Tag: oral history center

Oral History Release – Thomas Gaehtgens: Famed Art Historian and Director of the Getty Research Institute

“As a scholar, one’s career typically revolves around teaching, research, and scholarship. Once in a while, a scholar is lucky enough to have a hand in building something. I’d like to think I have helped build a thing or two in my career.”

Such were the words of renowned art historian Thomas Gaehtgens upon wrapping up his oral history at the Getty Research Institute (GRI) in the fall of 2017. That the words held an element of retirement was no coincidence. Gaehtgens had already enjoyed a long and successful academic career before assuming the directorship of the GRI in 2007, a position from which he would officially retire in the spring of 2018. True to form, Gaehtgens met retirement with the same productive stride that had underpinned his work throughout the previous five decades. Thus, after a fruitful delay, the Oral History Center and Getty Trust are pleased to announce the release of Thomas Gaehtgens: Fifty Years of Scholarship and Innovation in Art History, from the Free University in Berlin to the Getty Research Center.

Getty Research Center

For many in the academic and art world of Europe, Gaehtgens needs no introduction. Born in Leipzig, Germany, he completed his PhD in art history at the University of Bonn in 1966, and over the next forty years held professorships at the University of Göttingen and the Free University of Berlin. He is the author of nearly forty publications on French and German art, covering a wide range of topics and artists from the eighteenth to the twentieth century.

Scholarship aside, Gaehtgens also made a mark through his globalist approach to art, fostering relationships that bridged the divides between universities and museums, as well as those between nations. He organized the first major exhibition of American eighteenth and nineteenth century paintings in Germany, expanded the art history curriculum in Berlin to include non-Western areas, and founded the German Center for Art History in Paris. These efforts made him a natural fit for president of the Comité International d’Histoire de l’Art (CIHA), where he advanced initiatives such as the translation of art history literature and broadening the field of art history through international conferences.

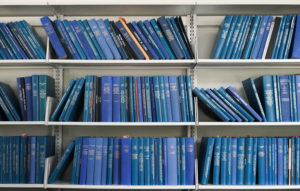

Gaehtgens brought this same spirit of inclusivity and innovation to the Getty Research Institute. In many respects, he helped usher the GRI into the twenty-first century by launching a number of programs that not only brought modern technology to the study of art, but also two principles close to Gaehtgens’ heart: international collaboration and equal access for all. The creation of the Getty Provenance Index proved a case in point. In partnership with a host of European institutions, the Index provided a one-stop, digital archive for researchers to trace the ownership of various art pieces over the centuries. Here, for the first time, the records of British, French, Dutch, German, Italian, and Spanish inventories stood at the fingertips of researchers. These same principles of technology, cooperation, and equitable access also underpinned the GRI’s creation of the Getty Research Portal, a free online platform providing access to an extensive collection of digitized art history texts, rare books, and related literature from around the world. Other important achievements of Gaehtgens’ directorship included the Getty Research Journal, a more internationally represented Getty Scholars program, and the Getty’s California-focused art exhibitions, Pacific Standard Time.

Thomas Gaehtgens retired from the Getty Research Institute in 2018, officially ending an art history career that spanned over fifty years. Fittingly, his decades of work have been recognized around the world. He holds honorary doctorates from London’s Courtauld Institute of Art and Paris-Sorbonne University. In 2009, he received the Grand Prix de la Francophonie by the Académie française, an honor bestowed by the Canadian Government to those who contribute to the development of the French language throughout the world. And in 2011, Gaehtgens was elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Such honors highlight the indelible mark he left on the global field of art history, one still seen today from the German Center for Art History in Paris to the now-famed digital programs of the Getty Research Institute. Indeed, Thomas Gaehtgens was not just an influential teacher and productive scholar, but also an innovative art historian who helped build a thing or two.

You can access the full oral history transcript of Thomas Gaehtgens here. See also other oral histories from the Getty Trust Oral History Project.

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library has interviews on just about every topic imaginable. You can find the interview mentioned here and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria. We preserve voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public.

Sign up for our monthly newsletter featuring think pieces, new releases, podcasts, Q&As, and everything oral history. Access the most recent articles from our home page or go straight to our blog home.

From the OHC Director: The Gift of Being an Interviewer

The Gift of Being an Interviewer

From years of listening, I’ve learned that we all want to tell our stories and that we want, we need, to be heard.

After close to nineteen years with the Oral History Center — ten of those years serving in a leadership role — I have decided to hang up my microphone and leave my job at Cal. As with any major life transition, reflections naturally pour forth at times like these. I’ve been keeping track of these thoughts in hopes that they might prove interesting to others who have spent so many hours interviewing people about their lives or those who are interested in oral history writ large.

For me, learning and practicing oral history interviewing has been a gift. It has made my life richer, allowed me to access insights about human nature that otherwise might have been hidden from me, and offered me the opportunity to see people as the individuals that they are, freed from the stifling confines of presumed identities and expected opinions.

At OHC, interviewers typically work on a wide variety of projects. We often interview about topics in which we do not already have expertise and thus must develop some fluency with something new to us. Because we contribute to an archive that is to serve the needs of an unforeseeable set of current and future researchers, we naturally interview people who have made their mark in very different fields. This means that we interview people, sometimes at tremendous length, who are not like us and whose life stories and ways of thinking might be very different from our own. There is a well-documented tendency among oral historians to interview our heroes, people whose political ideals jibe with our own, people who can serve protagonists in our histories, people whose voices we want to amplify. At the Oral History Center, this bias is not paramount — rather, we strive to interview people across a broad spectrum of every imaginable category. And while we almost always end up very much liking our interviewees, they need not be our personal heroes and are not required to share our opinions; they only need to be an expert in one thing: their own lives and experiences.

This way in which we do our work has sent me wide and far and exposed me to a profound diversity of ways of looking at the world. And this multiplicity of perspectives has informed, challenged, engaged, astounded, and, frankly, remade me again and again over the past two decades. It is this essential facet of my work that I consider a gift to my own life.

After having conducted approximately 200 oral histories, ranging in length from ninety minutes to over sixty hours each, I find it a tad difficult at this point to highlight some interviews and not others. Whenever I get asked (as I often do): what was your favorite interview? I used to wrack my brain, endlessly scrolling through all of those experiences, but now I usually just say, “my most recent oral history.” I offer that up because the latest one typically remains most fresh in my own (not always so robust) memory — it is the interview that still retains much of the nuance, content, and feeling for me and that’s why it is “the best.” Still, I want to offer up a few examples from some of my oral histories to show how interviewing has influenced the way I live in the world.

Moving beyond my comfort zone

I arrived at OHC in July 2003, first spending a year on a fellowship in which I was given the opportunity to finish my book manuscript, Contacts Desired (2006), and then in July 2004 I started as a staff interviewer. My areas of expertise were social history, the history of sexuality and gender, and the history of communications. My first major oral history assignment? A multiyear project on the history of the major integrated healthcare system, Kaiser Permanente. Not only was this topic well outside my area of expertise, it also was not intrinsically interesting to me. But this was a new job and a big opportunity, so with an imposing hill in front of me, I decided to climb it. The project went on for five years and during that time I conducted most of the four dozen interviews. The topics ranged from public policy and government regulation to epidemiological research and new approaches to care delivery. I was sensitive to my inexperience with the subject matter so I hit the books and consulted earlier oral histories. I worked hard to get up to speed.

Just a few interviews into the project I had what might be considered an epiphany. After years of studying historical topics that were familiar to me, even deeply personal, I was pleased to discover something new about myself: I loved the study of history and the process of learning something new. Period. With this newly understood drive, I pushed myself deeper into the project and, I hope, was able to be the kind of interviewer that allowed my interviewees to tell the stories that most needed to be told. As it happens, along the way, I learned a great deal about a topic — the US healthcare system — that is exceedingly important, extraordinarily complex, yet necessary to understand. When the push for healthcare reform burst through in 2009 and 2010, I felt informed enough to follow the story and to understand the possibilities and pitfalls endemic to such an effort. In short, if one is open to the challenge, oral history can significantly broaden one’s horizons, educating one in critical areas of knowledge (from the mouths of experts!), and it might even make one into a more informed citizen.

Questioning what I thought I already knew

The Freedom to Marry oral history project was in many ways the opposite of the Kaiser Permanente project. First off, I could rightfully consider myself an expert in the history of the fight to win the right to marry for same-sex couples and the broader issues surrounding it. After all, I had written a book on gay and lesbian history and had personal experience with the movement when I married my partner in February 2004. Moreover, in graduate school and in preparation for writing my book, I had closely studied the history of activism and social movements. I had gone into this project, then, thinking I had a pretty good idea of what the story would be and what the narrators might say on the topic: this would be another chapter in the decades-long fight for civil rights in which activists engaged in protest and direction action, spoke truth to power, and forced the recalcitrant and prejudiced to change their minds.

From fall 2015 through spring 2016, I conducted twenty-three interviews with movement leaders and big-name attorneys, but also with young organizers and social media pros; I interviewed people in San Francisco and New York, but also in Maine, Oklahoma, Minnesota, and Oregon. What I learned in these interviews not only made me greatly expand my understanding of the campaign for marriage equality, these interviews also forced me to revise my beliefs about social movements and how meaningful and lasting social change can happen (I write about this more here). As a result of this project, I came to believe that some forms of protest, especially violent direct action, are almost always counterproductive to the purported aims; that castigating people with different ideas and perceived values is wrong and likely to produce a long-term backlash; and that in spite of our differences of opinion on contemporary hot button social issues, the majority of people cherish similar core values — values that bind rather than separate. The interviews demonstrated that by focusing on the shared values, rather than hurling epithets like “homophobe!” or “racist!” at your opponents, the ground is better readied for future understanding to grow. The history I documented surely is more complex than this, but these observations are true to what I found and are a necessary part of the reason this particular movement succeeded as well as it did. Through the Freedom to Marry oral history project, I learned to question the accepted public narrative and even what historians think that they knew on a topic. I recognized that openness to new ideas is a prerequisite of good scholarship. I recognized that most of all I needed to listen to what the oral history interviewees said and to compare that to what I thought I already knew. As a result, I learned to not let what I thought I already knew determine what I could still learn.

Telling a good story

The oral history interview is a peculiar thing. As ubiquitous as interviewing seems today, from StoryCorps on NPR to countless podcasts featuring interviews around the world to articles in the biggest magazines, the classic oral history method as we practice it at OHC is still quite rare. For our interviews, both interviewer and interviewee put in a great deal of effort in terms of background research, drafting interview outlines, on-the-record interviewing (often in excess of 20 hours with one person), and review and editing of the interview transcript. As a result, our interviews are almost always excellent source material for historians, journalists, and researchers and students of all stripes. But what moves an oral history from “good documentation” to something more is often the quality of the storytelling. Certainly some people, as a result of special experiences, have more fascinating stories to tell than others, but everyone I’ve ever interviewed has many worthwhile stories to tell: from formative family dynamics while young to the universal process of aging.

The difference between a competently told story and an engrossing one isn’t necessarily the elements of the story but the skill and verve of the storyteller. To hear Richard Mooradian, for example, speak about his life as a tow truck driver on the Bay Bridge and tell what it’s like to tow a big rig on the bridge amidst a driving rain storm is, yes, to learn something new but, more, it is to gain insight into a personality and the passion that drives that person to do what he does. I eventually learned (maybe I’m still learning) that when someone begins a story — and I know now the difference between a question being answered and a story being told — it is time for me to shut up, actively listen, and be open to the interviewee to reveal something meaningful about themselves. After years of helping, I hope, others give the best telling of their own stories, I started to think about my own stories, both the stories themselves but also how they have been told. I’ve come to think that these stories are nothing less than life itself: they are the emotional diaries that we keep with us always and, if we’re good, are prepared to present them to friends and strangers alike. From years of listening, I’ve learned that most of us want to tell our stories and that we want, we need, to be heard. This is a deeply humane impulse and I like to think that nurturing this impulse is at the core of what I’ve learned to be of true value over the past two decades.

These three lessons — openness to moving beyond your comfort zone, questioning what you think you already know, and telling a good story — are not necessarily profound or new. For me, however, they are real and as I return to them regularly in my work and personal life, they have been transformative. They have been a gift. The world of knowledge is massive. Learning something new is a key part of this gift. I’ve long recognized that we live in a world of Weberian “iron cages,” siloed into separate tribes. Listening to my interviewees challenge accepted wisdom inspired me to buck trends, forget the metanarratives, and break free from those cages confining our intellect and spirit. Stories are the most precious things we can possess. Create many of your own and share them widely – and wildly. After close to nineteen years at the Oral History Center, I am departing to do just that: to focus on living new stories and ever striving to tell them better.

Martin Meeker

Oral History Center

Director (2016-2021)

Acting Associate Director (2012-2016)

Interviewer/Historian (2004-2012)

Postdoc (2003-2004)

Presenting the Oral History Center Class of 2020

At the conclusion of every academic year, the Oral History Center staff takes a moment to pause, reflect on the interviews completed over the previous year, and offer gratitude to those individuals who volunteered to be interviewed. The names below constitute the Oral History Class of 2020. Please join us in offering heartfelt thanks and congratulations for their contributions!

We would also like to take this time to thank our student employees, undergraduate research apprentices, and library interns. It was a unique semester, topping off a busy and productive year, and they continued to come through for us, as they always do. We rely on this team for work that is critical to our operations: research, interview support, and curriculum development; video editing; writing and editing of abstracts, front matter, and transcripts; and more. They’ve even produced articles and oral history performances to share our work with wider audiences. We couldn’t do it without them!

Find these and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page. You can search by name, key word, and several other criteria.

The Oral History Center Class of 2020

Individual Interviews

Robert L. Allen

Bruce Ames

Samuel Barondes

Alexis T. Bell

Robert Birgeneau

John Briscoe

Willie Brown

George Miller

Michael R. Peevey

Nancy Donnelly Praetzel

Robert Praetzel

John Prausnitz

Zack Wasserman

Bay Area Women in Politics

Mary Hughes

California State Archives

Jerry Brown

Chicano/a Studies

Vicki L. Ruiz

East Bay Regional Park District

Glenn Adams

Ron Batteate

Kathy Gleason

Raili Glenn

Brian Holt

Diane Lando

Mary Lentzner

John Lytle

Beverly Marshall

Rev. Diana McDaniel

Roy Peach

Janet Wright

Economist Life Stories

George Tolley

Getty Trust

Peter Bradley

Kathleen Dardes

David Driskell

Melvin Edwards

Charles Gaines

Kenneth Hamma

Thomas Kren

David Lamelas

Mark Leonard

Richard Mayhew

Howardena Pindell

Michael R. Schilling

Joyce Hill Stoner

Yvonne Szafran

Global Mining

Bob Kendrick

Napa Valley Vintners

David Duncan

Paula Kornell

David Pearson

Linda Reiff

Emma Swain

SF Opera

Kip Cranna

David Gockley

Sierra Club

Lawrence Downing

Aaron Mair

Anthony Ruckel

SLATE

Susan Griffin

Julianne Morris

Yale Agrarian Studies

Marvel “Kay” Mansfield

Alan Mikail

Paul Sabin

Ian Shapiro

Helen F. Siu

Elisabeth Jean Wood

Thank You

Student Employees

Max Afifi

Gurshaant Bassi

Yarelly Bonilla-Leon

Jordan Harris

Abigail Jaquez

Nidah Khalid

Ashley Sangyou Kim

Devin Lizardi

JD Mireles

Tasnima Naoshin

Lydia Qu

Lauren Sheehan-Clark

Librarian Interns

Jennifer Burkhard

Charissa Fitzpatrick

Undergraduate Research Apprentices

Corina (Mei) Chen

Nika Esmailizadeh

Evgenia Galstyan

Emily Keats

Esther Khan

Emily Lempko

Atmika Pai

Samantha Ready

Kendall Stevens

Episode 3 of the Oral History Center’s Special Season of the “Berkeley Remix” Podcast

Lately, things have been challenging and uncertain. We’re enduring an order to shelter-in-place, trying to read the news, but not too much, and prioritize self-care. Like many of you, we here at the Oral History Center are in need of some relief.

So, we’d like to provide you with some. Episodes in this series, which we’re calling “Coronavirus Relief,” may sound different from those we’ve produced in the past, that tell narrative stories drawing from our collection of oral histories. But like many of you, we, too, are in need of a break.

The Berkeley Remix, a podcast from the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. Founded in 1954, the Center records and preserves the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world.

We’ll be adding some new episodes in this Coronavirus Relief series with stories from the field, things that have been on our mind, interviews that have been helping us get through, and finding small moments of happiness.

Our third episode is from Amanda Tewes.

Greetings, everyone. This is Amanda Tewes.

As we are all still hunkering down at home, I wanted to share with you a few selections from Robert Putnam’s classic book, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Now, I can’t say that this book is a personal favorite of mine – in fact, it brings up some not-so-fun memories of cramming for my doctoral exams in American history – but it has been on my mind lately, especially in thinking about our shifting social obligations to one another in times of crisis, like the 1918 Influenza Epidemic or the heady days after 9/11.

Putnam published Bowling Alone in 2000, following decades of what he saw as degenerating American social connections, and much of the book reads like a lament of a changing American character.

In the context of our current moment, the following passages stood out to me:

……………………………………………………………………………………………………….

The Charity League of Dallas had met every Friday morning for fifty-seven years to sew, knit, and visit, but on April 30, 1999, they held their last meeting; the average age of the group had risen to eighty, the last new member had joined two years earlier, and president Pat Dilbeck said ruefully, “I feel like this is a sinking ship.” Precisely three days later and 1,200 miles to the northeast, the Vassar alumnae of Washington, D.C., closed down their fifty-first – and last – annual book sale. Even though they aimed to sell more than one hundred thousand books to benefit college scholarship in the 1999 event, co-chair Alix Myerson explained, the volunteers who ran the program “are in their sixties, seventies, and eighties. They’re dying, and they’re not replaceable.” Meanwhile, as Tewksbury Memorial High School (TMHS), just north of Boston, opened in the fall of 1999, forty brand-new royal blue uniforms newly purchased for the marching band remained in storage, since only four students signed up to play. Roger Whittlesey, TMHS band director, recalled that twenty years earlier the band numbered more than eighty, but participation had waned ever since. Somehow in the last several decades of the twentieth century all these community groups and tens of thousands like them across America began to fade.

It wasn’t so much that old members dropped out – at least not any more rapidly than age and the accidents of life had always meant. But community organizations were no longer continuously revitalized, as they had been in the past, by freshets of new members. Organizational leaders were flummoxed. For years they assumed that their problem must have local roots or at least that it was peculiar to their organization, so they commissioned dozens of studies to recommend reforms. The slowdown was puzzling because for as long as anyone could remember, membership rolls and activity lists had lengthened steadily.

In the 1960s, in fact, community groups across America had seemed to stand on the threshold of a new era of expanded involvement. Except for the civic drought induced by the Great Depression, their activity had shot up year after year, cultivated by assiduous civic gardeners and watered by increasing affluence and education. Each annual report registered rising membership. Churches and synagogues were packed, as more Americans worshipped together than only a few decades earlier, perhaps more than ever in American history.

Moreover, Americans seemed to have time on their hands. A 1958 study under the auspices of the newly inaugurated Center for the Study of Leisure at the University of Chicago fretted that “the most dangerous threat hanging over American society is the threat of leisure,” a startling claim in the decade in which the Soviets got the bomb. Life magazine echoed the warning about the new challenge of free time: “Americans now face a glut of leisure,” ran a headline in February 1964. “The task ahead: how to take life easy.” …

…For the first two-thirds of the twentieth century a powerful tide bore Americans into ever deeper engagement in the life of their communities, but a few decades ago – silently, without warning – that tide reversed and we were overtaken by a treacherous rip current. Without at first noticing, we have been pulled apart from one another and from our communities over the last third of the century.

Before October 29, 1997, John Lambert and Andy Boschma knew each other only through their local bowling league at the Ypsi-Arbor Lanes in Ypsilanti, Michigan. Lambert, a sixty-four-year-old retired employee of the University of Michigan hospital, had been on a kidney transplant waiting list for three years when Boschma, a thirty-three-year-old accountant, learned casually of Lambert’s need and unexpectedly approached him to offer to donate one of his own kidneys.

“Andy saw something in me that others didn’t,” said Lambert. “When we were in the hospital Andy said to me, ‘John, I really like you and have a lot of respect for you. I wouldn’t hesitate to do this all over again.’ I got choked up.” Boschma returned the feeling: “I obviously feel a kinship [with Lambert]. I cared about him before, but now I’m really rooting for him.” This moving story speaks for itself, but the photograph that accompanied this report in the Ann Arbor News reveals that in addition to their differences in profession and generation, Boschma is white and Lambert is African American. That they bowled together made all the difference. In small ways like this – and in larger ways, too – we Americans need to reconnect with one another. That is the simple argument of this book.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………….

There is a lot to find discouraging these days, but I actually have been heartened to see the ways in which Americans – and individuals the world over – have been committing and recommitting to each other and to their communities. Citing a “now more than ever” argument, folks are setting up local pop-up pantries with food, household supplies, and books; some are reaching out to their neighbors for the first time; and of course, we are practicing social distancing not just to keep ourselves safe, but also our communities.

Witnessing these acts, I have to wonder if Putnam’s argument about a decline in social obligations and connectivity was just one moment in American history and not a full picture. What will the historical narrative about this time be? Are we now experiencing a blip in social relations, or is this a great turning point? I’m hoping for the latter.

Stay safe, everyone. Until next time!

Dispatch from the OHC Director, April 2020

From the OHC Director, April 2020

I’ve been thinking a great deal of late about what it means to live a life connected or disconnected or perhaps something in between. I suspect I’m not alone in pondering these states of being — a kind of remote engagement that itself feels a little bit like connection.

Oral history is about many things: listening, documenting, questioning, recording, explaining. I think connection is always key to the work that we do as oral historians. But like many other operations, including basically all non-medical research projects that involve humans, our work conducting interviews is largely shut-down while we consider how best to forge ahead.

My colleagues and I have always valued the importance of the in-person, face-to-face interviewing experience. We regularly travel across the country at some considerable expense just so we can be in the same room with the person we are interviewing. We have found this time in close proximity with our narrators to be priceless. Not only does this allow us to shake hands, look eye-to-eye, and gauge body language just before and during the interview, but also these are practices that, until recently, have been second nature — we usually do them without thinking much about it. There really is an unconscious kind of dance that happens, especially when meeting someone for the first time, that in most instances results in a spontaneously choreographed fluidity that can carry the ensuring interview through fond memories and bad. Because of this, up to this point, only when it really was impossible to meet in person have we conducted an interview over the phone or online.

But times change. The current health crisis has profoundly rearranged social relationships, and likely for some time into the future. (Dr. Fauci even suggested that we rethink the practice of shaking hands, which, I’ll admit, makes me sad.) The Oral History Center staff have been scattered now for over a month. But we have endeavored to not lose touch with one another. Thanks to multifarious technological options, we have easily transitioned our weekly staff meetings online. We use either Google Hangouts or Zoom and, so far, everyone has used video, so we get to hear each other’s voices and see faces too. We sometimes have agenda items that require lengthy discussion, at other times we simply check in with each other about work but also about “how things are going.” We live in different settings so people have different challenges and we do our best to touch on those. I also chat every week with each of my colleagues individually and I’m very pleased to know that my colleagues have been meeting with each other, doing their best to push projects forward. The success of these virtual meetings, and, well, the zeitgeist, inspired me to set up virtual happy hours with friends and family. My family lives across the country and it’s been probably four years since we’ve been in the same room together but for the past two weeks we’ve all gathered online to check in, tell stories, have some laughs, get serious and, of course, get photobombed by various kids and dogs. We don’t escape the underlying gravity of the current situation, but this hasn’t stopped connection — in some real ways it has promoted it.

So, with this in mind, we are exploring the options for bringing our oral history back to life by bringing it online. We’re currently testing out various options for video and audio recording, paying close attention to everything from quality of recording to ease of use (considering that most people we interview don’t fit within the “digital native” demographic). We also are sensitive to the dimension of personal connection, rapport, and understanding, but given recent experiences “at” home and “in” the office, we have reason to be optimistic. The reasons for going online are not only about opportunity, they are much deeper and in some ways quite profound: every day, every month that passes, we lose an opportunity to interview someone who should have had the opportunity to tell their story. In fact, we just learned the very sad news that artist and advocate of Black artists, David Driskell, passed away due to complications from COVID-19. This was a man with a story to be told — and thankfully, with our partners at the Getty Trust, we conducted his oral history last year. We simply cannot wait out this epidemic and let it steal stories along with lives.

The second profound reason is related to something I’ve mentioned rather delicately here in the past: that the Oral History Center is a soft-money institution. What that means is we are basically a non-profit that earns its money (allowing us to do our work) by conducting interviews. The longer we are prevented from conducting oral histories, the more precarious our position becomes. We hope for but do not anticipate relief from the university, the state, or the federal government. All we want is to resume the good work of documenting our shared and individual experiences in times of growth and times of challenge — to continue the work that we’ve done for the past 66 years.

As we consider the path ahead, the Oral History Center staff continues to work vigorously albeit remotely. We’re finishing the production process on dozens of interviews that have been conducted already — that is, writing tables of contents, working with narrators on edits for accuracy and clarity, creating the final transcripts for bound volumes and open access on our websites. We continue to process original audio and video recordings so that they can be uploaded to our online oral history viewer. We’re writing blog posts about oral history and producing podcasts, including our newest and very topical season, Coronavirus Relief. Plus in addition to the regular work, we’re using this opportunity to focus on long desired projects: We’re creating curriculum for high schools; we’re writing abstracts for old interviews that never had them; and we’re using this time to think about new projects and write grant proposals so that when the time comes, we’ll be ready to go full steam ahead.

Check back here next month for more on our efforts to move oral history online. We’ll share our results publicly as many others are venturing into this domain too — and have themselves made important contributions to the conversation (I especially recommend checking out the free Baylor / OHA webinar on “Oral History at a Distance”). Until then, we sincerely hope that everyone this newsletter reaches stays safe, healthy, and able to remain connected to those who are important to you.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library

OHC Director’s Column – March 2020

From the Director — March 2020

From all of us at the Oral History Center, we are wishing you our best in these challenging times. We hope that you’re doing your best to get through the coming days, and above all, you and your loved ones are staying safe and healthy.

In a recent oral history, George Miller discussed the idea of the dreaded “Black Swan” event that might strike at a moment’s notice, leaving destruction and disruption in its wake. But Miller has artfully crafted a healthy sense of informed detachment and thus always used these events as an opportunity for learning and reflection. Perhaps the greatest lesson from the Black Swan events he experienced in the world of finance was that we always came out the other side — maybe a bit bruised but ready to face another day. So, as many of us sit at home, self-isolating, I invite you to take a break from the constant news feed of what is happening right now and instead spend some time in the past. Delve into the OHC archive of transcripts and recordings and expose yourself, for example, to many individuals who achieved great things in their lives but who each experienced Black Swan events of their own. Trial and turbulence, patience and perseverance.

Perhaps not surprisingly, many of the most remarkable of these stories come from women we’ve interviewed, in particular those women who broke glass ceilings in the workplace and the realm of politics. We’re currently developing a database documenting the hundreds of women we’ve interviewed over the years who were connected to the University of California — as part of the 150 Years of Women at Berkeley celebration. And we continue to contribute to this history with plenty of recent interviews, including female students who were active in the SLATE organization on campus in the 1950s and 60s. And then many more interviews with women who persevered while working in support of the arts (Kathleen Dardes), the environment (Michelle Perrault), and public service (Anne Halsted). You’ll see a handful of those stories referenced in this newsletter but I encourage you to just jump in, browse the collection (our Projects page is the best way to do this), and allow the thousands of life stories we’ve collected give you reassurance, perspective, and company.

Finally, we’ve made the decision to postpone our annual Oral History Commencement in which we invite our interviewees to campus for a lively celebration of oral histories completed in the past year. We still want to express our gratitude to our narrators, so stayed tuned.

Martin Meeker, Charles B. Faulhaber Director of the Oral History Center

OHC Director’s Column – January 2020

From the OHC Director:

The staff of the Oral History Center wishes everyone a happy and productive 2020!

After a long winter’s rest for the Berkeley band of oral historians, this year has jumped off to a running — and even wild — start.

For one, we have begun the unveiling of our lengthy life history interview with four-term California Governor Jerry Brown. Done in partnership with KQED Public Media, this oral history also serves as the first interview conducted for the relaunched California State Government Oral History Project, a project of the Secretary of State. Read more about the interview background and context — or the interview itself. Here’s the page that serves as clearing house for all information about and coverage of this important oral history

We are in the final phases of preparing a number of new interviews for release in the coming weeks and months, including new releases for our projects with: the Sierra Club, the East Bay Regional Park District, the Presidio Trust, San Francisco Opera, the founders of Chicano/a Studies, and the Getty Trust African American Artist project.

Along with our usual oral history work, we are preparing for our annual Introductory Workshop (Leap Day! February 29th) and Advanced Summer Institute (August 10–14). Applications for the Introductory Workshop and Advanced Institute are both now open.

Come back in February for a more substantive column from your’s truly. Until then, back to that reservoir of unread emails!

Martin Meeker, Oral History Center Director

#notoralhistory

by Shanna Farrell

@shanna_farrell

During the first few months that I was settling into life in the Bay Area after moving across the country, I often listened to WNYC, a New York City-based radio station. One morning, as I was riding my bike to work, the host of their call-in show, akin to KQED’s Forum, announced the upcoming segment.

“What was better back in the day?” the host asked. “It’s an oral history of nostalgia, starring you. Tell us about what you think was better from a previous era, why you miss it, and whether you think it’s better because of nostalgia, or because things were, empirically, better back in the day. Call us or post below.”

My heart started to race. This call out felt so personal. They had gotten it so wrong. I pulled over and dialed their number. A producer answered, unaware of their error.

“I just heard your next segment is on the oral history of nostalgia,” I said. “But that’s not oral history.”

Confused, she asked me to explain what I meant. It was October of 2013, and I was fresh off earning a Master’s Degree in Oral History. I had spent a year taking method and theory classes, learning about what defines the discipline, exploring its boundaries. I had my interviews critiqued, my questions workshopped, and had been pushed to dig deeper into my research, all in the name of preparation. This felt dismissive of the work that we oral historians put into our interviews. It devalued the time (and money) that I’d put into my degree, and the job that I had just landed at UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center.

As I tried to explain what oral history is and how what they were doing in this segment wasn’t it, I realized it would be impossible to fit into a two sentence elevator pitch. There’s so much that defines oral history, that makes it unique, distinct from other methods, that I could feel myself having trouble reducing it to something easy to pitch, just as they had to listeners.

Looking back on that moment, I wish I would have said that oral history is defined by the planning, the transparency, the collaboration, the recording, intersubjectivity, the preservation, the legacy. I wish I would have said that it could take weeks to carefully research and write an interview outline, hours to build rapport, and months to complete an interview series. I wish I would have said that it takes practice to craft questions and to listen in stereo, picking up on the things that aren’t said, and to be comfortable sitting in silence.

After I hung up the phone, I thought about why they called this segment “oral history.” I’m still thinking about it. The term became popular when magazines started running vox populi style interviews weaving together soundbites from different people to create a narrative. They ran pieces about the about the making of a movie, like Jurassic Park, or a TV show, like The Simpsons. Later, it became a household term when StoryCorps partnered with NPR to bring us our Friday driveway moments, produced from a carefully edited interview excerpt. Lately, it has seeped into literature. More and more, I see “oral history” to describe a work of memoir, creative nonfiction, and even fiction. Recently, I was reading the Sunday New York Times book review section and they positioned a new memoir as “part oral history, part urban history.” I couldn’t wrap my head around what this meant. How was it oral history? Had the author done interviews? How was this different from a regular memoir? And lately, I’ve seen a few journalists refer to themselves as oral historians without seeming like they have a solid understanding of what the term means, aside from it involving interviews.

Where does this lack of understanding stem from? Why is the term “oral history” battered around so easily? When did it first get misappropriated? The origin of the Entertainment Weekly and Vanity Fair versions are relatively straightforward, descending from the Jean Stein-style books like Edie: American Biography, which is constructed from interviews with people who knew Edie Sedgwick after her death in 1971, or books that recounted musical eras, like We Got the Neutron Bomb by Mark Spitz and Brendan Mullen (which also served as my first introduction to oral history when I was in high school) or Please Kill Me by Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain. As for where the rest of it came from – like the recent trend in literature – it’s anyone’s guess.

I’m not the only one who has been noticing this trend. In 2014, the anonymous user @notoralhistory joined Twitter. For a while, they tweeted examples of people labeling articles or projects as oral history that were, indeed, not actually oral history. They now promote examples of oral history and engage in conversations around best practices. There are practitioners who also tweet bad examples of oral history, using #notoralhistory, which are often amusing, and then maddening, and then amusing again.

The problem with these mediums is that they can’t accomplish the same things that actual oral history does. These narratives just provide soundbites, while oral history gives us much more context. They don’t include any audio (or video), so we lose the ability to connect with a human voice. They are highly edited, whereas oral history allows people to speak in their own style. They are usually layered with other voices, instead of giving someone individual space to fully narrate their own story.

The link in @notoralhistory’s bio takes you to the Oral History Association’s website, to the page where they define oral history. Here, they share a quote from Donald Ritchie’s book, Doing Oral History. He writes:

“Oral History collects memories and personal commentaries of historical significance through recorded interviews. An oral history interview generally consists of a well-prepared interviewer questioning an interviewee and recording their exchange in audio or video format. Recordings of the interviews are transcribed, summarized, or indexed and then placed in a library or archives. These interviews may be used for research or excerpted in a publication, radio or video documentary, museum exhibition, dramatization or other form of public presentation. Recordings, transcripts, catalogs, photographs and related documentary materials can also be posted on the Internet. Oral history does not include random taping, such as President Richard Nixon’s surreptitious recording of his White House conversations, nor does it refer to recorded speeches, wiretapping, personal diaries on tape, or other sound recordings that lack the dialogue between interviewer and interviewee.”

Oral history can accomplish so much. It gives us insight into the past, hearing directly from the people who lived through various moments in history. By archiving the recordings, we can listen to how narrators tell their stories, and gain insight into why they told it this way. We can put a human face on history and learn from those who came before us. And, when oral history is done right, through careful preparation, research, and recording, we can ensure that these people are not forgotten, their stories not reduced to a soundbite.

It is with similar intention that we are devoting many of our articles this month that revolve around the boundaries of oral history. You’ll hear from us about our experience doing oral history and what makes it different from other disciplines and methods. We hope you follow along.

Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project

This project is unique in that it focuses on women in one geographic region in order to get a clearer picture of the breadth of political work women have been doing on the ground and behind the scenes.

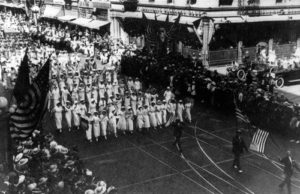

Nineteen ninety-two has been dubbed “The Year of the Woman,” a phenomenon in which a wave of women candidates swept local and national races for public office. California led this charge by becoming the first state in American history to be represented by two women senators—Barbara Boxer and Dianne Feinstein. And since 2016—after a presidential election that provoked heated debate about gender discrimination and sexual harassment—many women stepped up to the challenge of engaging even more visibly in the American political system. Since then, organizations like Emily’s List and She Should Run reported record-breaking numbers of women who wanted to make their voices heard by running for public office.

And yet, 1992 was not the beginning of women’s political activism, but rather the culmination of decades of organization encouraging women to get involved and run for office. For generations, Bay Area women have built the foundations of political activism that span neighborhood organizations to support networks. And their stories inform our present.

In order to document these stories, I am developing the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project to record the history of these local women and their impact on and journeys through politics. The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley continues to preserve stories about California politicians, but this project is unique in that it focuses on women in one geographic region in order to get a clearer picture of the breadth of political work women have been doing on the ground and behind the scenes. Documenting political engagement outside of traditional political venues will capture more stories about women in politics and a more diverse array of stories.

For instance, the pilot interview for this oral history project is with Mary Hughes, a Bay Area political consultant. In her interview, Hughes explained that “in politics and in political consulting, you either win races or you don’t. If you don’t win, no one hires you. If you do win, everybody wants to hire you.” Hughes’s successful career in the Bay Area spans decades and highlights the prominence of women in national politics. And though she does not wish to run for office herself, Hughes sees her role as someone who can best serve her community by managing the election process for political candidates—especially other women. Hughes’s recollections are an example of the kinds of stories that will drive this oral history project.

These long-form oral history interviews survey Bay Area political women’s backgrounds in and passion for political work through self-reflection. This format allows for comparisons between various avenues of political activism—like organizers and elected officials. It also reveals the importance of networks and mentors, and the impact they have had on women in the Bay Area political scene.

As engaged citizens, we need to know more about these women who helped create a space for themselves in Bay Area political life. Who are these women and what are their stories? From neighborhood organizations to national campaigns, what is the range of political activism in which these women engage? How has being a woman been a challenge or an asset to their political involvement? How have these women been working in the background of political life for generations? How does living and working in California affect political opportunities? What kind of political power do these women wield locally and nationally?

As we approach the hundredth anniversary of women’s suffrage, conducting oral histories with women activists and politicians in California’s San Francisco Bay Area will help shape the national narrative about women’s historic, current, and future roles in American political life. Further, gathering firsthand stories will help inspire and instruct a new generation of politically engaged women.

In addition to collecting primary source materials, The Oral History Center shares its collection with the general public through interpretive materials—like podcasts—and educational initiatives. Recording the contributions of these impressive Bay Area women—political fundraisers, organizers, and elected officials—through life history interviews is the first step in developing curriculum for workshops that cultivate young women’s political leadership. These workshops will use oral histories as a tool to foster civic engagement across the political spectrum, as well as to help develop confidence and skills of future women leaders. We also plan to create a podcast, a series of public forums, and a museum exhibit featuring these interviews.

We are currently raising funds for this project, and need your help to undertake the expansion of this ambitious oral history collection. You can support this project by giving to the Oral History Center. Please note under special instructions: “For the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project.” To learn more about this project, please contact Amanda Tewes at atewes@berkeley.edu or 510-666-3687.

Amanda Tewes is an interviewer with The Oral History Center and specializes in California history and political culture.

The Oral History Center is a research program of the University of California, Berkeley. The OHC helps preserve contemporary history by conducting carefully researched video recorded and transcribed interviews. As part of UC Berkeley’s commitment to open access, archival copies of the audio/video and transcripts are placed in The Bancroft Library and are publicly accessible online.

The Science and Art of Oral History: My Internship Experience

Eleanor Naiman is a rising senior at Swarthmore College majoring in History. This past summer, Eleanor worked with historian Amanda Tewes of the Oral History Center on the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project. As an intern, Eleanor researched the contributions of women to Bay Area politics and assisted Tewes with her interviews. Here, Eleanor reflects on her internship experience in the Oral History Center.

Eleanor Naiman, 2019

There is a science to professional oral history. From start to finish, the interview process requires meticulous attention to detail and respect for technique, form, and skill. When an OHC historian sets off to conduct an interview, be it a conversation with a Bay Area political consultant or with a Connecticut anthropologist, she does so equipped with heavy black bags of tools and folders and parts that, to the untrained (read: intern) eye, might seem better suited for the high-tech activities of a secret agent than the practice of oral history. And yet, each cord, mic, form, and gadget plays an integral role in the interview process.

Over the course of my summer as an intern at the OHC, I’ve become better versed in this highly technical science of capturing a story. I’ve learned how to identify a potential narrator and with which forms to ask for her consent. I’ve spent long hours researching the entirety of her life, creating an outline of its twists and turns and of the people with whom it has come into contact. I’ve become a convert to the practice of the “pre-interview,” a conversation that allows the interviewer to check her facts and flesh out her timeline.

Even the intimidating black tool bags have become familiar. I’ve learned to unfold a tripod to just the right height. To angle a camera towards my narrator’s left cheek, framing her head from hair to collarbone and obscuring her lapel microphone. I know how to initialize an SD card; how to stop recording, then press power; and how to make the light in the room warmer or cooler based on the narrator’s proximity to a window. My technical skills are far from perfect, and it often takes me about five times longer to set up equipment than it should, but my fumbles and mistakes only reinforce my newfound appreciation for the complex science of oral history.

And yet, if oral history is a science, it is also an art.

I have learned that oral history, at its root, relies not on the positioning of the camera or the placement of the mic but on the strength of the trust carefully built by both historian and narrator during weeks of exchanges and phone calls preceding the interview itself. This trust is not quantifiable; a relationship, it turns out, is harder to assemble than a camera tripod.

I have learned how to speak my narrator’s language, repeating the terminology she’s used to reinforce her sense of ownership of her life stories. I know to follow the flow of her memories, asking open-ended questions that evoke the feelings she experienced in a time or place. I try to understand how my own biases inform my questions, and to consider how intersubjectivity influences the relationship my narrator and I can build. I have learned to listen more deeply than I ever have. Perhaps most importantly, I know to allow my narrator to guide our conversation as an equal partner in this history we’re creating together.

This summer I have become a techie and a philosopher, a stickler for spreadsheets and a careful listener, a more confident camerawoman and a historian never so acutely aware of all that she does not know. In short, I have become a scientist and an artist: an oral historian.