Tag: BL Indo-European Slavic

Polish

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Modern day academics and literary scholars have spent considerable time studying the phenomenon related to the use of literature to create national heroes. While, the use of literary forms gives a particular author the means to incorporate the cultural sensitivities, the literary forms that evolve are functions of the society and time in which a particular author was born. Pan Tadeusz as an epic poem is not an exception but reinforces the stereotypes of a particular period through the poetics of Adam Mickiewicz.

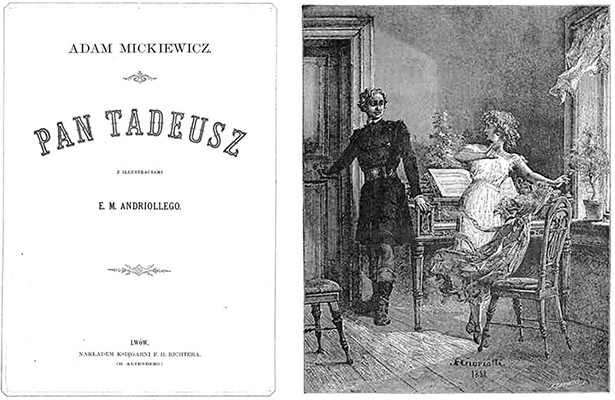

Adam Mickiewicz was born in Nowogródek of the Grand Dutchy of Lithuania in 1798. Nowogródek is today known as Novogrudok and is located in Republic of Belarus. He was educated in Vilnius, the capital of today’s Lithuania. He is recognized as the national literary hero of Poland and Lithuania. However, most of his adulthood was spent in exile after 1829. In Russia, he traveled extensively and was a part of St. Peterburg’s literary circles.[1] There have been several works that track the trajectory of Mickiewicz’s travel and exile. Pan Tadeusz reflects the realities of the partition of the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth from the perspective of the poet. The drive for liberty and freedom were indeed two traits of Adam Mickiewicz’s life journey that cannot be ignored. The synopsis of the story has been summarized below. Also of interest are the illustrations to accompany the storyline. One prominent illustrator was his compatriot Michał Elwiro Andriolli (1836-1893).[2]

Pan Tadeusz is the last major work written by Adam Mickiewicz, and the most known and perhaps most significant piece by Poland’s great Romantic poet, writer, philosopher and visionary. The epic poem’s full title in English is Sir Thaddeus, or the Last Lithuanian Foray: a Nobleman’s Tale from the Years of 1811 and 1812 in Twelve Books of Verse (Pan Tadeusz, czyli ostatni zajazd na Litwie. Historia szlachecka z roku 1811 i 1812 we dwunastu księgach wierszem). Published in Paris in June 1834, Pan Tadeusz is widely considered the last great epic poem in European literature.

Drawing on traditions of the epic poem, historical novel, poetic novel and descriptive poem, Mickiewicz created a national epic that is singular in world literature.[3] Using means ranging from lyricism to pathos, irony and realism, the author re-created the world of Lithuanian gentry on the eve of the arrival of Napoleonic armies. The colorful Sarmatians depicted in the epic, often in conflict and conspiring against each other, are united by patriotic bonds reborn in shared hope for Poland’s future and the rapid restitution of its independence after decades of occupation.

One of the main characters is the mysterious Friar Robak, a Napoleonic emissary with a past, as it turns out, as a hotheaded nobleman. In his monk’s guise, Friar Robak seeks to make amends for sins committed as a youth by serving his nation. The end of Pan Tadeusz is joyous and hopeful, an optimism that Mickiewicz knew was not confirmed by historical events but which he designed in order to “uplift hearts” in expectation of a brighter future.

The story takes place over five days in 1811 and one day in 1812. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had already been divided among Russia, Prussia and Austria after three traumatic partitions between 1772 and 1795, which had erased Poland from the political map of Europe. A satellite within the Prussian partition, the Duchy of Warsaw, had been established by Napoleon in 1807, before the story of Pan Tadeusz begins. It would remain in existence until the Congress of Vienna in 1815, organized between Napoleon’s failed invasion of Russia and his defeat at Waterloo.

The epic takes place within the Russian partition, in the village of Soplicowo and the country estate of the Soplica clan. Pan Tadeusz recounts the story of two feuding noble families and the love between the title character, Tadeusz Soplica, and Zosia, a member of the other family. A subplot involves a spontaneous revolt of local inhabitants against the Russian garrison. Mickiewicz published his poem as an exile in Paris, free of Russian censorship, and writes openly about the occupation.

The poem begins with the words “O Lithuania”, indicating for contemporary readers that the Polish national epic was written before 19th century concepts of nationality had been geopoliticized. Lithuania, as used by Mickiewicz, refers to the geographical region that was his home, which had a broader extent than today’s Lithuania while referring to historical Lithuania. Mickiewicz was raised in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the multicultural state encompassing most of what are now Poland, Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine. Thus Lithuanians regard the author as of Lithuanian origin, and Belarusians claim Mickiewicz as he was born in what is Belarus today, while his work, including Pan Tadeusz, was written in Polish.”

Polish is a prominent member of the West Slavic language group. It is spoken primarily in Poland and serves as the native language of the Poles who live in various parts of world including the United States. Poles have been involved in the history of the American Revolution from early on. One such example is that of Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko who was an engineer and fought on the side of American revolution.

At UC Berkeley, Polish language teaching has been a major part of the portfolio of the Slavic languages that are being taught at the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures. This department was home to UC Berkeley’s only faculty member, Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz (1911-2004), to have ever received the prestigious Nobel Prize in Literature.[4] The tradition of Milosz is continued today in the same department by Professor David Frick. Professor John Connelly in the History department is another luminary scholar of Polish history.

Marie Felde, who reported on his death in the UC Berkeley News Press release on 14th August 2004 noted, “When Milosz received the Nobel Prize, he had been teaching in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literature at Berkeley for 20 years. Although he had retired as a professor in 1978, at the age of 67, he continued to teach and on the day of the Nobel announcement he cut short the celebration to attend to his undergraduate course on Dostoevsky.”[5]

Contribution by Liladhar Pendse

Librarian for East European and Central Asian Studies, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Adam Mickiewicz, 1798-1855; In Commemoration of the Centenary of His Death in UNESDOC DIGITAL LIBRARY (accessed 2/21/20)

- Andriolli : Ilustracje do “Pana Tadeusza” (accessed 2/21/20)

- “Pan Tadeusz – Adam Mickiewicz,” Culture.pl (accessed 2/21/20)

- The Nobel Prize in Literature 1980, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1980/summary (accessed 2/21/20)

- UC Berkeley News (August 14, 2004), https://www.berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/2004/08/15_milosz.shtml (accessed 2/21/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Pan Tadeusz

Title in English: Pan Tadeusz or The Last Foray in Lithuania

Author: Mickiewicz, Adam, 1798-1855.

Imprint: Lwów : Nakładem Księgarni F.H. Richtera (H. Altenberg) , [1882?].

Edition: unknown

Language: Polish

Language Family: Indo-European, Slavic

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)

URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112046983406

Other online editions:

- Pan Tadeusz; czyli, Ostatni zajazd na Litwie. Historja szlachecka z r. 1811 i 1812, we dwunastu ksiegach, wierszem, przez Adama Mickiewicza … Wydanie Alexandra Jelowickiego; s popiersiem autora. 1st edtion. Paryz, 1834. (Gallica – Bibliothèque nationale de France)

- Pan Tadeusz; czyli, Ostatni zajazd na Litwie. Historja szlachecka z r. 1811 i 1812, we dwunastu ksiegach, wierszem, przez Adama Mickiewicza … Wydanie Alexandra Jelowickiego; s popiersiem autora. 1st edtion. Paryz, 1834. (Project Gutenberg)

- Pan Tadeusz czyli ostatni zajazd na Latwie. Warszawa : Fundacja Nowoczesna Polska, 2016.

- Pan Tadeusz or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Story of Life Among Polish Gentlefolk in the Years 1811 and 1812 in Twelve Books. Translated into English by George Rapall Noyes. London : Dent ; New York : Dutton, 1917. (Project Gutenberg )

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Pan Tadeusz; czyli, Ostatni zajazd na Litwie. Historja szlachecka z r. 1811 i 1812, we dwunastu ksiegach, wierszem, przez Adama Mickiewicza … Wydanie Alexandra Jelowickiego; s popiersiem autora. 1st edition. Paryz, 1834.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Old Church Slavonic

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

According to the late Slavic linguist Horace Gray Lunt, “Slavonic or OCS is one of the Slavic languages that was used in the various geographical parts of the Slavic world for over two hundred years at the time when the Slavic languages were undergoing rapid, fundamental changes. Old Church Slavonic is the name given to the language of the oldest Slavic manuscripts, which date back to the 10th or 11th century. Since it is a literary language, used by the Slavs of many different regions, it represents not one regional dialect, but a generalized form of early Eastern Balkan Slavic (or Bulgaro-Macedonian) which cannot be specifically localized. It is important to cultural historians as the medium of Slavic Culture in the Middle Ages and to linguists as the earliest form of Slavic known, a form very close to the language called Proto-Slavic or Common Slavic which was presumably spoken by all Slavs before they became differentiated into separate nations.”[1]

At UC Berkeley, OCS has been taught regularly on a semester basis. Professor David Frick currently teaches it. His course description is as follows, “The focus of the course is straight forward, the goals are simple. We will spend much of our time on inflexional morphology (learning to produce and especially to identify the forms of the OCS nominal, verbal, participial, and adjectival forms). The goal will be to learn to read OCS texts, with the aid of dictionaries and grammars, by the end of the semester. We will discuss what the “canon” of OCS texts is and its relationship to “Church Slavonic” texts produced throughout the Orthodox Slavic world (and on the Dalmatian Coast) well into the eighteenth century. In this sense, the course is preparatory for any further work in premodern East and South Slavic cultures and languages.”[2]

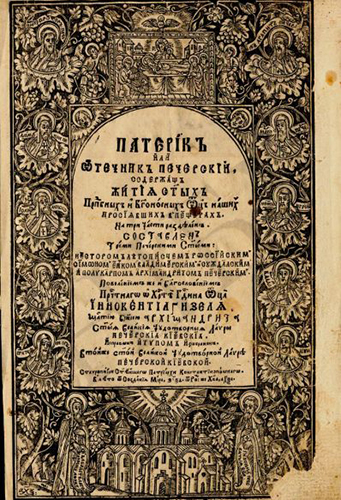

Kievsko-pecherskii paterik is a collection of essays written by different authors from different times. Researchers believe that initially, it consisted of two pieces of the bishop of Suzdal and Vladimir, Simon (1214-1226). One part was a “message” to a monk called Polycarp at the Kyivan cave monastery, and the other part was called the “word” on the establishment of the Assumption Church in Kyiv-Pechersk monastery. Later the book included some other works, such as “The Tale of the monk Crypt” from “Tale of Bygone Years” (1074), “Life” of St. Theodosius Pechersky and dedicated his “Eulogy.” It is in this line-up that “Paterik” represented the earliest manuscript, which was established in 1406 at the initiative of the Bishop of Tver Arsenii. In the 15th century, there were other manuscripts of the “Paterik” like the “Feodosievkaia” and “Kassianovskaia.” From the 17th century on, there were several versions of the printed text.

While there have been several re-editions of this particular book, this Patericon was reprinted in 1991 by Lybid in Kiev. WorldCat indexes ten instances including a 1967 edition that was published in Jordanville by the Holy Trinity Monastery.

Contribution by Liladhar Pendse

Librarian for East European and Central Asian Studies, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Lunt, Horace Gray. Old Church Slavonic Grammar. Berlin; Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, c. 2001, 2010.

- Frick, David. “Courses.” Old Church Slavic: Dept. of Slavic Languages and Literatures, UC Berkeley, slavic.berkeley.edu/courses/old-church-slavic-2. (accessed 1/20/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Paterik Kīevo-Pecherskoĭ : zhitīi︠a︡ svi︠a︡tykh

Title in English: Patericon or Paterikon of Kievan Cave: Lives of the Fathers

Author: Nestor, approximately 1056-1113., Simon, Bishop of Vladimir and Suzdal, 1214-1226., and Polikarp, Archimandrite, active 13th century.

Imprint: 17–? Kiev?

Edition: unknown

Language: Old Church Slavonic

Language Family: Indo-European, Slavic

Source: National Historical Library of Ukraine

URL: bit.ly/paterik

Other online editions:

- http://litopys.org.ua/paterikon/paterikon.htm (accessed 1/20/20)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Paterik Kīevo-Pecherskoĭ : zhitīi︠a︡ svi︠a︡tykh. Kīev : [s.n.], [17–?]. (accessed 1/20/20)

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

In 1919, following World War I and the Paris Peace Conference, the country later called Yugoslavia came into existence in Southeast Europe. However, the country’s name from 1918 to 1929 was the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. After World War II, this country was renamed the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia in 1946. It included the republics of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro, Slovenia, Macedonia, and the autonomous provinces of Vojvodina and Kosovo. The language that was known as Serbo-Croatian was spoken in nearly all of Yugoslavia. In 1991, in the aftermath of the dissolution of Yugoslavia after a period of protracted civil war, all of these constituent parts eventually became independent. First, Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia-Herzegovina became independent in 1991. Serbia and Montenegro were joined, under the name Yugoslavia in 2003 and under the name Serbia-Montenegro in 2006. Thus Serbia as such became a separate country only in 2006 when Montenegro proclaimed independence. Kosovo proclaimed independence in 2008 with the support of the United States and allies. Slovenian and Macedonian were already separate languages. However, outside the formerly united country, the name Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian (BCS) became accepted to denote three different languages that are nearly identical to each other in grammar and pronunciation. However, there are some significant differences in vocabulary. Bosnian and Croatian use a Latin based script while Serbian uses both this alphabet and the Cyrillic alphabet. The term BCS was in fact established at the Hague tribunal (ICTY), and the legitimacy gained in this way allowed its widespread acceptance.

The study of Serbo-Croatian, later BCS, began at UC Berkeley in the aftermath of World War II. Since then the Library’s collections in these languages have been growing steadily and now represent one of the stronger components of Library’s Slavic collections. At UC Berkeley, the situation dramatically changed with the arrival of Professor Ronelle Alexander in 1978. She has been instrumental in helping the Library build up its exemplary Balkan Studies collections for the last four decades. The diversity of her teaching and research expertise ranges from South Slavic languages (Bulgarian, Macedonian, BCS), literatures of former Yugoslavia, Yugoslav cultural history, South Slavic linguistics, Balkan folklore to East Slavic folklore. Although her primary research accomplishments are in South Slavic linguistics, she has also published research on the most widely known and translated Serbian poet, Vasko Popa, and Yugoslavia’s only Nobel prize winner, the prose writer Ivo Andrić.[1]

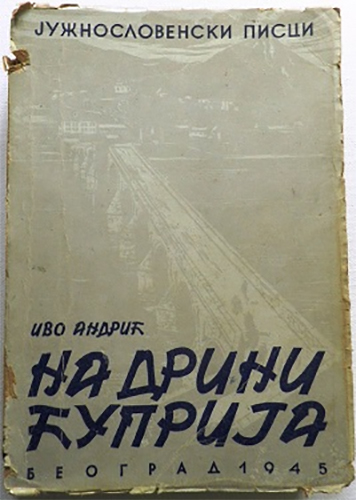

It is challenging to find one single work that would represent the complex nature and relationships between Bosnian, Croatian and Serbian. However, one must note that to this day, the Balkans represent a constantly evolving dynamic mosaic of linguistic diversity that shares a relatively compact geographic topos. For this exhibition, I chose one work that theoretically presents a complicated relationship in Balkans—Ivo Andrić’s prize-winning novel Na Drini ćuprija (“The Bridge on the Drina”) published in 1945.

This historical fiction novel by the Yugoslav writer, Ivo Andrić, revolves around the Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge in Višegrad. This bridge is located in Eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina on the Drina River.[2] It was built by the Ottomans in the mid-16th century, and was damaged several times during the wars of the 20th century but each time rebuilt. It was never entirely destroyed and the “original bridge” remains, and is now on the World Heritage List of UNESCO.[3]

The novel chronicles four centuries of regional history, including the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian occupations. The story highlights the daily lives and inter-communal relationships between Serbs and Bosniaks. Bosnian Muslims-Slavs, now also called Bosniaks. Ever since the end of World War II when three major works of Ivo Andrić (The Bridge on the Drina, Bosnian Chronicle, and The Woman from Sarajevo) appeared in print almost simultaneously in 1945. The Woman from Sarajevo has not stood the test of time, though the other two are major works. A later novel, The Damned Yard, is considered much more important. He has been hailed as a major literary figure by both his country’s reading public and by the critics. His reputation soared even higher when he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1961.[4] The Bridge on Drina has been translated into more than 30 languages.

Contribution by Liladhar Pendse

Librarian for East European and Central Asian Studies, Doe Library

Source consulted:

- Ronelle Alexander authored an article on Andric titled “Narrative Voice and Listener’s Choice in the Prose of Ivo Andrić” in Vucinich, W. S. (1995). Ivo Andric Revisited: The Bridge Still Stands. Research Series, uciaspubs/research/92. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8c21m142 (accessed 7/26/19).

- Ronelle, Alexander. “What Is Naš? Conceptions of “the Other” in the Prose of Ivo Andric.” スラヴ学論集 = Slavia Iaponica = Studies in Slavic Languages and Literatures. 16 (2013): 6-36. (accessed 7/26/19)

- UNESCO World Heritage. “Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge in Višegrad.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre, whc.unesco.org/en/list/1260.

- Moravcevich, Nicholas. “Ivo Andrić and the Quintessence of lpendTime.” The Slavic and East European Journal, vol. 16, no. 3, 1972, pp. 313–318. (accessed 7/26/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Na Drini ćuprija/ На Дрини ћуприја

Title in English: The Bridge on the Drina

Author: Andrić, Ivo, 1892-1975.

Imprint: Sarajevo: Svjetlost, 1946.

Edition: 1st

Language: Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian (BCS)

Language Family: Indo-European, Slavic

Source: Biblioteka Elektronskaknjiga

URL: https://skolasvilajnac.edu.rs/wp-content/uploads/Ivo-Andric-Na-Drini-cuprija.pdf

Other online editions::

- The Bridge on the Drina. Translated from the Serbo-Croat by Lovett F. Edwards. London: George Allen And Unwin Ltd., [c.1945]. Internet Archive

- In Cyrillic: https://www.scribd.com/doc/185963009/Ivo-Andric-Na-Drini-Cuprija-Cirilica

- Audiobook: https://archive.org/details/IvoAndricNaDriniCuprija4Dio

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Na drini ćuprija. Vishegradska khronika. Sarajevo: Svjetlost, 1946.

- The Bridge on the Drina / Ivo Andrić ; translated from the Serbo-Croat by Lovett F. Edwards ; with an introd. by William H. McNeill. Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 1977.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Czech

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

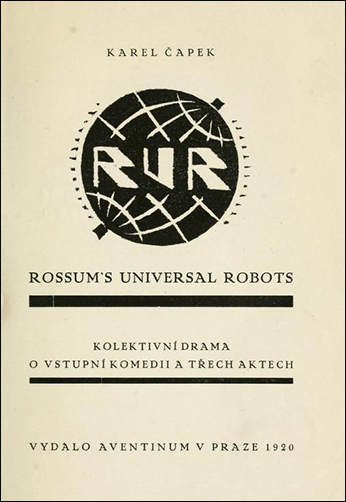

Karel Čapek (9 January 1890 – 25 December 1938) was a Czech writer of the early 20th century. He had multiple roles throughout his career, including playwright, dramatist, essayist, publisher, literary reviewer, photographer and art critic. Nonetheless, he is best known for his science fiction including his novel War with the Newts and the play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), which introduced the word “robot” for the first time in the English language.[1] He also wrote many politically charged works dealing with the social turmoil of his time. Largely influenced by American pragmatic liberalism, he campaigned in favor of free expression and utterly despised the rise of both fascism and communism in Europe.

A funny and surreal story of servitude and technology, R.U.R. was Čapek’s first major work for the stage. The play is a gloriously dystopic science-fiction fantasy about robots and the brave new world of the men who mass-produce them. Robots multiply, are bought and sold and gradually take over every aspect of human existence. As people grow idle and stop procreating, the robots rebel and destroy almost the entire human race. The play was first performed in Prague in 1921.

UC Berkeley professor Ellen Langer describes the novel and the title as follows, “The word robot was derived from the Czech robota, which means “forced labor” — like the French word corvée. The play was an instant hit in Europe and was acclaimed in the United States, perhaps because it captured the terror of those times. World War I had barely ended when the Bolshevik Revolution made Europeans fear an uprising by factory workers. To Čapek, an impassioned democrat, the dictatorship of the proletariat seemed as abhorrent as the recently overthrown Austro-Hungarian autocracy. R.U.R. expressed an idealistic yearning that mass production would free people from want, but realism cautioned that industrialization could also usher in an even more powerful tyranny.

The play seems preachy by current standards, but, as Langer says, “this was an era of polemical plays.” It caused such an intellectual stir in London that Čapek sought to explain its message in an essay published in 1923: “We are in the grip of industrialism; this terrible machinery must not stop, for if it does it would destroy the lives of thousands. It must, on the contrary, go on faster and faster, even though in the process it destroys thousands and thousands of other lives . . . A product of the human brain has at last escaped from the control of human hands. This is the comedy of science.” Thus was born a term that promised either service or subjugation, and, over time, robots migrated from fictional characters to functional creations.[2]

The history of teaching Czech at UC Berkeley is closely tied to the history of the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures. Currently, each year, Dr. Langer offers courses in Basic and Continuing Czech. Besides, the language teaching Professor John Connelly of the Department of History specializes in the Modern East and Central European Political and Social History and History of Catholicism. His groundbreaking research on the history of education came to fruition in his critically acclaimed book Captive University: The Sovietization of East German, Czech, and Polish Higher Education, 1945-1956.

Contribution by Liladhar Pendse

Librarian for East European and Central Asian Studies, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Čapek, Karel, Peter Majer, and Cathy Porter. R.U.R. [London] : Bloomsbury, [2015], 2015. .

- Abate, Tom. “The Robots Among Us.” SFGate, 9 Dec. 2007.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: R.U.R (Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti)

Title in English: R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots)

Author: Čapek, Karel, 1890-1938.

Imprint: V Praze: Vydalo Aventinum, 1920.

Edition: unknown

Language: Czech

Language Family: Indo-European, Slavic

Source: The Internet Archive (University of Toronto)

URL: https://archive.org/stream/rurrossumsuniver00apekuoft#page/n0/mode/2up

Other online editions:

- English translation by David Wyllie.

University of Adelaide, 2015: https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/c/capek/karel/rur - 1922 edition in HathiTrust Digital Library, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/chi.14800394

- Project Gutenberg, http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/13083

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- There are many original Czech editions and English translations in OskiCat.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)