Tag: interviews

The Value of Open Space

The Bay Area is beautiful. Its myriad of picturesque beaches, mountains, woods, and lakes is a big part of why it’s such a desirable place to live. And since March, when the California shelter-in-place order was issued to slow the spread of the coronavirus pandemic, the value of these outdoor spaces has never been more clear.

The East Bay Regional Park District has worked to preserve open space since its founding in 1934. Over the years, it has acquired 125,000 acres of land, which spans 73 parks. The public access to nature that the concert of parks provide adds to quality of life here, especially with the parks’ proximity to urban areas (which is detailed in Season 5 of The Berkeley Remix podcast, Hidden Heroes).

There are many people in the district’s network, both those who make up the workforce and those who help it thrive in other ways, like documenting its history, selling their land to them, and advocating for its mission. Since 2017, I’ve had the pleasure of leading the East Bay Regional Park District Parkland Oral History Project, for which I have the opportunity to record the stories of the people who make the district special.

This past year, I interviewed ranchers, activists, a maintenance worker, an artist, the daughter of a historian, and a park planner, all of whom had unique perspectives to share about the legacy of the district. Here are the ways in which each of their stories speak to the value of preserving open space:

Diane Lando grew up in the East Bay on a ranch. She became a writer, drawing inspiration from her childhood. As the Brentwood Poet Laureate, she published The Brentwood Chronicles, which consists of two books. These books express just how important growing up on the ranch had been for her, giving her a sense of independence and self.

Raili Glenn immigrated to the United States from Finland and settled in California as a newly married woman. She had a successful career in real estate and she and her late husband bought a house in Las Trampas, which is now owned by the EBRPD. This house meant a great deal to her —it’s beauty, quiet, and charm helped her find home in the parks.

Roy Peach grew up in the East Bay, spending much of his childhood in Sibley Quarry, which is now owned by the park. Growing up here, he learned about the environment, geology, and himself as he spent as much time as he could outdoors. His love of nature has followed him into adulthood, and camping has continued to be an important pastime.

Ron Batteate is a fourth generation rancher. He grew up in the East Bay, following in the footsteps of the men who came before him. He leases land from the district where he grazes his cattle. His love for open space and his livestock runs deep, evident in the way he talks about the importance of understanding nature with commitment and passion. If I were a cow, I’d want to be in Ron’s herd.

Janet Wright grew up in Kensington with parents who were very involved with their community. Her father, Louis Stein, was a pharmacist by day and a local historian by night. He collected artifacts from around town, which proved to be important in the documentation of local history. The maps, photos, letters, newspapers, ephemera — and horse carriage — that he collected are now archived at both the History Center in Pleasant Hill and with the Contra Costa Historical Society. These materials help tell the story of the importance of the district in many people’s lives.

Glenn Adams is the nephew of Wesley Adams, the district’s first field employee. Wesley was hired in 1937 and had a long career with the district, retiring after decades of service. Glenn fondly remembers his uncle Wes, who he says shaped his life greatly, including passing along his passion for the parks. Glenn has in turn shared his love of the outdoors with his family, who continue to use the parks today.

Mary Lenztner grew up on a ranch in Deer Valley that her parents, who both immigrated from the Azores, bought in 1935. She moved to San Jose with her mother after her father’s death, but returned to the area later as an adult. As her children got older, she became curious about her family’s ranching legacy. She learned about raising cattle, and went on to take over her family’s ranch. She lived there, raising cattle and other livestock, for 25 years before selling it to the district. Her relationship with this land helped her connect with her family and their past, and her interview drives home the importance of place in our lives.

Bev Marshall and Kathy Gleason live in Concord near the Naval Weapon Stations, part of which is now owned by the district . When they were deactivating the base, they both fought to keep it open space. Their work helped them form a lifelong friendship, find community, and a voice in local politics, while successfully limiting development in the area.

Rev. Diana McDaniel is a reverend in Oakland and is the President of Board for the Friends of Port Chicago. She has long been active in educating the public about the Port Chicago tragedy, which her uncle was involved in. She works with the district (and National Park Service) to make sure the story of what happened at Port Chicago isn’t forgotten. Her story illustrates how important parks are not just for open space, but for public history, too.

John Lytle was a maintenance worker at the Concord Naval Weapons Station where he specialized in technology. He found fulfillment in his work there over the years, and his interview demonstrates the careful planning that goes into transitioning a naval base into a public park.

Brian Holt is a longtime EBPRD employee who currently serves as a Chief Planner. He has been involved in many of the district’s initiatives, including acquiring much of its land. He works with community members, trying to understand issues from different perspectives. He cultivates understanding of the nuances of each issue, ultimately informing the district’s involvement in preserving open space.

All of these narrators demonstrate just how important the district is to preserving public space, especially space that is accessible to everyone. Each person illustrates the power the parks and the communities that spring up within them, which is more important than ever during these tumultuous times.

This year, I interviewed:

Diane Lando

Raili Glenn

Glenn Adams

Roy Peach

Mary Lentzner

Beverly Marshall

Kathy Gleason

Janet Wright

Ron Batteate

John Lytle

Brian Holt

Reverend Diana McDaniel

And

Melvin Edwards

Peter Bradley

Both for the GRI African American Artist Initiative, outlined in Amanda Tewes’ blog post

#notoralhistory

by Shanna Farrell

@shanna_farrell

During the first few months that I was settling into life in the Bay Area after moving across the country, I often listened to WNYC, a New York City-based radio station. One morning, as I was riding my bike to work, the host of their call-in show, akin to KQED’s Forum, announced the upcoming segment.

“What was better back in the day?” the host asked. “It’s an oral history of nostalgia, starring you. Tell us about what you think was better from a previous era, why you miss it, and whether you think it’s better because of nostalgia, or because things were, empirically, better back in the day. Call us or post below.”

My heart started to race. This call out felt so personal. They had gotten it so wrong. I pulled over and dialed their number. A producer answered, unaware of their error.

“I just heard your next segment is on the oral history of nostalgia,” I said. “But that’s not oral history.”

Confused, she asked me to explain what I meant. It was October of 2013, and I was fresh off earning a Master’s Degree in Oral History. I had spent a year taking method and theory classes, learning about what defines the discipline, exploring its boundaries. I had my interviews critiqued, my questions workshopped, and had been pushed to dig deeper into my research, all in the name of preparation. This felt dismissive of the work that we oral historians put into our interviews. It devalued the time (and money) that I’d put into my degree, and the job that I had just landed at UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center.

As I tried to explain what oral history is and how what they were doing in this segment wasn’t it, I realized it would be impossible to fit into a two sentence elevator pitch. There’s so much that defines oral history, that makes it unique, distinct from other methods, that I could feel myself having trouble reducing it to something easy to pitch, just as they had to listeners.

Looking back on that moment, I wish I would have said that oral history is defined by the planning, the transparency, the collaboration, the recording, intersubjectivity, the preservation, the legacy. I wish I would have said that it could take weeks to carefully research and write an interview outline, hours to build rapport, and months to complete an interview series. I wish I would have said that it takes practice to craft questions and to listen in stereo, picking up on the things that aren’t said, and to be comfortable sitting in silence.

After I hung up the phone, I thought about why they called this segment “oral history.” I’m still thinking about it. The term became popular when magazines started running vox populi style interviews weaving together soundbites from different people to create a narrative. They ran pieces about the about the making of a movie, like Jurassic Park, or a TV show, like The Simpsons. Later, it became a household term when StoryCorps partnered with NPR to bring us our Friday driveway moments, produced from a carefully edited interview excerpt. Lately, it has seeped into literature. More and more, I see “oral history” to describe a work of memoir, creative nonfiction, and even fiction. Recently, I was reading the Sunday New York Times book review section and they positioned a new memoir as “part oral history, part urban history.” I couldn’t wrap my head around what this meant. How was it oral history? Had the author done interviews? How was this different from a regular memoir? And lately, I’ve seen a few journalists refer to themselves as oral historians without seeming like they have a solid understanding of what the term means, aside from it involving interviews.

Where does this lack of understanding stem from? Why is the term “oral history” battered around so easily? When did it first get misappropriated? The origin of the Entertainment Weekly and Vanity Fair versions are relatively straightforward, descending from the Jean Stein-style books like Edie: American Biography, which is constructed from interviews with people who knew Edie Sedgwick after her death in 1971, or books that recounted musical eras, like We Got the Neutron Bomb by Mark Spitz and Brendan Mullen (which also served as my first introduction to oral history when I was in high school) or Please Kill Me by Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain. As for where the rest of it came from – like the recent trend in literature – it’s anyone’s guess.

I’m not the only one who has been noticing this trend. In 2014, the anonymous user @notoralhistory joined Twitter. For a while, they tweeted examples of people labeling articles or projects as oral history that were, indeed, not actually oral history. They now promote examples of oral history and engage in conversations around best practices. There are practitioners who also tweet bad examples of oral history, using #notoralhistory, which are often amusing, and then maddening, and then amusing again.

The problem with these mediums is that they can’t accomplish the same things that actual oral history does. These narratives just provide soundbites, while oral history gives us much more context. They don’t include any audio (or video), so we lose the ability to connect with a human voice. They are highly edited, whereas oral history allows people to speak in their own style. They are usually layered with other voices, instead of giving someone individual space to fully narrate their own story.

The link in @notoralhistory’s bio takes you to the Oral History Association’s website, to the page where they define oral history. Here, they share a quote from Donald Ritchie’s book, Doing Oral History. He writes:

“Oral History collects memories and personal commentaries of historical significance through recorded interviews. An oral history interview generally consists of a well-prepared interviewer questioning an interviewee and recording their exchange in audio or video format. Recordings of the interviews are transcribed, summarized, or indexed and then placed in a library or archives. These interviews may be used for research or excerpted in a publication, radio or video documentary, museum exhibition, dramatization or other form of public presentation. Recordings, transcripts, catalogs, photographs and related documentary materials can also be posted on the Internet. Oral history does not include random taping, such as President Richard Nixon’s surreptitious recording of his White House conversations, nor does it refer to recorded speeches, wiretapping, personal diaries on tape, or other sound recordings that lack the dialogue between interviewer and interviewee.”

Oral history can accomplish so much. It gives us insight into the past, hearing directly from the people who lived through various moments in history. By archiving the recordings, we can listen to how narrators tell their stories, and gain insight into why they told it this way. We can put a human face on history and learn from those who came before us. And, when oral history is done right, through careful preparation, research, and recording, we can ensure that these people are not forgotten, their stories not reduced to a soundbite.

It is with similar intention that we are devoting many of our articles this month that revolve around the boundaries of oral history. You’ll hear from us about our experience doing oral history and what makes it different from other disciplines and methods. We hope you follow along.

Primary Sources: USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive

The Library recently acquired the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive, a collection of unedited, primary source interviews with survivors and witnesses of genocide and mass violence. The bulk of the testimonies included relate to the Holocaust, as collecting these was the original purpose of the project. Now the archive has expanded to include testimonies from the 1994 Rwandan Tutsi Genocide, the 1937 Nanjing Massacre, the Armenian Genocide, the Cambodian Genocide, the Guatemalan Genocides, the ongoing South Sudan Civil war, the Central African Republic conflict and anti-Rohingya mass violence in Myamar.

OHC Director’s Column, March 2019

by Martin Meeker; @MartinDMeeker

How do thoughtful, articulate, quiet people who have something to say get heard? In this day and age in which the loudest voices, the most outlandish ideas, and the most shocking stories get the greatest attention, is there even room for the longform, deep-dive oral histories that the Oral History Center produces? We certainly think that there is — actually, we’re pretty sure that not only is there a place for these interviews, but there is a real need for them. This leaves us with the question: how do we spread word of the remarkable interviews that we conduct? What’s the best way for people who could benefit from our work to learn about it and thus use it?

Since you’re reading this newsletter, you’re already in the loop and engaged with what we do (and we thank you for paying attention!). But we are also constantly examining the ways in which we attempt to connect and considering potential new avenues for outreach. Like most every organization today, we have a pretty robust social media presence. We use our feeds (twitter, facebook, instagram, youtube, and soundcloud) to announce the completion of new oral histories, to pay tribute to narrators who’ve achieved something or sadly passed away, or just to share things reasonably related to oral history which might interest our community. Have you engaged with us on social media? Are you interested in what we have to say? Do you think we might use it better? We want to know.

We try to extend our reach by hosting educational seminars and institutes, by speaking to classes and community groups, and by simply answering our emails (but we get a lot, so apologies in advance if I take a few days to get back to you!). We recognize that a 300-page oral history transcript is sometimes a difficult nut to crack, so we produce brief clips introducing folks to some main themes or interesting moments drawn from the interviews, and share these as widely as possible. We have begun producing podcasts and, soon, longer format videos to show ways in which the original recordings of our interviews can be used to create engaging and informative analytic pieces — and thus encouraging others to use our oral histories in similar ways. And, of course our transcripts continue to provide extraordinarily valuable, irreplaceable evidentiary bases to mountains of books, articles, and theses. What are other options that we might use to spread word of the remarkable interviews? How might the transcripts and recordings be used in novel and enlightening ways?

The big questions posed above are now being addressed head-on by our newly refurbished and expanded production/operations/communications team at the Oral History Center. As a result of a recent search to fulfill our “Communications Specialist III” vacancy, we hired two immensely qualified individuals. David Dunham, who has been on our staff for many years in other capacities, has assumed the new role of Operations Manager; Jill Schlessinger, who came to us from UCB Student Affairs, has joined us as Communications Manager. In addition to working as a team to make sure we continue our successful production of dozens of oral histories every year, Jill and David are tackling these very thorny questions focused on how to raise our collective voice so that the voices of narrators are heard and the content of their oral histories is widely known. Expect to hear more from us in the coming months as all of this comes to fruition. As always, we welcome your input and we’re happy to listen — you might say that’s something we do rather well!

Martin Meeker

Charles B. Faulhaber Director

Oral History Center Leads Introductory Workshop

by Shanna Farrell; @shanna_farrell

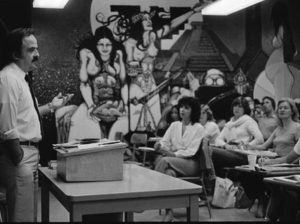

When Spring rains shower the Bay Area, saturating the ground and greying the skies, we know it’s time for our annual Introductory Oral History Workshop. On Saturday, March 2nd, as raindrops beat against our stained-glass windows, we welcomed a group of forty to campus, where they they learned the nuts and bolts of doing oral history . They braved the wet weather to join us from all over Northern California , and even as far as North Carolina.

The oral history project topics of attendees varied from burlesque to the Third World Liberation Front, and from the mining industry to environmental conservation. However, we design our introductory seminars to be applicable for everyone. OHC Director Martin Meeker gave an overview of what makes oral history oral history. Paul Burnett and Roger Eardley-Pryor discussed the intricacies of project planning. Amanda Tewes and Shanna Farrell led a discussion on interviewing techniques. Burnett and Meeker shared recording tips and tricks, and Tewes and Todd Holmes shared potential uses of oral history drawing from a cadre of past projects.

The workshop also featured a live interview exercise led by Farrell. One of the workshop participants, Trisha Pritikin, volunteered to be interviewed by Farrell so other attendees could see an oral history unfold in real time. Eardley-Pryor then engaged Farrell, Pritikin, and workshop participants in a group discussion. Attendees shared their observations, asked Farrell about certain lines of questioning , and inquired how Pritikin felt sitting in the “hotseat.”

These workshops always prove inspiring for OHC interviewers, staff, and student supporters because we interact with attendees who share our passion for oral history.

Thanks to all of you who made the workshop so great! And if you missed it this year, we’ll see you next Spring in 2020!

Want more oral history training? Check out our Advanced Oral History Summer Institute. Email Shanna Farrell (sfarrell@library.berkeley.edu) with questions.

The Oral History Center Year in Review: Our Favorite Interview Moments

The Oral History Center has had a productive year, and interviewed many people. Here’s some of our favorite moments from our 2018 interviews. We hope you enjoy them as much as we did!

Martin Meeker:

Of the dozens of revelatory, challenging, or even hilarious moments in my interviews this year, I find it difficult to highlight just one. But I keep coming back to this moment in my interview with famed ACLU attorney Marshall Krause. Krause defended a number of individuals charged with obscenity in San Francisco in the 1960s, including Vorpal Gallery owner Muldoon Elder for putting Ron Boise’s erotic Kama Sutra sculptures on display. While recounting the story, Krause mentioned that he had one of the artworks in question, so I asked him to bring it out to show on camera. I then asked him to provide the kind of defense he did in the courtroom in 1964. Krause’s sensitive, insightful, convincing words made it obvious why the jury acquitted Elder of the charges, thus giving Krause and the cause of the freedom of expression a victory.

Amanda Tewes:

My favorite interview moment of 2018 occurred when I interviewed Bay Area herbalist and aromatherapist Jeanne Rose. In the 1960s, Rose was the couturier for bands like Jefferson Airplane and was very plugged into the local rock and roll scene. During one of our sessions together, Rose recounted her experience at the Altamont Speedway Free Festival on December 6, 1969, when an agitated audience of about 300,000 erupted into violence. Rose watched the chaos from above the crowd, but still recalls the strong emotions from that day. Hearing about the event firsthand reinforced how scary and chaotic the events must have been for concert goers. Interestingly, Rose marked this concert as “the end” of rock and roll.

Paul Burnett:

had started an underground called the Werewolves. We spent quite a bit of

time on that for the first few months. I don’t think we ever found any. We

once raided an outfit that were presumably Werewolves. I don’t remember

what happened to them, except that we sort of used movie techniques to make

the raid, coming through the skylights.

Todd Holmes:

My favorite moment this year was interviewing Professor James C. Scott at his farm in Durham, Connecticut. The Sterling Professor of Political Science and Anthropology at Yale University, Scott is widely regarded as one of the most influential thinkers of our time, producing an unparalleled corpus of books over the last 50 years on peasant politics, resistance, and state governance, which today are standard reading across a host of disciplines worldwide. Yet in the interviews, we get a glimpse of the unassuming human being behind the books as Scott discusses the two principles that have always underpinned his approach to academic work – principles he stresses . The first: “Don’t ever be afraid to be an army of one in a crowd of a hundred,” a philosophy of independence he came to embrace during his Quaker education as a young man. The second: “If you’re not having fun, what the hell are you doing?” For those who know Jim Scott, the latter is certainly an oft-quoted remark he has extolled to colleagues and graduate students for decades. Spending the weekend at his farm, I quickly realized that those principles were not just lofty ideals, but words he lived by, and I would be wise to do the same.

Shanna Farrell:

My favorite moment this year was during an interview with WWII Veteran Lawson Sakai, who is in his nineties, for the East Bay Regional Park Parkland Oral History Project. Sakai’s parent immigrated from Japan, making him Nisei, or second generation. He spoke about needing to flee California to avoid internment, and the role that farming in the Central Valley played to rebuild the Japanese community in the aftermath. Driscoll Farms was just getting started and needed help growing strawberries. They recruited Japanese farmers, asked them to farm the land, and split profits with them 50/50. After hearing how Driscoll helped many people get back on their feet after losing everything in the wake of Executive Order 9066, I scoured my food history books and didn’t find any information about this. I felt like I had stumbled upon a hidden historical gem.

Roger Eardley-Pryor:

Interviewing Aaron Mair—the 57th president of the Sierra Club and the Club’s first African-American president—provided my favorite interview moments this year. We conducted Aaron’s initial interview session at the Hagood Mill Historic Site in the upcountry of South Carolina. As his family’s genealogist, Aaron has the 1865 records of his enslaved great, great grandfather Zion McKenzie’s emancipation from the Hagood family. Before interviewing at the Hagood Mill site, Aaron and I visited the humble, un-fenced cemetery of his enslaved ancestors, whose rough, uncut gravestones lay just outside the Hagood family’s iron-fenced grave site with grandiose tombs and Confederate soldier crosses. Later, during his interview, Aaron recounted his ancestors’ remarkable stories from slavery to freedom and their purchase of farm land that remains in Aaron’s family today. His family’s narrative, from human dominion to sustainable stewardship of land, informs Aaron’s ideas on environmental responsibility. And it helped inspire Aaron’s initiatives as Sierra Club president to unify activism for environmental rights with civil rights and labor rights. Aaron takes seriously Sierra Club founder John Muir’s admonition that “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.”

Mair and Eardley-Pryor

OHC Commences Project to Commemorate 50th Anniversary of Chicana/o Studies

by Todd Holmes

Today, courses on the Mexican American experience can be found at nearly every college campus across the nation. In an academic environment long entrenched within the mold of Western Europe, such curriculum is nothing short of a miraculous testament to the diversification of American education. Indeed, the subject has its own journals, national organizations, student groups, academic departments, and specialized degrees. Yet fifty years ago, the discipline of Chicana/o Studies—as the field of study became known—was just taking shape and, above all, struggling for legitimacy.

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the discipline, the OHC initiated the Chicana/o Studies Oral History Project. Led by Todd Holmes, the project documents the historical development of the field through in-depth interviews with the first generation of scholars who shaped it. Holmes began working on the project in the fall of 2016 with the initial step of putting together an advisory council composed of Chicana/o scholars from around the country. Based on the council’s recommendations, over 25 prominent scholars were selected to be interviewed—scholars whose pioneering research and innovative work played a significant role in building the discipline over the last five decades. Holmes then commenced an ambitious fundraising campaign, going directly to the home universities of the featured scholars. To date, the project has received generous support from a host of academic institutions, including the University of California Office of the President, California State University Office of the Chancellor, Stanford University, Arizona State University, and the University of Texas at Austin.

The interviews will offer an important look at the formation of Chicana/o Studies, as well as the experiences of those who built it. Such areas of discussion include their family background, undergraduate and graduate experiences, and academic career as faculty members. With most—if not all—of these scholars standing as the first in the families to attend college, and certainly among the first cohort of Mexican American graduate students and faculty, their experiences highlight the evolution of the field, the diversification of higher education, and the long struggle that underpinned both. Moreover, the interviews trace significant shifts within the field of Chicana/o Studies over the decades, and how the field expanded from college campuses in California and Texas to a nationally recognized discipline of study.

All interviews are slated to be completed by the summer of 2019. When done, they will be featured on a dedicated page of the Center’s website. Moreover, the oral histories will form the heart of a documentary film, tentatively titled, Chicana/o Studies: The Legacy of A Movement and the Forging of A Discipline. The OHC is thrilled to make this foray into film and collaborate with veteran producer Ray Telles and others in this exciting effort. Stay tuned for further updates in 2019!

First Generation Scholars

Norma Alarcón (UC Berkeley)

Tomás Almaguer (San Francisco State)

Rudy Acuňa (CSU Northridge)

Mario Barrera (UC Berkeley)

Albert Camarillo (Stanford)

Martha Cotera (UT Austin)

Antonia Castaňeda (St. Mary’s College)

Edward Escobar (Arizona State)

Juan Gómez-Quiňones (UCLA)

Mario T. García (UC Santa Barbara)

Deena González (Loyola Marymount)

Richard Griswold Castillo (San Diego State)

Ramón Guitierrez (University of Chicago)

José E. Limón (UT Austin)

David Montejano (UC Berkeley)

Emma Pérez (University of Arizona)

Ricardo Romo (UT San Antonio)

Raquel Rubio-Goldsmith (University of Arizona)

Vicki Ruiz (UC Irvine)

Ramón Saldivar (Stanford)

Rita Sanchez (San Diego State)

Rosaura Sánchez (UC San Diego)

Carlos Vélez-Ibáňez (Arizona State)

Emilio Zamora (UT Austin)

Patricia Zavella (UC Santa Cruz)

For more information on the project, its participants, and to view the film’s trailer, visit the project page..

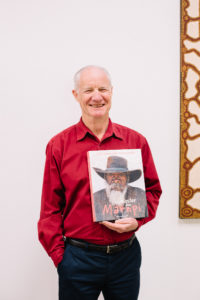

OHC Advanced Oral History Summer Institute Alumni Spotlight: Alec O’Halloran

We recently caught up with one of our Advanced Oral History Summer Institute alums, Alec O’Halloran, who recently published a book that was influenced by his work with us. His book, The Master from Marnpi, is based on oral history interviews. O’Halloran reflects on his work, his time with us, and the release on his book.

(Applications are open now for the 2019 Summer Institute from August 5-9. Apply now!)

Q: How did you first come to oral history?

I don’t have a ‘first’ recollection. I’ve always been interested in stories and in the 1990s (in my forties) I was drawn to the larger story of Aboriginal art and history in Australia, which I knew very little about. This led to reading autobiographies and biographies of Indigenous people, as well as attending art exhibitions etc. Oral history interviews were often quoted in stories about Aboriginal artists, particularly older people from remote parts of Australia that most of our population knew very little about.

When I began researching the life of an artist whose work I admired, Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri, I found out he had done two recorded interviews in his language, Pintupi, a decade before he passed away (1998). I found those interviews – or their translated transcriptions – fascinating! What a life he had led… so different to mine. Those interviews motivated me to look around for more oral history work that engaged with Aboriginal artists in particular.

Q: Tell us a little bit about the project you were working on when you attended the Advanced Oral History Summer Institute.

I attended the Institute in 2010, in part with support of a travel grant from my institution, The Australian National University in Canberra, where I was undertaking a doctoral program in Interdisciplinary Studies. My thesis project was the life and art of Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri. I had a rough draft of his life story by that stage, and I was mostly preoccupied with assembling the chronology of events, rather than comprehending his character.

Q: How did your work benefit from the Summer Institute?

One thing I still remember from one of the guest lecturers was about ‘listening and hearing’ when working with recorded interviews. And with so many conversations with fellow participants about each other’s projects, I realised I was not fully engaging with the materials I had at hand. So, I when I returned home to Sydney I took a more rigorous approach.

I went back to the original recordings of Namarari (one audio, one video), and the transcripts, and tasked myself to see and hear more than I had before. To not only track events and incidents and the chronology of his life story, but to look beneath and between the lines and sounds for character and personality traits, for nuanced references to culture, to allusions to relationships with other people. I said to myself, ‘These two interviews are like gold, I need to use them to the fullest’. So the Institute motivated me to be much more dedicated to the oral history component of the biographical research about Namarari’s life and art. This certainly improved the quality of my writing when I was integrating Namarari’s voice into a wider story that involved multiple voices and archival sources.

Another outcome too. Oral history as a data-making history-creating method became more important to me. I don’t think I was an expert practitioner, so I tried to improve the quality of my interviewing work. This involved better planning of interviews and better conduct as the interviewer. Also, I saw that I had an opportunity to contribute to the field in a meaningful way.

The region where Namarari lived is called the Western Desert. It occupies a vast swathe of Central Australia. (Bigger than Texas!) My field work took me to that region, first by air to Alice Springs, and then by four-wheel drive (essential for the outback gravel roads). I realised I could do additional oral history work outside my specific research project as part of my travels. During 2011-13 I was awarded two oral history grants by the Northern Territory Government, which I applied to producing two community oral history reports: for the desert communities of Mount Liebig and Kintore. I interviewed some twenty Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people and submitted a report, and deposited the interviews with the Northern Territory Archives Service in Darwin. I hope that one day a community member or researcher will come along who wants to write a local history of those places and find those interviews… they can then serve a good purpose. Importantly, but sadly, some of the people I interviewed have passed away.

Q: What’s the status of your project now?

My project, to produce an authorised biography on the life and art career of Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri, is complete! The master from Marnpi was released on 7 September 2018.

See my website for more information www.alecohalloran.com

Q: How did your biography, The Master from Marnpi, benefit from the use of oral history?

Namarari passed away in 1998, before I started my research, so I never met him and I could not interview him. This contrasts sharply with the majority of Aboriginal artist’s biographies in recent decades in Australia – they are invariably deep collaborations between the author and subject.

My narration of Namarari’s life story is based on his testimony: two interviews recorded in Pintupi, in 1989 and 1992, each conducted in the Western Desert by non-Aboriginal researchers who had travelled there for that purpose (and to interview other Aboriginal people of the area).

Thus it is his (translated and transcribed) voice that runs through the chapters. The many gaps are filled, where possible, with other oral history interviews I did with his relatives, and with art advisers who worked with him across his art career (1971-1998). I also drew on other oral histories, both my original interviews and from the archives, to enrich the narrative, applying more details to local histories of place, and shining a light on prevailing attitudes and circumstances that Namarari and his Aboriginal countrymen found themselves in. Where possible, I added salient photographs from a wide range of archives to illustrate what was referred to in the text by people who were ‘there at the time’.

Q: You have some visual components in the book, like maps. How did you weave visual elements with oral history?

The non-text items are: maps (of Australia, and the Western Desert region where Namarari lived), diagrams (eg, the Aboriginal kinship system), tables (eg, Namarari’s annual art output from 1971 to 1998), photographs of people, places (eg, desert scenes, Namarari’s house), and art (primarily his paintings).

The visual components serve to show the reader something of what the story-teller (eg, Namarari or his relatives) was talking about. If it was an important water-source location from his childhood in the 1930s, I would include a photograph. If it was a settlement where he lived in the 1950s, I would look for appropriate pictures from that era. Unsurprisingly there are many more useful photographs from the 1990s than the 1950s.

I applied a policy of sorts to the inclusion of images: it had to illuminate something in the text, rather than being a decorative piece to fill a space. I sometimes juxtaposed images to make a point, such as two artworks that had a subtle feature in common.

Q: What kind of projects do you draw inspiration from?

I have really been preoccupied with my book for several years, so I haven’t been looking for extra inspiration. When I was doing the biographical research I drew inspiration (and understanding) from reading Indigenous autobiographies… they often had the raw truth of historical circumstance from the mouths of those who experienced events and situations and policies.

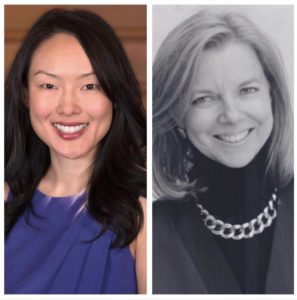

11/13 Event: Women in Bay Area Politics Panel and Discussion

By Amanda Tewes, OHC interviewer

Join us on November 13, 2018, 6-8 PM at The Ruby, a women’s creative working space in San Francisco! The festivities feature a panel discussion with Supervisor Jane Kim and Close the Gap California founder Mary Hughes.

1992 has been dubbed “The Year of the Woman,” a phenomenon in which a wave of women candidates swept local and national races for public office. California led this charge by becoming the first state in American history to be represented by two women senators—Barbara Boxer and Dianne Feinstein.

And yet, 1992 was not the beginning of women’s political activism, but rather the culmination of decades of organization encouraging women to get involved and run for office. For generations, Bay Area women have built the foundations of political activism that span neighborhood organizations to support networks. And their stories inform our present.

As engaged citizens, we need to know more about these women who helped create a space for themselves in Bay Area political life. What drives women to run for elected office, to fight for affordable housing and environmental regulations, to fundraise for women candidates? What challenges and successes have women encountered in politics?

In order to document these stories, I am developing the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project to record the history of these local women and their impact on and journeys through politics. The Oral History Center continues to preserve stories about California politicians, but this project is unique in that it focuses on women in one geographic region in order to get a clearer picture of the breadth of political work women have been doing on the ground and behind the scenes.

This topic is both historical and part of a contemporary conversation about the role of women in American politics. Given this surge of women in politics and the upcoming hundredth anniversary of women’s suffrage, now is the time to undertake this endeavor to celebrate and learn from Bay Area women who have shaped local and national politics.

Join us to kickoff this the Bay Area Women in Politics Oral History Project with an event on November 13, 2018, 6-8 PM at The Ruby, a women’s creative working space in San Francisco! The festivities feature a panel discussion with Supervisor Jane Kim and Close the Gap California founder Mary Hughes.

Advanced Oral History Summer Institute Alum Spotlight: Kelly Navies

We recently caught up with Kelly Navies, who joined us in 2013 for our Summer Institute. She is now the Museum Specialist in Oral History at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, where she coordinates their Oral History program. We talked to her about how she came to oral history, what she learned at the Institute, and her current work with the Smithsonian.

Q: How did you first come to oral history?

A: I first came to oral history, while I was an undergraduate at UC Berkeley in the African American Studies Department back in the early 1990s. In the Fall semester of my senior year, I took two courses which had a profound impact on my life; African American Poetry with the late June Jordan, and Images of Black Women in Literature with the late Barbara Christian. Prof. Christian assigned an optional paper to write about a maternal ancestor who’d lived during the 19th century. At the same time, June ( she preferred to be called, June), assigned a poem about mothers. Receiving these two assignments at the same time, inspired me to decide to pursue a research project on a maternal ancestor my mother had been telling me about all my life, but whom she actually knew very little about. All she knew was that she had been enslaved in Asheville, NC and had lived over 100 years into the 1950s, when my youthful mother had actually met her. At the time, all 6 of my grandmother’s siblings were still living ( she was deceased), so I embarked upon an oral history project to interview them all about their grandmother. Through a combination of genealogical research and oral history interviews, I eventually learned that she was named, Elizabeth Gudger Stevens, had indeed been born into slavery in Asheville, NC and had lived until 1956, when she was either 102 or 106, depending on who you believe ( no birth records, of course). It must be added that the only reason I knew “oral history” was a thing at all was because of a 7th grade English assignment and being introduced to Zora Neale Hurston at an early age.

Q: You attended the Advanced Oral History Summer Institute in 2013. What project were working on?

A: When I came to the Advanced Oral History Summer Institute in 2013, I was working as a Special Collections Librarian and Oral Historian for the Washington DC Public Library System. I had received an MLIS grant to pursue the “U Street Oral History Project.” The U Street corridor was the thriving heart of the African American business and cultural community in Washington, DC up until 1968, when many of the businesses were destroyed during the urban upheaval that followed the assassination of Dr. King. In fact, it remained a central location for Black life in Washington, DC up until the recent demographic transformation that has marked the city. For this project, I conducted over a dozen audio interviews that are now available from the DC Public library website: (dclibrary.org) Three audio clips from this project have been made into podcasts that are also available from the DC Public Library website. I also held a public program at the Busboys and Poets restaurant on 14th St., right off of the historic U Street corridor, where I invited interviewees to participate. Finally, I shared the research project on a radio program at WPFW.

Q: How did your work benefit from the Summer Institute?

A: The Summer Institute introduced me to the work of other oral historians from around the world working in a variety of disciplines from academia to independent scholars and artists. I have kept in touch with several, in fact. It also brought me up to speed on the technological and theoretical state of the field. Finally, I really enjoyed learning about Robin Nagle’s oral history work with sanitation workers.

Q: You now work with the Smithsonian. What’s the role of oral history at the museum?

A: As Museum Specialist in Oral History here at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), I coordinate the oral history program, which involves planning, budgeting, developing projects in collaboration with curators, and yes, interviewing. All of our interviews are filmed. However, I don’t conduct all of the interviews- in some cases, I conduct the research, help develop the questions, and handle the logistics. I also do trainings for classes and community groups.

Q: How do you get the public to engage with oral history?

A: Our oral history collection is cataloged along with other artifacts and are available for use in exhibitions for as long as we preserve them. Most recently, we conducted interviews for the Poor People’s Campaign Exhibition, City of Hope, and clips from those interviews were included in the exhibition. Visitors to the museum will also find oral history interviews located throughout the museum. For example, in our community galleries on the third floor, there is a clip of an interview I conducted with Mr. Frank Wright about his family’s generational involvement in oyster fishing on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. The oral history program also includes thousands of recordings captured in our Reflections Booths which are located in the history galleries. Here, visitors choose a question and record their answers in two minutes or less on a built-in camera. They then can choose to email it to themselves and/or share it with us.

The Community Curation Project is sponsored by the Smith Fund. Also, the full name of the Poor People’s Campaign exhibition is: City of Hope: Resurrection City & the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign. It is curated by Aaron Bryant and is on view at the National Museum of American History.

Q: What do you hope the public takes away from the oral histories in the Smithsonian’s collection?

A: When visitors encounter oral history in the museum, I hope they understand that history is a living breathing thing and not just something you read about in books. I hope it increases their awareness and interest in the stories of their elders and others around them.

Q: What kind of projects do you draw inspiration from?

A: I find all of my projects/interviews inspirational. The oral histories of African Americans reveal deep truths about America and about the human condition, overall. Each story I capture reminds me that there are so many other stories. oral history is a passion that is endlessly gratifying. Most recently, I had an experience that speaks to the significance of recording these stories. I interviewed a woman who knew that she wouldn’t be with us much longer-a black woman who had accomplished much in her life, and yet was still worried that her work might be forgotten-her narrative was profound and reflective. She passed away not long after and her family asked me to share some of what I had learned about her life at the memorial service. I truly consider the work we do, as oral historians, to be a sacred honor. We facilitate and capture heroic stories of ordinary individuals that are often relegated to the margins.