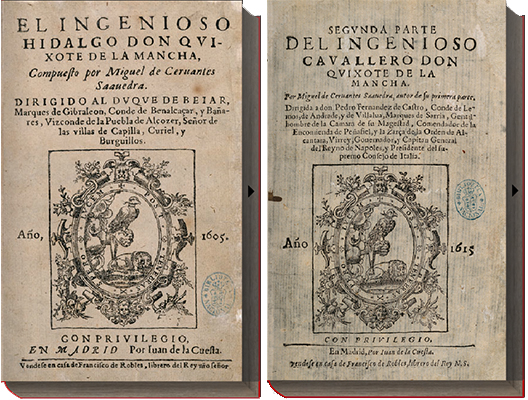

If you walk down the street in many parts of the world and ask a stranger who fought the windmills, they would most probably answer Don Quixote. But they would not necessarily know the name of its author, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1547-1616). This not-so-prolific dramaturge, poet and novelist has nonetheless had a major impact on the development of Western literature, influencing his English contemporary William Shakespeare, 19th-century French author Gustave Flaubert, and 20th-century Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges, just to name a few.

Cervantes did not come to prominence until much later in his life. His experiences as a soldier, a captive and a witness to the struggles of the Spanish empire shaped his distinctive oeuvre: a literary world of experimentation, as can be seen in his Exemplary Novels (1613), a world in which possibilities of reconciliation between conflictive individuals, ideals and desires remained hollow, inconclusive and, in many cases, without avail. Among other factors, what distinguishes Cervantes’ literary production is its unclassifiable nature, making it hard to try and fit the works in their presumed corresponding genre. One good example is his posthumous work The Travails of Persiles and Sigismunda (1616), where the Byzantine novel is mutilated to such an extent that, at points, it becomes almost unrecognizable.

Yet this unfittedness is most evident in Don Quixote (Part I published in 1605; Part II in 1615). The confusion between reality and fiction, the untrustworthiness of the multiple narrators, the intentional errors and misnomers, the three-dimensionalism of Don Quixote’s squire, Sancho, who has a love-hate relationship with his master, the utter destruction of the chivalric world, and the encounter with oppressed minorities are but some of the factors that have undoubtedly contributed to the sustained appeal of Don Quixote. The protagonist, an old man who “loses his mind” reading novels of chivalry, was, in Western literature, a pioneering self-proclaimed “hero.” He offers and imposes his help unto people who rarely take him seriously. Moreover, he only becomes popular, within his diegetic world, when in Part II he is defined by others as a caricature. This caricature remains dominant in the collective imaginary of readers, as can be seen, for example, in Picasso’s well-known depiction of the character.

Although most masterpieces ultimately attempt to challenge a comfortable experience of reading where we readily identify with fictitious characters; Don Quixote still manages to attract the empathy of its readers who may or may not closely identify with the knight-errant. Don Quixote is beaten up, both physically and metaphorically, yet his innocent, albeit selfish at times, intentions have ultimately won the hearts of a diverse audience over the centuries.

Today, the Spanish language, or Castilian as it is referred to in Europe, has grown from around 14 million speakers at the time of Cervantes to 477 million native speakers worldwide. It is now the second most used language for international communication and the most studied languages on the planet.[1] At Berkeley, Spanish is one of the most widely used languages for scholarship after English, particularly in departments such as Anthropology, Comparative Literature, Ethnic Studies, Film & Media, Gender & Women’s Studies, History, Linguistics, Political Science, and Rhetoric. Interdisciplinary graduate programs in Latin American Studies, Medieval Studies, Romance Languages and Literature, and Medieval and Early Modern Studies also require reading of original texts in Spanish.

Nasser Meerkhan, Assistant Professor

Department of Near Eastern Studies & Department of Spanish & Portuguese

Source consulted:

- Elias, D. José Antonio. Atlas historico, geográfico y estadístico de España y sus posesiones de ultramar. Barcelona : Imprenta Hispana, 1848; Hernández Sánchez Barbara, Mario. “La población hispanoamericana y su distribución social en el siglo XVIII,” Revista de estudios políticos, no.78 (1954); López, Morales H, and El español: una lengua viva. Informe 2017. Madrid : Arco Libros, S.L. : El Instituto, 2017.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha

Author: Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de, 1547-1616.

Imprint: En Madrid : por Iuan de la Cuesta, 1605, 1615.

Edition: 1st

Language: Spanish (Europe)

Language Family: Indo-European

Source: Biblioteca Nacional de España

URL: http://quijote.bne.es/libro.html (requires Flash)

Other online editions:

- El ingenioso hidalgo don Quixote de la Mancha / compuesto por Miguel de Ceruantes Saauedra. En Madrid : por Iuan de la Cuesta, 1605.

- Segunda parte del ingenioso cauallero don Quixote de la Mancha / por Miguel de Ceruantes Saauedra, autor de su primera parte. En Madrid : por Iuan de la Cuesta, 1615.

- The History of Don Quixote. Translated into English by J.W. Clark. Illustrated by Gustave Doré. New York, P.F. Collier, 1871 .

Select print editions at Berkeley:

Considered to be the most translated work every written, the Library has editions in French, German, Hebrew, Armenian, Quechua, and more. The earliest and best illustrated editions reside in The Bancroft Library.

- El ingenioso hidalgo don Quixote de la Mancha. Burgaillos. Published Impresso con licencia, en Valencia : En casa de Pedro Patricio Mey : A costa de Iusepe Ferrer mercader de libros, delante la Diputacion, 1605.

- Segunda parte del ingenioso cauallero don Quixote de la Mancha. En Valencia : En casa de Pedro Patricio Mey, junto a San Martin : A costa de Roque Sonzonio mercader de libros, 1616.

- Vida y hechos del ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha. Nueva edicion, corregida y ilustrada con 32 differentes estampas muy donosas, y apropriadas à la materia. Amberes, Por Henrico y Cornelio Verdussen, 1719.

- El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha / por Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra ; obra adornada de 125 estampas litográficas y publicada por Masse y Decaen, impresore litógrafos y editores, callejon de Santa Clara no 8. México : Impreso por Ignacio Cumplido, calle de los Rebeldes num. 2, 1842.

- Don Quixote / Miguel de Cervantes ; a new translation by Edith Grossman ; introduction by Harold Bloom. New York : Ecco, c2003.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Nahuatl

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

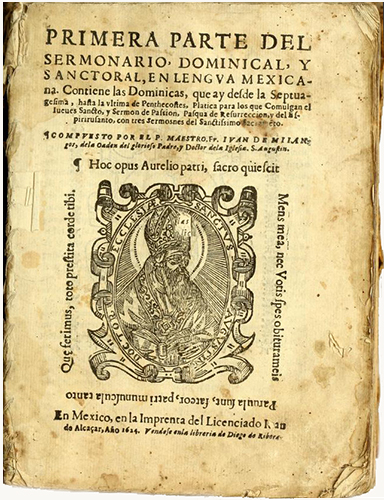

Written in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, the Primera parte del sermonario, dominical, y sanctoral, en lengua mexicana was published in Mexico City in 1624 at Juan de Alcázar’s printing press. The title of this collection of sermons is representative of the early colonial printing in Mexico City as well as the Augustinian order’s testament to the proselytizing efforts of the Catholic Church in Mexico. Only the first part of this Nahuatl text was ever published. Its author, Fr. Juan de Mijangos, is also well known for his Espejo Divino (1607).

As noted by Hortensia Calvo, director of the Latin American Library at Tulane University, Spain’s ideological, political and administrative control was possible with the early colonial press: “The first presses were brought to Mexico City and Lima for the explicit purpose of aiding missionaries in the Christianization of the native population.”[1] However, in the 17th century, following the Conquest, the Spanish occupiers dealt with many different populations of the region, hence many books were printed in the indigenous languages and, most importantly, not all texts were created for colonial or religious purposes. James Lockhart shows that, as early as 1545, the Nahuas of central Mexico adopted the Latin alphabet for their own purposes, beyond the interests of the colonial authorities and missionaries.[2] Indeed, former Berkeley professor José Rabasa argues that the “Alphabetical writing does not belong to rulers; it also circulates in the mode of a savage literacy. Bearing no trace of Spanish intervention in its production, the Historia de Tlatelolco exemplifies a form of grassroots literacy in which indigenous writers operated outside the circuits controlled by missionaries, encomenderos, Indian judges and governors, or lay officers of the crown.”[3] Several such texts have been digitized by the French National Library, including the Diario de Don Domingo de San Anton Muñón Chimalpáhin Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin (1579-1660).

Nevertheless, Marina Garone Gravier notes “there was a lack of in-depth knowledge of Nahuatl by some who composed these early sermons related books.”[4] Since the foundation of the Aztec Empire in 1325, Nahuatl played an essential role in daily workings. Published 103 years after the fall of the Aztec in 1521, the sermon book featured here evinces the continuation of Nahuatl during the early days of the Spanish Empire. Frances Kartunnen points out: “At the time of Spanish Conquest of Mexico [Nahuatl] was the dominant language of Mesoamerica, and Spanish friars immediately set about learning it. Some of them made heroic efforts to preach in Nahuatl and to hear confession in the language. To aid in these endeavors, they devised an orthography based on Spanish conventions and composed Nahuatl language breviaries, confessional guides, and collection of sermons, which were among the first books printed in the New World. Nahuatl speakers were taught to read and write their language, and under Friars’ direction the surviving guardians of an oral tradition set down in writing particulars of their shattered culture in the Florentine Codex and other ethnographic collections of Fray Bernardino de Sahagún and his contemporaries.”[5]

Today there are over one million Nahuatl speakers in Mexico and in the diasporic communities in the United States.[6] Yet, there are several dozens of Nahuatl dialects and, since this non-Romance language adopted the Latin Alphabet, it is difficult to apply standard orthographic principles to all of them.[7] Nonetheless, the following are essential textbooks for the teaching and learning of standardized Nahuatl: Richard Andrew’s Introduction to Classical Nahuatl, James Lockhart’s Nahuatl as Written, Michel Launey’s An Introduction to Classical Nahuatl and, for more advanced students, James Lockhart’s edition of Horacio Carochi’s Grammar of the Mexican Language.[8] Many other resources are available in print and digital format; for example, the University of Oregon’s online Nahuatl Dictionary, Molina’s bilingual dictionary Vocabulario en lengua castellana y mexicana (1571), UNAM’s online Gran Diccionario Náhuatl, and the app Vamos a aprender náhuatl.

Nahuatl language courses are available through UCLA’s distance learning program[9] and University of Utah’s Intensive Nahuatl Language and Culture Summer Program in Salt Lake City. The latter program, previously sponsored at Yale, has prepared many contemporary US-based Nahuatl scholars.[10] At UC Berkeley, the Joseph A. Myers Center for Research on Native American Issues has offered annual Nahuatl workshops,[11] and The Bancroft Library holds over 460 items, including the Primera parte del sermonario, dominical, y sanctoral, en lengua mexicana, concerning the Nahuatl language in its renowned Latin Americana Collection.[12]

The librarian for the Caribbean and Latin American Studies has requested this post to be published on September 16, 2019, which is is celebrated as the day of Independence in Mexico.

Contribution by Lilahdar Pendse

Librarian for Latin American Studies, Doe Library

Carlos Macías Prieto

PhD student, Department of Spanish & Portuguese

Sources consulted:

- Calvo, Hortensia. “The Politics of Print: The Historiography of the Book in Early Spanish America.” Book History, vol. 6, 2003, pp. 277–305. JSTOR.

- Lockhart, James. The Nahuas After the Conquest: A Social and Cultural History of the Indians of Central Mexico, Sixteenth Through Eighteenth Centuries. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996.

- Rabasa, José. Writing Violence on the Northern Frontier: The Historiography of Sixteenth-Century New Mexico and the Legacy of Conquest. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2000.

- Gravier, Marina Garone. “La tipografía y las lenguas indígenas: estrategias editoriales en la Nueva España.” La Bibliofilía, vol. 113, no. 3, 2011, pp. 355–374. JSTOR.

- Karttunen, Frances. An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl. Norman: Univ. of Oklahoma Press, 1992.

- Janick, Jules, and Arthur O. Tucker. Unraveling the Voynich Codex. Cham Springer , 2018.

- Andrews, J R. Introduction to Classical Nahuatl. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2003.

- Introduction to Nahuatl, Center for Latin American Studies, Stanford (accessed 9/12/19)

- Distance Learning Language Classes, UCLA (accessed 9/12/19)

- Beginners and Advanced Nahuatl Language and Culture Workshops, UCB (accessed 9/12/19)

- Utah Nahuatl Language and Culture Program (accessed 6/18/19)

- Latin Americana: Mexico and Central America, The Bancroft Library, UCB (accessed 9/12/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Primera parte del sermonario, dominical, y sanctoral, en lengua mexicana : contiene las Dominicas, que ay desde la Septuagesima, hasta la vltima de Penthecostes, platica para los que comulgan el iueues sancto, y Sermon de Passion, pasqua de Resurreccion, y del Espiritusanto, con tres sermosnes [sic] del sanctissimo sacrame[n]to / compuesto por el P. maestro Fr. Iuan de Miiangos, de la Oaden [sic] del glorioso Padre, y Doctor dela Iglesia. S. Augustin. (1624).

Author: Mijangos, Juan de, d. ca. 1625

Imprint: En Mexico : En la imprenta del licenciado Iuan de Alcaçar : Vendese en la libreria de Diego de Ribera : año 1624.

Edition: 1st

Language: Nahuatl

Language Family: Uto-Aztecan

Source: The Internet Archive (John Carter Brown Library)

URL: https://archive.org/details/primerapartedels00mija

Other Nahuatl texts online:

- Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin (1579-1660). Diario de Don Domingo de San Anton Muñón Chimalpáhin, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- Fray Bernardino de Sahagún (1499–1590). Historia general de las cosas de nueva España (The Florentine Codex). World Digital Library (Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana).

- Gran Diccionario Náhuatl [online]. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México [Ciudad Universitaria, México D.F.]: 2012.

- Molina, Alonso de, d. 1585. Vocabulario en lengua Castellana y Mexicana. En Mexico : en casa de Antonio de Spinosa, 1571.

- Online Nahuatl Dictionary (University of Oregon)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- The Bancroft Library has in its collection one of eight surviving copies of Primera parte del sermonario, dominical, y sanctoral, en lengua mexicana (1624) held in U.S. libraries.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Universitas Linguarum

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Linguarum enim inscitia disciplinas universas aut exstinxit, aut depravavit…

For ignorance of languages either marred or abolished the world of learning….

—Erasmus, 1529, De pueris statim ac liberaliter instituendis. Opera I, 377

Berkeley’s celebration of languages in the Library could not come at a better moment. We are living in a time when many Americans are smugly self-satisfied about speaking English Only, when our government has waged an ugly war against immigrants, when linguistic and cultural otherness is too often construed as a threat, and when the world of learning is narrowing to a point where it may again be falling on unfortunate times.

The national trends are clear. A recent report from the Modern Language Association shows that 651 foreign language programs in American colleges and universities were lost between 2013 and 2016. And these are not all “less commonly taught” languages: according to the MLA report, during the 2013-16 period, net losses included 129 French programs, 118 Spanish programs, 86 German programs, and 56 Italian programs. Since 2009, overall foreign language enrollments have declined by 15.3 percent nationally. A recent Pew Research Center study showed that only 20% of American K-12 students study a foreign language (as compared to 92% in Europe).

Berkeley is not immune to decreases in language enrollments, but our programs remain unusually strong and have been staunchly supported by the Berkeley administration. In any given year, between 50 and 60 languages are taught on campus, and this remarkable breadth reflects the diversity of the State of California and the backgrounds and research interests of our students and faculty. California leads the nation in linguistic diversity: 42% of Californians speak a language other than English in their homes (as of 2016), and California has more than a hundred indigenous languages. Not surprisingly, this year’s incoming students speak more than 20 languages.

Globalization is ostensibly a strong impetus for language study — and it is in most parts of the world, where knowledge of English and other major languages is viewed as a fundamental necessity for participation in the global economy. However, in the U.S., it seems that globalization has had the opposite effect, leading many Americans to adopt a complacent attitude: why study other languages when so much of the world revolves around English?

Berkeley resists such complacency. We recognize that knowing other languages opens up fresh perspectives on the world, on our relationships with others, on our own language and culture, on the various disciplines we study, and on the problems we strive to solve. Indeed, so many of the challenges we face today are global in nature and can only be approached through the multiplicity of perspectives that come with international cooperation and collaboration. While English may allow for broad sharing of information, the reality is that we will never fully understand the nuances of other peoples’ perspectives if we don’t speak their language. Furthermore, because language, thought, and identity are so intimately intertwined, acquiring languages other than our mother tongue enriches our very being, allowing us to take on new identities, adopt new attitudes and beliefs, develop greater cognitive flexibility, and understand ourselves and our culture in a new light. Seeing the world through the lens of another language and culture also fosters empathy, which is essential to counter increasingly pervasive waves of ethno-nationalism.

Our university library reflects this awareness that languages nourish our imagination, enhance our creativity, and broaden and deepen our understanding of worlds past and present. More than one third of the 13 million volumes in UC Berkeley’s collection are in languages other than English. Remembering that the word university derives from the Latin universitas, signifying both universality and community, let us celebrate together the rich diversity of the Library’s holdings and of languages on the Berkeley campus.

Rick Kern,

Professor, Department of French

Director, Berkeley Language Center

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Khmer

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Khmer has a written history traceable to the 7th century. It is the language of the great culture that built the sacred capital of Angkor center of a powerful kingdom between the 9th and 15th centuries. Linguists find many similarities between structures of Khmer and of Thai, two unrelated languages that coexisted for many centuries, exchanging literary and cultural influences.

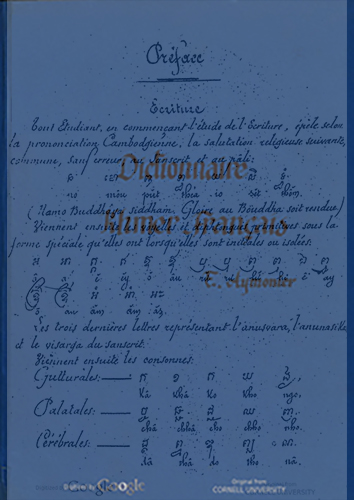

Aymonier’s Dictionnaire khmer-français, published in 1878, which expanded upon his earlier (1874), shorter, Vocabulaire cambodian-français, is probably the first dictionary of Khmer and a Western language with the Khmer entries (hand)written in Khmer script. The dictionary is also notable today for serving as a snapshot of Khmer orthography and vocabulary of the 19th century, as many of the entries in the dictionary are spelled very differently today, and in some cases, only in current use by speakers of Northern Khmer, which is largely spoken by the Khmer ethnic minority in Thailand.

The Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies (SSEAS) at UC Berkeley offers both undergraduate and graduate instruction and research in the languages and civilizations of South and Southeast Asia from the most ancient period to the present. Instruction includes intensive training in several of the major languages of the area including Bengali, Burmese, Hindi, Khmer, Indonesian (Malay), Pali, Prakrit, Punjabi, Sanskrit (including Buddhist Sanskrit), Filipino (Tagalog), Tamil, Telugu, Thai, Tibetan, Urdu, and Vietnamese, and specialized training in the areas of literature, philosophy and religion, and general cross-disciplinary studies of the civilizations of South and Southeast Asia. Outside of SSEAS where beginning through advanced level courses are offered in Khmer, related courses are taught and dissertations produced across campus in Art History, Comparative Literature, Folklore, History, Linguistics and Political Science (re)examining the rich history and culture of the Cambodia, or Kampuchea.

Contribution by Frank Smith, Lecturer

Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies

Sources consulted:

- Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies, UC Berkeley (accessed 8/28/19)

- Khmer (KHMER) – Berkeley Academic Guide (accessed 8/28/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Dictionnaire khmêr-français

Title in English: French-Khmer Dictionary

Author: Aymonier, E. (Etienne), 1844- compiler.

Imprint: Saigon : [s.n.], 1878.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Khmer

Language Family: Austroasiatic, Mon-Khmer

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (Cornell University)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100159918

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)