Tag: 9/11

Stars and Scars: A Historian’s Lessons from 9/11

by Christine Shook

Christine Shook is an independent historian with over a decade of experience in oral and public history. She earned her master’s in history from California State University, Fullerton in 2010. Her previous positions include Museum Assistant at Mission San Juan Capistrano, Exhibits and Collections Associate at the Tahoe Maritime Museum, and Historian and Assistant Vice President at Wells Fargo’s Family & Business History Center.

September 11, 2001 was an incredibly surreal day. Never a fan of mornings, I awoke late on the Pacific Coast, turned on the TV, and found some sort of devastation unfurling in the east. I didn’t know what had happened. The newscasters had temporarily moved on from the footage showing the planes hitting the World Trade Center and were instead discussing the rescue efforts and fears that the buildings surrounding the towers might collapse. Terrified and utterly confused, I turned to the Internet for answers and first saw the footage of the second plane hitting the towers, and learned about the four planes that had crashed. I spent the next hour bouncing back and forth between the computer and the tv in an attempt to discover what I missed while staying on top of the latest events. It felt like one of those days when the rest of the world should have paused while this thing worked itself out, but that wasn’t the case. I had to go to work. I tamped down the overwhelming feeling of uncertainty I was experiencing, put on my work uniform, and prepared to face the public.

As a recent high school graduate, I worked the closing shift as an attendant at a swanky hotel spa in Dana Point, California. The spa was relatively empty that day. The only exception was a couple from New York who found themselves stranded in Southern California. Unable to fly home or contact any of their friends and family, they came to the spa hoping to find a much needed distraction from the things they could not control. They didn’t stay long.

Later that night, the rest of the spa staff and I spent the hours until closing in one of those drab back rooms that only hotel staff sees, adjusting the antenna on a radio so that we could hear the latest news. As I sat listening to the radio waiting for updates about these attacks on 9/11, my mind transported me to sixty years in the past to the attack on Pearl Harbor. I began to wonder if Americans in 1941 also experienced this atmosphere of angst, remorse, anger, and uncertainty. The events of December 7, 1941 led to years of war and sacrifice. Was that where we were heading?

I was not the only one pillaging the past in search of answers about an uncertain present. Politicians, pundits, pastors — everyone seemed to be making the same comparison to Pearl Harbor, and deriving strength and certainty from the virtue with which America responded to that particular wrong. A common message seemed to be: History has taught us that America is good, so our response will follow suit. Of course, I knew from the stories of family and friends that things were more complicated than that. My grandfather earned medals for his participation in WWII but no one in my family has them today. The physical and psychological wounds with which he returned inspired him to throw those medals into the Atlantic Ocean upon receipt. As a grad student in history, I read Stud Terkel’s “The Good War” and discovered more stories like my grandfather’s that casted doubt on the flawlessness of the conflict and the glorified way in which Americans remember it. The United States’s response to 9/11, the realities of war, and the uncertainty of government actions have similarly affected people in a variety of ways over the past twenty years. While the exact failings of the response to that day vary according to political parties, few think that the United States has handled things with the storied righteousness with which it started.

My own observations and lessons about 9/11 over the past two decades have been heavily influenced by my work as a historian. For the past six-and-a-half years I helped ultra-high-net-worth families examine their historic roots in search of values and lessons that they could apply to today — using the past to guide future choices and investments. When I first began this work, the message we offered clients was always one of hope: your family not only survived X, it eventually thrived financially. There’s value to that narrative of resilience, of course, but also a danger in overconfidence. In the past few years, I’ve noticed a promising trend where family members — especially those from younger generations — want to know more and more about the hard and uncomfortable truths from their past. They appear to recognize their ancestors as flawed people with cautionary tales that accompany the celebratory.

I can only hope that this willingness to look at cherished personal histories with a critical eye will expand to include the national narrative. Perhaps the next time America faces another crisis like 9/11, the stories of people like my grandfather, who rejected a jingoistic narrative, won’t be overlooked in order to provide quick answers to the question: what now?

9/11: An Oral Historian’s Personal Recollection

by Shanna Farrell

My memories of Tuesday, September 11, 2001 are vivid. I was sitting in my second period senior English class when my teacher, who was known for his sarcasm, delivered the news.

“Hi, everyone,” he said. “I just heard that a plane hit the World Trade Center.” The class began to laugh awkwardly.

“No,” he said. “I’m serious. I don’t have any more information than that.”

A hush fell over us, but we proceeded with class as normal. I’m sure I was distracted but we were discussing books and I love discussing books. Besides, it wasn’t yet real.

When the bell rang, I walked down the hall to my current events class, where our teacher routinely had a TV playing in the back of the room so he could watch the news while he taught. That’s where I first saw the images of the plane crash. Of the burning buildings. Of people falling through the sky. Of endless smoke. Of the clear blue sky. That’s when I realized I needed to call my mother, immediately. The tragedy was now real to me.

Despite the fact that my family’s residence at the time was in upstate New York, in a small mill town built on the banks of the Hudson River that hugged the Vermont border, my mother worked in New York City. She was in educational sales and her territory covered all five boroughs. She often had appointments at Stuyvesant High School, a building that is just blocks away from the World Trade Center. I knew this because even though my birth certificate indicates something different, I was partially raised in the city. My mom would often point out Stuyvesant High School when we would drive down the West Side Highway or walk around TriBeca or buy tickets for Broadway shows in the atrium of the World Trade Center. That morning, she was on her way there.

As soon as I reached the main office of my school, I pleaded with the administrative staff to let me use the phone to call my mother.

“My mom is there. My mom is there,” I repeated. I remember the horror wash over their faces, how one of them picked up the phone and instantly dialed “9” to get me an outside line. Since my mother spent so much time in her car, she had a hard-wired cell phone, cord and all. I punched in her number, but all I got was a busy signal. I did this over and over with the same results. I called my dad and the first thing he said to me was, “I can’t reach her either.” He promised to call me as soon as he heard from my mother. I hung up the phone and turned to see a few others in line behind me waiting their turn to call family or friends who also lived in the city. I didn’t know what else to do but return to class and watch the news on loop.

I’d felt fear watching major events unfold in the past, like six years earlier when a terrorist blew up a truck bomb in front of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. That had scared me. But this fear, the type I felt while waiting to find out if my mother was alive or dead, was something entirely different. It was panicked and unrelenting. Time seemed to stand still. I could have moved from room to room or stayed in the same seat. (I do, however, remember relocating to the cafeteria at some point where TVs had been wheeled in so we could watch the media coverage.) And then I heard my name over the PA system. I had a phone call and needed to report to the office.

“She’s okay,” my dad said. “She called me from a payphone. She was in Brooklyn.”

In the days that followed I would learn that my mother was headed to Manhattan from Brooklyn that morning, but got stuck on the Brooklyn Queens Expressway while she was en route. Traffic moved slowly, if at all, and she ended up snaking her way to the part of the expressway that is just under the Brooklyn Heights Promenade, a place known for its iconic view of the lower Manhattan skyline. From there, she watched with hundreds of others as the towers burned and debris floated across the harbor as the wind blew southeast. She was eventually able to make it to Queens, where she pulled over and found a payphone. I would later watch her struggle with what she had seen that day, hear her plead with me not to get on a plane in the coming weeks for a college visit, listen to her talk to colleagues and discover she knew people on the plane that crashed into the Pentagon.

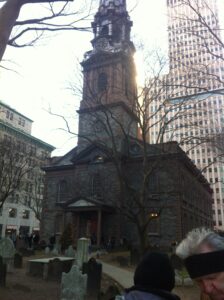

The trauma of the event was lasting for her, for me, and for us as a family. We visited Ground Zero many times and I have memories of the smoldering ashes fading into piles of debris and later becoming a gaping hole in the ground. I remember the photos of the missing people stapled to the fence surrounding the site. I remember the tone of the city and the feeling of community. I remember being so happy that my mother was alive, and so sad that others hadn’t been as lucky. I remember how filled with grief each anniversary of the attacks were each year.

In September 2011, I was starting a master’s program in oral history at Columbia University. The Columbia Center for Oral History Research had started a massive interviewing project ten years earlier, the same day the towers fell. Interviewers–staff, student, and volunteers alike– recorded hundreds of life histories with a wide range of people who were affected by the attacks. They interviewed anyone who wanted to participate and returned to many months later to interview them again. I still consider this to be an innovative model for an oral history project, especially in a field that is constantly asking itself “how soon is too soon?” (For more on this, check out Amanda Tewes’s piece on interviewing around collective trauma.)

This project served as much of the foundation of the Columbia program and the interviews became the basis for a book, After the Fall: New Yorkers Remember September 11, 2001 and the Years that Followed, which was published as I began the Master’s program. As graduate students, we read through transcripts, listened to interviews, engaged with theory related to memory and trauma-informed narratives, learned methodology for approaching sensitive interviews, and expanded our studies into other topics, like genocide and mass-incarceration. We even watched a professor interview a paramedic who had been at Ground Zero that day, live in class, offering us the opportunity to practice our question-asking skills.

It was intense. But it made me into an interviewer who isn’t afraid to shy away from difficult topics. My training also gave me space to process my own grief around the 9/11 attacks. I found myself asking my parents more about that day and how they felt in the years that followed. It gave me a concrete example around which to center my work as an oral historian and how I should approach trauma in my own interviews. How would I want to be asked about these things? How would I feel if I cried in an interview? How would my tone, pace, and velocity of speech change when a difficult subject came up? What were my boundaries and how would I express them to an interviewer? Which of my memories were solid and which were porous?

In the conversations that I had with my parents after the tenth anniversary of the tragedy, I realized that many of my memories, no matter how vividly I remember that day, were not quite accurate. My mother explained that she hasn’t actually been heading to Stuyvesant High School. Instead, she was trying to get to a school on W 33rd Street through the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, which enters Manhattan just south of the World Trade Center. This had been part of my narrative for years. My memory wasn’t perfect.

Now, twenty years later, I’m still using these experiences as the basis for how I approach trauma-centered narratives, and, for that matter, any interview where a sensitive subject comes up. It’s remarkable how much I use the same techniques that I learned in grad school, honing them over the past ten years. My pace, my tone, my body language, my ability to pause and give someone space, my interest in putting my feelings aside to privilege a narrator’s story all matters. As oral historians, we often take the life history approach, which can dredge up painful memories from the past, no matter how much we prepare in the pre-interview and planning process. I have to be ready to handle a narrator’s emotions about a troubled relationship with a parent, a divorce that proved formative to a career, a bad review in a newspaper, and yes, a terror attack.

It’s also made me mindful of people’s memories, especially around trauma. Though the historical facts of how I remember 9/11 remain static for me, the details of my mother’s experience were fuzzy. But it’s relevant to how we memorialize events, how we talk about them with our own communities, and what gets documented in the historical record. It’s also made me consider what gets left out of the left out of the story, perhaps because it happened too long ago, was repressed, or doesn’t feel as significant. For example, in talking to my mother about this very article that you’re reading, she told me that I was interviewed by the local newspaper shortly after September 11, 2001 about my experiences that day. I had my picture taken. I said that 9/11 had “changed my life.” Yet, I have no memory of being interviewed until or having my picture taken. And I have no idea why. I only vaguely remember hearing my parents talk about the article. In many of the oral history interviews that I’ve conducted over the last ten years, narrators often say to me, “I can’t remember the last time I thought about this.” That’s exactly how I felt when my mom told me about that newspaper article.

9/11 shaped me in countless ways. That cloudless Tuesday and its aftermath continue to be present in my life, following me from high school to graduate school to my work at the OHC. It’s informed the way I think about life pre-9/11 and over the past twenty years. I’m not sure my memories will ever be less vivid or more pliable, but the impact, personally and professionally, will persist.

9/11 and Interviewing around Collective Trauma

“…I very rarely ask questions about 9/11 during oral history interviews, and I’ve been trying to grapple with why that is.”

As we approach the twentieth anniversary of 9/11, I’ve been reflecting on my own memories of that fateful day in September, and its impact on how I interview others about traumatic events. Indeed, I recently realized how deeply intertwined my thoughts about 9/11 are with my oral history practice.

The first time I spoke aloud about 9/11 – aside from discussing breaking news in the days that followed – was in my introductory oral history class with Dr. Natalie Fousekis at California State University, Fullerton in August 2009. This was nearly eight years after the original events, when the terrorist group al-Qaeda coordinated the hijacking of four passenger airplanes with the intent to crash them into major US targets. This led to a tragic loss of life and shook a sense of national security for many Americans.

As an exercise about collective memory, Natalie invited the class (from youngest to oldest) to share recollections of that day. Despite the age differences (approximately early twenties to early forties), as we went around the table, it was striking that roughly twenty different stories aligned so closely, as though we were all reciting the same narrative with slightly different words. With the exception of hearing the news while getting ready for high school, my own memories were much the same. This was, of course, in part due to the media coverage Americans saw of the Twin Towers falling over and over again, which helped create a collective memory of that day. But the similarity in omissions was striking, too. I don’t remember many people discussing the plane that hit the Pentagon or Flight 93, which crashed in the fields of Pennsylvania. Later dubbed Ground Zero, even in 2009, New York City dominated our memories of 9/11.

I also remember that though the mood in the classroom was somber, none of us cried or expressed an overwhelming sense of grief. Looking back, I wonder why there wasn’t more emotion around this discussion of such a traumatic moment. The eighth anniversary of 9/11 was only weeks away, and for those who had been teenagers in 2001, that day and the ensuing War on Terror had indelibly changed our lives. In part, maybe we were already trying to analyze our own experiences as oral historians rather than vulnerable individuals, interpreting what our collective memories meant rather than sitting with their personal heaviness. Or maybe this room of California students felt more removed from the horrors of that day due to physical distance from the sites on the East Coast. But it is also possible that even eight years later, we weren’t yet ready to address these memories as collective trauma.

In the more than a decade since this classroom discussion, I have conducted hundreds of oral history interviews – many of them discussing traumatic moments for individuals and the collective. Yet, I find it strange to reflect on the centrality of 9/11 to my early oral history training, as it has been a major pitfall in my own practice as an interviewer. About three years ago, while preparing an interview outline, I suddenly realized that my narrator’s work documenting and securing collections at a major arts institution coincided with this moment in history. Luckily the narrator agreed to share her memories, and we had a fruitful discussion about the ways in which, for a time, 9/11 impacted all levels of American culture. This experience helped me register that I very rarely ask questions about 9/11 during oral history interviews, and I’ve been trying to grapple with why that is.

One possibility is that I, like many others in the field, struggle with when an event gets to become “history,” and how we choose to memorialize it. To me, 9/11 feels like yesterday, not necessarily an historical moment upon which I need to ask narrators to reflect. And I am certainly guilty of collapsing historical timelines and not concentrating on the recent past, even during long life history interviews.

But I also suspect that my omission of 9/11 in interviews has a great deal to do with the traumatic nature of that day. Like many interviewers, I’ve sometimes been reluctant to introduce topics at particular points of an oral history for fear of creating a trauma narrative where there otherwise wasn’t. And until recent training, I was not even confident in my own skills tackling trauma-informed interviews. This hurdle has a clear solution: I need to prioritize discussing potentially traumatic topics like 9/11 in pre-interviews or introducing them in the co-created interview outline.

What is less clear is how to navigate my own trauma about 9/11. How do my own memories of that day impact my willingness to ask others about it? Am I too close to the subject to be able to speak with narrators about it? Quite possibly. But one complication for all interviewers is that unlike other traumatic events with a beginning and end date, 9/11 is an ongoing reality – even twenty years later. From the recent withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan to the wide reach of the Department of Homeland Security to heightened airport screenings, we are all still living with the consequences of 9/11, and the trauma has not actually ended.

Twelve years after that classroom exercise around 9/11 and collective memory, I can appreciate Natalie’s methods all the more. I’ve learned over the course of my oral history practice that even deeply personal narratives can include elements of collective memory, and it is important to recognize such common threads in our lives as interviewers, as well.

I often preach that oral history practitioners need to acknowledge our biases so that we can better overcome them or even use them to our advantage. For me, examining my blind spot around 9/11 has also encouraged me to think about incorporating more recent and ongoing historical events into interviews. Not only is this reflection an important addition to the historical record, it is part of our essential work to help narrators make meaning of their lives through oral history. Similarly, evaluating my own blind spot around 9/11 has helped me recognize the blind spots in the collective memory of that day – such as narratives that leave out Flight 93 or the attack at the Pentagon – and encouraged me to think about how oral history can help fill these gaps. As we recognize the twentieth anniversary of 9/11, this work feels more necessary than ever.