Tag: BL Indo-European Indo-Iranian

Kurdish

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Kurdish is an Indo-European language spoken by approximately 30 million people in the Kurdistan region, and many others in diaspora.[1] Kurdistan spans eastern Turkey, northern Iraq, and western Iran and smaller parts of northern Syria and Armenia.[2] In 1992, Kurds in northern Iraq established the autonomous government, Kurdistan Regional Government, while Kurds in Iran are still seeking official recognition especially in the inhabited Iranian province of Kordestan.[3]

According to Philip Kreyenbroek in the Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2006), “Kurdish is spoken in three main variants: Northern Kurdish, comprising Kurmānjī in the west and dialects spoken from Armenia to Kazakhstan; Central Kurdish, spoken in northeastern Iraq (called Sōrāni) and adjacent areas in Iran (called Kordi or Mokri), as well as in Iranian Kurdistan (called Senne’i); and Southern Kurdish, spoken in Kermanshah province in western Iran (including Lakki and Lori of Posht-e Kuh).”[4] The two widely spoken dialects of Kurdish language are Sōrāni and Kurmānjī; where Sōrāni dialect is written in Perso-Arabic script, the Kurmānjī dialect is written in Latin script.[5]

For most its history, Kurdish was not used as a written language. Those who aspired to contribute to the elevated, written culture of their times wrote in Arabic, Persian or, later, Turkish.[6] Sharāfnama, or The History of Kurdish Nation, a famous book about the history of the Kurds in the medieval period, was written originally in Persian in 1597, and later translated into many languages including Turkish, French, German, Russian, Arabic, Kurdish and English. The first Kurdish translation of Sharāfnama was carried out in Russia in 1858, published in Moscow as a book entitled Tawārīh-i ḳadīm-i Kūrdistān by Mahmud Bayazidi in 1986, in Kurmānjī dialect. A new translation in Sōrāni dialect entitled Sharafnāmah-yi Sharafkhānî Bidlīsī by Hejar was published in Iraq in 1972.[7]

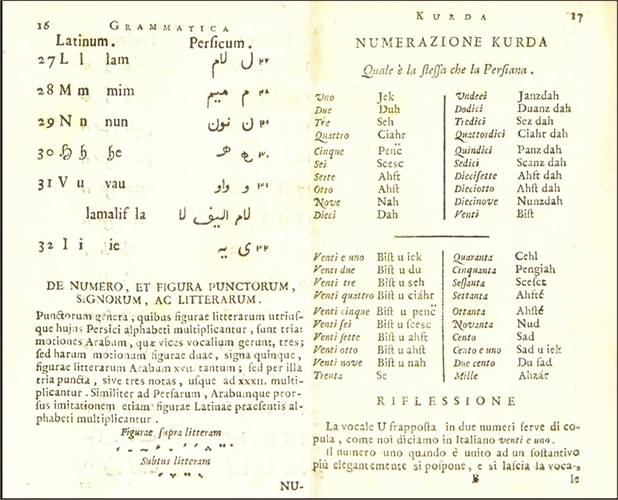

Grammatica e vocabolario della lingua Kurda, which was published in 1787 by Maurizio Garzoni as the first grammar and vocabulary book, was used for a long time among scholars as the standard reference tool for the Kurdish language.[8] More recently in the West, the doctoral thesis of David Neil Mackenzie, which was later published as a book in two volumes entitled Kurdish Dialect Studies is considered a groundbreaking study, especially for Kurdish dialects of Iraq.[9]

Kreyenbroek writes: “Kurdish poetry and prose narratives were transmitted orally. However, the form, language and imagery of the earliest known Kurdish written poetry effortlessly follows the models offered by Arabo-Persian poetry, which suggests that the tradition had been perfected before the known early poets appeared.”[10] One of the examples of popular classical Kurdish poets was Ahmad Khani (1650-1707). He wrote what is considered, the most famous romantic epic Mamu Zayn, which is likened to Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet.” It has been translated and reproduced widely in different languages, works and films.[11]

Recent histories of literary Kurdish literature varies based on different national accounts of the lands of Kurdish speaking people. In 1991 the Turkish government recognized the existence of the Kurdish language, which led to the publication of more literary works in Turkey. In Iraq, the first printing press of Kurdistan was established in Sulaymaniyah in 1919. The printing press helped in establishing various Kurdish newspapers and the production of literary works especially in Sōrāni. In Iran, at least two of the Kurdish poets were recognized nationwide as the “national poet of the Republic of Kurdistan.” These are Abd al-Raḥmān Sharafkandī (Hazhar or Hejar), and Hemin Mokriani. In Armenia, there is a small but active community especially in producing poetry and prose.[12]

At Berkeley, in the Near Eastern Studies Department, with funding support from the Center for the Middle Eastern Studies, Kurdish language and culture classes have been offered sporadically in the last decade. In addition to language classes, Kurdish is included in such courses as the “Sociolinguistics of the Greater Middle East” class, which was offered in 2019 and 2020.[13] In the Library, scholarly works for the study of Kurdish are one of the Library’s distinct strengths for the region.

Contribution by Mohamed Hamed

Middle Eastern & Near Eastern Studies Librarian, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Encyclopædia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Kurdish-language (accessed 8/3/20)

- Encyclopædia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Kurdistan (accessed 8/3/20)

- The Kurdish Project, https://thekurdishproject.org/kurdistan-map (accessed 8/3/20)

- Encyclopedia of Languages & Linguistics / Keith Brown, editor-in-chief; co-ordinating editors, Anne H. Anderson … [et al.]. 2nd ed. (Boston: Elsevier, c2006), 265-266.

- Kurdistan Regional Government, http://cabinet.gov.krd/p/page.aspx?l=12&s=050000&r=305&p=215 (accessed 8/3/20)

- Encyclopædia Iranica, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/kurdish-written-literature (accessed 8/3/20)

- Anwar Soltani, “The Sharafnama of Bitlisi: Manuscript Copies, Translations and Appendixes” in Kurdistanica.com, http://kurdistanica.com/the-sharafnama-of-bitlisi-manuscript-copies-translations-and-appendixes (accessed 8/3/20)

- Encyclopedia of Languages & Linguistics / Keith Brown, editor-in-chief; co-ordinating editors, Anne H. Anderson … [et al.]. 2nd ed. (Boston: Elsevier, c2006), 265-266.

- Encyclopædia Iranica, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/mackenzie-david-neil-1 (accessed 8/3/20)

- Encyclopædia Iranica, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/kurdish-written-literature (accessed 8/3/20)

- Encyclopædia Iranica, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/meme-alan (accessed 8/3/20)

- Encyclopædia Iranica, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/kurdish-written-literature (accessed 8/3/20)

- Kurdish – Berkeley Academic Guide (accessed 8/3/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Grammatica e vocabolario della lingua Kurda

Title in English: Grammar and vocabulary of the Kurdish language

Author: Garzoni, Maurizio, 1730-1790.

Imprint: Rome, 1787.

Edition: 1st

Language: Kurdish

Language Family: Indo-European, Indo-Iranian

Source: The Internet Archive (Wellcome Library)

URL: https://archive.org/details/b28777086/page/n3/mode/2up

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Indo-Persian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Starting with the Ghaznavid dynasty in the 11th century, various Persian-speaking Turkish elites extended their domain over South Asia until the language had its heyday during the mighty Mughal Empire, which during its zenith stretched across almost the entire Indian peninsula. Consequently, Persian not only became the language of the imperial court at Delhi but also of vassal kingdoms across the region, especially when it came to official record-keeping and correspondence. Simultaneously, it became the language of a pan-Indic high culture based on a Sufism tinged with broadminded Hellenistic philosophy that cut across confessional, ethnic, and political boundaries.

During these centuries India produced a number of prominent Persian poets. Many others flocked to the patronage of the sultans and emperors of India, often from Iran, especially after the forced imposition of Shiism by the Safavid sultans. While these immigrants kept the Indian users of Persian connected to the larger literary world of Persian, over time Indo-Persian developed its own distinctive flavor as the language interacted with local cultures and languages. Since the vast majority of Indians who used Persian did not have it as their mother tongue, Persian philology was largely developed in India. The cultural influence of the language was so deep that it continued to be cultivated for nearly a century after the 1830s when the East India Company formally replaced it as the language of administration with English and Hindustani (later called Urdu).

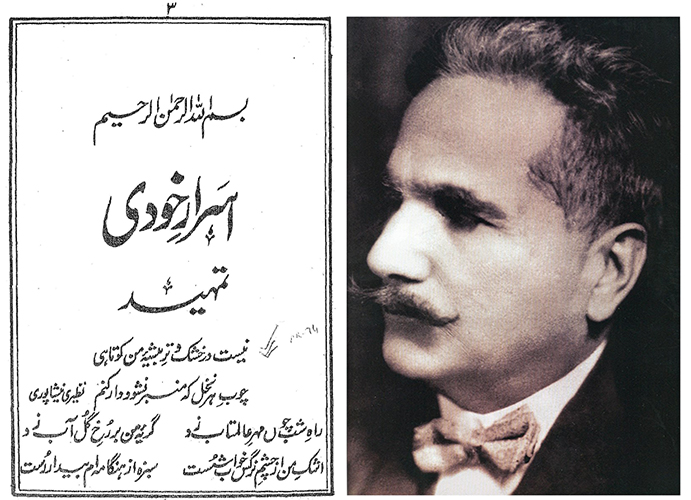

Certain Indo-Persian poets became widely popular throughout the Persian-speaking world. Among these were Amir Khusrow (ca. 1253-132), Abd al-Qadir Bidil (1644-1720), whose verses are still widely appreciated in Afghanistan and Tajikistan, and last but not least, Sir Muḥammad Iqbāl (1877-1938). Born in 1877 in Sialkot, Panjab, Iqbāl studied Persian and Arabic in his hometown before moving to Lahore and studying with Sir Thomas Arnold at Government College. He then went for higher education to the University of Cambridge in the UK and obtained a PhD in philosophy at the Ludwig Maximilian University in Germany. Iqbāl had long been an admirer of the Persian Sufi poet, Jalal al-Din Rumi, and in Europe was deeply influenced by the thought of Nietzsche, Goethe, and Bergson. He was knighted by King George V in 1922. On his return to British India, he began to teach philosophy and English literature at Government College in Lahore where he remained for the rest of his life and lies buried there.

With his deep knowledge of Perso-Islamic philosophy, Sufism, and key European thinkers of his time, Iqbāl set about charting a new course of thought and action for Indian Muslims. A proponent of Pan-Islamism, he was convinced that Muslims had lost sight of the original teachings and aims of their religious culture and had fallen into mystical navel-gazing and empty ritual. In order to reawaken them he resorted to setting out his new revolutionary ideas in the form of Persian (and later, Urdu) poetry.

Asrar-i khudi (Secrets of the Self) was his first book of poetry published in 1915. He preferred writing in Persian as it better expressed his philosophical ideas and also gave him a wider audience. As a mark of his devotion, he used the same poetic meter for his creation that was used by Rumi for his famous Masnavi. He also used the traditional vocabulary of classical Persian poetry but imbued it with new, modern meanings. With its call for resolute action and strongly developed individual personalities that revel in facing challenges, the book acted as a lightning-rod for the younger members of Iqbal’s generation while it courted controversy with older people because of its criticism of the Iranian poet Hafiz whose mystic-philosophical verses were considered the epitome of Sufism. Iqbāl accused him of ensnaring Muslims into the labyrinth of neo-platonic speculation and preaching a negation of the self by declaring it to be an illusion that was best lost by merging into the divine. Iqbāl declared such negation of the self as an affront to God as the self was his greatest gift to human beings and devaluing it sapped their strength to deal with life’s social and moral challenges.

Asrar-i khudi and its call for reappraisal and action became so popular in India and beyond, that the Cambridge orientalist Reynold A. Nicholson translated it into English in 1920. Iqbāl’s ideas were credited with the political awakening of Indian Muslims that culminated in the creation of Pakistan. Decades later, his ideas were to influence some major participants of the Iranian Revolution, in particular Ali Shariati. In many regards Iqbāl’s poetry was to be the swansong of the Indo-Persian literary tradition. While the latter has not died out completely, it does not have the vigor of former centuries. However, its last bright star turned out to be a supernova whose light is still illuminating the Islamic world.

In the Department of South and Southeast Asian Studies, Dr. Gregory Maxwell Bruce—Berkeley’s lecturer for Urdu—also offers courses on Indo-Persian texts.

Contribution by Adnan Malik

Curator and Cataloger for the South Asia Collection

South/Southeast Asia Library

Title: Asraar e Khudi

Title in English: Secrets of the Self

Author: Iqbāl, Sir, Muḥammad, 1877-1938.

Imprint: n.p, [1915].

Language: Indo-Persian

Language Family: Indo-European, Indo-Iranian

Source: The Internet Archive

URL: https://archive.org/details/AsraarEKhudi-AllamaIqbal/page/n1/mode/2up

Other online editions:

- Asrar-i-Khudi. Iqbal Academy Pakistan. (accessed 7/17/20)

- Asrar-i-Khudi. Iqbal Cyber Library. (accessed 7/17/20)

- The Secrets of the Self, English translation of Asrar-i-Khudi by Reynod Nicholson. Iqbal Academy Pakistan. (accessed 7/17/20)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Tarjumān-i Asrār-i khvudī / tafhīmī tarjamah, G̲h̲ulām Dastgīr Shahāb. Pūnah: Ẓafar Iqbāl: Milne ke pate, Salīqah Kitāb Ghar, 1989. Poems in Persian with Urdu translation.

- The Secrets of the Self = Asrar-i khudí: A Philosophical Poem / by Dr. Sir Muhammad Iqbal; translated from the original Persian, with introd. and notes by Reynold A. Nicholson. Lahore: Muhammad Ashraf 1964.

- The Secrets of the Self: English Rendering of Iqbal’s Asrar-i khudi / by Maqbool Elahi. Lahore: Iqbal Academy Pakistan, 1986.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Judeo-Persian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Jews have lived among Persian speakers, and spoken Persian dialects, since at least the period of the Achaemenid Empire (550 BC–330 BCE). Influences from Iranian linguistic and literary traditions are evident in post-exilic books of the Hebrew Bible and apocrypha, in addition to Second Temple and classical rabbinic traditions. The rise of Persian literature written by Jews in Hebrew script coincided with the New Persian literary renaissance that began in the eighth century CE. Today, Jewish communities with roots in Iran, Central Asia, the Caucasus, and elsewhere continue to write and speak in dialects of Persian, but these have yet to receive a degree of popular or scholarly consideration commensurate with their status as historically-significant and enduring Jewish languages.

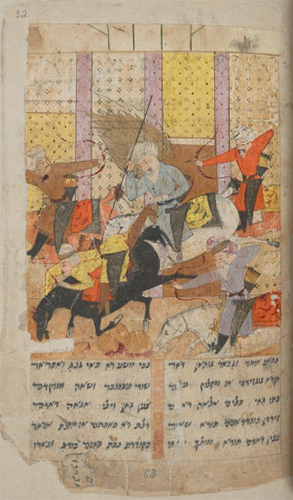

The Fath-Nāmeh or “Book of Conquests” is a versified rendition of stories from the books of Joshua, Judges, Ruth, I Samuel, and II Samuel in Judeo-Persian (New Persian written with Hebrew characters) by the poet ‘Imrāni. ‘Imrāni lived in Isfahan and Kashan during the late Timurid and early Safavid periods (15th/16th century CE) and composed in the masnavī poetic style—in rhyming couplets following a meter of eleven syllables—comparable in form to the Masnavi-e Ma’navi (“Spiritual Couplets”) of the 13th-century poet Rumi. Like similar works by his predecessor, Mowlānā Shāhin-i Shirāzi, and his successors, Aḥaron ben Mashiaḥ and Khwājaj Bukhārā’ī, the Fatḥ-Nāmah is an example of Jewish ‘rewritten bible’ in the Iranian epic mode exemplified by the Shāh-Nāmeh (“Book of Kings”) of Ferdowsi (10th/11th century). Rhetorical, symbolic, and thematic elements also recall the Leili o Majnun (“Layla and Majnun”) of Nizami Ganjavi (12th/13th century) and the poetry of Hafez (14th century).

While he employs recognizably Islamic terminology such as tahlīl (“praise” of God, usually referring to the first portion of the Muslim shahādah formula) and tawḥīd (“oneness” of God), ‘Imrāni’s frequent inclusion of Hebrew words—sometimes with Persian endings e.g. kohen-ān—points to his Jewish background, as do his choices of source material. Other works by ‘Imrāni include (1) the Sufi-influenced Ganj-Nāmeh (“Book of Treasure”), a versified rendering of the first four chapters of the Mishnaic tractate Avot; (2) the Ḥanukkah-Nāmeh or Ẓafar-Nāmeh (“Book of Victory”), which relates the Maccabean narrative; (3) midrashic retellings of the ten Jewish sages martyred during the reign of Hadrian, of the seven sons of Hannah martyred during the Hasmonean revolt, and of the sacrifice of Isaac; (4) a treatise based on Maimonides’ Thirteen Principles; and (5) poetic works on themes of moral, religious, and practical instruction.

The Fath-Nāmeh also refers to stock themes and characters from the Iranian epic tradition—such as the equation of the reign of the biblical king Saul to that of the Pishdadian ruler Jamshid and the use of symbolic imagery from Ferdowsi’s Shāh-Nāmeh. Passages that relate didactic advice reflect the Pahlavi andarz (“instruction”) traditions associated with Ādurbād ī Mahrspandān and other Sasanian-era Zoroastrian figures. Accompanying illustrations, as Orit Carmeli observes, reflect styles known from other Persian manuscripts of the Safavid and early Qajar periods. Vera Basch Moreen’s English translation constitutes a significant advance in rendering such material for non-specialists, spotlighting the richness of the Judeo-Persian tradition within the broader oeuvre of Jewish literature.

Delve into Judeo-Persian:

- Read about Judeo-Persian at the Jewish Languages Project and in Encyclopedia Iranica

- Browse UCB books in and about Judeo-Persian

- Study Persian and Hebrew in the UCB Department of Near Eastern Studies

Contribution by Alexander Warren Marcus

PhD Student, Department of Religious Studies, Stanford University

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Fath Nāma

Title in English: The Book of Conquests

Author: Emrānī, 1454-1536

Imprint: 1675-1724

Edition: Original manuscript

Language: Judeo-Persian

Language Family: Indo-European, Indo-Iranian

Source: The British Library

URL: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Or_13704

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- The Bible as a Judeo-Persian Epic : an Illustrated Manuscript of ‘Imr̄anī’s Fatḥ-Nāma = Miḳra ke-epos Parsi-Yehudi : ketav yad meʼuyar shel ha-Fatḥ-Namah le-ʻImrani / Vera Basch Moreen with Orit Carmeli. Jerusalem : Ben Zvi Institute for the Study of Jewish Communities in the East, 2016.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Hindi

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

The two great Indian epics, the Mahābhārata and the Ramayana, dominate South Asian cultures in ways that few other literary productions do. Both epics have to do with the heroic exploits of the human incarnation of the Hindu deity Vishnu, one of the most widely worshipped gods of the Hindu pantheon. The Ramayana deals with the story of King Ramachandra, the seventh incarnation of Vishnu, who came down to Earth to establish just rule and a harmonious society.

King Rama is not only the ideal monarch and warrior but also embodies the virtues of justice, wisdom, patience, and perseverance. He is an obedient son, a generous brother, and a caring husband. His rule became synonymous with justice and good governance so that throughout the centuries the expression rama rajya (Rama’s rule) has been used to describe the ideal government.

The most famous version of the Ramayana is the Sanskrit composition of Valmiki known as Valmiki’s Ramayana. It has the status of a sacred text and is highly revered. It is also a masterpiece of Sanskrit literature. There were many versions of the Ramayana composed subsequently, both in Sanskrit and other languages. Some became more popular than others, but one is justified to say that after Valmiki’s Ramayana, the version that is most famous is the Ramacaritamanasa created in the Awadhi dialect of Hindi by Tulasidasa in the 16th century. In fact, Tulasidasa’s Ramayana quickly garnered wide popularity and its recitation became part of the worship service of many sects and religious traditions of Vaishnava Hinduism, especially after the introduction of the printing press in the early 19th century. Its communal recital, often set to a distinctive tune, continues to this day. Tulasidasa was himself an ardent devotee of Lord Rama and in expressing his love and reverence for the divine incarnation in beautiful poetry he managed to create one of the greatest poetic works of Hindi literature.

Tulasidasa was born in the region of Avadh in what is now eastern Uttar Pradesh in modern India. There is disagreement about his date of birth, but scholars generally consider it to be around 1532 CE. Traditional accounts state that he was a Brahmin by caste and was initiated into a mystic and ascetic lineage devoted to the loving worship of God through the incarnation of Rama. He is supposed to have spent time as a student with various sages and teachers in Banaras where he learnt the classical Sanskrit texts as well as Vaishnava scriptures. He decided to compose a Ramayana in Awadhi for the edification of the general population, and thus, composed the Ramacaritamanasa, The Lake of the Deeds of Rama. He composed a number of other works as well but the Ramacaritamanasa remained his magnum opus. He died in 1623 in Banaras.

When he set about composing the Ramacaritamanasa, Tulasidasa had a long tradition of composing Ramayanas to look up to going all the way back to Valmiki. At the same time, he was well aware of the literary styles and compositions of his own time when the beginnings of Hindi literature had already been made and a corpus and canon were slowly but steadily evolving. Tulasidasa was to leave his mark on this evolution.

Tulasidasa followed the conventions of chanda prosody that had been the hallmark of Sanskrit poetry and was also followed in other languages, especially for works in Aparbhramsa, the medium of literary production before the rise of Hindi. He also might have been inspired by the metrical structure of the premakhya, a genre of love ballads popular in his days, in creating the basic form for the Ramacaritamanasa. The work is composed in regular arrangements of caupais (quatrains) and dohas (couplets) and he used a different meter for every section of the work.

Tulasidasa used his considerable literary skills to retell the story of the struggles and ordeals of Lord Rama, his brother Lakshmana, his wife Sita, and his devoted disciple, the monkey god, Hanumana, as they faced family feuds, exile, and an epic war against the demon king, Ravana, who had kidnapped Sita, until they returned victorious and vindicated to their capital, Ayodhya, to establish a just and prosperous kingdom.

Ramacaritamanasa is not just a skilled literary retelling of the ancient epic in the charming Awadhi dialect but is redolent with Tulasidasa’s own loving devotion to Lord Rama which seeps through its every line. Perhaps that is why millions of devotees of Lord Rama continue to use it to express their own love and devotion in prayer.

Hindi has been taught UC Berkeley since the late 1960s. Currently, there are two Hindi lecturers. Usha Jain has authored books on Hindi language instruction, including Introductin to Hindi Grammar (1995), Intermediate Hindi Reader (1999), and, Advanced Hindi Grammar (2007). The other instructor is Dr. Nora Melnikova whose interests include second language teaching, modern Theravada Buddhism, and the Early Modern languages and literature of North India. She has also translated Mirabai’s medieval Hindi poems and Erich Frauwallner’s History of Indian Philosophy into Czech.

Contribution by Adnan Malik

Curator and Cataloger for the South Asia Collection

South/Southeast Asia Library

Title: Rāmacaritamānasa

Title in English: The Rámáyana of Tulsi Dás

Authors: Tulasīdāsa, 1532-1623.

Imprint: Allahabad : North-western Provinces Government Press, 1877.

Edition: Indo-European, Indo-Aryan

Language: Hindi

Language Family: Indo-European, Indo-Iranian

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (UC Berkeley)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006125797

Other online editions:

- Recitation of text on YouTube (accessed 11/19/19)

- The Rámáyana of Tulsi Dás. Rev. and illustrated. Allahabad : North-western Provinces Government Press, 1883. (Internet Archive)

- The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki : An Epic of Ancient India / introduction and English translation by Robert P. Goldman ; annotation by Robert Goldman and Sally J. Sutherland. Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, ©1984- ©2017. (Project Muse – UCB only)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- The Rámáyana of Tulsi Dás. Allahabad : North-western Provinces Government Press, 1877.

- The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki : An Epic of Ancient India / introduction and English translation by Robert P. Goldman ; annotation by Robert Goldman and Sally J. Sutherland. Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, ©1984- ©2017.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Urdu

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

The dastan is a genre of oral and prose narrative that initially developed in Persian but then spread to other languages influenced by the Persian literary tradition. To be sure, oral tale-telling is hardly unique to Persian or Persian-influenced languages, but the dastan has some unique literary features that make it stand out. Dastans often have very long story lines that can be embellished and stretched even further through detailed descriptions of characters, events, and locations. With their dramatic narratives, dastans are primarily meant for oral performances and enjoying the richness of language and literary traditions.

One of the most popular dastans in South Asia was Dastan-i Amir Hamzah (the Dastan of Amir Hamzah). It had its origins in 11th century Iran, but eventually made its way to India where it developed many versions in Persian. Dastan-i Amir Hamzah was popular at the Mughal court where Emperor Akbar was an avid fan.

The hero of the dastan is Hamzah, an uncle of the Prophet Muhammad, who is depicted as a great warrior and supporter of his nephew in early Islamic sources. The adventures of the Hamzah of the dastan, however, are based on fantasy. In the dastan, Amir Hamzah is begged by the wise vizier of Naushirvan, the king of Persia, to help the latter fight his enemies. The gallant Hamzah agrees and fights many battles. He also falls in love with Naushirvan’s daughter, Mahnigar, and seeks her hand in marriage, which requires him to fight more battles and vanquish more enemies. He is accompanied in his travails by his trusted companions, the laconic and serious Muqbil, skilled in archery, and the dishonest but loyal ‘Amr the ‘Ayyar. ‘Ayyars were skilled in espionage and disguises and were notorious for their trickery and special equipment (much like the ninjas). ‘Amr is not only an exceptionally talented ‘ayyar but is extremely greedy even by the low standards of his profession.

As luck would have it, before he could wed Mahnigar, Amir Hamzah is wounded in a battle and is rescued by Shahpal, the king of paris (fairies) who requests that Hamzah help him regain his kingdom in the magical world of Qaf that had been overtaken by demons. Consequently, Amir Hamzah spends eighteen years in the supernatural world of Qaf fighting sorcerers and demons, who can cast such potent spells they can create entire worlds of illusion called tilism. Amir Hamzah and his companions can never be sure whether they are operating in a tilism or in the world of Qaf (which itself is magical) and had to resort to all sorts of ways to break the spells, often with help from saintly figures. Incidentally, an alternative title for the dastan, especially its version based on selections from earlier ones is, Tilism-i Hosh Ruba, The Sense-stealing Tilism.

After eighteen years of adventures, Amir Hamza is finally able to pay his debt to Shahpal. He returns to marry Mahnigar. They have a son named Qubad, but Amir Hamza’s adventures do not end there. He is compelled to fight other enemies and demons until he is called back to Arabia by his nephew, the Prophet Muhammad, to help him fight the enemies of Islam.

When, starting in the 16th century, Urdu became a medium of literary production, dastans began to be composed in it as well. This included versions of Dastan-i Amir Hamzah that were popular enough to have professional story-tellers, called dastan-go or qissah-khvan. Owing to its popularity and the richness of its language, John Gilchrist, head of the Hindustani Department at Fort William College, Calcutta, commissioned a teacher at the department, Khalil Ali Khan Ashk who was also a dastan-go, to publish a printed version of the dastan. Ashk produced the first printed edition of Dastan-i Amir Hamzah in 1801. This makes it not only the earliest printed edition of the dastan but also one of the earliest printed books in Urdu. Ashk’s version consisted of about 500 pages spread over four volumes. It was published many times in the subsequent decades in Delhi, Lucknow, and Bombay. Many of these editions were published by the famous Munshi Nawal Kishore of Lucknow, who published another version by Abdullah Bilgrami in 1871. By the 1920s, the rise of the novel and changing tastes eclipsed the fortunes of dastans and they fell out of favor.

The edition included here is the 1863 edition of Askh’s version that was published from Bombay.

Urdu has been part of language instruction at UC Berkeley since the late 1950s. UC Berkeley also runs the Berkeley Urdu Language Program in Pakistan (BULPIP) in collaboration with the American Institute of Pakistan Studies. In addition, the Institute for South Asia Studies launched the Berkeley Urdu Initiative in 2011 to further promote the study of Urdu at Cal. The leading light for many of the Urdu-related events and activities is Dr. Gregory Maxwell Bruce, the Urdu language instructor, who joined the Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies in the Fall of 2016.

Contribution by Adnan Malik

Curator and Cataloger for the South Asia Collection

South/Southeast Asia Library

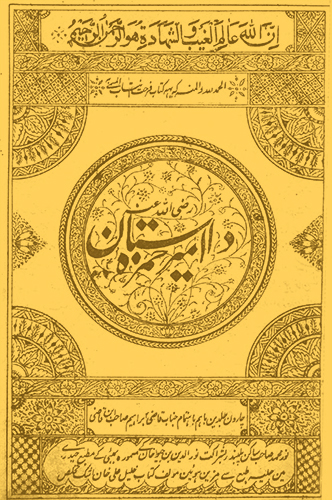

Title: Dāstān-i Amīr Ḥamzah razī Allāh ʻanh

Authors: unknown

Imprint: Bambaʼī : Maṭbaʻ Ḥaydarī, 1280 [1863].

Edition: n/a

Language: Urdu

Language Family:

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (UC Berkeley)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100188630

Other online editions:

- The Romance Tradition in Urdu : Adventures from the Dastan of Amir Hamzah / translated, edited, and with an introduction by Frances W. Pritchett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991. Introductory material from the printed edition (modified and corrected wherever appropriate) and the longer translation of the Bilgrami edition.

- Text of Bigrami/Naval Kishore edition (Rekhta: The Largest Website of Urdu Poetry)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Dāstān-i Amīr Ḥamzah razī Allāh ʻanh. Bambaʼī : Maṭbaʻ Ḥaydarī, 1280 [1863].

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)