The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

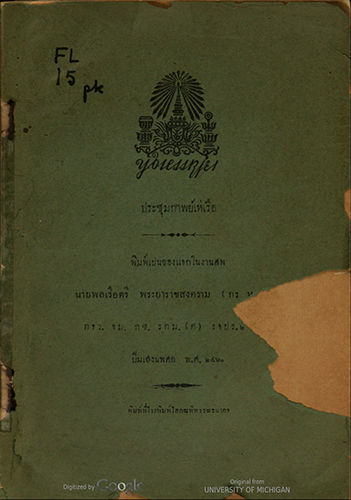

Thai

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

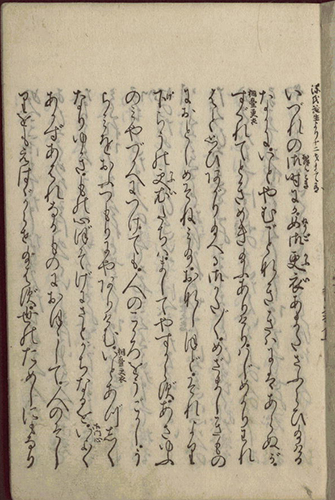

From the beginning of its known history, Thai was the official language of the monarchy of Thailand. Spoken by more than 60 million people today, it retains a formal vocabulary of respect, used in ritual and in addressing the royal family. Its writing system is a careful adaptation of that of Khmer to a language with a distinct sound pattern and flavor.[1]

Prachum kāp hē r̄ưa is a collection of Kāp hē r̄ưa. Kāp hē r̄ưa is a traditional genre of Thai literature written and used for royal barge processions in Thailand. The content of Kāp hē r̄ưa is usually a description of a variety of royal barges and natural scenery that the poet sees along the way, especially trees, fish, and birds. Some poets also write about their lovers from whom they have to part upon their journey.

The Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies (SSEAS) at UC Berkeley offers programs in both undergraduate and graduate instruction and research in the languages and civilizations of South and Southeast Asia from the most ancient period to the present. Instruction includes intensive training in several of the major languages of the area including Bengali, Burmese, Hindi, Khmer, Indonesian (Malay), Pali, Prakrit, Punjabi, Sanskrit (including Buddhist Sanskrit), Filipino (Tagalog), Tamil, Telugu, Thai, Tibetan, Urdu, and Vietnamese, and specialized training in the areas of literature, philosophy and religion, and general cross-disciplinary studies of the civilizations of South and Southeast Asia.[2] Outside of SSEAS where beginning through advanced level courses are offered in Thai, related courses are taught and dissertations produced across campus in Anthropology, Asian American Studies, Comparative Literature, Ethnic Studies, Folklore, History, Linguistics and Political Science (re)examining the rich history and culture of Thailand.[3]

Arthit Jiamrattanyoo

PhD Student, Department of History, University of Washington

Sources consulted:

- Dalby, Andrew. Dictionary of Languages: The Definitive Reference to More Than 400 Languages. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998.

- Department of South & Southeast Asian Studies, UC Berkeley (accessed 2/21/20)

- Thai (THAI) – Berkeley Academic Guide (accessed 2/21/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Prachum kāp hē r̄ưa

Title in English: n/a

Author: Gedney, William J., Damrongrāchānuphāp Prince, son of Mongkut, King of Siam 1862-1943.

Imprint: [Phranakhō̜n?]: Rōngphom Sōphon Phiphatthanākō̜n, 2460 [1917].

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Thai

Language Family: Kra-Dai

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Michigan)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000415896

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Polish

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

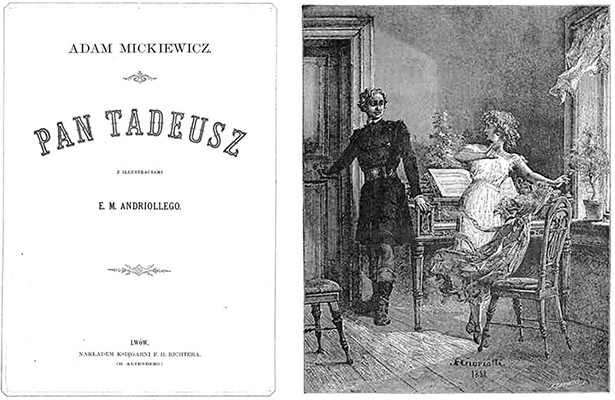

Modern day academics and literary scholars have spent considerable time studying the phenomenon related to the use of literature to create national heroes. While, the use of literary forms gives a particular author the means to incorporate the cultural sensitivities, the literary forms that evolve are functions of the society and time in which a particular author was born. Pan Tadeusz as an epic poem is not an exception but reinforces the stereotypes of a particular period through the poetics of Adam Mickiewicz.

Adam Mickiewicz was born in Nowogródek of the Grand Dutchy of Lithuania in 1798. Nowogródek is today known as Novogrudok and is located in Republic of Belarus. He was educated in Vilnius, the capital of today’s Lithuania. He is recognized as the national literary hero of Poland and Lithuania. However, most of his adulthood was spent in exile after 1829. In Russia, he traveled extensively and was a part of St. Peterburg’s literary circles.[1] There have been several works that track the trajectory of Mickiewicz’s travel and exile. Pan Tadeusz reflects the realities of the partition of the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth from the perspective of the poet. The drive for liberty and freedom were indeed two traits of Adam Mickiewicz’s life journey that cannot be ignored. The synopsis of the story has been summarized below. Also of interest are the illustrations to accompany the storyline. One prominent illustrator was his compatriot Michał Elwiro Andriolli (1836-1893).[2]

Pan Tadeusz is the last major work written by Adam Mickiewicz, and the most known and perhaps most significant piece by Poland’s great Romantic poet, writer, philosopher and visionary. The epic poem’s full title in English is Sir Thaddeus, or the Last Lithuanian Foray: a Nobleman’s Tale from the Years of 1811 and 1812 in Twelve Books of Verse (Pan Tadeusz, czyli ostatni zajazd na Litwie. Historia szlachecka z roku 1811 i 1812 we dwunastu księgach wierszem). Published in Paris in June 1834, Pan Tadeusz is widely considered the last great epic poem in European literature.

Drawing on traditions of the epic poem, historical novel, poetic novel and descriptive poem, Mickiewicz created a national epic that is singular in world literature.[3] Using means ranging from lyricism to pathos, irony and realism, the author re-created the world of Lithuanian gentry on the eve of the arrival of Napoleonic armies. The colorful Sarmatians depicted in the epic, often in conflict and conspiring against each other, are united by patriotic bonds reborn in shared hope for Poland’s future and the rapid restitution of its independence after decades of occupation.

One of the main characters is the mysterious Friar Robak, a Napoleonic emissary with a past, as it turns out, as a hotheaded nobleman. In his monk’s guise, Friar Robak seeks to make amends for sins committed as a youth by serving his nation. The end of Pan Tadeusz is joyous and hopeful, an optimism that Mickiewicz knew was not confirmed by historical events but which he designed in order to “uplift hearts” in expectation of a brighter future.

The story takes place over five days in 1811 and one day in 1812. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had already been divided among Russia, Prussia and Austria after three traumatic partitions between 1772 and 1795, which had erased Poland from the political map of Europe. A satellite within the Prussian partition, the Duchy of Warsaw, had been established by Napoleon in 1807, before the story of Pan Tadeusz begins. It would remain in existence until the Congress of Vienna in 1815, organized between Napoleon’s failed invasion of Russia and his defeat at Waterloo.

The epic takes place within the Russian partition, in the village of Soplicowo and the country estate of the Soplica clan. Pan Tadeusz recounts the story of two feuding noble families and the love between the title character, Tadeusz Soplica, and Zosia, a member of the other family. A subplot involves a spontaneous revolt of local inhabitants against the Russian garrison. Mickiewicz published his poem as an exile in Paris, free of Russian censorship, and writes openly about the occupation.

The poem begins with the words “O Lithuania”, indicating for contemporary readers that the Polish national epic was written before 19th century concepts of nationality had been geopoliticized. Lithuania, as used by Mickiewicz, refers to the geographical region that was his home, which had a broader extent than today’s Lithuania while referring to historical Lithuania. Mickiewicz was raised in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the multicultural state encompassing most of what are now Poland, Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine. Thus Lithuanians regard the author as of Lithuanian origin, and Belarusians claim Mickiewicz as he was born in what is Belarus today, while his work, including Pan Tadeusz, was written in Polish.”

Polish is a prominent member of the West Slavic language group. It is spoken primarily in Poland and serves as the native language of the Poles who live in various parts of world including the United States. Poles have been involved in the history of the American Revolution from early on. One such example is that of Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko who was an engineer and fought on the side of American revolution.

At UC Berkeley, Polish language teaching has been a major part of the portfolio of the Slavic languages that are being taught at the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures. This department was home to UC Berkeley’s only faculty member, Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz (1911-2004), to have ever received the prestigious Nobel Prize in Literature.[4] The tradition of Milosz is continued today in the same department by Professor David Frick. Professor John Connelly in the History department is another luminary scholar of Polish history.

Marie Felde, who reported on his death in the UC Berkeley News Press release on 14th August 2004 noted, “When Milosz received the Nobel Prize, he had been teaching in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literature at Berkeley for 20 years. Although he had retired as a professor in 1978, at the age of 67, he continued to teach and on the day of the Nobel announcement he cut short the celebration to attend to his undergraduate course on Dostoevsky.”[5]

Contribution by Liladhar Pendse

Librarian for East European and Central Asian Studies, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Adam Mickiewicz, 1798-1855; In Commemoration of the Centenary of His Death in UNESDOC DIGITAL LIBRARY (accessed 2/21/20)

- Andriolli : Ilustracje do “Pana Tadeusza” (accessed 2/21/20)

- “Pan Tadeusz – Adam Mickiewicz,” Culture.pl (accessed 2/21/20)

- The Nobel Prize in Literature 1980, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1980/summary (accessed 2/21/20)

- UC Berkeley News (August 14, 2004), https://www.berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/2004/08/15_milosz.shtml (accessed 2/21/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Pan Tadeusz

Title in English: Pan Tadeusz or The Last Foray in Lithuania

Author: Mickiewicz, Adam, 1798-1855.

Imprint: Lwów : Nakładem Księgarni F.H. Richtera (H. Altenberg) , [1882?].

Edition: unknown

Language: Polish

Language Family: Indo-European, Slavic

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)

URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112046983406

Other online editions:

- Pan Tadeusz; czyli, Ostatni zajazd na Litwie. Historja szlachecka z r. 1811 i 1812, we dwunastu ksiegach, wierszem, przez Adama Mickiewicza … Wydanie Alexandra Jelowickiego; s popiersiem autora. 1st edtion. Paryz, 1834. (Gallica – Bibliothèque nationale de France)

- Pan Tadeusz; czyli, Ostatni zajazd na Litwie. Historja szlachecka z r. 1811 i 1812, we dwunastu ksiegach, wierszem, przez Adama Mickiewicza … Wydanie Alexandra Jelowickiego; s popiersiem autora. 1st edtion. Paryz, 1834. (Project Gutenberg)

- Pan Tadeusz czyli ostatni zajazd na Latwie. Warszawa : Fundacja Nowoczesna Polska, 2016.

- Pan Tadeusz or The Last Foray in Lithuania: A Story of Life Among Polish Gentlefolk in the Years 1811 and 1812 in Twelve Books. Translated into English by George Rapall Noyes. London : Dent ; New York : Dutton, 1917. (Project Gutenberg )

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Pan Tadeusz; czyli, Ostatni zajazd na Litwie. Historja szlachecka z r. 1811 i 1812, we dwunastu ksiegach, wierszem, przez Adama Mickiewicza … Wydanie Alexandra Jelowickiego; s popiersiem autora. 1st edition. Paryz, 1834.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Yoruba

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Yoruba, a tonal language, is spoken by nearly 40 million of the 185 million people living in Nigeria (2016 World Bank estimates). Some two hundred thousand Yoruba speakers also live in neighboring Benin and Togo. In Nigeria, Yoruba claims the second most speakers nationwide behind only English, the former language of colonial British Nigeria. In turn, Yoruba along with the two other national indigenous languages (Ibo and Hausa) are hegemonizing smaller, local languages throughout the country. Yoruba is part of the Yoruboid branch of the Niger-Congo language family, of which there are some 1,500 other languages. It includes numerous loanwords from English and as a result of the slave trade was important in Brazil, Cuba and other American countries.

Published in Lagos, Nigeria in 1885, Iwe Alọ is a collection of nearly 200 riddles and puzzles written in Yoruba. The author, Nigerian born David Brown Vincent, changed his name to Mojola Agbebi and preferred African to European fashion, due largely to his anti-colonial sentiment. After his ordination as a Baptist minister in Liberia in 1894, he summed-up his feelings: “I believe every African bearing a foreign name to be like a ship sailing under foreign colours and every African wearing a foreign dress is like the jackdaw in peacock feathers.” The print edition of Iwe Alọ, housed in the Bancroft Library, is part of the renowned Yoruba collection of William and Berta Bascom, which comprises some 470 volumes with plenty of examples of similarly early Yoruba language publications. The digitized edition of the Iwe Alọ is freely available through the HathiTrust Digital Library.

Contribution by Adam Clemons

Librarian for African and African American Studies, Doe Library

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Iwe Alọ

Title in English: [Booklet]

Author: Agbebi, Mojola, 1860-1917. (David Brown Vincent)

Imprint: Lagos: General Printing Press, 1885.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: Yoruba

Language Family: Niger-Congo

Source: HathiTrust Digial Library (UCLA)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/101690224

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Iwe Alọ. Foreward by D.B. Vincent. Lagos: General Printing Press, 1885.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Classical Japanese

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Ōzora o kayou maboroshi yume ni dani, miekonu tama no yukue tazune yo

大空をかよふ幻夢にだに 見えこぬ魂の行方たづねよ

O seer who roams the vastness of the heavens, go and find for me a soul

I now seek in vain even when I chance to dream. (trans. Royall Tyler)

Genji monogatari, or the Tale of Genji, is generally considered as the supreme masterpiece of Japanese prose literature. Written in the early 11th century by a court lady Murasaki Shikibu, it is often called the world’s earliest novel. Although a holograph manuscript is not extant, it is known that this literary work, approximately the length of the present Genji of over 50 chapters, had been completed by 1008 and widely circulated by 1021. The work recounts the life of Hikaru Genji, or “Shining Genji,” the son of an ancient Japanese emperor Kiritsubo and a low-ranking but beloved concubine Lady Kiritsubo, with a particular focus on Genji’s romantic life with various women and the customs of the aristocratic society of the time. The Tale of Genji has been extremely influential on later literature and other art forms, including painting, Nō drama, kabuki theater, cinema, television, and even manga.

Helen McCullough (1918-1998) who studied and taught Japanese literature at UC Berkeley for many years explained, “the Tale of Genji transcends both its genre and age. Its basic subject matter and setting—love at the Heian court—are those of the romance, and its cultural assumptions are those of the mid-Heian period, but Murasaki Shikibu’s unique genius has made the work for many a powerful statement of human relationships, the impossibility of permanent happiness in love, the ineluctability of karmic retribution, and the vital importance, in a world of sorrows, of sensitivity to the feelings of others.”[1] Indeed this literary text has been studied by scholars for many centuries. In the Edo period (1603-1868), various printed editions of the Tale of Genji as well as numerous annotations and criticisms came to be published. It is said that 150 to 200 research articles and books on the Tale of Genji are published in Japan every year.[2] The Tale of Genji has been translated in many languages, including six major translations into English.

In 1900 Japanese instruction as foreign language began at UC Berkeley as the first institution to offer such academic program in the U. S.[3] Today the Department of East Asian Languages & Cultures offers the first through fifth year level courses and a specialized course for heritage students. Japanese is the national language of Japan with population of 126 million people. According to the Survey on Japanese-Language Education Abroad conducted by the Japan Foundation,more than 3.9 million people were studying Japanese language at 16,000 institutions worldwide in 2012.[4]

Contribution by Toshie Marra

Librarian for Japanese Collection, C. V. Starr East Asian Library

Sources consulted:

- McCullough, Helen Craig, comp. Classical Japanese Prose: An Anthology. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1990, 9.

- Akiyama, Ken. “Genji monogatari.” In Nihon daihyakka zensho, via JapanKnowledge https://japanknowledge.com/lib/display/?lid=1001000081597 (accessed 2/7/20)

- Hasegawa, Yoko. “Nihongo kyōiku no kongo: Beikoku no shiten kara.” In Henkasuru kokusai shakai ni okeru kadai to kanōsei, by Dai 10-kai Kokusai Nihongo Kyōiku Nihon Kenkyū Shinpojūmu Taikai Ronbunshū Henshū Iinkai. Hong Kong: Society of Japanese Language Education Hong Kong, 2016, 1.

- Japan Foundation. Survey on Japanese-Language Education Abroad 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20160918101514/http://www.jflalc.org/school-survey-2012.html (accessed 2/7/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Genji monogatari 源氏物語

Title in English: Tale of Genji

Author: Murasaki Shikibu, b. 978?

Imprint: Kyōto: Yao Kanbē, 1654

Language: Classical Japanese

Language Family: Japonic

Source: The Library of Congress

URL: https://www.loc.gov/rr/asian/tale-of-genji.html

Other online editions:

- Kaigai Genji jōhō 海外源氏情報 = Genji Overseas (in Japanese only), provided by Prof. Tetsuya Ito: http://genjiito.org/update/genjigenpon_database/

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Murasaki Shikibu, b. 978?-. Genji monogatari. Kyōto: Yao Kanbē, 1654.

East Asian Rare 5924.6.2551

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Portuguese

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Ó mar salgado, quanto do teu sal

São lágrimas de Portugal!

Quando virás, ó Encoberto,

Sonho das eras portuguez,

Tornar-me mais que o sopro incerto

De um grande anceio que Deus fez?

O salty sea, so much of whose salt

Is Portugal’s tears!

When will you come home, O Hidden One,

Portuguese dream of every age,

To make me more than faint breath

Of an ardent, God-created yearning?

(Trans. Richard Zenith, Message)

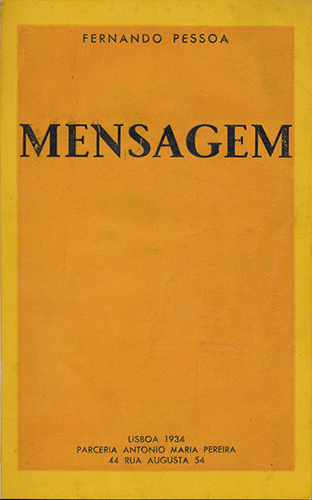

Living in a paradoxical era of artistic experimentalism and political authoritarianism, Fernando António Nogueira Pêssoa (1888-1935) is considered Portugal’s most important modern writer. Born in Lisbon, he was a poet, writer, literary critic, translator, publisher and philosopher. Most of his creative output appeared in journals. He published just one book in his lifetime in his native language Mensagem (“Message”). In the same year this collection of 44 poems was published, António Salazar was consolidating his Estado Novo (“New State”) regime, which would subjugate the nation and its colonies in Africa for more than 40 years. Encouraged to submit Mensagem by António Ferro, a colleague with whom he previously collaborated in the literary journal Orpheu (1915), Pessoa was awarded the poetry prize sponsored by the National Office of Propaganda for the work’s “lofty sense of nationalist exhaltation.”[1]

Because of its association with the Salazar’s dictatorship, Mensagem was regarded as a national monument but also as something reprehensible. Translator Richard Zenith describes it as a “lyrical expansion on The Lusiads, Camões’ great epic celebration of the Portuguese discoveries epitomized by Vasco de Gama’s inaugural voyage to India.”[2] At the same time, it traces an intimate connection to the world at large, or rather, to various worlds (historical, psychological, imaginary, spriritual) beginning with the circumscribed existence of Pessoa as a child. Longing for the homeland, as in The Lusiads, is an undisputed theme of Pessoa’s verses as he spent most of his childhood in Durham, South Africa, with his family before returning to Portugal in 1905.

Pessoa wrote in Portuguese, English, and French and attained fame only after his death. He distinguished himself in his poetry and prose by employing what he called heteronyms, imaginary characters or alter egos written in different styles. While his three chief heteronyms were Alberto Caeiro, Ricardo Reis and Álvaro de Campos, scholars attribute more than 70 of these fictitious alter egos to Pessoa and many of these books can be encountered in library catalogs sometimes with no reference to Pessoa whatsoever. Use of identity as a flexible, dynamic construction, and his consequent rejection of traditional notions of authorship and individuality prefigure many of the concerns of postmodernism. He is widely considered one of the Portuguese language’s greatest poets and is required reading in most Portuguese literature programs.[3]

According to Ethnologue, there are over 234 million native Portuguese speakers in the world with the majority residing in Brazil.[4] Portuguese is the sixth most natively spoken language on the planet and the third most spoken European language in terms of native speakers.[5] Instruction in Portuguese language and culture has occurred primarily within the Department of Spanish & Portuguese. Since 1994, UC Berkeley’s Center for Portuguese Studies in collaboration with institutions in Portugal brings distinguished scholars to campus, sponsors conferences and workshops, develops courses, and supports research by students and faculty.

Contribution by Claude Potts

Librarian for Romance Language Collections, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Preface to Richard Zenith’s English translation Message. Lisboa: Oficina do Livro, 2016.

- Ibid.

- Portuguese (PORTUG) – Berkeley Academic Guide (accessed 2/4/20)

- Ethnoloque: Languages of the World (accessed 2/4/20)

- CIA World Factbook (accessed 2/4/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Mensagem

Title in English: Message

Author: Pessoa, Fernando, 1885-1935.

Imprint: Lisbon: Parceria António Maria Pereira, 1934.

Edition: 1st

Language: Portuguese

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal

URL: http://purl.pt/13966

Other online editions:

- Mensagem / Fernando Pessoa. – 1934. – [70] p. ; 22,2 x 14,7 cm. From Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal (BNP), http://purl.pt/13965.

- Mensagem. 1a ed. Lisboa : Pereira, 1934.

- Mensagem. Print facsimile from original manuscript in BNP. Lisboa : Babel, 2010.

- Mensagem. Comentada por Miguel Real ; ilustrações, João Pedro Lam. Lisboa : Parsifal, 2013.

- Mensagem : e outros poemas sobre Portugal. Fernando Cabral Martins and Richard Zenith, eds. Porto, Portugal : Assírio & Alvim, 2014.

- Mensagem. Translated into English by Richard Zenith. Illustrations by Pedro Sousa Pereira. Lisboa : Oficina do Livro, 2008

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Old/Middle Irish

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

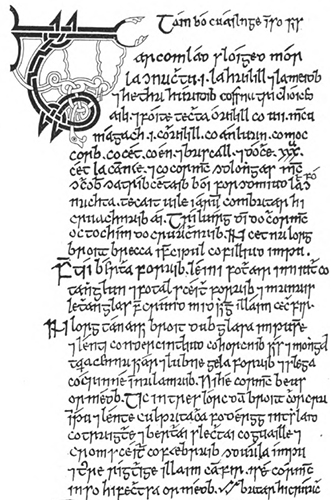

After Greek and Latin, Irish has the oldest literature in Europe, and Irish is the official language of the Republic of Ireland.[1] The prose epic Táin Bó Cúalnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley) narrates the battles of Irish legendary hero Cúchulainn as he single-handedly guards a prize bull from abduction by Queen Medb and her Connacht army. The tale is the most important in the broader mythology of the Ulster Cycle. The versions we know survive in fragments from medieval manuscripts (notably Lebor na hUidre, the oldest existing text in Irish, the Yellow Book of Lecan, and the Book of Leinster), but the story itself is most likely part of a pre-Christian oral tradition.

In the story, Queen Medb seeks to match her husband Ailill’s wealth through the acquisition of a bull, and she resorts to a raid after her attempt at trade falls through. Inconveniently, all the men in Ulster who might defend the bull have been cursed ill. Cúchulainn, the only man left standing, challenges warriors in Medb’s army to a series of one-on-one combats that culminates in a tragic three-day fight with his foster-brother and friend, Ferdiad. Along the way, Cúchulainn meets his father, the supernatural being Lugh; enjoys supernatural medical care; and transforms into a monster during his battle rages. After Ferdiad’s death, the Ulster men rally and bring the battle to a triumphant finish. Medb’s army is sent packing, but not before she succeeds in smuggling out the bull.

During the early 20th century, the Táin inspired Irish poets and writers such as Lady Gregory and William Butler Yeats, while Cúchulainn served as a symbol for Irish revolutionaries and Unionists alike. The Táin and its legends are routinely taught in UC Berkeley courses such as Medieval Celtic Culture, Celtic Mythology and Oral Tradition, and The World of the Celts. In 1911, the first North American degree-granting program in Celtic Languages and Literatures was founded at Berkeley, and the Celtic Studies Program continues to thrive today. Faculty from the departments of English, Rhetoric, Linguistics, and History participate in teaching regular courses in Irish and Welsh language and literature (in all their historical phases), and in the history, mythology, and cultures of the Celtic world. Breton is also offered regularly, and Gaulish, Cornish, Manx, and Scots Gaelic are foreseen as occasional offerings.[1]

Contribution by Stacy Reardon

Literatures and Digital Humanities Librarian, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Celtic Studies Program, UC Berkeley (accessed 1/27/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: “Táin Bó Cúalnge” in Leabhar na h-Uidhri

Title in English: Leabhar na h-uidhri: a collection of pieces in prose and verse, in the Irish language, comp. and transcribed about A.D. 1100, by Moelmuiri Mac Ceileachair: now for the first time pub. from the original in the library of the Royal Irish academy, with an account of the manuscript, a description of its contents, and an index.

Author: Anonymous prose epic

Imprint: Dublin, Royal Irish academy house, 1870.

Edition: 1st edition facsimile from original 8th century manuscript

Language: Old/Middle Irish

Language Family: Indo-European, Celtic

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (Cornell University)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001058698

Other online editions:

- Táin Bó Cúalnge from the Book of Leinster, Corpus of Electronic Texts (CELT).

https://celt.ucc.ie/published/G301035/index.html

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Fragments of the Táin in Atkinson, Robert. The Yellow Book of Lecan: A Collection of Pieces (prose and Verse) in the Irish Language, in Part Compiled at the End of the Fourteenth Century : Now for the First Time Published from the Original Manuscript in the Library of Trinity College. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1896.

- Recension of the Táin in Atkinson, Robert. The Book of Leinster, Sometime Called the Book of Glendalough: A Collection of Pieces (prose and Verse) in the Irish Language : Compiled in Part About the Middle of the Twelfth Century. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1880.

- The Táin. English translation by Thomas Kinsella and brush drawings by Louis Le Brocquy. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985.

- The Táin: A New Translation of the Táin Bó Cúailnge. English translation by Ciaran Carson. New York: Viking, 2008.

- Táin Bó Cúalnge, from the Book of Leinster. Annotated English edition by Cecile O’Rahilly. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1967.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Exhibit Reception – February 5, 2020

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

The UC Berkeley Library and the Berkeley Language Center

will hold a reception

for the online exhibition

with a special lecture

“The Promise of Multilingualism”

Judith Butler

Maxine Elliot Professor in the Department of Comparative Literature

& the Program of Critical Theory

2020 President of the Modern Language Association

and readings by

Emilie Bergmann for Spanish (Department of Spanish & Portuguese), Yael Chaver for Yiddish (Department of German), Jeroen Dewulf for Dutch (Department of German & Dutch Studies Program), Ahmad Diab for Arabic (Department of Near Eastern Studies, Robert Goldman for Sanskrit (Department of South and Southeast Asian Studies), Sam Mchombo for Chichewa (African American Studies), Deborah Rudolph for Chinese (C.V. Starr East Asian Library), Virginia Shih for Vietnamese (South/Southeast Asia Library), and Students in the Armenian Studies Program for Armenian.

Wednesday, February 5, 2020

5:00 pm – 7 :00pm

Morrison Library (110 Doe Library)

Seating is limited—please RSVP soon.

Refreshments will be served.

Sponsored by the UC Berkeley Library, Arts & Humanities Division and the Berkeley Language Center.

The Library attempts to offer programs in accessible, barrier-free settings.

If you think you may require disability-related accommodations , please contact libraryevents@berkeley.edu.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

www.ucblib.link/languages

Old Church Slavonic

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

According to the late Slavic linguist Horace Gray Lunt, “Slavonic or OCS is one of the Slavic languages that was used in the various geographical parts of the Slavic world for over two hundred years at the time when the Slavic languages were undergoing rapid, fundamental changes. Old Church Slavonic is the name given to the language of the oldest Slavic manuscripts, which date back to the 10th or 11th century. Since it is a literary language, used by the Slavs of many different regions, it represents not one regional dialect, but a generalized form of early Eastern Balkan Slavic (or Bulgaro-Macedonian) which cannot be specifically localized. It is important to cultural historians as the medium of Slavic Culture in the Middle Ages and to linguists as the earliest form of Slavic known, a form very close to the language called Proto-Slavic or Common Slavic which was presumably spoken by all Slavs before they became differentiated into separate nations.”[1]

At UC Berkeley, OCS has been taught regularly on a semester basis. Professor David Frick currently teaches it. His course description is as follows, “The focus of the course is straight forward, the goals are simple. We will spend much of our time on inflexional morphology (learning to produce and especially to identify the forms of the OCS nominal, verbal, participial, and adjectival forms). The goal will be to learn to read OCS texts, with the aid of dictionaries and grammars, by the end of the semester. We will discuss what the “canon” of OCS texts is and its relationship to “Church Slavonic” texts produced throughout the Orthodox Slavic world (and on the Dalmatian Coast) well into the eighteenth century. In this sense, the course is preparatory for any further work in premodern East and South Slavic cultures and languages.”[2]

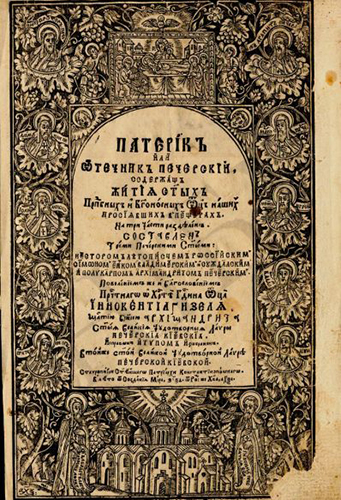

Kievsko-pecherskii paterik is a collection of essays written by different authors from different times. Researchers believe that initially, it consisted of two pieces of the bishop of Suzdal and Vladimir, Simon (1214-1226). One part was a “message” to a monk called Polycarp at the Kyivan cave monastery, and the other part was called the “word” on the establishment of the Assumption Church in Kyiv-Pechersk monastery. Later the book included some other works, such as “The Tale of the monk Crypt” from “Tale of Bygone Years” (1074), “Life” of St. Theodosius Pechersky and dedicated his “Eulogy.” It is in this line-up that “Paterik” represented the earliest manuscript, which was established in 1406 at the initiative of the Bishop of Tver Arsenii. In the 15th century, there were other manuscripts of the “Paterik” like the “Feodosievkaia” and “Kassianovskaia.” From the 17th century on, there were several versions of the printed text.

While there have been several re-editions of this particular book, this Patericon was reprinted in 1991 by Lybid in Kiev. WorldCat indexes ten instances including a 1967 edition that was published in Jordanville by the Holy Trinity Monastery.

Contribution by Liladhar Pendse

Librarian for East European and Central Asian Studies, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Lunt, Horace Gray. Old Church Slavonic Grammar. Berlin; Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, c. 2001, 2010.

- Frick, David. “Courses.” Old Church Slavic: Dept. of Slavic Languages and Literatures, UC Berkeley, slavic.berkeley.edu/courses/old-church-slavic-2. (accessed 1/20/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Paterik Kīevo-Pecherskoĭ : zhitīi︠a︡ svi︠a︡tykh

Title in English: Patericon or Paterikon of Kievan Cave: Lives of the Fathers

Author: Nestor, approximately 1056-1113., Simon, Bishop of Vladimir and Suzdal, 1214-1226., and Polikarp, Archimandrite, active 13th century.

Imprint: 17–? Kiev?

Edition: unknown

Language: Old Church Slavonic

Language Family: Indo-European, Slavic

Source: National Historical Library of Ukraine

URL: bit.ly/paterik

Other online editions:

- http://litopys.org.ua/paterikon/paterikon.htm (accessed 1/20/20)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Paterik Kīevo-Pecherskoĭ : zhitīi︠a︡ svi︠a︡tykh. Kīev : [s.n.], [17–?]. (accessed 1/20/20)

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Language of Music

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Music occupies a unique position in the field of languages in that it operates as both an independent language in itself and also as an element which can be combined with spoken/written languages to create musical settings of text. In the latter case, the juxtaposition of textual language and musical language produces a more complex, multi-faceted language which embodies the meaning and expressive qualities of both of its component languages.

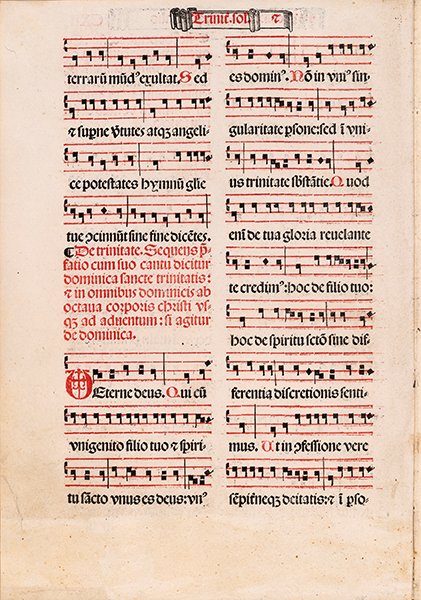

In the years BCE, music remained primarily an oral tradition, and although references to written music by some of the ancient Greek writers indicate the existence of notated music in their time, no extant examples of written music from the years BCE have been found. One of the earliest forms of Western musical notation, called Dasian notation, which first appeared in ninth century music treatises, was derived from signs used in ancient Greek prosody.[1] A system of symbols, called neumes, developed at about the same time to serve as a mnemonic tool to recall a previously memorized melody. Since most melodic tunes continued to be passed on through oral tradition at that time, neumes provided a way, albeit a limited way, to preserve existing tunes in written form. Around the beginning of the 11th century the system of neumes was expanded so that the notational symbols were written on a grid of four horizontal lines to indicate when pitches went up, down, or remained the same. Christian chant written during the late Medieval and early Renaissance periods made extensive use of this system of neumes, and the example provided in this exhibit from the Missale monasticum secundum, consuetudinem ordinis Vallisumbrose (1503) illustrates this early form of music notation. In the latter half of the 13th century, as musical notation continued to develop, the notational system expanded to indicate both pitch and the rhythmic value of pitches on a staff which, by that time, had expanded to five lines (except for chant notation, which, in most cases, continued to be written on four-line staves).

Verbal texts have been used as the basis of solo songs, vocal duets, trios and other ensembles of solo voices, as well as choral music for centuries, and it is not uncommon for a particular text to be set to music in original ways by multiple composers. Different musical settings can provide varied insights into the meaning of a text, or different interpretations of the text. Thus, music serves as a collaborative type of language which can be combined with verbal language to create an enriched, and sometimes complex, result. For example, the English bawdy song in Renaissance era was noted for presenting a text in a contrapuntal fashion in which multiple voices sang the same text, simultaneously, but at carefully paced intervals so that the words combined in different ways and created a significantly different meaning from the original text statement. The French composer Francis Poulenc was known to set well-established, serious, sacred texts to his own, personal style of music which was highly reminiscent of French dance hall music. (As an example, visit this link for a performance of Poulenc’s setting of the text Laudamus Te from his Gloria.)[2]

Of course, innumerable music works have been created that have no text component at all. Generally, this music can be divided into two categories: program music and absolute music. The former is conceived with an intended narrative association, and thus, communicates meaning as a language. Absolute music is composed without that narrative intention, but many listeners may still find meaning in this music even if it was not consciously intended by the composer. Examples of program music can be found throughout the literature from the time of the Renaissance and include such works as Andrea Gabrieli’s Battaglia, Antonio Vivaldi’s The Seasons, some of Joseph Haydn’s symphonies, and numerous tone poems from the 19th century.[3] The concept of absolute music, on the other hand, has been a topic of debate for more than a century. Many believe that certain musical works can be appreciated for their structure and design without any external associated meaning. While others believe that all music reveals (or, communicates) something about humanity, the human condition, human thought, etc. Examples of absolute music might include the Wohltemperierte Klavier of J.S. Bach, and the instrumental works of Anton Webern.[4] Numerous publications about absolute music are available for exploration.

As musical ideas have evolved, composers have changed the notation of music to accommodate ideas that could not be conveyed to the performers through traditional notational practices. The 19th and early 20th centuries brought a veritable explosion of expression markings to notated music in order to convey the composer’s expressive intentions to performers. Composers also sought new systems of musical notation to express their ideas, which often included media or performance techniques (such as “extended techniques,” electronic music notation, graphic notation, etc.) which had not been previously represented in the realm of music notation.[5] The French composer, Olivier Messiaen went so far as to invent an entire system of “translating” words and sentences into musical notation. His notation system is called langage communicable (“communicable language”). A summary of this system can be found on these two pages from the preface of his late organ cycle, Méditations sur le Mystère de la Sainte Trinité, where he introduced the system: (1) and (2).[6] In the 21st century musical notation continues to evolve and expand to accommodate the composer’s aural concepts as well as developing technologies.

The Jean Gray Hargrove Music Library at UC Berkeley provides a wealth of resource material for musicologists, music theorists, composers, performers, and other scholars in areas such as the history of music (including notation), the study of consonance and dissonance, studies in performance practice, and compositional studies of text setting, text painting, sound design, electronic music, and environmental sound. Hargrove’s special collections are world-renowned for their holdings in music primary source material dating from the early Renaissance and extending into the 20th century. Furthermore, the library’s print and media materials support studies in a wide variety of musical genres, including concert works, folk and popular music from around the world, rock music, and musical theatre. Concert music of the 20th and 21st centuries represented in the music collections include works based not only on highly organized procedures, such as those used in serialism, stochastic music, and computer-generated music, but also aleatoric and improvised music.

Contribution by Frank Ferko

Music Metadata Librarian, Jean Gray Hargrove Music Library

Source consulted:

- Grove Music Online, https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.07239, (accessed 11/19/19)

- YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ecwT4odGaZY, (accessed 11/19/19)

- YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1jD_pg-7tKY, (accessed 11/19/19)

- YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4bknpASD8c0, (accessed 11/19/19)

- “The art of visualising music,” http://davidhall.io/visualising-music-graphic-scores (accessed 11/19/19)

- http://www.robertkelleyphd.com/mespref1.jpg and http://www.robertkelleyphd.com/mespref2.jpg (accessed 11/19/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: “O Eterne deus” (from Missale monasticum secundum consuetudinem ordinis Vallisumbrose)

Title in English: O Eternal God

Composer: anonymous

Imprint: Venice : per Luca Antonio iuncta Florentino, 1503.

Language: Music

Source: Music Special Collections, University of California, Berkeley

Entire work: https://digicoll.lib.berkeley.edu/record/86261, See pages 254 or CXII (verso) and 256 or CXIII (recto).

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Missale mo[n]asticu[m] s[ecundu]m [con]suetudine[m] ordinis Vallisumbrose. Venetiis : per … Luca[m]antoniu[m] de giu[n]ta Flore[n]tinu[m], 1503. Music Case X. M2148.1.M5 V4 1503

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Italian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

It took centuries before Italy could codify and proclaim Italian as we know it today. The canonical author Dante Alighieri, was the first to dignify the Italian vernaculars in his De vulgari eloquentia (ca. 1302-1305). However, according to the Tuscan poet, no Italian city—not even Florence, his hometown—spoke a vernacular “sublime in learning and power, and capable of exalting those who use it in honour and glory.”[1] Dante, therefore, went on to compose his greatest work, the Divina Commedia in an illustrious Florentine which, unlike the vernacular spoken by the common people, was lofty and stylized. The Commedia (i.e. Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso) marked a linguistic and literary revolution at a time when Latin was the norm. Today, Dante and two other 14th-century Tuscan poets, Petrarch and Boccaccio, are known as the three crowns of Italian literature. Tuscany, particularly Florence, would become the cradle of the standard Italian language.

In his treatise Prose della volgar lingua (1525), the Venetian Pietro Bembo champions the Florentine of Petrarch and Boccaccio about 200 years earlier. Regardless of the ardent debates and disagreements that continued throughout the Renaissance and beyond, Bembo’s treatise encouraged many renowned poets and prose writers to compose their works in a Florentine that was no longer in use. Nevertheless, works continued to be written in many dialects for centuries (Milanese, Neapolitan, Sicilian, Sardinian, Venetian and many more), and such is the case until this day. But which language was to become the lingua franca throughout the newly formed Kingdom of Italy in 1861?

With Italy’s unification in the 19th century came a new mission: the need to adopt a common language for a population that had spoken their respective native dialects for generations.[2] In 1867, the mission fell to a committee led by Alessandro Manzoni, author of the bestselling historical novel I promessi sposi (The Betrothed, 1827). In 1868, he wrote to Italy’s minister of education Emilio Broglio that Tuscan, namely the Florentine spoken among the upper class, ought to be adopted. Over the years, in addition to the widespread adoption of The Betrothed as a model for modern Italian in schools, 20th-century Italian mass media (newspaper, radio, and television) became the major diffusers of a unifying national language.

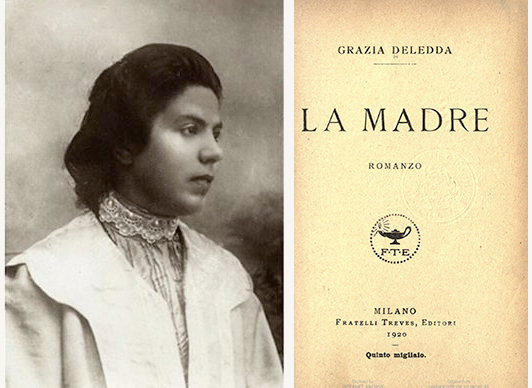

Grazia Maria Cosima Deledda (1871-1936), the author featured in this essay, is one of the millions of Italians who learned standardized Italian as a second language. Her maternal language was Logudorese Sardo, a variety of Sardinian. She took private lessons from her elementary school teacher and composed writing exercises in the form of short stories. Her first creations appeared in magazines, such as L’ultima moda between 1888 and 1889. She excelled in Standard Italian and confidently corresponded with publishers in Rome and Milan. During her lifetime, she published more than 50 works of fiction as well as poems, plays and essays, all of which invariably centered on what she knew best: the people, customs and landscapes of her native Sardinia.

The UC Berkeley Library houses approximately 265 books by and about Deledda as well as our digital editions of her novel La madre (The Mother). It was originally serialized for the newspaper Il tempo in 1919 and published in book form the following year. Deledda recounts the tragedy of three individuals: the protagonist Maria Maddalena, her son and young priest Paulo, and the lonely Agnese with whom Paulo falls in love. The mother is tormented at discovering her son’s love affair with Agnese. Three English translations of La madre have appeared, however, it was the 1922 translation by Mary G. Steegman (with a foreword by D.H. Lawrence) that was most influential in providing Deledda with international renown.

Deledda received the 1926 Nobel Prize for Literature “for her idealistically inspired writings which, with plastic clarity, picture the life on her native island and with depth and sympathy deal with human problems in general.”[3] To this day, she is the only Italian female writer to receive the highest prize in literature. Here are the opening lines of Deledda’s speech in occasion of the award conferment in 1927:

Sono nata in Sardegna. La mia famiglia, composta di gente savia ma anche di violenti e di artisti primitivi, aveva autorità e aveva anche biblioteca. Ma quando cominciai a scrivere, a tredici anni, fui contrariata dai miei. Il filosofo ammonisce: se tuo figlio scrive versi, correggilo e mandalo per la strada dei monti; se lo trovi nella poesia la seconda volta, puniscilo ancora; se va per la terza volta, lascialo in pace perché è un poeta. Senza vanità anche a me è capitato così.

I was born in Sardinia. My family, composed of wise people but also violent and unsophisticated artists, exercised authority and also kept a library. But when I started writing at age thirteen, I encountered opposition from my parents. As the philosopher warns: if your son writes verses, admonish him and send him to the mountain paths; if you find him composing poetry a second time, punish him once again; if he does it a third time, leave him alone because he’s a poet. Without pride, it happened to me the same way. [my translation]

The Department of Italian Studies at UC Berkeley dates back to the 1920s. Nevertheless, Italian was taught and studied long before the Department’s foundation. “Its faculty—permanent and visiting, present and past—includes some of the most distinguished scholars and representatives of Italy, its language, literature, history, and culture.” As one of the field’s leaders and innovators both in North America and internationally, the Department retains its long-established mission of teaching and promoting the language and literature of Italy and “has broadened its scope to include multiple disciplinary and interdisciplinary perspectives to view the country, its language, and its people” from within Italy and globally, from the Middle Ages to the present day.[4]

Contribution by Brenda Rosado

PhD Student, Department of Italian Studies

Source consulted:

- Dante Alighieri, De Vulgari Eloquentia, Ed. and Trans. Steven Botterill, p. 41

- Mappa delle lingue e gruppi dialettali d’italiani, Wikimedia Commons (accessed 12/5/19)

- From Nobel Prize official website: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1926/summary

See also the award presentation speech (on December 10, 1927) by Henrik Schück, President of the Nobel Foundation: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1926/ceremony-speech (accessed 12/5/19) - Department of Italian Studies, UC Berkeley (accessed 12/5/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: La madre

Title in English: The Woman and the Priest

Author: Deledda, Grazia, 1871-1936

Imprint: Milano : Treves, 1920.

Edition: 1st

Language: Italian

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: HathiTrust (University of California)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006136134

Other online editions:

- La madre. 1st ed. Milano : Treves, 1920. (Sardegna Digital Library)

- The Woman and the Priest. Translated into English by M.G. Steegman; foreword by D.H. Lawrence. London, J. Cape, 1922. (HathiTrust)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- La madre. 1st ed. Milano : Treves, 1920.

- La Madre : (The woman and the priest), or, The mother. Translated into English by M.G. Steegman; foreword by D.H. Lawrence; with an introduction and chronology by Eric Lane. London : Dedalus, 1987.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)