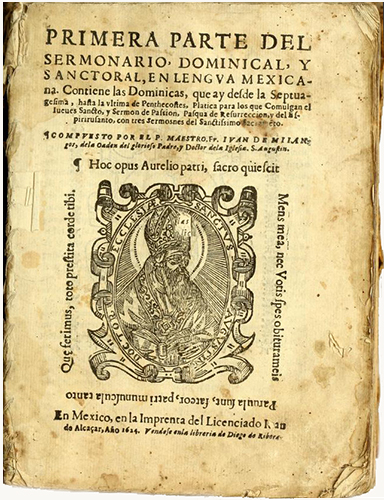

Written in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, the Primera parte del sermonario, dominical, y sanctoral, en lengua mexicana was published in Mexico City in 1624 at Juan de Alcázar’s printing press. The title of this collection of sermons is representative of the early colonial printing in Mexico City as well as the Augustinian order’s testament to the proselytizing efforts of the Catholic Church in Mexico. Only the first part of this Nahuatl text was ever published. Its author, Fr. Juan de Mijangos, is also well known for his Espejo Divino (1607).

As noted by Hortensia Calvo, director of the Latin American Library at Tulane University, Spain’s ideological, political and administrative control was possible with the early colonial press: “The first presses were brought to Mexico City and Lima for the explicit purpose of aiding missionaries in the Christianization of the native population.”[1] However, in the 17th century, following the Conquest, the Spanish occupiers dealt with many different populations of the region, hence many books were printed in the indigenous languages and, most importantly, not all texts were created for colonial or religious purposes. James Lockhart shows that, as early as 1545, the Nahuas of central Mexico adopted the Latin alphabet for their own purposes, beyond the interests of the colonial authorities and missionaries.[2] Indeed, former Berkeley professor José Rabasa argues that the “Alphabetical writing does not belong to rulers; it also circulates in the mode of a savage literacy. Bearing no trace of Spanish intervention in its production, the Historia de Tlatelolco exemplifies a form of grassroots literacy in which indigenous writers operated outside the circuits controlled by missionaries, encomenderos, Indian judges and governors, or lay officers of the crown.”[3] Several such texts have been digitized by the French National Library, including the Diario de Don Domingo de San Anton Muñón Chimalpáhin Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin (1579-1660).

Nevertheless, Marina Garone Gravier notes “there was a lack of in-depth knowledge of Nahuatl by some who composed these early sermons related books.”[4] Since the foundation of the Aztec Empire in 1325, Nahuatl played an essential role in daily workings. Published 103 years after the fall of the Aztec in 1521, the sermon book featured here evinces the continuation of Nahuatl during the early days of the Spanish Empire. Frances Kartunnen points out: “At the time of Spanish Conquest of Mexico [Nahuatl] was the dominant language of Mesoamerica, and Spanish friars immediately set about learning it. Some of them made heroic efforts to preach in Nahuatl and to hear confession in the language. To aid in these endeavors, they devised an orthography based on Spanish conventions and composed Nahuatl language breviaries, confessional guides, and collection of sermons, which were among the first books printed in the New World. Nahuatl speakers were taught to read and write their language, and under Friars’ direction the surviving guardians of an oral tradition set down in writing particulars of their shattered culture in the Florentine Codex and other ethnographic collections of Fray Bernardino de Sahagún and his contemporaries.”[5]

Today there are over one million Nahuatl speakers in Mexico and in the diasporic communities in the United States.[6] Yet, there are several dozens of Nahuatl dialects and, since this non-Romance language adopted the Latin Alphabet, it is difficult to apply standard orthographic principles to all of them.[7] Nonetheless, the following are essential textbooks for the teaching and learning of standardized Nahuatl: Richard Andrew’s Introduction to Classical Nahuatl, James Lockhart’s Nahuatl as Written, Michel Launey’s An Introduction to Classical Nahuatl and, for more advanced students, James Lockhart’s edition of Horacio Carochi’s Grammar of the Mexican Language.[8] Many other resources are available in print and digital format; for example, the University of Oregon’s online Nahuatl Dictionary, Molina’s bilingual dictionary Vocabulario en lengua castellana y mexicana (1571), UNAM’s online Gran Diccionario Náhuatl, and the app Vamos a aprender náhuatl.

Nahuatl language courses are available through UCLA’s distance learning program[9] and University of Utah’s Intensive Nahuatl Language and Culture Summer Program in Salt Lake City. The latter program, previously sponsored at Yale, has prepared many contemporary US-based Nahuatl scholars.[10] At UC Berkeley, the Joseph A. Myers Center for Research on Native American Issues has offered annual Nahuatl workshops,[11] and The Bancroft Library holds over 460 items, including the Primera parte del sermonario, dominical, y sanctoral, en lengua mexicana, concerning the Nahuatl language in its renowned Latin Americana Collection.[12]

The librarian for the Caribbean and Latin American Studies has requested this post to be published on September 16, 2019, which is is celebrated as the day of Independence in Mexico.

Contribution by Lilahdar Pendse

Librarian for Latin American Studies, Doe Library

Carlos Macías Prieto

PhD student, Department of Spanish & Portuguese

Sources consulted:

- Calvo, Hortensia. “The Politics of Print: The Historiography of the Book in Early Spanish America.” Book History, vol. 6, 2003, pp. 277–305. JSTOR.

- Lockhart, James. The Nahuas After the Conquest: A Social and Cultural History of the Indians of Central Mexico, Sixteenth Through Eighteenth Centuries. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996.

- Rabasa, José. Writing Violence on the Northern Frontier: The Historiography of Sixteenth-Century New Mexico and the Legacy of Conquest. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2000.

- Gravier, Marina Garone. “La tipografía y las lenguas indígenas: estrategias editoriales en la Nueva España.” La Bibliofilía, vol. 113, no. 3, 2011, pp. 355–374. JSTOR.

- Karttunen, Frances. An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl. Norman: Univ. of Oklahoma Press, 1992.

- Janick, Jules, and Arthur O. Tucker. Unraveling the Voynich Codex. Cham Springer , 2018.

- Andrews, J R. Introduction to Classical Nahuatl. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2003.

- Introduction to Nahuatl, Center for Latin American Studies, Stanford (accessed 9/12/19)

- Distance Learning Language Classes, UCLA (accessed 9/12/19)

- Beginners and Advanced Nahuatl Language and Culture Workshops, UCB (accessed 9/12/19)

- Utah Nahuatl Language and Culture Program (accessed 6/18/19)

- Latin Americana: Mexico and Central America, The Bancroft Library, UCB (accessed 9/12/19)

~~~~~~~~~~

Title: Primera parte del sermonario, dominical, y sanctoral, en lengua mexicana : contiene las Dominicas, que ay desde la Septuagesima, hasta la vltima de Penthecostes, platica para los que comulgan el iueues sancto, y Sermon de Passion, pasqua de Resurreccion, y del Espiritusanto, con tres sermosnes [sic] del sanctissimo sacrame[n]to / compuesto por el P. maestro Fr. Iuan de Miiangos, de la Oaden [sic] del glorioso Padre, y Doctor dela Iglesia. S. Augustin. (1624).

Author: Mijangos, Juan de, d. ca. 1625

Imprint: En Mexico : En la imprenta del licenciado Iuan de Alcaçar : Vendese en la libreria de Diego de Ribera : año 1624.

Edition: 1st

Language: Nahuatl

Language Family: Uto-Aztecan

Source: The Internet Archive (John Carter Brown Library)

URL: https://archive.org/details/primerapartedels00mija

Other Nahuatl texts online:

- Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin (1579-1660). Diario de Don Domingo de San Anton Muñón Chimalpáhin, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- Fray Bernardino de Sahagún (1499–1590). Historia general de las cosas de nueva España (The Florentine Codex). World Digital Library (Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana).

- Gran Diccionario Náhuatl [online]. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México [Ciudad Universitaria, México D.F.]: 2012.

- Molina, Alonso de, d. 1585. Vocabulario en lengua Castellana y Mexicana. En Mexico : en casa de Antonio de Spinosa, 1571.

- Online Nahuatl Dictionary (University of Oregon)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- The Bancroft Library has in its collection one of eight surviving copies of Primera parte del sermonario, dominical, y sanctoral, en lengua mexicana (1624) held in U.S. libraries.

The Languages of Berkeley is a dynamic online sequential exhibition celebrating the diversity of languages that have advanced research, teaching and learning at the University of California, Berkeley. It is made possible with support from the UC Berkeley Library and is co-sponsored by the Berkeley Language Center (BLC).

Follow The Languages of Berkeley!

Subscribe by email

Contact/Feedback

ucblib.link/languages

![The Languages of Berkeley [fan]](https://update.lib.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/fan_languages-450px.jpg)