Romance Language Collections

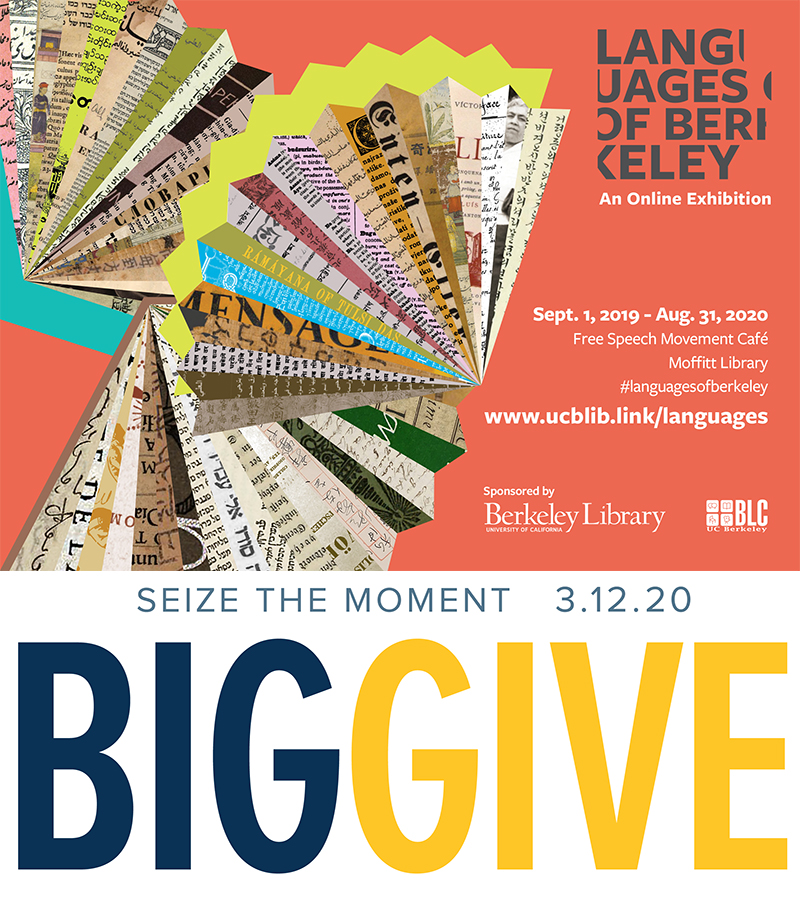

Give Big to Languages at Berkeley

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Support research, teaching, and learning of diverse non-English languages at UC Berkeley today. #CalBigGive

Support research, teaching, and learning of diverse non-English languages at UC Berkeley today. #CalBigGive

Art History/Classics Library Fund

University Library

East Asian Library Fund

University Library

South/Southeast Asian Library Fund

University Library

Library Collections Fund

University Library

Berkeley Language Center Fund

College of Letters & Science

Visit biggive.berkeley.edu for other library fundraising programs.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

http://ucblib.link/languages

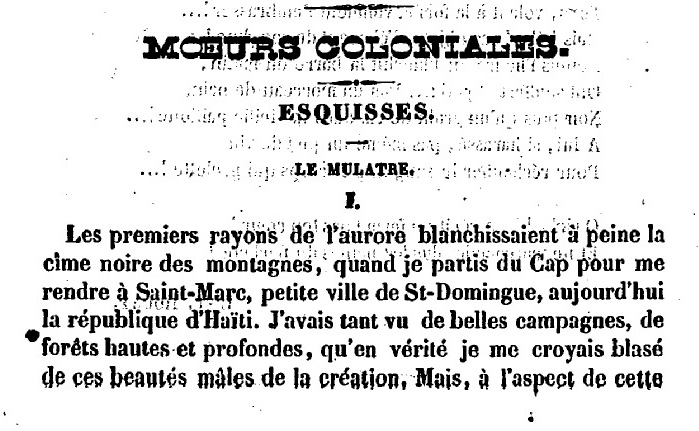

An African American short story in French

Born in New Orleans, Victor Séjour (1817-1874) was a Creole writer who moved to France at the age of 19 to continue his education, find work, and flee the racial oppression of Louisiana. His short story “Le Mulâtre” (“The Mulatto”) was first published in the abolitionist journal Révue des Colonies (March 1837) not long after his arrival in Paris and is now freely available through Gallica—the digital library of the Bibliothèque nationale de France. It is the first work of fiction written by an African American author. Set in Saint Domingue before the Haitian Revolution, Séjour’s work centers on the injustice and cruelty of slavery. According to Marlene Daut and David O’Connell in her article “Sons of White Fathers: Mulatto Vengeance and the Haitian Revolution in Victor Séjour’s ‘The Mulatto'” published in Nineteenth-Century Literature 65:1 (June 2010), the tale was “not simply a blow . . . struck for the cause of abolition in the French colonies, but [was] . . . also one of the first manifestations of a ‘literature of combat’ written by an American black.””

Born in New Orleans, Victor Séjour (1817-1874) was a Creole writer who moved to France at the age of 19 to continue his education, find work, and flee the racial oppression of Louisiana. His short story “Le Mulâtre” (“The Mulatto”) was first published in the abolitionist journal Révue des Colonies (March 1837) not long after his arrival in Paris and is now freely available through Gallica—the digital library of the Bibliothèque nationale de France. It is the first work of fiction written by an African American author. Set in Saint Domingue before the Haitian Revolution, Séjour’s work centers on the injustice and cruelty of slavery. According to Marlene Daut and David O’Connell in her article “Sons of White Fathers: Mulatto Vengeance and the Haitian Revolution in Victor Séjour’s ‘The Mulatto'” published in Nineteenth-Century Literature 65:1 (June 2010), the tale was “not simply a blow . . . struck for the cause of abolition in the French colonies, but [was] . . . also one of the first manifestations of a ‘literature of combat’ written by an American black.””

A full English translation of “The Mulatto” was published more than one hundred years after his death in The Norton Anthology of African American Literature, edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Nellie Y. McKay (New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 1997). Remembered as one of the first black writers of both the African American and French literary traditions, Victor Séjour enjoyed a period of success as a playwright, was naturalized as a French citizen, and is buried in the Père-Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. The Library has reprints in French and a few English translations of his works in the Main Stacks while The Bancroft Library houses two rare first editions – La madone des roses : drame en cinq actes, en prose (1869) and La tireuse de cartes; drame en cinq actes et un prologue, en prose (1860) in its African American Writers collection.

This post has been shared as part of a UC Berkeley initiative announced by Chancellor Carol Christ to mark the 400th anniversary of the forced arrival of enslaved Africans in the English colonies.

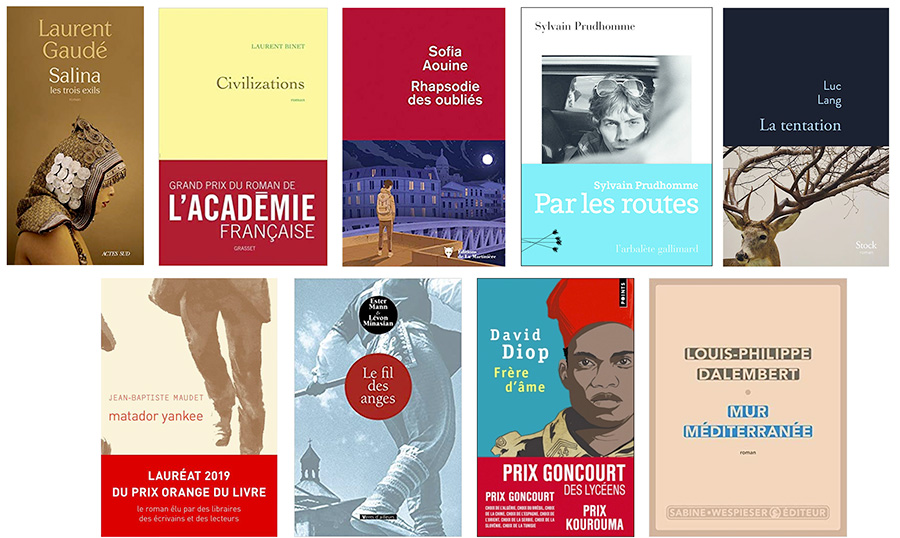

French Literary Prize Winners 2019

France’s array of literary prizes offer a glimpse of emerging French and francophone writers, and also award accolades to the well-known. The winning titles with hyperlinks on this list provided by Amalivre in Paris are now available for check-out in UC Berkeley’s collection. To view the most recent book purchases across disciplines within French studies, please consult the recent acquisitions list in OskiCat.

| Fall Awards | Author | Title | Publisher | ||

| Governor General’s Literary Award (roman français) | * | Céline Huyghebaert | Le drap blanc | Le Quartanier | |

| Grand prix de la littérature policière | * | Richard Morgiève | Le Cherokee | Joëlle Losfeld | |

| Grand prix du roman de l’Académie Française | * | Laurent Binet | Civilizations | Grasset | |

| Grand prix du roman métis | * | Laurent Gaudé | Salina: les trois exils | Actes sud | |

| Prix Décembre | * | Claudie Hunziger | Les grands cerfs | Grasset | |

| Prix de Flore | Sofia Aouine | Rhapsodie des oubliés | La Martinière | ||

| Prix de la langue française | * | Louis-Philippe Dalembert | Mur méditerranée | Sabine Wespieser | |

| Prix de la nouvelle de l’Académie française | * | Louis-Antoine Prat | Belle encore et autres nouvelles | Somogy | |

| Prix des cinq continents de la francophonie | * | Gilles Jobidon | Le tranquille affligé | Leméac | |

| Prix du roman FNAC | * | Bérengère Cournut | De pierre et d’os | Le Tripode | |

| Prix Femina | * | Sylvain Prudhomme | Par les routes | Gallimard | |

| Prix Femina essai | * | Emmanuelle Lambert | Giono, furioso | Stock | |

| Prix Goncourt | * | Jean-Paul Dubois | Tous les hommes n’habitent pas le monde de la même façon | L’Olivier | |

| Prix Goncourt des lycéens | * | Karine Tuil | Les choses humaines | Gallimard | |

| Prix Guillaume Apollinaire (Poetry) | * | Olivier Barbarant | Un grand instant | Champ Vallon | |

| Prix Interallié | * | Karine Tuil | Les choses humaines | Gallimard | |

| Prix Landernau | * | Sylvain Prudhomme | Par les routes | Gallimard | |

| Prix Médicis | * | Luc Lang | La tentation | Stock | |

| Prix Médicis essai | * | Bulle Ogier & Anne Diatkine | J’ai oublié | Seuil | |

| Prix Renaudot | * | Sylvain Tesson | La panthère des neiges | Gallimard | |

| Prix Renaudot des lycéens | * | Victoria Mas | Le bal des folles | Albin Michel | |

| Prix Renaudot essai | * | Eric Neuhoff | (Très) cher cinéma français | Albin Michel | |

| Prix Senghor du premier roman francophone | * |

Ester Mann & Levon Minassian

|

Le fil des anges | Vents d’ailleurs | |

| Prix Wepler | * | Lucie Taïeb | Les échappées | Editions de l’Ogre | |

| Other General Literary Prizes | |||||

| Prix des Deux Magots (January) | * | Emmanuel de Waresquiel | Le temps de s’en apercevoir | L’Iconoclaste | |

| Prix des Libraires (June) | * | Franck Bouysse | Né d’aucune femme |

La Manufacture de Livres

|

|

| Grand prix de la francophonie de l’Académie Française | * | ||||

| Grand prix littéraire de l’Afrique noire (May) | * | Armand Gauz | Camarade Papa | Nouvel Attila | |

| Prix Goncourt du Premier Roman (May) | * | Marie Gauthier | Court vêtue | Gallimard | |

| Prix Goncourt de la nouvelle | * | Caroline Lamarche | Nous sommes à la lisière | Gallimard | |

| Prix Ahmadou Kourouma (May) | * | David Diop | Frère d’âme | ||

| Prix Goncourt de la poésie (May) | * | Yvon Le Men | awarded for the body of his work | ||

| Prix Goncourt de la biographie (June) | * | Frédéric Pajak | Manifeste incertain 7 | Noir sur blanc | |

| Prix Landernau Polar (May) | * | Thomas Canteloube | Réquiem pour une République | Gallimard | |

| European Union Prize for Literature (auteurs français) | * | Sophie Daull | awarded for the ensemble of her work | Ed. Philippe Rey | |

| Prix Mallarmé (Poetry) | * | Claudine Bohi | Naître, c’est longtemps | La tête à l’envers | |

| Prix Orange (June) | * | Jean-Baptiste Maudet | Matador Yankee | Le Passage | |

| Prix de l’Académie française Maurice Genevoix (June) | * | Jean-Marie Planes | Une vie de soleil | Arléa | |

| Prix Ouest France Etonnants Voyageurs (June) | * | Anaïs Llobet | Des hommes couleur de ciel | Ed. de l’Observatoire | |

| Prix des Lecteurs de L’Express (June) | * | Jean-Claude Grumberg | La plus précieuse des marchandises | Seuil | |

| Prix Jean d’Ormesson (new 2018 –not restricted to living authors or new titles) | * | Julian Barnes | La seule histoire (translated from the English) | Gallimard | |

| Grand Prix de Poésie de l’Académie française | * | Pierre Oster | For the ensemble of his work | ||

| Prix de la Bibliothèque nationale de France (June) | * | Virginie Despentes | For the ensemble of her work | ||

| Prix du livre Inter (June) | * | Emmanuelle Bayamack-Tam | Arcadie | POL |

Portuguese

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

Ó mar salgado, quanto do teu sal

São lágrimas de Portugal!

Quando virás, ó Encoberto,

Sonho das eras portuguez,

Tornar-me mais que o sopro incerto

De um grande anceio que Deus fez?

O salty sea, so much of whose salt

Is Portugal’s tears!

When will you come home, O Hidden One,

Portuguese dream of every age,

To make me more than faint breath

Of an ardent, God-created yearning?

(Trans. Richard Zenith, Message)

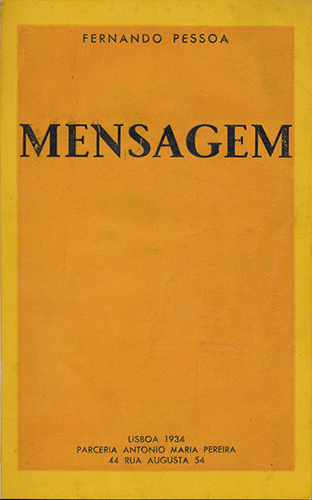

Living in a paradoxical era of artistic experimentalism and political authoritarianism, Fernando António Nogueira Pêssoa (1888-1935) is considered Portugal’s most important modern writer. Born in Lisbon, he was a poet, writer, literary critic, translator, publisher and philosopher. Most of his creative output appeared in journals. He published just one book in his lifetime in his native language Mensagem (“Message”). In the same year this collection of 44 poems was published, António Salazar was consolidating his Estado Novo (“New State”) regime, which would subjugate the nation and its colonies in Africa for more than 40 years. Encouraged to submit Mensagem by António Ferro, a colleague with whom he previously collaborated in the literary journal Orpheu (1915), Pessoa was awarded the poetry prize sponsored by the National Office of Propaganda for the work’s “lofty sense of nationalist exhaltation.”[1]

Because of its association with the Salazar’s dictatorship, Mensagem was regarded as a national monument but also as something reprehensible. Translator Richard Zenith describes it as a “lyrical expansion on The Lusiads, Camões’ great epic celebration of the Portuguese discoveries epitomized by Vasco de Gama’s inaugural voyage to India.”[2] At the same time, it traces an intimate connection to the world at large, or rather, to various worlds (historical, psychological, imaginary, spriritual) beginning with the circumscribed existence of Pessoa as a child. Longing for the homeland, as in The Lusiads, is an undisputed theme of Pessoa’s verses as he spent most of his childhood in Durham, South Africa, with his family before returning to Portugal in 1905.

Pessoa wrote in Portuguese, English, and French and attained fame only after his death. He distinguished himself in his poetry and prose by employing what he called heteronyms, imaginary characters or alter egos written in different styles. While his three chief heteronyms were Alberto Caeiro, Ricardo Reis and Álvaro de Campos, scholars attribute more than 70 of these fictitious alter egos to Pessoa and many of these books can be encountered in library catalogs sometimes with no reference to Pessoa whatsoever. Use of identity as a flexible, dynamic construction, and his consequent rejection of traditional notions of authorship and individuality prefigure many of the concerns of postmodernism. He is widely considered one of the Portuguese language’s greatest poets and is required reading in most Portuguese literature programs.[3]

According to Ethnologue, there are over 234 million native Portuguese speakers in the world with the majority residing in Brazil.[4] Portuguese is the sixth most natively spoken language on the planet and the third most spoken European language in terms of native speakers.[5] Instruction in Portuguese language and culture has occurred primarily within the Department of Spanish & Portuguese. Since 1994, UC Berkeley’s Center for Portuguese Studies in collaboration with institutions in Portugal brings distinguished scholars to campus, sponsors conferences and workshops, develops courses, and supports research by students and faculty.

Contribution by Claude Potts

Librarian for Romance Language Collections, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Preface to Richard Zenith’s English translation Message. Lisboa: Oficina do Livro, 2016.

- Ibid.

- Portuguese (PORTUG) – Berkeley Academic Guide (accessed 2/4/20)

- Ethnoloque: Languages of the World (accessed 2/4/20)

- CIA World Factbook (accessed 2/4/20)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Mensagem

Title in English: Message

Author: Pessoa, Fernando, 1885-1935.

Imprint: Lisbon: Parceria António Maria Pereira, 1934.

Edition: 1st

Language: Portuguese

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal

URL: http://purl.pt/13966

Other online editions:

- Mensagem / Fernando Pessoa. – 1934. – [70] p. ; 22,2 x 14,7 cm. From Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal (BNP), http://purl.pt/13965.

- Mensagem. 1a ed. Lisboa : Pereira, 1934.

- Mensagem. Print facsimile from original manuscript in BNP. Lisboa : Babel, 2010.

- Mensagem. Comentada por Miguel Real ; ilustrações, João Pedro Lam. Lisboa : Parsifal, 2013.

- Mensagem : e outros poemas sobre Portugal. Fernando Cabral Martins and Richard Zenith, eds. Porto, Portugal : Assírio & Alvim, 2014.

- Mensagem. Translated into English by Richard Zenith. Illustrations by Pedro Sousa Pereira. Lisboa : Oficina do Livro, 2008

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Italian

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

It took centuries before Italy could codify and proclaim Italian as we know it today. The canonical author Dante Alighieri, was the first to dignify the Italian vernaculars in his De vulgari eloquentia (ca. 1302-1305). However, according to the Tuscan poet, no Italian city—not even Florence, his hometown—spoke a vernacular “sublime in learning and power, and capable of exalting those who use it in honour and glory.”[1] Dante, therefore, went on to compose his greatest work, the Divina Commedia in an illustrious Florentine which, unlike the vernacular spoken by the common people, was lofty and stylized. The Commedia (i.e. Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso) marked a linguistic and literary revolution at a time when Latin was the norm. Today, Dante and two other 14th-century Tuscan poets, Petrarch and Boccaccio, are known as the three crowns of Italian literature. Tuscany, particularly Florence, would become the cradle of the standard Italian language.

In his treatise Prose della volgar lingua (1525), the Venetian Pietro Bembo champions the Florentine of Petrarch and Boccaccio about 200 years earlier. Regardless of the ardent debates and disagreements that continued throughout the Renaissance and beyond, Bembo’s treatise encouraged many renowned poets and prose writers to compose their works in a Florentine that was no longer in use. Nevertheless, works continued to be written in many dialects for centuries (Milanese, Neapolitan, Sicilian, Sardinian, Venetian and many more), and such is the case until this day. But which language was to become the lingua franca throughout the newly formed Kingdom of Italy in 1861?

With Italy’s unification in the 19th century came a new mission: the need to adopt a common language for a population that had spoken their respective native dialects for generations.[2] In 1867, the mission fell to a committee led by Alessandro Manzoni, author of the bestselling historical novel I promessi sposi (The Betrothed, 1827). In 1868, he wrote to Italy’s minister of education Emilio Broglio that Tuscan, namely the Florentine spoken among the upper class, ought to be adopted. Over the years, in addition to the widespread adoption of The Betrothed as a model for modern Italian in schools, 20th-century Italian mass media (newspaper, radio, and television) became the major diffusers of a unifying national language.

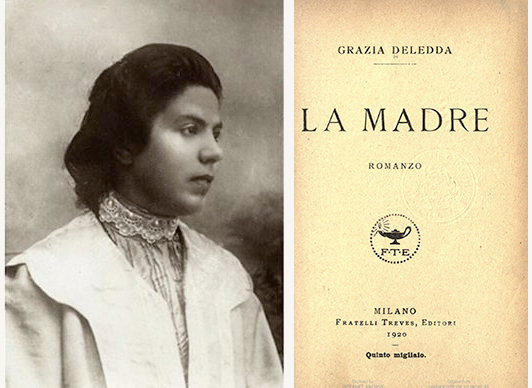

Grazia Maria Cosima Deledda (1871-1936), the author featured in this essay, is one of the millions of Italians who learned standardized Italian as a second language. Her maternal language was Logudorese Sardo, a variety of Sardinian. She took private lessons from her elementary school teacher and composed writing exercises in the form of short stories. Her first creations appeared in magazines, such as L’ultima moda between 1888 and 1889. She excelled in Standard Italian and confidently corresponded with publishers in Rome and Milan. During her lifetime, she published more than 50 works of fiction as well as poems, plays and essays, all of which invariably centered on what she knew best: the people, customs and landscapes of her native Sardinia.

The UC Berkeley Library houses approximately 265 books by and about Deledda as well as our digital editions of her novel La madre (The Mother). It was originally serialized for the newspaper Il tempo in 1919 and published in book form the following year. Deledda recounts the tragedy of three individuals: the protagonist Maria Maddalena, her son and young priest Paulo, and the lonely Agnese with whom Paulo falls in love. The mother is tormented at discovering her son’s love affair with Agnese. Three English translations of La madre have appeared, however, it was the 1922 translation by Mary G. Steegman (with a foreword by D.H. Lawrence) that was most influential in providing Deledda with international renown.

Deledda received the 1926 Nobel Prize for Literature “for her idealistically inspired writings which, with plastic clarity, picture the life on her native island and with depth and sympathy deal with human problems in general.”[3] To this day, she is the only Italian female writer to receive the highest prize in literature. Here are the opening lines of Deledda’s speech in occasion of the award conferment in 1927:

Sono nata in Sardegna. La mia famiglia, composta di gente savia ma anche di violenti e di artisti primitivi, aveva autorità e aveva anche biblioteca. Ma quando cominciai a scrivere, a tredici anni, fui contrariata dai miei. Il filosofo ammonisce: se tuo figlio scrive versi, correggilo e mandalo per la strada dei monti; se lo trovi nella poesia la seconda volta, puniscilo ancora; se va per la terza volta, lascialo in pace perché è un poeta. Senza vanità anche a me è capitato così.

I was born in Sardinia. My family, composed of wise people but also violent and unsophisticated artists, exercised authority and also kept a library. But when I started writing at age thirteen, I encountered opposition from my parents. As the philosopher warns: if your son writes verses, admonish him and send him to the mountain paths; if you find him composing poetry a second time, punish him once again; if he does it a third time, leave him alone because he’s a poet. Without pride, it happened to me the same way. [my translation]

The Department of Italian Studies at UC Berkeley dates back to the 1920s. Nevertheless, Italian was taught and studied long before the Department’s foundation. “Its faculty—permanent and visiting, present and past—includes some of the most distinguished scholars and representatives of Italy, its language, literature, history, and culture.” As one of the field’s leaders and innovators both in North America and internationally, the Department retains its long-established mission of teaching and promoting the language and literature of Italy and “has broadened its scope to include multiple disciplinary and interdisciplinary perspectives to view the country, its language, and its people” from within Italy and globally, from the Middle Ages to the present day.[4]

Contribution by Brenda Rosado

PhD Student, Department of Italian Studies

Source consulted:

- Dante Alighieri, De Vulgari Eloquentia, Ed. and Trans. Steven Botterill, p. 41

- Mappa delle lingue e gruppi dialettali d’italiani, Wikimedia Commons (accessed 12/5/19)

- From Nobel Prize official website: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1926/summary

See also the award presentation speech (on December 10, 1927) by Henrik Schück, President of the Nobel Foundation: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1926/ceremony-speech (accessed 12/5/19) - Department of Italian Studies, UC Berkeley (accessed 12/5/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: La madre

Title in English: The Woman and the Priest

Author: Deledda, Grazia, 1871-1936

Imprint: Milano : Treves, 1920.

Edition: 1st

Language: Italian

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: HathiTrust (University of California)

URL: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006136134

Other online editions:

- La madre. 1st ed. Milano : Treves, 1920. (Sardegna Digital Library)

- The Woman and the Priest. Translated into English by M.G. Steegman; foreword by D.H. Lawrence. London, J. Cape, 1922. (HathiTrust)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- La madre. 1st ed. Milano : Treves, 1920.

- La Madre : (The woman and the priest), or, The mother. Translated into English by M.G. Steegman; foreword by D.H. Lawrence; with an introduction and chronology by Eric Lane. London : Dedalus, 1987.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Occitan

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

A Lamartine:

Te consacre Mirèio : es moun cor e moun amo,

Es la flour de mis an,

Es un rasin de Crau qu’emé touto sa ramo

Te porge un païsan.

To Lamartine :

To you I dedicate Mirèio: ‘tis my heart and soul,

It is the flower of my years;

It is a bunch of Crau grapes,

Which with all its leaves a peasant brings you. (Trans. C. Grant)

On May 21, 1854, seven poets met at the Château de Font-Ségugne in Provence, and dubbed themselves the “Félibrige” (from the Provençal felibre, whose disputed etymology is usually given as “pupil”). Their literary society had a larger goal: to restore glory to their language, Provençal. The language was in decline, stigmatized as a backwards rural patois. All seven members of the Félibrige, and those who have taken up their mantle through the present day, labored to restore the prestige to which they felt Provençal was due as a literary language. None was more successful or celebrated than Frédéric Mistral (1830-1914).

Mirèio, which Mistral referred to simply as a “Provençal poem,” is composed of 12 cantos and was published in 1859. Mirèio, the daughter of a wealthy farmer, falls in love with Vincèn, a basketweaver. Vincèn’s simple yet noble occupation and Mirèio’s modest dignity and devotion mark them as embodiments of the country virtues so prized by the Félibrige. Mirèio embarks on a journey to Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, that she might pray for her father to accept Vincèn. Her quest ends in tragedy, but Mistral’s finely drawn portraits of the characters and landscapes of beloved Provence, and of the implacable power of love still linger. C.M. Girdlestone praises the regional specificity and the universality of Mistral’s oeuvre thus: “Written for the ‘shepherds and peasants’ of Provence, his work, on the wings of its transcendant loveliness, reaches out to all men.”[1]

Mistral distinguished himself as a poet and as a lexicographer. He produced an authoritative dictionary of Provençal, Lou tresor dóu Felibrige. He wrote four long narrative poems over his lifetime: Mirèio, Calendal, Nerto, and Lou Pouemo dóu Rose. His other literary work includes lyric poems, short stories, and a well-received book of memoirs titled Moun espelido. Frédéric Mistral won a Nobel Prize in literature in 1904 “in recognition of the fresh originality and true inspiration of his poetic production, which faithfully reflects the natural scenery and native spirit of his people, and, in addition, his significant work as a Provençal philologist.”[2]

Today, Provençal is considered variously to be a language in its own right or a dialect of Occitan. The latter label encompasses the Romance varieties spoken across the southern third of France, Spain’s Val d’Aran, and Italy’s Piedmont valleys. The Félibrige is still active as a language revival association.[3] Along with myriad other groups and individuals, it advocates for the continued survival and flowering of regional languages in southern France.

Contribution by Elyse Ritchey

PhD student, Romance Languages and Literatures

Source consulted:

- Girdlestone, C.M. Dreamer and Striver: The Poetry of Frédéric Mistral. London: Methuen, 1937.

- “Frédéric Mistral: Facts.” The Nobel Prize. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1904/mistral/facts. (accessed 11/12/19)

- Felibrige, http://www.felibrige.org (accessed 11/12/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Mirèio

Title in English: Mirèio / Mireille

Author: Mistral, Frédéric, 1830-1914

Imprint: Paris: Charpentier, 1861.

Edition: 2nd

Language: Occitan with parallel French translation

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Gallica (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k64555655

Other online editions::

- An English version (the original crowned by the French academy) of Frédéric Mistral’s Mirèio from the original Proven̨cal under the author’s sanction. Avignon : J. Roumanille, 1867. HathiTrust

- Mireille, poème provençal avec la traduction littérale en regard. Paris, Charpentier, 1898. HathiTrust

- Mirèio : A Provençal poem. Translated into English by Harriet Waters Preston. London, T.F. Unwin, 1890. Internet Archive (UC Riverside)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Mireille : poème provençal. Traduit en vers français par E. Rigaud. Paris : Librairie Hachette, 1881.

- Mireio : pouemo prouvencau, avec la traduction littérale en regard. Paris : Charpentier, 1888.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

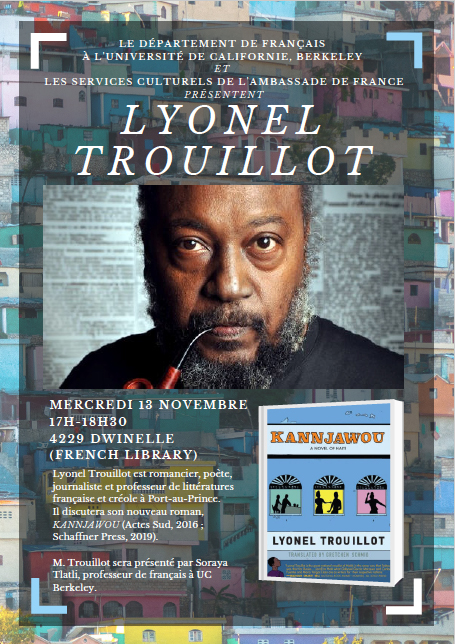

Book talk (en français) with Lyonel Trouillot

Wednesday, November 13

5-6:30 pm

4229 Dwinelle (French Department Library)

Lyonel Trouillot is a novelist, poet, journalist and professor of French and Creole literatures in Port-au-Prince. He will discuss his novel Kannjawou (Actes Sud, 2016) which was recently translated into English (Schaffner Press, 2019). He will be introduced by Soraya Tlatli, professor of French at UC Berkeley.

Sponsored by UC Berkeley’s Department of French

&

Cultural Services, French Embassy in the U.S.

Featured Publisher – Edizioni e/o

The independent publishing house Edizioni e/o was founded in Rome in 1979 by Sandro Ferria and Sandra Ozzola who had a profound interest in cultural dialogue and exchange. Early on they focused on literary translations into Italian, particularly with writers from Eastern Europe, but soon began to publish writers from their own country as Lia Levi, Gioconda Belli, and Elena Ferrante. In 2005, the founders launched Europa Editions which brings into the English-speaking world some of the Europe’s best contemporary writers. Here are a few of the latest Edizioni e/o titles in Italian that can be found in Berkeley’s collection:

Lia Levi

Tiziana de Rogatis

Patrizia Rinaldi

Roberto Tiraboschi

Caterina Emili (on order)

Massimo Carlotto

Spanish (Europe)

The Languages of Berkeley: An Online Exhibition

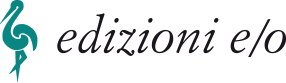

If you walk down the street in many parts of the world and ask a stranger who fought the windmills, they would most probably answer Don Quixote. But they would not necessarily know the name of its author, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1547-1616). This not-so-prolific dramaturge, poet and novelist has nonetheless had a major impact on the development of Western literature, influencing his English contemporary William Shakespeare, 19th-century French author Gustave Flaubert, and 20th-century Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges, just to name a few.

Cervantes did not come to prominence until much later in his life. His experiences as a soldier, a captive and a witness to the struggles of the Spanish empire shaped his distinctive oeuvre: a literary world of experimentation, as can be seen in his Exemplary Novels (1613), a world in which possibilities of reconciliation between conflictive individuals, ideals and desires remained hollow, inconclusive and, in many cases, without avail. Among other factors, what distinguishes Cervantes’ literary production is its unclassifiable nature, making it hard to try and fit the works in their presumed corresponding genre. One good example is his posthumous work The Travails of Persiles and Sigismunda (1616), where the Byzantine novel is mutilated to such an extent that, at points, it becomes almost unrecognizable.

Yet this unfittedness is most evident in Don Quixote (Part I published in 1605; Part II in 1615). The confusion between reality and fiction, the untrustworthiness of the multiple narrators, the intentional errors and misnomers, the three-dimensionalism of Don Quixote’s squire, Sancho, who has a love-hate relationship with his master, the utter destruction of the chivalric world, and the encounter with oppressed minorities are but some of the factors that have undoubtedly contributed to the sustained appeal of Don Quixote. The protagonist, an old man who “loses his mind” reading novels of chivalry, was, in Western literature, a pioneering self-proclaimed “hero.” He offers and imposes his help unto people who rarely take him seriously. Moreover, he only becomes popular, within his diegetic world, when in Part II he is defined by others as a caricature. This caricature remains dominant in the collective imaginary of readers, as can be seen, for example, in Picasso’s well-known depiction of the character.

Although most masterpieces ultimately attempt to challenge a comfortable experience of reading where we readily identify with fictitious characters; Don Quixote still manages to attract the empathy of its readers who may or may not closely identify with the knight-errant. Don Quixote is beaten up, both physically and metaphorically, yet his innocent, albeit selfish at times, intentions have ultimately won the hearts of a diverse audience over the centuries.

Today, the Spanish language, or Castilian as it is referred to in Europe, has grown from around 14 million speakers at the time of Cervantes to 477 million native speakers worldwide. It is now the second most used language for international communication and the most studied languages on the planet.[1] At Berkeley, Spanish is one of the most widely used languages for scholarship after English, particularly in departments such as Anthropology, Comparative Literature, Ethnic Studies, Film & Media, Gender & Women’s Studies, History, Linguistics, Political Science, and Rhetoric. Interdisciplinary graduate programs in Latin American Studies, Medieval Studies, Romance Languages and Literature, and Medieval and Early Modern Studies also require reading of original texts in Spanish.

Nasser Meerkhan, Assistant Professor

Department of Near Eastern Studies & Department of Spanish & Portuguese

Source consulted:

- Elias, D. José Antonio. Atlas historico, geográfico y estadístico de España y sus posesiones de ultramar. Barcelona : Imprenta Hispana, 1848; Hernández Sánchez Barbara, Mario. “La población hispanoamericana y su distribución social en el siglo XVIII,” Revista de estudios políticos, no.78 (1954); López, Morales H, and El español: una lengua viva. Informe 2017. Madrid : Arco Libros, S.L. : El Instituto, 2017.

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha

Author: Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de, 1547-1616.

Imprint: En Madrid : por Iuan de la Cuesta, 1605, 1615.

Edition: 1st

Language: Spanish (Europe)

Language Family: Indo-European

Source: Biblioteca Nacional de España

URL: http://quijote.bne.es/libro.html (requires Flash)

Other online editions:

- El ingenioso hidalgo don Quixote de la Mancha / compuesto por Miguel de Ceruantes Saauedra. En Madrid : por Iuan de la Cuesta, 1605.

- Segunda parte del ingenioso cauallero don Quixote de la Mancha / por Miguel de Ceruantes Saauedra, autor de su primera parte. En Madrid : por Iuan de la Cuesta, 1615.

- The History of Don Quixote. Translated into English by J.W. Clark. Illustrated by Gustave Doré. New York, P.F. Collier, 1871 .

Select print editions at Berkeley:

Considered to be the most translated work every written, the Library has editions in French, German, Hebrew, Armenian, Quechua, and more. The earliest and best illustrated editions reside in The Bancroft Library.

- El ingenioso hidalgo don Quixote de la Mancha. Burgaillos. Published Impresso con licencia, en Valencia : En casa de Pedro Patricio Mey : A costa de Iusepe Ferrer mercader de libros, delante la Diputacion, 1605.

- Segunda parte del ingenioso cauallero don Quixote de la Mancha. En Valencia : En casa de Pedro Patricio Mey, junto a San Martin : A costa de Roque Sonzonio mercader de libros, 1616.

- Vida y hechos del ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha. Nueva edicion, corregida y ilustrada con 32 differentes estampas muy donosas, y apropriadas à la materia. Amberes, Por Henrico y Cornelio Verdussen, 1719.

- El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha / por Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra ; obra adornada de 125 estampas litográficas y publicada por Masse y Decaen, impresore litógrafos y editores, callejon de Santa Clara no 8. México : Impreso por Ignacio Cumplido, calle de los Rebeldes num. 2, 1842.

- Don Quixote / Miguel de Cervantes ; a new translation by Edith Grossman ; introduction by Harold Bloom. New York : Ecco, c2003.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

Romance Language Collections Newsletter no.4 (Fall 2019)

Welcome back to campus everyone! This newsletter provides an overview of library services and new scholarly resources added in the past year with a focus on the Romance languages and southern European studies in particular.

New Electronic Resources

A New Building at NRLF

Melvyl Moves to a New Platform

Library Exhibits

New Journals

Workshops, Instruction & Library Tours

Library Research Guides

bCourses

Keeping Informed of New books

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)