The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Hindi

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

The two great Indian epics, the Mahābhārata and the Ramayana, dominate South Asian cultures in ways that few other literary productions do. Both epics have to do with the heroic exploits of the human incarnation of the Hindu deity Vishnu, one of the most widely worshipped gods of the Hindu pantheon. The Ramayana deals with the story of King Ramachandra, the seventh incarnation of Vishnu, who came down to Earth to establish just rule and a harmonious society.

King Rama is not only the ideal monarch and warrior but also embodies the virtues of justice, wisdom, patience, and perseverance. He is an obedient son, a generous brother, and a caring husband. His rule became synonymous with justice and good governance so that throughout the centuries the expression rama rajya (Rama’s rule) has been used to describe the ideal government.

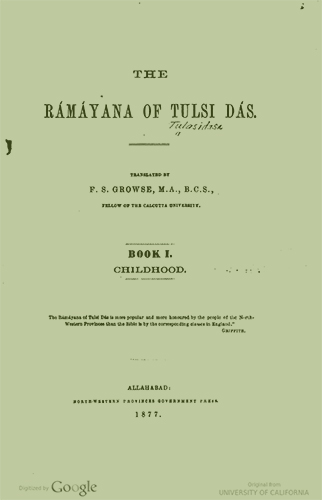

The most famous version of the Ramayana is the Sanskrit composition of Valmiki known as Valmiki’s Ramayana. It has the status of a sacred text and is highly revered. It is also a masterpiece of Sanskrit literature. There were many versions of the Ramayana composed subsequently, both in Sanskrit and other languages. Some became more popular than others, but one is justified to say that after Valmiki’s Ramayana, the version that is most famous is the Ramacaritamanasa created in the Awadhi dialect of Hindi by Tulasidasa in the 16th century. In fact, Tulasidasa’s Ramayana quickly garnered wide popularity and its recitation became part of the worship service of many sects and religious traditions of Vaishnava Hinduism, especially after the introduction of the printing press in the early 19th century. Its communal recital, often set to a distinctive tune, continues to this day. Tulasidasa was himself an ardent devotee of Lord Rama and in expressing his love and reverence for the divine incarnation in beautiful poetry he managed to create one of the greatest poetic works of Hindi literature.

Tulasidasa was born in the region of Avadh in what is now eastern Uttar Pradesh in modern India. There is disagreement about his date of birth, but scholars generally consider it to be around 1532 CE. Traditional accounts state that he was a Brahmin by caste and was initiated into a mystic and ascetic lineage devoted to the loving worship of God through the incarnation of Rama. He is supposed to have spent time as a student with various sages and teachers in Banaras where he learnt the classical Sanskrit texts as well as Vaishnava scriptures. He decided to compose a Ramayana in Awadhi for the edification of the general population, and thus, composed the Ramacaritamanasa, The Lake of the Deeds of Rama. He composed a number of other works as well but the Ramacaritamanasa remained his magnum opus. He died in 1623 in Banaras.

When he set about composing the Ramacaritamanasa, Tulasidasa had a long tradition of composing Ramayanas to look up to going all the way back to Valmiki. At the same time, he was well aware of the literary styles and compositions of his own time when the beginnings of Hindi literature had already been made and a corpus and canon were slowly but steadily evolving. Tulasidasa was to leave his mark on this evolution.

Tulasidasa followed the conventions of chanda prosody that had been the hallmark of Sanskrit poetry and was also followed in other languages, especially for works in Aparbhramsa, the medium of literary production before the rise of Hindi. He also might have been inspired by the metrical structure of the premakhya, a genre of love ballads popular in his days, in creating the basic form for the Ramacaritamanasa. The work is composed in regular arrangements of caupais (quatrains) and dohas (couplets) and he used a different meter for every section of the work.

Tulasidasa used his considerable literary skills to retell the story of the struggles and ordeals of Lord Rama, his brother Lakshmana, his wife Sita, and his devoted disciple, the monkey god, Hanumana, as they faced family feuds, exile, and an epic war against the demon king, Ravana, who had kidnapped Sita, until they returned victorious and vindicated to their capital, Ayodhya, to establish a just and prosperous kingdom.

Ramacaritamanasa is not just a skilled literary retelling of the ancient epic in the charming Awadhi dialect but is redolent with Tulasidasa’s own loving devotion to Lord Rama which seeps through its every line. Perhaps that is why millions of devotees of Lord Rama continue to use it to express their own love and devotion in prayer.

Hindi has been taught UC Berkeley since the late 1960s. Currently, there are two Hindi lecturers. Usha Jain has authored books on Hindi language instruction, including Introductin to Hindi Grammar (1995), Intermediate Hindi Reader (1999), and, Advanced Hindi Grammar (2007). The other instructor is Dr. Nora Melnikova whose interests include second language teaching, modern Theravada Buddhism, and the Early Modern languages and literature of North India. She has also translated Mirabai’s medieval Hindi poems and Erich Frauwallner’s History of Indian Philosophy into Czech.

Contribution by Adnan Malik

Curator and Cataloger for the South Asia Collection

South/Southeast Asia Library

Title: Rāmacaritamānasa

Title in English: The Rámáyana of Tulsi Dás

Authors: Tulasīdāsa, 1532-1623.

Imprint: Allahabad : North-western Provinces Government Press, 1877.

Edition: Indo-European, Indo-Aryan

Language: Hindi

Language Family: Indo-European, Indo-Iranian

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (UC Berkeley)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006125797

Other online editions:

- Recitation of text on YouTube (accessed 11/19/19)

- The Rámáyana of Tulsi Dás. Rev. and illustrated. Allahabad : North-western Provinces Government Press, 1883. (Internet Archive)

- The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki : An Epic of Ancient India / introduction and English translation by Robert P. Goldman ; annotation by Robert Goldman and Sally J. Sutherland. Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, ©1984- ©2017. (Project Muse – UCB only)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- The Rámáyana of Tulsi Dás. Allahabad : North-western Provinces Government Press, 1877.

- The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki : An Epic of Ancient India / introduction and English translation by Robert P. Goldman ; annotation by Robert Goldman and Sally J. Sutherland. Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, ©1984- ©2017.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Urdu

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

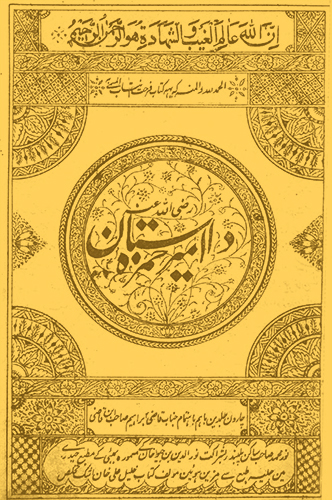

The dastan is a genre of oral and prose narrative that initially developed in Persian but then spread to other languages influenced by the Persian literary tradition. To be sure, oral tale-telling is hardly unique to Persian or Persian-influenced languages, but the dastan has some unique literary features that make it stand out. Dastans often have very long story lines that can be embellished and stretched even further through detailed descriptions of characters, events, and locations. With their dramatic narratives, dastans are primarily meant for oral performances and enjoying the richness of language and literary traditions.

One of the most popular dastans in South Asia was Dastan-i Amir Hamzah (the Dastan of Amir Hamzah). It had its origins in 11th century Iran, but eventually made its way to India where it developed many versions in Persian. Dastan-i Amir Hamzah was popular at the Mughal court where Emperor Akbar was an avid fan.

The hero of the dastan is Hamzah, an uncle of the Prophet Muhammad, who is depicted as a great warrior and supporter of his nephew in early Islamic sources. The adventures of the Hamzah of the dastan, however, are based on fantasy. In the dastan, Amir Hamzah is begged by the wise vizier of Naushirvan, the king of Persia, to help the latter fight his enemies. The gallant Hamzah agrees and fights many battles. He also falls in love with Naushirvan’s daughter, Mahnigar, and seeks her hand in marriage, which requires him to fight more battles and vanquish more enemies. He is accompanied in his travails by his trusted companions, the laconic and serious Muqbil, skilled in archery, and the dishonest but loyal ‘Amr the ‘Ayyar. ‘Ayyars were skilled in espionage and disguises and were notorious for their trickery and special equipment (much like the ninjas). ‘Amr is not only an exceptionally talented ‘ayyar but is extremely greedy even by the low standards of his profession.

As luck would have it, before he could wed Mahnigar, Amir Hamzah is wounded in a battle and is rescued by Shahpal, the king of paris (fairies) who requests that Hamzah help him regain his kingdom in the magical world of Qaf that had been overtaken by demons. Consequently, Amir Hamzah spends eighteen years in the supernatural world of Qaf fighting sorcerers and demons, who can cast such potent spells they can create entire worlds of illusion called tilism. Amir Hamzah and his companions can never be sure whether they are operating in a tilism or in the world of Qaf (which itself is magical) and had to resort to all sorts of ways to break the spells, often with help from saintly figures. Incidentally, an alternative title for the dastan, especially its version based on selections from earlier ones is, Tilism-i Hosh Ruba, The Sense-stealing Tilism.

After eighteen years of adventures, Amir Hamza is finally able to pay his debt to Shahpal. He returns to marry Mahnigar. They have a son named Qubad, but Amir Hamza’s adventures do not end there. He is compelled to fight other enemies and demons until he is called back to Arabia by his nephew, the Prophet Muhammad, to help him fight the enemies of Islam.

When, starting in the 16th century, Urdu became a medium of literary production, dastans began to be composed in it as well. This included versions of Dastan-i Amir Hamzah that were popular enough to have professional story-tellers, called dastan-go or qissah-khvan. Owing to its popularity and the richness of its language, John Gilchrist, head of the Hindustani Department at Fort William College, Calcutta, commissioned a teacher at the department, Khalil Ali Khan Ashk who was also a dastan-go, to publish a printed version of the dastan. Ashk produced the first printed edition of Dastan-i Amir Hamzah in 1801. This makes it not only the earliest printed edition of the dastan but also one of the earliest printed books in Urdu. Ashk’s version consisted of about 500 pages spread over four volumes. It was published many times in the subsequent decades in Delhi, Lucknow, and Bombay. Many of these editions were published by the famous Munshi Nawal Kishore of Lucknow, who published another version by Abdullah Bilgrami in 1871. By the 1920s, the rise of the novel and changing tastes eclipsed the fortunes of dastans and they fell out of favor.

The edition included here is the 1863 edition of Askh’s version that was published from Bombay.

Urdu has been part of language instruction at UC Berkeley since the late 1950s. UC Berkeley also runs the Berkeley Urdu Language Program in Pakistan (BULPIP) in collaboration with the American Institute of Pakistan Studies. In addition, the Institute for South Asia Studies launched the Berkeley Urdu Initiative in 2011 to further promote the study of Urdu at Cal. The leading light for many of the Urdu-related events and activities is Dr. Gregory Maxwell Bruce, the Urdu language instructor, who joined the Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies in the Fall of 2016.

Contribution by Adnan Malik

Curator and Cataloger for the South Asia Collection

South/Southeast Asia Library

Title: Dāstān-i Amīr Ḥamzah razī Allāh ʻanh

Authors: unknown

Imprint: Bambaʼī : Maṭbaʻ Ḥaydarī, 1280 [1863].

Edition: n/a

Language: Urdu

Language Family:

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (UC Berkeley)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100188630

Other online editions:

- The Romance Tradition in Urdu : Adventures from the Dastan of Amir Hamzah / translated, edited, and with an introduction by Frances W. Pritchett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991. Introductory material from the printed edition (modified and corrected wherever appropriate) and the longer translation of the Bilgrami edition.

- Text of Bigrami/Naval Kishore edition (Rekhta: The Largest Website of Urdu Poetry)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Dāstān-i Amīr Ḥamzah razī Allāh ʻanh. Bambaʼī : Maṭbaʻ Ḥaydarī, 1280 [1863].

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Occitan

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

A Lamartine:

Te consacre Mirèio : es moun cor e moun amo,

Es la flour de mis an,

Es un rasin de Crau qu’emé touto sa ramo

Te porge un païsan.

To Lamartine :

To you I dedicate Mirèio: ‘tis my heart and soul,

It is the flower of my years;

It is a bunch of Crau grapes,

Which with all its leaves a peasant brings you. (Trans. C. Grant)

On May 21, 1854, seven poets met at the Château de Font-Ségugne in Provence, and dubbed themselves the “Félibrige” (from the Provençal felibre, whose disputed etymology is usually given as “pupil”). Their literary society had a larger goal: to restore glory to their language, Provençal. The language was in decline, stigmatized as a backwards rural patois. All seven members of the Félibrige, and those who have taken up their mantle through the present day, labored to restore the prestige to which they felt Provençal was due as a literary language. None was more successful or celebrated than Frédéric Mistral (1830-1914).

Mirèio, which Mistral referred to simply as a “Provençal poem,” is composed of 12 cantos and was published in 1859. Mirèio, the daughter of a wealthy farmer, falls in love with Vincèn, a basketweaver. Vincèn’s simple yet noble occupation and Mirèio’s modest dignity and devotion mark them as embodiments of the country virtues so prized by the Félibrige. Mirèio embarks on a journey to Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, that she might pray for her father to accept Vincèn. Her quest ends in tragedy, but Mistral’s finely drawn portraits of the characters and landscapes of beloved Provence, and of the implacable power of love still linger. C.M. Girdlestone praises the regional specificity and the universality of Mistral’s oeuvre thus: “Written for the ‘shepherds and peasants’ of Provence, his work, on the wings of its transcendant loveliness, reaches out to all men.”[1]

Mistral distinguished himself as a poet and as a lexicographer. He produced an authoritative dictionary of Provençal, Lou tresor dóu Felibrige. He wrote four long narrative poems over his lifetime: Mirèio, Calendal, Nerto, and Lou Pouemo dóu Rose. His other literary work includes lyric poems, short stories, and a well-received book of memoirs titled Moun espelido. Frédéric Mistral won a Nobel Prize in literature in 1904 “in recognition of the fresh originality and true inspiration of his poetic production, which faithfully reflects the natural scenery and native spirit of his people, and, in addition, his significant work as a Provençal philologist.”[2]

Today, Provençal is considered variously to be a language in its own right or a dialect of Occitan. The latter label encompasses the Romance varieties spoken across the southern third of France, Spain’s Val d’Aran, and Italy’s Piedmont valleys. The Félibrige is still active as a language revival association.[3] Along with myriad other groups and individuals, it advocates for the continued survival and flowering of regional languages in southern France.

Contribution by Elyse Ritchey

PhD student, Romance Languages and Literatures

Source consulted:

- Girdlestone, C.M. Dreamer and Striver: The Poetry of Frédéric Mistral. London: Methuen, 1937.

- “Frédéric Mistral: Facts.” The Nobel Prize. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1904/mistral/facts. (accessed 11/12/19)

- Felibrige, http://www.felibrige.org (accessed 11/12/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Mirèio

Title in English: Mirèio / Mireille

Author: Mistral, Frédéric, 1830-1914

Imprint: Paris: Charpentier, 1861.

Edition: 2nd

Language: Occitan with parallel French translation

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Gallica (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k64555655

Other online editions::

- An English version (the original crowned by the French academy) of Frédéric Mistral’s Mirèio from the original Proven̨cal under the author’s sanction. Avignon : J. Roumanille, 1867. HathiTrust

- Mireille, poème provençal avec la traduction littérale en regard. Paris, Charpentier, 1898. HathiTrust

- Mirèio : A Provençal poem. Translated into English by Harriet Waters Preston. London, T.F. Unwin, 1890. Internet Archive (UC Riverside)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Mireille : poème provençal. Traduit en vers français par E. Rigaud. Paris : Librairie Hachette, 1881.

- Mireio : pouemo prouvencau, avec la traduction littérale en regard. Paris : Charpentier, 1888.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Malay/Indonesian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Senandung jiwaku is a selection of poems by Mulyono Saleh published in various Indonesian newspapers and magazines between 1963 and 1976 that he entitled “The Song of My Soul.” The poems show the author’s concerns, love, and hope for his country (Indonesia) and his fellow countrymen, as well as religious reflections. He pays particular attention to marginalized segments of society such as women (mothers and national heroines) and ordinary people like grassroots farmers and fishermen.

Ethnologue lists 719 distinct languages, mostly indigenous, spoken in Indonesia, making it the most linguistically diverse country on the planet.[1] For at least a thousand years, however, Malay has held the position of lingua franca of the maritime region of the great Malay archipelago, which is now divided between Indonesia and Malaysia. The names bahasa Indonesia (“Indonesian language) and bahasa Malaysia (“Malaysian language”) — both standardized varieties of Malay — were introduced in the 20th century to differentiate the two national languages.[2] Indonesia is now the fourth most populous nation in the world. Of its large population, the majority speak Indonesian, making it one of the most widely spoken languages in the world.[3]

The Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies (SSEAS) at UC Berkeley offers both undergraduate and graduate instruction and research in the languages and civilizations of South and Southeast Asia from the most ancient period to the present. Instruction includes intensive training in several of the major languages of the area including Bengali, Burmese, Hindi, Khmer, Indonesian (Malay), Pali, Prakrit, Punjabi, Sanskrit (including Buddhist Sanskrit), Filipino (Tagalog), Tamil, Telugu, Thai, Tibetan, Urdu, and Vietnamese, and specialized training in the areas of literature, philosophy and religion, and general cross-disciplinary studies of the civilizations of South and Southeast Asia.[4] Outside of SSEAS where beginning through advanced level courses are offered in Indonesian, related courses are taught and dissertations produced across campus in Anthropology, Comparative Literature, Ethnic Studies, History, Linguistics, Music, and Political Science (re)examining the rich history and cultures of Indonesia.[5]

Yusmarni Djalius, PhD Student

Lecturer, Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies

Sources consulted:

- Ethnologue: Languages of the World (accessed 11/8/19)

- Dalby, Andrew. Dictionary of Languages: The Definitive Reference to More Than 400 Languages. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998.

- Sneddon, James Neil. The Indonesian Language: Its History and Role in Modern Society. Sydney: UNSW Press, 2003.

- Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies, UC Berkeley (accessed 11/8/19)

- Indonesian (INDONES) – Berkeley Academic Guide (accessed 11/8/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Senandung jiwaku: kumpulan sajak Mulyono Saleh

Title in English: The Song of My Soul

Author: Saleh, Mulyono

Imprint: Bandung : Tarate, 1976.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Malay/Indonesian

Language Family: Austronesian, Malayo-Polynesian

Source: Center for Research Libraries

URL: https://dds.crl.edu/crldelivery/28736

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

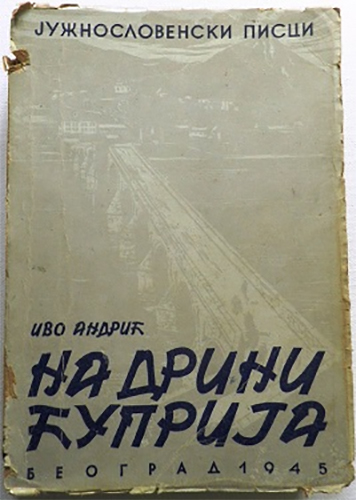

Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

In 1919, following World War I and the Paris Peace Conference, the country later called Yugoslavia came into existence in Southeast Europe. However, the country’s name from 1918 to 1929 was the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. After World War II, this country was renamed the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia in 1946. It included the republics of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro, Slovenia, Macedonia, and the autonomous provinces of Vojvodina and Kosovo. The language that was known as Serbo-Croatian was spoken in nearly all of Yugoslavia. In 1991, in the aftermath of the dissolution of Yugoslavia after a period of protracted civil war, all of these constituent parts eventually became independent. First, Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia-Herzegovina became independent in 1991. Serbia and Montenegro were joined, under the name Yugoslavia in 2003 and under the name Serbia-Montenegro in 2006. Thus Serbia as such became a separate country only in 2006 when Montenegro proclaimed independence. Kosovo proclaimed independence in 2008 with the support of the United States and allies. Slovenian and Macedonian were already separate languages. However, outside the formerly united country, the name Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian (BCS) became accepted to denote three different languages that are nearly identical to each other in grammar and pronunciation. However, there are some significant differences in vocabulary. Bosnian and Croatian use a Latin based script while Serbian uses both this alphabet and the Cyrillic alphabet. The term BCS was in fact established at the Hague tribunal (ICTY), and the legitimacy gained in this way allowed its widespread acceptance.

The study of Serbo-Croatian, later BCS, began at UC Berkeley in the aftermath of World War II. Since then the Library’s collections in these languages have been growing steadily and now represent one of the stronger components of Library’s Slavic collections. At UC Berkeley, the situation dramatically changed with the arrival of Professor Ronelle Alexander in 1978. She has been instrumental in helping the Library build up its exemplary Balkan Studies collections for the last four decades. The diversity of her teaching and research expertise ranges from South Slavic languages (Bulgarian, Macedonian, BCS), literatures of former Yugoslavia, Yugoslav cultural history, South Slavic linguistics, Balkan folklore to East Slavic folklore. Although her primary research accomplishments are in South Slavic linguistics, she has also published research on the most widely known and translated Serbian poet, Vasko Popa, and Yugoslavia’s only Nobel prize winner, the prose writer Ivo Andrić.[1]

It is challenging to find one single work that would represent the complex nature and relationships between Bosnian, Croatian and Serbian. However, one must note that to this day, the Balkans represent a constantly evolving dynamic mosaic of linguistic diversity that shares a relatively compact geographic topos. For this exhibition, I chose one work that theoretically presents a complicated relationship in Balkans—Ivo Andrić’s prize-winning novel Na Drini ćuprija (“The Bridge on the Drina”) published in 1945.

This historical fiction novel by the Yugoslav writer, Ivo Andrić, revolves around the Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge in Višegrad. This bridge is located in Eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina on the Drina River.[2] It was built by the Ottomans in the mid-16th century, and was damaged several times during the wars of the 20th century but each time rebuilt. It was never entirely destroyed and the “original bridge” remains, and is now on the World Heritage List of UNESCO.[3]

The novel chronicles four centuries of regional history, including the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian occupations. The story highlights the daily lives and inter-communal relationships between Serbs and Bosniaks. Bosnian Muslims-Slavs, now also called Bosniaks. Ever since the end of World War II when three major works of Ivo Andrić (The Bridge on the Drina, Bosnian Chronicle, and The Woman from Sarajevo) appeared in print almost simultaneously in 1945. The Woman from Sarajevo has not stood the test of time, though the other two are major works. A later novel, The Damned Yard, is considered much more important. He has been hailed as a major literary figure by both his country’s reading public and by the critics. His reputation soared even higher when he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1961.[4] The Bridge on Drina has been translated into more than 30 languages.

Contribution by Liladhar Pendse

Librarian for East European and Central Asian Studies, Doe Library

Source consulted:

- Ronelle Alexander authored an article on Andric titled “Narrative Voice and Listener’s Choice in the Prose of Ivo Andrić” in Vucinich, W. S. (1995). Ivo Andric Revisited: The Bridge Still Stands. Research Series, uciaspubs/research/92. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8c21m142 (accessed 7/26/19).

- Ronelle, Alexander. “What Is Naš? Conceptions of “the Other” in the Prose of Ivo Andric.” スラヴ学論集 = Slavia Iaponica = Studies in Slavic Languages and Literatures. 16 (2013): 6-36. (accessed 7/26/19)

- UNESCO World Heritage. “Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge in Višegrad.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre, whc.unesco.org/en/list/1260.

- Moravcevich, Nicholas. “Ivo Andrić and the Quintessence of lpendTime.” The Slavic and East European Journal, vol. 16, no. 3, 1972, pp. 313–318. (accessed 7/26/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Na Drini ćuprija/ На Дрини ћуприја

Title in English: The Bridge on the Drina

Author: Andrić, Ivo, 1892-1975.

Imprint: Sarajevo: Svjetlost, 1946.

Edition: 1st

Language: Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian (BCS)

Language Family: Indo-European, Slavic

Source: Biblioteka Elektronskaknjiga

URL: https://skolasvilajnac.edu.rs/wp-content/uploads/Ivo-Andric-Na-Drini-cuprija.pdf

Other online editions::

- The Bridge on the Drina. Translated from the Serbo-Croat by Lovett F. Edwards. London: George Allen And Unwin Ltd., [c.1945]. Internet Archive

- In Cyrillic: https://www.scribd.com/doc/185963009/Ivo-Andric-Na-Drini-Cuprija-Cirilica

- Audiobook: https://archive.org/details/IvoAndricNaDriniCuprija4Dio

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Na drini ćuprija. Vishegradska khronika. Sarajevo: Svjetlost, 1946.

- The Bridge on the Drina / Ivo Andrić ; translated from the Serbo-Croat by Lovett F. Edwards ; with an introd. by William H. McNeill. Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 1977.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Yiddish

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

דער גרויסער וועלט-פּראָגרעס האָט זיך אַהין אַרייַנגעכאַפט און האָט איבערגעדרייט די שטאָט מיטן קאַָפּ אַראָפּ, מיט די פֿיס אַרויף.

The great progress of the world has reached Kasrilevke and turned it topsy-turvy.

– From narrator’s foreword to the Kasrilevke stories (1919)

אַיין אַיינשרומפּעניש! ווען האָט געקאָנט ארויס דער צאַפּען, אַיינגעזונקען זאָל ער ווערען? … אַ, ברענען זאָלסט דו, שלים־מזל, אויפ’ן פייער!

און גרונם … דערלאַנגט דעם אַ רוק מיט’ן בייטש־שטעקעל אין זייט אַריין. דאָס פערדעל טהוט אַ פּינטעל מיט די אויגען, לאָזט־אַראָפּ די מאָרדע, קוקט אָן אַ זייט און טראַכט זיךְ׃ פאַר וואָס קומט מיר, אַשטייגער, אָט דער זעץ? גלאַט גענומען און געבוכעט זיךְ! ס’איז ניט קיין קונץ נעמען אַ פערד, אַ שטומע צונג, און שלאָגען איהם אומזיסט און אומנישט!

The driver of the wagon with the water barrel was beside himself! “An empty barrel! … May my helper shrivel up! How could that plug, may it sink into the earth, have come out? May you burn up, wretch that you are!” The last remark was addressed to the little horse, as he struck it with the whip handle. The horse blinked, lowered its chin, and looked aside, thinking, “What have I done to deserve this whack? It’s no trick, you know, to hit a dumb animal for no reason whatsoever.”

– From the story “Fires”

Yiddish is the thousand-year-old language of European (Ashkenazic) Jews. Written from right to left in Hebrew characters, it is derived from German and includes many Hebraic and Slavic elements. It is used for everyday purposes as well as for a rich variety of religious and secular literature, ranging from medieval times to the 21st century. Most Yiddish users were annihilated during the Holocaust of World War II, yet the language continues to thrive in the United States, Israel, and Europe.

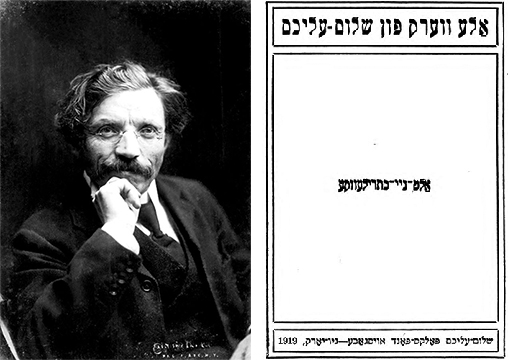

Arguably the best-known Yiddish writer, Sholem Aleichem (Sholem Rabinovich, Ukraine 1859 – United States 1916) was a founding father of modern Yiddish literature. A supreme humorist, he created the literary persona of “Sholem Aleichem” and tapped into the energies of the Eastern European spoken Yiddish idiom. In a variety of genres, he invented modern Jewish archetypes, myths, and fables of unique imaginative power and universal appeal. Sholem Aleichem’s “Tevye” stories provided the basis of the popular mid-20th century musical Fiddler on the Roof. He founded the Folks-bibliotek publishing house (Kiev, 1888) to encourage writers he admired, and identify new talent. In his satirical, yet warm Kasrilevke stories of the 1900s, he created the quintessential fictional shtetl. Its poverty-stricken residents aspired to modernity. Though plagued by backwardness, they continued to dream of redemption.

Following the death in 1916 of the beloved Sholem Aleichem, multi-volume editions of his collected works were published widely. This 1919 edition is printed in the Yiddish spelling prevalent at the time, with transliterations of Germanic linguistic elements; this was meant to help “legitimize” Yiddish (then considered a “jargon”). These transliterations are not used in modern standardized Yiddish orthography. The story “Fires,” from which this selection is taken, underlines the actual lack of progress in the fictional town of Kasrilevke, which prides itself on striving for modernity. The aside, giving voice to the abused horse in the midst of this municipal crisis, is typical of the creative yet plainspoken genius which made Sholem Aleichem so popular.

While the number of native speakers of Yiddish continues to dwindle, Yiddish at Berkeley is thriving. In addition to the esteemed annual conference on Yiddish Culture, we have a wide range of courses dealing with the life and culture of Ashkenazic Jewry, a diverse faculty committed to the preservation and scholarly investigation of Yiddish, and an ever-growing number of students who are pursuing academic futures exploring Jewish culture in the traditional languages of the Jewish people. Students interested in Yiddish at Cal can pursue their interests in the departments of German, Comparative Literature, History, or through the program in Jewish Studies.

Contribution by Yael Chaver

Lecturer in Yiddish, Department of German

Title: Alṭ-nay-Kas̀rileṿḳe

Title in English: Old-New Kasrilevke

Author: Sholem Aleichem, 1859-1916

Imprint: Nyu-Yorḳ : Shalom-ʻAlekhem folḳs-fond, 1919.

Edition: in Ale Verk, Sholom Aleichem

Language: Yiddish

Language Family: Indo-European, Germanic

Source: The Internet Archive (Yiddish Book Center)

URL: https://archive.org/stream/nybc200084

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Sholem, Aleichem. Alṭ-nay-kas̀rileṿḳe. Nyu-Yorḳ: Shalom-ʻAlekhem folḳs-fond, 1919.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Irish

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

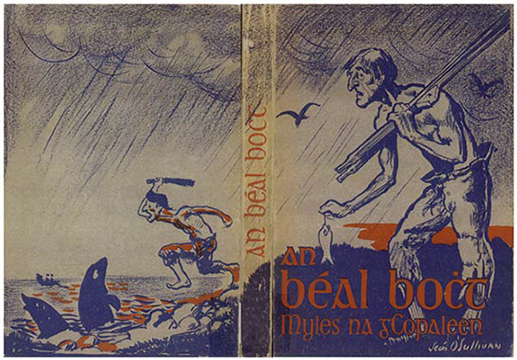

An Béal Bocht (1941), or The Poor Mouth, written by Brian O’Nolan (Ó Nualláin) under the pseudonym Myles na gCopaleen, is one of the most famous Irish language novels of the 20th century. O’Nolan, who most famously published works such as At-Swim-Two-Birds and The Third Policeman under the name Flann O’Brien, wrote in both English and Irish as a journalist and author.

O’Brien takes up the subject of the Irish Literary Revival, a movement in the early 20th century spearheaded by such figures as Lady Gregory and W.B. Yeats who tried to repopularize the Irish folklore and raise the ‘language question’ of Ireland. He simultaneously parodies the genre of Gaeltacht autobiography, autobiographies written in Gaelic that emphasize rural life in Ireland, such as An t-Oileánach (The Islandman) by Tomás Ó Criomhthain and Peig by Peig Sayers, and critiques aspects of the revival.

An Béal Bocht begins with the birth of the narrator, Bónapárt Ó Cúnasa, and follows his life in Corca Dorcha, an impoverished town in the west of Ireland. The town’s rurality attracts the elite from Dublin in search of ‘authentic’ Irishness. Corca Dorcha certainly fits the description — it never stops raining, it’s extremely remote, and crucially, everybody speaks only Irish. The large numbers of visitors from Dublin insist that they love the Irish language, and that one should always speak Irish, about Irish, but ultimately they find Corca Dorcha to be too poor, too rainy, and ironically, too Irish. The very authenticity they sought drives them away to bring their search for authenticity elsewhere.

An Béal Bocht is regarded as a masterful satire, deftly critiquing the genre, the Dublin elite who supposedly supported Irish language revival but avoided rural realities, and the state’s failure to maintain authentic Gaeltacht cultures. The title comes from the Irish expression — ‘putting on the poor mouth’ — which means to exaggerate the direness of one’s situation in order to gain time or favour from creditors. In the novel, there is also the repeated phrase, “for our likes will not be (seen) again,” taken directly from An t-Oileánach.

For more than a century, UC Berkeley has been a locus for the study of Irish culture, language, and literature. Faculty from the departments of English, Rhetoric, Linguistics, and History participate teach courses in Irish and Welsh language and literature (in all their historical phases), and in the history, mythology, and cultures of the Celtic world.[1] The Celtic Studies Program offers the only undergraduate degree in Celtic Studies in North America. Following a visit by President Michael Higgins in 2016 to foster relationships between Irish universities and UC Berkeley, the campus’s Institute of European Studies launched the Irish Studies Program.[2] Flann O’Brien’s works are taught in UC Berkeley classes such as Modern Irish Literature and the English Research Seminar: Flann O’Brien and Irish Literature.

Contribution by Taylor Follett

Literatures and Digital Humanities Assistant, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Celtic Studies Program, UC Berkeley (accessed 10/1/19)

- Irish Studies Program, Institute of European Studies, UC Berkeley (accessed 10/1/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: An Béal Bocht

Title in English: The Poor Mouth

Author: Myles, na gCopaleen (O’Brien, Flann, 1911-1966)

Imprint: Baile Áṫa Cliaṫ : An Press Náisiúnta, 1941.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Irish

Language Family: Indo-European, Celtic

Source: The Internet Archive (Mercier Press)

URL: https://archive.org/details/FlannOBrienAnBalBochtCs

Other online resources:

- Research guide to Flann O’Brien (UC Berkeley Library)

- Corpus of Electronic Texts (CELT)

- “Cruiskeen Lawn,” Myles na gCopaleen’s newspaper column in Irish Times (1859-2011) and Weekly Irish Times (1876-1958) via Proquest Historical Newspapers (UCB Only)

- Irish poet Louis de Paor speaking (in Irish) discusses An Béal Bocht,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vyIQI_huU9g.(accessed 6/18/19)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- O’Brien, Flann. An béal boċt: Nó, an milleánach : Droċ-sgéal ar an droċṡaoġal curta i n-eagar le. Dublin: Eagrán Dolmen, 1964.

- O’Brien, Flann. Translated into English by Patrick C. Power; illustrated by Ralph Steadman. The Poor Mouth: A Bad Story About the Hard Life. New York: Viking Press, 1974.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Vietnamese

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

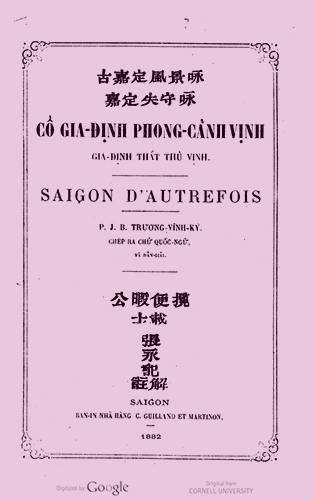

In the 17th century, French Catholic missionaries employed the Roman alphabet to devise a unique orthography for the Vietnamese language. This was the first time in world history that an alphabet represented distinctions in tone.[1] This specially developed Latin script or quốc ngữ, with its double diacritics, coexisted with hán nôm — the Vietnamese adaptation of Chinese script — for three centuries before triumphing under Colonial rule.[2] Scholar Trương Vĩnh Ký (Pétrus Ky) rewrote and annotated this rare work of poetry in romanized Vietnamese toward the end of the 19th century featured here in its original version of the “rhyme-prose” in hán nôm script. It describes many interesting landscapes and social life customs in Gia Dinh (Hồ Chí Minh City) today.

The Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies (SSEAS) at UC Berkeley offers both undergraduate and graduate instruction and research in the languages and civilizations of South and Southeast Asia from the most ancient period to the present. Instruction includes intensive training in several of the major languages of the area including Bengali, Burmese, Hindi, Khmer, Indonesian (Malay), Pali, Prakrit, Punjabi, Sanskrit (including Buddhist Sanskrit), Filipino (Tagalog), Tamil, Telugu, Thai, Tibetan, Urdu, and Vietnamese, and specialized training in the areas of literature, philosophy and religion, and general cross-disciplinary studies of the civilizations of South and Southeast Asia.[3] Outside of SSEAS beginning through advanced level courses are offered in Vietnamese, related courses are taught and dissertations produced across campus in Asian American Studies, Comparative Literature, Ethnic Studies, Folklore, French, History, Linguistics, and Political Science (re)examining the rich history and culture of Vietnam.[4] UC Berkeley’s Center for Southeast Asia Studies is also the editorial home of the Journal of Vietnamese Studies, published by the University of California Press.[5]

Contribution by Hanh Tran

Lecturer, Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies

Virginia Shih

Curator for the Southeast Asia Collection, South/Southeast Asia Library

Sources consulted:

- Garry, Jane, and Carl R. G. Rubino. Facts About the World’s Languages: An Encyclopedia of the World’s Major Languages, Past and Present. New York: H.W. Wilson, 2001.

- Dalby, Andrew. Dictionary of Languages: The Definitive Reference to More Than 400 Languages. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998.

- Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies, UC Berkeley (accessed 10/1/19)

- Vietnamese (VIETNMS) – Berkeley Academic Guide (accessed 10/1/19)

- Journal of Vietnamese Studies. Berkeley, CA. University of California Press, 2006-.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: C̉ô Gia-định phong-cảnh vịnh. Gia-định th́ât thủ vịnh. Saigon d’autrefois.

Title in English: [Saigon Bay Scene. Saigon of Old]

Author: Trương, P. J. B. Vĩnh Ký (Pétrus Jean-Baptiste Vĩnh Ký), 1837-1898.

Imprint: Saigon, C. Guilland et Martinon, 1882.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Vietnamese

Language Family: Austroasiatic, Mon-Khmer

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (Cornell University)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100620763

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Chichewa

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

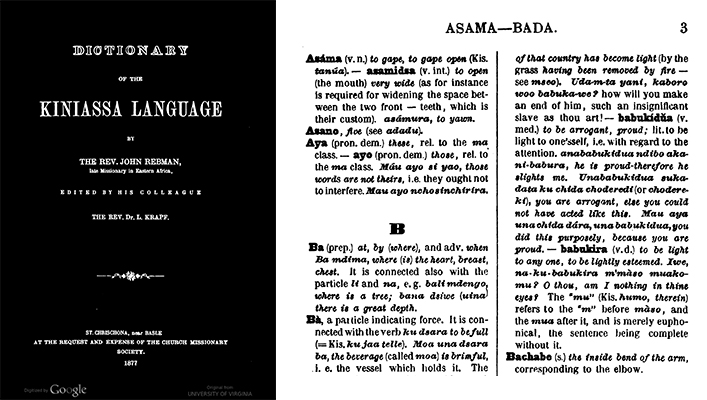

“My study of the Kiniassa was to me such a continual intellectual feast, that days and weeks fled so quickly as I never remembered they had done before, and it was with great reluctance that I tore myself from it when we had to get ready for our voyage to Aden.”

— Reverend John Rebman

With over 2,000 vernacular languages, sub-Saharan Africa includes approximately one-third of the world’s languages.[1] Many of these will likely disappear in the next hundred years, displaced by dominant regional languages like Chichewa. Also known as Chinyanja or Kiniassa, Chichewa is spoken in west-central and southwest Africa. In total, the language claims nearly 10 million speakers across the region. It is an official language — along with English — in Malawi and is officially recognized in Zambia and Mozambique where it is known as Nyanja. Chichewa is part of the Bantu branch of the larger Niger-Congo phylum. Linguistics and archaeologists suggest that these languages began in the grasslands of northwestern Cameroon and north-eastern Nigeria over two thousand years ago and spread across central and southern Africa through a combination of migration and conquest.[2]

The Dictionary of the Kiniassa Language, compiled by the reverend Johannes Rebmann brom 1853-54 and posthumously published in 1877, was the first extensive written record of the Chichewa language. It is representative of the fairly prolific publishing output of European missionaries — principally religious (bible translations, hymn books, etc.) or grammar and vocabulary texts — during the early colonial period.

These types of texts — especially the grammar and vocabulary texts — can offer a unique vantage point from which to view the imaginative nature of work that is otherwise often viewed as static. For example, in works of comparative religion, scholars can use these creative texts to gain insight into how missionaries grappled with words to accurately define religious concepts such as “sin” to serve their proselytizing purposes. Ultimately, old words were re-defined or altogether new words were crafted to meet the present need.

Contribution by Adam Clemons

Librarian for African and African American Studies, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Moseley, Christopher, and Alexandre Nicolas. Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. Paris: UNESCO, 2010.

- Dalby, Andrew. Dictionary of Languages: The Definitive Reference to More Than 400 Languages. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Dictionary of the Kiniassa Language

Author: Rebman, John, 1820-1876.

Imprint: St. Chrischona: Church Missionary Society, 1877.

Edition: 1st

Language: Chichewa

Language Family: Niger-Congo

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Virginia)

URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uva.x000079094

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Dictionary of the Kiniassa language, by the Rev. John Rebman, edited by his colleague, the Rev. Dr. L. Krapf. St. Chrischona, near Basle, Switzerland, The Church missionary society, 1877.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Arabic

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

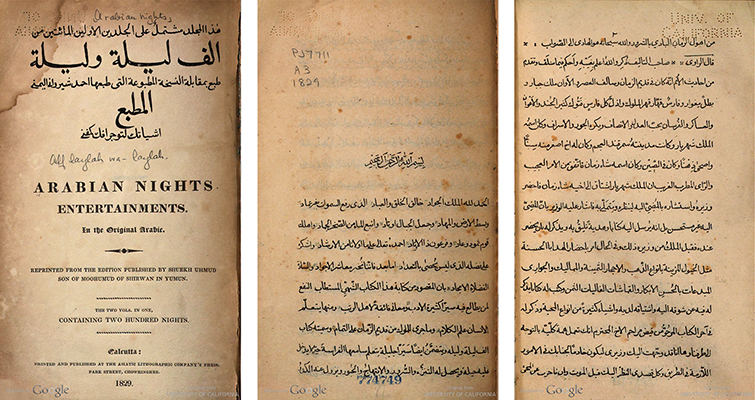

Arabian Nights or One Thousand and One Nights (Arabic: ألف ليلة وليلة, Alf Laylah wa-Laylah) is a multicultural collection of stories. According to The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia, “No other work of fiction of non-Western origin has had a greater impact on Western culture than the Arabian Nights.”[1] “[P]reserved in its Arabic compilation, the collection is rooted in a Persian prototype that existed before the ninth century CE, and some of its stories may date back even further to the Mesopotamian, ancient Indian, or ancient Egyptian cultures.”[2] This classic, like numerous other Arabic works, reveals the great influence of the Arabic legacy on other cultures.

The first Arabic manuscript of Arabian Nights dates back to the 15th century, which was first translated into French in 1704 by the French orientalist François Galland, followed by the English edition in 1706. Since then, Arabian Nights has been translated and reproduced in numerous languages and formats. Stories from Arabian Nights have also been represented in other art forms, such as drama and films to mention a few. Aladdin, The Thief of Bagdad, and Adventures of Sinbad are three examples of famous films.

Arabic became an essential language for human knowledge in the medieval centuries during the bright period of the Islamic civilization, when Muslim scholars vastly contributed to knowledge and science in many fields: algebra, geography, medicine, social sciences, astronomy and many more.[3] The impact of the Arabic language and Muslim scholars’ contribution is seen until today in different disciplines and, most definitely, in languages worldwide. In English, for instance, algebra, chemistry, and algorithm are originally Arabic words.

As the native language in more than 20 Arab nations and one of the official languages in many other countries, Arabic is one of the most spoken languages in the world after Chinese, Spanish, and English; hence, it is one of the six languages recognized by the United Nations. Arabic is one of the Semitic languages which, like Hebrew, are written from right to left. Most importantly, Arabic is the language of the Quran, the holy book of Islam. Therefore, it is the language of daily prayers around the world regardless of the Muslims’ native languages.

According to the Modern Language Association’s enrollment data for 2016, Arabic is among the top 10 languages taught in the US with 31,554 enrollments in 2016 compared to 24,010 enrollments in 2006.[4] This number includes students enrolled in classes for standard Arabic, as well as the Arabic language classes focusing on various dialects such as Egyptian colloquial Arabic, Shami (Syrian, Lebanese, and Palestinian/Jordanian) colloquial Arabic, Moroccan and North African colloquial Arabic, and Khaliji Arabic in the Persian Gulf Region.

At UC Berkeley, Arabic is one of the languages of emphasis for the major in Near Eastern Languages and Literature offered by the Department of Near Eastern Studies (NES). Students who major and minor in Arabic learn about the peoples, cultures, and histories of the Arabic speaking world besides the language. NES offers all levels of Arabic language courses: 1A and 1B (elementary), 20A, 20B and 30 (intermediate), and 100A and 100B (advanced), and an intensive summer program. Upper division courses range from the study of colloquial Arabic, to classical prose and poetry, to historical, religious and philosophical texts, to survey of and seminars in both classical and modern Arabic literature.[5]

Contribution by Mohamed Hamed

Middle Eastern & Near Eastern Studies Librarian, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Leeuwen, R. van, Marzolph, U., & Wassouf, H. (2004). Introduction. In The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia (p. xxiii). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

- Ibid.

- Ignacio Ferrando. ‘History of Arabic’ in Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Ed. Lutz Edzard et al. Brill Reference Online, 2019. (accessed 9/27/19)

- Modern Language Association of America. Enrollments in Languages Other Than English in United States Institutions of Higher Education, Summer 2016 and Fall 2016: Final Report (June 2019). (accessed 9/27/19)

- Arabic (ARABIC) – Berkeley Academic Guide (accessed 9/27/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Alf laylah wa-laylah

Title in English: Arabian Nights

Author: unknown

Imprint: Calcutta : The Asiatic Lithographic Company, 1829.

Edition: n/a

Language: Arabic

Language Family: Central Semitic

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (UC Berkeley)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100639014

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)